Pine Mountain Settlement School

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH

Sheep Shearing and Cecil Sharp

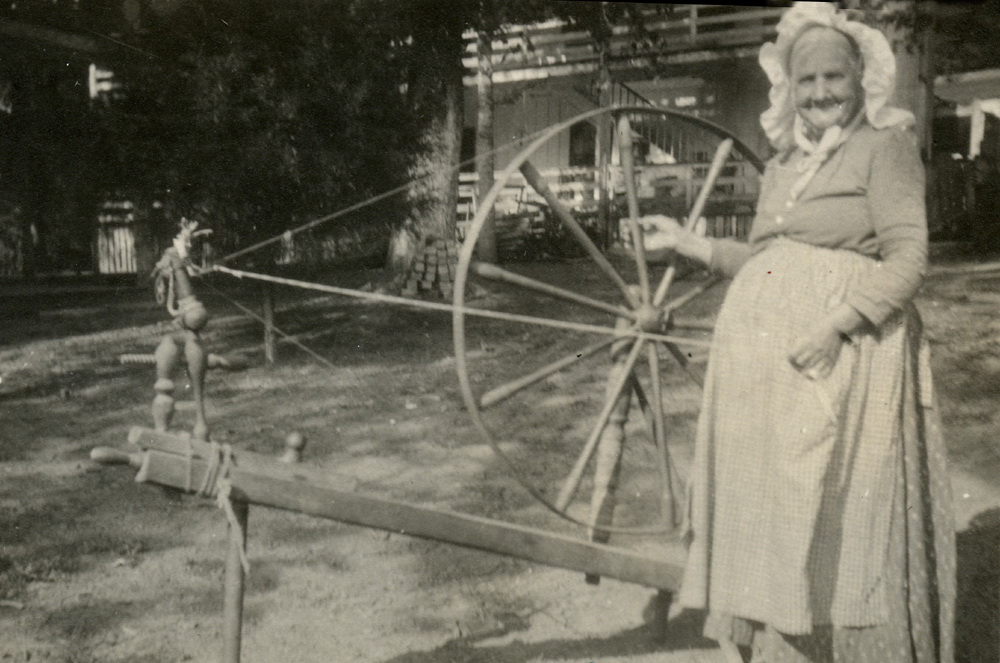

0046a P. Roettinger Album.”Sheep Shearing, Uncle John Shell, Aunt Sis Shell, and Mrs. Joe Day.” c.1920s [Woman standing next to a barn on left, watching man and woman sheer a sheep.]

SHEEP SHEARING and CECIL SHARP (Say that fast!)

It is not likely that Cecil Sharp (1859-1924), the British musicologist, ever sheared a sheep. But, he was, in any case, a close observer of the ruminants and probably an even closer critic of their bleets and baahs! Nonetheless, what Cecil Sharp has left to the history of sheep is a unique auditory trail that helps to re-trace the prevalence of sheep within the rich agrarian history of Great Britain and in the American Appalachian mountains.

When musicologist Sharp sat on the porch of Old Far House at Pine Mountain Settlement School in Kentucky and watched the Kentucky Running Set as it was performed by students and staff, he was watching the well-trained legs that probably had chased a sheep or two up the Pine Mountain and down. Tending sheep is an active job and the energy of that Kentucky Running set is just a short measure of the energy that is needed to maintain a sheep flock in the mountains of Eastern Kentucky.

SHEEP IN APPALACHIA AND BORDERLAND CULTURE

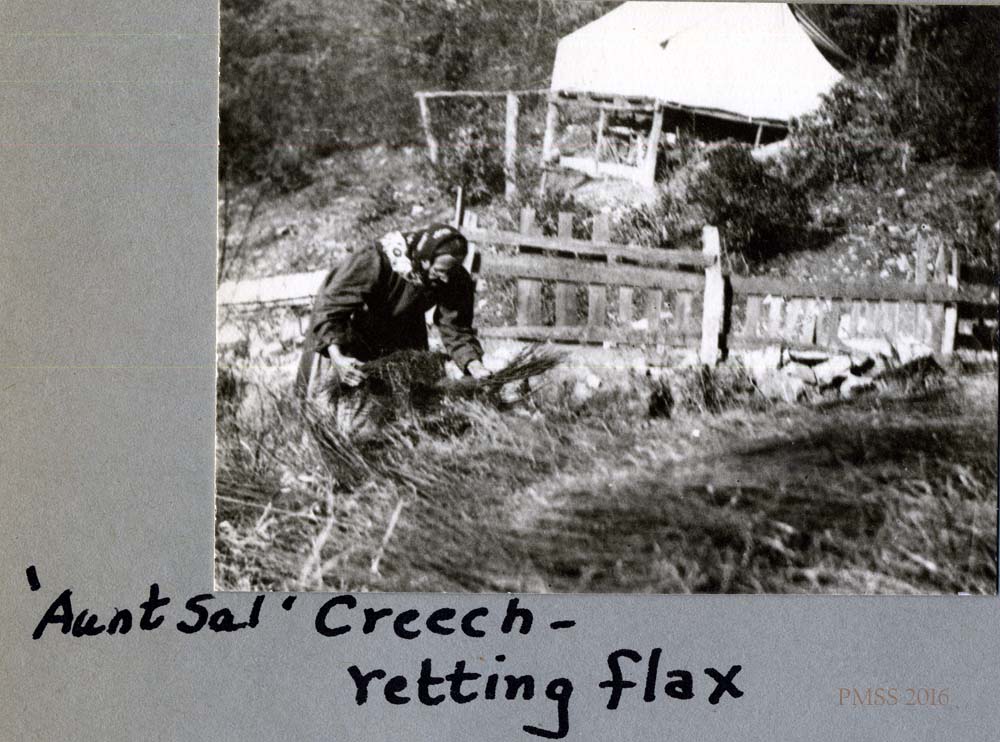

in the early years of the Central Appalachians, in the small hillside farms, it was a celebration when lambs arrived and again when wool was sheared. In the far-off “lands across the sea,” as Uncle William Creech, a founder of Pine Mountain Settlement used to say, many Europeans were continuing similar agrarian practices, particularly those people of the so-called “Borderlands,” that narrow bridge of land between Scotland and England. This region has long been associated with the early settlers of the Central Appalachians. The European Borderland customs and agrarian practices lingered on in many of the immigrant ancestors found in the Appalachians. In fact, they formed one of the largest immigrant groups living deep in the Appalachian mountains.

The raising of sheep was built into the early Appalachian pioneer imperative. Like so many of the customs familiar to the European immigrants from England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland, and also those from other points of origin with agrarian roots, sheep were fundamental to survival. As an international livelihood, sheep flocks and along with those of goats are closely tied to the stories of agrarian cultures.

CECIL SHARP, SHEEP, AND SONGS

What Cecil Sharp added to sheep history was the discovery and transcription of an English folk song that no doubt flowed from the music and lives of early sheep farmers. While his discovery was not in the Borderlands but was probably in the Norfolk area of England, it captured the centrality of sheep to everyday agrarian life.

When Cecil Sharp made his journey to America and eventually to Appalachia he wove the common elements together. Other song and ballad collectors preceded Cecil Sharp, but few had his broad recognition. When Sharp identified the British elements found in Appalachian songs and ballads he opened the flood-gates to other musicologists to marry Appalachia to “Merri Old England.”

While Sharp was interested in the music, the music held a history that was less obvious. This is the relationship of the music to agrarian practice. While the growing obsession with “Merri Old England” in early twentieth-century America assured a close historical musical bond it also revealed something of the common agrarian practices. The catchy alliteration of Sharp’s collected songs underlines the importance of sheep in the daily lives of agrarian Europeans and their ancestors in the Appalachians. Alliteration and all its musical overtones came naturally to the early oral culture of England and Appalachia. Mother Goose rhymes such as “Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers … etc. ” is well known on both sides of the Atlantic as are many other ditties. But, just try saying “Cecil Sharp and sheep-shearing,” and see what lyrical lapses leap from your tongue and fix on your memory. Songs of shearing sheep are not at all uncommon, especially in families with a weaving willfulness — a trait that springs from sheep-herders and that abounds in the mountains of the Central Appalachians and across the world. Our first school yards were the pastures of the world.

COUNTING SHEEP AND DREAMING

Even as we sleep, we are not far from the sheep pasture. It is no small wonder that when we speak of dreaming, we also often speak of “counting sheep.” There is a very practical origin for that numerical association. It was the duty of the herdsman to know the number of sheep in his herd. It was a daily practice. Counting sheep is deeply etched into the fabric of descendants of sheep-herders and deep in the historical agrarian psyche. We have been counting sheep for as long as we have joined our lives with the practice of raising sheep and other herds of animals. Sheep have been a part of our history as a country from the beginning of European settlement and have had considerable influence on our practical and formal education. At one time Kentucky led the nation in the number of sheep. For Kentuckians, that is a lot of counting and a lot of dreaming.

Yet, Cecil Sharp was a collector of songs, not sheep, nor wool though he shows all the instincts of a weaver, dreamer, and numerator. He began his collecting of folk ballads in the English countryside. There, it was inevitable that he would encounter a myriad of sheep and those who tended them. Those country sheep herders had a deep association with alliterative language and ballads and ditties. Some references to sheep were sure to appear, and they did.

The song that Sharp recorded on his journey to Norfolk was one that succinctly captures sheep and their shepherds. That ballad from his song-gathering encounters, was published in a small book he edited called 100 English Folk Songs [ published by Oliver Ditson Co., Theo. Presser Co. Distributors, Philadelphia, 1916].

SONGS FOR ALL TIME [Songs of All Time]

One of the songs in Sharp’s collection found its way into another small book of collected folk songs. The Songs for All Time printed at Pine Mountain Settlement School was issued by the Council of Southern Mountain Workers c. 1946, and was intended to be a resource for “recreation material in the Highland [Appalachian Highlands] area.” It was a utilitarian collection of songs for social gatherings that is largely dependent on the rich oral tradition of the Appalachian region and that contained many familiar tropes that would be recognized in Great Britain. The Foreword tells us that

The contents, folk songs for the most part, were compiled by a committee which has made practical use of them with singing groups. Where tunes and words depend on oral tradition, innumerable versions usually exist — some of them perhaps better than [the] variants included. There is no version which can be called the correct one, but the committee has chosen those which it has found satisfactory in the light of their lasting qualities and the ease with which they can be learned. Modal melodies are not always easy to introduce to those unfamiliar with such music, but practically all songs included have been put to the proof: given a little time and repetition they “sing well” and become dear to the heart of the singer.

Song For All Times [Songs of All Time], Copyright, 1946, by Cooperative Recreation Service, (Forward). [4 editions published in 1946 in English and Undetermined and held by 29 WorldCat member libraries worldwide.]

On the back of the booklet, Songs For All times, there appears a short essay by George Pullen Jackson, an American musicologist, and educator. Pullen was a pioneer in the field of Southern (U.S.) hymnody and popularized the spurious term “white spirituals” to describe “fasola“* singing. [*fasola= harp singing or shape-note singing] Pullen says

…Sing, preferably your own songs, brother. Live your own song life and be proud of it. Don’t let the I-dont’-know-a-thing-about-music complex trouble you. Don’t let the processed and canned music lower your musical morale. If you are a mature person, re-learn and re-sing the songs of your childhood and youth. (You’ll be surprised at the large admixture of genuine folk songs among your remembered ditties.)

George Pullen Jackson, comment from Songs for All Times [Songs of All Time]

What George Pullen Jackson sensed was the power of music to heal and make joyful the day when it is pulled from routine experiences and even more when it is derived from a shared experience. The shearing of sheep and other communal activities of pioneer families brings home the satisfaction of sharing with neighbors the sometimes daunting tasks that an agrarian life demanded. Further, Jackson in his remarks shares with Cecil Sharp the understanding of the healing power of song as it is remembered across all time and as it derives from the common stories of living.

While there is no direct knowledge of the following song appearing in the original musical repertoire of the Central Appalachians, the sentiment would clearly have resonated with the mountaineers. The Sheep-Shearing, was collected by Cecil Sharp in his 100 English Folk Songs for a good reason. He described it as “very popular among English country folk” and “in existence before 1760.” His sensitive ear could also, no doubt, frame the picture evoked by the lyrics in this and in his other collected songs

THE SHEEP-SHEARING

How delightful to see,

In these evenings in Spring,

The sheep going home to the fold.The master doth sing,

As he views everything,

And his dog goes before him where told,

And his dog goes before him where told.The sixth month of the year,

In the month called June,

When the weather’s too hot to be borne,

The master doth say,

As he goeth on his way:

“Tomorrow my sheep shall be shorn,

“Tomorrow my sheep shall be shorn.”Now as for those sheep,

They’re delightful to see,

They’re a blessing to a man on his farm.

For the flesh it is good,

It’s the best of all food,

And the wool it will clothe us up warm,

And the wool it will clothe us up warm.Now the sheep they are all shorn,

Cecil Sharp, 100 English Folk Songs, …”In existence before 1760.”

And the wool carried home,

Here’s a health to our master and flock:

And if we should stay,

Until the last go away,

I’m afraid ’twill be past twelve o’clock,

I’m afraid t’will be past twelve o’clock.

SEE ALSO

CECIL SHARP AND MAUDE KARPELES Visit to Pine Mountain Settlement School

JAMES GREENE ACCOUNT OF CECIL SHARP and MAUDE KARPELES at PMSS

PETER ROGERS’ ACCOUNT OF CECIL SHARP AND MAUDE KARPELES Visit to Pine Mountain

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH Sheep

FARM GUIDE to Sheep Goats Weaving and Dyeing