Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 09: BIOGRAPHY – Staff

Series 15: ARTS AND CRAFTS

The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes

By Helen Wilmer Stone Viner

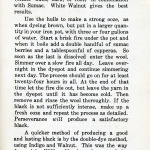

“Dyeing.” Two women with buckets and vat. [Aunt Sal and Ethel de Long ?] [nace_II_album_062.jpg]

KATHERINE PETTIT Dye Book

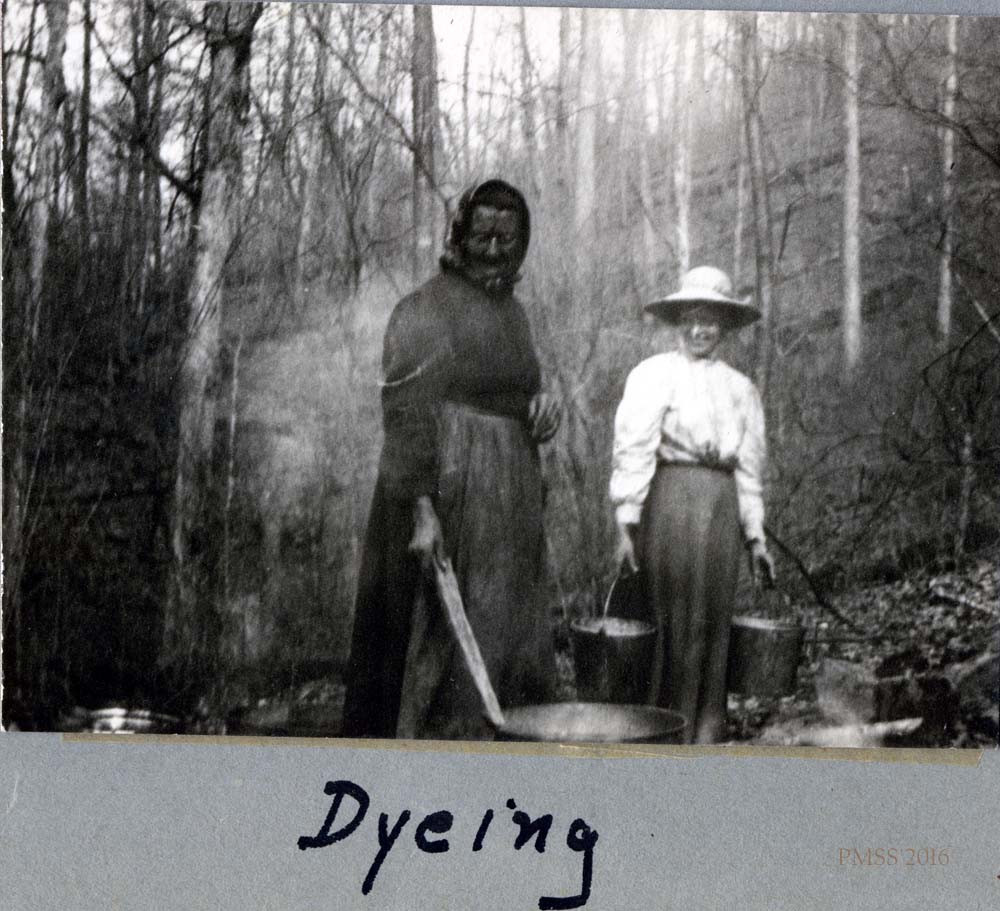

KATHERINE PETTIT BOOK OF VEGETABLE DYES

by Helen Wilmer Stone Viner. PMSS Housemother & Weaver 1914-1922

TAGS: vegetable dyeing manual, Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes by Helen Wilmer Stone Viner, H.E. Scrope Viner, Saluda NC, Excelsior Printers, Vassar College, Marguerite Butler, John C. Campbell Folk School, tripod iron pot, Blue Pot, indigo dye, dye recipes, Mountain Homespun, craft shops

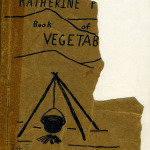

The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. [pettit_dye_book_001.jpg]

The Katherine Pettit Dye Book, or more correctly The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes, is a unique manual for creating and using vegetable dyes. Compiled by Helen Wilmer Stone Viner (c. 1891-1978), and H.E. Scrope Viner, her husband following her departure from Pine Mountain Settlement School, the small book is well-known in the weaving literature of the Southern Appalachians.

Before her marriage, Helen Wilmer Stone worked at Pine Mountain Settlement School from 1914 to 1922 as a housemother and a weaver. She discovered vegetable dyeing through Katherine Pettit, one of the co-directors of the School at the time. This small booklet was created in Saluda, North Carolina, where Helen Wilmer Stone settled, met and married H.E. Scrope Viner after leaving the School.

The booklet is based on Viner’s work at Pine Mountain and is one of the more unique manuals for vegetable dyes in the Southern Appalachians. It was published by Excelsior Printers in Saluda, North Carolina, in 1946, where Stone met her husband and settled.

HELEN WILMER STONE: Pine Mountain

Helen Wilmer Stone, worked at Pine Mountain during some of its most foundational years when Katherine Pettit and Ethel de Long were co-directors and when her friend Marguerite Butler was a primary staff member. Both Viner and Butler were graduates of Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, New York, and their friendship brought them to Pine Mountain and persisted through their lifetimes.

Helen Wilmer Stone left Pine Mountain in the same year that Marguerite departed. Helen Stone settled nearby in Saluda. Butler left for Brasstown, North Carolina, to work with Olive Dame Campbell at the new John C. Campbell Folk School.

Old Log. View of east end with blue pot [?] and tripod. [II_5_old_log_office_207a.jpg]

HELEN WILMER STONE: After Pine Mountain

Following their early work at Pine Mountain during the School’s foundational years, Stone and Butler were both well-seasoned settlement workers. Their talents were recognized by Olive Dame Campbell as she struggled to build the new folk school at Brasstown. Butler had traveled to Denmark with Campbell and had been inducted into the Danish folk school ethos. Stone, like Butler, was somewhat conflicted by her departure from Pine Mountain, as the years at Pine Mountain had been good ones. Unlike her friend Butler, she struck out on her own and used the talents she had acquired at Pine Mountain and her contacts in the Saluda area to follow her interests in mountain craft.

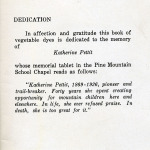

Her affection for Pine Mountain and for Katherine Pettit is seen in her dedication of this manual of dye processes to Katherine Pettit, Co-Founder and Co-Director of Pine Mountain Settlement School (1913-1930). Pettit, an avid collector of mountain “kivers” and dye craft, no doubt left her indelible mark on Stone as she did so many others at the School.

DEDICATION: Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes

In affection and gratitude this book of vegetable dyes is dedicated to the memory of Katherine Pettit whose memorial tablet in the Pine Mountain School Chapel reads as follows:

“Katherine Pettit, 1869-1936, pioneer and

trail-breaker. Forty years she spent creating.

opportunity for mountain children here and

elsewhere. In life, she ever refused praise. In

death, she is too great for it.”

The cover of the small booklet shows a tripod iron pot often used for vegetable dyeing in mountain homes and at the school.

Katherine Pettit had a lifetime love of mountain craft and particularly weaving. [See: KATHERINE PETTIT Weaving at PMSS Beginnings.] Her large collection of coverlets held by Transylvania University in the Bodley-Bullock House on Gratz Place in Lexington, Kentucky, is remarkable for its breadth and variety of design and technique. Within the coverlet collection, the use of “Blue Pot” is repeated frequently in the textile description.

BLUE POT Indigo dye

“Blue Pot” is indigo dye, a complicated dye bath used by many mountain dyers and weavers. It was a process that both enchanted and confounded the staff at Pine Mountain. The deep blue produced by the plant indigo is seen throughout the world in many early textiles and prized for its stability and intense shades of blue.

An example of the deep blue, almost black, color may be seen below in the weaving sample from Katherine Pettit’s collection.

However, the process is not as simple as it may seem. Viner and other staff at Pine Mountain had exceptional difficulty with this particular “vegetable” dye and it is not surprising to see considerable attention paid to its processes in this small booklet. The use of more common mountain dyes such as walnut and madder provided easier results and often more successful dye batches. Further, it was less labor intensive than the Blue Pot. Many of the the natural dye colors were fugitive (would fade with time) when compared to the infamous Blue Pot which is known around the textile world for its vivid color stability.

PETTIT Dye Book by Helen Viner

The Pettit-Stone-Viner booklet shares many of the eastern Kentucky and Appalachian regional recipes for dyes from flowers, trees, shrubs, vegetables, and other botanical sources. Viner’s compilation of techniques and recipes was a manual of practice that was derived from recipes passed down through families of weavers from many countries. The recipes were diligently sought after by serious weavers and dyers for decades but few had access to a comprehensive “book” of dyes. It was Helen Wilmer Stone Viner who changed all that.

The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes produced by Viner as a print run from a private Saluda, North Carolina, publisher, was small. As a proprietary publication, it soon disappeared from print.

There were earlier “recipe books” including a short section in the book on mountain craft published by Frances Louisa Goodrich. Her book, Mountain Homespun, published in 1935 and recently re-printed with an introduction by Jan Davidson, former director of the John C. Campbell Folk School, has a second appendix of dye plants and a small section (p.13-16) on dyeing that includes useful anecdotal information on the craft.

It is not known whether Wilmer Stone Viner had access to to Goodrich’s writing. What is generally suspected is that Goodrich was a solid source of her information and also seems to have had a direct influence on Viner’s knowledge of natural dyes. Allenstand Cottage Industries, Goodrich’s craft enterprise, competed somewhat with Viner’s Saluda business, The Weave Shop, and with the growing number of weaving craft shops that sprung up during the craft revival of the 1920s and later, including Biltmore Industries.

CRAFT SHOPS in Southern Appalachia

Many craft businesses sprung up in the southern Appalachians during this time particularly in North Carolina and at Berea in Kentucky. Clementine Douglas of the Spinning Wheel in Asheville, Edith Matheny and the Matheny Weavers, and Sarah Dougherty and the Shuttle-Crafters, to name a few early entrepreneurs featured vegetable dyed weaving.

The isolation of Pine Mountain Settlement never allowed ready access to a broad craft market of the touring public, but a brisk mail-order business allowed income to come to the School through marketing to major Northeastern buyers. During the years Wilmer Stone was in residence there was a concerted effort to market the Pine Mountain Settlement School weaving and other craft.

NATURAL DYEING: Access to Information

The digital age has made access to the Pettit-Stone-Viner booklet much easier for those interested in vegetable dyeing and in the many varieties of plants that can be called into use by craftspeople. For those who want to vary the colors of their wools, cottons and flax, Viner’s work and the work of later dye enthusiasts, has been greatly expanded the range of natural dyes. This extended access to other dye books and recipes and later government publications has made access and experimentation much easier for later natural dye enthusiasts.

For example, the small government booklet produced by the United States Department of Agriculture, Home Dyeing with Natural Dyes, authored by Margaret S. Furry and Bess M. Viemont in 1935, provides an expanded list of resources for natural dyes. This early government booklet, which was owned by Katherine Pettit, is also held by Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections. it makes a solid introduction to the skill of harvesting and preparing natural dyes. It was used as reference in later efforts to develop dyes at the School and it most likely was a source of many of Katherine Pettit’s recipes in her so-called dye book. The government manual is more technical in its approach to the process of using natural dyes, but the Pettit-Stone-Viner booklet is a delight to investigate.

A second digital copy of the Viner booklet is held by Hunter Library at Western Carolina University and comes from the collections of the John C. Campbell Folk School in Brasstown, NC. It has a rich commentary accompanying the online version of the manual which describes the relationship of Viner to western North Carolina and to John C. Campbell Folk School. See also the related papers for the Craft Education Project questionnaire prepared for the Southern Highland Handicraft Guild and the Southern Highlanders by Marian Glady Heard with Wilmer S. Viner’s assistance. The project carried forward the emphasis on sustainable craft in the Southern Appalachians and the educational value of such work as weaving and dyeing, vegetable dyers, and weavers. All are available through the Western University, Hunter Library Craft Revival website and digital archive.

**********

Helen Wilmer Stone Viner ends her manual with the following recommendation:

Here in this little book we have put down a few receipts for dyeing wool. From this small beginning the real dyer can go forward and have a grand time experimenting, and get his own palette of colors with which to work. Some will last forever, and some will fade gradually; the deeper and richer the shade the more permanent the color always.

Not everyone is a dyer; some have success and some do not, but any one will have an interesting time. For the colors, Blue and Rose, Indigo and Madder are the best. But for the other colors the woods, the flower-gardens are ours to experiment with. There is dye in roots, barks, flowers, hulls, leaves, and lichens, and many of these dyes have never been discovered, nor the mordants with which they are made fast. The dyer who has a real love of color and much patience can work all this out for himself. We hope this book will just be a beginning, and that you will go ahead and find many more lovely colors. Anyway, we know that is what Miss Pettit would wish!

GALLERY: Katherine Pettit Dye Book

NOTE: Though paginated, the page sequence in this booklet is not reflected in the assigned IDs for the images found below due to several blank pages at the end of the booklet.

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_001.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes.pettit_dye_book_002.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_003.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_004.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_005.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_006.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_007.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_008.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_009.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_010.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_011.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_012.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_013.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_014.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_015.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_016.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_017.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_018.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_019.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_020.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_021.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_022.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_023.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_024.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_025.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_026.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_027.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_028.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_029.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_030.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_031.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_032.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_033.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_034.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_035.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_036.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_037.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_038.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_039.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_040.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_041.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_042.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_043.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_044.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_045.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_046 .jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_047.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_048.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_049.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_050.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_051.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_052.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_053.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_054.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_055.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_056.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_057.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_058.jpg

- The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes. pettit_dye_book_059.jpg

TRANSCRIPTION: Katherine Pettit Dye Book

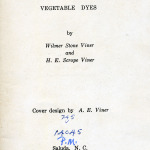

[Title page]

The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes

by Wilmer Stone Viner

and H.E. Scrope Viner

Cover Design by A.E. Viner

Saluda, N.C. The Excelsior Printers

1946

Copyright 1946 by Mrs. Wilmer Stone Viner

Printed in the United States of America

[PHOTOGRAPH OF KATHERINE PETTIT]

DEDICATION

In affection and gratitude this book of vegetable dyes is dedicated to the memory of Katherine Pettit whose memorial tablet in the Pine Mountain School Chapel reads as follows:

Katherine Pettit, 1869-1936, pioneer and trail-breaker. Forty years she spent creating opportunity for mountain children here and elsewhere. In life, she ever refused praise. In death, she is too great for it.

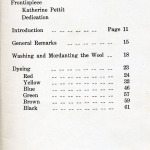

Table of Contents

Frontispiece

Katherine Pettit Dedication

Introduction _____________________________11

General Remarks__________________________15

Washing and Mordanting the Wool _________18

Dyeing _________________________________ 23

Red _______________________ 24

Yellow _____________________ 32

Blue _______________________ 46

Green ______________________ 57

Brown ______________________59

Black _______________________ 61

The Katherine Pettit Book of Vegetable Dyes

INTRODUCTION

In almost all American families we find treasures of the past that are carefully handed down from generation to generation, and the one that is greatly treasured perhaps above all is the hand-woven coverlet with its lovely delicate colors mellowed by time. What a history there is in these colors! In those bygone days you could not go into the store and from a color card pick out just the dye you wanted. The weaving by hand and coloring of these old coverlets was no small task. And perhaps because it was such a slow, tedious task is the reason why these treasures are so lasting and so dear to our hearts.

There seems to be an awakening of renewed interest in natural dyes throughout our country. Certainly there are no more beautiful colors than can be gotten from our native trees, shrubs, and flowers, and from the vegetable dyes that we import from other countries. These treasured bits of weaving of the past, the colors still bright, satisfying our eye with a peculiar beauty, surely are the best proof of the lasting qualities of those dyes. Nowadays interest has turned again to

11

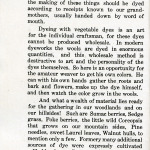

handmade things: you see more handlooms in homes; and delight is taken in reproducing the intricate patterns of the old coverlets. It seems fitting that the wools which go into the making of these things should be dyed according to receipts known to our grandmothers, usually handed down by word of mouth.

Dyeing with vegetable dyes is an art for the individual craftsman, for these dyes cannot be produced wholesale. In modern dyeworks the wools are dyed in enormous quantities, and this wholesale method is destructive to art and the personality of the dyes themselves. So here is an opportunity for the amateur weaver to get his own colors. He can with his own hands gather the roots and bark and flowers, make up the dye himself, and then watch the color grow in the wools

And what a wealth of material lies ready for the gathering in our woodlands and on our hillsides! Such are Sumac berries, Sedge grass, Poke berries, the little wild Coreopsis that grows on our mountain sides, Pine needles, sweet Laurel leaves, Walnut hulls, to mention only a few. Formerly many additional sources of dye were expressly cultivated – Madder in our flower gardens, and Indigo in the Southern States. Now Madder must

12

be imported from Europe and Indigo from China or India, while tropical dyewoods like Fustic and Logwood can, of course, only be obtained through importing houses.

When thinking over old receipts which have been used and passed on from one generation to the next, it is interesting to note how the chemist’s science again and again confirms the use of one or other ingredient for the use of which the old dyer can give no reason beyond the fact of its accepted necessity.

For example, the old receipts for setting up the Blue Pot call for home-made “Lye”. Chemistry shows the active ingredient of this extract to be Potash in a form most effective for the reduction of Indigo. So, from his practical experience, the early dyer was led to employ an essential chemical, obtainable in every household by homely methods. In each colonial home the ash-hopper was a familiar object, holding in store a crude ingredient of the soap kettle and the dyepot.

Again, the formulas for the preparation of lichens for the dyepot all spoke of the use of stale urine as a fundamental; and we now know that its constituent, ammonia, is needed to free the active principal, Orcin, and change it into Orcein, the essential coloring agent. For us, probably, the use of the chemical is

13

the easier method, but undoubtedly the homely formula was the more practical for the people among whom it originated.

Likewise in the old homely sayings, we find hidden scientific truths:- “A bright pot for a bright dye and a dark pot for a dark dye,” this is literally true since in many vegetable dyes there is tannic acid, which, combining with the inside of a black pot sets free an oxide of iron which will sadden bright colors.

The old colonial method of getting variegated effects on warp and filling was by tying wrappings of corn shucks around the material at intervals, protecting the chain in this manner by a waterproof covering from the action of the dye when the material was placed in the dyepot. The tied and dyed work of today is an echo of this.

14

In the following pages will be found receipts for preparing and using dyes from many natural sources, including those just mentioned; however, there are a few general hints which may help the dyer to obtain best results. If at all possible, dye out of doors, as sunshine and air are most helpful in obtaining bright colors. A Tripod can be erected of poles at very little expense and the dyepot hung from this by means of a chain and hook. Two pots should be kept for use, an iron one for dark and a brass pot for bright colors. “Don’t crowd the pot,” is an old saying, meaning you should allow plenty of water in all processes, so that the wool may be easily moved about. Stir the pot often, so that the dye may “take” evenly, and for the same reason, tie the wool in loose hanks, not tightly, or there will be light places in it, where the dye has not penetrated properly. Wool that has been mordanted and then has dried should be again damped before putting into the dyebath, to insure its taking up the dye evenly.

In using dye woods, berries, flowers, roots, etc., the materials can be tied loosely in cheese-cloth bags, to save the trouble later on of picking the bits out of the dyed wool; however, my experience is that the color comes

15

out more readily if the material is not so confined. Barks, roots, and hulls can be put into the dyepot first, and the dye extracted by boiling before the wool is put in; but when berries or flowers are the source of the dye, they had best be put into the pot at the same time as the mordanted wool, since prolonged boiling dulls the colors obtained from these sources. This especially applies to ‘ ‘dye-flower”, also to Madder, I find.

The time of year has a great effect on the results gotten when using vegetable dyes. In the Springtime all dyes from bark are weak, because at that time the sap, rising in the tree, dilutes the staining material in the bark which is the source of our dye. Again, as flowers and berries get mature they yield a duller dye. On the other hand, Sedge-grass gives its best maize color when it has been first dried.

The clear, crisp days of autumn are the best days of the year in which to get brilliant colors. The statement, “Vegetable dyes are most temperamental,” may sound rather fanciful, yet it is not unusual for two persons to employ exactly the same formula in dyeing, and still each get a different shade of color! Many factors influence the final result, and the more carefully each process is carried out

16

the more satisfactory will the product be. The most important points to this end are:-

- The cleanliness of the Wool.

- The composition of the Water used;-its hardness or softness will affect the quantities of dye or mordant required, and receipts must be read with this in mind.

- The Vessels in which the wool is dyed, -brass or copper for bright colors and iron for sober ones, after the old saying: “A bright pot for a bright dye, a dark pot for a dark dye.”

- The length of Time in mordanting, which process must not be hurried.

- The Weather, – bright colors can be gotten most satisfactorily on a bright day.

- The Dyes themselves, – it can almost be said that vegetable dyes give a slightly different color for each month of the year in which they are gathered, e. g. green walnut hulls gathered in September give a pinkish-brown, gathered in October the pinkish shade is gone!

17

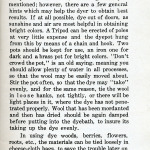

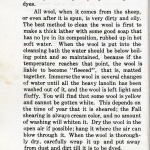

To prepare the wool for mordanting is the first important step in dyeing with vegetable dyes.

All wool, when it comes from the sheep, or even after it is spun, is very dirty and oily. The best method to clean the wool is first to make a thick lather with some good soap that has no lye in its composition, rubbed up in hot soft water. When the wool is put into the cleansing bath the water should be below boiling point and so maintained, because if the temperature reaches that point, the wool is liable to become “fleeced”, that is, matted together. Immerse the wool in several changes of water until all the heavy lanolin has been washed out of it, and the wool is left light and fluffy. You will find that some wool is yellow and cannot be gotten white. This depends on the time of year that it is sheared; the Fall shearing is always cream color, and no amount of washing will whiten it. Dry the wool in the open air if possible; hang it where the air can blow through it. When the wool is thoroughly dry, carefully wrap it up and put away from dust and dirt till it is to be dyed.

MORDANTS

While there are a few vegetable dyes that

18

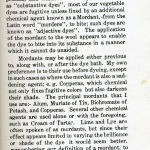

impart permanent colors to wool directly immersed in them without any intermediary process, and which are consequently known as “substantive dyes”, most of our vegetable dyes are fugitive unless fixed by an additional chemical agent known as a Mordant,-from the Latin word “mordere”, to bite; such dyes are known as “adjective dyes”. The application of the mordant to the wool appears to enable the dye to bite into its substance in a manner which it cannot do unaided.

Mordants may be applied either previous to, along with, or after the dye bath. My own preference is to their use before dyeing, except in such cases as where the mordant is also a saddening agent; e. g. Copperas, which chemical not only fixes fugitive colors but also darkens their shade. The principal mordants that I use are:- Alum, Muriate of Tin, Bichromate of Potash, and Copperas. Several other chemical agents are used alone or with the foregoing, such as Cream of Tartar. Lime and Lye are often spoken of as mordants, but since their effect appears limited to varying the brilliance or shade of the dye it would seem better, remembering our definition of a mordant, to class them separately, as brightening agents. Let us see how our mordants are used.

19

This is the most generally used of mordants. The best results are gotten from alum in combination with cream of tartar:- to one pound of wool use approximately four ounces of alum and one-quarter ounce of cream of tartar. Too much alum would tend to make the wool sticky. Heat the solution slowly, keeping just at the boiling point; and don’t neglect to make good the loss from evaporation by frequently adding more water as the solution boils away. The mordanting should go on for from a single period of one hour to treatment extending over ten days, according to what shade of color is wanted. For example, the best results were gotten when mordanting for Maddar by boiling the wool in the solution for half an hour each day for ten days consecutively, allowing the wool to hang in a damp dark place between times.

2. Muriate of Tin. This is a most important mordant. By using muriate of tin we get the most brilliant colors* It must, however, be used with care and the proportions in the receipt not exceeded, as its use tends to harden the wool, discoloring it slightly; used too strong it renders it harsh and brittle. Its effect is enhanced by addition of cream of tartar,- the proportions are, for one pound wool, one-half

20

ounce muriate of tin and one ounce cream of tartar. Keep the vessel covered, have plenty of hot water and boil slowly one hour.

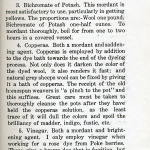

3. Bichromate of Potash. This mordant is most satisfactory to use, particularly in getting yellows. The proportions are:-Wool one pound-, Bichromate of Potash one-half ounce. To mordant thoroughly, boil for from one to two hours in a covered vessel.

4. Copperas. Both a mordant and saddening agent. Copperas is employed by addition to the dye bath towards the end of the dyeing process. Not only does it darken the color of the dyed wool, it also renders it fast; and natural grey sheep’s wool can be fixed by giving it a bath of copperas. The receipt of the old homespun weavers is “a pinch to the pot” and this suffices. Great care must be taken to thoroughly cleanse the pots after they have held the copperas solution, as the least trace of it will dull the colors and spoil the brilliancy of madder, indigo, fustic, etc.

5. Vinegar. Both a mordant and brightening agent. I only employ vinegar when working for a rose dye from Poke berries. These give a brown dye that is fugitive, but by immersing the wool, either before or after the dye bath, in a strong solution of vinegar the brown color is transformed to a beautiful rose, and this color is fast.

21

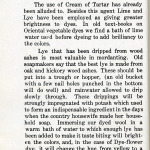

BRIGHTENING AGENTS

The use of Cream of Tartar has already been alluded to. Besides this agent Lime and Lye have been employed as giving greater brightness to dyes. In old text-books on Oriental vegetable dyes we find a bath of lime water used before dyeing to add brilliancy to the colors.

Lye that has been dripped from wood ashes is most valuable in mordanting. Old soapmakers say that the best lye is made from oak and hickory wood ashes. These should be put into a trough or hopper, (an old bucket with a few nail holes punched in the bottom will do well) and rainwater allowed to drip slowly through. These drippings will be strongly impregnated with potash which used to form an indispensable ingredient in the days when the country housewife made her household soap. Immersing our dyed wool in a warm bath of water to which enough lye has been added to make it taste biting will brighten the colors, and, in the case of Dye-flower dye, it will change the hue from yellow to a brilliant orange, almost a red.

22

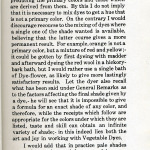

DYEING

I will now give the receipts which in practice I have found to be the most satisfactory in producing the primary colors and those which are derived from them. By this I do not imply that it is necessary to mix dyes to get a hue that is not a primary color. On the contrary I would discourage recourse to the mixing of dyes where a single one of the shade wanted is available, believing that the latter course gives a more permanent result. For example, orange is not a primary color, but a mixture of red and yellow ;-it could be gotten by first dyeing with madder and afterward dyeing the red wool in a hickory-bark bath, but I would rather use a single bath of Dye-flower, as likely to give more lastingly satisfactory results. Let the dyer also recall what has been said under General Remarks as to the factors affecting the final shade given by a dye,- he will see that it is impossible to give a formula for an exact shade of any color, and therefore, while the receipts which follow are appropriate for the colors under which they are listed, taste and skill can obtain an infinite variety of shade;- in this indeed lies both the art and joy in working with Vegetable Dyes.

I would add that in practice pale shades of a color are less satisfactory and less enduring than full ones.

23

Madder. This is a European plant cultivated nowadays in the Netherlands, France, and the Levant. Its botanical name is Rubia Tinc-torum. It has a yellow flower, however the root is the portion of tha plant of value to us, as the dye is obtained from this, dried and pulverised. Madder was grown in former days by the mountain people of the Appalachians to furnish dye for their homespuns. The art of cultivating the plant and extracting the dye was evidently brought originally by them from England, but that practice has now died out. I have found plants of wild madder in the overgrown corners of fields that have been long neglected. These plants yield a true madder dye, but very limited in quantity, making the use of wild madder impractical.

Madder contains two dyes, red and brown. Shades of red are liberated up to the boiling point, after that the brown shades are liberated and dull the red, hence in working for Rose colors it is most important to keep the temperature below the boiling point.

When aiming at a compound color, as Madder and Old Fustic, dye first in madder, remove the wool from the bath and put it into a separate bath of fustic. This is necessary as

24

the fustic requires to be boiled and the madder does not. The brightest result can always begotten by adding Cream of Tartar to the mordant.

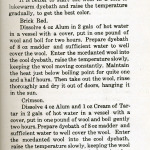

It is better to start the wool in a cold or lukewarm dyebath and raise the temperature gradually, to get the best color.

Brick Red.

Dissolve 4 oz Alum in 2 gals of hot water in a vessel with a cover, put in one pound of wool and boil for two hours. Prepare dyebath of 8 oz madder and sufficient water to well cover the wool. Enter the mordanted wool into the cool dyebath, raise the temperature slowly, keeping the wool moving constantly. Maintain the heat just below boiling point for quite one and a half hours. Then take out the wool, rinse thoroughly and dry it out of doors, hanging it in the sun.

Crimson.

Dissolve 4 oz Alum and 1 oz Cream of Tartar in 2 gals of hot water in a vessel with a cover, put in one pound of wool and boil gently two hours. Prepare dyebath of 8 oz madder and sufficient water to well cover the wool. Enter the mordanted wool into the cool dyebath, raise the temperature slowly, keeping the wool moving constantly. Maintain the heat just below boiling point for one hoar. Then take out

2S

the wool, rinse thoroughly and dry it out of doors, hanging it in the sun.

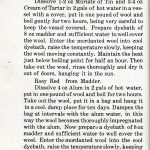

Scarlet.

Dissolve 1-2 oz Muriate of Tin and 3-4 oz Cream of Tartar in 2 gals of hot water in a vessel with a cover, put in one pound of wool and boil gently for two hours, being very careful to keep the vessel covered. Prepare dyebath of 8 oz madder and sufficient water to well cover the wool. Enter the mordanted wool into cool dyebath, raise the temperature slowly, keeping the wool moving constantly. Maintain the heat just below boiling point for half an hour. Then take out the wool, rinse thoroughly and dry it out of doors, hanging it in the sun.

Rosy Red from Madder.

Dissolve 4 oz Alum in 2 gals of hot water, put in one pound of wool and boil for two hours. Take out the wool, put it in a bag and hang it in a cool, damp place for ten days. Dampen the bag at intervals with the alum water, in this way the wool becomes thoroughly impregnated with the alum. Now prepare a dyebath of 8 oz madder and sufficient water to well cover the wool. Enter the mordanted wool into the cool dyebath, raise the temperature slowly, keeping the wool moving constantly. Maintain the heat just below boiling point for half an hour. Take

26

out the wool, rinse thoroughly and dry it out of doors, hanging it where the sun shines.

In all these receipts a variety of shades may be gotten by varying the time that the wool is left in the dyebath, however the paler shades are apt to be fugitive.

Cochineal.

Cochineal is a dyestuff consisting of the dried bodies of female insects found on the underside of leaves of several species of cacti, native in Mexico and Central America. These cacti are extensively cultivated for the purpose of raising the insects, which are periodically gathered and killed by heat.

Cochineal when bought from the chemist sometimes looks silvery and sometimes black. Either kind is equally good for dyeing, the differing appearance being due to the mode in which the insects were killed, those killed in stoves retain the natural white powdery covering, and silver-grey cochineal results; when killed by steam or hot water the insects lose this covering, and black cochineal is produced.

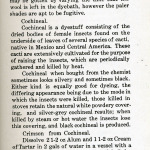

Crimson from Cochineal.

Dissolve 21-2 oz Alum and 11-2 oz Cream of Tartar in 2 gals of water in a vessel with a cover. Put in one pound of wool and boil for two hours. Prepare dyebath of 1 oz cochineal in

27

two gallons of water. Enter the mordanted wool into the dyebath, raise the temperature slowly, moving the wool constantly. Boil for two hours. Take out, rinse, and dry the wool in the sun.

Scarlet from Cochineal.

Mordant the wool for two hours in a vessel with a cover, 1-2 oz Muriate of Tin and 3-4 oz Cream of Tartar in two gals of water for one pound wool. Be careful to keep vessel covered. Prepare dyebath of 2 oz Cochineal in enough water to well cover the wool, enter the wool when the dyebath is warm and raise gradually to the boiling point. Boil for an hour, keeping wool moved about at intervals. Remove wool, rinse it in clear water and dry in sunshine.

Kermes.

This dye is of the same nature as cochineal, that is to say. it consists of the dried bodies of the female of certain scale insects, which are parasites of several species of oak, especially an oak of the Mediterranean region. They are round, about the size of a pea, and contain coloring matter analagous to carmine. Kermes is still used in Turkey, Morocco, etc; it is considered by most dyers to be the best of all red dyes; Kermes was in use in Europe in the tenth century and the old Gothic tapestries were dyed with it. These on comparison with the later,

28

Cochineal dyed tapestries prove its superiority both for shade and permanence.

Red from Kermes.

Mordant the wool(l lb)with 3 oz Alum and 2 oz Cream of Tartar, boiling it for two and a half hours. Take the wool out of the mordant, wring out gently, saturate with “sour-water” (i. e., water in which wheat bran has been allowed to ferment), put it into a bag and leave it in a cool place for five days, moistening it occasionally with the sour-water. Then dye in a bath of 10 oz Kermes in 2 gallons of water.

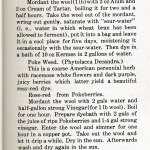

Poke Weed. (Phytolacca Decandra.)

This is a coarse American perennial herb with racemose white flowers and dark purple, juicy berries which latter yield a beautiful rosy-red dye.

Rose-red from Pokeberries.

Mordant the wool with 2 gals water and half-gallon strong Vinegar (for 1 Ib wool). Boil for one hour. Prepare dyebath with 2 gals of the juice of ripe Pokeberries and 1-4 gal strong vinegar. Enter the wool and simmer for one hour in a copper pot. Take out the wool and let it drip a while. Dry in the sun. Afterwards wash and dry again in the sun.

Sorrel. (Rumex Acedosa.)

A well known American wildflower. Its

29

roots and stalks yield a reddish dye.

Red from Sorrel.

Mordant the wool with Alum, 4 oz Alum in 2 gals water. Boil 1 Ib wool in the mordant for two hours. Transfer the wool to the copper dyepot, cover it with 2 gallons of water and to this add half a peck of well-washed Sorrel, roots or stalks, in sufficient amount to make a strong ooze. Boil slowly for one hour, take out the wool, rinse, and dry in the sun. This will give a pale red.

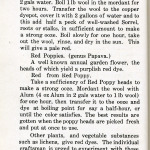

Red Poppies, (genus Papava.)

A well known annual garden flower, the heads of which yield a purplish red dye.

Red from Red Poppy.

Take a sufficiency of Red Poppy heads to make a strong ooze. Mordant the wool with Alum (4 oz Alum in 2 gals water to 1 Ib wool) for one hour, then transfer it to the ooze and dye at boiling point for say a half-hour, or until the color satisfies. The best results are gotten when the poppy heads are picked fresh and put at once to use.

Other plants, and vegetable substances such as lichens, give red dyes. The individual craftsman is urged to experiment with those whose names follow here, this list has been gotten from various sources, and there is a vast

30

field for research in trying out new mordants for many of them.

Birch. Fresh inner bark.

St. Johns Wort. Leaves

Wild Madder.

Red Root (Creanothus Am.).

Red Lobelia (L. Cardinalis).

Blood Root.

Red Oak. Bark.

Hemlock. Bark.

Potentil. Roots.

The Lichen, Ramalina Scopulorum.

The Lichen, Parmelia Omphalodes, or

“Black Crottle.” The Lichen, Lecanora Tartarea, or Crotal.

31

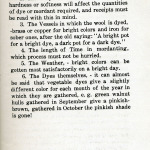

YELLOW

Nature has supplied us so liberally with material for the Yellow dye that we may well feel at a loss in making a choice. Hickory, Black Oak, and Crab-apple Barks; Sedge Grass and Cockle Burrs; Privet and Sweet Laurel Leaves; Marigold, Dye Flower, and Goldenrod, all yield up their store of golden sunshine when suitably treated in the dyepot.

They must all be subjected to the action of either Alum or acid of some kind to properly impart their essence to the material to be dyed, and just in proportion to the strength of the acid used in the mordant will be the fullness and richness of the resultant yellow tones.

Mathew Atkinson in his “Family Director, 1844” remarks “among all the materials affording the color Yellow there is perhaps none cheaper or better adapted to general use in dyeing than the Black Oak bark, as it imparts, when properly applied, every variety of shade, with all the richness of which the yellow dye is susceptible.”

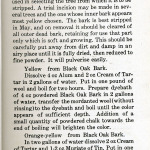

Black Oak Bark (Quercus nigra). A species of Oak native to North and Central America. The inner bark is the source of the dye, and, powdered, is sold as “Quercitron”, the active principle of this powder is a yellow, crystalline

32

substance Quercetin, which may be bought under the name “Flavine”. If it is desired to use the crude bark in dyeing some care should be used in selecting the tree from which it is to be stripped. A trial incision may be made in several trees and the one whose inner bark appears most yellow chosen. The bark is best stripped in May, and on removal it should be cleared of all outer dead bark, retaining for use that part only which is soft and growing. This should be carefully put away from dirt and damp in an airy place until it is fully dried, then reduced to fine powder. It will pulverize easily.

Yellow from Black Oak Bark.

Dissolve 4 oz Alum and 2 oz Cream of Tartar in 2 gallons of water. Put in one pound of wool and boil for two hours. Prepare dyebath of 4 oz powdered Black Oak Bark in 2 gallons of water, transfer the mordanted wool (without rinsing) to the dyebath and boil until the color appears of sufficient depth. Addition of a small quantity of powdered chalk towards the end of boiling will brighten the color.

Orange-yellow from Black Oak Bark.

In two gallons of water dissolve 2 oz Cream of Tartar and 1-2 oz Muriate of Tin. Pat in one pound of wool, cover the vessel and boil for one hour. Prepare dyebath of 4 oz powdered Black

33

Oak Bark in two gallons of water. Transfer the mordanted wool, without rinsing, and boil until the desired color is obtained.

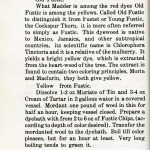

Old Fustic.

What Madder is among the red dyes Old Fustic is among the yellows. Called Old Fustic to distinguish it from Fustet or Young Fustic, the Cockspur Thorn, it is more often referred to simply as Fustic. This dyewood is native to Mexico, Jamaica, and other subtropical countries, its scientific name is Chlorophora Tinctoria and it is a relative of the mulberry. It yields a bright yellow dye, which is extracted from the heart-wood of the tree. The extract is found to contain two coloring principles, Morin and Maclurin, they both give yellow.

Yellow from Fustic.

Dissolve 1-2 oz Muriate of Tin and 3-4 oz Cream of Tartar in 2 gallons water in a covered vessel. Mordant one pound of wool in this for half an hour, keeping vessel closed. Prepare a dyebath with from 2 to 6 oz of Fustic Chips, (according to depth of color desired). Transfer the mordanted wool to the dyebath. Boil till color pleases, but for an hour at least. Very long boiling tends to green it.

Old Gold from Fustic.

Mordant 1 Ib wool in 2 gallons water with

34

1-2 oz Bichromate of Potash and 1-2 oz Cream of Tartar. Simmer for an hour. Prepare dyebath of from 2 to 6 oz of Fustic Chips in 2 gals water. Transfer the mordanted wool to the dyebath and boil till the shade desired is reached.

Lemon Yellow from Fustic.

Dissolve 4oz Alum and 1 oz Cream of Tartar in 2 gals water. Enter 1 Ib wool into this solution, simmer for 3 hours. Prepare dyebath of 4 to 6 oz Fustic Chips in 2 gals water. Boil for an hour to extract the dye, then enter mordanted wool and boil slowly for one hour.

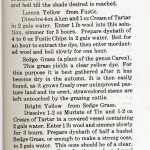

Sedge Grass (a plant of the genus Carex).

This grass yields a clear yellow dye. For this purpose it is best gathered after it has become dry in the autumn. It is then easily found, as it grows freely over unimproved pasture land and its erect, straw-colored stems are left untouched by the grazing cattle.

Bright Yellow from Sedge Grass.

Dissolve 1-2 oz Muriate of Tin and 1-2 oz Cream of Tartar in a covered vessel containing 2 gals water. Enter 1 Ib wool and simmer slowly for 3 hours. Prepare dyebath of half a bushel Sedge Grass, or enough to make a strong ooze, in 3 gals water. This ooze should be of a clear, brownish color. Transfer the mordanted wool to this dyebath and boil slowly for half an hour.

35

Golden Yellow from Sedge Grass.

Dissolve 4 oz of Alum and 1-4 oz Cream of Tartar in 2 gals water. In this mordant lib wool for 4 hours. Take vessel from fire and allow to cool without removing wool. Prepare dyebath of 3 or 4 gals water and enough Sedge Grass to make a strong ooze. After wool has become cold in the mordant transfer it to sedge-grass dye-bath, and simmer slowly until desired color is obtained; this is a beautiful and lasting dye.

Old Gold from Sedge Grass.

Mordant the wool, using 1-2 oz Bichromate of Potash to 1 Ib wool in 2 gals water. Simmer for one hour. Then transfer to a strong ooze, j prepared as before and simmer till the desired shade is reached. Rinse and hang in sun to dry; this applies to all Sedge Grass receipts.

Maize from Sedge Grass.

Mordant 1 Ib wool with 4 oz Alum and sufficient water. Prepare dyebath with 1-2 bu Sedge Grass. Enter mordanted wool; simmer twenty minutes, or until a straw-like shade is obtained.

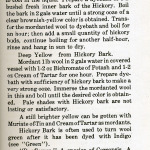

Hickory.

The bark of this well-known North American tree yields a yellow dye. The inner bark contains the coloring matter and may be used for dyeing at any time except spring, when the rising sap weakens its efficacy for that purpose.

36

Greenish-yellow from Hickory Bark.

For 1 Ib wool, dissolve 4 oz Alum in 2 gals water. Mordant for 4 hours, and allow the wool to cool in the liquid. Prepare a dyebath of 1-2 bushel fresh inner bark of the Hickory. Boil the bark in 2 gals water until a strong ooze of a clear brownish-yellow color is obtained. Transfer the mordanted wool to dyebath and boil for an hour; then add a small quantity of hickory buds, continue boiling for another half-hour, rinse and hang in sun to dry.

Deep Yellow from Hickory Bark.

Mordant 1 Ib wool in 2 gals water in covered vessel with 1-2 oz Bichromate of Potash and 1-2 oz Cream of Tartar for one hour. Prepare dye-bath with sufficiency of hickory bark to make a very strong ooze. Immerse the mordanted wool in this and boil until the desired color is obtained. Pale shades with Hickory bark are not lasting or satisfactory.

A still brighter yellow can be gotten with Muriate of Tin and Cream of Tartar as mordants.

Hickory Bark is often used to turn wool green after it has been dyed with Indigo (see “Green”).

“Dyeflower.” A species of Coreopsis. A small, wild flower growing freely on the hillsides in the Appalachians and adjacent country

37

side as far north as New Jersey. It blooms profusely all summer. An extract from the blossoms gives a most beautiful yellow dye.

Golden-yellow from Dyeflower.

Mordant 1 Ib wool with 4 oz Alum and 1 oz Cream of Tartar in 2 gals of water for an hour. Prepare a dyebath of 2 gals water into which a peck or so of dyeflower heads has been thrown. Transfer mordanted wool to the cool dyebath and raise temperature quickly to boiling point. Continue boiling till the desired color is gotten, remembering that too prolonged boiling will dull the color.

Brilliant Yellow from Dyeflower.

Dissolve 1-2 oz Muriate of Tin and 1-2 oz Cream of Tartar in 2 gals water. In this mordant 1 Ib wool for half an hour, keeping vessel covered mean while. Prepare dyebath of about a peck dyeflower heads in 2 gals water. Transfer mordanted wool without rinsing to the dyebath. Bring quickly to a boil and keep at boiling point until the desired color is obtained. Prolonged boiling will dull the shades.

Deep Yellow from Dyeflower.

Dissolve 1-2 oz Bichromate of Potash in 2 gallons water. Into this mordant put 1 Ib wool and boil for two hours being careful to keep the vessel covered. Prepare dyebath of one peck of dye-

38

flower heads in 2 gals water, put in mordanted wool, and boil for twenty minutes, stirring constantly, and airing the wool at intervals. Rinse and hang in the sun to dry.

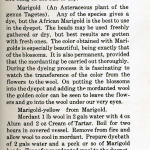

Marigold (An Asteraceous plant of the genus Tagetes). Any of the species gives a dye, but the African Marigold is the best to use in the dyepot. The heads may be used freshly gathered or dry, but best results are gotten with fresh ones. The color obtained with Marigolds is especially beautiful, being exactly that of the blossoms. It is also permanent, provided that the mordanting be carried out thoroughly. During the dyeing process it is fascinating to watch the transference of the color from the flowers to the wool. On putting the blossoms into the dyepot and adding the mordanted wool the golden color can be seen to leave the flowers and go into the wool under our very eyes.

Marigold-yellow from Marigold.

Mordant 1 Ib wool in 2 gals water with 4 oz Alum and 2 oz Cream of Tartar. Boil for two hours in covered vessel. Remove from fire and allow wool to cool in mordant. Prepare dyebath of 2 gals water and a peck or so of Marigold heads. Transfer mordanted wool to the dyepot, which has been raised to the boiling point. Stir constantly and air wool at interval. Continue

39

only so long as necessary to get the desired color. Remove from dye bath and dry in sun without rinsing. Later, rinse and again dry in the sun.

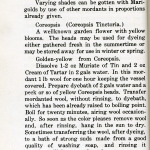

Varying shades can be gotten with Marigolds by use of other mordants in proportions already given.

Coreopsis (Coreopsis Tinctoria.)

A well known garden flower with yellow blooms. The heads may be used for dyeing either gathered fresh in the summertime or may be stored away for use in winter or spring.

Golden-yellow from Coreopsis.

Dissolve 1-2 oz Muriate of Tin and 2 03 Cream of Tartar in 2 gals water. In this mordant 1 Ib wool for one hour keeping the vessel covered. Prepare dyebath of 2 gals water and a peck or so of yellow Coreopsis heads. Transfer mordanted wool, without rinsing, to dyebath, which has been already raised to boiling point. Boil for twenty minutes, airing wool occasionally. So soon as the color pleases remove wool and, after rinsing, hang in the sun to dry. Sometimes transferring the wool, after dyeing, to a bath of strong suds made from a good quality of washing soap, and rinsing it therein, will improve the color.

Various shades can be gotten with Coreopsis

4O

by the use of other mordants, in the proportions already given.

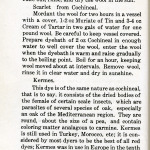

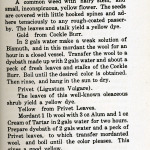

Cockle Burr, or Agrimony.

A common weed with hairy stem, and small, inconspicuous, yellow flower. The seeds are covered with little hooked spines and adhere tenaciously to any rough-coated passerby. The leaves and stalk yield a yellow dye.

Gold from Cockle Burr.

In 2 gals water make a weak solution of Bismuth, and in this mordant the wool for an hour in a closed vessel. Transfer the wool to a dyebath made up with 2 gals water and about a peck of fresh leaves and stalks of the Cockle Burr. Boil until the desired color is obtained. Then rinse, and hang in the sun to dry.

Privet (Ligustum Vulgare).

The leaves of this well-known oleaceous shrub yield a yellow dye.

Yellow from Privet Leaves.

Mordant 1 Ib wool with 3 oz Alum and 1 oz Cream of Tartar in 2 gals water for two hours. Prepare dyebath of 2 gals water and a peck of Privet leaves, to which transfer mordanted wool, and boil until the color pleases. This gives a good yellow.

Golden-Rod (Solidago).

There are many varieties of golden-rod,

41

dye may be gotten from the variety known as Dyers Weed,or Grey Golden-rod (S.Nemoralis). Mordant 1 Ib wool with 4 oz Alum and 2 oz Cream of Tartar in 2 gals water, boil for an hour, take out the wool and hang in a bag in a cool place. Keep it so for ten days, dampening it occasionally with the mordant. Then prepare a dyebath of 2 gals water in which a peck or so of the heads and tender stalks of Golden-rod have been boiled until a good strong ooze is extracted. Immerse the mordanted wool and boil till the desired color is obtained. This gives a good, lively yellow.

Osage Orange (Toxylon Pomiferum).

An ornamental American moreaceous tree, allied to the Mulberry. It was first found in the country of the Osage Indians, who employed its wood to make bows and arrows, as well as to dye their war bonnets, etc. The tree bears a yellow, apple-shaped fruit; it grows in south Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas, and attains a height of 50 feet with a diameter of 2 feet. In the South-West an extract of the roots and bark is made by boiling, and used as a dye. Like Fustic, the heart wood contains two coloring principles, Morin and Maclurin, and it has been urged that it be substituted for the former wood for dyeing purposes; it is claimed to be a

42

faster dye than Fustic, cheaper, and a native product instead of an import.

Osage Orange extract is marketed under the name “Aurantine”. For its use to produce various Yellow shades, the receipts given under Fustic may be followed.

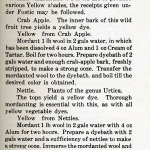

Crab Apple. The inner bark of this wild fruit tree yields a yellow dye.

Yellow from Crab Apple.

Mordant 1 Ib wool in 2 gals water, in which has been dissolved 4 oz Alum and 1 oz Cream of Tartar. Boil for two hours. Prepare dyebath of 2 gals water and enough crab-apple bark, freshly stripped, to make a strong ooze. Transfer the mordanted wool to the dyebath, and boil till the desired color is obtained.

Nettle. Plants of the genus Urtica.

The tops yield a yellow dye. Thorough mordanting is essential with this, as with all yellow vegetable dyes.

Yellow from Nettles.

Mordant 1 Ib wool in 2 gals water with 4 oz Alum for two hours. Prepare a dyebath with 2 gals water and a sufficiency of nettles to make a strong ooze. Immerse the mordanted wool and boil until the desired shade is obtained.

Sweet Leaf, Horse Sugar, or Dye Bush. (Symplocus Tinctoria.) In early spring the

43

bush of this name has clusters of intensely yellow, fragrant flowers on the bare twigs, except in the deep South, where the leaves remain on the tree all winter. These leaves are yellow-green, bright, and have a silvery sheen. If dried the color becomes more intense. The leaves are used to make a yellow dye. Yellow from Dye Bush. Mordant 1 Ib wool with 1-2 oz Muriate of Tin and 2 oz Cream of Tartar in a covered vessel for an hour. Have ready a peck of Dye Bush leaves, and 2 gals of boiling water in the dyepot. Transfer mordanted wool to the dyepot and add thereto the leaves. Boil for three-quarters of an hour. Remove, rinse, and hang in sun to dry.

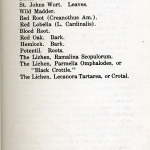

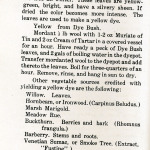

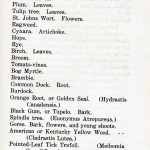

Other vegetable sources credited with yielding a yellow dye are the following:

Willow. Leaves.

Hornbeam, or Ironwood. (Carpinus Beludus.)

Marsh Marigold.

Meadow Rue.

Buckthorn. Berries and bark (Rhomnus frangula.)

Barberry. Stems and roots.

Venetian Sumac, or Smoke Tree. (Extract, “Fustine”.)

American Smoke Tree, or Chittam Wood.

Clematis. Leaves and branches.

44

Ash. Fresh inner bark.

Sundew. (Drosera Rotundifolia.)

Lombardy Poplar. Leaves.

Pear. Leaves.

Plum. Leaves. .:

Tulip tree. Leaves.

St. Johns Wort. Flowers.

Ragweed.

Cynara. Artichoke.

Hops.

Rye.

Birch. Leaves.

Broom.

Tomato-vines.

Bog Myrtle.

Bramble.

Common Dock. Root.

Burdock.

Orange Root, or Golden Seal. (Hydrastis

Canadensis.)

Black Gum, or Tupelo. Bark. Spindle tree. (Euonymus Atropureus.) Gorse. Bark, flowers, and young shoots. American or Kentucky Yellow Wood.

(Cladrastis Lutea.) Pointed-Leaf Tick Trefoil. (Meibomia Grandiflora.)

45

BLUE

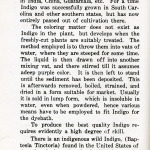

Indigo. This dye is the product of the plant Indigofera Tinctora, largely cultivated in India, China, Guatamala, etc. For a time Indigo was successfully grown in South Carolina and other southern states, but has now entirely passed out of cultivation there.

The coloring matter does not exist as Indigo in the plant, but develops when the freshly-cut plants are suitably treated. The method employed is to throw them into vats of water, where they are steeped for some time. The liquid is then drawn off into another mixing vat, and there stirred till it assumes a deep purple color. It is then left to stand until the sediment has been deposited. This is afterwards removed, boiled, strained, and dried in a form suitable for market. Usually it is sold in lump form, which is insoluble in water, even when powdered, hence various means have to be employed to fit Indigo for the dyebath.

To produce the best quality Indigo requires evidently a high degree of skill.

There is an indigenous wild Indigo, (Baptesia Tinctoria) found in the United States of America. It is a smooth, slender plant, with deep grey-green leaves and small, pea-like

46

blossoms of pure yellow. This plant is to be found in great abundance along the sides of the Appalachian Mountains; it may be recognized by the peculiar property of its leaves, which turn black on withering.

Preparation of dye material from Baptesia Tinctoria.

The Oldtime way of obtaining coloring matter from the Wild Indigo was as follows: Pack the plant in a barrel and pour water over it. Leave it to ferment, which it will probably do in a couple of days, then squeeze out the plant and churn the liquor, then add lye from oak-wood ashes until precipitation of dye occurs. To help this result, bruise and soak some Red Sumac, and add the liquid from this to the extract. When this becomes clear pour off the fluid and the dye material will be found as sediment in the barrel.

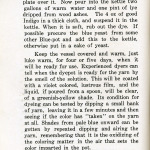

To prepare Indigo for dyeing, three methods may be given: First, the old-fashioned Indigo vat; second, Indigo Extract (Saxon Blue); and last, the Soda-hydrosulphite vat. For setting up the Indigo vat, or Blue Pot, many receipts exist. From these I have chosen a mountain dyer’s as follows: Place an iron kettle, capable of holding at least five gallons, where it can be kept warm for several days, as

47

on the hearthstone. Mix a pint of Madder with a pint of wheat-bran, just moisten this, then put it at the bottom of the kettle with a china plate over it. Now pour into the kettle two gallons of warm water and one pint of lye dripped from wood ashes. Tie 4 oz of good Indigo in a thick cloth, and suspend it in the kettle. When it is soft, rub out the dye. If possible procure the blue yeast from some other Blue-pot and add this to the kettle, otherwise put in a cake of yeast.

Keep the vessel covered and warm, just lukewarm, for four or five days, when it will be ready for use. Experienced dyers can tell when the dyepot is ready for the yarn by the smell of the solution. This will be coated with a violet colored, lustrous film, and the liquid, if poured from a spoon, will be clear, of a greenish-yellow shade. Its condition for dyeing can be tested by dipping a small hank of yarn, leaving it in a few minutes and then seeing if the color has “taken” on the yarn at all. Shades from pale blue onward can be gotten by repeated dipping and airing the yarn, remembering that it is the oxidizing of the coloring matter in the air that sets the color imparted in the pot.

For very dark blues it may be needful to

48

leave the yarn in the pot for several hours, then air without rinsing for a like period. The yarn should of course be thoroughly washed when the right shade has been reached.

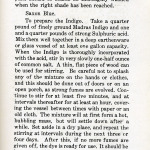

Saxon Blue.

To prepare the Indigo. Take a quarter pound of finely ground Madras Indigo and one and a quarter pounds of strong Sulphuric acid. Mix them well together in a deep earthenware or glass vessel of at least one gallon capacity. When the Indigo is thoroughly incorporated with the acid, stir in very slowly one-half ounce of common salt. A thin, flat piece of wood can be used for stirring. Be careful not to splash any of the mixture on the hands or clothes, and this should be done out of doors or on an open porch, as strong fumes are evolved. Continue to stir for at least five minutes, and at intervals thereafter for at least an hour, covering the vessel between times with paper or an old cloth. The mixture will at first form a hot, bubbling mass, bat will settle down after a while. Set aside in a dry place, and repeat the stirring at intervals during the next three or four days. After this, if no more fumes are given off, the dye is ready for use. It should be kept covered, and stored in a dry cupboard, otherwise it will absorb moisture from the air,

49

and become weaker.

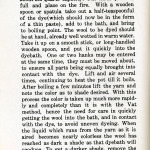

To Dye, Use a brass or enamel pot of about six quarts capacity. Fill three-quarters full and place on the fire. With a wooden spoon or spatula take out a half-teaspoonful of the dye (which should now be in the form of a thin paste), add to the bath, and bring to boiling point. The wool to be dyed should be at hand, already well-wetted in warm water. Take it up on a smooth stick, or long-handled wooden spoon, and put it quickly into the dyebath. One or two hanks may be entered at the same time, they must be moved about, to ensure all parts being equally brought into contact with the dye. Lift and air several times, continuing to heat the pot till it boils. After boiling a few minutes lift the yarn and note the color as to shade desired. With this process the color is taken up much more rapidly and completely than it is with the Vat method, hence the need for care in quickly getting the wool into the bath, and in contact with the dye, to avoid uneven dyeing. When the liquid which runs from the yarn as it is aired becomes nearly colorless the wool has reached as dark a shade as that dyebath will produce. To get a darker shade, remove the wool from dye bath whilst adding more dye,

50

stir this in well and quickly re-enter the yarn; this will ensure an even color, free from streaks or light patches. When the yarn is as dark as wanted, continue to boil for fifteen minutes. Rinse thoroughly. A little Bicarbonate of Soda in the washing water towards the last will neutralize any remaining acid in the wool.

Hydrosulphite-Soda Vat. This method is the most modern way of dyeing with Indigo, it can be used either with the natural or synthetic product. It produces a pleasing and fast blue. All shades, from light to dark blue, can be gotten by varying the length of time and number of dips that the wool is given in the dye vat. It does require care in mixing and testing the solutions used, but, given reasonable care, results can be depended on. The ingredients are:

1 oz powdered Indigo.

1 oz Hydrosulphite of Soda.

1 & 1-2 oz Caustic Soda (Sodium Hydroxite). Apparatus needed consists of a glass measuring vessel, graduated in ounces. A glass stirring rod. A Hydrometer, such as is used for testing electric storage batteries. A pasteurizing thermometer.

51

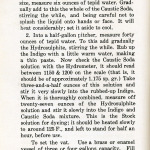

To make the Stock Solution we must make two preliminary solutions.

- Into a glass or enamel vessel of sufficient size, measure six ounces of tepid water. Gradually add to this the whole of the Caustic Soda, stirring the while, and being careful not to splash the liquid onto hands or face. It will heat considerably; set it aside to cool.

- Into a half-gallon pitcher, measure forty ounces of tepid water. To this add gradually the Hydrosulphite, stirring the while. Rub up the Indigo with a little warm water, making a thin paste. Now check the Caustic Soda solution with the Hydrometer, it should read between 1150 & 1200 on the scale (that is, it should be of approximately 1.175 sp. gr.) Take three-and-a-half ounces of this solution and stir it very slowly into the rubbed-up Indigo. When it is thoroughly combined, measure off twenty-seven ounces of the Hydrosulphite solution and stir it slowly into the Indigo and Caustic Soda mixture. This is the Stock solution for dyeing; it should be heated slowly to around 125 P., and left to stand for half an hour, before use.

To set the vat. Use a brass or enamel vessel of three or four gallons capacity. Fill three-quarters full of water at 125 deg. F.

52

Add to this three or four ounces of Solution No. 2 – this is to de-oxygenate the bath. Let it stand for a quarter hour. Meanwhile check the Stock Solution for correct condition, as follows: Dip the glass stirring- rod and withdraw it. The liquid on it should be a clear greenish yellow, changing quickly to blue. If the glass is covered as it is withdrawn with blue patches, these indicate undissolved Indigo, and call for addition of more of the No.2 solution (Hydrosulphite) – say two ounces.

On the other hand, a thick, milky appearance of the stock solution calls for the addition of a little caustic soda solution. In either case, if correction is needed, give the added chemical time to function. However, given care in the first mixing and measuring, the stock solution will probably need no additions.

To Dye. Measure off an ounce of the stock solution and stir it into the dyebath, take care not to make many bubbles in so doing. Set the dye pot over low heat and bring to 125 deg. F. Enter the wool, previously wetted, move it around at intervals. After some minutes lift the wool and note the color. It should be a yellowish-green, changing on exposure to blue. Continue dyeing for fifteen minutes, then lift and air for the same length of time. If not

53

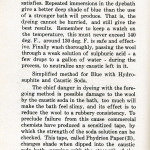

dark enough, replace the wool in the dyebath, first adding a little stock solution, and repeat the alternate dyeing and airing until the color satisfies. Repeated immersions in the dyebath give a better deep shade of blue than the use of a stronger bath will produce. That is, the dyeing cannot be hurried, and still give the best results. Remember to keep a watch on the temperature, this must never exceed 140 deg. F., around 130 deg. F. is safe and effective. Finally wash thoroughly, passing the wool through a weak solution of sulphuric acid – a few drops to a gallon of water – during the process, to neutralize any caustic left in it.

Simplified method for Blue with Hydro-suphite and Caustic Soda.

The chief danger in dyeing with the foregoing method is possible damage to the wool by the caustic soda in the bath, too much will make the bath feel slimy, and its effect is to reduce the wool to a rubbery consistency. To preclude failure from this cause commercial chemists have produced a sensitized tape, by which the strength of the soda solution can be checked. This tape, called Phydrion Paper (B), changes shade when dipped into the caustic soda bath, varying with the strength of the solution, and its color can be compared to a

54

scale shown on the little box in which the tape is put up. The tape can be obtained from the Scientific Glass Apparatus Corporation of Bloomfield, New Jersey.

To dye by this method, first boil up three to five gallons of water in the dyepot. Continue boiling for half an hour, to drive off all air held in suspension, then let the water cool to 120 deg. F. Now slowly stir in caustic soda, a little at a time, dipping fragments of the test tape at intervals, and comparing the shade to the tints of the scale. When the reading is between 7 & 9 the strength is correct. Now weigh out equal amounts of Indigo and Hydro-sulphite, say one-half ounce of each. Rub the powdered Indigo up with a little water, to make it mix easily and stir it into the caustic soda bath. Then gradually stir in the Hydro-sulphite; let stand ten minutes, gradually warming the bath to 125 deg. F. – not over 140 F. Enter the wool, dye according to directions already given for alternate dyeing and airing, etc. After washing, and an acid bath to remove any remaining caustic soda, pass through a very hot soapsud solution, using a mild soap, such as Ivory flakes for this, then rinse and hang out to dry.

The resulting color by this method is a

55

very beautiful blue, and, because of its fastness, it should always be employed when it constitutes the first step towards producing green shades. In my opinion, however, it does not entirely supersede the Saxon Blue method, as the shades of blue gotten by that process have an unique charm of their own.

Slate Blue from Logwood.

Mordant one pound of wool in a covered vessel with half an ounce of Bichromate of Potash, dissolved in sufficient water. Boil for an hour, remove and rinse. While the wool is mordanting make a strong ooze with Logwood chips in three gallons of water; strain out the chips and add one-half ounce chalk. Enter the mordanted wool and boil for an hour, at intervals raising and airing the wool. Then wash and hang out to dry.

56

GREEN

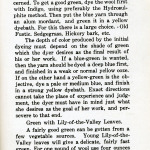

Green is perhaps the least satisfactory of all vegetable dyes, so far as fastness is concerned. To get a good green, dye the wool first with Indigo, using preferably the Hydrosulphite method. Then put the blue yarn through an alum mordant, and green it in a yellow dyebath. For this there is a large choice, – Old Fustic, Sedgegrass, Hickory bark, etc.

The depth of color produced by the initial dyeing must depend on the shade of green which the dyer desires as the final result of his or her work. If a blue-green is wanted, then the yarn should be dyed a deep blue first, and finished in a weak or normal yellow ooze. If on the other hand a yellow-green is the objective, dye a pale or medium blue, and finish in a strong yellow dyebath. Exact directions cannot take the place of experience and judgment, the dyer must have in mind just what she desires as the goal of her work, and persevere to that end.

Green with Lily-of-the-Valley Leaves.

A fairly good green can be gotten from a few vegetable sources. Young Lily-of-the-Valley leaves will give a delicate, fairly fast green. For one pound of wool use four ounces of Alum, and mordant for an hour. Prepare

57

the dyebath with a peck of young Lily-of-the-Valley leaves, boiling them until they have colored the ooze. Transfer the wool to the dyebath, without rinsing, and boil for an hour.

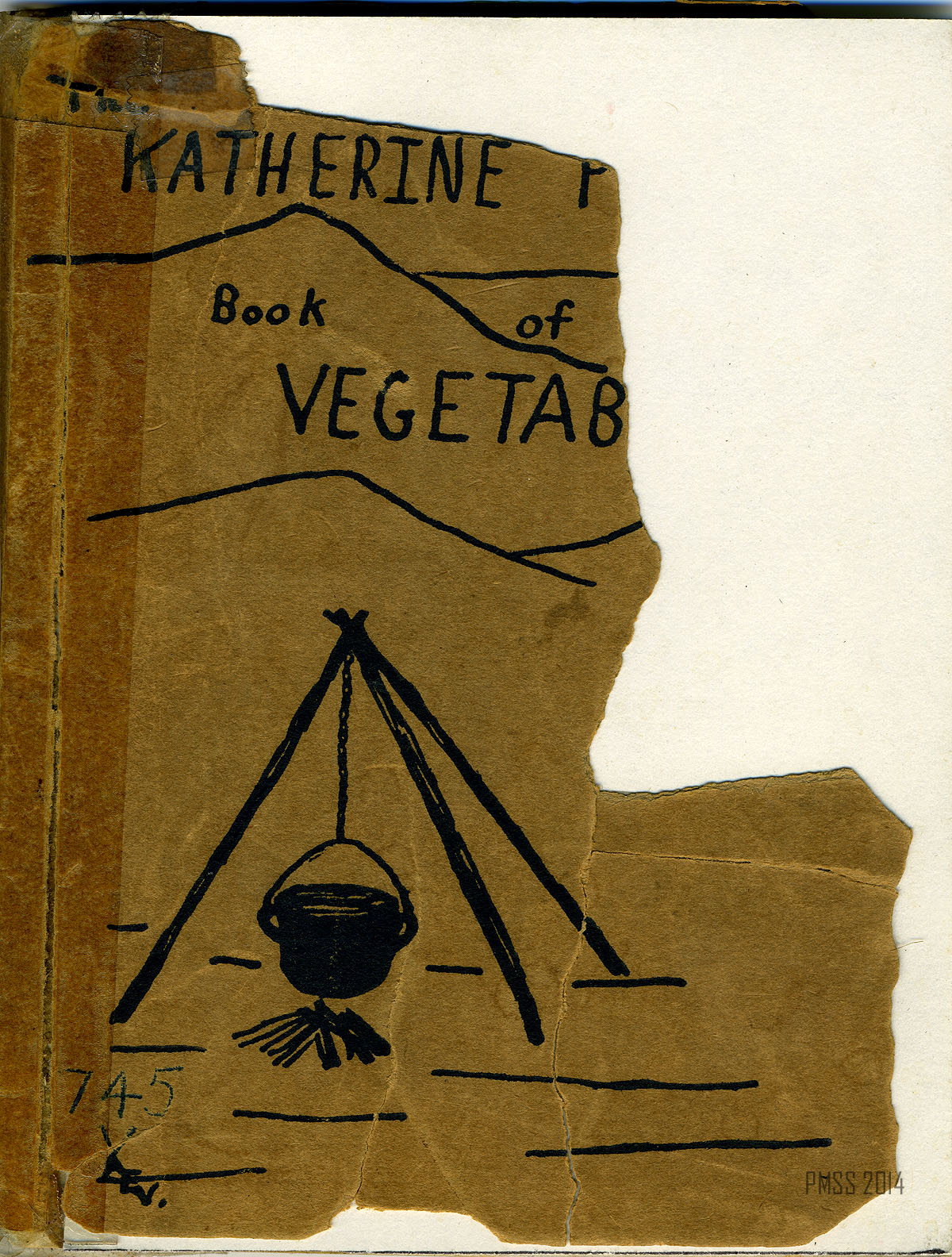

Bottle-Green with Logwood.

Mordant one pound of wool in a covered vessel with one-half ounce of Bichromate of Potash for an hour. Remove and rinse.

Prepare a strong ooze with Logwood chips in three gallons of water. Strain out the chips and add one-half ounce chalk to the ooze. Enter the mordanted wool and boil for an hour, lifting and airing it at intervals. The resulting color should be a dark slaty blue. Rinse and transfer to a dyebath of Old Fustic. For this, make up a strong ooze, either by boiling Old Fustic chips, or dissolving the prepared crystals. Use a part of this to form the dyebath, of medium strength; enter the dyed wool and boil for ten minutes; lift, air, and rinse. Examine in the light for color. If not satisfactory, add some of the Old Fustic ooze to the dye-bath, return the wool and boil again. Continue this process till the color pleases. Boiling time in the Old Fustic bath should total at least one-half hour.

58

BROWN

The most dependable source of our brown dye is the Black Walnut, and wherever that tree flourishes the dyer will look to it for most of the shades of brown which he or she has need for. Bark, roots, and the hulls protecting the nuts are alike rich in the dyeing material, but, since the black walnut is a valuable tree, we shall not consider the use of either bark or roots, for equally good results can be obtained from the hulls, an annual waste product at the time of harvesting the nuts.

Brown from Walnut Hulls.

This is a substantive dye, and needs no mordant. Boil up half a peck of hulls in three gallons of water, in an iron pot. Enter the wool, moving it round till it is all equally wetted by the dye, and boil for a length of time depending on the depth of color desired. For a pale tan boil for a few minutes only; for darker shades continue boiling for from ten minutes to an hour or more. This gives a warm, rich brown, fast to light and washing.

To get a very dark brown add a pinch of copperas and a double handful of sumac berries. Simmer the wool in this for an hour or more and leave it in the ooze overnight. Then rinse very thoroughly, both the wool and the

59

dyepot before it is used for other work.

A pinkish brown can be gotten from the green hulls, when they are first stripped from the nuts in the Fall. Hulls for later use must be spread out and dried thoroughly before being bagged and hung up for use throughout the year.

Brown from Sumac.

Another shade of brown can be gotten with sumac berries alone, gathered after they have turned red and boiled up in a brass or enamel pot. This also is a pleasing shade of brown, with a greenish tinge, and very fast. All depths of color, from tan to dark brown, can be gotten, depending on strength of ooze and length of time for which the wool is boiled therein.

Brown from Black Walnut Leaves.

In the fall a delicate shade of brown can be gotten as follows: Gather a peck of Black Walnut leaves. Having cleaned the pot thoroughly put a layer of these leaves in the bottom, then a layer of wool yarn on these, then another layer of leaves, and so on alternately. Pour in enough “fair water” to cover all. Then cover the pot and set aside for about a week, after which time remove and rinse the yarn. It will be found dyed a pleasing light shade of brown.

60

BLACK

A good black can be gotten from Walnut (either hulls, bark, or root) in combination with Sumac. White Walnut gives the best results.

Use the hulls to make a strong ooze, as when dyeing brown, but put in a larger quantity in your iron pot, with three or four gallons of water. Start a brisk fire under the pot and when it boils add a double handful of sumac berries and a tablespoonful of copperas. So soon as the last is dissolved enter the wool. Simmer over a slow fire all day. Leave overnight in the dyepot and continue simmering next day. The process should go on for at least twenty-four hours in all. At the end of that time let the fire die out, but leave the yarn in the dyepot until it has become cold. Then remove and rinse the wool thoroughly. If the black is not sufficiently intense, make up a fresh ooze and repeat the process as detailed. Perseverance will produce a satisfactory black.

A quicker method of producing a good and lasting black is by the double-dye method, using Indigo and Walnut. This was the way favored by William Morris, who toward the end of the last century did so much to keep

61

handicrafts alive in England, when the industrial revolution threatened their extinction.

Black with Indigo and Walnut.

Dye the wool first a deep blue, either by the Blue-pot or the Hydrosulphite method. Rinse the blue yarn very thoroughly and then transfer it to a dyebath containing a strong ooze already prepared from walnut hulls, reinforced by a double handful of sumac berries. In this dyebath boil the blue yarn for an hour or longer, then set aside overnight to cool.

Next day take out the yarn, rinse well and examine in strong daylight. If the color is a decided blue-black return to the walnut dye-bath, add some more walnut hulls, and repeat boiling, with addition of a pinch of copperas. Let the wool simmer for an hour or so, then remove the dyepot from the fire and set aside to cool. When it has become cold remove the yarn, rinse well and dry.

62

Here in this little book we have put down a few receipts for dyeing wool. From this small beginning the real dyer can go forward and have a grand time experimenting, and get his own palette of colors with which to work. Some will last forever, and some will fade gradually; the deeper and richer the shade the more permanent the color always.

Not everyone is a dyer; some have success and some do not, but any one will have an interesting time. For the colors Blue and Rose, Indigo and Madder are the best. But for the other colors the woods, the flower-gardens are ours to experiment with. There is dye in roots, barks, flowers, hulls, leaves, and lichens, and many of these dyes have never been discovered, nor the mordants with which they are made fast. The dyer who has a real love of color and much patience can work all this out for himself. We hope this book will just be a beginning, and that you will go ahead and find many more lovely colors. Anyway we know that is what Miss Pettit would wish!

63

[Back cover]

SEE ALSO:

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH Weaving at PMSS Beginnings

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH Weaving at PMSS 1930s -1940s

HELEN WILMER STONE VINER Staff – Biography

KATHERINE PETTIT Director – Biography

USDA Home Dyeing with Natural Dyes 1935 Booklet