Pine Mountain Settlement School

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH

COWS

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH Cows

THE COW

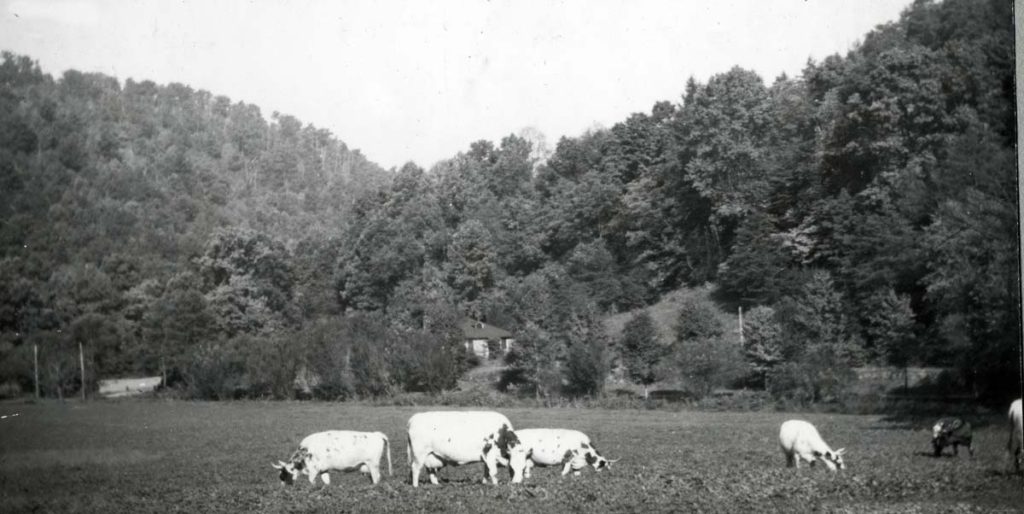

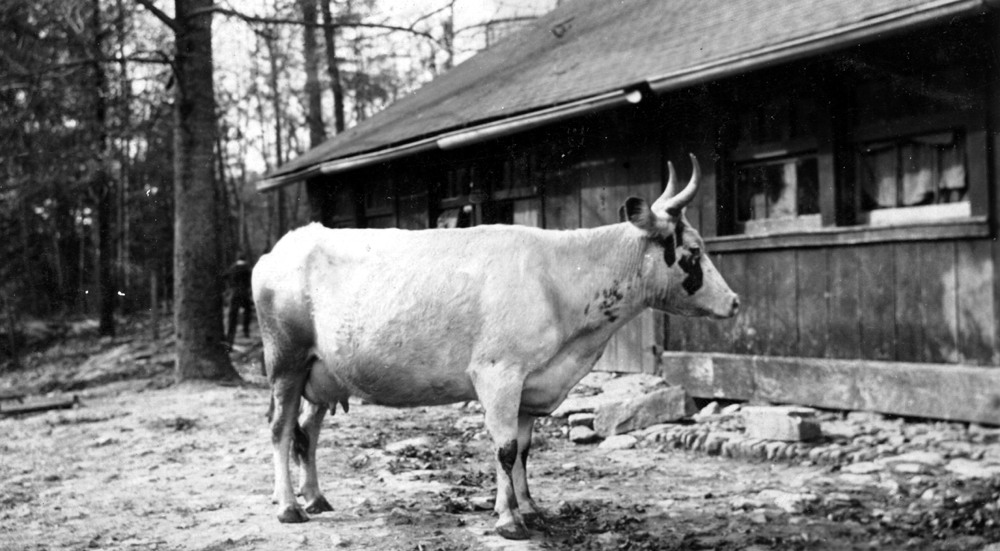

In the collection of the archive at Pine Mountain there is a curious and fanciful scrapbook of everything “cow”. Collected by Elizabeth Hench a member of the Pine Mountain Board of Trustees, the body of material celebrates the ruminating bovine. It is rich in images and quotables, as well as cartoons and paintings that capture moments all too familiar to those who share or have shared their lives with cows. Hench calls her scrapbook, “Joy Made History” and it features the Ayrshires that made up the large herd that became the pride of Pine Mountain Settlement School’s farm. But, that’s a later story. However, one particular fragment in the scrapbook collection caught my eye. It was a chapter removed from a little book of rural reminiscences called Bucolic Beatitudes by the author “Rusticus”. Published in 1925 by the Atlantic Monthly Press of Boston, the little book’s cow chapter was pasted inside the scrapbook. It was titled “Blessed Be the Cow.”

RUSTICUS

This one bucolic fragment by Rusticus calls up memories of the many cows I have known. The chapter charmed my imagination. It describes a chance communion of Rusticus with his milk cow, “Dolly” which changes his day of discontent to one of joy. Because I grew up with cows, it is not surprising to me that the mood change occurred when Rusticus made an unexpected bond with his “contented cow.”

Rusticus, as the author calls himself, had escaped a family gathering and small irritations on his farm by taking a walk. In the hot summer sun, he found a tree in his pasture and languished under its shade. Soon he was joined by the family milk cow, “Dolly” who also relished the shade of the tree. Dolly had ambled to the tree, and begun to chew her cud while curiously eyeing her owner. Both man and cow were soon prone on the grass not far from each other. Dolly chewed slowly on her cud and Rusticus ruminated on the relationship of man to animal as he stared at the contented cow. The following is Rusticus’ short description of their subtle communion

There being nothing else to look at, I looked at Dolly. She was chewing her cud. The slow rhythmic precision of her technique fascinated me. I particularly admired the sideways movement of the lower jaw. She stopped; a gentle genuflection of the neck was noticeable; and she resumed. I had never had a chance to observe a cow before and I made the most of it. I felt that I was seeing for the first time the noble dignity of her head, her broad fine brow, and above all the eyes, serene and beautiful.

Rusticus. Bucolic Beatitudes, Boston: the Atlantic Monthly Press, 1925, pp 58-9

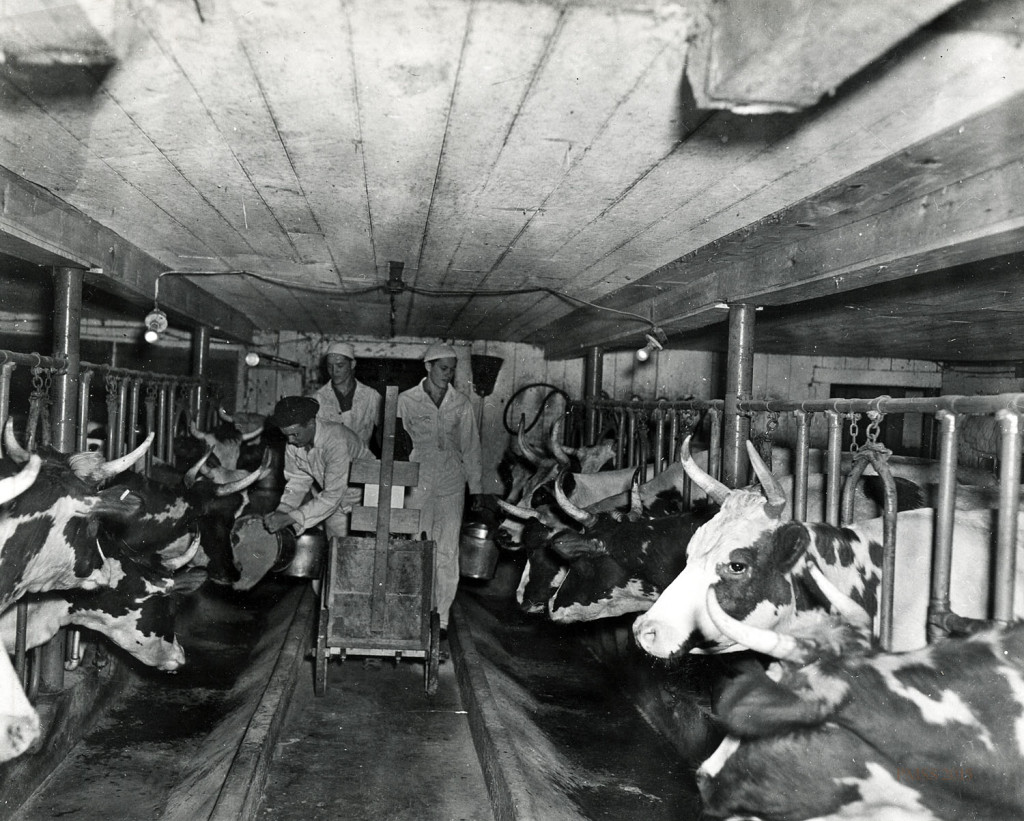

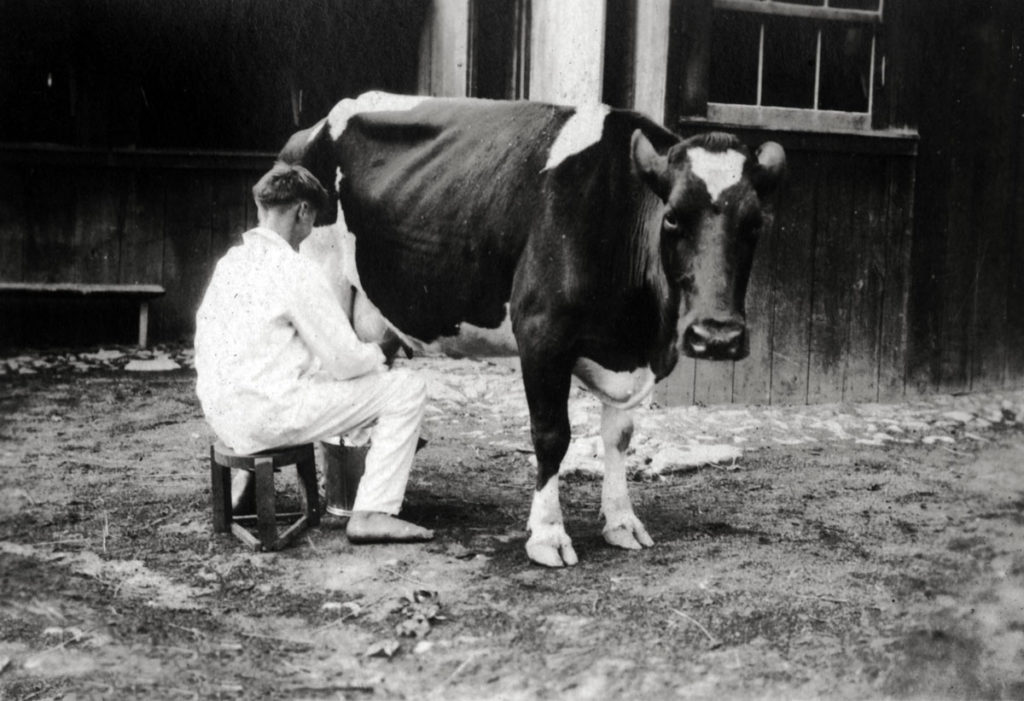

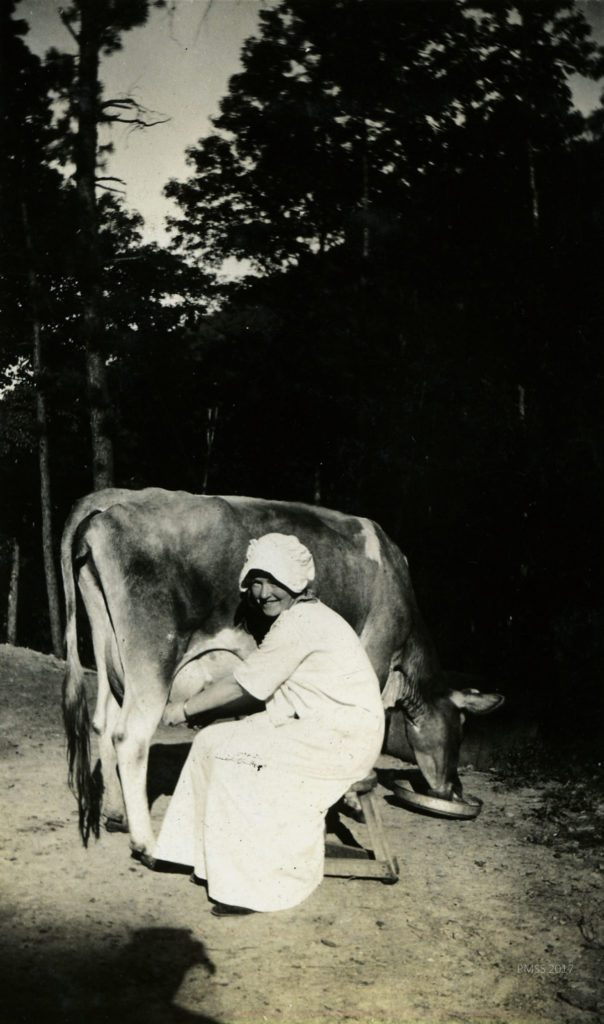

Rusticus continues his observations until the cow stirred, got to her feet and started the path to the barn. It was milk time and a cow feels milk-time calling her. Man and cow ambled slowly to the barn where Dolly is the be milked by a farm hand whom Rusticus calls, “The Incomparable One”. The process of milking that Rusticus so carefully described in this little book is also documented in photographs taken at Pine Mountain in the early years of the School before the Ayrshire herd was begun. Though, I doubt that “The Incomparable One” would have ever shown up barefoot. ‘

Dolly now in place … With hands and arms glistening from recent soapy ablutions, he [The Incomparable One] takes the pail and holds it to the sun. He examines every inch of it critically and with deliberate care … His examination complete, we go where Dolly waits. He takes his place on gently tilted stool; we stand to one side. He pulls his rolled-back sleeves an inch higher, his great firm hands are rubbed together and then the fingers flex in smooth preparatory exercises. He leans forward and gently touches each teat in turn. From each he pulls a tiny lactic stream and lets it fall upon the clean rye straw beneath his feet. This is not done because — as held by some — the first milk contains more impurities than the rest; it is a libation, a propitiatory offering to whatever god there be who presides over the destines of cattle and impecunious rural sentimentalists.

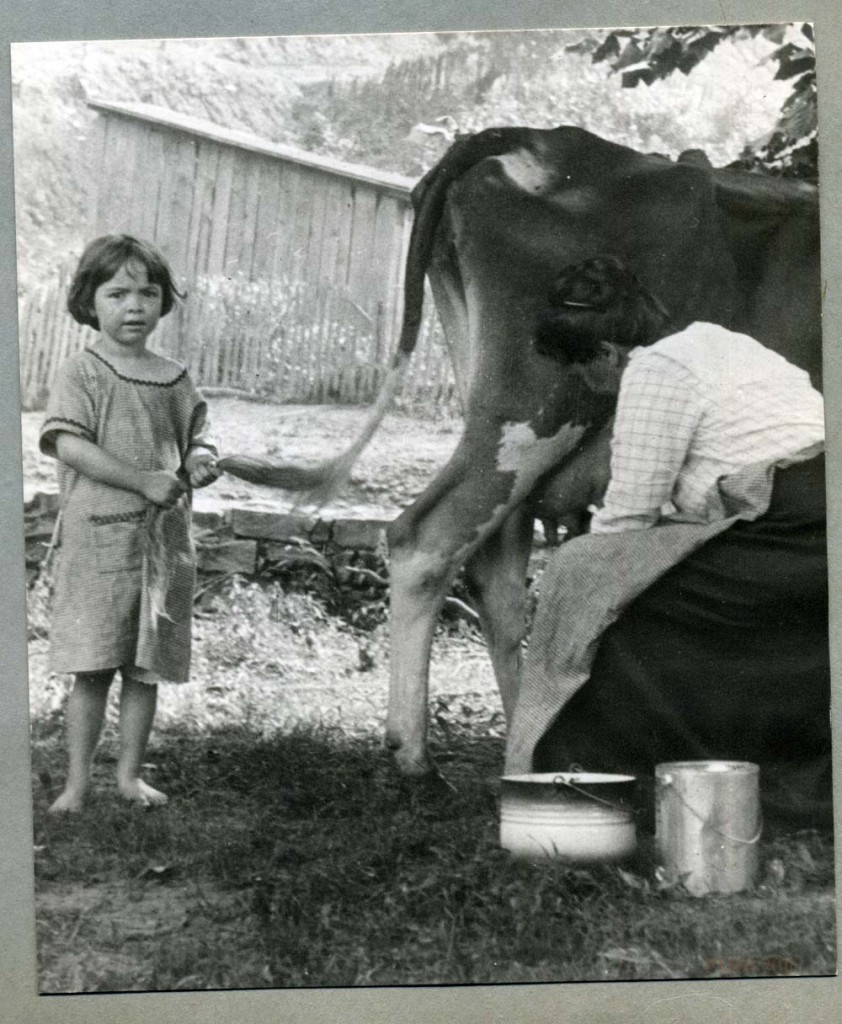

And now the upward glance. A little figure, each in daily turn, takes its place and Dolly’s swinging tail is gently held at rest. The pail is raised to its position between extended knees, and all is ready. I notice that the milker adheres to the proper school. I do not hold, myself, for a position with the forehead of the milker pressed against the bovine flank; rather I like to see the left knee gently touching the off hind leg. It is a satisfaction to see things done with a nice attention to detail.

An now we hear the first streams strike the bottom of the empty pail. The shrill staccato of their impact is the overture, soon muffled by the increasing flood. The cadence slows; we are in the full orchestral swing by now. The milker’s bowed head is slowly raised, and, as the white foam nears the top he looks aloft. He sways a bit on his tilted stool; his head moves gently back and forth like some inspired conductor carrying his musician through the difficult passages of a mighty symphony. And now the beat quickens, the little streams leap into the rising tide of foam with soft lisping sounds. A final volley; then a few soft notes, long-drawn, and it is done.

… ‘Half quart off to-night — the grass is getting dry,” he says.’

Rusticus. Bucolic Beatitudes. Boston:The Atlantic Monthly Press, 1925, p.64-66

The ritual described in this short passage from Bucolic Beatitudes, was repeated over and again on early small Appalachian farms of those lucky enough to own such a gentle bovine ruminator. But the chore of milking was most often accomplished by the woman of the household, not a man.

A humorous mountain ballad captures the load the Appalachian woman often endures in house and on farm. It also calls out the relationships that cows often make with the milker. Cows, like people come with attitude and some cows are not quite so cooperative or bucolic as Dolly. The following brief stanza from “The Old Man in the Wood,” that I sang as a child, describes what happens when the man of the household brags that he can “… do more work in a day, than his wife can do in three…”

THE OLD MAN IN THE WOOD

There was an old man who lived in the woods

As you can plainly see

Who said he could do more work in a day

Than his wife could do in three

“If that be true,” the old woman said,

“Why this you must allow:

You must do my work for one day

While I go drive the plow.”

“Now you must milk the tiny cow

For fear she shall go dry

And you must feed the three little pigs

That are within the stye

And you must watch the speckled hen

For fear she’ll go astray

And you must wind the reel of yarn

That I spun yesterday.

The woman she took the staff in her hand

And went to drive the plow

The old man took the pail in his hand

And went to milk the cow.

Tiny hitched, and Tiny switched

And Tiny cocked her nose

Tiny gave the old man such a kick

That the blood ran down to his toes….etc

After failing to complete all the other tasks he said of his wife

Yes, he swore by all the leaves on the trees

And all the stars in heaven

That his wife could do more work in one day

Than he could do in seven.

Jean Ritchie. The Swapping Song Book, Lexington: Univ. Press of KY, and collected by Pine Mountain Settlement School in the PMSS Song Ballads and Other Songs printed and published by Pine Mountain Settlement School.

Many of the nine Ritchie Family children attended Pine Mountain Settlement School and also nearby Hindman Settlement. Jean attended public school and the University of Kentucky later becoming a well known folk singer. See PMSS records for May Ritchie, Truman Ritchie, Patty Ritchie, Una Ritchie, Kitty Ritchie.

Cow tales abound in the Pine Mountain literature. And cow tails figure in many of the tales. When Tiny “twitched and Tiny switched” that was in reference to the switching tail used to dispense the many flies that often troubled the summer milk cow as well as troubling the milker. When Rusticus described the “little figure” coming to help the “Incomparable one,” he was, no doubt referring to some child assigned to this task. The photograph below, demonstrates the firm grasp of the tail which keeps it under control for the milker to progress.

FIRST, YOU HAVE TO FIND THE COW

Not only is milking a challenge, first, in the early years, one had to find the cow. Before range laws were in place, cows roamed freely in Appalachia and in other places in the Country. The cows were generally fitted with cow bells to more easily locate them. The bells were not just auditory ornaments, they were a GPS system that children could use to correlate cow and sound. Before the cow could be milked it had to be found and brought in for milking and be secured for the night. The following story by a Pine Mountain School student (unnamed) describes the task of finding the cow — a chore often assigned —- like tail holding — to children.

AS I LOOK BACK

Oh, how I dreaded to see the time come just at sun set to hunt the cows, call up the dog and start up the hollow! How far it took, for the old belled cow was way up in the weeds and briars as far as she could get. I can still pant from climbing that steep hill knowing I would have to hunt for two hours maybe before I found them all. When I started from the house to get them, old Pide’s bell could be heard very distinctly but when she heard me coming not a tap of the bell would she make. Finally the dogs would find them all and down the hillside they would come with clouds of dust behind them, for they feared the sharp incisors that would clinch their legs. There was a reason why he never bit their tails; they were always too high in the air. Oh! how I dreaded to get ton the gate with those cows for there were those pigs making their way like a terrific storm and we knew if they got out it would be another trip to the pasture field.

But sometimes we climbed up the cow pasture on our way to the Pine Knobb cliffs. There in the valley the house stands where the creek forks like a turkey’s foot. My mother and father are still living in it. Although on the cliffs we were a mile away, all that stirred around our house could be seen. Far, far away in other directions we looked into yet other valleys. At our feet were lovely tree tops where birds hopped from limb ton limb and from one tree to another. When the sun hid behind the hills we started homeward. When we reached the big rock we would have to stop to satisfy our hunger from the store of walnuts we had gathered there. I’m sure our cracking stones are still in place. It was those times of fun we had cracking walnuts that made the thought of getting the cows, that never came by themselves, a little softer in my mind.

Anonymous. The Pine Cone 1937 Pine Mountain Settlement School newsletter.

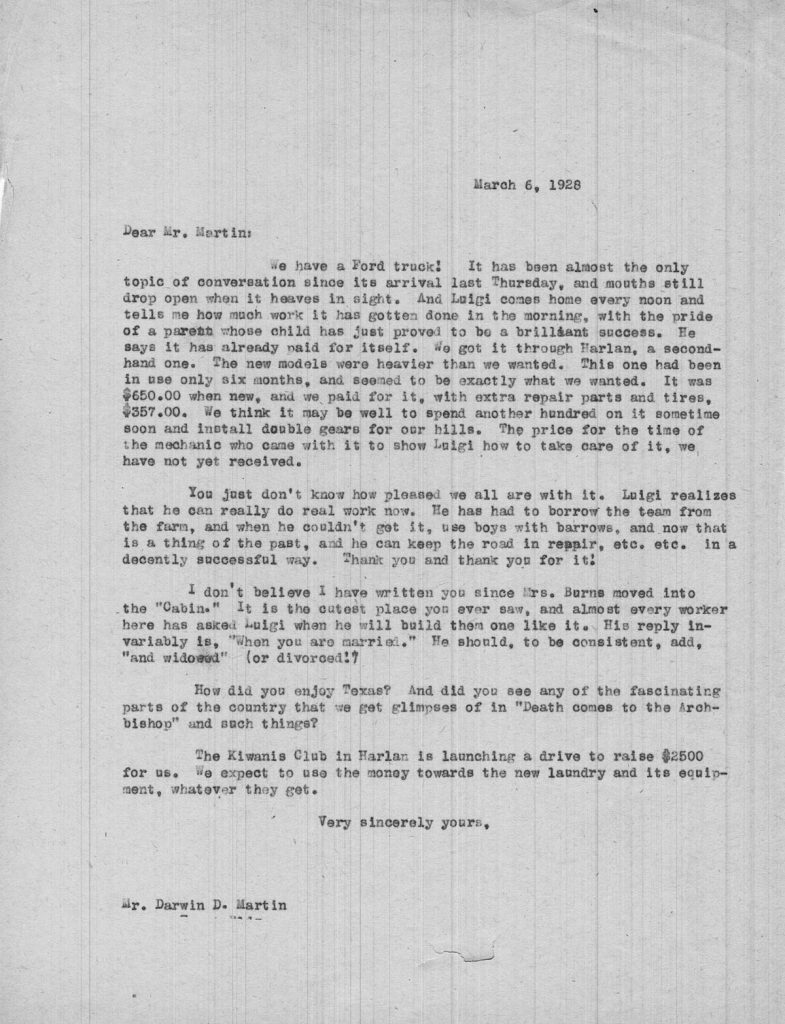

And, that brings us back to Elizabeth C. Hench and her Joy Stock Company Limited Letters 1927-33. The following is the last letter in her series of letters to those who so loyally supported the Ayrshire herd at Pine Mountain for many years. It is a fitting letter as it returns to the emotional contributions of the cow to the world. Written near the end of the Great Depression, the letter is edgy with humor and anxiety.

The grand Ayrshire herd at Pine Mountain Settlement would last only a few years after the closure of the boarding school. When the expense and the labor to support the program and the new regulations regarding milk production came into play, the dairy herd was no longer viable. When the last of the herd was sold the cow bells had been silent for many years and the gentle communions with our ruminating neighbors were infrequent. Cows in Appalachia have now been replaced by the deer and by the elk that roam freely. But, none of those will summer nap with you under the same tree or will share their milk, or mellow your mood …

LETTER TO THE MEMBERS OF THE JOY STOCK COMPANY LIMITED 1933

Dear Stock-Holder:

Ordinarily I am as restless as a short-tailed bull in fly-time until I get the autumn cow letter off. But during the summer just past, to those of us in this section of the world, autumn, with its many days or rain, brought no terrors. As we oozed and mopped, we looked in vain to cows for relief. For, do you know, cows are weatherwise? Here are some of the signs:1 — If a bull goes first to pasture, it will rain.

2 — If cattle lie down at once when they reach pasture, they want a dry bed before rain starts.

3 — If a cow licks a brick wall, rain will fall.

4 — If a cow lies down on her right side, rain will come soon.But cows went placidly and contentedly on their way. What matter to them if springs went dry and creeks fell? The cow with the iron tail would supply them!

Contentment is so often spoken of as a characteristic of cows, that a quatrain I found does not ring true:

“The Worry Cow would have lived till now

If she had only saved her breath,

But she feared the hay wouldn’t last all day,

So she choked herself to death.”Nevertheless, if the Joy Stock Company, Limited, and REJOICE, our cow, don’t have checks, we’ll be ready to sing The Tune The Old Cow Died On —

“There was an old man, and he had an old cow,

And he had no fodder to give her,

So he took up his fiddle and played her this tune:

‘Consider, good cow, consider,

This isn’t the time for grass to grow,

Consider, good cow, consider.'”Those of us who have ridden along the main highways have been enjoined by huge posters to roll our own, but how can REJOICE roll her cud without food?

If there be (notice the conditional tense) any of us whose incomes have not been slashed, and if there are any of us who can squeeze out a little money, let us send our checks soon.

From one who tries to keep the Milky Way

always visible at Pine Mountain,[Signed] Elizabeth Hench

P.S. Did you realize that Amelia Earhart Putnam’s landing in Ireland was witnessed only by a herd of frightened cows?

https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=17147

SEE ALSO:

ELIZABETH C. HENCH Joy Stock Company Limited Letters 1927-33

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH The Dairy

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH Farm and Dairy Early Years