Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 12: LAND USE

Lands Unsuitable for Mining Petition

2001

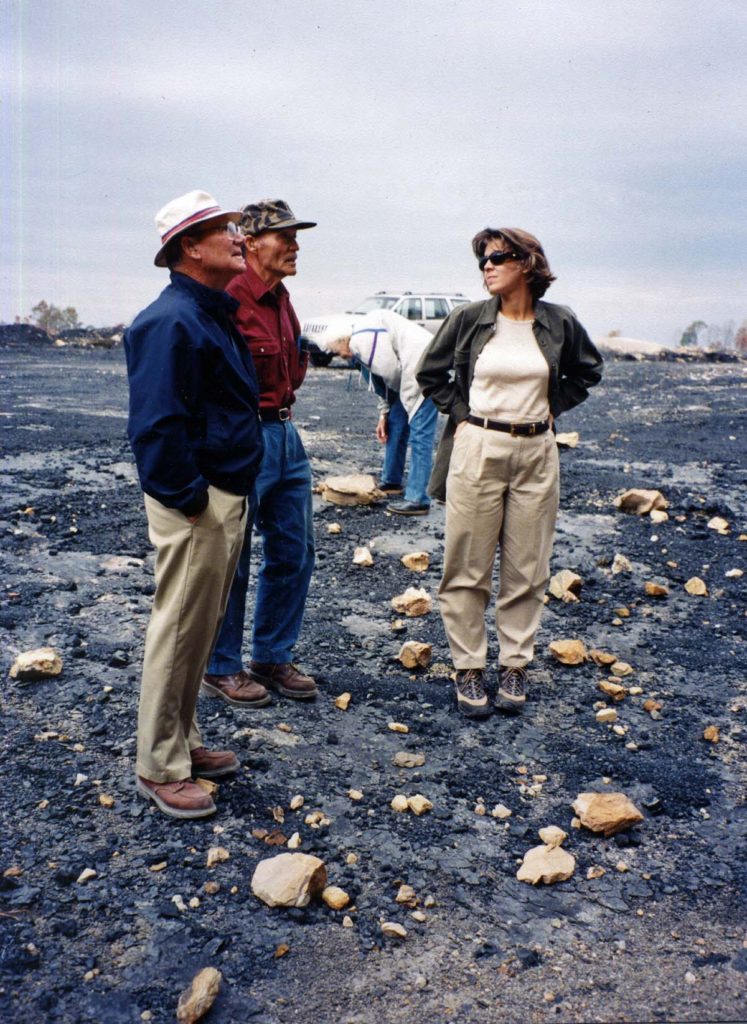

(lft to rt) Springer Hoskins, William Hayes, Robin Lambert on a surface mining site, c. 2001. (Fern Hayes in background.) [lands_unsuit_001.jpg]

TAGS: Land Use, Lands Unsuitable for Mining, petitions, surface mining,;strip mining, environmentalism, coal, land use, Governor Paul Patton, Kentucky Department of Natural Resources, James Bickford, Robin Lambert, William Hayes, Paul Hayes, Mary Rogers, reclamation, Springer Hoskins, coal washing

LAND USE Lands Unsuitable for Mining Petition

In 2001 a resolution that became HR 33 and called “Lands Unsuitable for Mining,” was drafted as a petition from Pine Mountain Settlement School to restrain surface mining on the lands surrounding the School.

TRANSCRIPTION

The House Resolution #33 read as follows (from the unofficial copy of the Resolution).

A RESOLUTION in support of the Pine Mountain Settlement School.

WHEREAS, on November 13, 2000, the Pine Mountain Settlement School filed with the Kentucky Department for Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement, a petition to declare 5,226 acres of land surrounding the historic school as unsuitable for all types of coal mining operations; and

WHEREAS, the Pine Mountain Settlement School, located in Harlan County, is a National Historic Landmark that provides a unique resident outdoor environmental education experience to over 3,000 school children each year, and has been a cultural and educational resource and an employer to the community for over 85 years; and

WHEREAS, a proposed mountaintop mining operation on the Cumberland Plateau to the north of the school property could disrupt the mission, the historical setting, and the viability of the Pine Mountain Settlement School as a National Historic Landmark and outdoor education center; and

WHEREAS, the Board of Trustees of Pine Mountain Settlement School has filed a Lands Unsuitable for Surface Mining petition alleging that surface coal mining operations will affect historic and fragile lands and could result in significant damage to important historic, cultural, scientific, aesthetic values, natural systems, and spring-recharge areas on Pine Mountain that serve as a water supply for the school; and

WHEREAS, the House of Representatives expresses its deep concern regarding the damage coal mining may inflict on the Pine Mountain Settlement School and its rich cultural, historical, and natural heritage;

NOW, THEREFORE,

Be it resolved by the House of Representatives of the General Assembly of the Commonwealth of Kentucky:

Section 1. That Pine Mountain Settlement School has been a truly important Kentucky institution for thousands of students and community residents and others who have participated in its programs over many years.

Section 2. That the House of Representatives recognizes the importance of coal mining to the state and local economy, and the House also acknowledges the growing importance of protecting unique and special places like the Pine Mountain Settlement School.

Section 3. That a designation of the areas with coal reserves within the petition area as unsuitable for mining is appropriate in order to protect the long-term viability of the school, which has served as a cultural, educational, scientific, and historical resource for almost a century.

Section 4. That the Clerk of the House of Representatives shall transmit a copy of this Resolution to Governor Paul Patton and to Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Cabinet Secretary James E. Bickford.

EXPANSION OF SURFACE MINING

Since the early 1960s surface mining in Eastern Kentucky expanded at a rapid pace. The action of surface mining is different from the more common practice of underground mining. The most obvious difference is that surface mining removes the earth to extract the coal. Underground mining removes the coal from the earth. Often referred to as “strip mining,” the surface mining of coal joined other coal removal practices that also “strip,” or use conventional practices in conjunction with other underground coal removal practices.

“Area stripping,” a practice used in Western Kentucky cuts long, deep trenches in a parallel pattern, to reach the coal beneath the flat land of the region leaving behind long parallel piles of “spoil” in the mining area. “Contour stripping,” is a mountain practice that first cuts a shelf or bench along the edge of a mountain above a coal seam and pushes the “overburden” over the slope of the mountain. The resulting “highwall” above the exposed coal seam can scar the face of a mountain or ring it completely, or create several “shelves” or “benches” as multiple coal seams are mined.

“Augering’ is a practice that can be used in combination with “Contour stripping” and is sometimes used to retrieve coal exposed deep in the mountain after the coal is removed from the shelf or bench. The auger operation produced deep (100-200 foot) auger holes that pull coal from the horizontal seam.

To grasp the rapid deployment of surface mining in Eastern Kentucky one need only look at the statistics related to surface mining permits in Kentucky. In 1968 11,100 acres of land was permitted. In 1969 13,700 acres was permitted. In 1970 the acreage increased to 23,600 with some 174 new surface mining permits issued for new mines in that year. [Department of Reclamation statistics, 1970]

LAND DEGRADATION BY SURFACE MINING

It did not take long before landowners, particularly those who had sold their mineral right in an action known as the “Broad Form Deed,” to realize that the practice of surface mining was not an action under their land, but a destruction of their land surface. Instituted at the turn of the century, the Broad Form Deed purchased the mineral rights under landowner’s property — often for as little as .50 cents and acres. The wording of the “Deed” allowed coal companies to do whatever necessary to extract the mineral [coal] they had purchased. Not only were there landslides, erosion, and siltation, considerable acid and mineral pollution of nearby streams also occurred. As reported by the University of Kentucky from a survey conducted by Dr. Wayne Davis, the levels of iron and manganese in the North Fork of the Kentucky River at Hazard saw an increase from 0.02 and 0.00, (prior to surface mining), to 2,1 and 0.8 ppm levels in 1966. Public Health tolerances limit the level of iron and manganese in drinking water to 0.3 and 0.05, respectively.

Another impact of the increased degradation of land is the economic depression of regional communities that sometimes follows mining. The use of enhanced mining techniques reduced human labor and the correlation of out-migration of workers with the most depressed counties in Eastern Kentucky. The consequent decrease in the tax base further challenged these counties. Harlan County has been particularly hard hit and not just once but successively. The record of decreasing support to schools and social services can be correlated with the boom and bust cycle of coal mining in the county. The passage of the coal severance tax in 1972 increased the revenues for schools and social services in Kentucky and Harlan County but with the current downturn in mining, the tax has dropped by nearly 25% from the severance revenues it received in 2012. Harlan Judge-Executive Dan Mosely notes that the current revenue In Harlan County from coal severance tax is around $7000,000. This is amount is from coal and other minerals

The passage of the coal severance tax in 1972 increased the revenues for schools and social services in Kentucky and Harlan County but with the current downturn in mining, the tax has dropped by nearly 25% from the severance revenues it received in 2012. Harlan Judge-Executive Dan Mosely notes that the current revenue In Harlan County from coal severance tax is around $7,000,000. This is the amount from coal and other minerals remaining to be mined, not mined minerals and coal. [http://wfpl.org/mineral-rights-bills-cause-kentucky-counties-take-hit/ Accessed 2016-08-12]

When coal “boomed” another industry also profited. Highway construction crews benefited royally from surface mining as the occupation was often comprised of crews who came to Eastern Kentucky and used their skills to form the base of many of the fledgling surface mining coal companies. The manipulation of the vague 1966 surface mining regulations ensured that the benefits of surface mining stayed with the coal operators and very rarely with the landowners. Two State regulators, Elmore Grim, State Reclamation Director and Bill Hayes, District Supervisor for the Hazard District Office of State Reclamation, Department of Natural Resources, charged that their jobs were designed “… not to prevent damage from surface mining, but to “minimize” it.

Regulators within the State Reclamation Office were often at odds with the Department of Transportation which rarely was sympathetic with efforts to curb surface mining. Two State regulators, Elmore Grim, State Reclamation Director and Bill Hayes, District Supervisor for the Hazard District Office of State Reclamation, Department of Natural Resources, charged that their jobs were designed “… not to prevent damage from surface mining, but to “minimize” it., suggesting that the full weight of their state government rarely covered their backs. But the discovery of problems also plagued the regulators. Many issues and solutions were not in any training manual when regulation began to address surface mining in the state. Grim is quoted in those early years as saying, “Hellfire, we’ve got some problems. This is [a] trial and error process. We’re writing the book as we go along.” [“Strip Mining for Coal in Kentucky: Questions and Answers.” Save Our Kentucky flyer, c. 1971] Bill Hayes, a former Pine Mountain student and later Farm Manager, early-on called the regulations “inadequate” and eventually resigned his job in 1976 in protest of the lax support from the State for enforcement. [Coal Facts. August 19, 1971.] Needless to say, the issues between the State and its regulators were not issues that were mediated in a climate of cooperation. The resistance of legislators, governors, and various state offices was persistent and continued well into the 1980’s.

It was in this contentious climate that Pine Mountain engaged the coal mining industry and the state in its “Lands Unsuitable for Mining” action. They drafted a declaration document that clearly spelled out their position regarding mining on lands “unsuitable” for mining adjacent to the Pine Mountain Settlement School. What is remarkable regarding this action is its success. The weight of public opinion was clearly shifting by the 1980s. The action of the settlement school and the subsequent passage of the “Lands Unsuitable for Mining” petition by the Kentucky Legislature was a remarkable negotiation of the local as well as the state political landscape. While Pine Mountain was not the first public effort to curb surface mining in environmentally sensitive areas, it was remarkable in its passage deep within “coal country.” A previous State petition which was the first Lands Unsuitable for Mining Petition approved, designated 2,900 acres in the Cannon Creek Reservoir in Bell County in 1987. The Pine Mountain Settlement School petition passage in 2001, thirteen years later, was enacted to restrain mining surrounding the School.

LANDS UNSUITABLE FOR MINING Planning Document

The document for the planning process to enable the passage of the petition follows:

350.610 Designation of lands as unsuitable for surface coal mining

(1) The secretary of the Energy and Environment Cabinet is hereby authorized to establish a planning process enabling objective decisions based upon competent and scientifically sound data as to which, if any, lands of the Commonwealth are unsuitable for all or certain types of surface coal mining operations pursuant to the standards set forth in this chapter; provided, that any such designation shall not prevent coal or other mineral exploration of any area so designated. (2) Upon petition and hearing pursuant to subsection (6) of this section, the secretary shall designate an area as unsuitable for all or certain types of surface coal mining operations, if the secretary determines that reclamation pursuant to this chapter is not technologically and economically feasible. (3) Upon petition and hearing pursuant to subsection (6) of this section, a surface area may be designated unsuitable for certain types of surface coal mining operations if such operations will: (a) Be incompatible with existing state and local land use plans; or (b) Affect fragile or historic lands in which such operations could result in significant damage to important historic, cultural, scientific, and aesthetic values, and natural systems; or (c) Affect renewable resource lands in which such operations could result in a substantial loss or reduction of long-range productivity of water supply or food or fiber products, and such lands to include aquifers and aquifer recharge areas; or (d) Affect natural hazard lands in which such operations could substantially endanger life and property, such lands to include areas subject to frequent flooding and areas of unstable geology. (4) Determinations of the unsuitability of land for surface coal mining shall be integrated as closely as possible with present and future land use planning and regulation processes at any appropriate level of government, including but not limited to any valid exercise of authority of a municipality or county, acting independently or jointly, pursuant to KRS Chapter 100. (5) The requirements of this section shall not apply to lands on which coal mining operations were being conducted on August 3, 1977, or under a permit issued pursuant to this chapter or where substantial legal and financial commitments in such operation were in existence prior to January 4, 1977. (6) Other provisions of this chapter relating to hearings to the contrary notwithstanding, any person having an interest which is or may be adversely affected shall have the right to petition the cabinet to the extent such a petition would be consistent with subsections (2) and (3) of this section, to have a specific and well-defined area designated as unsuitable for surface coal mining operations, or to have such a designation terminated. Such a petition shall contain allegations of facts which shall be specific as to the petitioner’s designated area, including a justification that the criteria alleged occur throughout and form a significant feature, and shall be based upon objective evidence which would tend to establish the allegations. The cabinet shall make a determination or finding whether the petition is complete, incomplete, or frivolous. Within ten (10) months after the receipt of the petition, the cabinet shall hold a public hearing in the locality of the affected area, after appropriate notice and publication of the date, time, and location of such hearing, pursuant to regulations promulgated by the cabinet to implement this section, provided that when a permit application is pending before the cabinet and such application involves an area in a designation petition, the cabinet shall hold the hearing on the petition within ninety (90) days of its receipt. After a person having an interest which is or may be adversely affected has filed a petition and before the hearing, any person may intervene by filing allegations of facts with supporting evidence which would tend to establish the allegations. Within sixty (60) days after such a hearing, the cabinet shall issue and furnish to the petitioner and any other party to the hearing, a written decision regarding the petition, and the reasons therefor. In the event that all petitioners stipulate agreement prior to the requested hearing and withdraw their request, such hearing need not be held. Within thirty (30) days after receipt of an order, determination, finding, or decision by the cabinet or the secretary hereunder, any applicant, or any person with an interest which is or may be adversely affected and who is aggrieved by the order, determination, finding, or decision of the cabinet or secretary, may obtain judicial review thereof by appealing to the Circuit Court of Franklin County pursuant to the provisions of KRS 224.10- 470. (7) Prior to designating any land areas as unsuitable for surface coal mining operations, the cabinet shall prepare a detailed statement on: (a) The potential coal resources of the area; (b) The demand for coal resources; (c) The impact of such designation on the environment, the economy, and the supply of coal; and (d) The characteristics of the petition area including a justification that the criteria alleged occur throughout the petition area and form a significant feature. (8) Subject to subsection (5) of this section, the cabinet shall not issue a permit to conduct surface coal mining and reclamation operations in contravention of any designation or any decision on any petition pursuant to subsection (6) of this section regarding any surface area designated unsuitable for mining; nor shall the cabinet issue a permit to conduct surface coal mining and reclamation operations in an area under study for such designation in an administrative proceeding already commenced under subsection (6) of this section. Effective: July 15, 2010 History: Amended 2010 Ky. Acts ch. 24, sec. 1895, effective July 15, 2010. — Amended 1984 Ky. Acts ch. 180, sec. 1, effective July 13, 1984. — Amended 1982 Ky. Acts ch. 283, sec. 8, effective April 2, 1982. — Created 1980 Ky. Acts ch. 62, sec. 36, effective March 21, 1980. Legislative Research Commission Note (7/11/91). A technical correction has been made in this section by the Reviser of Statutes pursuant to KRS 7.136 and 7.140.

See Also:

LAND USE Guide

LAND USE Dollar Branch

LAND USE Dollar Branch Correspondence

Robin LAMBERT Director Biography (PASSWORD PROTECTED)

SPRINGER HOSKINS Trustee Biography

WILLIAM HAYES Part III Biography