DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH

Series 13: EDUCATION

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION

At PMSS Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

TAGS: Environmental Education at PMSS, Bickford State Nature Preserve, hemlocks, natural resources, conservation, science education, elementary and secondary environmental education, adult environmental education, AI-generated images, virtual classrooms

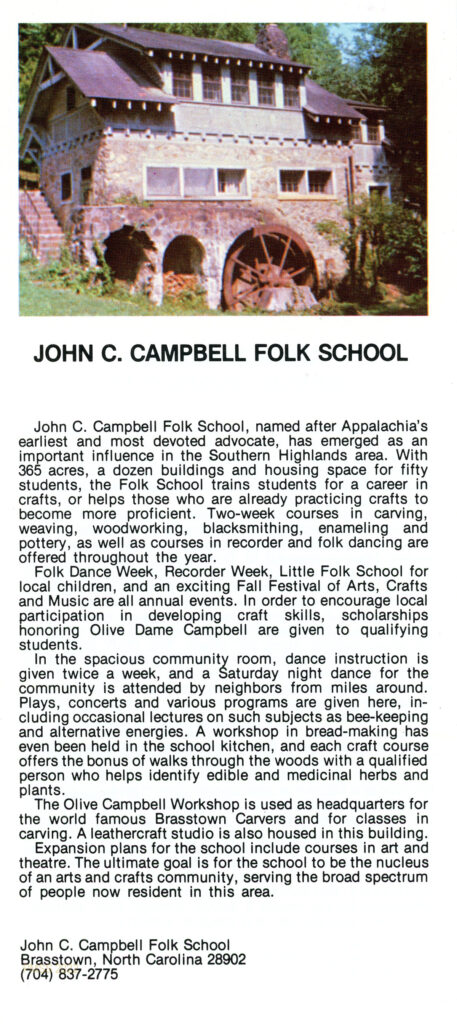

Environmental Education programming at Pine Mountain is deeply indebted to the foundations of the original ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION program, conceived in the 1970s. The early program served a range of schools within and outside the state of Kentucky. Reaching more than 3,000 children each year, the early programs strived to educate our future natural resource stewards. The programming today follows the original founding philosophy and has been expanded to include adult programs, workshops, and retreats that utilize the rich ecology of the school setting.

In addition to the School’s work with educators, the School is charged with preserving the 800-acre Bickford State Nature Preserve, including the removal of invasive species such as the invasive woolly adelgid on the local hemlock trees and the pervasive spread of multiflora rose.

The current environmental programming at the School may be followed on the Environmental Education pages of the Pine Mountain Settlement School’s main website.

Environmental Education. Ben Begley teaches students to use a crosscut saw. Early 2000. [EE_Picture2.jpg]

When the world made a leap into the future with AI (Artificial Intelligence), the editors of this website queried AI about the future of Environmental Education using the phrase, “futuristic environmental education class”. Specifically, we asked what the future would look like in a new AI “eco-friendly classroom” at Pine Mountain. The results were startling — but not. Consensus? Spelling? : AI may need to go back to school when exploring environmental education’s future.

AI generated image of Pine Mountain Settlement School Environmental center. [e2fd1d33-f389-4531-a577-2ab3894d917a.jpeg]

[OIG.jpeg]

In the futuristic visions, the grass is green, but the images are dystopian. The spelling ?? is derranged. If you do not know what “dystopian” means, then you may try to look up (“futuristic education”) in the new APP (application) in an AI search. After that quick look-up, you might try to contemplate what kind of future YOU desire or are perhaps beginning to live within. Think deeply. You perhaps may find “your virtual self ” walking out a screen door into a forest, where the “virtual you” sits beside a stream, gazes on a sunset, perhaps camps among the wild creatures, or marvels at the change of the seasons. Or, perhaps the “real you” may open the door to a virtual environment where you explore virtual rainforests, Antarctica, African deserts, or other parts of the globe. It may be a time when only your virtual self can survive the new environmental world. The real outdoors may no longer welcome the real you.

Perhaps the new virtual “outdoors” will prevent us from freezing, overheating, or gasping for breath. But it may also permanently alter our relationship to our surrounding world. In the new virtual world, we may be forced to interact with our environment through virtual tools. We may look out onto a new world where our children will no longer be safe in unstable or even hostile outdoor environments. Distracted and educated by the rapid advancement of virtual life, we may fail to sense the dangers of not living within nature. We may fail to curb our appetite for entertainment, and, critically, fail to understand the “tipping points” in our planet’s growth and our appetites. We may become too distracted and entertained to see our role in our mandatory environmental stewardship.

What will environmental education look like in the future? We asked AI: “What is the future of outdoor education for children?” AI answered:

-

- Increased Emphasis on Sustainability and Environmental Stewardship: Growing concerns about climate change will lead to a greater focus on environmental education. Programs will become “living laboratories” that teach children about ecosystems, conservation, and sustainable practices, fostering a sense of responsibility and connection to the planet from a young age.

- Integration with Academic Subjects: Outdoor learning will move beyond an enrichment activity to a core part of the curriculum, integrating subjects like science, math, history, and literature into real-world, hands-on experiences.

- Focus on Mental Health and Well-being: As mental health issues and screen fatigue become more prevalent, outdoor education programs will place a stronger emphasis on promoting well-being. Time in nature is proven to reduce stress, improve focus, and build resilience and confidence, making it a crucial component of holistic child development.

- Incorporation of Technology: While the goal is often to unplug, technology will play a supplementary role. Tools like GPS for navigation, location-based apps for learning about local flora and fauna, and virtual reality for accessing remote environments will enhance outdoor experiences and safety.

- Increased Diversity and Inclusivity: Efforts will continue to make outdoor education more accessible to underrepresented groups, addressing issues of cultural sensitivity and disability access. The goal is to democratize nature and ensure all children, regardless of background or location (including urban areas), have opportunities to learn outdoors.

- Creative Use of Urban Green Spaces: In response to urbanization, innovative approaches will transform urban landscapes into learning environments. This includes using rooftop gardens, pocket parks, and repurposed vacant lots to integrate nature into city living.

- Adventure-Based Learning and Risk-Taking: There will be a continued recognition of the importance of “adventure play” and acceptable risk-taking in child development. Activities involving climbing, balancing, and exploration will be encouraged to build problem-solving skills, physical literacy, and confidence.

Both on target and off, the responses are important to consider.

THE VIRTUAL CLASSROOM

AS the AI-generated query and suggestion list continued, it provided an additional adaptive programs list. The AI adaptive responses were encouraging, but they appeared to assume that the existing environment would be accommodating and relatively stable. Clearly, that future scenario does not appear to be the evolving climate direction. Outdoor activity will surely be more frequently disrupted under the current weather projections. The temperature rise and the associated instability may be too far along to stop. Other negative trends may be too far along to realistically halt. Conflicts may accelerate environmental degradation.

The virtual environmental classroom will certainly be of use to scientists looking for solutions to our environmental downturn — and a welcome intervention. But, how do we educate for this? What does that education look like? What difference will we see?

IF the VIRTUAL outdoor classroom points us toward our future, what do you think those virtual lessons will teach? Should teach? The following experimental image was created when AI was instructed to create an environmental education classroom in the future. While the images and the narrative below may be exaggerated, they are there to remind us of our choices and the education and lessons that inform our choices.

AI generated image of Environmental Education Class in 2050. [OIG.jpeg]

[ffa9fdae-d7f7-4ebb-abf0-0f7f4918301a_stream–ecology (1).jpeg]

And an “outdoor” classroom …

[8479ea0e-9037-45f0-b583-ce6527a55bc3.jpeg]

The lessons found in REAL outdoor classrooms abound at Pine Mountain Settlement School, and the educational lessons to be found in the physical environment of the School are unlimited. Many of the lessons are critical to our survival as a species and can only be learned within the OUTDOOR classroom. Sure, you can look to the future of the “eco-friendly” classroom through a headset, seated in a “plastic” chair, or you can look longingly toward the “grove” of trees in the top right corner of your small window view! YOUR relationship to your environment is your choice. But, outdoors is still — outdoors.

PICK UP YOUR FEET

Real outdoor education requires that you pick up your feet and walk the trails. There are no sidewalks. It requires that you leave the rare salamander under the leaves. It recommends that you ask where your water comes from. At Pine Mountain Settlement, it requires that you drink water filtered by million-year-old limestone rocks, and you share meals made with home-grown salads. It recommends that if you want to hike the “Summit Trail” you need to be in good physical shape. Outdoor education for early settlers of the area was not taught in a classroom; it was a way of life for the early settlers of the area.

If the cow did not come home to be milked, the early families listened for the sound of a familiar bell and climbed the mountain to search for their cow. Today, if you reach the “Summit” of the Pine Mountain ridge and watch the sun set or rise, you will be surrounded by beauty, hope, pride, and perhaps, ancestors who made that climb daily. In the outdoor classroom of the campus, the experience of environmental education surrounds the visitor. Educators know that educating is imperative, but they also realize that their understanding is selective. Contributions to environmental education can come in many forms, and these forms will shape our shared future. Pine Mountain provides a wealth of environmental lessons for instructors.

In the valley below the Summit, students learn lessons from the critters at the school. The sheep, goats, bears, and groundhogs, and possibly the campus dog, will contribute to your understanding of nature if you observe carefully. For example, one can wonder at how the smartest guardian of the School’s environment, “Lady,” the campus dog, knows to dive into the warmth of a pile of leaves on the cool days of November. And, you may learn why knowing the native plants could keep you from starving or dying. If you ask why there are no bees in the hives, you will find that the bee hives have trouble with hungry bears. If your question is why vegetable “tunnels”, rare plants, and rare ideas can all grow together. The answers may take some time, but they may carry a myriad of lessons.

The outdoor joys of a day in Spring, Summer, and Fall will linger with you after you leave the campus. Perhaps you will find yourself remembering how a small corn-snake feels on your hand — or not. How the gentle pinch of a crayfish says “Put me back in the stream”. How a very small “chigger” insect can pack a mean bite in the summer blackberry patch and keep the victim awake all night. Nature is at its best when it can physically remind us that we live within it, and we need to educate ourselves for survival. So many real memories from nature, each tuned to the environment and to the seasons as they shift, help us all to shape how we treat this precious global home we share and, even more importantly, how we share and care for the future of each other.

See Also:

Environmental Education Resources at PMSS Today

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Staff 1972 to Present

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION 1972 – Present Bayside Academy and Pine Mountain Settlement School

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION 1983 EE Operations

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION A Legacy for Future Generations

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Brochure 1

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Brochure 2

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Case Statement Nature-Culture

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Green Book 1974

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Lesson Plans and Supplementary Information 1973-1995

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Personnel Chart

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Pine Mountain Bird Checklist

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION PMSS 1997 Wellhead Protection Plan 1997

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Split Rock Nature Loop Trail Guide

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Stream Ecology Hopscotch Mosaic

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Student Groups at PMSS

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Flowers

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Salamanders

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Scott Matthies EE Narrative

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Warblers

LOREN W. KRAMER 1970 First Earth Day at Pine Mountain Settlement School

LOREN W. KRAMER Notes on Educational Planning at Pine Mountain School 1968-70

PINE MOUNTAIN STORY – CH. II

MARY ROGERS 1977 GOVERNANCE Philosophy of PMSS

MARY ROGERS EE Planning and Programming Notes

MARY ROGERS Tribute by Milly Mahoney 1998

NANCY SATHER Correspondence 1969 Educational Planning

NANCY SATHER Staff and Trustee

PERIODICALS Castanea Journal of Southern Appalachian Botanical Club

PUBLICATIONS RELATED 1968 Effects of Surface Mining on Fish and Wildlife in Appalachia

PHOTOGRAPHS

027 PHOTOGRAPHS V ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Classes and Trails

028 PHOTOGRAPHS V ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Geology and Fossils

029 PHOTOGRAPHS V ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Indians and Settlers

030 PHOTOGRAPHS V ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Miscellaneous

031 PHOTOGRAPHS V ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Water

033 PHOTOGRAPHS V ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION People and Groups

EVENTS

EVENTS Guide to Ongoing Annual Events

EVENTS ANNUAL Fall Color Weekend 2005

EVENTS ANNUAL Lucy Braun Weekend

EVENTS ANNUAL Spring Flower Weekend

EVENTS ANNUAL Fall Color Weekend

…and more

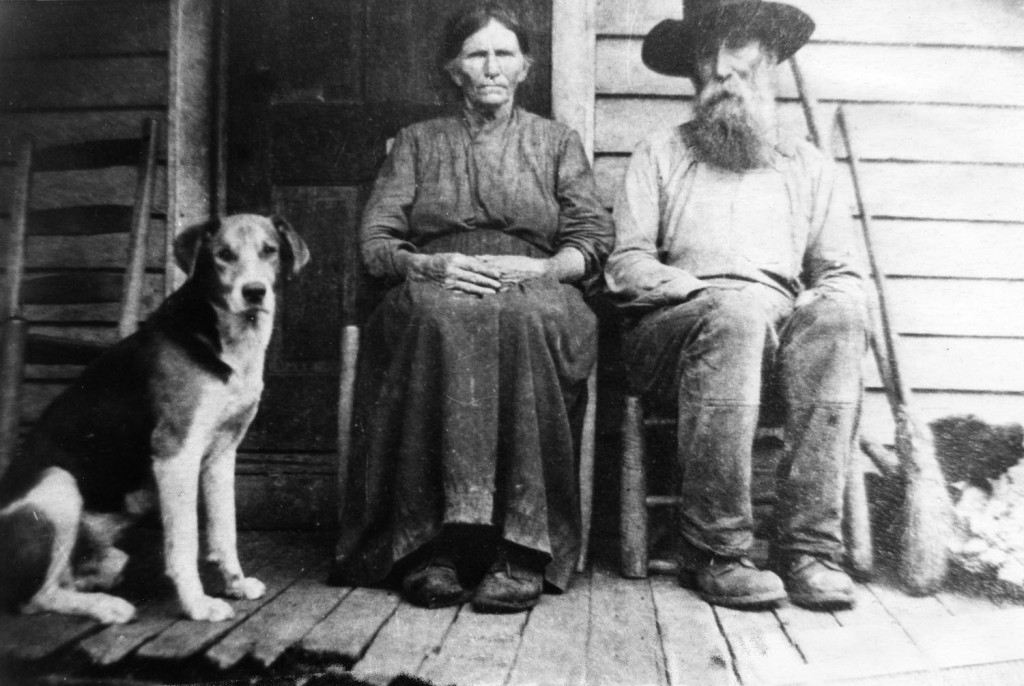

HOUNDS 418 Boy and young man seated with two hunting dogs. Ship-lap wall behind them.

HOUNDS 418 Boy and young man seated with two hunting dogs. Ship-lap wall behind them.