Pine Mountain Settlement School

DANCING N THE CABBAGE PATCH

Christmas at Pine Mountain 1915 and 1917

Christmas 1915

TAGS: Evelyn Wells ; Ethel de Long ; opened packages ; filled stockings ; trimmed the house ; delivered trees to neighbors, Aunt Sis Shell, Aunt Polly Day, Aunt Sal ; Santa played by Mr. Zande ; hung stockings ; children received gifts ; trimmed tree in House in the Woods ; snowed ; pageant of carols ; manger scene ; Bettie Cornett as Mary ; visit by Santa ; arrival of drunken visitors ; dinner before fireplace at Far House ; arrival of Christmas mail ; mule ride across mountain ;

Christmas 1917

TAGS: no longer drinking and shooting at Christmas ; preference for simple gifts from nature as delivered by neighbors ; letter from Santa mandating good behavior ; birthday cake from Santa ; children delivered baby Christmas trees to neighbors ; [comments on narrow views in narratives and missions of settlement workers, balanced by their good works ; fine line between “work” and “production”] ; Nativity Scene ; visit by Santa ; need for donations ;

Transcriptions

Christmas 1915

*From the notes of Evelyn Wells, derived from letters of staff at Pine Mountain Settlement School. The author is unknown but is possibly Ethel de Long who served as Housemother at Far House in 1915. The use of “Aunt” or “Uncle” is used frequently as an acknowledgement of respect and friendship and not as a familial kinship.

This week we have been sitting up half the night opening the packages that came in — a mixed bag! — and filling tarletan stockings with candy by the hundred (575 in all), and then the family stockings. School stopped on Wednesday, luckily, considering all that had to be done. We trimmed the whole house with laurel and hemlock — ropes, baskets and wreaths everywhere until it was like bringing in all outdoors, so fragrant and woodsy. Thursday afternoon we took the little Christmas trees to Aunt Sis Shell and Aunt Polly Day. We cut the trees along the way and trimmed them by the roadside, and then bore them to the houses, singing “Here we come a-wassailing,” as we arrived. What a picture the children made as we went through the yard at Aunt Polly’s — a yard for the pigs mostly — and into her one-room cabin where she sat coughing and moaning and trying to knit. She was quite cheered however by our visit, and was even moved to show interest in the things we brought her. People around here usually say nothing at all in acknowledgment of a present, though they are really very grateful. Aunt Polly’s daughter came in from milking as we were leaving and showed us her twelve-day-old baby, all done up in red flannel and quilts.

Friday the children took a tree up to Aunt Sal‘s, but didn’t go in, of course (quarantine) [smallpox]. Aunt Sal is almost ready to be released from quarantine, and we left the tree at the gate and she came out and got it. The day was so warm that we had our supper on the terrace by lantern light, and just as we were finishing, Santa Claus arrived with gifts for all the family, and the children were quite overcome. Santa was Mr. Zande, and very adequate in the role, though wordless. He had wanted to give everyone presents and I had stayed up till 12:30 the night before, tying them up, so I was quite surprised to get another gift from him — a handkerchief and a box of face powder. Likewise, gifts for Mrs. Light and Miss Lincoln.

Then we went in and had the big Christmas tree, and hung our stockings up — with the exception of two bad boys who had lost that privilege — such a sad time for them! Then the children — lucky things — went to bed and after fried eggs and bacon, cake and oranges, we went to work. Candy, hair-ribbons, knives, tops, books, dolls, aprons, shirts, awfully nice things, eight presents for every child, and stockings up for the two bad ones after they had gone to bed. All the house presents were put in Miss de Long’s stocking, nice toys and books and a beautiful doll. By one o’clock we were in bed and it had started to rain, and the next thing I knew the waifs were outside my window, — singing.

At six we lit the tree and the children came in to their stockings, and had a rapturous hour of it. But such rain — Just teeming! After breakfast, to the accompaniment of French harps — every child got one — I went up to the House in the Woods to trim the big tree, with Mr. Zande’s help, and some of the hands. One very nice box we’d had was a big collection of Christmas tree ornaments from Marshall Field’s, and we really achieved a lovely tree.

About 9:30 the rain turned to snow, which continued all day, piling up everywhere and absolutely transforming things. We didn’t have a big assemblage on account of the weather, only about 150, mostly men. They began to arrive very early, of course, and I set them all to work decorating.

![[Isaac's Creek?] nace_1_078a.jpg](https://pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/nace_1_078a-1024x672.jpg)

[Isaac’s Creek?] nace_1_078a.jpg

The exercises began at eleven with our pageant of carols, which was very lovely in its simplicity. Our manger scene, with Bettie Cornett in a purple veil bending over a manger constructed by Chester that morning, and the shepherds with crooks and gifts, and the Three Kings bearing staffs tied with holly, all against a background of laurel and snow, was beautiful. The little children were to play Old King Cole, but the King was overcome with embarrassment and began to cry, and it was fortunate that Santa appeared just then to distribute candy and snappers and balloons.

It’s such a shame that some unpleasant things interrupt all this gaiety — such as Alec Day, such a nice man, coming with several others as drunk as lords. But of course Christmas is their best time for drinking and shooting. One man at the school’s first Tree got up and made the following temperance speech: “Hit’s been put upon me to tell you fellers as how the school-women don’t want no drinking at their Tree. That’s mighty hard on us, but we’ll have our drams the day before and the day atter Christimas, and then we’ll have two Christmasses!”

We ate our dinner around the fire at Far House, and afterwards the children played with their new treasures and the grown-ups did nothing — a great treat. I was going to have a tea-party for the little girls so they could use their new dishes, but they’d really had enough done for them so the party is put off till some other long winter day.

It was a wonderful afternoon, with the snow piling up outside so quietly, and a fire within. We went to bed early, the children in a blissful state of mind. And after they were all in bed, the Christmas mail came in, a wonderful ending for us.

The next morning we slept late, and the sun was shining on the ridges across the valley, all snowy and bright. I crossed the mountain on a mule, a heavenly ride up through the silent woods, with the trees showering snow on me as I went along.

(This letter was written on the train from Harlan to Pineville, on my way out to “vacation.”)

Christmas 1917

*The following description of Christmas is taken from a much quoted account of the 1917 Christmas at the School.

Dear Friend:

This letter is a Christmas reminiscence from Pine Mountain.

“Well, Christmas, hit used to be the rambangin’est, shootin’est, killin’est, chair-flingin’est day in the hull year till the school come, and now look what a pretty time we’ve had today. I didn’t know you could git so many folks together and have sich a peaceable time. I never did come to one of your Christmas trees before, but I seed you never had a killin’ at em yit. So I come this year.”

Not a chair was flung at Pine Mountain on Christmas, nor a dram drunk, and no one was killed! These are meaningful negatives to us at the ‘Back of Beyond,’ telling of something accomplished since that Christmas two year ago when we collected the pistols before the party began. But you ‘furriners,’ who have dwelt under the wig of peace, ‘since allus ago,’ can scarcely imagine how pretty a time the negatives made possible.

Our neighbors know that we like gifts of hemlock and holly and mistletoe better than any ‘fotched-on’ presents. So, for two weeks before Christmas, we were continually interrupted by visitors bringing us greens; — grey worn figures, honest, plain, kindly faces — what a glory they gained from the marvelous boughs of holly or the great bunches of mistletoe that somebody had ‘clomb a tree fer.’ The golden apples of the Hesperides could be give with no sweeter grace. Sometimes a neighbor brought us a gift of eggs, a rarity at Christmas when the hens ‘ain’t layin’ good,’ Sometimes honey just ‘robbed’ out of a bee-gum, and once it was a great bunch of gorgeous ‘feathers of the pea-fowl.’

Some ten days before Christmas, just at dusk, Santa Clause left a letter at our gate, full of kindly information about himself and his ways for the thirty or forty children who had never seen Christmas before. He not only laid stress on his well-known love of good behavior but went into particulars, writing: ‘I won’t bring any candy to little boys or girls who leave their nightgowns on the floor in the morning or don’t open their beds, or keep their noses clean.’ Our chattering little boys and girls discussed these commands from every angle and with whole-hearted faith. Much-desired ends were accomplished by Christmas magic.

One night reindeer bells were heard far off. Undoubtedly Santa Clause must be riding along the hill-tops hiding presents against Christmas Eve, when he could not possibly bring enough for all from the North Pole. The children, just dropping off to sleep in the dark of the sleeping porches, quivered with joy; but small William, six years old, remembered the least boy’s morning shortcomings. ‘Pleath, Santa Clause,’ he called out in the dark, ‘ecthcuse Cam just thith once for leavin’ hith nightgown on the floor. He won’t never do it again.’

A few nights later, when the bells were heard again as the children were undressing, little Green already in his pajamas, dashed across the room for his handkerchief. ‘Look out for your noses, fellers,’ he called, ‘thar’s Santa Claus.’ And then, with irreproachable nose tilted high he leaned against the window, hoping that Santa Claus would favorably note him.

One night, when we were all at supper, Santa Clause left a birthday cake for himself on the living room table. No other explanation could account for the mysterious frosted cake loaded with candles, and exclaiming on its top in red letters: ‘Merry Christmas!’ Every night the baby Christmas tree was lighted, when the children danced around it, singing Christmas songs and blowing kisses to it.

The day before Christmas each one of our four households carried its baby tree to some dear old neighbor’s. If you could know how those trees are cherished! Sometimes they are kept through a whole year, treasured as a joy even when the needles have dropped off. To one old lady, living three miles off at the backside of a mountain in a dark little windowless house, the children carried a window — a common barn sash left from our building operations. ‘Why,’ she said, ‘why, I wouldn’t take ten dollars for my window. I’ve had to set in the dark by the fire cold or windy days when the door had to be shut, and I couldn’t see nothin’. There haint much to see here, way off the road, at the head of the holler as we be but hit’s mighty lonesome in the dark on a winter’s day.’ Then, carrying her little window gently in her arms, she laid it on the bed in the one safe place in the room. ‘Lord. I wouldn’t take a nigger baby for my winder,’ she cried.

[Racist remarks such as this one, are all too commonly found in narratives of both the School and community in the early years of the Institution, as they were in much of the literature of the day. Reaching out to those in isolation — “… those that sit in darkness,” was perceived to be a critical mission of many workers in the settlement movement.

For those settlement workers in the rural Appalachians, a common belief was pervasive — that the people of Appalachia were of “pure Anglo-Saxon” stock and that they represented long-lost ancestors that could be “raised -up” through education and the re-introduction of traditional English and Scots-Irish rituals and traditions. Christmas, May Day, and other pageants and rituals were often used to re-introduce and to underscore the connection of the mountain people to their Anglo-Saxon heritage. This folk-heritage belief and crusade was attractive to many workers of the first part of the twentieth-century.

Today, in our multi-cultural world, such views are those of people “who sit in darkness”, no matter their education, wealth, or status. These narrow views do not, however, negate the well-meaning intentions and results of these early social service crusaders. The results of their good work in the areas of general education and health and health literacy were profound and lasting. The need for intervention was critical but the balancing act of social service and social engineer, was sometimes uneven.

The fine line between “work” as something irreplaceable and unique, and “production” as something that conforms to a common product, a nature or a production, is a very delicate process and one that continues at the School, even today. Letters, such as this one to ‘Friends’ of the School, had a broad appeal and kept programs alive at the School and helped to “produce” new ones as times dictated. Early letters to family and friends are far more candid than the letters to board members and supporters and often reflect personally held beliefs that stand in deep contrast to the mantras of settlement work and to the beliefs of the populations they served.

The social space in which these Christmas events took place is not a thing among many things or a product of some thing. It is its own set of knowledge that subsumes relationships and products and beliefs. It is a process that still continues as the School struggles to work with populations that are impoverished and illiterate and deep within the valleys and hollows of Appalachia but also works to reach all those “who sit in darkness” with regard to their environment, no matter if the source of that obscurity is in deeply rooted urban life-styles or in denial of climate change.]

The narrative continues:

Was this the sweetest incident of Christmas, the carrying of light to those that sit in darkness? Or was it the caroling of the boys at four o’clock in the morning, singing through the dark from house to house, “Hark, the herald angels sing,’ and ‘God rest you, merry gentlemen.’ To the small ones of course the dearest moment came when their stockings were handed to them, and they drew out barley candy and oranges, a French harp or a doll, — some trick the like of which had not come to their ken before. Table manners at breakfast were suspended while whistle and harps and laughter and ‘Christmas gift,’ perceptibly reduced our daily consumption of oatmeal.

Of course, there was a beautiful community tree, and how peaceable a time we had at it you already know from the first sentence of this letter. Some five hundred people came, among them an old lady sixty-nine years old, who had started before day to come clear across Pine Mountain. ‘I’ve never seed a tree,’ she said, ‘and I allowed thar mought be a pretty one the tree for an old woman sixty-nine years old, what had ever seed one.’

Silent and spell-bound, we all watched the progress of the beautiful Nativity Scene, which had the simplicity and sweetness of an early mystery play. Then Santa Clause came tramping through the woods. We hailed him with joy, we laughed at his jokes and we had a “big time” flinging confetti at him and blowing balloons in his honor. You, who treasure your Christmas ornaments from year to year with wise economy, do not blame us that we gave most of ours away to the mothers who looked so wistfully at the radiant wonders on the tree, and who carried the tinsel and the balls home to brighten lives and homes already too grey.

I cannot write you of all the bits of joy, that pieced together made Christmas so lovely a mosaic. It seemed to us that the wealth of beauty that centuries have given the Christmas festival was all flung into our laps. We want you to share with us the most beautiful Christmas we ever knew, and then we want you to share with us the shrinking of spirit we feel as we think of the months from April to August, when we go through the profoundest anxiety about money.

The School is too large now with its seventy children, to be kept in cold storage through the pleasant Spring and Summer, when givers forget that there are wolves howling at poor folks’ doors. Now, while it is cold and poverty seems bleakest, will you not help us to build up our annual income to carry us through the year? We want five hundred givers of one dollar a year, five hundred of two dollars a year, and five hundred who will give five dollars a year. If you are already a subscriber, won’t you try to find somebody who will fill out the enclosed card? We will tell them of our children, and not send merely a cold receipt. They shall hear of our six-year-old who wanted to ‘do somethin’ for his country’ with a penny he earned carrying kindling for twenty minutes in his play-time; or the little girl who wrote Santa Clause for two tooth-brushes — one for herself and one for her little sister at home.

We workers who for weeks last Summer faced the question of breaking up school and sending the children home and saw our bank account drop to one cent, feel that another such experience will put us in the class the preachers pray for, ‘those whose heads are abloomin’ fer the grave.’ Please help us find another Rock of Gibraltar, — an annual giver.

Sincerely yours,

Ethel de Long

Return to CHRISTMAS – GUIDE

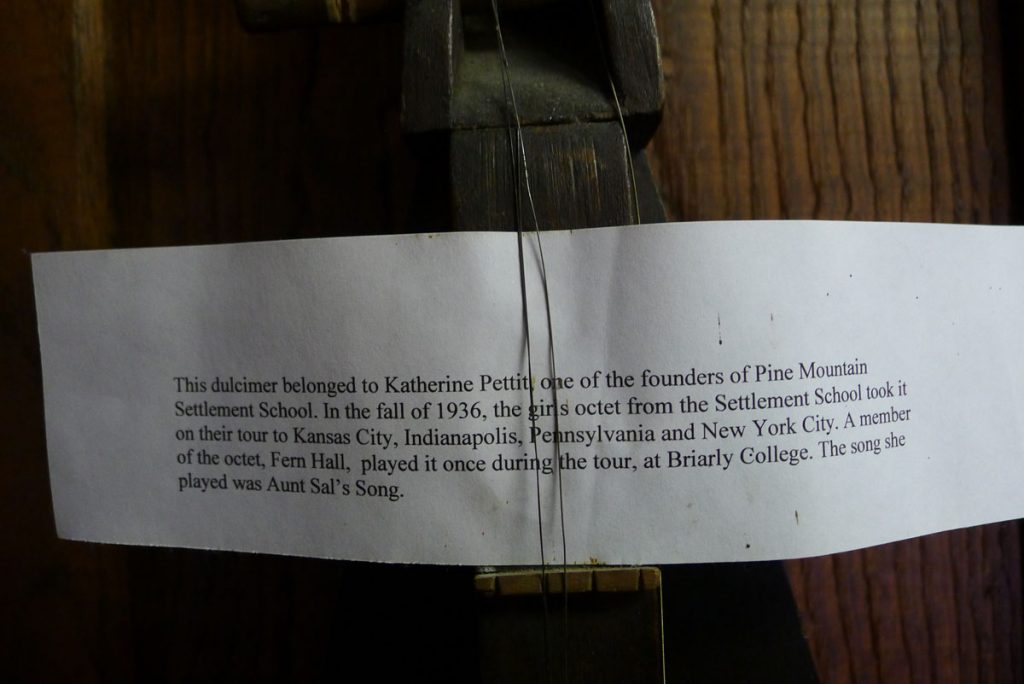

![Angela Melville Album II - Part III. "E.K.W." [with dulcimer]. [melv_II_album_313.jpg]](https://pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/melv_II_album_313-194x300.jpg)

The isolation of the region was slowly but dramatically altered by roads, particularly

The isolation of the region was slowly but dramatically altered by roads, particularly

![[Isaac's Creek?] nace_1_078a.jpg](https://pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/nace_1_078a-1024x672.jpg)