Pine Mountain Settlement School

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH

Weaving at PMSS 1930s-1940s

Series: BY TOPIC – Arts & Crafts

Weaving

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH Weaving at PMSS 1930s-1940s

MARGARET MOTTER AND THE COLONIAL COVERLET GUILD

Margaret Motter was a worker at Pine Mountain Settlement School in the 1920s and 30s and again in the 1940s. She served as Principal and teacher from 1928 until 1938, and as the Publicity Representative and Head of the English Department from 1946 until 1949. She was a prolific writer and a clever and persuasive speaker. Associated with those skills, was her importance to the School as a fund-raiser. Many times she was asked to represent the Pine Mountain Settlement and to travel to distant cities to speak to special audiences that might find the programs at Pine Mountain worthy of support. Many times she managed to bring her favorite subject into the talk. In one instance she found the perfect audience for her interests and for those of Pine Mountain the Colonial Coverlet Guild of Chicago, Illinois.

Weaving had long been one of Miss Motter’s favorite crafts and she found many ways to integrate comments on the weaving program at Pine Mountain into her public speaking tours. When she shared her interests with the Colonial Coverlet Guild* in Chicago, Illinois, where she spoke on November 10, 1948, it was clear that her enthusiasm captured her audience. Miss Motter enjoyed this talk and so did her audience.

To accompany the talk to some 80 members of the Guild, she brought along many of the coverlets and weaving samples from Pine Mountain. She described the origins of the patterns, dyes, and some of the stories that came along with the individual pieces. She was able to build a picture of the community of mountain weavers. She described how for many years weaving was a household necessity for mountain families and how that skill had been adopted by the School as part of the curriculum to ensure the continuation of the craft. For many children in the community, weaving was even a new art as commercial fabrics began to dominate wardrobes by the turn of the century.

Motter emphasized how the art stayed with a number of the graduates from Pine Mountain and in some homes in the Pine Mountain valley, families established their own looms and weaving as a cottage industry to provide additional income for the family. Pine Mountain’s efforts to encourage weaving were shared by the organized cottage industry known as the Fireside Industries which broadly supported craft in the Appalachian mountains.

When Margaret Motter addressed the Colonial Coverlet Guild* she wrote out her talk in her unique abbreviated form and years later left Pine Mountain a copy of this talk and others, as well. Her talk is transcribed below. Many of the abbreviations have been expanded in this version and individuals are identified, where known. The talk is a window into weaving activity at the School and the role Miss Motter and others had in encouraging the continuation of this mountain traditional craft by integrating the craft into the Pine Mountain educational programs and offering it as a part of their Industrial Training program. Further, the focus on weaving was melded to the social outreach of the School and was used to engage the broader community and to stimulate the potential for economic independence for many women in the community. In many ways weaving and the values of the settlement movement were well paired.

TRANSCRIPTION OF MOTTER TALK

MESSAGE TO COLONIAL COVERLET GUILD

November 10th 1948

By Margaret Motter

Many of you are familiar I am sure with the institution and the dramatic beginnings of Pine Mountain Settlement School, but any sort of message about our school is incomplete without mentioning the name of William Creech, affectionately known as “Uncle William.” Here was a man with a 3rd-grade education but with great vision who dreamed for 30 years of a school that would “holp” his people.

When he gave his land (all he had) [not quite!] he wrote some men in his un-lettered hand which we treasure. I want to give you the closing paragraph to remind you of the ever-recurring challenge from Uncle William to carry on —

“I don’t look for wealth for them ….

So through the years Pine Mountain has been serving an isolated rural community as an extension, housing a secondary and a vocational high school and as a center of culture, and social and economic welfare.

Uncle William believed it was “better for folkes children to learn how to work with their hands…” In following this advice of Uncle William Pine Mountain has had from the beginning what we call a work program. Pupils pay $10.00 – $15.00 per month if they can afford it and work 2 1/2 hrs. per day and longer on Saturday. This work program serves a dual purpose. Children are made to feel the value of the education that they are earning thru work. [It] keeps [their] self-respect, values and dignity of work itself and besides, through the work program the school is kept going. The children learn over a period of years and do all kinds of work connected with homemaking, farming, and some trades or vocations. All work is done under supervision and changed every 9 weeks. Children have on [the] whole a fine attitude ….

“One thing I don’t like is learnin’ but I like what hit makes you be…….” [Comment by Brit Wilder one of the youngest students and the first to come to the school]

Now, a very popular part of our work program as well as an elective study during school hours is our weaving. I want to give you a few details about this department since you have been good enough to share in making this department function.

Our weaving room has recently been enlarged and we have space for more looms and better looms. We have by no means enough to meet the demand. We have 9 looms and one small one owned by the teacher. 6 of these were made at Berea, one at Pine Mountain after the Berea Style — 5 of the looms are 40″ and 4 are 22″-24″. Since 6 of the looms were at Pine Mountain before 1924, I guess it is not an understatement [page 3] to say they have not the latest improvements!

Our teacher informed me that a Swedish weaver told her we are doing very well indeed with the equipment we have. So you can see as time goes on we shall need to replace these older looms with better ones and to purchase a pair of badly-needed scales [?] for the weaving room.

I have brought you some samples of weaving done by our girls. We use rags from feed-sacks which are dyed at the school and woven into rugs. Old rayon stock and any kind of woven underwear can be transformed in the weaving room into lovely bags. We have a neighbor who does some spinning for us and [the] other yarns we buy.

I mentioned that our weaving is very popular. Some girls who learned to weave have been able to get a loom at home and have continued in their work. Two of the senior girls have been especially interested “in weaving and confided in the teacher that they hope they’ll get a loom as a graduation gift from their home folks. The girls love to weave a skirt to wear on May Day and have a chance to participate in the colorful “Weaver’s Dance”.

Weaving class in hand-woven skirts. Pearl Taylor, Ernestine Vitatoe, Bess Taylor, Jolene Lucas, Gladys Carroll, Reba Blevins, Margaret Slusher, Betty Huff — 1946. nace_1_022b.jpg

Weaving does go on in some of the homes (as I mentioned), i.e., sample curtain [cur. ?] material [mat.?] woven by one of our neighbors. [The] Swedish pattern sells for $1.95 a yard. I am reminded at this point of the way I happened to get one of my coverlets when I was at Pine Mountain in the fall of 1928. In the office welcoming children as they arrived — In came last years student with a younger sister by hand and [a] coverlet over [the] other arm. “I brung —–[?] “

That coverlet was definitely a home product, brown from walnut hulls and dusty rose from madder. Just as lovely today as when I bought it and I love to think that little Della [Hayes] — now a successful nurse — had her start at Pine Mountain because her sister had learned to weave at our school and had a loom at home.

[page 5] I am sure you are familiar with Dr. Allen Eaton’s book, Handmade in the Southern Mountains. [this should read, Allen H. Eaton. Handicrafts of the Southern Highlands], One of the colored illustrations shows a striped blanket that we call Pine Mountain Blanket #16. I have one of these made by a mountain woman who was taught to weave by our teacher — wool from her own sheep and vegetable dye used. This is the type of blanket we always use for our prophets in the Nativity Play. You can see that the weaving even goes into something special like that. *[Note: This same Pine Mountain Blanket #16 was used as a cover for the plaque which was un-veiled at the Pine Mountain Settlement School Centennial celebration in August 2013.]

I say something special, Christmas at Pine Mountain is an occasion that one never forgets. With our sacrificial meals for our Charity Fund now we’ll have something to share with others; with our appealing drama of lovely carols in [Laurel House] dining room while decorated with garlands, wreaths, and tree; with our gay Mummer’s Play ; with our charming Nativity Play in the Chapel, it is an occasion for happy activity — [a] genuine pleasure. It has its effect upon children “Love and joy …” —“Hit’s peacefulest –” [Motter probably describes the change from the earlier celebrations of Christmas that were known for their liquor and guns.]

![Boy's House Wassailers and Lords and Ladies -- 1946. [Good King Wenselaus ?] [In Laurel House] nace_1_025b.jpg](https://pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/nace_1_025b-1024x573.jpg)

Boy’s House Wassailers and Lords and Ladies — 1946. [Good King Wenselaus ?] [In Laurel House] nace_1_025b.jpg

Your share in our work is indeed heartwarming to the staff and the trustees. May we ask for your continued interest so that we may not fail to make Uncle William’s dream come true — I don’t want hit to be for this local. only —-” ——

*Swygert, Mrs. Luther M. Heirlooms from Old Looms A Catalogue of Coverlets Owned By the Colonial Coverlet Guild of America and Its Members – R.R. Donnelley and Sons : 1940 (1955).

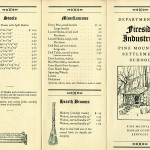

FIRESIDE INDUSTRIES

- fireside_brochure_003.jpg

- fireside_brochure_001.jpg

- fireside_brochure_002.jpg

Through Pine Mountain’s efforts and the support of the broad-ranging Fireside Industries, a strong program of support for the Appalachian craft of weaving was developed and the practice was strongly revitalized in the 1930s and 40s. In many environments, during the 1930s and 1940s the idea of a “cottage industry” which is characterized by contracted work completed at home and then marketed through a central agency, was a developed and viable economic venture. In the case of Pine Mountain, the idea was not new and was not exploited by the school so much for commercial reasons, but was incorporated into the educational program and into their primary goal of building “community.”

The idea of weaving at home was not unique to families in the Pine Mountain community but with Pine Mountain’s encouragement, it began to follow the model put forward by the Fireside Industries which flourished at centers such as Berea College, long a source of inspiration and support for the School’s weaving enterprises.

Pine Mountain’s interest was also shared by many other rural settlement schools in the region, particularly in the early settlements institutions in Western North Carolina. What was unique at Pine Mountain was the early adoption of weaving and the measure of enthusiasm in the community for such work and the persistence of weaving as part of the educational program at the school.

Weaving has been an activity that has found a place at the School for over 100 years and more of its history. Through the enthusiasm of Katherine Pettit and her “kivers” and those like Margaret Motter, who followed her, Pine Mountain has maintained it’s interest this this unique craft and in the long family traditions attached to weaving in the Central and Southern Appalachians. This long mountain family history led to the introduction of weaving and dying in the first decade of the school and maintained it through the years.

Katherine Pettit’s Dye Book written by Helen Wilmer Stone, a staff member at Pine Mountain, is a classic in the genre of vegetable dying of fiber. Under Katherine Pettit, Helen Wilmer Stone, Margaret Motter, Florence Daniels, Abbie Winch Christensen, Becky May Huff, and others, weaving and spinning, and the use of native plants for dyes later found a place in the curriculum of the Pine Mountain and other schools as a vocational tract. When a more normalized curriculum was mandated by public instructions guidelines, weaving still remained as an elective at many of these schools, and often as an after-school program. Yet, in most schools and homes, weaving had gone away by the late 1940s. Few instructors could be found to maintain the craft in schools other than arts and crafts schools and the maintenance f the equipment was high.

Unlike many regions of the Central and Southern Appalachians in the 1940s, the Pine Mountain Valley had not fully abandoned weaving in some households. In many homes in the mountains, and in the Pine Mountain region particularly, many families still maintained their old looms and many of the unique patterns continued their persistence through many generations of family weavers. Some of the old patterns can still be found in mountain homes scratched out on rolled strips of cloth or on long scrolls of paper. Like some ancient runes, these patterns are family treasures.

What Pine Mountain brought to the Fireside Industries or the “cottage industry” model, was a renewal or revival of the long-standing culture of eager mountain weavers. Margaret Motter moved this enthusiasm along by carrying examples of weaving with her on almost every talk she gave outside the School. Through Katherine Pettit’s early enthusiasm for collecting mountain “kivers” the attention to the beauty and skill of mountain weaving moved among the staff of the School like an aesthetic mantra. Workers discovered in weaving sophisticated and beautiful local craftsmanship that utilized skill, intelligence, and tenacity — qualities that the community weavers had in abundance. The education that occurred between the workers and the community was mutual — and it continues to be mutual today, even as the “community” of Pine Mountain has continued to expand outward to meet the demands of the industrial world and a more diverse public.

WEAVING IN 1949

A short piece written by Freshman student Mattie Mae Adams in the February 1949 PINE CONE, the student newsletter, describes a weaving experience at the School. 1949 was the last year the boarding school was in operation.

WEAVING

On my entrance to Pine Mountain I had a choice between science and weaving. I took weaving. At first I was afraid to weave. I was afraid I would make a mistake. It seemed hard for me to remember all of the names of the parts of the loom, and it was still harder to wind a bobbin. But it didn’t take me long as I have Miss Christensen for a teacher.

She started me off on a rug that she had already started herself. Afterward, I thought I wanted to make one for myself. Now we have started on our May Day skirts, which are very difficult, because I get my threads crossed and have to take them out. Then I have to re-wind a bobbin. The next thing I know I’m using the wrong treadles or mending a broken heddle. Broken threads are another difficulty. I have just mended a broken thread when I discover a mistake which has to be taken out. Then I usually take out two to that four.

Now all of these things don’t happen every day; but when one happens it seems as if they all happen at once. Even in spite of these hard tasks, I am glad I made the choice of weaving.

Mattie Mae Adams, Freshman

Ccropped image of weaving held in the Katherine Pettit Collection in the Bodley-Bullock House, Bodley-Bullock House. Sorority House for Transylvania College. 200 Market St, Lexington, KY 40507.

SEE ALSO: