Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 04: ADMINISTRATION – Directors

Series 15: ARTS AND CRAFTS

Series 37: WEAVING AT PMSS

Katherine Pettit

Weaving at PMSS

Beginnings

Girl’s Industrial (Draper Building). Interior view of weaving room with looms. [II_6_swimming_draper_boys_262.jpg]

KATHERINE PETTIT Weaving at PMSS Beginnings

One might say that Pine Mountain Settlement School was conceived among coverlets. Weaving at the School certainly was encouraged by the re-discovery of the craft of coverlet weaving and the enthusiastic collecting of mountain weaving near the turn of the last century. Katherine Pettit, founder of Pine Mountain Settlement School and earlier of Hindman Settlement School, was an avid collector of “kivers.” Her interest in the exquisite craft of coverlet weaving kept her roaming the mountains in the early years of the twentieth century in search of new patterns and techniques. It was the search for beautiful mountain “kivers” that brought Pettit journeying across the Eastern Kentucky region and eventually to the Pine Mountain valley in Harlan County, Kentucky. There, in the long valley on the north side of the Pine Mountain, she established one of the most unique of the Appalachian rural settlement schools.

THE SEARCH FOR COVERLETS

Pettit began her search for coverlets when she was at Hindman in Knott county where, with May Stone, she had established a rural settlement school. Her work there established her first major contacts with the people of Eastern Kentucky’s counties, particularly Perry, Leslie, Letcher, Knott, and Harlan. Even before the founding of Hindman, in 1901, Pettit was into her third summer season in the eastern Kentucky mountains at a location known as “Sassafras.” She and her adventuresome colleagues came to the area and set up a camp, first at Hazard (Camp Cedar Grove) where they offered summer educational programs. And, later at Sassafras. She and her colleagues often journeyed by horseback to many of the remote valleys and hollows of nearby Harlan, Perry and Letcher counties to familiarize themselves with the people and frequently she came into contact with mountain weavers. She soon became enchanted by the mountain craft and began to search for coverlets to purchase. She also found her interest in the craft gave her a sound introduction to the people and to mountain living and families. What she learned in these horse-back journeys, created a life-long commitment to the region and its needs.

While looking for homespun coverlets she discovered more than the coverlet. She discovered the weavers and their humble but rich skills, their ancient culture, and their stoic resourcefulness. She talked to the subsistence farmers who raised flax for weaving and sheep for shearing. She watched as women dyed, carded and spun wool and flax. Theirs was a life-style that she would soon come to cherish, partially adopt but commit to “raising up.”

“Grannie Creech ?” Weaving. [Vl_35_1127a.jpg]

FOUNDING OF THE PINE MOUNTAIN SETTLEMENT SCHOOL

Soon overwhelmed by the rapid industrialization of the region near Hindman and the many negative impacts the railroad brought into the region, Pettit turned her sights to the more remote areas of eastern Kentucky. In Harlan county she found the distance from the rapidly industrializing world she desired and a community that was receptive to the educational ideas she had explored in her Hindman Settlement School experiences. She rapidly reached out to her many contacts in the Blue Grass, to women’s clubs in Kentucky and the Northeast and to the many friends she had made at Hindman. At Pine Mountain she soon established a rustic home and began the process of building another settlement school dedicated to serving the people of the remote Pine Mountain valley and nearby hollows. Her retreat to the more remote location did not, however, indicate that she become a recluse.

When she came to Pine Mountain in 1913, she sought the help of William Creech and the families living in the surrounding valley. She also brought Ethel de Long from Hindman as a co-founder and director of educational programs and the two established a school founded on the principles of the more urban settlement houses found in Chicago, New York, Boston and their experience at Hindman. Pettit and de Long recruited educators and workers from the urban settlement schools and women’s colleges and sowed the seeds for a remarkably progressive educational program.

What grew in the long Pine Mountain valley was a settlement school that adopted a unique response to the urban settlement house ethos. Weaving was central to that ethos. While weaving in the urban settlements often depended on teaching weaving that was modeled on practices found in the Arts and Craft’s Movement and in Scandinavian models, Pettit’s models for instruction were taken directly from the surrounding community. Her models were already established in the mountains of Kentucky and other areas of the Southern Appalachians and the origins were clearly much older and more unique than the popular models of the Arts and Crafts Movement and the Scandinavian models. Weaving for Pettit and for the Pine Mountain community was an integral part of the region’s life. It was a response to the legacy of the many mountain families whose lives still had strong roots in pioneering and subsistence farming reminiscent of the earliest settlers of the region. The weaving carried their memory of the life of their ancestors in Scotland, England, Ireland, France, Germany and other European countries as did their tools and their practice. The demands of a rural environment had kept alive many of the traditional cultural skills in the households of many families in the Pine Mountain valley and surrounding region. Pettit recognized this gift on her doorstep but was soon challenged by the mandate to keep the cultural heritage alive but to combine it with a viable economic program for “raising-up” a people who were still in a pioneering and subsistence mode.

WEAVING AND FARMING

Farming was another foundational principle Pettit integrated into the new School’s core mission. Weaving and farming go together well and well they served Pine Mountain Settlement and its community for many years. From “Uncle” William Creech, the generous donor of land for the School, Pettit learned about the hard-scrabble work of flax farming. From “Aunt” Sal, his wife, she learned about local wool processing practice. Her staff and early students became active participants in both the farming practice and the weaving practice of local families. The School shared labor with the community and. more importantly, shared knowledge.

Pettit’s interest and promotion of weaving pre-dates the important work of Eliza Calver Hall and her 1912, A Book of Hand-Woven Coverlets. No doubt Pettit was strongly influenced by Hall’s book, which she owned, and later the work of the weaver Anna Ernberg who had assumed the position of superintendent of Fireside Industries at Berea College, Kentucky in 1911, but she was embedded in the idea of weaving and settlement-work much earlier. She had deep connections with other women who helped shape mountain weaving into cottage industries and economic models for Appalachian craft.

Pettit made the Pine Mountain valley and the Settlement School her home and along with Ethel de Long, whom she had recruited away from Hindman Settlement School, she proceeded to build her school. Pettit’s interests were with the “hands-on” practices of the community, and de Long was masterful at implementing a robust educational program. Pine Mountain soon became one of the most unique and viable of the Southern Appalachian rural settlement schools. Today the farm still produces food through the seasons and the sound of the batten, weaving away, has rarely ceased its tempo.

CHANGE AND CHALLENGE

At Pine Mountain Pettit and her staff clearly loved and hated the isolation of the mountains but Pettit challenged her staff and the people of the region to look beyond the walls of mountains surrounding their valley. She challenged them to carefully evaluate the flood of ideas, economies, and beliefs that could prepare the people of the region for the inevitable changes coming to the mountains. Following the turn of the century industrialization was moving ever closer to the Pine Mountain valley. For a time a small railroad ran right through the center of the School and carried timber from the surrounding mountains to mills across the steep Pine Mountain. Pettit was not successful in stopping the movement of timber across the School land but tolerated the short-term contract. As the rapid and rapacious appetite for forest and mineral grew, Pettit recognized the need to develop a marketing strategy for mountain crafts that would bring money into the area but would not destroy the environment, particularly the land held by the School. Weaving was part of her plan at “raising-up” the mountain people and she set about finding looms, building looms and establishing weaving as part of the School program.

100 YEARS OF HISTORY 1913-2013

Founded in 1913, Pine Mountain celebrated its 100th year of existence in 2013. Katherine Pettit retired from the School in 1936 but the School archive contains numerous directives, letters, invective, and suggestions that show her intense connection to the School until her death in 1938. The models of education, farming, health-care, and civic responsibility that Pettit and others at the School provided the people of this long valley in Eastern Kentucky and to the state, yielded a rich future while preserving the best of the earlier cultural legacy. Weaving at Pine Mountain has had a continuous association with the School since its founding and today it continues to inspire ideas and pride in it weavers and workers.

The beautiful homespun coverlets discovered by Pettit on her mountain rambles and which became a visual passion for Pettit and for others who saw them, gave birth to any number of creative ideas in the first several decades of Pine Mountain. It is impossible not to have a deep appreciation for the skill and artistry of the craft of weaving and for the women and men who wove the exquisite and complicated patterns found in Pettit’s collection of coverlets. Such skill and artistry signaled the rich potential of the people of the area. The mountain coverlet in all its complexity and subtle colors, has a deep and extended history in the lives of mountain families with a weft that stretches back to Ireland and to Scotland, to France and to England. The coverlet is a visual testimony to the people’s deep intelligence, creativity and manual skills, Often described as “asleep”, “apart”, “lazy”, “dull”, or worse, the early mountain weavers testify against these regional stereotypes. They produced some of the most elegant and complex and extensive repertoire of weaving found in the country. Their coverlets and Pettit and Pine Mountain all came together at just the right time and in the right place. The Pine Mountain archive has long been the keeper of much of the history of the exquisite legacy of weaving in the Kentucky mountains.

From THE KATHERINE PETTIT BOOK OF DYES that details vegetable dying, to implements that convey the tactile activity of the weaver’s art, to correspondence related to marketing of mountain craft, to the intimate stories of times spent in homes where weaving was done, — the archives at the School are rich in weaving lore and history.

THE BODLEY-BULLOCK COVERLET COLLECTION

Shortly before Katherine Pettit died she left some of her collection to Pine Mountain Settlement School and donated the remainder in May of 1936 to the Bradford Club of Lexington, Kentucky. Eventually the collections found their way into the holdings of Transylvania College by way of the historic home owned by the college, the Bodley-Bullock House on Gratz Park in Lexington. The Bullocks were Pettit’s relatives. Dr. Waller O. Bullock, Jr. had married Pettit’s younger sister, Minnie Barbee Pettit and in 1912 the couple moved into the house on Gratz Park. The home was obviously an active intellectual scene, filled with books and art, enjoyed by the patriarch, Waller O. Bullock, Jr. his wife and children. Bullock, Katherine Pettit’s brother-in-law, was a doctor and a sculptor. He knew well the education of joining head and hand and heart, and no doubt passed that along to his children. The home, located adjacent to one of Lexington’s most impressive parks, Gratz Park, is surrounded by the homes of other intellectual and Progressive elites and was a center of early cultural activity. Individuals such as Henry Clay, the early entrepreneur William Gratz, John Wesley Hunt, the first millionaire west of the Alleghenies, and others had enjoyed the many stately homes on the Park. Pettit often came to stay with the Bullocks and it was there in a small garden apartment that she died in 1936.

Many of Pettit’s coverlets and textile fragments in both the Pine Mountain collection and the Bodley-Bullock collection have histories that, in some cases, go back some 200 years. Some coverlets have well documented stories, and others have their provenance waiting to be discovered by researchers. But, all have a visual presence that cannot be denied and many carry names that suggest ties with life in the family, region, and early nation as well as hints of ancient balladry and dance in the British Isles. Many also suggest life on the farm and early pioneer days.

For example a beautiful peach and vanilla coverlet with a pattern called “Kentucky Winding Blades” in the Lexington collection, has the following attached note:

“This coverlet was made by Granny Stallard who was 110 years old when she died about 20 years ago [note:1936]. She sent this with a number of other coverlets and blankets with her great, great grandchildren to the Pine Mountain Settlement School to pay for their tuition. She said that most of these were made when she was in the ‘rise of her bloom’ — sixteen years old.”

Another textile, un-named, a very worn and modified blanket/shawl has a badly damaged note that reads:

“This shawl was willed to … Uncle Enoch Combs, when he was a young man, not quite 20. [When he was] starting [for war] his sweetheart Nancy St … him and gave him this shawl [to ….] him. She told him to f… [when the] war was over. This he [did ?] … Uncle Enoch wore the shawl [until he was] an old man with long white [hair].”

Even this fragmented note tells of a very precious warp that is woven with the weft of memories; love, and loss and return and loss, again. So many of the weavings of Appalachia have these stories. They speak to what Eliza Calvert Hall calls the “Time Spirit” in her important 1912 book, The Book of Handwoven Coverlets. [1] The “time spirit” is found in that object that cannot be handled without recalling the life of the past. Many of the names of the coverlets speak to the past times. Stories, such as “Young Lady’s Perplexiuty,” [sic] “Lonely Heart,” “Youth and Beauty,” “Catch Me If You Can,” and “Lasting Beauty.” “…Rise of her bloom” is a mountain colloquial reference to the early adolescence of girls as it was often in these early years that girls began to learn weaving and to assemble their household textiles for later marriage and home-building. It can quickly be deduced that coverlets were often seen as the dowry of young girls. Certainly they were the offerings that she carried into her marriage in her “Hope Chest.”

Eliza Calvert Hall has pointed out that the naming of coverlet patterns is a very imprecise practice. She says, ”… a design may have one name in North Carolina another in Kentucky, another in Tennessee, and still another in Virginia, as if it were a criminal fleeing from justice.” It is difficult to imagine a more comforting “criminal.”

THE SASSAFRAS ALBUM

Enoch Combs [the same as mentioned earlier] and his wife Mary were a childless couple who lived at Sassafras, near Hindman, Pettit’s first school location. The Combs’ were the hosts for a group of young women who came to the third and final summer camp at Sassafras in Knott county prior to the establishment of Hindman Settlement by Pettit and May Stone. Katherine Pettit, of Lexington; Mary E. McCartney, of Louisville; May Stone, of Louisville; and Rae M. McNab, also of Louisville, traveled into what had become familiar, but still, very rugged mountains of eastern Kentucky. Their summer school at Sassafras in 1901 was the last of a series of summer camps established to serve the literacy-poor hollows in Knott County. The success of these summer camps and the enthusiasm of Pettit and Stone led them to the foundation of a permanent school at Hindman in 1902, the following year.

The life of the Combs family and their skills at weaving were captured in a small album of photographs belonging to Katherine Pettit which she titled “The Social Settlement in the Ky [Kentucky] Mountains, Sassafras, Knott Co[unty]. 1901.” This small and fragile album of 27 pages, held in the Pine Mountain archive, is one of several copies that are found at UNC Chapel HIll and Berea. The album shows members of the Combs family and a young lady who was living with the Combs’, shearing their sheep, washing the wool, drying the wool, picking and carding, dying the “hanks”, and finally spinning the wool to be placed on spindles. The images freeze this valuable pioneer process in time and allow the viewer to understand the many complex tasks associated with the manufacture of textiles in the Southern Appalachians.

FLAX

The processing of wool is just one of the many complex tasks associated with Appalachian textiles. There is another even more arduous series of processes included in the processing of flax. When Katherine Pettit came to Pine Mountain she met “Aunt” Sally Creech. In Aunt Sal she had one of the finest weavers and spinners as an accomplice in her search for “kivers.” But, she also had a consummate teacher. Aunt Sal was the wife of William Creech, the farmer whose vision of a school caught the imagination of Pettit and whose land formed the basis of the physical site for the Pine Mountain Settlement School. Uncle William grew flax and harvested it to process linen thread. Katherine Pettit provided him with the seeds.

The elaborate process of flax reduction to thread was a hold-over from the Ulster-Scot origins of many of the people of the Southern Appalachians. Ulster, in Ireland, had long been a center of linen production in Europe. Flax farming was still a viable occupation for the many Scots-Irish-English-French-Cherokee-German and African-American families who lived deep in the Appalachian mountains. At Pine Mountain, farmers who maintained subsistence farms in the small valley and on the steep slopes near the School sometimes found ways to extend their incomes. Flax was one of the crops that could be turned to income. But, few of these resourceful farmers remained at the turn of the twentieth-century.

When Pettit arrived in the valley she met families with names like Creech, Boggs, Turner, Couch, Combs, Coots, Day, Hall, and more, suggesting that the population was heavily indebted to England, Ireland and France in its origins. A study of family names could shed light on possible English or Irish or Scotch origins of textile practice, but unlike tracing ballads or dances, or pageants, the trail for textile arts is not well-developed and families migrated to all areas of the British Isles. Yet, the production of linen thread, an enormously labor intensive and complex process was passed along to families, including Uncle William and Aunt Sally Creech at Pine Mountain. The Creeches knew the processes and shared the information with Katherine Pettit. Just how their processes compare to European practice invites further study. Uncle William certainly saw an opportunity to pursue his farming interests, particularly flax, and to combine this with the practice of weaving. Labor in the nearby school was available to him but he also had a sincere desire to improve the production of farm land, to educate, generally, and he, like Aunt Sal, was a consummate teacher. It is clear that he shared these interests in common with Katherine Pettit.

The raising of flax and its processing for the weaving of linen cloth is another long education and another story. It is evident, however, that farming and weaving and education make good partners, whether, wool, flax, or cotton, “Summer Weave”, “Snail’s Trail,” or Virgil, or Longfellow, the threads come together. It is true that the partnership of farming and weaving can be found repeated throughout the world, but the patterns derived from those partnerships are as diverse as the cultures that created them.

A GALLERY OF APPALACHIAN WEAVERS AND SPINNERS

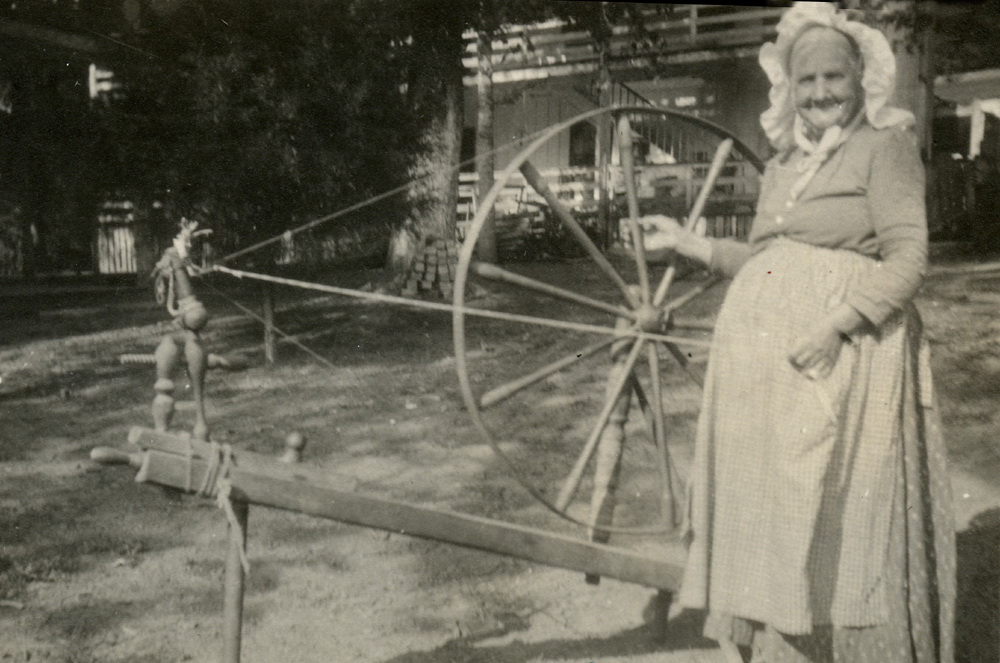

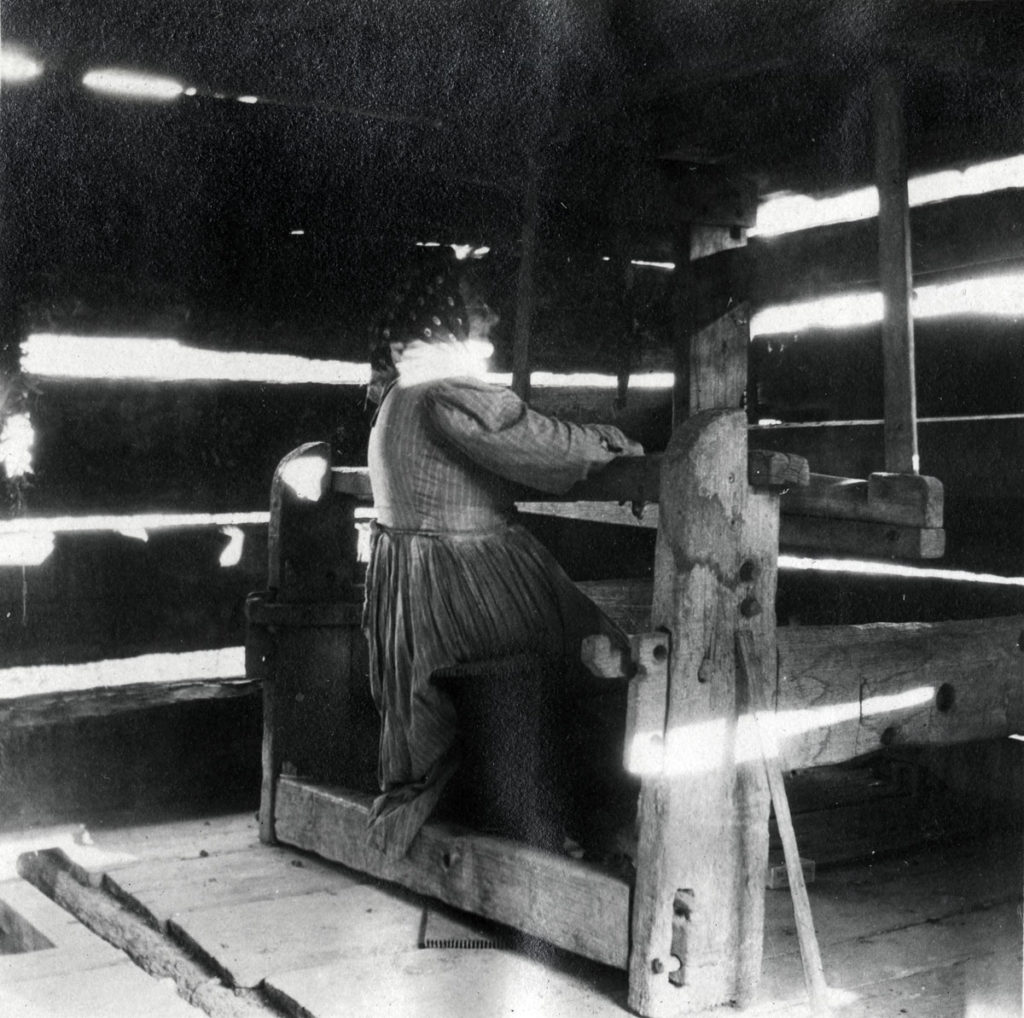

Aunt Sal at her loom in her pioneer house, Aunt Sal’s Cabin [mccullough_II_059b.jpg]

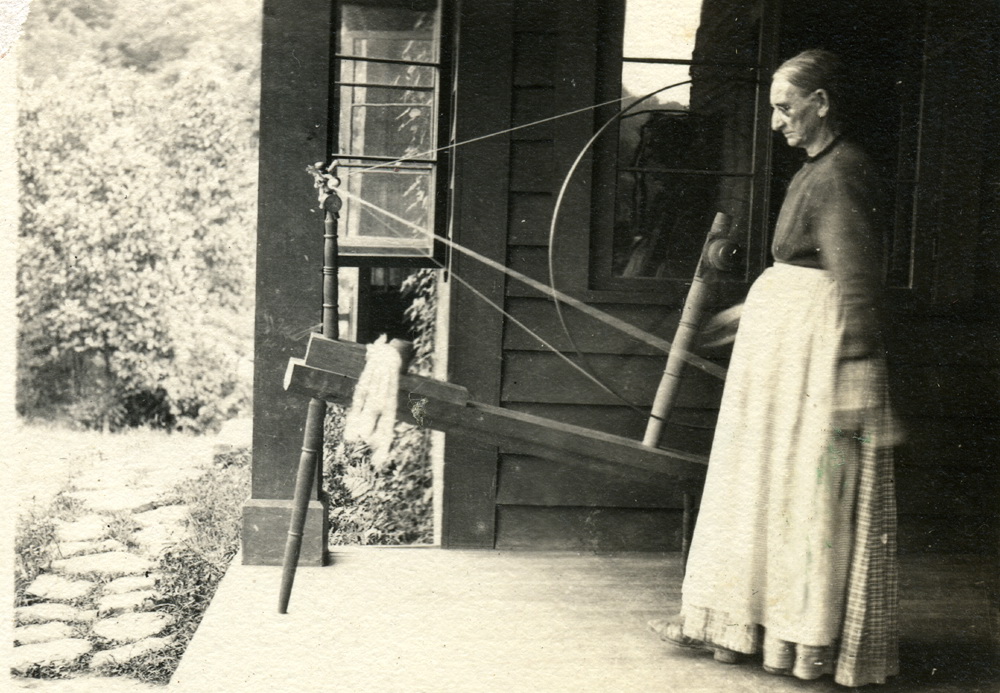

Woman weaving at “Old Loom.” [nace_II_album_020.jpg]

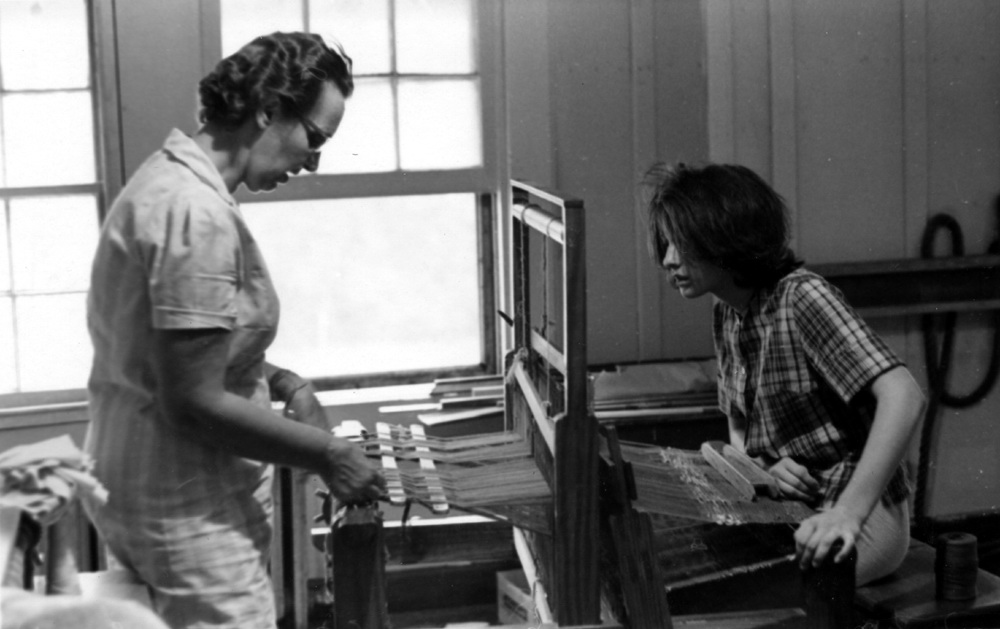

Edna Patterson at loom with student. 1960s-1970s 086_VII_life_work_027.jpg]

Eva repairs and reorders the Weaving Room loom, 2019. [P1150206.jpg]

See Also:

KATHERINE PETTIT Social Settlement in Kentucky Mountains Sassafras Album 1901

CRAFT WORKSHOPS at Pine Mountain Settlement School

For a schedule of events at the School, see:

http://www.pinemountainsettlementschool.com/events.php