Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 04: ADMINISTRATION

Series 09: BIOGRAPHY

Katherine Pettit, Co-Founder & Co-Director, 1913-1930

Katherine Rebecca Pettit (1868-1936)

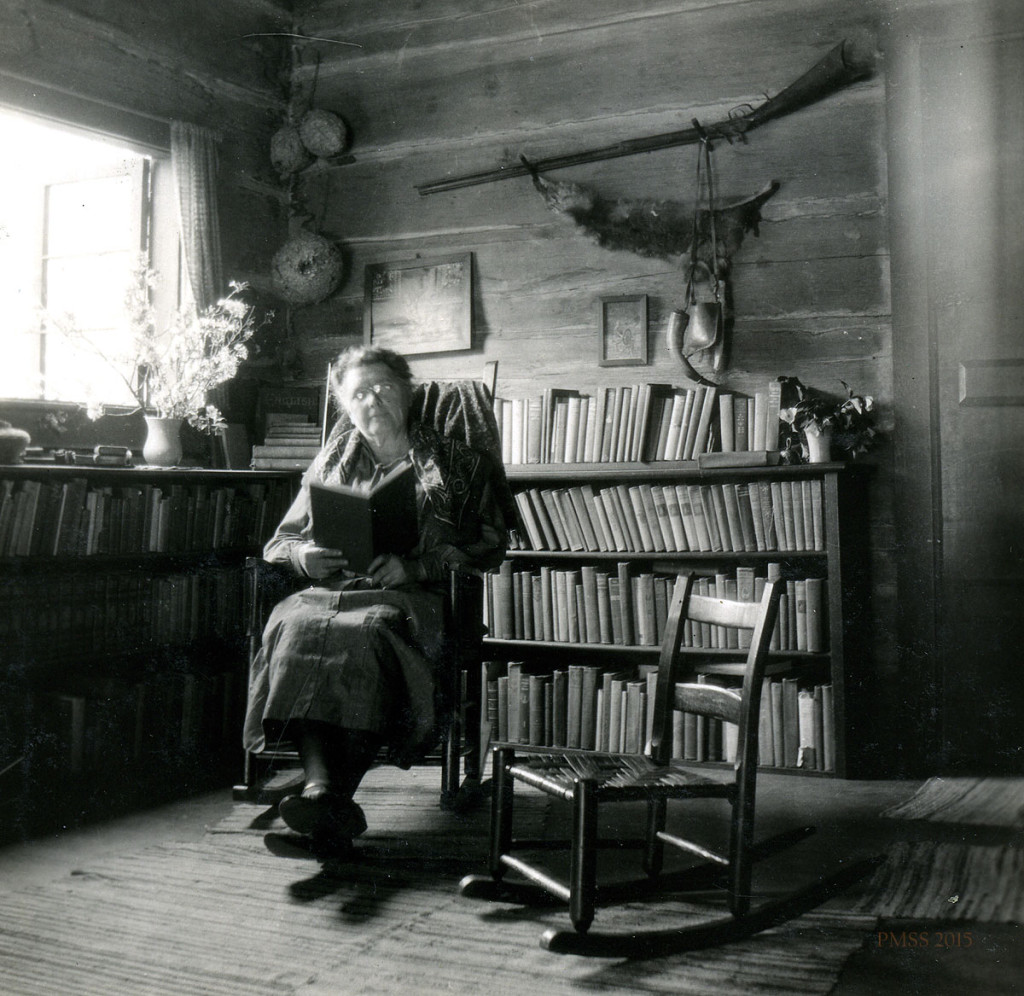

Katherine Pettit at Big Log. [kingman_046b.jpg]

TAGS: Katherine Pettit, Katherine Rebecca Pettit, May Stone, Clara Mason Pettit, Benjamin F. Pettit, Pine Mountain Settlement School, founders, Ethel de Long Zande, Ethel de Long, Mary Rockwell Hook, weaving, Kentucky Women’s Clubs, State Federation of Women’s Clubs, Hindman Settlement School, Rev. Lewis Lyttle, William Creech, Sally Creech, Harriet Butler, Eve Newman, Alice Cobb, Emma Lucy Braun, forests, old-growth forests, Kentucky Primeval Forest League, environmentalism, Women’s Christian Temperance Union, WCTU, South America, Ruth Huntington, Lucy Furman, Blossom Lady

KATHERINE PETTIT Director

Administrative Staff: Co-Founder & Co-Director 1913-1930

Katherine Rebecca Pettit (1868-1936)

Early Life

Katherine Rebecca Pettit was born on February 23, 1868, the child of Clara Mason (Barbee) Pettit (1846-1880) and Benjamin F. Pettit (1838-1890). Benjamin owned an expansive, profitable farm in Lexington (Fayette County), located in the Bluegrass region of Kentucky. As of the 1880 U.S. Census Benjamin Pettit, age 42, was a widower with 4 other children besides 11-year-old Katherine (“Katie”): Martha (“Mattie” 9), George Nathaniel (7), Lillie (5), Minnie (3) and Benjamine (sic), 6 months.

Miss Pettit attended schools in Louisville and Lexington, including two years (1885 – 1887) at Sayre School in Lexington, then known as the Sayre Female Institute. After involvement with the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and the State Federation of Women’s Clubs, she left both to advance her career as a progressive educator.

Her past associations with the State Federation of Women’s Clubs served her well. Not only did the Kentucky chapter inspire her to find ways to ease the hardships that Kentucky mountain women endured within her state, but it also provided her with a network of contacts for fundraising and sponsorship. She had first-hand knowledge of the work of Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr, who co-founded Hull House, an urban social settlement house in Chicago, and was, also influenced by the earlier Settlement Movement in England. Throughout her social work efforts, Pettit borrowed and built upon the principles developed within the Settlement Movement. She was particularly influenced by Chicago’s Hull House principles of “social justice, fairness, tolerance, respect, equal opportunity, civic responsibility, and hope for every individual, family and community.”[citation]

KATHERINE PETTIT at Hindman Settlement

From 1899 to 1901, Katherine Pettit and May Stone, Wellesley (MA) College graduates from Louisville, volunteered to work with educational programs that were set up in tents each summer by the Kentucky Federation of Women’s Clubs. First at Camp Industrial (Knott County), then at Camp Cedar Grove in Hazard (Perry County), and later in the re-named Sassafras Social Settlement (Knott County).

During their three summers at the camps, Pettit, Stone, and a committed group of women saw a great need to improve the living conditions, education, and health of the people in the eastern Kentucky mountains. According to Rhonda England in her paper, “Bringing Modern Notions of Childhood and Motherhood to Pre-industrial Appalachia: Katherine Pettit and May Stone, 1899 – 1901,”

While the women found many of the older, more traditional aspects of Appalachian culture preferable to the changing values in the more industrialized areas, they also found many elements in the culture that were backward, especially as they affected health and education. In order to help the mountaineers become self-sufficient, the women believed they should teach the people to make the best use of what they had.*

*See also: Jess Stoddard. The Quare Women’s Journals, Ashland, KY, 1997 and remarks on Rhonda England. “Voices From the History of Teaching: Katherine Pettit, My Stone, and Elizabeth Watts at Hindman Settlement School.”

By 1902, Pettit and Stone had raised solid funding and, under the auspices of the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, they established the WCTU Settlement School in Hindman, KY. In 1915, the School was incorporated and renamed the Hindman Settlement School. This early rural settlement experiment became the incubator for Katherine Pettit’s development of Pine Mountain Settlement School.

A New Project in the Pine Mountain Community

In 1911, The Reverend Lewis F. Lyttle, an old friend and supporter, introduced Katherine Pettit to a local mountaineer, “Uncle William” Creech Sr., who wished to donate land in a remote area of Harlan County for a new school that would address the area’s lack of educational opportunities and moral guidance.

With this incentive, Miss Pettit, along with Miss Ethel de Long, a New Jersey native who was a Smith College graduate and who had worked as a principal at the Hindman school for two years, began their new project in Harlan County. By 1913, they had sufficient momentum and support from both Hindman and from the Pine Mountain community to found the Pine Mountain Settlement School.

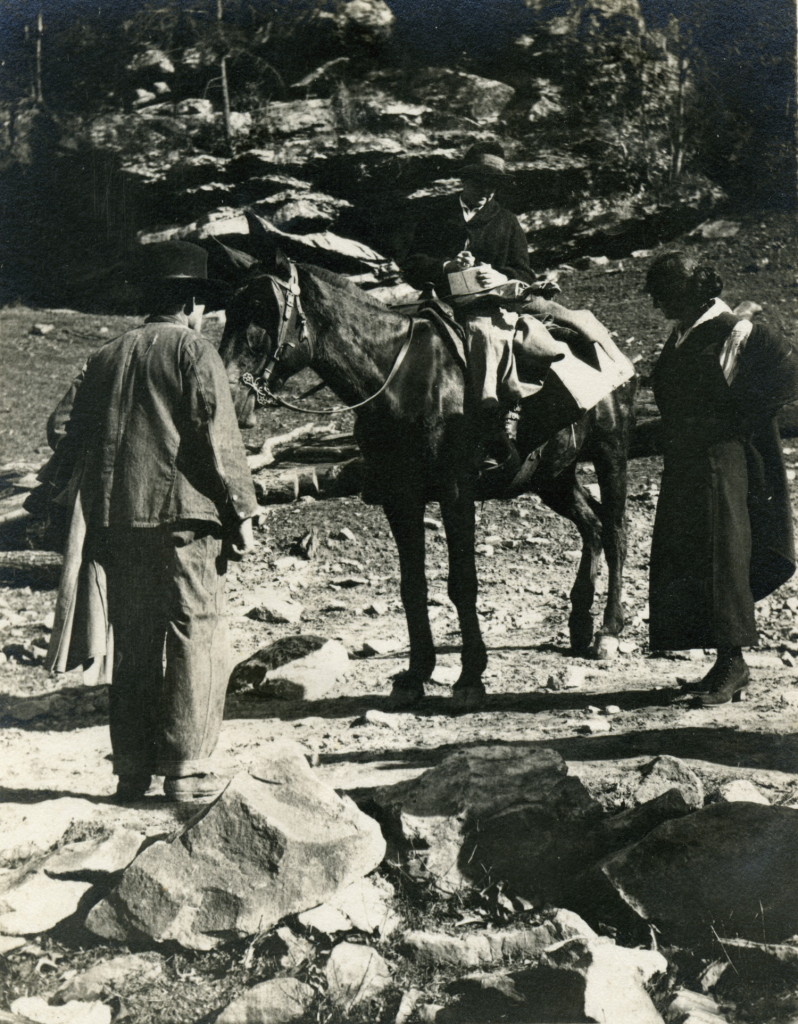

Miss Katherine Pettit, seated on horse with man and woman standing nearby on road below Indian Cliff dwelling at School entrance. [date unknown] [X_099_workers_2494_mod.jpg]

KATHERINE PETTIT and the Creation of a National Heritage Site

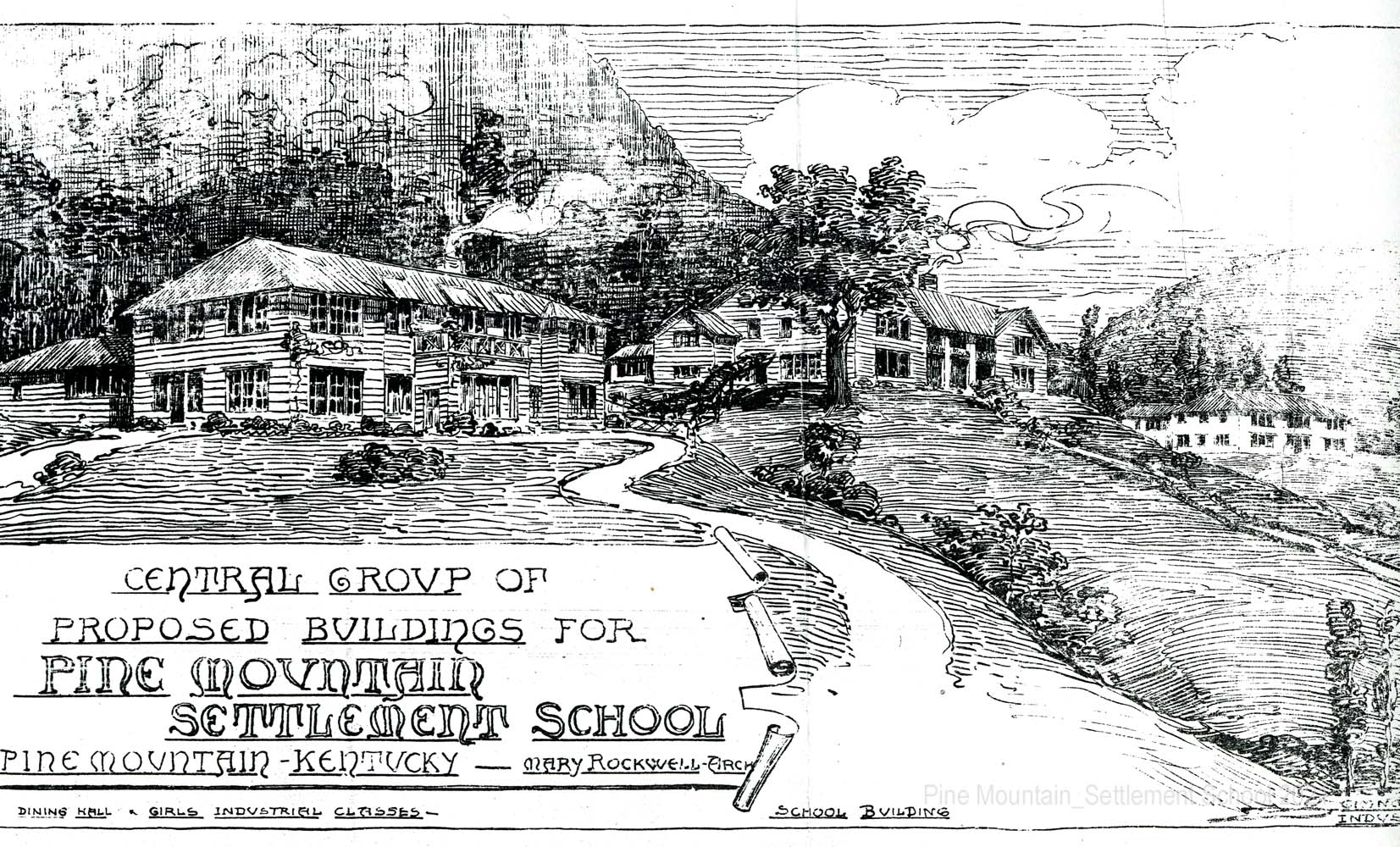

Miss Pettit’s strength, energy, and farm experiences as a child suited her for supervising the important building development and preparing the new land for farming. As she supervised the early work of clearing the land, planting crops, the physical construction of buildings, and the landscape, she also saw to it that the natural beauty of the land was disturbed as little as possible. She had never been happy with the rapid and somewhat haphazard building and rebuilding of Hindman after a series of disastrous fires. Her executive assistant, and co-director, Ethel de Long, also had an eye for the aesthetics of place. She managed the structure of the educational program, the day-to-day management of the evolving institution, and the two women shared the hard work of fundraising.

The new directors recruited, via friends, the architect Mary Rockwell Hook, a graduate of Wellesley College and a former student in the architectural atelier of Marcel Auburtin in Paris, France. Hook, with Pettit and de Long, devised a comprehensive plan for siting the buildings within the pristine landscape of the valley. Hook was just the catalyst needed to join the vision of the two co-directors and to enlist other capable staff to grow the architectural master plan of the School. Her assistance with the campus layout and new buildings was as energized as were the efforts of Pettit and deLong. It was a dynamic trio.

Cropped image of the original Mary Rockwell Hook drawing for Pine Mountain Settlement School.

Hook readily adopted the grand views of Pettit and de Long, but she brought a contemporary overlay and a community spirit and a modified Arts and Crafts vision to her architectural and landscape work that produced one of the most unique environments of any of the growing number of rural Settlement Schools. The first Pine Mountain building that Mary Rockwell Hook designed was a rustic log home for Miss Pettit and the first children students. It utilized the historic building materials and the essence of the mountain cabin, but on a grand scale. Today, the careful work of Pettit, de Long, and Hook is recognized by the site’s designation as a National Historic Landmark (NHL). These sites are selected to represent an outstanding aspect of American heritage and history and to illustrate the heritage of the United States. Pine Mountain Settlement does this with great style.

The Unique Tenacity of Katherine Pettit

Ethel de Long, in her role as founding co-director and school principal, and chief executive, began the difficult task of establishing a School. Academics and fundraising had their base in the lessons learned at Hindman, but though similar to those at Hindman, she also gave the new educational programs stronger roots in the most progressive educational philosophies. The Pine Mountain educational program then collected the best lessons of the Hindman experiment in industrial arts and Progressive educational principles. Pettit then added an emphasis on medical assistance and training, an enormous community need. Pettit’s industrial arts interests, de Long’s unique approach for basic educational preparation, and the added emphasis on community medicine were exciting and attractive in combination for the people in the Pine Mountain community. Together, the two co-directors drew up a mission that today has shifted very little from the fundamental ideas of the two co-founders and that has sustained the institution for over one hundred years.

The unique built environment, the deeply researched and smart educational program in the remote region, the arts and crafts-focused industrial training program, and the integration of the long and familiar heritage of a proud people and their proud heritage were solidly sustainable. As a women’s initiative, Pine Mountain Settlement School remains an extraordinary success at convincing educated and wealthy donors to give to the School, providing a sound financial base that has sustained over time.

Both Pettit and Ethel de Long encouraged the local community and all Appalachian people to be proud of their heritage and to work to preserve their arts, folk songs, and customs. For example, Miss Pettit honed her knowledge of raising sheep, spinning wool, weaving traditional patterns, and using natural vegetable dyes from families who still practiced the old traditions, and she then taught these skills to younger women and children who had not been exposed to these crafts. (The dyeing practices were recorded in The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes by Helen Wilmer Stone Viner, who worked as a housemother for six years at Pine Mountain Settlement School and recorded Pettit’s research into natural dyes. (In 1946, after moving from Kentucky to Saluda, North Carolina, Miss Viner married, and she and her husband published the 63-page book that is based on her work with Pettit and is based on the dyeing practices Pettit had learned from the community. Viner’s book is a classic on the subject of vegetable dyeing and is dedicated to the memory of Katherine Pettit.)

Motivations in the Life of Pettit

While the strength of Katherine Pettit’s will cannot be disputed, and her contemporaries rarely called into question directly while she was building the institution, later historians have begun to explore her motivations. Just where did she draw her strength and her ideas that drove her to head for the mountains of Eastern Kentucky? The where and the why are not easy to answer and even more difficult to firmly define. No full biography has been attempted of her, leaving Jess Stoddart’s book, The Quare Women’s Journals, 1997, to reveal what it will to the reader of Pettit the person. There continue to be many “probably,” “possibly,” and “perhaps” qualifiers interspersed in any evaluation of her and her work. For example, David Whisnant in All That Is Native and Fine (1983) painted a strong picture of a woman who chartered her own course and who left in her wake a confused cry of confusion, admiration, angst, and uncertainty, when there were attempts to define the deeper impulses behind Pettit’s work in the mountains

Thus, the impulse behind Katherine Pettit’s work in the mountains appears to have been a multistranded blend drawn from a variety of sources: her own intelligence and personal dynamism; the evangelical and social concern of the Presbyterian church — probably as mediated by Guerrant; some recurrent themes in certain popular fiction of the day; the liberal social concern of the WCTU and the Federation of Women’s Clubs; the progressive social work undertaken by other women at the time (especially the Breckinridges); and the example of settlement work in northern cities, into which a few of her Bluegrass friends were being drawn.

Whisnant, here, seems to prefer to cast Pettit into the role of a confused contrarian copyist rather than an inspired and motivated leader whose broad universe was comprised of sampling first-hand the world around her and doing that with sensitivity to all classes, sexes, and methodologies. She was certainly a shape-shifter and knew how to forge a wealth of relationships and results, but one trait she does not reveal easily, if it existed, is weakness. It is all too easy to make a myth of Pettit, and, even in this essay, too unjust.

In truth and fairness to Whisnant, the image of a “multistranded blend” captures Pettit but without giving credit to her amazing ability to synthesize and build new ideas to fit the times and the environment of the Central Appalachians. She was adaptive. Few of the many observations put forward by Whisnant stand out as either dominant or defining of Pettit, as is often the case in complex, adaptive, and focused folk. Regarding the Guerrant influences, (Rev. Edward Owings Guerrant was the founder of the Soul Winners Society and is often seen as the founder of the Home Missions movement in eastern Kentucky. Guerrant was a close family friend and was known throughout the Central Appalachians for his persistent service to the region. [See: Mark Andrew Huddle, Ohio Valley History, Filson Historical Society and Cincinnati Museum Center, Vol. 5, No. 4, Winter 2005, for an overview of Guerrant’s contributions to the Central Appalachians.]

Pettit’s impulses were also pervasive traits in the cohort that started Hindman and in many women who followed Pettit and de Long to Harlan County and to other early settlement schools. While many of the women in the rural settlement movement were as smart and forward-looking as Pettit and well aware of their social common bonds, few were as brave as Pettit. The friendships were often sincere and deep, and cooperative between Pine Mountain and Hindman, as shown by the correspondence following Pettit’s departure. The forward-looking women, the early founders of Hindman and of Pine Mountain Settlement School, and particularly Katherine Pettit, are not footnotes but are as fundamental to the region’s growth and development as is its coal.

An entry in Notable American Women, 1607 – 1950: A Biographical Dictionary (p. 57) describes Miss Pettit as having a “strong face [that] revealed her personality; a firm planner and manager, yet outgoing, patient, and kind. She was beloved by children and overworked mothers for her suggestions and personal advice….” Some who worked under her direction were, however, often less kind, finding her work ethic and manner bruising in their demands on the often delicate expectations of newcomers to the mountains. Pettit was a sharp observer. A newcomer to the school at Pine Mountain described her as an “observer” — always on the periphery — watching and listening and learning.

11_2470 Miss Katherine Pettit (in hat and white) and others. [098_IX_students_11_2470_001.jpg]

The late 1930s and Retirement, Farm Advisor, Travel

Katherine Pettit served as co-director at Pine Mountain Settlement School until her retirement in early 1930. Following her retirement, she often traveled throughout Harlan County and neighboring counties, urging farmers to adopt modern farming techniques. She punctuated her farming consultation with personal travel and short substitutions for staff at the School and the School’s extension settlements, particularly Line Fork. A solo trip to South America in 1932 was an adventure that not even Pettit could have imagined and that opened her universe even wider at the end of her life.

In the early Fall (September?) of 1930, Pettit contacted her former colleague at Hindman, Ruth Huntington (1875-1940), and departed for a lengthy stay in Carmel-by-the-Sea, on the coast of Northern California, with Ruth. Her California friend had spent her earliest years at Hindman with Pettit, hired by May Stone to be the Principal of the new so-called W.C.T.U. (Women’s Christian Temperance Union) School. Ruth’s architectural suggestions were frequently sought by Pine Mountain and also Berea and resulted in the “Practice House” models found at Hindman, Pine Mountain, and Berea College.

Following her departure from Hindman in 1919, Ruth worked as an educator and Principal at several schools, including a girls’ school in Puerto Rico, where she joined Mary Rockwell Hook’s sister and another schoolmate. She also worked for a brief time in Hawaii. Ruth, a 1897 graduate of Smith College, had served in the position of Principal at Hindman but also assisted May Stone with the management of the school and later served on the Executive Council of the Settlement School. When she went to California, Ruth attended Berkeley and took additional courses in education and worked for a time with the California Junior Republic, helping them establish a weaving program before settling in Carmel in 1922 as Principal of the local grade school in Carmel.

Both Katherine and Ruth were large and strong women, and both loved gardening and unique houses. Ruth and Katherine also shared a deep interest in craft and especially weaving. Ruth’s interest in architecture and design led her to build her home in Carmel, close to the unique and famous dwelling of the poet Robinson Jeffers and his wife Una. In his poem “Carmel Point,” Jeffers laments the growing suburban population in Carmel and how the ocean town was being defaced with each new arrival. He says of the change on “it” (Carmel)

… Now the spoiler has come: does it care?

Not faintly. It has all time. It knows the people are a tide

That swells and in time will ebb , and all

Their works dissolve. …We must uncenter our minds from ourselves;

We must unhumanize our views a little, and become confident

As the rock and ocean that we were made from.

— Robinson Jeffers, Selected Poems, Vintage Books 1965.

While Carmel-by-the-Sea was in the process of becoming a mecca for writers and artists, and so-called “bohemians,” there is no evidence that Ruth adopted the lifestyle of her neighbors. Yet, the early intellectual climate must have had an appeal to Ruth and also to Pettit. By all accounts. Pettit stayed with Ruth Huntington until December of 1930, when she “uncentered her mind” and the tides took hold, and she continued the travel adventures she had begun in 1928.

Following Pettit’s death in 1936, Ruth Huntington’s life took a darker turn, and in 1940 she and her small dog leaped from the Carmel cliffs into the ocean, returning to the “rocks and ocean we were made from.”

1932 Travels and High Adventure

Katherine Pettit’s appetite for high adventure and travel was pulled by the tides when, in 1928, she took time away from her responsibilities at PMSS to arrange for a world cruise. The trip she arranged was for a boat trip that was to be an “around the world” trip. As she traveled in the comfort of an ocean cruise liner, she visited many ports of call and friends along the way. It was the beginning of a lifelong love of travel. And dramatically removed from the close life in the Kentucky mountains. Aunt Sal once said to Pettit that she, Pettit, had sailed around the world, but that she, Sal, could spin — referring to the difficult task of spinning wool. It is difficult to know who in that conversation came closest to “unhumanizing their views” as both spoke and lived with such deep conviction and purpose.

Just three years following her departure from Pine Mountain, in 1931, at the age of 64, and retirement from Pine Mountain, Pettit struck out once again to see the world. She was now on her own time and responsible only for herself. She was, as usual, intentional in her desire to explore Mexico, Central, and South America and to especially investigate native weaving in those countries. On this trip, she traveled by freighter, not in the comfort of a passenger liner. This trip was deliberately not planned as an ordinary tourist journey. It was her journey — alone, on an unconventional transport, and on an itinerary that defied the common tourist destinations. Her journey was certainly not one for the faint of heart — it was never intended to be.

A year later, on her return trip on the SS Montevideo Maru in February of 1932, she wrote a long letter to her California friend, Ruth Huntington about her adventures. The following excerpts describe something of her joy, her trials, her incidents, accidents, and friends made along the way. The long letter, in the Berea College archive describes the journey, but even more, we learn considerably more about the inner Pettit — the woman:

When first [ more I] said that I was going to South America, many said that no woman could go alone, especially if she did not know the language. By the time I had my passport and visas [from consulates in Los Angeles], I began to wonder. ..[now] …I’ve learned the difference between a tourist and a traveller [sic]. The traveller has some notion of what he is going to see; the tourist has not. We see only what we are prepared to see.

… you told me to beware of revolutions, and I told you that I would not let them keep me from going to places. I surely did not know what a revolution was when I said that. I did get to Cuzco [Peru] over the new bridges that were guarded by machine guns, even if the revolution in Peru was not over, and I had to run from the bullets after I got there. I was held up by the Chilean revolution: ran from the machine guns in Asuncion where I was arrested. When asked what I was doing on the street when a revolution was on, I said I wanted to see if the Paraguan [sic] revolution was like the Chilean and Peruvian ones. Now I know. … [Berea College Special Collections, Katherine Pettit Papers, ]

Following her instincts for locating good weaving, she sought out pre-Incan textiles in the Lima Museum in Peru [probably the National Museum of Archaeology, Anthropology and History of Peru], the oldest museum in the country. After viewing some of the early Incan textiles, she commented on their density of some “100 to 160 threads to the inch.” She noted that the Incan natives were

… said to be the most industrious in the world. As they attend their flocks, they are always running, spinning as they run, with the baby and another bundle of produce on their backs, dressed in colored wool homespun.

While she had no Spanish, she negotiated the purchase of a vicuna rug for a fraction of its worth — always the savvy collector of weavings. She never abandoned her love of indigenous craft and particularly the craft of weavings of high quality. Many of the photos in the PMSS Fireside Album titled, “WEAVING”, most likely were donated by Pettit.

End of Life and Health Issues

At 64, Pettit was hearty but not as hearty as she imagined. Plagued by increasing weight gain and growing mobility issues she took a fall in Santiago and broke a wrist, and then another fall which broke her ribs. The incidents slowed her down, but she continued through earthquakes, the continuing revolutions in Santiago, Chile, and the perpetual tea parties of friends she made and met along the way. In the tropical forests of Brazil, she was again the “Blossom Lady” where she saved and replanted native orchids that had been plundered by orchid thieves who were selling the plants to merchants across the world.

Ever the champion of the land and the people, she wrote to Ruth Huntington again, that on her last morning in Rio de Janeiro, she was heartened to know that a Brazilian woman had donated some 1200 acres of land for the Protestant Mission in Rio. The mission school was to serve as a “farm school” where the street children of Rio might find a new beginning. These and more stories of the southern continent that she relayed to her friend Ruth must have sounded familiar to Ruth and no doubt stirred memories of their earlier shared time at Hindman in the lush mountains of Kentucky and the hours the two of them spent attending to Ruth’s coastal garden.

Health, Independence, and the Loss of Friend Ruth Huntington

Pettit remained in contact with her California friend, Ruth Huntington until the end of her life. Pettit, with her death in 1936, was spared the tragedy of her long-standing friend’s suicide. In 1940, Huntington took her life by leaping from the cliffs into the sea at Carmel. It has been suggested that Huntington was in poor health, and that may have prompted her suicide. Poor health was anathema to both Pettit and Huntington. But poor health plagued both women at the end of their lives and limited their mobility.

The influence of Huntington on the career of Pettit and their deep friendship begs further exploration, particularly the influence of Huntington on the educational values and ideas of Pettit. Certainly, the two had strong views on education and sorting out those influences could shed more light on both the Hindman and the Pine Mountain Settlement schools’ educational experiments. The influence of Pettit on the career and life of educator Huntington during her years at Hindman and during their life-long friendship following Huntington’s return to the West Coast could shed more light on the strongly held educational values of both women. Comparing the educational work of Huntington in Carmel as a much-honored educator and school principal in Carmel, with the educational ethos of Pettit may shed light on the many successes — and failures of both women. Letters between the two friends are scattered among many institutions, and if joined, might shed more light on the lives of these two strongly independent and influential women.

Death of Pettit

Pettit died of cancer in 1936, but not before receiving some of Kentucky’s highest honors. On her return to Kentucky in late 1932, Pettit was awarded the Algernon Sydney Sullivan Medallion by the University of Kentucky as an outstanding citizen of Kentucky. The award, created to recognize and to “…perpetuate the excellence of character and humanitarian service” of the individual, must have been heartening to Pettit, who was honored in the company of some of the South’s most important scholars and civic humanitarians. Lauding the “ideals of heart, mind, and conduct as evincing a spirit of love for and helpfulness to other men and women,” the award was testimony to the lifetime Pettit gave to the southern Appalachians and their people. She lived only a short four years more after receiving the award. Her friend Mary Breckenridge of the Frontier Nursing Service received the honor in 1935, and the author and friend Frances Jewell McVey, who had written of Pettit’s accomplishments in the often-cited “The Blossom Woman,” was awarded the same honor in 1938.

Frances Jewell McVey, wife of the University of Kentucky President, Frank LeRond McVey, and a graduate of Vasser College and Columbia University, had stayed a steady friend to Katherine Pettit and many of those in the early Berea group to Harlan County, led by Frost. That was a journey that first introduced Pettit to the eastern Kentucky people and mountains. It was so fitting that McVey, another trail-blazer was present at the beginning of Pettit’s Harlan County adventures and there at their end. [See: 1934 Blossom Woman by Florence McVey [McVey, Frances Jewell. “The Blossom Woman.” Mountain Life & Work. 10 (April 1934): 4, 5. Print. [Also: Appalachian Heritage. 1975, Vol 3 (4) pp. 62-74.]

KATHRINE PETTIT AND EMMA LUCY BRAUN

In the short four years before her death, Katherine Pettit, along with Emma Lucy Braun, the well-known Cincinnati biologist and author of The Deciduous Forests of Eastern North America, spoke for the old-growth forests of Eastern Kentucky and the land that Pettit and Braun had come to love by walking many of the forest floors together. In a talk entitled “Let Us Work Together to Save This Area,” Pettit and Braun raised awareness of the threat to the primeval forests of both Kentucky and Ohio. Shortly after their talks and promotional tours, they founded Save Kentucky’s Primeval Forests League, designed to protect the original deciduous forests of southeastern Kentucky. While they were not successful in saving the targeted forest and giant poplars of what is now Lilly Cornett Woods Appalachian Ecological Research Park, they undoubtedly raised public attention to the plight of other old-growth forests.

Katherine Rebecca Pettit died in Lexington of cancer on September 3, 1936, at the age of sixty-eight and was buried in Lexington Cemetery along with other members of her family. A memorial plaque placed on the Pine Mountain Settlement School Chapel wall, sums up her life’s work:

Katherine Pettit, 1869-1936, pioneer and trail-breaker. Forty years she spent creating opportunity for mountain children here and elsewhere. In life, she ever refused praise. In death, she is too great for it.

Katherine Pettit holding a map of South America. [pmss0003.jpg]

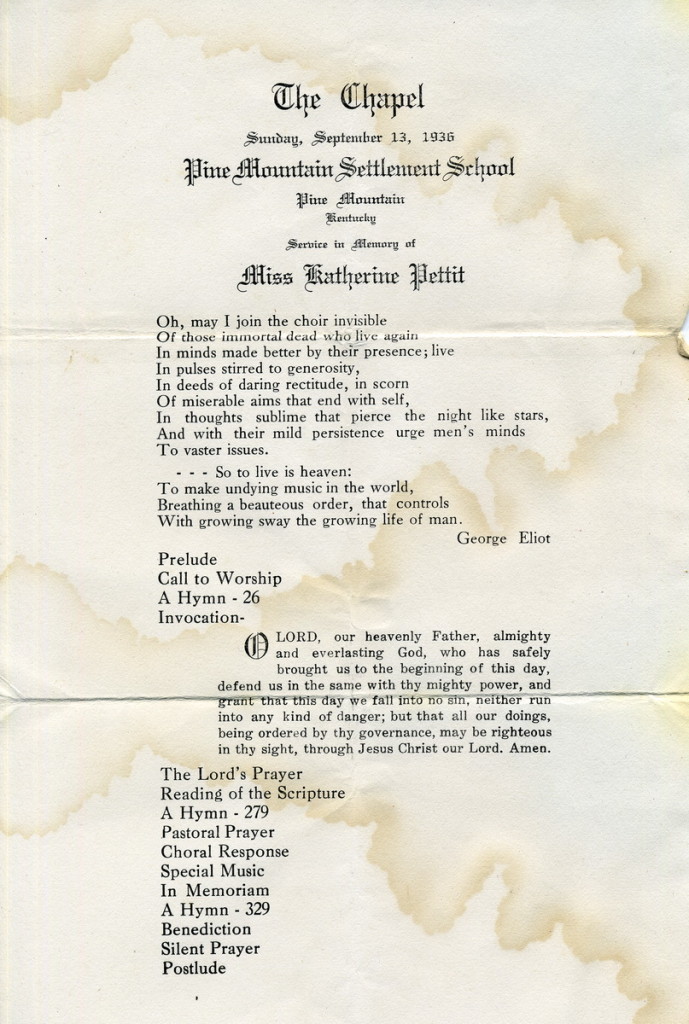

SERVICE IN MEMORY OF KATHERINE PETTIT, September 13, 1936

Shortly after Katherine Pettit’s death, Ruth B. Gaines, who worked with Pettit as a housemother during the early years of the School and who later worked at John C. Campbell Folk School, wrote to Glyn Morris, then Director of Pine Mountain:

Thank you for the copy of the service and the prayer in memory of Miss Pettit. I think the prayer is a very beautiful one and I know Miss Pettit would appreciate it and give you her lovely smile. She was a rare character and will be missed by many more than we know.

Angela Melville, a staff member who often assisted with administrative duties at Pine Mountain, kept in touch with Pettit when she left the School. When Pettit died she asked the current director, Glyn Morris, what hymns were chosen for the service of Pettit at the School. Morris replied:

The hymns were “Father Again, in Jesus’ Name we Meet,” words by Lucy E. G Whitmore, “O Love Divine That Stooped to Share” by Oliver Wendell Holmes, and the last hymn, I am sorry to say, was not the one which intended. The printer made a mistake and printed 329 which is “Lord, Speak to me that I May Speak.” It should have been “For All the Saints Who From Their Labors Rest.” Unfortunately, I did not check the program, but the hymn fitted in very nicely with the service, even so. …“

Angela Melville Correspondence, October 6, 1936.

SEE ALSO:

DIRECTORS GUIDE

ALICE COBB STORIES Line Fork Community Remembers Miss Pettit 1936

ALICE COBB STORIES Told by Miss Pettit [See also: PLANNING for PMSS]

DARWIN D. MARTIN 1927 Correspondence Part 1

DARWIN D. MARTIN 1927 Correspondence Part 2

FARM Agricultural Correspondence 1917-1918

FARM Agricultural Correspondence 1919-1920

HELEN WILMER STONE VINER Staff Biography

KATHERINE PETTIT Book Collection

KATHERINE PETTIT Commonplace Book Copies of Selected Pages at PMSS

(Original held by Transylvania University Special Collections)

KATHERINE PETTIT Correspondence Guide 1911-1936

KATHERINE PETTIT Correspondence 1911 My Dear Friends Letter….

KATHERINE PETTIT Image Inventory of Woven Coverlets collected by Pettit

The full undated inventory of woven coverlets collected by Kate Pettit is held by University of Kentucky [Box 12, folder 13]. She presented these coverlets to the John Bradford Society in 1936. They currently (1986) are in the Bodley-Bullock House, 200 Market Street, Lexington, Kentucky. Photo negatives of the coverlets are included in the audio-visual series at the University of Kentucky Archive and Research Center.

KATHERINE PETTIT Photograph Album

KATHERINE PETTIT Social Settlement in KY Mountains Sassafras Album 1901

KATHERINE PETTIT Weaving at PMSS Beginnings

KATHERINE PETTIT WRITING 1899-1900 Camp Cedar Grove Report

KATHERINE PETTIT WRITING 1921 Story of Andy

KATHERINE PETTIT WRITING Larnin’ on Greasy [n.d.]

LEWIS LYTTLE Letters to Katherine Pettit 1911

LEWIS LYTTLE Letters to Pettit and Nolan 1912

NOTES – 1936 – Katherine Pettit. “Pioneer Mountain Worker”

NOTES – 1999 – Katherine Pettit, 1869-1936

NOTES – 2013 – “Pine Mountain Beginnings” by James S. Greene III, pp. 8-14

NOTES – 2019 – Winter, pp. 4-5

PUBLICATIONS RELATED 1942 Katherine Pettit

A Memory and an Appreciation by Mary Beech

KATHERINE PETTIT 1936 MEMORIAL SCRAPBOOK

PUBLICATIONS RELATED

1934 Blossom Woman by Frances McVey [McVey, Frances Jewell. “The Blossom Woman.” Mountain Life & Work. 10 (April 1934): 4, 5. Print.

[Also: Appalachian Heritage. 1975, Vol 3 (4) pp. 62-74.]

Related:

EMMA LUCY BRAUN Visitor

PLANNING for PMSS

GALLERY: Katherine Pettit

To use the colloquial phrase, the photographs of Katherine Pettit, the woman, “are as scarce as hen’s teeth.” She resisted all attempts to include herself in photographs and but a few have surfaced over the years in addition to the few “official” ones that are often found with her biography. In one instance, she appears to have vigorously scratched out her image in a photograph that was apparently taken without her permission.

Click on image for full view.

- Jack’s Gap. Katherine Pettit (older woman with hat to left of image) and Ethel de Long (back against pine tree) and children at Jack’s Gap, above PMSS. [X_099_workers_2524a_mod.jpg]

- PMSS workers (from left): Katherine Pettit; Ethel de Long; Wilmer Stone; (?); Ruth Hench; Dr. Grace Huse; (?); Evelyn Wells; (?); Marguerite Butler; Luigi Zande. [X_099_workers_2489c_mod.jpg]

- Katherine Pettit at Big Log. [kingman_046b.jpg]

- Katherine Pettit at Big Log. [kingman_046a.jpg]

- 11_2470 Miss Katherine Pettit (in hat and white) and others. [098_IX_students_11_2470_001.jpg]

- Woman {Pettit ?] on horseback on trail. Katherine Pettit Album I.

- “Fair Day, September 1929. Marian [Kingman], Miss Pettit [Katherine Pettit], Harriet [Crutchfield], Miss [Ruth] Gaines. [?] Morrison, Brit Wilder. [kingman_084a.jpg]

- Katherine Pettit at Big Log, 1929. [kingman_078]

- Frances Lavender Album. Fair Day. Sept. 1918. “First picture ever caught of K[atherine] Pettit. [standing in background, center*]. 1. Duncan Foster, teacher; 2. H. Babsen, Housemother; 3. Miss Benedict, kitchen; 4. P. Peck, my room-mate; 5. A Mt. woman; 6. Miss [Katherine] Pettit; 7. Mrs. Holton, a teacher; 8. A Mt. woman (Mrs. Day); Mrs. Zande is in the background sitting on a table with head down, knitting.” *Pettit[?], seated with hat.”[lave026.jpg]

- pettit_1913_020.jpg

- Far left. Miss Katherine Pettit [?] and two women hiking. X_099_workers_2527x_mod.jpg

- PMSS workers (from left): Katherine Pettit ; Ethel de Long ; Wilmer Stone ; ? ; Ruth Hench ; Dr. Grace Huse ; (?) ; Evelyn Wells ; (?) Marguerite Butler ; Luigi Zande. X_099_workers_2489.jpg

- Pettit [scratched out with pen] Cabin with woman and three children at well. Figure of woman has been scratched out next to well. (Miss Pettit ?) Cabin lacks complete chimney. X_099_workers_2494d_mod.jpg

- Miss Katherine Pettit [?] seated at desk in Old Log, c. 1913-14, X_099_workers_2526b_mod.jpg

- Miss Katherine Pettit, seated on horse with man and woman standing nearby on road below Indian Cliff dwelling at School entrance. X_099_workers_2494_mod.jpg

- Summer camp at Sassafras, KY, 1901. Katherine Pettit Sassafras Album. [sas_002.jpg]

| Title | Katherine Pettit |

| Alt. Title | Katherine Rebecca Pettit ; Katherine Rhoda(?) Pettit ; Kate Pettit ; |

| Identifier | https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=424 |

| Creator | Pine Mountain Settlement School, Pine Mountain, KY |

| Alt. Creator | Ann Angel Eberhardt ; Helen Hayes Wykle ; |

| Subject Keyword | Katherine Pettit ; Katherine Rebecca Pettit ; Katherine Rhoda Pettit ; Pine Mountain Settlement School ; directors ; education ; Progressives ; rural education ; community health ; Appalachian folklore ; administration ; Appalachian music ; Appalachian dance ; botany ; architecture ; Sayre School ; WCTU ; State Federation of Women’s Clubs ; Jane Addams ; Ellen Gates Starr ; Hull House ; May Stone ; Wellesley College ; Camp Cedar Grove ; Camp Industrial ; Sassafras Social Settlement ; WCTU Settlement School ; Hindman Settlement School ; William Creech Sr ; Ethel de Long Zande ; Smith College : Mary Rockwell Hook ; Ruth Huntington ; Wilmer Stone Viner ; Sullivan Medallion ; E. Lucy Braun ; Chapel ; natural dyes ; weaving ; Appalachian crafts ; Pine Mountain, KY ; Harlan County, KY ; Hindman, KY ; Wellesley, MA ; Lexington, KY ; Louisville, KY ; Fayette County, KY ; Knott County, KY ; Perry County, KY ; Sassafras, KY ; Hazard, KY ; New Jersey ; Paris, France ; Saluda, NC ; South American ; Cincinnati, OH ; Southeastern Kentucky ; Pine Mountain Notes ; Mountain Life & Work ; Berea (KY) College ; |

| Subject LCSH | Pettit, Katherine Rebecca, — 1868 – 1936. Educators — Biography. Women — Social Reformers — Southern States — History. Pine Mountain Settlement School (Pine Mountain, Ky.) — History. Education –Kentucky –Harlan County. Rural schools — Kentucky — History. Schools — Appalachian Region. Rural schools — Appalachian Region, Southern. |

| Date digital | 2004-06-28 ; 2013-10-03 ; 2015-12-01 |

| Publisher | Pine Mountain Settlement School, Pine Mountain, KY |

| Contributor | n/a |

| Type | Text ; image ; |

| Format | Original and copies of documents and correspondence in folders in filing cabinet ; photograph album(s) ; books ; clipping files ; |

| Source |

Series 04: ADMINISTRATION ; Series 09: BIOGRAPHY |

| Language | English |

| Relation | Is related to: Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections, Series 04: ADMINISTRATION ; Series 09: BIOGRAPHY ; PLANNING for PMSS |

| Coverage Temporal | 1868 – 1936 |

| Coverage Spatial | Pine Mountain, KY ; Harlan County, KY ; Hindman, KY ; Wellesley, MA ; Lexington, KY ; Louisville, KY ; Fayette County, KY ; Knott County, KY ; Perry County, KY ; Sassafras, KY ; Hazard, KY ; New Jersey ; Paris, France ; Saluda, NC ; South American ; Cincinnati, OH ; Southeastern Kentucky ; Berea, KY ; |

| Rights | Any display, publication, or public use must credit the Pine Mountain Settlement School, Pine Mountain, KY. Copyright retained by the creators of certain items in the collection, or their descendants, as stipulated by United States copyright law. |

| Donor | n/a |

| Description | Core documents, correspondence, writings, and administrative papers created by or addressed to Katherine Pettit ; clippings, photographs, publications by or about Katherine Pettit ; |

| Acquisition | n/d |

| Citation | “[Identification of Item],” [Collection Name] [Series Number, if applicable]. Pine Mountain Settlement School Institutional Papers. Pine Mountain Settlement School, Pine Mountain, KY. |

| Processed by | Helen Hayes Wykle ; Ann Angel Eberhardt ; |

| Last updated | 2001-05-28 hhw ; 2007-07-10 hhw ; 2009-09-13 aae ; 2013-09-10 hhw ; 2015-11-06 hhw ; 2015-12-01 hhw ; 2018-08-25 hhw ; 2020-12-12 hhw ; 2021-06-27 hhw ; 2021-11-25 hhw ; 202203-17 aae ; 2022-08-16 hhw ; 2024-07-17 hhw ; 2024-08-25 aae ; 2025-06-29 aae ; |

| Bibliography |

Written By Katherine Pettit “Stories Told by Miss Pettit,” in PLANNING For PMSS. Pine Mountain Settlement School Institutional Papers. Pine Mountain Settlement School, Pine Mountain, KY. Pettit, Katherine. Commonplace Book [Scrapbook]. n.d. Unpublished scrapbook. Original held by the University of Kentucky, Special Collections. Pettit, Katherine. An Appeal for Books for the Kentucky Mountains. Outlook (1893-1924) July 13, 1901, Vol. 68 (11), p.650. Books about or including Katherine Pettit Alvic, Philis. Weavers of the Southern Highlands. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 2003. Print. Appleton, Thomas H., Angela Boswell, editors. Searching for Their Places: Women in the South Across Four Centuries. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2003. Print. Day, Carrie. The Love They Gave: A Tribute to Miss Katherine Pettit and Miss Ethel Delong, Founders of Pine Mountain Settlement School, Pine Mountain, Harlan County, Kentucky. Big Creek, KY: Carrie Day, 1982. Print. Day, Douglas. In the World of My Ancestors: The Olive Dame Campbell Collection of Appalachian Folk Song. 1908-1916. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 1994: “In 1908, Olive Dame Campbell, young bride of John C. Campbell, the new Director of the Southern Highlands Division of the Russell Sage Foundation, accompanied her husband on his pioneering social survey of the Southern Appalachian mountains. She began almost immediately to collect ballads and folksongs she heard in the course of her travels. By 1916, her collection, unusual in the attention she paid to collecting tunes as well as song texts, had attracted the attention of her benefactors at the Sage Foundation, Harvard ballad scholar George Lyman Kittredge, and British folksong collector Cecil Sharp. In 1917, Campbell and Sharp together published the pivotal English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, which contained some forty-four of sixty-odd songs collected by Mrs. Campbell. The work has been accepted into the canon of American folksong scholarship. The author, working as a public folklorist at the John C. Campbell Folk School eighty years after Mrs. Campbell began her collection, found that the only existing copy of Mrs. Campbell’s manuscript was a carbon copy in the Ralph Vaughn Williams Memorial Library at Cecil Sharp House in London. Examination of the manuscript revealed that the collection consisted of not only the known sixty songs (with over twenty unpublished tunes) but the texts to one hundred and sixty other folksongs collected in the mountains of Georgia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and North Carolina. Marginalia on the manuscript, when correlated with correspondence in the Campbell Papers in the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, showed that Mrs. Campbell’s collection was, in fact, a collaboration with other members of the Council of Southern Mountain Workers, especially Katherine Pettit of the Hindman Settlement School and Isabel Rawn of the Martha Berry School, neither of whom were credited in either the 1917 or the 1932 edition of EFSSA. A full reappraisal of the collection sheds new light on the cultural intervention of the self-styled “folk movement in the mountains” in the first decades of the Twentieth Century.” Greene, James. Progressives in the Kentucky Mountains: The Formative Years of the Pine Mountain Settlement School, 1913-1930. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing. 1982: [“This is a study of the creation and early development of a private, progressively-oriented educational institution in Southern Appalachia (Harlan County, Kentucky) in the early years of this century at a time when Appalachian society was in transition from a rural to an industrialized lifestyle. Based largely upon school archives and oral history, the study consists of three parts: first, a look at events surrounding the founding of the school; second, a detailed analysis of its curriculum and the make-up of its student body and staff at the time; third, an examination of the school’s functioning as a social settlement. Its founders, Katherine Pettit, and Ethel de Long Zande, were in many ways textbook progressives. Like Jane Addams and John Dewey, they saw education as a force for social reform and wanted the child to become an instrument in the creation of a new mountain society drawing upon the best of the old and the new in mountain life. They saw education as a process of growth through living a meaningful life at any point in one’s existence. The duty of the school was to provide the student with an idealized environment in which such growth could occur, a growth formative of character which would sustain him throughout life. Thus Pine Mountain organized its boarding program around cottages rather than dormitories; its students participated in a work program in which each job was important to the well-being of the school community; and it fostered spiritual and cultural values through a low-key Christian emphasis and through the preservation and revival of mountain crafts, ballads, and folk dancing. With regard to the community, the school attempted to mediate between the traditional culture and the outside world, assisting neighbors in health, recreation, religious, and economic development.” — Greene] Heinemann, Sue. Timelines of American Women’s History. New York: Berkley Publishing Group, 1996. Print. James, Edward T., Janet Wilson James, and Paul S. Boyd. Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary. Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1971. Print. Johnson, Joan Marie. Southern Women at the Seven Sister Colleges: Feminist Values and Social Activism 1875 – 1915. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2008. Print. Kleber, John E. The Kentucky Encyclopedia. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1992 (2nd printing). Katherine Pettit’s entry was written by Nancy Forderhase. Print. Pettit, Katherine. “Ballads and Rhymes from Kentucky,” Journal of American Folklore. (1907). “The first real attempt to publish some of the old songs Kentuckians had been singing for over a hundred years,” according to Charles K. Wolfe in his book, Kentucky Country: Folk and Country Music of Kentucky. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1982. Print. “Some Remarkable Kentucky Americans.” Outlook (1893-1924), Feb. 21, 1917, p.310. [Discusses racial and ethnic mix of rural Eastern Kentucky and Katherine Pettit’s new Pine Mountain Settlement School.] Stoddart, Jess, editor, Katherine Pettit, and May Stone. The Quare Women’s Journals: May Stone & Katherine Pettit’s Summers in the Kentucky Mountains and the Founding of the Hindman Settlement School. Ashland, KY: Jesse Stuart Foundation, 1997. Print. Viner, Wilmer Stone, H.E. Scrope Viner, and Katherine Pettit. The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. Saluda, NC: Excelsior Printers, 1946. Print. Whisnant, David E. All That is Native and Fine: The Politics of Culture in an American Region. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 1983. Print. Wolfe, Charles K. Kentucky Country: Folk and Country Music of Kentucky. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1996. Print. Other Sources About Katherine Pettit. For early Pettit family resources: The Pettit Research Project “Ballads and Rhymes From Kentucky,” in Appalachian Heritage, 1974, Vol. 2(1), pp. 19-26. Beech, Mary, “Katherine Pettit A Memory and Appreciation, 1942, Lincoln Herald, Vol. XLIV no.1, p.10. Blackwell, Deborah. “The ability ‘to do much larger work’: Gender and reform in Appalachia, 1890-1935. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. 1998: “This dissertation seeks to address two broad categories of inquiry concerning women’s reform efforts in Appalachia at the turn of the twentieth century. The first purpose is to tell the stories of five women and their struggles to change the lives of mountain residents in a period of rapid change. The women considered herein include May Stone of Hindman Settlement School, Katherine Pettit of Hindman and Pine Mountain Settlement Schools, Eleanor Marsh Frost of Berea College, Olive Dame Campbell of the John C. Campbell Folk School, and Mary Breckinridge of the Frontier Nursing Service. The second and more ambitious goal is to begin to understand the impact of gendered perceptions on the creation of Progressive-era reform. The women profiled in this study all brought gender-based notions of the world to bear on their work as they shaped Appalachian progressivism. Pettit, Stone, Frost, Campbell, and Breckinridge exhibited specific, middle-class notions of women’s place in society, and their organizations reinforced those views. Women reformers have often been understood either as victimizers of mountain people or as selfless angels. The truth, however, is considerably more complex. This study suggests that Appalachia’s women reformers negotiated space between traditional gender roles and modern ideas about science and learning in the process of creating reform. Through their organizations, these five women attempted to ameliorate the poverty and illiteracy faced by many mountain residents. In the process, they embraced modern methods of mothering and housekeeping as they reinforced those traditional female duties. By promoting craftwork as a source of income for families, these female reformers acknowledged the importance of women to the household economy. Their public health work addressed critical needs and reflected the maternalist stress on knowledgeable motherhood. Their relationships with the state and other authority figures, however, moved beyond lobbying for mothers to address good roads and licensing nurse-midwives. In creating reform efforts, these women relied on networks of kinfolk, friends, and colleagues to sustain and inspire them at a time when their work was often perceived as daring and risky. Applying gender analysis to Appalachian reform thus results in a complex portrait of control and benevolence.”] Durisek, Susan Smith. “A coat of ferns: the plants add a lushness to gardens.” In the “Living” section of online Kentucky.com, Lexington Herald-Leader (accessed 2009-09-09). Internet resource. England, Rhonda George. Bringing Modern Notions of Childhood and Motherhood to Preindustrial Appalachia: Katherine Pettit and May Stone, 1899-1901. [Paper presented at the Appalachian Studies Conference in Morgantown, WV, on March 17-19, 1989.] Journal of the Appalachian Studies Association, 1 January 1990, Vol. 2. pp.69-75. Print. Engelhardt, Elizabeth. Southern Appalachian Ecological Literature and Feminism: Women Authors Address the Land, 1890-1910. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses. England, Rhonda George. Voices from the History of Teaching: Katherine Pettit, May Stone, and Elizabeth Watts at Hindman Settlement School, 1899-1956. Thesis, 1990. Print. Farr, Sidney Saylor. The Quare Women’s Journals: May Stone & Katherine Pettit’s Summers in the Kentucky Mountains and the Founding of the Hindman Settlement School, and: Courageous Paths: Stories of Nine Appalachian Women (review) NWSA Journal, 1999. Vol. 11(3), pp. 205-207. Print Foderhase, Nancy. {Book Review} The Quare Women’s Journals: May Stone and Katherine Pettit’s Summer in the Kentucky Mountains and the Founding of the Hindman Settlement School. The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, 1 October 1997, Vol 95(4), pp.433-435. Print. Furman, Lucy. “Katherine Pettit, Pioneer Mountain Worker.” Notes from the Pine Mountain Settlement School. 8 (November 1936). Print. Glen, John M. [Book Review] The Quare Women’s Journals: May Stone & Katherine Pettit’s Summers in the Kentucky Mountains and the Founding of the Hindman Settlement School. The Georgia Historical Quarterly, 1 July 1998, Vol 82(2), pp.451-452. Lockwood, Carol A. (editor) 2000. American National Biography Online. FULL TEXT. McEntee, Grace. [Book Review] The Quare Women’s Journals: May Stone & Katherine Pettit’s Summers in the Kentucky Mountains and the Founding of the Hindman Settlement School, Appalachian Journal, 1 October 1998, Vol 26(1), pp.54-57. McVey, Frances Jewell. “The Blossom Woman.” Mountain Life & Work. 10 (April 1934): 4, 5. Print. [Also: Appalachian Heritage. 1975, Vol 3 (4) pp. 62-74.] Archival Sources Neville, Linda (1873-1961). Linda Neville papers, 1783-1974. Includes Charles Kerr (1863-1950); Nevile family (1783), Special Collections Research Center, Special Collection, and other locations. The Bullock-Pettit Photographic Collection, Bullock, Dr. Waller Overton, 1875-1953. Bodley-Bullock House (Lexington, Ky.); Bullock, Waller O. (Waller Overton), 1875-1953; Bullock, Minnie Pettit, 1877-1970; Ephraim McDowell House (Danville, Ky.); Hindman Settlement School (Hindman, Ky.); Historic buildings–Kentucky–Conservation and restoration; Pettit, Katherine Rebecca, 1869-1936; Pine Mountain Settlement School (Pine Mountain, Ky.); Transylvania University (Lexington, Ky.). The Bullock-Pettit Photographic Collection, .5 cu. ft. (2 boxes): 100 images. University of Kentucky.

Additional papers of Katherine Pettit are located in the following collections: Hutchins Library Special Collections, Berea (KY) College “Find A Grave Index,” database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:QVLN-6VYJ : 26 August 2018), Benjamin F. Pettit; Burial, Lexington, Fayette, Kentucky, United States of America, Lexington Cemetery; citing record ID 97959222, Find a Grave, http://www.findagrave.com. “United States Census, 1880,” database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MCCF-QQ6 : 26 August 2018), Benjamine Pettit, East Hickman Magisterial District, Fayette, Kentucky, United States; citing enumeration district ED 63, sheet 232D, NARA microfilm publication T9 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.), roll 0412; FHL microfilm 1,254,412. |

Return To:

DIRECTORS Guide

BIOGRAPHY – A-Z