Pine MountainSettlement School

Blog: Dancing in the Cabbage Patch

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH War and PMSS

Many families have carried forward the idea that Eastern Kentuckians have contributed disproportionately to enlistment, casualties, and valor in wartime. One author has noted that this idea has some roots in reality. Alice Cornett, writing in 1991 for the Baltimore Sun noted that the disproportionate number for Appalachians killed while fighting in the wars following WWI did not go unnoticed. Cornett and others have recently suggested that the large numbers of enrollees , the often large number of soldiers from Appalachia, is associated with what some have referred to as the “Sgt. York Syndrome.”

THE SGT. YORK SYNDROME

The syndrome coined by Dr. Steven Giles, a psychologist working for the Tennessee Veterans Administration Medical Center at Mountain Home, is in Dr. Giles’ view both laudatory and troubling. He notes that the syndrome is bolstered by the pervasive idea that the Appalachian soldier is a “good” soldier; that ”Appalachians make good soldiers, and the Army knows it.” This goals- congruence factor, for good or ill, has often found Appalachian soldiers at the front-line of battle and often lauded as the most heroic of soldiers in battle.

Why has Sgt. York today become a “syndrome’ of Kentucky soldiers? Sgt. Alvin Cullum York (December 13, 1887 – September 2, 1964), was a native of Pall Mall, in eastern Tennessee. By most accounts, he has been described as a hero and the quintessential soldier. A rifleman, whose bravery in battle and subsequent award of a Medal of Honor, captured the imagination of a nation. He was immortalized when his life was made into a movie in 1941. Sergeant York directed by Howard Hawks with Gary Cooper as York, was as timely, as it was motivating for many young men who viewed the film. The enrollment for WWII was growing and Sgt.

York set a standard of conduct that almost made serving in the Army a religious duty. York’s exploits which were translated to the silver screen furthered his legend and that of the Appalachian soldier. On the cusp of WWII, York, in the mind of the nation and particularly in the minds of Appalachians, Sergeant York was the model soldier and the “Sgt. York Syndrome” took roots and grew. York’s bravery and his philanthropy now known to all Appalachian young men and to their families following the Great War, became a topic of pride in the mountains and remains so today.

York’s bravery and his philanthropy now known to all Appalachian young men and to their families following the Great War became a topic of pride in the mountains and remains so today. After the release of the film, perceptions grew regarding the fearless nature of the Appalachian soldier. In fact, all the wars since the Great War which the United States has engaged have invoked the name of Sgt. York. In the Appalachian mountains, particularly when recruiters came to enlist soldiers, the name of Sgt. York was often lurking at the back of both the recruit and recruiter’s mind.

Yet, even before York, the Nation had seen large numbers of young men and women from Appalachia step eagerly forward to serve. In one Appalachian county in Kentucky, Breathitt, there were no draftees during the whole of WWI because quotas had been met and exceeded by the general enlistment of county residents.

However, all this patriotism has yielded a grim fact. Data gathered by Alice Cornett should be noted

As a percent of its population, the Appalachian region has sustained higher losses in our wars of the past 50 years than has any other section of the country. West Virginia, the only state designated as wholly in Appalachia, had the highest casualty ratio in both World War II and the Vietnam conflict.

Many of the counties in Appalachian states have seen their young men recruited, volunteered, and serving in war but the propensity to fight in wars has also been associated with the need for employment and the often biting poverty. The same Appalachian counties that sent large numbers to war were often some of the poorest counties. The numbers of Appalachian soldiers is also now matched by a disproportionate number of racial minority recruits. Thus, the Appalachians Blacks, Hispanics and other groups struggling with economic and social challenge often find military recruitment a way into careers and out of poverty. Again, the military recognized that these young men and women will “soldier on” because of their deep patriotism.

[See: http://kentuckyguard.dodlive.mil/2013/03/19/a-patriotic-clan-from-eastern-kentucky-in-the-war-to-end-all-wars-part-one/]

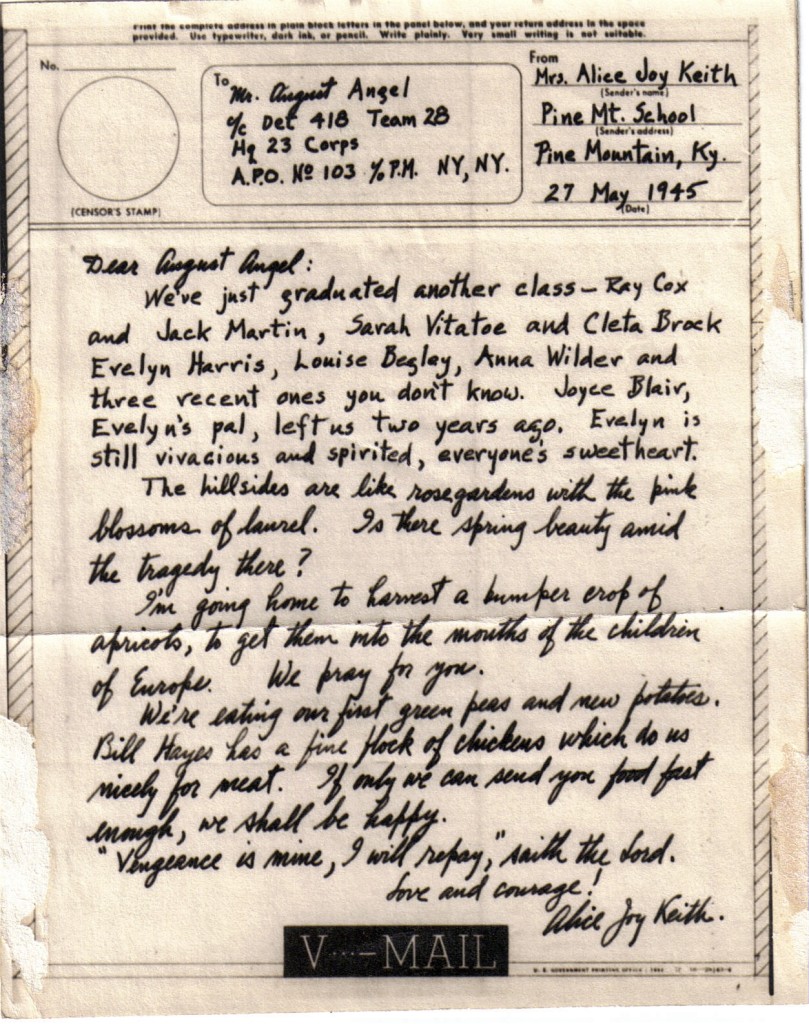

WWII V-Mail letter from Alice Joy Keith to August Angel, 25 May 1945. [Angel WWII_vmail_from Alice Joy Keith. [Angel-WWII_vmail_from-Alice-Joy-Keith.jpg]

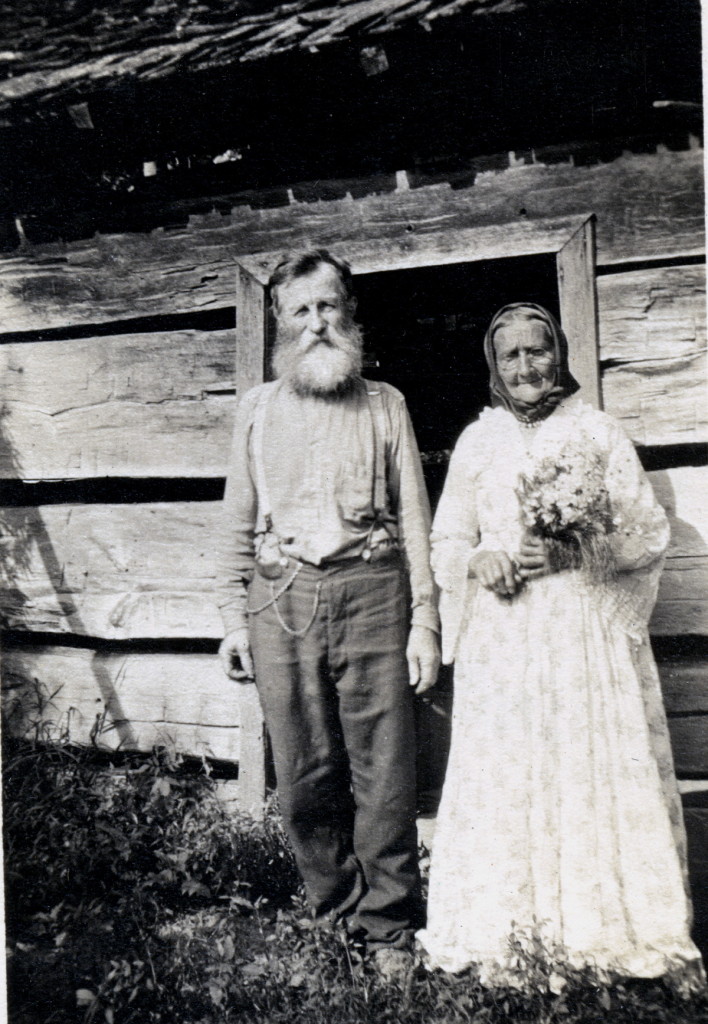

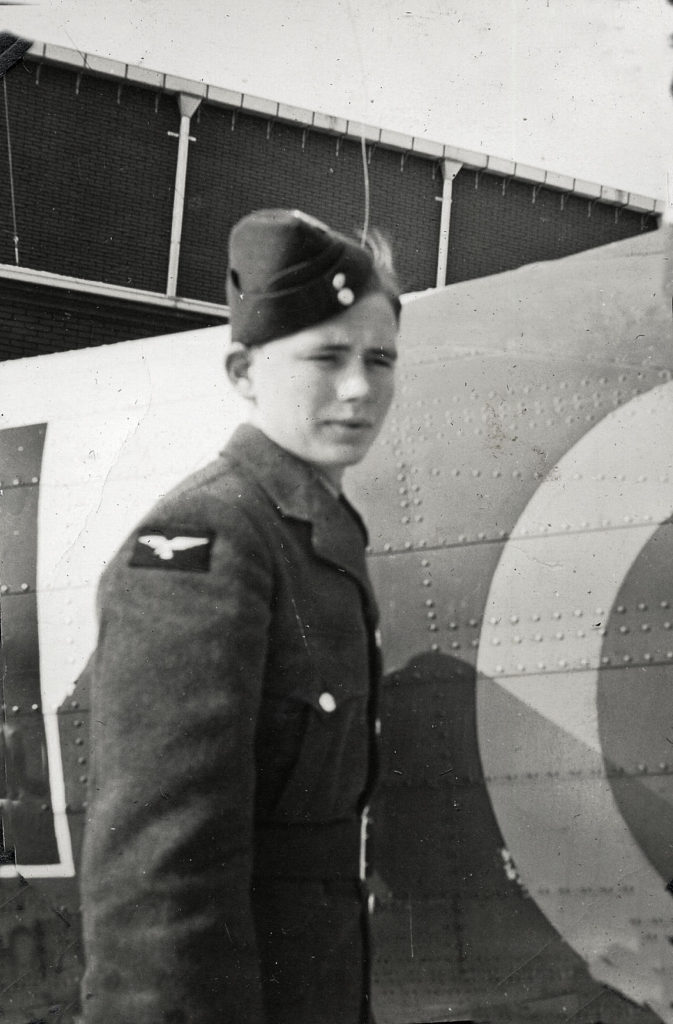

Unidentified PMSS student.

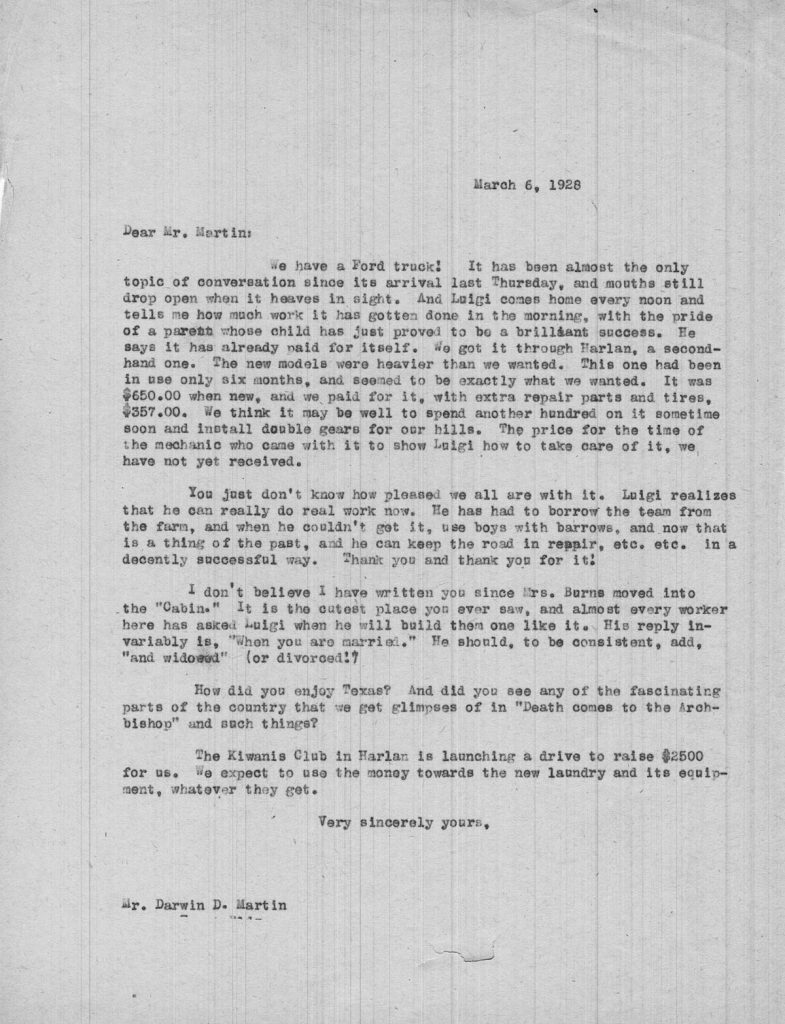

At Pine Mountain, there are many stories regarding the School’s engagement with WWI. As students left to fight in the Great War, the staff also left their positions to fight alongside their students. The School was often challenged to fill critical staff positions as well as maintain a balanced student body. For example, when Leon Deschamps, a Belgian farmer working at Pine Mountain left to fight in WWI early in 1918, he kept in touch with the School and with the children. Deschamps served in the American Expeditionary Forces in Europe in 1917, under the command of General John J. Pershing. He was assigned as a translator (French) and in the forestry department. His presence in the battle abroad was followed with fascination by the whole School. The students regularly held cocoa and rice dinners to save money for the “Belgians in the war” effort.

In reading through the Leon Deschamps Correspondence we are reminded of the discrimination that many immigrants faced following WWI and WWII and today. As a “foreigner” Leon was one of the first members of the Pine Mountain staff to join the WWI war. Yet, he was excluded from many of the opportunities afforded job seekers when he retruned. In some cases, the discrimination came from some of the more “enlightened” educational institutions in the country, though there is little indication that Pine Mountain showed him any exclusions. His talents, determination and the enormous endorsement given by those who worked with him are well documented in his correspondence. Yet, the suspicions ran deep regarding “foreigners” following the war. in the mountains of Appalachian, largely a rural geography, it is no surprise to find see the inclusion of those who knew him that he left legends in all the institutions he touched. Not many of us can claim such legacies.

War, for most of the students at Pine Mountain Settlement, was a distant and somewhat romantic engagement until the soldiers began to return home shell-shocked, lungs destroyed by mustard gas, or, in a casket. Yet, for many staff at the School, war was already a very real experience, and one not to be romanticized.

Perhaps one of the most remarkable impacts of war on Pine Mountain staff is found in the personal narratives of those who came to the School after having served in remote corners of the world during wartime. One of the most harrowing first-hand accounts of war can be found in the staff who were impacted by front-lines of conflict. One of these conflicts, the Ottoman Turk-Armenian conflict witnessed by Dr. Ida and Rev. Robert Stapleton was particularly horrific and is well recorded in a recent book published by their granddaughter, Gretchen Rasch. The Storm of Life: A Missionary Marriage from Armenia to Appalachia, published by the Gomidas INstitute in (2016 tells of the two missionaries horrific struggle with the mass genocide of Armenians in and around Ezerum Turkey.

The Stapletons came to Kentucky in the late 1920s to serve as co-directors of Line Fork Settlement (Letcher County, Kentucky), a satellite settlement associated with the Settlement School. They were particularly well equipped to meet almost any human conflict with experience and compassion following their harrowing experiences in Turkey. The battles around moonshine and the frequent revenge killings of the Appalachians were part of their everyday life on Line Fork in the early decades of the twentieth century. It was a life they often met with humor and compassion, but even more, with understanding. Their early work with the Ottoman-Armenian conflict no doubt brought the petulance of personal and familial battles quickly into perspective.

Another staff member at the School also experienced the Ottoman Turk-Armenian conflict in a more Eastern region of Turkey. Edith Cold was stationed in Hadjin, Turkey as a school teacher for children orphaned by the ethnic war. Her letters and stories regarding the conflict that slowly engulfed the region are equally chilling and capture the severe circumstances that war brings to communities across the world. The trials of Edith Cold were captured in a series of New York Times articles that chronicled her ordeals and her incredible bravery in efforts to keep the children and the staff of the school safe from harm. As genocide ravaged the Armenian populations, workers such as Edith Cold and the Stapletons witnessed horrendous atrocities and placed themselves in harm’s way on a daily basis. Today, those echoes of brave volunteers and their harrowing continue to fill the news and speak more of the inhumanity that lurks in every conflict of border, ideology, and beliefs. The tales recounted by the Stapletons and by Edith Cold of life in Turkey in the first decades of the twentieth century were shared with students at Pine Mountain, more in their models of tolerance, support, and understanding, than in their recounting or bearing witness of war’s inhumanity. There is good evidence that they softened the edges of many hard lives in the Pine MOuntain valley and beyond.

PMSS AND WWII

During World War II the actions of war came closer to the School as communication improved and the radio brought reports of the war closer to home. Great numbers of Staff and students left to join the ranks of soldiers or became support staff to the war effort. During these years communication flowed more rapidly and frequently and the war became a real and present conflict that had little room for romanticizing. The American mind was war-focused in this second world conflict and daily informed through radio.

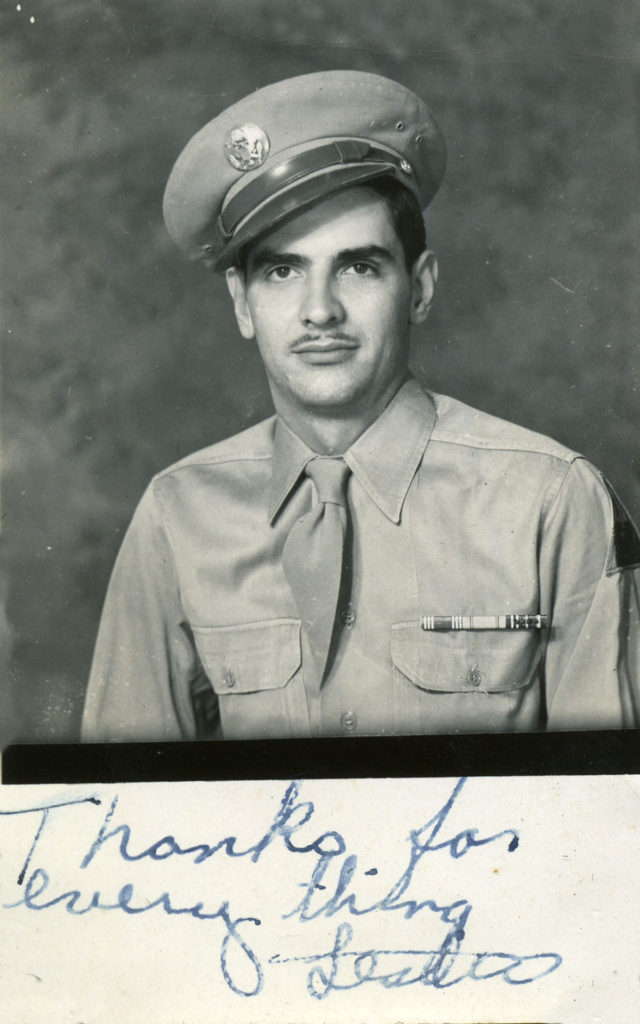

A “Thank you” to nurse, Grace Rood from Lester.

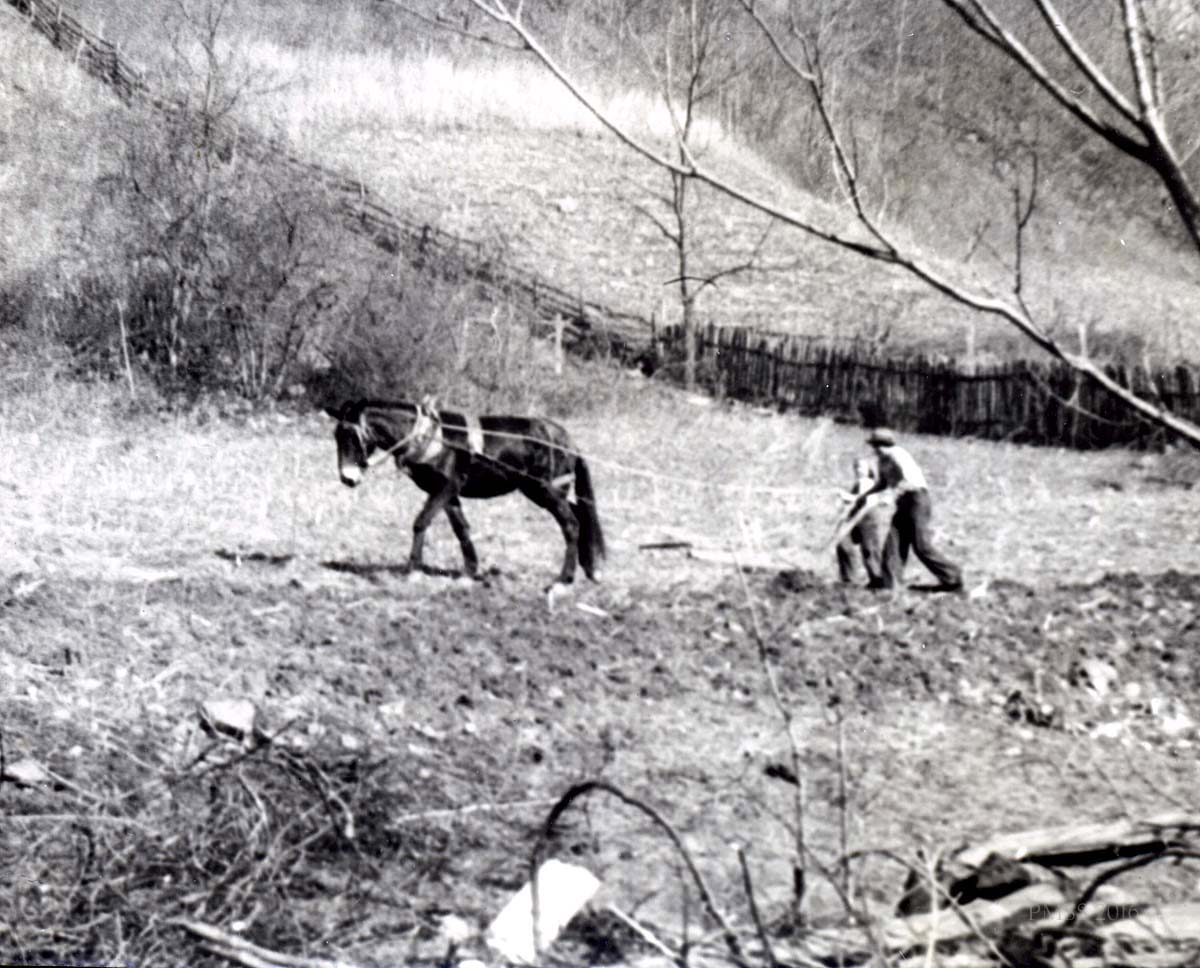

Of all the wars, World War II, possibly had the greatest impact on life at Pine Mountain and in the valley. Many fathers and sons left their farms in the valley to fight in the war. Many young men stopped their classes at PMSS to go fight the war in Europe and women signed on to nurses corps or to the Red Cross or to canteens in Europe to do their share in the war effort. Classes were suspended when key instructors left. Basic supplies could not be obtained for many families and money was tight. Many families could not afford even the smallest tuition. The impact of WWII on the farm was dramatic as rationing began to impact food supplies and families in the community looked to the School for more assistance in farming needs and health issues. Subsistence and rationing became uneasy partners in many families. Rationing, particularly, was a critical issue with all residential schools and particularly the food issues and family loss only compounded the national and personal crises in the Appalachians.

There are many stories related to Staff who had some family relation in either the European or the Pacific theater of war. See especially the important documentation of war efforts by soldiers in Perry County, KY, maintained by Waukesha Lowe Sammons, daughter of one of the county’s soldiers who did not return from WWII. Waukesha, a Berea College graduate, has created a comprehensive website that traces the Military Legacy of the Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen, and Marines, who served from the American Revolutionary War to Operation Iraqi Freedom. Her comprehensive website covers just one eastern Kentucky county — Perry County, but it gives a vivid picture of how many wars impacted the region.

http://www.perrycountykentuckymilitarylegacy.com/

World War II in the Asian theater also directly affected the lives of many of Pine Mountain’s staff and students. For example, the expulsion of staff member Burton Rogers from Yali, the Yale in China School where he was teaching when the Japanese invaded in 1937, brought the family to Pine Mountain. His relocation is another story of severe challenge, hardship, and courage.  Burton Rogers came as School principal in 1941, and later served as the Director of the Pine Mountain Settlement School. His wartime experience was profound and prompted him to a life-time as a conscientious objector. As a member of the Quaker faith and outspoken critic of war for the remainder of his life, Burton and his wife, Mary Rogers, committed their lives to pacification. Mary had learned how to skillfully negotiate conflict when she worked in India and met the pacifist, Ghandi.

Burton Rogers came as School principal in 1941, and later served as the Director of the Pine Mountain Settlement School. His wartime experience was profound and prompted him to a life-time as a conscientious objector. As a member of the Quaker faith and outspoken critic of war for the remainder of his life, Burton and his wife, Mary Rogers, committed their lives to pacification. Mary had learned how to skillfully negotiate conflict when she worked in India and met the pacifist, Ghandi.

The brave and courageous contributions of two Pine Mountain Docotrs, Emma and Francis Tucker and their nurse protegee, Grace Feng Liu brought first-hand accounts to the School’s understanding of the impact of war on individuals. Their stories are remarkable. The Tucker’s heroic struggles during the Japanese invasion of China and their work to raise the standards of health in rural China equipped the couple for the rural medical work they completed at Pine Mountain. The two were at that time long past the normal retirement age. Their story of encounters with the Japanese invading forces and their escape from China when it was overrun by the Japanese, is an inspiring tale of courage and contribution that they shared with the Pine Mountain community and with the students. Grace Feng, a native chinese nurse, was brought by the Tuckers when they departed China and she came for a brief time to the School. It was at the School that she later married T.C. Liu, another Chinese migrant. The story of Grace Feng Liu and TC. Liu is a touching one and can be traced in their own words in the School’s archive. The couple returned to China following the completion of their education in America but were soon caught up in the deadly Communist regime of Mao.

GLYN MORRIS ARMY CHAPLAIN

In 1941, the School’s Director, Glyn Morris left to join the war effort as a military Chaplin and with him went a large number of young men to either enlist or take advantage of the V-12 programs that offered training and educational assistance to capable young men. The letters to staff from soldiers in WWII are important records of the history of the war years at the School, as well as the adjustments that the School made during those difficult years. See for example the Bill Blair WWII Letters and the record of Joe Glen Bramlett, two students at the School.

Another remarkable personal story is that of Frank W. “Unk” Cheney who survived the bombing of Shanghai and imprisonment by the Japanese during WWII at the Chapel prison camp. His experiences as a prisoner of the Japanese was both horrendous and productive for “Unk” who learned the Japanese language and developed an appreciation for Japanese furniture design. He demonstrated how even the most oppressive features of war can be turned to advantage. His aesthetic sensibilities and gentleness brought a different perspective of the Far East to students who had the privilege of working with him at Pine Mountain.

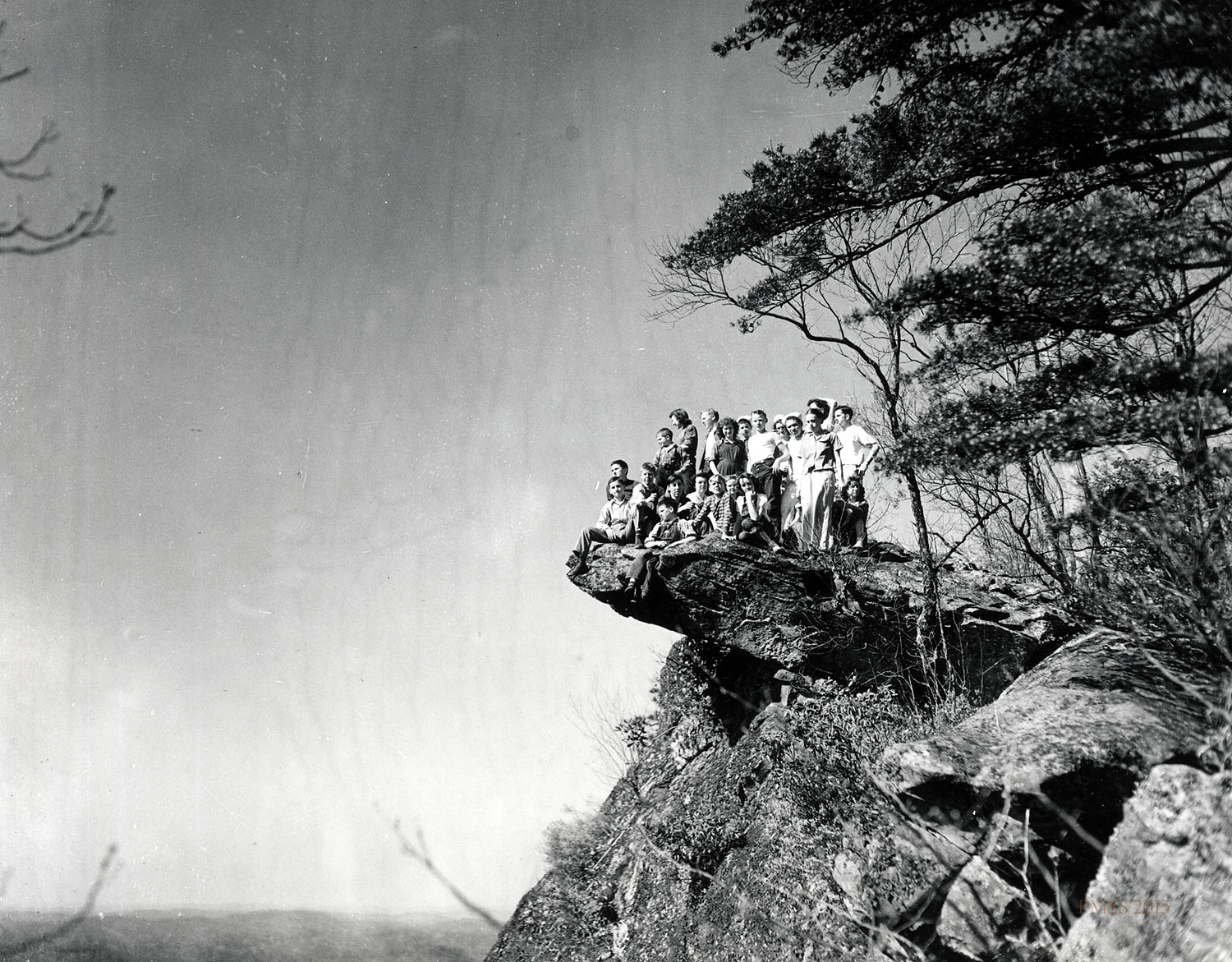

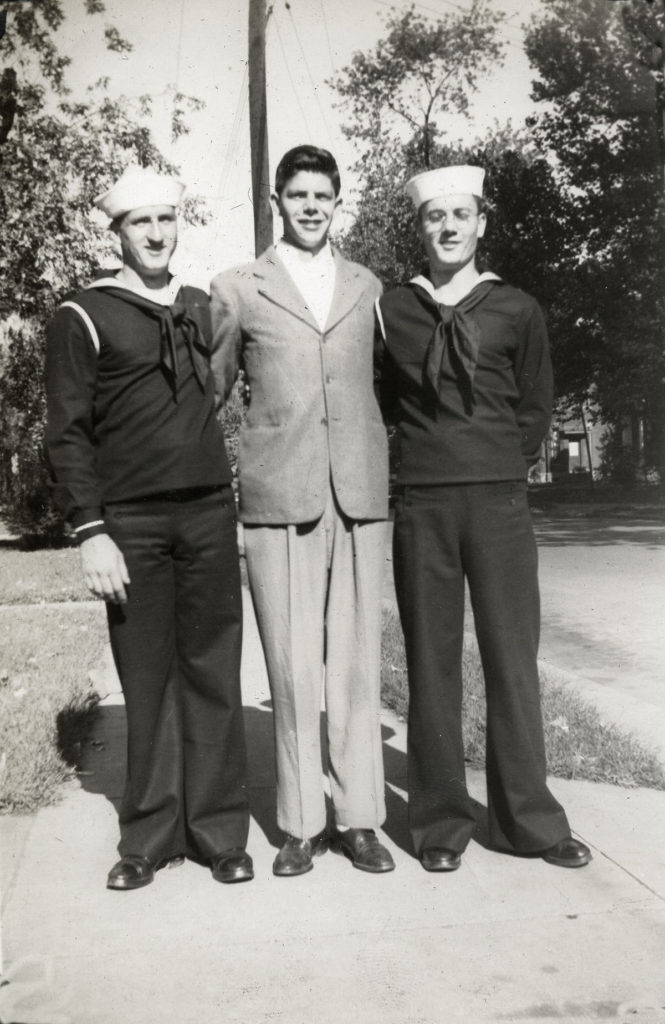

WWII students at PMSS.

Many students felt the call to service in both wars, but perhaps WWII had the most profound effect on Pine Mountain Settlement, as so many young men enlisted that work crews and the work-flow of the institution was dramatically affected.

The three young men to the right are typical of the pride shown by these new soldiers.

Paul Hayes, a student, and later PMSS Director, went to Berea College as part of the V-12 program and later to Duke as a recipient of the same military assistance. Paul saw duty in the Pacific. His brother John Hayes, first signed on as part of the Army Corps of Engineers and later in the regular Army, also going to the Pacific theater to fight. Silvan Hayes, the oldest brother was already in the Army in the European war and was killed in 1943 in France. Enoch C. Hall II, a PMSS student from Perry county left Pine Mountain and joined the Army and served in Hawaii. He was among the many soldiers who were witness to the opening days of WWII when Pearl Harbor was bombed by the Japanese and led to the declaration of war by the U.S. Hall’s barracks at the Honolulu air field were strafed by the Japanese in the opening days of the Pacific war. Joe Glen Bramlett, a student who served in the Army left a large visual record of his years at the School and those in the Army.

Student William David Martin left PMSS in March of 1941 to join the Navy and following his completion of duty wrote a letter to the School saying that he had earlier been overcome by “Navy fever” and would like to complete his degree at the School — which he did.

All these young men served with valor and conviction in WWII. Most came home, but some did not survive the ravages of battle. Their names were placed on a small plaque that once hung in Laurel House. Delicately inscribed and gilded, it now shows its age and has been placed in the Archive of the School.

WOMEN IN THE WARS

[**See: http://kentuckyguard.dodlive.mil/2013/03/19/a-patriotic-clan-from-eastern-kentucky-in-the-war-to-end-all-wars-part-one/#sthash.1NIycerE.dpuf]

There were no women allowed in the ranks of the military before WWI. In 1901 women were able to join the Army Nurse Corps and by 1908, women were allowed into the Navy Nurse Corps. When the US entered into WWI, the ranks swelled in number to around 250 women with approximately 15 drawn from the Appalachian region. Three of the women were from eastern Kentucky and all were graduates of Berea College’s nursing program. **

During WWII there were numerous women from eastern Kentucky and from Pine Mountain who joined the war effort. Two notable nurses who trained at Pine Mountain were Mable Mullins, from Partridge and Stella Taylor. Both young women earned commendations for their war work.

Stella Taylor

Many will agree that Mullins and Taylor made remarkable careers for themselves in WWII. Mable Mullins became a Major in the Army, a rank as high as a woman could go t the time. Stella Taylor contributed nursing services as an Army nurse and gained recognition for her work. Other nurses trained at Pine Mountain were quickly signed on to the war effort. Also, women left the School to provide services or direct support in WWII in jobs that did not require enlistment but that supported the war effort. Generally these jobs were those in industrial support, and/or canteen work.

Many young men in WWII were not drafted but were exempted in order to maintain farms and critical operations on the home-front, or, often they were exempted because they already had multiple siblings fighting in the war. William Hayes was one such student who was retained at Pine Mountain to maintain the farm while three brothers were recruited. His correspondence with his mother, his brothers and with various students who fought in the war is poignant. The sacrifice of his older brother, Silvan Hayes to the war effort in France left permanent scars on his family as the war did for so many families in Appalachia. William’s correspondence with student Bill Blair is extensive and provides a picture of a student’s course through military training and deployment during wartime. The list of enrollees in the war efforts of the 1940’s is a long one. Yet, exemption for most young men from Appalachia was not something that they welcomed during WWII just as it was not during WWI and many of the succeeding wars.

The list of enrollees in the war efforts of the 1940’s is a long one. Yet, exemption for most young men from Appalachia was not something that the men generally welcomed during WWII just as it was not welcomed during WWI and the succeeding wars. It was noble to serve for most men in the community. Within the staff workers at Pine Mountain, the story was often quite different, as many came to the School as conscientious objectors and served their time contributing to the work at the mountain settlement. Two Quakers come readily to mind: Peter Barry and Burton Rogers.

PMSS AND THE KOREAN WAR

The Korean war did not have the same impact on PMSS as did the larger WWII conflict, but it still left its mark on families in the Pine Mountain Valley. As noted by Alice Cornett’s statistical accounting of participation in that war in her 1991 Boston Sun article,

Nine percent of U.S. military forces in the Korean War were from areas of Appalachia, but 18 percent of the Medals of Honor awarded in that war went to the Appalachian soldiers. In Vietnam, they made up 8 percent of our troops and received 13 percent of the Medals of Honor.

[See: http://articles.baltimoresun.com/1991-11-11/news/1991315046_1_appalachian-counties-vietnam-war]

PMSS AND THE VIETNAM WAR AND THE WAR ON POVERTY

At the opening of the Vietnam conflict, Pine Mountain was no longer a Community School site but many of the children who had attended the Community School began to be caught up in the action in Vietnam as they came of age. The most dramatic impact on Pine Mountain of this conflict was the same as that found throughout the country. Families were wrenched apart by conflicting sympathies for the war effort and communities were pitted against other communities as the war dragged on for almost two decades. Coal was often in the news as the resources went to support the energy needs of the growing war effort and families saw both a coal boom and a large out-migration to Northern factories, as in WWII, where work in the military-industrial complex could bring better wages.

Cmdr. Steven Hayes (back row, far rt.). a student at PMSS and crew on the USS Constellation following the end of the Viet Nam War..

In April of 1964. Lyndon Johnson traveled to Inez, Kentucky and sat on the porch of the Tom Fletcher family and declared a War on Poverty. As noted by many, the universities in the Appalachian region were more engaged in naming buildings and honoring the dead than engaging their cultural and economic conscience. A political and economic protest was not high on their agendas as they followed the welfare of family members caught up in the Vietnam conflict. Eventually, however, it was Johnson’s “War on Poverty” that created the largest shock wave on Appalachia, not the fighting in Vietnam. The fall-out from Johnson’s social service programs for the Appalachian region would have an impact far greater than any war fought in foreign lands. Many scholars today remind us that families in the region are still climbing out of poverty that was prolonged by this federal assistance effort. —the War on Poverty. The casualties from the ramifications of the War on Poverty were not just sons and daughters, it was entire families and generations of those families.

Used as a sort of guidebook for the eager volunteers that came into the region, Jack Weller‘s Yesterday’s People (1965) became the cultural window for the Appalachian Volunteer program, an outgrowth of the War on Poverty. Funded through the Office of Economic Opportunity, the Appalachian Volunteers soon found themselves in a cultural war that roughly followed the same timeline as the Viet Nam War and the political differences were often as volatile and acrimonious as the Anti-Vietnam war movement. Accused as Communists, radicals, hippies, elites, subversives, and importantly, “Outsiders,” the Appalachian Volunteers (AVs) came into the region believing that they could make a difference. Two other “outsiders, Glyn Morris, then at Evarts and Myles Horton at the Highlander Center in Tennessee cautioned the new arrivals to respect the cultural differences of the region. Both Myles Horton and Glyn Morris had studied under Reinhold Niebuhr at Union Theological Seminary and Myles admonished the AVs who trained at his center in Tennessee to “…find out what they [people of Appalachia] want you to do and work quietly, and remember: you’re different. They’re not different.” Neibaur’s book, Moral Man in an Immoral Society, made a profound impact on both Morris and Horton and helped to shape both of their worldviews regarding war and each had an antipathy toward a war of any sort. Don West, poet, activist and native of Appalachia was more direct in his cautions regarding the War on Poverty

The Southern mountains have been missionarized, researched, studied, surveyed, romanticized, dramatized, hillbillyized, Dogpatched and [now] povertyized …

By 1970 the Appalachian Volunteers had lost their funding from the OEO and Johnson’s War on Poverty had come to a virtual halt, but not before a number of Harlan County youth had begun to question and rethink the cultural and economic divide in the county and had begun to dialogue with the Volunteers — often against their parent’s protests.

Mildred Shackleford, interviewed by Alessandro Portelli for his book They Say in Harlan County (2011) put it this way

“I got involved in them [Appalachian Volunteers] because I thought they had something different to offer and I wasn’t too sophisticated at that time. I was about sixteen or seventeen years old. I was reading a lot. I was finding out different things. The involvement in Vietnam — I was finding out a little bit of it and I found out that, what the United States was doing in that country, wasn’t something that I could respect; and I hadn’t thought [of] looking at Harlan County in the same way that I looked at Vietnam. That’s one thing I did learn from those people pretty quickly; that in a way we were more like the people in Vietnam than [like] the people in the rest of the country.”

War comes in many forms and is met with an equal variety of responses. Whether it was the Civil War, the War of 1812, the Spanish American War, WWI, WWII, the Korean War, the Viet Nam War, the War on Poverty, or the wars in the Middle East, the people of Appalachia have been there as defenders, patriots, educators, nurses, and very often, leaders, and the lessons of the Pine Mountain Valley have never been far away from their practice and their minds.

*The commentary in this blog is the that of the author, Helen Wykle, and does not necessarily represent the views of Pine Mountain Settlement School. hhw

Resources:

Billings, Dwight B; Ann E. Kingsolver. Appalachia in Regional Context; Place Matters, Lexington, Ky: University Press, 2018.

Niebuhr, Reinhold. Moral Man and Immoral Society: A Study in Ethics and Politics, Louisville, KY: Westminster John Knox Press, 1932.

Portelli, Alessandro. They Say in Harlan County, Oxford/New York:Oxford University Press, 2011. Oral histories taken from families in Harlan County.

Satterwhite, Emily. City to Country circa 1967-1970, Looks at war in the populations of city and country.

Webb, James. I Heard My Country Calling; A Memoir. New York : Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2015. ©2014. A novel about the Vietnam War by Webb, a former U.S. Senator; Secretary of the Navy; recipient of the Navy Cross, Silver Star and Purple Heart and combat Marine. In his words, “…a love story–love of family, love of country, love of service. ” Born in Arkansas but with roots in Appalachia, the Webb family saga spans WWII, Korea and the Vietnam years. Explores the Vietnam War through the over-romanticized novel Christy by Catherine Marshall and the “familiar” depravity of Appalachians as depicted in James Dickey’s Deliverance.

Weller, Jack. Yesterday’s People, Kentucky : University of Kentucky Press, 1965 (reprint 1995) “Mr. Weller presents, with compassion and humor, one of the most incisive studies that have been made of an American folk community. It contains many quotable passages about social classes in America, and about Appalachia in particular.”―Publishers Weekly

See more at: http://kentuckyguard.dodlive.mil/2013/03/19/a-patriotic-clan-from-eastern-kentucky-in-the-war-to-end-all-wars-part-one/#sthash.1NIycerE.dpuf

Kentucky Soldiers in WWII, Harlan County http://usgwarchives.net/ky/military/wwii/harlan.html

See also: http://articles.baltimoresun.com/1991-11-11/news/1991315046_1_appalachian-counties-vietnam-war

![005a P. Roettinger Album. "Country [?] Looking from Uncle John's toward the School."](https://pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/roe_005a_mod-1024x769.jpg)