Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 10: BUILT ENVIRONMENT

Series 12: LAND USE

Land Use Plan for Pine Mountain

Mid-1930s

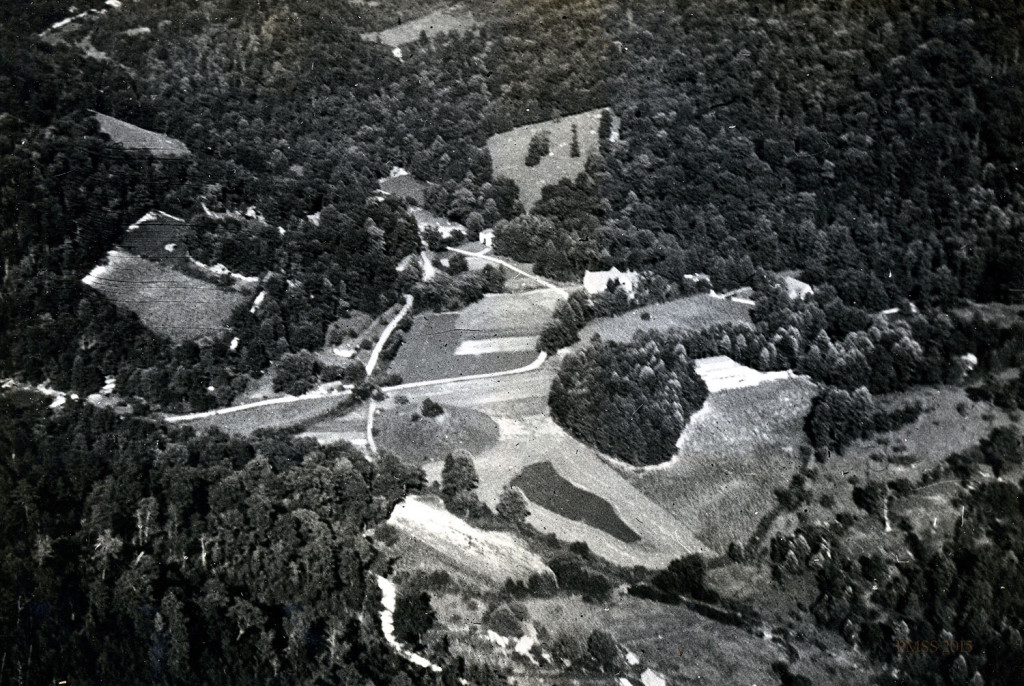

Aerial view of Pine Mountain Settlement School, c. mid-1930s. Arthur W. Dodd Album. [dodd_A_005_mod.jpg]

TAGS: Land Use Plan for Pine Mountain, mid-1930s, Katherine Pettit, Ethel de Long Zande, physical environment, buildings, landscaping, built environment, Mary Rockwell Hook, Harlan County KY, women architects, Julia Morgan, Hindman Settlement School, horse and train travel, fundraising speech, Old Log, Big Log, architectural planning, school children, farmland, Darwin D. Martin, farm engineers, Mr. Browning, Burton Rogers, William Creech, subsistence farming

LAND USE Plan for Pine Mountain Mid-1930s

When Katherine Pettit and Ethel de Long Zande began their visioning dialog for a school in the mountains of eastern Kentucky, they had many discussions regarding what the physical environment of their school would look like; what buildings would be necessary and how those buildings might be situated on the land; how the land should be landscaped and how buildings might be integrated with the natural landscape — and a myriad of other plans associated with the built environment and the existing terrain.

In 1913 the services of Mary Rockwell Hook, a Kansas City, Missouri, architect, were engaged by Pettit and de Long to help them in their planning process for the 426 acres of land they had secured in Harlan County, Kentucky. Miss Hook had never met either Miss Pettit or Miss de Long before she received their letter inviting her to work with them to create a school for children of the area.

Miss Hook was one of the first women architects in the United States along with her colleague, Julia Morgan, who designed the so-called “Hearst Castle” in San Simeon, California, and was a student at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts Architecture Academy in Paris, France, in 1905.

She had been introduced to Pine Mountain through a mutual friend at Hindman Settlement School, where both Miss Pettit and Ethel de Long met and worked. Hook’s friend at Hindman had a mutual friend at Wellesley College and she recommended Hook to Pettit. With the invitation in hand and on the mutual friend’s recommendation, Hook packed up and began the adventure of getting from California where she was working, first to Hindman and then to the proposed Harlan County, Kentucky, school site. Her story of that physical journey in 1913 played a role in her own mental design journey for the new school.

Hook agreed to come to Pine Mountain to discuss the School and its proposed building plan under two conditions:

1. That, [if] after talking things over and they discovered their architectural ideals were radically different, that they would not proceed;

2. That, if she took on the work, she would want to be present at the very start in order to lay out a comprehensive plan for the whole development.

Mary Rockwell [she was not yet married] began her long journey to Kentucky and her life-long fascination with the Pine Mountain Settlement School. She took a train across the country to near Hindman Settlement School in Knott County, KY. She was met by a gentleman and a horse sent by Miss Ethel de Long, who was at Hindman where she was just ending her employment. Mary Rockwell then rode the twenty-six miles from the train station to the Hindman Settlement School where she reviewed the central buildings at the School and spoke with the staff.

Hindman had been co-workers Katherine Pettit and May Stone’s first settlement school in the mountains of Eastern Kentucky and knowledge of that facility, its construction, and its functions were important elements in shaping Mary Rockwell’s understanding of rural social settlements. She also attended the commencement ceremonies of the institution and learned of the educational framework that joined academics with industrial training. The following morning she was assigned a horse by the Hindman School and she prepared for the arduous journey to the new Pine Mountain Settlement site.

The distance to Pine Mountain on horseback from Hindman was some fifty miles and required overnight stays with local families. On her journey to Pine Mountain, she was accompanied by Ethel de Long and others. At the new school site she was received by Katherine Pettit and her fledgling staff. On receiving Miss Rockwell, she was told the horse was a “gift” horse. Pettit, always in the thrifty mode, reportedly sent the horse back to Hindman, saying she could not afford to pay the gift’s upkeep, but Miss de Long and Miss Rockwell were there for their lifetimes.

Mary Rockwell (Hook) describes her journey and those first few days at Pine Mountain in a brief sketch, which is part of a later speech she gave to promote Pine Mountain Settlement School and to raise money for the School in 1920. The speech is among Mary Rockwell Hook’s early records in the archive at Pine Mountain Settlement School. The following is an excerpt:

For the first week, we three [Katherine Pettit, Mary Rockwell, and Ethel de Long] tramped over their acres, studying the different streams for water supply, levels and sites for buildings and gradually laying out a comprehensive plan for the complete development of a school of industry for 150 children. Our policy, in general, was to treasure all the lower lands for agriculture as every inch would be needed to feed the school, to use the steeper places for building, to concentrate all buildings of a public nature toward the center of the property and to use the two flanking ends of our valley for cottages.

Near the entrance to the property was a tumble-down log cabin with remains of two lovely stone chimneys at the ends. This we decided to restore for our first building and it is known as the ‘Old Log House.’ The next effort, way at the end of the valley, overlooking a stream that is thick with rhododendron, was to be Miss Pettit’s house. The logs that were hauled for this house were the most beautiful I have ever seen. Some of them were forty-two feet long and all uniformly 5 x 12 inches. When I see people who wish to imitate a hand-hewn beam having then hacked up with an axe, I always think of the smooth perfection of Miss Pettit’s beams. This house we called ‘Big Log House.’ It is the home of twenty-five children. We knew that logs were too expensive to continue to use as a building material, much as we regretted it. There was no sawmill anywhere, so the only thing to do was to get one and operate it. This was done and it has become a great factor in the community. The raw materials out of which a great school had to be built were right about us; These were great boulders of rock, tall straight chestnuts, oaks, and poplars. Ethel de Long’s oratory, for someone, had to find the funds and the courage of them both. No man in the district had ever built anything but a log house, usually one room.

[Go to ARCHITECTURAL PLANNING FOR BUILDINGS – A TALK BY M.R. HOOK

for the complete transcription of Mary Rockwell Hook’s speech.]

Mary Rockwell (Hook) was intrigued by the Pine Mountain Settlement School proposal. After her initial journey to the Pine Mountain valley, she was at once enchanted by the enthusiasm of Pettit and de Long but, more, she was enchanted by the land. She continued under the spell of the rugged land in all her planning.

While she began a relationship with the School as its architect, her work as its landscape architect was equally important. She reportedly established a land-use guide, soon designed her own summer home at the School, where she could live on-site, and later became a board member charged with recommendations on buildings and grounds. She continued her involvement with the School until she was unable to travel, all the while keeping a sharp eye on the School’s use of land and buildings through her many friends at the institution. She was still engaged with the School into her 90s and lived to be over 100 years old.

LAND USE Plan for Pine Mountain Mid-1930s:

ETHEL DE LONG AND EARLY LAND-USE OBSERVATIONS

Ethel de Long in her first Dear Friends Letter, 1913, describes much of the clearing activity during the first year

My dear friend:

I wish you could be here today, in the midst of this wilderness where we are building a settlement school, and see the beginnings of things. It takes a long time to get two-hundred and thirty-four acres of neglected land in shape for a model rural school but if we grow a little discouraged now and then we have only to go and watch “Carter” Coots and Solomon Day working against the weeds and underbrush along our creek banks with the love of battle plain in every stroke of the scythe, — the true pioneer’s Joy in getting the best of nature. With such a spirit we feel sure wonders can be accomplished.

If our neighbors’ hogs annoy us because they consider our first, modest attempt at a garden a pigs’ paradise with no St. Peter to guard the rickety stake and rider rail fence, we listen to the woodmen far up the Mountain, cutting locust posts for the five-foot “woven wire, hog—proof” fence we want to put around our paradise this fall. When we have not so much as a plank for a tiny bookshelf in this country of wonderful trees but no sawmills, we think of our splendid mill, given us by [a] friend who well understood our needs, waiting and ready for the great chestnut and poplar logs that are being cut from the School forest. We long for room to take in the children (and just how irresistible they are you can see from our summer kindergarten teacher’s testimony that in all her ninety-two enrolled in Cleveland she has none so winning as her little Pine Mountain Brit [Brit Wilder] — the same who, mindful of a past punishment, one day said to her, “I reckon you’ll have to sot me on the Lonesome Seat, I ain’t aiming to hurry this morning” ; when we feel with the fathers and mothers hereabouts that year is a right smart spell to wait for a schoolhouse we can write you, our friends outside, of our great need for one and ask you to help us build it!

I called this a wilderness from the phrase of a conspicuous literary man who visited us this summer and said he thought us the most fortunate of people with such a chance to build a school in the wilderness. His enthusiasm sprang from the fact that our mountains, remote, undeveloped, and rough though they are, are full of children. Up and down Greasy Creek neighbors live scarcely more than a “sight” apart and Lick, Rockhouse, Laurel, and Sang branches are not mere lonely streams girt with magnificent rhododendron thickets but have each its own homesteads and hearth fires. …

— Ethel de Long, Dear Friend Letter

LAND USE Plan for Pine Mountain Mid-1930s: LAND-USE GUIDE

A land-use guide possibly established by Mary Rockwell and endorsed by Pettit and de Long is one of the most intriguing documents left to the School. In many ways, it is a forerunner of the environmental programs that later evolved at the School. The attention given to the natural flora and fauna of the area guided both the built environment and through the years the founder’s 1913 plan also guided changes to the physical landscape of the institution — and there were to be many changes. For example, this letter from Katherine Pettit [?] to Darwin D. Martin, a member of the Board of Trustees, describes the efforts to remediate the flooding of the main farmland in front of Old Laurel House I and across the stream to the Office.

[image # P1050683]

July 12, 1929

My dear Mr. Martin:-

Do you remember that the very last problem you took up with me before you left here in May was the straightening of the creek [Isaac’ Creek, aka Isaac’s Run] in front of the Office, and you were so anxious to have it done that you asked me to send to the State University for a farm engineer to come and counsel us. And I promised you that I would do whatever he said.

He came yesterday, a very able and wise man, and he spent much time going over the whole situation, asking questions and thinking about it. He even went away down on Greasy to see what the situation was there and up the head of the creek [Isaac’ Creek, aka Isaac’s Run].

He thinks that if we do just as you suggested — begin to straighten the creek nearby the swimming pool on to the place just in front of the office — that they will solve the problem of flooding our garden. He told Mr. Browning [Farm manager] just how to do it, although he said what Mr. Browning had suggested was just what he would have done. And they think it will cost around $500.00. We are beginning it just as soon as we get more of our farm work done if you still want us to do it. I shall be glad to hear from you about it right away.

He advises as not to do anything about repairing the creek in the mill yard [Saw Mill Hollow] until we get this done — that this is the very first and most important thing to do.

Faithfully yours,

[unsigned copy, probably Katherine Pettit]

Though advanced in age, Mary Rockwell Hook continued to maintain her consultations with Pine Mountain, first from Kansas and later from her Siesta Keys, Florida, home. She held a particularly deep affection for Burton Rogers, (School Principal and the Director of Pine Mountain Settlement from 1941 until 1983). She dedicated her autobiography, “This and That“ to Burton and kept up a lively correspondence with him until her death in 1978 at the age of 101.

One of the stories that seemed to stay with Mary Rockwell Hook was one that described the travels of the Secretary of the Department of Agriculture, who was in eastern Kentucky about the same time as Hook’s first journey into the region. She relates that as the government head rode through the area studying the resources and meeting with the “leading spirits of the neighborhood,” he was directed to Uncle William Creech, who gave the land for Pine Mountain Settlement. Trying to understand the economics of the region, the Secretary asked Uncle William, “About how much money does it take for an ordinary family to live upon per year?” To which Uncle William is reported to have replied, “Well, for an ordinary family of, we’ll say, an even dozen, it would take in the neighborhood of $25.00 a year.”

This was perhaps the best endorsement of the subsistence farming practiced in the region and of the importance of farmland to the lives of the surrounding community. Subsistence farming has many negative connotations and nay-sayers but the lessons to be learned in this close association with the land is a lesson that is too quickly going away. The later land-use planning owes much to the subsistence farming practices of those who came first to the rich Pine Mountain valley.

LAND USE Plan for Pine Mountain Mid-1930s: CONTENTS

Landscape plan for Pine Mountain – landscape plan needs no fundamental change; must preserve what we have to reflect spiritual ideals of the school; must keep a natural setting; preserve weed land borders ; reflect wild beauty in foundation plantings ; cultivation must not dominate the native pattern; must follow founders’ ideals where possible; avoid artificial effects ; maintain harmony in the details ; [pages 1-3]

General considerations that should govern all landscape work at Pine Mountain [page 3]

Details that need attention: [page 3]

Foundation Plantings – need to be thoroughly done over; when to transplant; use Indian arrowweed; Laurel House plantings ; [pages 3-4]

Stream Banks – use of rock walls; shrubs will hold big tides ; [page 4]

Unused Land – plant fruit trees between road and branch; plant trees for cabinet wood on Grape Vine Knoll ; [pages 4-5]

Road Edges – problem of cinders washing into grass; need retaining walls ; [page 5]

Laurel House Garden – need for a flower garden ; care of bulbs ; [page 5]

New Planting – need to mask the dump; nuisance of honeysuckle; preservation of grass; chapel plantings; Infirmary Hill should not be thinned; cultivate natural flower gardens; develop Snake Path; a possibility of outdoor theatre ; [pages 5-6]

Outdoor Living Rooms – wildwood living room at each house; possibility of outdoor theatre ;

A Few Negatives – nuisance of honeysuckle; paths cause gullying;

GALLERY: LAND USE Plan for Pine Mountain Mid-1930s

- Mary Rockwell Hook, Land Use Plan, p. 1. [hook_folder_030.jpg]

- Mary Rockwell Hook, Land Use Plan, p. 2. [hook_folder_031.jpg]

- Mary Rockwell Hook, Land Use Plan, p. 3. [hook_folder_032.jpg]

- Mary Rockwell Hook, Land Use Plan, p. 4. [hook_folder_033.jpg]

- Mary Rockwell Hook, Land Use Plan, p. 5. [hook_folder_034.jpg]

- Mary Rockwell Hook, Land Use Plan, p. 6. [hook_folder_035.jpg]

- Mary Rockwell Hook, Land Use Plan, p. 7. [hook_folder_036.jpg]

- Mary Rockwell Hook, Land Use Plan, p. 8. [hook_folder_037.jpg]

- Mary Rockwell Hook, Land Use Plan, p. 9. hook_folder_038.jpg

TRANSCRIPTION: LAND USE Plan for Pine Mountain Mid-1930s

[page 1, image: hook_folder_030.jpg]

In its main outlines the landscape plan for Pine Mountain has been satisfactorily established and needs no fundamental change. The location of new buildings and the re-location of roads, when an adequate road over Pine Mountain brings more traffic, can be left until the need arises. For the present the landscape problem is to preserve what we have. And what we have is quite unusual and very much worth preserving, Also it is more perishable than It seems. It is a very beautiful native setting for the school plant — a setting that says quite plainly to the casual visitor that one of the Ideals of Pine Mountain is the preservation of the best elements in mountain culture and mountain character. For the founders of Pine Mountain knew that the physical characteristics of the land and the buildings expressed the spiritual ideals of the school. Therefore they wanted to keep the native character of the landscape setting and took, through the course of years, unimaginable pains to preserve each detail that contributed to the picture of a characteristic mountain valley. It is its fittingness that makes the landscape pattern of Pine Mountain appeal immediately to every stranger that has any sensitiveness to beauty.

This harmony comes from intelligent effort In two directions — first the painstaking preservation of those borders of the weed land which can be left to nature — the woods about the reservoir and Open House, Saw Mill Hollow, Pole House Hill, the steep slope of Infirmary Hill, etc., and secondly a more or less conscious imitation of the character of this wild beauty in the planting about the buildings. The character of the Pine Mountain landscape is not in the mown lawns or the Laurel House [Laurel House I] flower garden, but In the forest wall of Pine Mountain, the rhododendron thickets that fringe the branch, the hemlock, pine, laurel, and dogwood that have always been here. The cultivated fields, the lawns and flower gardens and buildings make agreeable contrast but must not dominate the native pattern.

[page 2, image: hook_folder_031.jpg]

The more the property is used and the more the school grows the harder it is to keep this look of inevitable fittingness, but if the ideal is clearly comprehended and its importance appreciated it is not impossible. The founders had constantly in mind their impression of the valley before the first building was begun. For us who come later it is hard to hold the right concept, being influenced by departures that have already been made from that original standard. These departures are for the most part compromises and concessions to necessity. They should not encroach upon the ideal. For instance, if a proper setting for the church-house as seen from the entrance demands a lawn, it does not follow that lawns per se are desirable and should be multiplied or, if the clearing of land for tillable fields is good, that the clearing of land which has no agricultural value is equally good. Briefly, a tendency toward park like perfection and artificial effects must be guarded against. They are the easily achieved commonplaces.

The attainment of the right Pine Mountain picture is a matter of innumerable harmonious details. For example the thicket behind the church-house [Chapel] with Its redbud and iron weed and carpet of sweet William and anemones and violets is a piece of perfection as it is, and unless an important use for that piece of land should develop, it is worth considerable effort to keep its native loveliness as a part of the whole Pine Mountain picture. The incessant care that has been lavished upon the growth about Big Log, the wild garden on the rock ledge and the thicket opposite contribute to the impression that the house gives of perfect appropriateness within and without. It is the accumulation of just such details that makes the landscape character of the whole. Strangers may not be able to analyze it, but the impression is not lost upon them. They recognize the mountain character at first sight of the grounds and feel its suitableness.

[page 3, image: hook_folder_032.jpg]

These are the general considerations that should govern all landscape work at Pine Mountain. For the rest there are a good many details that need attention.

Foundation Plantings

The planting around all the buildings has outgrown its purpose and should be thoroughly done over. The choice of native hemlock, rhododendron and laurel is good, generally speaking, and is probably worth the trouble that will be necessary to get good results. In some instances, as at Laurel House where the hemlocks have been pruned to bare stems below where foliage is wanted, and bushy tops in front of the windows, there should be light. It will be necessary to cut the trees, grub out the stumps and replant small hemlocks, say three feet high and three to four feet apart. In other cases where the hemlocks are not very large it will be sufficient to cut out the tops to the required height and cut back the side branches, then keep the tops trimmed to the proper shape and size.

If most of the hemlocks in any one planting are too big, it will be better to replace them by degrees rather than remove all at once and leave the building bare of all planting.

For the most part the rhododendron and laurel used in foundation planting does not look thrifty. But as there is nothing else as desirable from every point of view, the labor used In securing good plantings would probably be well spent. Shrub areas where the laurel and rhododendron look bad should be dug out to a depth of 20 feet and filled with oak leaf mould [sic] and woods dirt from areas where rhododendron is growing. Neither shrub will endure any trace of lime in the soil. Therefore it would be futile to introduce fresh soil from the north side of Pine Mountain where the outcrops of limestone give the soil an alkaline flavor. And neither shrub will endure dressings of stable manure.

Probably the best time for transplanting rhododendron and laurel will be at the end of the winter before the last hard freeze though any time…

[page 4, image: hook_folder_033.jpg]

…between the first frost and the middle of March is possible.

Another shrub useful with rhododendron and laurel and less particular as to soil and exposure Is Indian arrowweed. It might be used with the others on southern exposures that possibly would prove too hot and dry for rhododendron.

At Laurel House the foundation planting on the north side and at the north east and north west corners should be worked out in laurel, rhododendron and hemlock. But around the kitchen and laundry wings, where the windows are lower, It will be well to keep to the garden shrubs and perennial plants that are already established. They will need cultivation and fertilizer, but probably few additions.

Stream Banks

Rock walls on the stream banks such as are being built between the swimming pool and tool house bridges will prove most satisfactory. Elsewhere it may be enough to plant willow and alder. The more shrubby growth on the banks, the better they will hold in big tides. Willow, and I believe also alder, will root from cuttings of half ripe wood and it would be worthwhile to make rather thick plantings wherever the banks are unprotected by stone walls. These shrubs must then be protected as insurance against wash of soil in big tides. They can be thinned and pruned if necessary but encouraged to root freely.

Unused Land

The strip of ground between the road and the branch from the office to the swimming pool is going to waste and might be put to use. Fruit trees – peach, pear, plum, cherry or apple might be planted there, or two rows of raspberries. Or, if a low retaining wall were put in to hold the road, it might be graded level and used for strawberries, asparagus and rhubarb.

[page 5, image: hook_folder_034.jpg]

Another neglected area that should be put to use is Grape Vine Knoll. Vines and fruit trees having been tried and found unsuccessful. It might be worthwhile to experiment with black walnut for the wood, always in demand at the shop. There is not a great deal of walnut and cherry on the place, but wherever there is a tree it should be protected and kept for cabinet wood when large enough to cut.

Road Edges

The wash of cinders from the roads into the adjoining grass is a problem that is hard to cope with. In some places where the road is higher than its borders, as between the entrance gate and the tool house, low retaining walls that rise four or five inches above road level would help keep the road surface from washing Into the grass. Such protection would do away with the unsightly bare spot north of the tool house which now suffers from a flood of cinders.

Laurel House Garden

The school needs a flower garden to furnish flowers for the chapel and the dining room and Laurel House Garden should do this. But it requires constant cultivation and intelligent supervision. This is not time wasted, and the work put into it may be regarded as quite as educational as that put into the farm. The horticultural accumulation of years will not survive a few seasons of neglect.

The thousands of spring bulbs that have been increasing for years In this garden made rather a poor show this year. It may be that they are suffering from having the tops cut off too soon after flowering so that the bulb has not the means to store up for next season. It is a good rule to let the leaves remain for at least six weeks after the flowers have gone, or until the foliage is about half brown.

New Planting

There are a few places where new planting could be done to advantage. There is the dump, conspicuous to all visitors as they cross the bridge over Greasy, and most unsightly. Until it is finally filled and covered it…

[page 6, image: hook_folder_035.jpg]

…will continue to be an eyesore. But planting would make it less conspicuous. The angle between the road and the mine, and the road to the bridge might be spaded, fresh acid soil added and rhododendron and hemlock set rather closely in an extensive planting to mask the dump. Probably also it would be well to protect it by a fence. The old approach to the gate, by a foot log burled in rhododendron gave a most favorable impression. It would be worthwhile to put some trouble into improving the present far from attractive approach.

In front of the church house where redbud and dogwood are missing along the wall, these should be replaced. Three dogwoods and two redbuds, 8′-10′ trees if possible should be set next autumn, or preferably, early in March. It will be worthwhile to dig out holes four feet In diameter and two feet deep and fill with good loam.

And, speaking of the church-house [chapel] grounds, the pines on either side [of] the path ought to be kept pruned. Perhaps it is not too late to cut the larger one just above the second of branches and keep it and its neighbor trimmed back to small size.

The thinning done last year on the steep slope of Infirmary Hill was a mistake. That slope, which is too steep for agricultural use, should be kept solid wild growth and the rhododendron, and pine and laurel that are there should be encouraged and added to, rather than removed. It could be made a particularly beautiful bit,—a sort of museum to preserve the loveliness that once was all through the valley and up and down Greasy,—much as Aunt Sal’s house preserves the old time pattern of indoor life. Mrs. [Lexine] Baird’s plantings last spring along the path to the Infirmary were an excellent start In this direction. Galax and arbutus, which will not grow in most parts of the grounds do well here and should be cultivated. And especially laurel and rhododendron should be planted along the path and wherever the growth looks at all thin.

[page 7, image: hook_folder_036.jpg]

Similarly such ledges as that opposite Old Log should be regarded as natural flower gardens and cultivated accordingly. New pockets of black dirt ought to be continually filled in and planted with ferns and suitable wild flowers. There is usually some worker who has a knack for such wild gardening and should be encouraged to do it. Such places as this need constant attention, and, well done, are very telling In the whole picture.

The Snake Path is another feature that needs development. It suffers now from injudicious and too thorough trimming, and should be replanted with a view to creating an enclosed path in a natural setting. Running between the brook and the hill, where its borders cannot be cultivated, for practical purposes it is waste land. For aesthetic purposes it Is invaluable. Its edges should be planted to give the most perfect illusion of an unspoiled mountain path,—-part shrubs such as Indian arrow wood, spice bush and alder, part small trees as holly, dogwood, redbud and cedar for shade. If thinning is necessary it should be done with caution and under studied direction so that it will never again look bare and uninteresting.

Outdoor Living Rooms

It was Mrs. Zande‘s idea that each house should have its own wildwood living room for Sunday night suppers, and odd moments of relaxation and quiet — the Big Log, Leanto, [Lean-To] the fireplace across the branch from Boy’s House, the Hollow at Far House, etc. They serve a purpose and should be kept up in every way that will conduce to their use.

A bit below the plant house [Electrical Power House] there is a small almost flat place where the branch swings away from the Snake Path. It is large enough for a stage and might some day be developed as an outdoor theatre, with stone benches set into the side of Pole House Hill above, the ground graded and planted with turf and wings and back drop worked out in cedar planting. At present there seems to be no particular need of such a theatre but the site is exceptional and should be kept In mind in case it is ever desirable to…

[page 8, image: hook_folder_037.jpg]

…develop it in that way.

A Few Negatives

One of the nuisances that must be forever guarded against is honeysuckle. It has its use on very steep banks where nothing else will grow, say a 45 degree slopes or steeper. But elsewhere it is an unmitigated nuisance rapidly covering whole areas or grass and swallowing whole thickets It is also an ideal haunt for snakes. There is some very heavy growths of ivy that should be warred upon—to the west of the entrance gate, for instance, around the ledge opposite Old Log; around the rocks past of the Tool House; above the path between the Office and Old Log; at the west door of the Office; around the Far House coal house; on the east edge of the schoolhouse lawn, etc. In some cases, as at the entrance gate and at Far House, the whole area should be spaded, forked and raked repeatedly until every root Is gone, and after a whole season of such intermittent attention, replanted. At Far House it is swallowing up garden plants that are worth saving. There is enough young rosa rugosa to replant both sides of the coal house after the honeysuckle is gone. On the slope of the hollow, across the path from the coal house there are day lilies, roses, Washington bough etc., which should be rescued and reset after the honeysuckle is exterminated,

A perennial trouble is to preserve the grass at the edge of the stepping stones. Brush placed beside the stepping stones in early spring when the grass is starting and the ground is soft, helps some, but mostly it is a question of patiently training heedless children to take an interest In the looks of their premises and keep off the grass borders. Something particularly drastic in the way of brush, fences and admonition is needed at Boys House where the lawn adjacent to the paths is especially shabby.

Another difficulty is to prevent the use of the paths when they are not wanted, as for instance on steep slopes where wash and gullying will result. There has always been a tendency to make a path from Far House down…

[page 9, image: hook_folder_038.jpg]

…the hill to the Snake Path. It is an unnecessary short cut and should be prevented for it will ruin that slope. It is to be hoped that in erecting the new Industrial building [Draper Industrial Building] the native growth behind it will be carefully protected. It is easier to remove afterwards as required, than to replace what the proper setting of the building calls for.

**[Note: Apparently there is some dissent regarding the authorship of this document as the notes on the document indicate.]

[Handwritten notation, crossed out] “Undoubtedly done by Mary Rockwell Hook.”

[Additional notation handwritten by another, probably Mary Rogers] “Must be Abbie Christensen.”

LAND USE Plan for Pine Mountain Mid-1930s: AUTHORSHIP

A recently (2018) found letter from Katherine Pettit begins to shine more light on the question of who might have written this outline for “Land Use” at Pine Mountain. Pettit refers to “Ruth” when describing the first campus landscape plan. It is believed that this mysterious “Ruth” might be Ruth B. Gaines who, like Pettit was fond of gardening and was sensitive to the native plants at the School and the general aesthetics of the landscape that forms the background to the school buildings. The discovery of the Pettit letter still awaits verification, but any one of the suggested authors would have been satisfactory. Whether Mary Rockwell Hook, Abby Winch Christensen, or Ruth Gaines, the resulting remnants of the plan may still be seen when visiting the campus.

See Also:

GUIDE TO BUILT ENVIRONMENT with links to pages for each PMSS structure

BUILT ENVIRONMENT, history and maps

SERIES 10: BUILT ENVIRONMENT, inventory of collection

MARY ROCKWELL HOOK, biography