Pine Mountain Settlement School

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH

SNOW

SNOW

In the early winter years of Pine Mountain Settlement School snow was a frequent and seasonal visitor. Snow still visits the School, though not so frequently and it rarely sticks around for long. The climate of the planet is shifting and it is getting warmer worldwide. Snow, if it falls, can now fall at alarming rates — as can rain. These unexpected, rapid and sometimes overwhelming amounts, are becoming more frequent. Sometimes snow fails to stay on the ground for a long stretch of time. Sometimes it is a soft and gentle visitor, and sometimes it is wind-driven and icy. Today, there seems to be little to no sensible planning for how snow will present itself. “Let it snow, let it snow, let it snow.”

Sometimes snow falls as rain. It is difficult to imagine there could be a cloud burst such as the one that recently dumped record amounts of water on Eastern Kentucky. The rapid and deep torrents of Troublesome Creek that quickly rose to inundate Hindman Settlement School and the surrounding valleys, and the fierce and unprecedented rapid rise of the river that rushed through the town of Whitesburg, Kentucky, were unprecedented recent events. Christmas in Buffalo, New York this December 2022, has shown us what damage massive amounts of snow can do to a city. The climate is changing.

What would the raging water of July 2022 have looked like had it fallen as snow? Is it even possible? The recent December snow in Buffalo, NY suggests it is certainly possible — perhaps not in July, but possible, nonetheless. Snow and ice in the coldest regions of the globe, such as Antarctica, are rapidly melting away. Iceland’s glaciers are pouring into the sea. Kilimanjaro, K-2, and Everest, no longer have their deep winter snow caps. The world is warming and temperatures are going up.

The climate is changing and with the change comes a growing human uncertainty regarding our relationship with snow and water — and many believe — with each other. The United States Environmental Protection Agency reminds us

Climate change can dramatically alter the Earth’s snow- and ice-covered areas because snow and ice can easily change between solid and liquid states in response to relatively minor changes in temperature.

Further, the EPA tells us that

Between 1972 and 2020, the average portion of North America covered by snow decreased at a rate of about 1,870 square miles per year, based on weekly measurements taken throughout the year. Recently, there has been much year-to-year variability. For example the length of time when snow covers the ground has become shorter by nearly two weeks since 1972, on average.

The EPA describes a warming planet where

Across all sites, snowpack declined by an average of 23 percent during this [recent] time period. Peak snowpack is happening earlier in the season at the majority of sites, as higher temperatures cause snow to melt sooner. Snowpack season length decreased at about 86 percent of sites analyzed, decreasing by an average of more than 18 days.

The message in these indicators is that the climate is warming and there are environmental consequences and causes

As the Earth’s climate warms overall (see the U.S. and Global Temperature indicator), the number of frozen days has decreased in most parts of the United States. Continued reduction in frozen days could lead to a variety of effects on ecosystems, drought, wildfire risk, agriculture, natural resources, and the economy.

The progress of global warming is erratic but scientists are clear that the speed of global warming is accelerating. Snowfall is no longer a predictable winter visitor as it was 100 years ago.

100+ YEARS AGO AT PINE MOUNTAIN SETTLEMENT SCHOOL

We did not wait for a schoolhouse to begin teaching; the House in the Woods took care of the children till snowfall until 1918, when they were distributed in the living room of various cottages; or the first three years at the Masonic Lodge over Mr. Nolan’s store.

From the biography of Elhannon Murphy Nolan

The House in the Woods was an open-air classroom built of log posts with a roof cover and no walls — essentially a pavilion. It was located on the south slope above the valley, just up from where the School’s Barn is located today. The pavilion served as a community meeting place, as well as a classroom. Like snow, it slowly melted into the earth and by the late 1930s it was unusable and was fully taken down. It is hard to imagine such an open-air classroom in today’s world of air-conditioning, digital heating sensors, and comfort engineering that monitors our interior dwellings and their relationship to the environment.

1916 Winter

By 1916, enclosed classrooms were available and the attention of the Pine Mountain workers was focused outward on the community at large. In the winter of 1916, Evelyn Wells and another co-worker, Helen Strong, walked three miles in the snow down Greasy to Joanna Turner’s, “where we collected her horse.” Snow was a familiar part of the ecosystem of the region and the change in the seasons became for the workers a part of both the joy and challenge of living in Appalachia. (See EVELYN K. WELLS 1916 Excerpts from Letters Home

Evelyn K. Wells, a native of Montclair, NJ, and Co-director of Pine Mountain in its early years, was no stranger to snow. She often wrote in her letters home of the snow in the Pine Mountain valley. But, it was with new eyes that she begins to write home about the snow in the Pine Mountain valley. Clearly, she seems to have developed a new relationship with snow. She recaptures snow as an exotic visitor, and as a beautiful blanket covering a place of primitive conditions but of exquisite beauty. Her literary picture of her early years at the School, now in its third year of evolution, is of a Shangri-la “hidden” in a white snow-filled valley. where the visitors take a “lovely” trip in the snow and find the warmth of paradise. The enchantment of Wells is not quite James Hilton’s 1933 Lost Horizon, but it is an exotic projection on a region that yearned for discovery and re-invention.

Today, nature’s earlier gifts continue to be mythologized and pursued in the remote Pine Mountain valley. While we will never again see winter through the lens of the early twentieth century, we continue to push the “beautiful” rural scenes and wrap ourselves in nostalgia. We long for lost horizons, but we are slowly forgetting what those horizons might look like . We share our longings for a Shangrila, while forgetting that the snow of Hilton’s novel was not within Shangrila, but was a cold wasteland surrounding the paradise. We join millions searching for those quiet and deep snow-falls that wrap us in beauty, but fail to remember the treachery of cold snow. We sit within our warm buildings and look out at peaceful snow falling while watching events unfold in Ukraine and Buffalo, New York. Our horizons are no longer clear and our ability to negotiate them, less certain.

Evelyn Wells writes

Helen Strong [Teacher 1916-18] and I had a lovely trip recently. We started Saturday morning, in the snow, the weather having changed in the night, walking by turns the first three miles down Greasy to Joanna Turner’s, where we collected her horse. I rode Bobby, Miss [Ethel] de Long‘s horse, and I thoroughly enjoyed it all the way, for he paced and was full of spirits. Joanna told us not to let any horses get ahead of hers, as it made him mad, and Joanna’s maw told us not to let any horses get behind him, as that made him mad! However, he turned out to be a lovely horse, full of spirits and not “mean.”

Greasy grows wilder as you work down towards the Middle Fork of the Kentucky River, and the houses are miles apart. We had dinner by the side of the creek, building a fire to cook bacon and heat a can of soup. Such lovely hillsides, covered with beech forest on one side and laurel growth on the other. There are flat bottom-lands further down Greasy, which in a thickly settled country would not have escaped the inevitable corn crop, but here they were quite unspoiled. We got to Henry Chappell‘s, where we were to stay over night, about four, and the sun had been down for an hour and a half. Henry Chappell is an old man who is rather progressive, and he has a fine farm, and a nice house. His wife is a lovely gentle woman, full of humor, and so hospitable to us. Their children, except one son, are married and have moved away from the mountains, and one of them edits a paper in Middlesboro. We saw Mrs. Chappell‘s quilts and woven covers, and for the first time I acquired an interest in quilts. She had one which was beautiful – a design of red palm leaves on a white background which had a Scandinavian effect. The kitchen was a big room with a fireplace big enough for five-foot logs, and a very modern range beside it. At the other end was a well, with good water, served from a gourd dipper.

When we sat down to supper three men came in, cattle men from New Mexico. It is a stopping place for all kinds of people. we slept in rather a dressy room, with straw matting and wallpaper, but it was the only exception I have seen to the mountain rule that every room has a fireplace. It certainly was cold that night!

As we sat round the fire after supper, they were very anxious to know all about us. They told me all about the Wellses over on Cutshin — how I needn’t be ashamed of ‘ary one of them, and they found many points of resemblance in my folks to the general Wells cast of features.

Another beautiful ride, starting at 8:30 on Sunday, coming up the frost-bound river, where we had to break the ice several times. Such stunning gorges, and big rocks in the stream, and some snow on the holly and evergreen trees and Main [mountain] Laurel, is exceptionally beautiful. One little house, very small, was two stories high and painted white with green trimmings, and had an upstairs balcony fairly hanging over the creek. The little clearing was practically surrounded by a holly grove, such staunch, stylish little trees.

We stopped for a call on 109-year-old Uncle John Shell, whom we found splitting kindling. He was most entertaining, telling us all about the game one used to be able to catch, and conditions when the country was really wild. [See:Uncle John Shell to read the real story of this “oldest man in the world]

1917 – 1927

From the transcriptions of other early worker letters gathered by Evelyn K. Wells when she served as Secretary at Pine Mountain Settlement in the 1930s, comes a chilly account of how the mail traveled to the remote School. The letter describes how mail was delivered in the wintertime by rail to a station on the South side of the tall Pine Mountain and then packed by horse across a snowy mountain. The mail came daily from the rail line and up and over Pine Mountain in the beautiful but challenging wintertime. All visitors would have to make the journey by foot unless a horse or a mule could be sent to fetch them. Until the road, called Laden Trail, was completed in the mid-1930s, crossing Pine Mountain in winter was an adventure.

Twenty sacks of mail today. They took five horses to fetch it — what a picture, crossing the snowy mountain! EVELYN K. WELLS 1916 Excerpts from Letters Home 1917 Winter. [034-p.1]

Winter and snow also brought many children and staff under one roof for long periods of time. Colds and allergies ran rampant and so did the full cycle of childhood diseases. Secretary Wells records this outbreak of Chicken-pox at Far House, the girl’s dormitory, during one early snowy winter.

Chicken-pox. Six cases at Far House, including my little roommate, who broke out tonight.

Rail fence in the snow at Pine Mountain Settlement School.

1922 WEATHER AND WELL WATER

In January of 1922 Marguerite Butler a worker at Pine Mountain Settlement School experienced a particularly harsh winter in the shadow of Pine Mountain as she assisted in the establishment of a satellite settlement at Line Fork in nearby Letcher County. She wrote to her mother about her experiences coping with the weather and her responsibility for developing the new medical and educational satellite, approximately eight miles from the main Pine Mountain Settlement School. The following describes the preparation of a well for the new facility.

Dear Mother —

Yesterday it was 10 degrees above zero, today it must be up to 60 degrees above. Such a change overnight. I had sixteen at Sunday School. They were so excited over the [photographs] pictures of play. I let each family pick the one they would like a print of.

Yesterday I had to go to Line Fork and I tell you I wore all the clothes I had. It was bitter cold and a high wind but I didn’t get cold a bit. It was beautiful with everything white with snow. The sun made it so brilliant I could hardly see. I have to go over to Line Fork again to-morrow for several days to fix the well. When I was home it just stopped running. I am afraid a joint has cracked letting in air. It will be a job to fix.

Marguerite Butler

Line Fork Settlement, an 8-mile hike or an equally slow horseback ride up over a small mountain and into the adjoining Letcher County, was a challenge in any weather. Marguerite Butler, a graduate of Vassar and an eager young and talented woman, was assigned by Director Katherine Pettit to take charge of developing the new satellite settlement and she made the journey frequently in the snow.

One of her first tasks at Linefork was overseeing the construction of a well for the settlement and for preparing a small cabin for the staff at the new facility. A doctor and a nurse would soon join Butler at the facility where she was preparing to serve as the Industrial Training teacher. By offering community classes and medical support for the remote location, Pine Mountain hoped to duplicate its model services and create five more sites in the region. Marguerite had a daunting mandate, but one she engaged with enthusiasm.

Remarkably, the job of supervising the digging of the well at Line Fork was one of Marguerite’s first assigned duties in the development of the new settlement. It was a complicated task, but a critical one as the facility could not function without clean and nearby water. She was not charged with the actual digging of the well, but Marguerite’s letters indicate she gave that task a go in the company of ready workers from the community. It was a difficult task. It would have been daunting in any season, but in winter, it was unimaginable to many of Pine Mountain’s hardiest workers. Apparently, Katherine Pettit could imagine the young Marguerite suffering a bit as she nudged the hardy Marguerite onward.

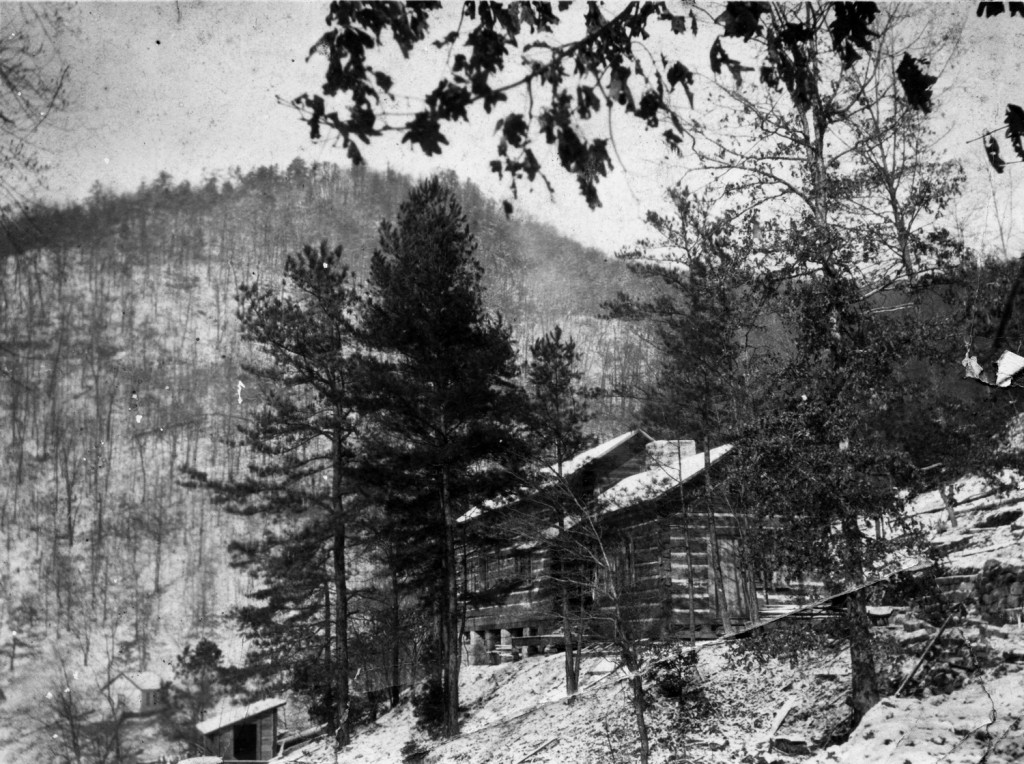

Lutrella Baker Album. The Cabin at Line Fork, in snow, distant view. line_fork_003b.jpg

On January 23 Marguerite tells us about the broken well and the working conditions

Sunday, January 23, 1922

Dear Mother —

… Last Monday morning I started out early for Line Fork to fix the water. For two days we worked and at 4 Tuesday once more had running water. The settling of the ground at the well had bent the pipe so it broke right in half under the elbow. Henry Creech came Tuesday to help us cut and thread the pipes. When we found the trouble I had to send him back to the school for a new elbow (pipe). He left on Queen [the PMSS horse} at 10:30, getting back at 1:05 – said he never was on such a good horse before. He told me to tell Jeannette if she picked a husband with as much judgment as a [the ] horse she’d get a good one.

ALL THE COMFORTS OF HOME AND CROSSING THE PINE MOUNTAIN IN SNOW

When Harriet Crutchfield came to Pine Mountain as a worker in the early 1920s, she left her home where there was every advantage. Her father, James S. Crutchfield, a School Trustee, was President of the American Fruit Grower’s Association and she was used to the many comforts that financial security brings. She was not prepared for the rugged life at Pine Mountain, especially winter and she sent a steady stream of letters to her home asking for small comforts and for items of clothing that would get her through the “Grip of Winter“. She seems to try to accommodate the environment when she finally bravely says in one letter, “This can wait for a long time …” Her want list, in one memorable letter, however, starts with “alligator shoes & rubbers” …

4. Alligator shoes & rubbers to fit. All the shoes I have down here are the kind that you can’t get rubbers over and I understand that in December it gets pretty sloppy — more rain than snow in winter here. You will have to get my alligators sewed up in the places where they’ve broken apart and have taps put on the heels. I believe there are some rubbers in the house that would fit them, but I have no idea where. This can wait for a long time.

crutchfield_journal_032.jpg page 4 Harriet Crutchfield, Correspondence 1921 Undated – n.d.

Crossing the mountain at 5:30 a.m., joining Lucretia Garfield and K. [Kay] Wright on the early train from Lynch, where they had been Girl-Scouting all week. At Harlan took another train, rode six miles and connected with what had been described as a “motor car,” which turned out to be a little truck that ran by gasoline engine on the railroad tracks six miles further, to the Head of Lick Branch, a coal mining district, We rode lickety-split, hanging on to each other, to the end of the road, where we bumped into the mountain. We were met by two little boys who took us over the low ridges to the Smith valley, only three miles, and such lovely country, winding instead of straight like ours.

We were to visit the Community Life School, a Presbyterian center (in Harlan County). Palatial houses where the people have black walnut sets and pianos and the ladies come to Ladies’ Aid meetings in plumed hats. At the creeks and hollows nearby are full of cabin homes and their neighborhood problems are much like ours. The buildings of the school are very plain little cottages, neat and comfortable and perfectly unimaginative, but there are fine workers. At a funeralizing, we saw the neighborhood gathered. The Presbyterian minister from Harlan came to officiate, and we returned with him, starting out on foot, changing to the hand-car for six miles, walking another three because the train wasn’t due for a long time, and being picked up by a very luxurious automobile parishioner of Mr. Michel for the last few miles to town.

After a night in the only hotel in town we came across Pine Mountain in a light snow, joined by a lot of children returning from vacations. Also, two little boys who ran away a month ago whom Lucretia and Kay had found in the poorhouse on their travels and who were now being returned to us by the County Judge.

THE DARKER SIDE OF SNOW

Medical Settlement – Big Laurel, late 1920s

During the 1920s snow showed a darker side. To some of those who supported the School and sought to alleviate the poverty they saw or perceived to be in the region, snow offered a means to reach into the conscience of the rich. To many wealthy supporters of the School, the pervasive and severe living conditions in the remote areas of the Central Appalachian mountains was made even grimmer by the imagining of cold snow. The exposure to snow and to the cold compounded by poverty was and is considered an inhumane event but a solid fund-raiser. The realities of the 1920s can uneasily be recalled when we read of winter miseries such as the current events of the 2022-23 winter in Ukraine.

Snow adds to the misery of poverty in the minds of many — an observation not without cause. At Pine Mountain Settlement in the 1920s the combination of snow and poverty was a means of reaching donors and friends of the School. Winter was also an opportunity to plead for programs and for workers to “uplift” the people of the Central and Southern Appalachians from their perceived treacherous environment. By providing money and educational resources the edge of Winter could be softened for mountain children. A school like Pine Mountain could shelter the mountain children from their harsh habitat and move the mountain dwellers out of the “misery of poverty” that was made so obvious while in the grip of winter snow. It was a cynical but effective means to capture the sympathy of donors.

Blanche Rannells, a visitor to Pine Mountain and a leader in the “uplift” movement, wrote a short article, “Our Mountain Neighbors,” that describes the austere environment of winter in Appalachia. From her brief first-hand encounter with winter and her efforts as a staff worker at the second satellite settlement, the Medical Settlement at Big Laurel, Blanche Rannells pulls on the heartstrings in one of her 1924 letters to prospective donors

Those of you who are interested in welfare work for children may be shocked by the statement that ” … last Sept. 30 children who entered this school together were nearly 450m pounds underweight. In two weeks regular rest and wholesome food had produced a gain for the group of 147 pounds!” If you could see the homes these children come from and know the character of their food, you would no longer wonder at the statistics reported by the school nurse.

Let me try to picture to you one of these homes. Imagine if you can the utter solitude and loneliness of a life spent in a windowless log cabin “at the head of a hollow” with none but the sounds of nature to break the sepulchral stillness. No traveler ever chances to pass the door for the winding footpath which leads to it does not extend beyond it.

Within it [the home] is even more cheerless, especially in winter, for sunlight cannot penetrate solid walls of logs. The fireplace must serve the double purpose of furnishing light and heat. A touch of color is lent to the interior of strings of “burney” red peppers and hanks of wool of various colors suspended from the rafters. Long ropes of “shuckey beans” decorate the walls waiting to be shelled when needed for food. [The writer was obviously not familiar with “shucky beans” or “leather britches” which did not require shelling to be eaten —as most times, the beans were cooked with shell and bean.]

WINTER WITH THE STAPLETONS AT LINEFORK 1922-1942

Some of the most detailed early records of snow and cold came from the extension centers of Line Fork and the Medical Center at Big Laurel. The Stapletons who supervised the Line Fork facility in the late 1930’s and early 1940s, described many winters at the remote Line Fork Cabin. They also captured the lives of their neighbors around the clinic and the isolation of those families. But, they also capture the beauty of winter shared by many who lived in the Line Fork community.

Lutrella Baker Album. The Cabin at Line Fork, in snow, distant view. line_fork_003b.jpg

Lutrella Baker Album. The Cabin at Line Fork, in snow, distant view. line_fork_003b.jpg

In 1927 Dr. Ida Stapleton and her husband the Rev. Stapelton arrived at Linefork. They describe the first four months and their first winter

Before night the rain began again and continued thru our own Christmas Day which we spent in the Cabin. It was the first one spent alone by the Stapletons for many years. The schools had but one day for vacation and so on Monday the lessons began again and singing was taken up with the idea for closing exercises in February. New Year’s Day was a winterly one and a regular blizzard was the weather program. Thru out the day only one caller came to the Cabin and he was our neighbor who brought us the milk.

Stapleton Correspondence 1925-1927

The Stapletons had many winters (1925-1944) at the Line Fork Cabin and their informative reports and letters detail the extremes in weather they experienced while living there. See Stapleton Correspondence Guide

1933 REPORT – December “Dear Friends: — At the peak of the Year — and we are having our first snow storm which did not last but half an hour. The Fall has been about as perfect as we could wish. Just cold enough so that a moderate fire is sufficient…” [6 pages]

At Christmas, we found all the country covered with a thick white blanket of snow. The evergreens were so lovely it seemed quite unnecessary to have any further decorations – but in the schoolrooms it was quite different and the trees were trimmed in the usual way with candles, tinsel, holly wreaths and bells….

It has been too cold and frozen to do any more digging [of coal] so Johnny is splitting palings to fence in some land of his own. He has about five acres and has recently sold a half acre to a younger brother for fifty dollars on which to build a house for his newly acquired wife and in order to pay for it he tried unsuccessfully to beg a load [of coal] from the Cabin.

The next day I went up Jake’s creek to see Orrie who had been to the Cabin a week before for medicine. Now I called to see how she was getting on. She had been much better for a few days. Then she had to go foraging for coal while her father-in-law stayed in the house and nussed the baby. Why hadn’t he gone? The neighbors laughing say “That Dick would sit and freeze to death before he would pack coal”. Not quite as bad as that I reckon but at this time he wouldn’t, so Orrie rode the mule a mile to the coal bank where a quantity of coal had been taken out and after filling two pokes with it she loaded them on to the mule and walked back. She had another heart spell and was in a faint for some hours. I had warned Dick that she must not get wood for a month or two but he wouldn’t [warn her], and her brother, a young man, wouldn’t, so she had made the effort to keep her babes from freezing. Some families are helpful to their relatives, then again they are quite heartless.

[STAPLETON REPORT 1930 – January.]

A DEMORALIZING SNOW?

Another ambiguous response to snow is found in the correspondence of Katherine Pettit writing to a former staff member, Lucretia Garfield in January of 1927. She speaks to the beauty of the snow and wishes that Lucretia could see the snow at the Pine Mountain School

I wish you could see Pine Mountain today, with a new, fresh fall of snow. It’s so beautiful it’s a demoralizing and makes everybody want to stay outdoors and not work at all. But this is the first day of the new term and so we all have to plunge in to it again after our good vacation.

ALICE COBB STORIES 1930s-40s

Alice Cobb, another worker at the School, gathered many stories of families in the community as they struggled with harsh winters and the cold and drafty cabins in which many of them lived. Cobb remembers with some poignancy, one conversation on her “Farewell Trip” to visit community friends as she prepared to leave Pine Mountain after many years of service

“I wish I could remember all the stories — perhaps I will from time to time and can jot them down. I tried so hard to memorize them as he [Abner] went along but you just can’t remember all Abner’s nice little sayings, and fancy words. One thing I remember, when he spoke about a cold winter, with the snow and tree branches a poppin’ and a crackin’. And then he asked me about you [Cobb’s Mother, her correspondent] and…

Alice Cobb’s Farewell to Line Fork,

…how many children there were at home. I said you [her Mother] had to be there alone most of the year. He was quite severe — asked how often I went home. I said only once or twice a year. He shook his head and said “And you don’t stay home no more than that — and them without ary chick nor child?” You see his idea is that a family should stay together, and he doesn’t want his children to come even as far as Pine Mountain school. He feels that their family circle must be unbroken — it’s a beautiful affection they all have for each other, and while in any other family I wouldn’t like it, in his it is different.”

June 14, 1937

(Via Little Laurel, Big Laurel and Turkey Fork)

1944

Lela Christian, Nan Milan, Stella Taylor, Nancy Jude. Student Community Service Workers, c. late 1930s – early 1940s. [duplicates_069.jpg]

The academic programs in the late 1930s and the 1940s pushed the older students out into the Community where they would experience the life of the people and provide much-needed social service supports as Community Service Workers. This program, designed by Director Glyn Morris was ground-breaking in the rural setting of Eastern Kentucky and led to expanded development in the later regional Rural Youth Guidance programs initiated by Morris. I t was also a model for the Frontier Nursing service that later was developed nearby. The students seen above were trained by Grace M. Rood, who at the end of her life wrote of her work training students in the nursing field.

‘BATTLE OF THE YEAR’ SNOWBALL FIGHT 1944

While the School program was rigorous, it also made room for students to revel in the joy of play, and snow afforded the perfect playground. In this article from the 1944 Pine Cone, some of this revelry is described. It is a description familiar to any child who has had the joy of pummeling their schoolmates, no matter their age, with snowballs.

The deep, wet, and heavy snows that were, and are, common at Pine Mountain, provide perfect playgrounds for students to engage in snow-ball fights like the one described below by student, John Deaton

BATTLE OF THE YEAR” by John Deaton – Snowball fights among students from the various dormitories.” 1944 Pine Cone

As snowball fights were to be the order of the day with Boys’ House challenging Far House and West Wind offering to battle Big Log, everyone went home and changed into warmer clothes.

The scene of the boys’ skirmish was Far House lawn, which Boys’ House captured at will. The luckiest break for Boys’ House was the charge that netted us a panful of snowballs manufactured by Far House. Neither side can be declared the victor but Far House firmly declined an invitation to continue the fight on the playground which is nearer to Boys’ House.

The girls did not turn out in large numbers, but they surely created more excitement. The bandannas which were worn to protect their hair slipped off. The result was a generous amount of mud and snow in the hair of the participants. The mud was thicker and more plentiful than the snow, and much mud was mixed with the snow balls. this fight should go to West Wind, which was greatly outnumbered but kept on the offensive almost all afternoon. We are all looking forward to another afternoon of slinging snow.

[John Deaton, January 1944, Pine Cone, pp.12-13]

1947 POST-WAR YEARS

“Daffodils and snow do not mix well. Still they are trying…”

Like the daffodils and snow, H.R.S. Benjamin, the new Director of Pine Mountain in the Post-War years was caught in an equally incongruous event. As the Pine Mountain boarding school teetered on the edge of collapse following the financial downturn following the war and the departure of former Director Glyn Morris, Benjamin faced overwhelming challenges. Buffeted by the shifting economy and by the consolidating educational framework in the early post-war years, Benjamin found himself in a blizzard of enormous challenges. But, with the promise of the beautiful and unique building West Wind nearly finished, he set about trying everything he knew to find the right mix of despair and enthusiasm.

The rapid shifts in climate only added to Benjamin’s anxiety about the many looming shifts in the educational and economic climate that would have to be addressed, and as the bills for West Wind crossed his desk, he stepped up. The sizable building project of West Wind initiated by Morris to fill the need for a girl’s dormitory, was now a huge financial burden for Benjamin. Further, as the boarding students dwindled and the post-war economy grew more fragile, the boarding school was deep in a snow drift. But, as Benjamin walked out of the Office he saw the beauty and potential of Pine Mountain ….”… the daffodils pushing their way up through the snow.”

One can perhaps imagine that he was also thinking of Mary Rockwell Hook, the School’s architect sitting in the sun of Sarasota, Florida, with her daffodils and palm trees as the snow filled his disintegrating horizon. We will never know if his remark was one of despair or hope, but it was certainly an apt description at the time. It is still a common sight at the School to see the early daffodils keep trying to bloom through late winter snow … joyful yellow in a sea of white.

In February Benjamin wrote another letter of seasonal change and longing to a former Pine Mountain worker

February 5, 1947 an

Dear Miss Sparrow,

I guess the near-zero temperatures this week are more in keeping with the season than the spring breezes which we enjoyed last week, and most of the winter, but they are scarcely as pleasant! We think often in this weather of our many Pine Mountain friends basking in Florida Sunshine.

H.R.S. Benjamin, Director

This signals that while despair was lurking, change held promise.

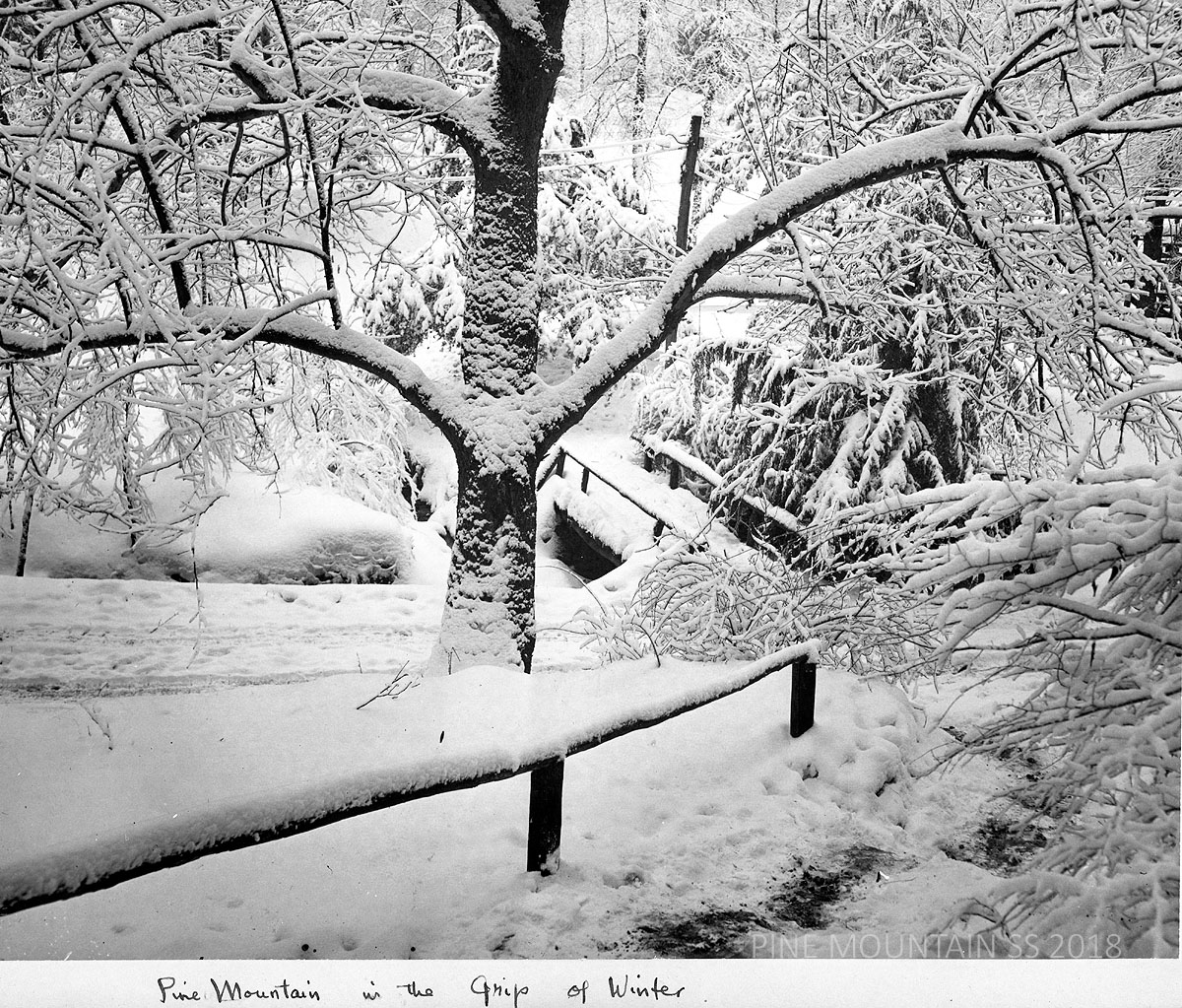

Pine Mountain in the grip of winter. [Arthur Dodd, Photographer ?] 1940s

1940 LADEN TRAIL AND THE JOE WILSON STORY

The migration of Joe Wilson and his family from Pine Mountain over Laden Trail to Harlan in the depths of winter is one of the most memorable snow stories of the School’s third decade. Alice Cobb, who accompanied the family describes the caravan that set out in the snow to cross the mountain in an overloaded truck and the adventure that ensued. Cobb captures both the social and the physical misery of the transport and of change, in this clip from her short story Migration from the Hinterland to the Industrial Area [Harlan]

When the morning came it followed a sleet storm, and we awakened to a new world, coated with ice, every little branchlet of every little tree glorified, shimmering. One was shocked by so much beauty, so lavishly displayed and I thought with embarrassment for mankind and the things he is proud of, — the glass flowers in the cases at Harvard University, tenderly buried underground in case of fire — when here was this inimitable glory, a thousand miles from anywhere at all, blooming for a day, and careless of existence.

I slipped and slid over the cinder path to the office, to see what was going to be done about the trip over the mountain. Brit [was …? …?] said certainly he would go and hadn’t he been up since four o’clock out to the Wilsons, loading their house plunder on the truck.

READ MORE …

Alice Cobb, Migration from Hinterlands to Industrial Area, c. 1940.

PHOTO GALLERY

-

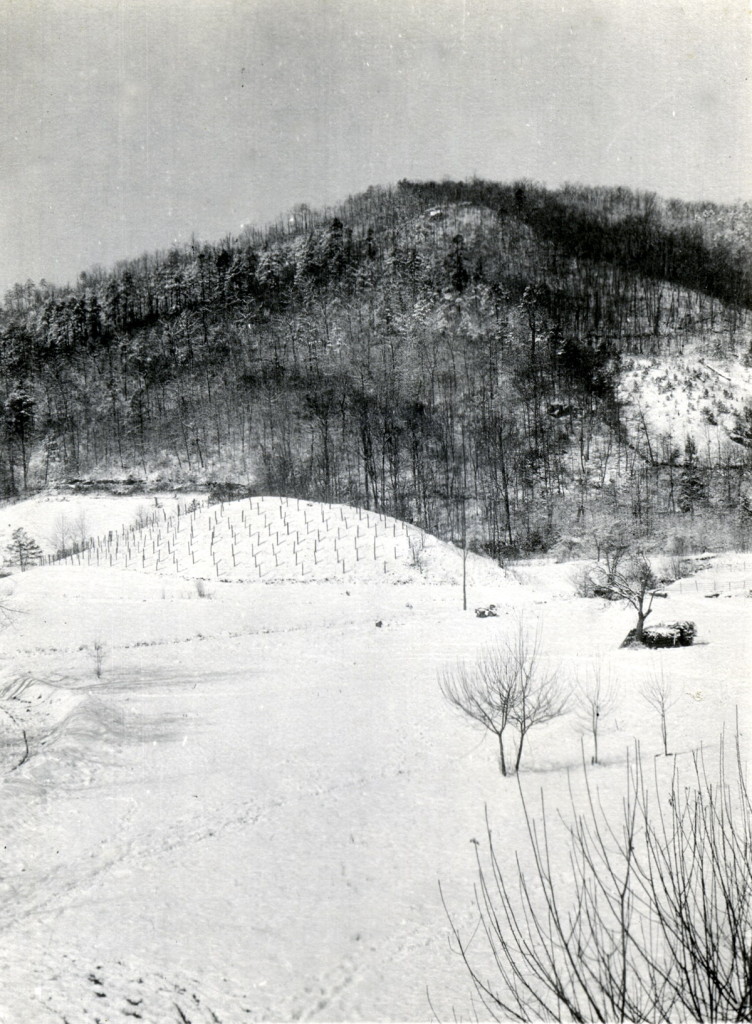

[View across campus toward Grapevine Knoll, in snow, c. 1946.] [nace_1_028b.jpg] -

Medical Settlement- Big Laurel. View of buildings in snow landscape across from Medical Settlement. [big_laurel_3338c.jpg] -

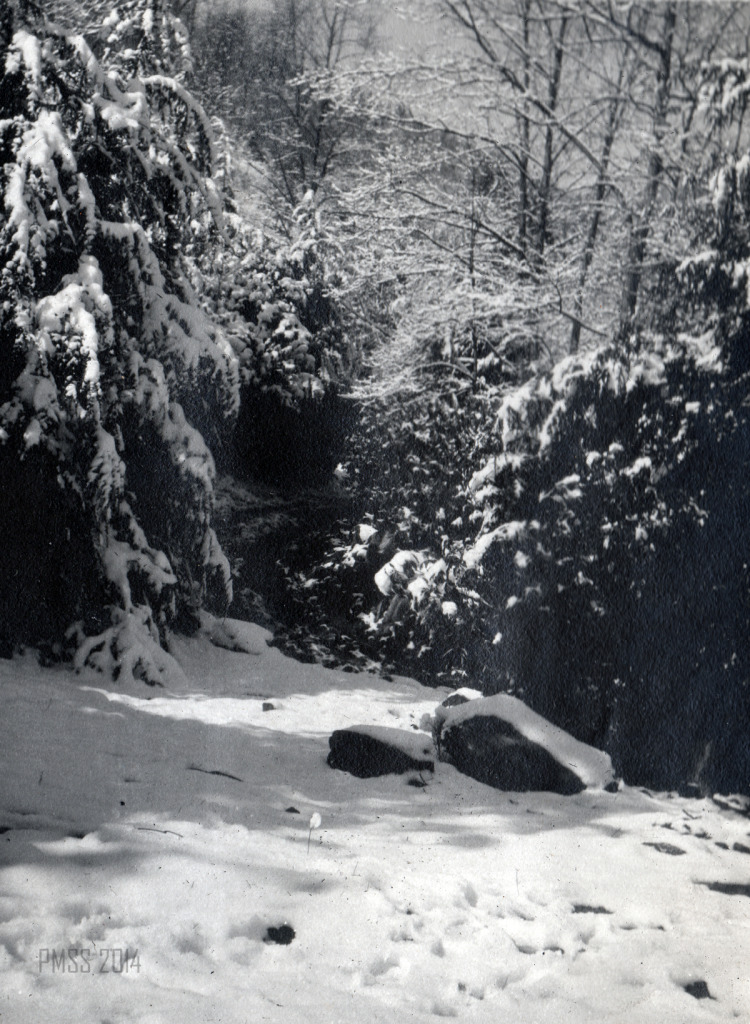

Maya Sudo Album: Snow-covered road lined with hemlocks and pines. 032a -

Maya Sudo Album: Hemlocks and stones covered by snow. 035b -

Maya Sudo Album: Snow-covered stream and foot-bridge near Old Log [?]. 033a -

Chapel and Creech Cabin in the snow, distant view, 1999. [II_11-02_creech_cabin_0402-2.jpg] -

Creech Cabin in the snow, distant view. [II_11-02_creech_cabin_0401a-2.jpg] -

Grapevine knoll in snow. II_3_general_views_147a_mod -

Office. Distant view in the snow. [II_5_old_log_office_227a.jpg] -

Girl’s Industrial. Distant view of Boy’s House behind and to right after snowfall. -

Chapel, c. 1930s. Western flank in snow, seen through trees. Photograph by Arthur Dodd. [pmss3191mod.jpg]

Far House II, Pine Mountain Settlement School, c. 2018.

SEE ALSO

Alice Cobb, Migration from Hinterlands to Industrial Area, c. 1940