Pine Mountain Settlement School

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH II

INTRODUCTION – Growing From the Soil

Land in the Southern Appalachians is precious soil. The people grow from the soil as surely as plants take root and spring upward towards sun. The people grow strong to work the soil and they bend as the soil pulls their tired bodies back to lay in peace within it. Yet, the cycle is more a dance than a dirge. The dance is the dance so many children and adults have today forgotten. It is the jitterbug of stream-beds and the waltz of wind-blown mountain tops. It is the courtly movement through rows of cabbages and corn. It’s the balanced step-dance across a foot-log. It is a dance that educates for wholeness; the kind of wholeness often found in the rhythm of rural country sides.

Dancing in the cabbage patch was part of the early education at Pine Mountain Settlement School. It was not an education just for children. It was the exercise of everyone who marveled at the cycles of life and the bountiful bloom of new crops as they re-shaped flat field and high hill. It was and is all that is intuited in the fragile relationship with the land. A dance in the cabbage patch is an exercise in the nourishment of both body and soul. It is a solo dance made joyful by the sharing.

We can dance alone, or we can grow the patch together. At one time Pine Mountain raised over 10,000 heads of cabbage in their central garden patch. Today, together, the cabbage patches are unlimited for us all if we can re-connect with the land.

The blog Dancing in the Cabbage Patch is structured into a series of essays about Pine Mountain and its Community. It explores the land of Appalachia, its farming, its foodways, and its celebrations. It is a history of a unique rural Appalachian settlement school that spans an existence of more than 100 years.

_________________________________________________________

The foundation of Pine Mountain Settlement School can be found in the early efforts of key visionaries in both the School and the community. Some of these unique individuals are described in their BIOGRAPHIES as compiled by the two authors of this blog. Other biographical notes may be discovered in the many stories told about each other. The biographies and stories are filled with characters whose lives may not at first appear visionary, but, on closer examination, these are folk who have led many seekers to both truth and fiction, and to a land little understood and often misrepresented.

Some seekers understood where they had been led, but others, clearly, could not shake their myths and prejudices. The Pine Mountain Valley, its land and its people is filled with a clear truth, a fantastical mythology, and a delightful romp through one of the most misunderstood regions of America. In summary, to explore Appalachia is to dive into a deep exploration of the truth tellers, the seekers and those oblivious to dreams, visions, and truth. It is a journey about the evolution of America and its vision of itself.

Read deeply, the stories from Pine Mountain carry echoes of self-will, absence of doubt, and a certainty that comes shining or struggling through these fragments of lives. As School and Community worked together to establish and to give continuity to one of the first rural settlement schools in the Central and Southern Appalachians they left a map for those seeking the meaning of democracy. Not soon to be forgotten are the narratives of the staff and community who helped to shape the vision we now hold of the early rural settlement movement and the foundations of our democracy. In the PINE MOUNTAIN SETTLEMENT SCHOOL COLLECTIONS ARCHIVE there are many paths to follow.

THE FOUNDERS

When William Creech gave his land in 1913 so that Pine Mountain Settlement School could begin its journey, he also gave to the School one of the most famous quotes associated with the institution. Katherine Pettit, a co-founder of the School, used Creech’s visionary words for “his people” to promote the institution. The wisdom of William Creech and the surrounding community and of those who came to “save” the community but found themselves for the first time, continues to resonate with many cultures and lives throughout the world. Most all of Pettit’s successors at the School have found this quote to be foundational.

An Old Man’s Hope for the Children of the Kentucky Mountains

I don’t look after wealth for them. I look after the prosperity of our nation. I want all younguns taught to serve the livin’ God. Of course, they wont all do that, but they can have good and evil laid before them and they can choose which they will. I have heart and craving that our people may grow better. I have deeded my land to the Pine Mountain Settlement School to be used for school purposes as long as the Constitution of the United States stands. Hopin’ it may make a bright and intelligent people after I’m dead and gone.

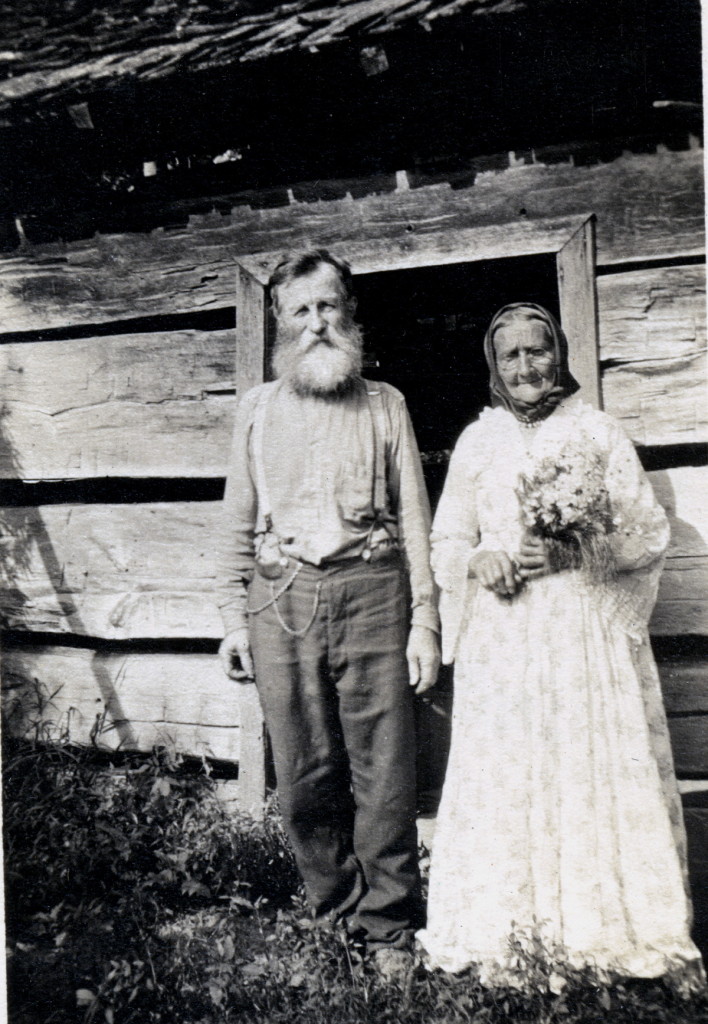

Uncle William and Aunt Sal stand in front of their old home while re-enacting their wedding picture. hook_007_mod.jpg

Uncle William and Aunt Sal donated 135* acres of land for the Pine Mountain Settlement School. [*This acreage varies in the historical record and often includes the donation of other land from community and lumber and mining companies and other families such as the Metcalfs and Wilders and others.]

In this photograph Uncle William Creech and his wife Sally Creech re-enact their wedding in front of their original cabin home in 1917. Now often referred to as “Aunt Sal’s Cabin,” it was relocated to the grounds of the Settlement School in 1926 and is now a central landmark of the School which is on the National Historical Register.

One of the founders of the School, Katherine Pettit (1868 -1938) was a Kentucky native. She began her work at nearby Hindman Settlement School which she also founded, and served as co-director at Pine Mountain Settlement School until her retirement in 1930. For the next five years she traveled throughout the world and continued to doggedly trudge throughout Harlan County urging farmers to adopt modern farming techniques. In 1932, she visited South America. In that same year, she received the Sullivan Medallion from the Univ. of Kentucky as the outstanding citizen of the state of Kentucky. She died Sept. 3, 1938 at the age of sixty-eight.

The co-founder, along with Pettit and William Creech, was Ethel de Long Zande (1868 -1928), a New Jersey native and Smith College graduate. She was recruited by Pettit to be the educational co-director of the School and to give academic guidance, fundraising and educational programming. Pettit knew de Long’s work as the two had served in similar positions at Hindman Settlement School where de Long worked with Pettit for two years. Ethel de Long was as powerful in her beliefs and will as was Pettit and William Creech but that did not prevent them from hiring a multitude of staff that carried the same strengths. Pettit and de Long and their staff provided basic education for children and training for mothers in health, cooking, and home care. In 1918 Ethel de Long married Luigi Zande, an Italian stonemason. She died much too early of cancer in 1928. Her short time at Pine Mountain solidified the joined vision the two other founders, Katherine Pettit and Uncle William Creech, and the three left a lasting legacy and an unmovable foundation for the School.

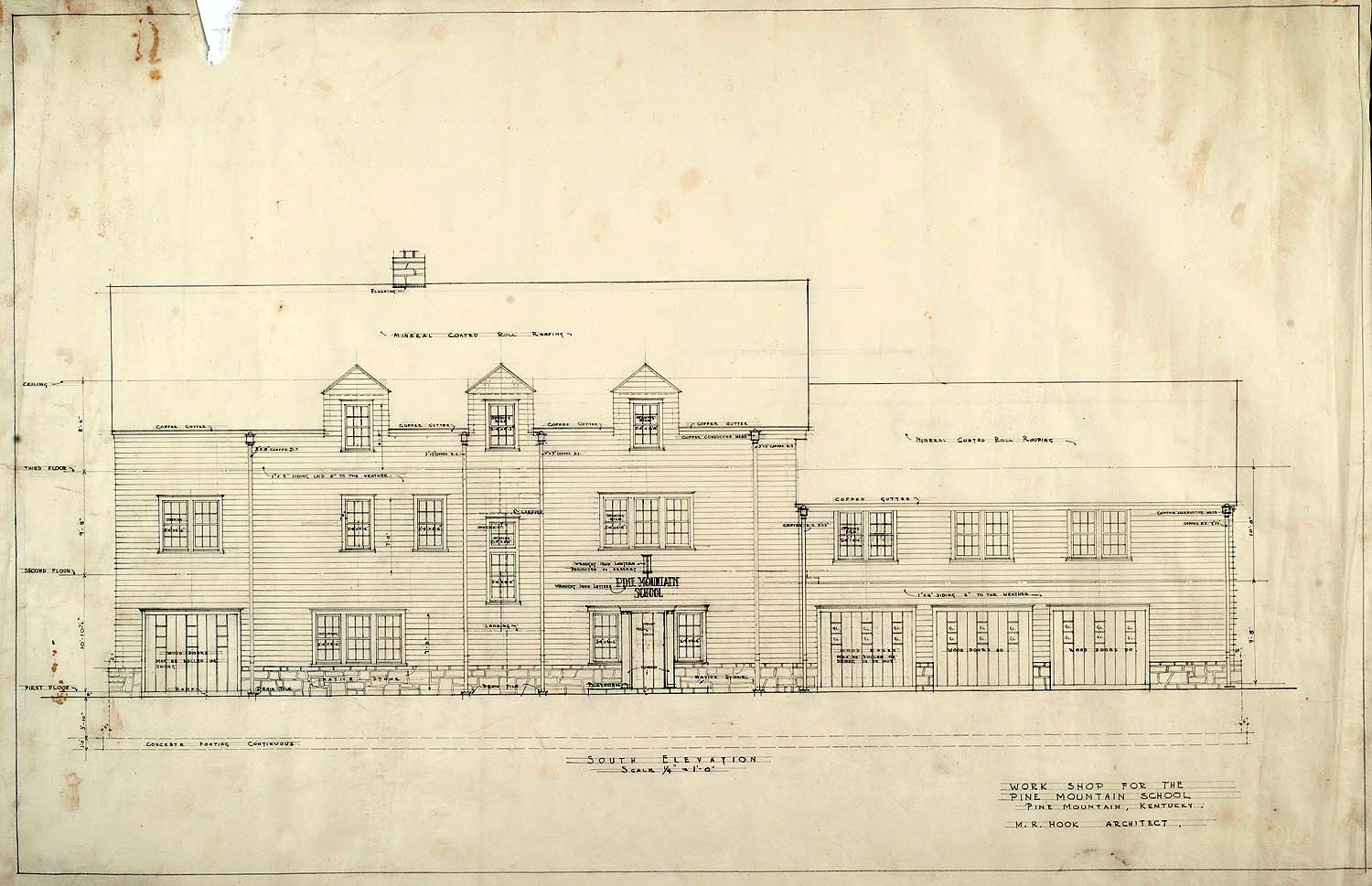

Another force that needs to be reckoned with is that of Mary Rockwell Hook. Mary Rockwell Hook,was recruited to Pine Mountain to serve as the lead architect for the buildings and the grounds of the school. Her work represents one of the first instances of women’s work in the architectural profession. A native of Kansas City, Kansas, and daughter of a banker, she was one of the first group of women to study in the renowned school of architecture in France, the Ecole de Beaux Arts in Paris. Her work represents a major milestone for women architects in America as she was by all accounts, she was among the first women to earn an architectural degree in the United States. It was Mary Rockwell Hook’s remarkable work that earned Pine Mountain Settlement School recognition as a National Historic Landmark in 1983.

Her architecture, like the people grew up out of the land and its organic presence always runs as a sub-text throughout all that is Pine Mountain Settlement School. Mary Rockwell knew the land and the people and she continued to work with the School until her death at the age of 101.

Work Shop For The Pine Mountain School Boys Industrial MSR5852_1 M.R. Hook South Elevation 1/4″=1′-0″ (early proposed plan)

Throughout the literature of Pine Mountain Settlement School one will see individuals acknowledged as “Uncle” and “Aunt” such-and-such. When used with the first names of community members, the familial designation was generally not a designation of a familial blood relationship, but one of endearment. It was used particularly within the staff and families at the School, but it was always a long-held title of respect and endearment in the Pine Mountain community. Following his donation of land for the school in 1913, Uncle William only lived six more years, until 1918. Aunt Sal lived on until 1925. Their passing was as though a near Uncle and Aunt had passed, and they had.

It was the generous donation of land by William and Sally Creech, the Metcalfs and others, and their advocacy and their vision that made the school on the headwaters of the Kentucky River, a reality. But it was community that was the bond that sustained it. When Uncle William and Aunt Sal gave the land they did so with the intent to create a school and they sought out supporters in the community and with the community convinced the two remarkable women to come to the remote valley in Harlan County to became the new Settlement’s directors. Pettit and de Long needed little persuasion and the community was ready for them.

BUILDING THE SCHOOL

In Pettit and de Long , William Creech found a congruence of goals and vision. Pettit and de Long took the educational challenge of Uncle William to heart and Uncle William held the two women close to his own heart and dream. Katherine Pettit, a member of the Lexington chapter of the Kentucky Federation of Women’s Clubs, had, with May Stone, and the support of the Club founded Hindman Settlement School in 1900, and knew what she wanted in a school. Thirteen years later, more importantly, she knew where she wanted a school. Ethel de Long , who had worked for many years as an educator with Pettit at Hindman, was a pragmatic and articulate program creator but, like Pettit, she wanted to chart her own course and exercise some of her new ideas on education in the central Appalachians. Both Pettit and de Long were visionaries, as was Mary Rockwell Hook, but they were all also well connected to other forceful women and men. Their long chain of contacts gave them the foundation and support needed to launch the new settlement school.

The Creeches, Pettit, de Long, and Hook as well as others in the Pine Mountain community were a productive and dynamic combination. The quick formation of an Advisory Board provided the outside oversight, funding, and professional support needed to grow the institution. The founders of 1913 gave the school a solid financial through ferocious and smart publicity and funding appeals. And, they gave the institution a strong social base on which it could grow and flourish. And, grow it did. In 2013 the school celebrated its one-hundredth year as an educational institution confirming the promise and the wisdom of those early planners.

There are many institutional histories. This abbreviated one is only an introduction. To see other historical resources see the PMSS HISTORIES Guide.

Mary Rogers, wife of Burton Rogers, School Director (1949-1983), and founder of the Environmental Education program at the School, wrote THE PINE MOUNTAIN STORY 1913-1983 for the School’s 50th Anniversary. It remains the best source of history of the school.

Mary Rogers’ small booklet covers the institutional history from 1913-1983, and breaks the history into easily understood blocks of history. Her brief narrative history, illustrated with her own delicate drawings, is an eloquent statement describing the founding years of the institution, the boarding school years and the later Community School. It describes the founder’s plans for the School and the dedication to the founder’s ideas through the years. She says of Pettit and the School

” She [Pettit] had a deep love for the people, and concern for their needs. At Hindman she had already translated the work of Jane Addams and the urban settlement movement into a rural idiom. Now, her thoughts were turning to more isolated, as yet un-served, areas of the mountains.

Traditional schooling was a part of her plan, but she envisaged also a settlement serving a whole community in its economic, health and cultural development. A settlement would not attempt to substitute an outside culture for the indigenous. It would try to strengthen people’s faith in their own heritage, making use of both the mountain environment and their unique traditions as media for learning. It would help people to retain a secure sense of their own worth as human beings.

The new school must have sufficient acreage to supply the bulk of its own needs. It must be less dependent on the slow, unreliable transportation of supplies by ox wagon through almost roadless country.

EDUCATION FOR LIFE

Education was foremost in the mind of Uncle William, and education was at the center of the mission of the two women co-founders of the institution, and all three agreed that this education must be a pragmatic education. It must give the children of the school not only ‘book larnin’, but it must also give them “education for life.” Uncle William described this “education for life” as an understanding of farming practice and a respect for the land that would combine with traditional educational practice. Only then could the total education of the person occur.

Throughout the one-hundred year history of the School, the adherence to an agrarian focus is central to the understanding Pine Mountain’s “education for life.” The pragmatic work engaged by all who passed through the School, emphasized education as a life-long process and one for which they, alone, were responsible.

“Education for life” demanded mindfulness throughout every day. Participation in farming, food preparation, community celebration, woodworking, environmental field work and more. It was an educational idea anchored in a classroom experience, but practiced in every action of the student. Even today, this hybrid approach, solidified by hands-on learning experiences, has proven to be one of the most effective learning strategies, .

An “education for life” is what the poet and writer Wendell Berry describes in his thoughtful series of essays, A Continuous Harmony: Essays Cultural and Agricultural, (1970, 1972), He calls it a kind of “local life aware of itself.” He asserts that this “regionalism is the awareness that local life is intricately dependent, [not just ] for its quality but also for its continuance, upon local knowledge.” Berry dedicated his small book of essays to Ann and Harry Caudill, two Eastern Kentucky locals from Whitesburg, Kentucky, who were intensely aware of their place in the land and who educated many on the fragility of Appalachian land in Night Comes to the Cumberlands (1962). It is a book, in the words of Steward Udall, that is the “story of land failure and the failure of men,” but that in its fatalistic telling called the attention of the world to the lives of so many in the Central Appalachians.

Today as we move rapidly toward ecological and social disruptions, the need to remind ourselves of our responsibility to an “education for life” is even more critical. The education at Pine Mountain has always served up this idea. Pine Mountain Settlement School is a place and an idea that educates for life and that is committed to the literacy of historical community and how that history informs the living community. This commitment to education, both formal and informal, is essential to tying together the land and the people in a fundamental and sustainable eco-system.

In 2015 the mission statement was re-worded, but not dramatically altered when it admonished that the goal of the School was to enrich lives and connect people through Appalachian place-based education for all ages.

“Twenty years ago [1912] Kentucky ranked fortieth in Education among the states of the Union; today she is still fortieth,” reported the Kentucky Education Commission after a two-year study made of education in schools and colleges in the Commonwealth from 1932 to 1934. This was the pre-Depression era and it raised desperate appeals for ideas and help with a school system ravaged by a growing economic crisis. As part of their 1932 study, the state surveyed the students whose lives they were charged to improve. Pine Mountain was visited and queried about educational needs and programs. The surveyors found no shortage of students who were willing to closely critique their school and to make recommendations to their surveyors. Remarkably, the surveyors listened. The educational journeys described by the students served as a model for planning a new course for education within the state. The descriptions of those students are closely detailed in the nearly complete collection of student records held in the Pine Mountain Settlement School Archive Student Records.

In 2010 Kentucky’s ranking in a national survey was 34th in the nation. In two years the state jumped 24 places in the Quality Counts annual report as recorded in Education Week magazine. In 2013, under the Governance of Beshear the state placed an amazing 10th in the national rankings for K-12 education. Something is working. Attention to rural youth was part of the 2013 success.

Read more here: Kentucky Ranks 10th in National Education Survey 2013

The Rural Youth Guidance Institute, earlier called the Pine Mountain Institute, begun by director, Glyn Morris, in 1934 became known throughout the country as a progressive and successful educational model. The Pine Mountain students were “educated for life” and the Depression years in Appalachia and at Pine Mountain Settlement School provided some of the best lessons for that education. The 1930s had many teaching moments that few who experienced them, forgot — student or teacher.

The school still stands as a model for educators who want to “educate for life.” Today, particularly in the field of environmental education, Pine Mountain continues to lead the way in the state of Kentucky across all age groups. Today it educates multiple generations and promotes education as a life-long learning process. A brief 1934, article for The Pine Cone, a school paper written by Pine Mountain students, reflects on the state’s campaign to reform education for its students and where Pine Mountain students fit into that campaign. It demonstrates how the PMSS students were actively engaged in the 1930′ educational planning process

A somewhat unusual feature of this campaign was the enlisting of the services and sympathies of the students themselves by the state. The generous response of the Pine Mountain students to this appeal for comments was characteristic of the sense of community promoted at the school. The school, started twenty-one years earlier gave to the children a willingness to give of their energies that the cause of education may be advanced. They described the influence of Pine Mountain as a real education that “will help us work a little more skillfully, think a little more clearly and act a little more kindly.”

This exploration of farming, food and community engagement at Pine Mountain Settlement School found in the DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH series of essays is authored by one of Pine Mountain’s children, the daughter of one of the School’s farmers, Helen Hayes Wykle. The essays are offered as a contribution to the history of the institution and are filtered through the writer’s perspective. There are many other perspectives.

PHOTOGRAPHS

The photographs of rural life taken by various photographers, during the long history of Pine Mountain Settlement School found in this essay, are derived from a life lived close to the land. Within the faces of the students, the workers, and community families, especially in the children, can be found wonder, stubbornness, joy, fear, defiance, pride, and hope. It is those images combined with some of the personal narratives captured in letters, documents and autobiographies in the archival collection, that the many perspectives may be studied. In these often very personal and literal reflections, can be found a tall mountain of deep wisdom, peace,

humility, despair, determination, hope, anger, but, especially, joy. Yet, some who will view the photographs or read the workers letters about the community will only see the poverty and possibly the exploitation of the local population by “outsiders.” That is not what the school was or is about and on close reading, that is not what the archive ultimately will reveal.

The author John Berger reminds us in And Our Faces, My heart, as Brief as Photos (Berger, 1984) that time and space are inseparable. He cautions us that we must be careful of giving so much to the historical projection of time. He argues, “It is space not time that hides consequences from us.” In the Pine Mountain Valley it is “up Cutshin and down Greasy,” and Wellsley College and “between Hel-fer-Sartin and Kingdom Come,” and Boston and Turkey Neck Bend and New York and Fiesty and Rowdy, that we arrange and rearrangte our critical perspectives.

The words of those who knew and know the land best are sprinkled throughout the following narratives, but it’s the photographs, the images of land and people that most vividly detail the agrarian evolution of the community. The agricultural essence of the unique rural community on the north side of Pine Mountain as explored through the lives of those who worked at Pine Mountain Settlement School and those who lived near-by in the community, is as relevant today as it was when the first vision was shaped by the founders. These are pictures of an education —is in a constant reciprocal stream of teaching. In photograph and text the interactive life along the Pine Mountain range and at the Pine Mountain Settlement School is a reassertion of geographies of hope and how to move between our spaces. It is about finding a personal space in our society and the society finding a space for us.

Pine Mountain Settlement School today continues to be an experiment in rural settlement school practice as well as a model environmental education school. As the School moves beyond its 100th year, the community celebrates with the School. It celebrates the people, the place and an unwavering relationship to the land and to the lessons that may be learned from a close association with its geography in all its variants. People and place, student and land, farmer and field, ecologist and mountainside, are all tied to an educational vision and mission. Today, the school’s programs and its “education for life” ethos reveals an evolving vision and mission. Remarkably, it is a vision that remains fresh and inspiring. No matter where one enters the narrative about the School, the general aim is clear. It is to create critical minds and a sensitive eye when looking at how seasons pass, space evolves, and lives evolve and pass in the valley. It is a narrative that is both sequential and simultaneous, history and historical.

Today our polemics are animated by ideological conflicts, by rancorous politics, and an inability to discern truths. We often lose our close touch with both time and space. History melts our contexts into a sea of irrationality and speed creates a blur with no time for reflection. Often history only surfaces to support some argument or political position that has no verity. We tend to forget in the rush of our lives that there are many truths, many more generations to inspire, and many lessons to learn and many stories to tell that open the pages of our own unique place in time and space.

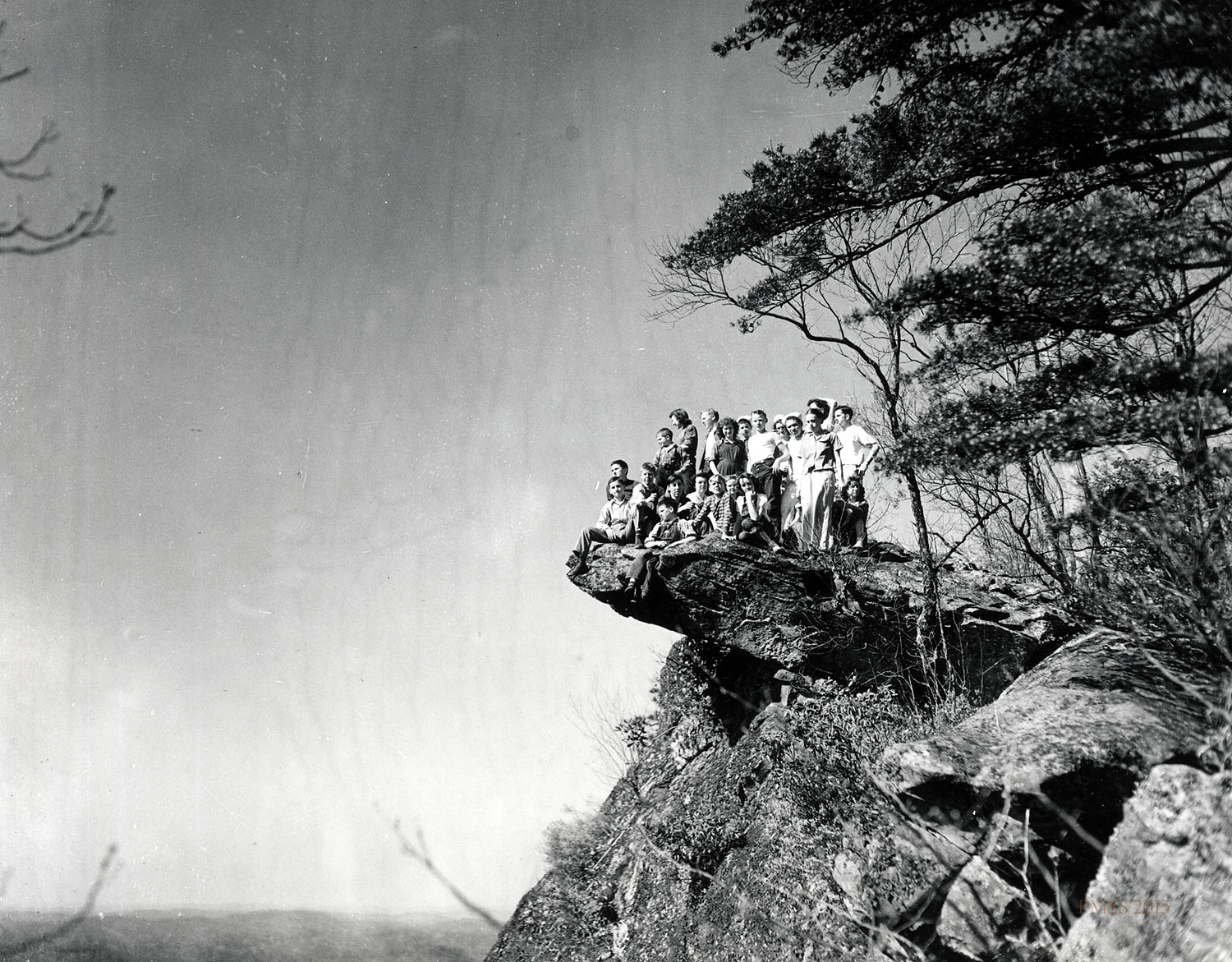

Many of those lessons are found in our relationships, in our historical and genealogical archives, while others may be found on a hike to some remote and quiet place like Jack’s Gap overlooking a slice of life in the long view. When we look out from high places on the expanse of mountains that stretch out below, the view may resemble a troubled sea. The deep green sea, interrupted by the silt, the growing tides of discontent, the green and brown of surface mining — but the air sits close upon that mountain fragrant with fresh pine and vibrant with sunrise and sunset. The trails of Pine Mountain wait to be explored.

Jack’s Gap outing. Arthur W. Dodd Album. [dodd_A_066_mod.jpg]

Helen Hayes Wykle

GO TO: DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH III – PLACE

BACK: DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH I – ABOUT

SEE ALSO: DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH Guide

![[Isaac's Creek?] nace_1_078a.jpg](https://pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/nace_1_078a-1024x672.jpg)