DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH

Farming the Land Early Years 1913-1930

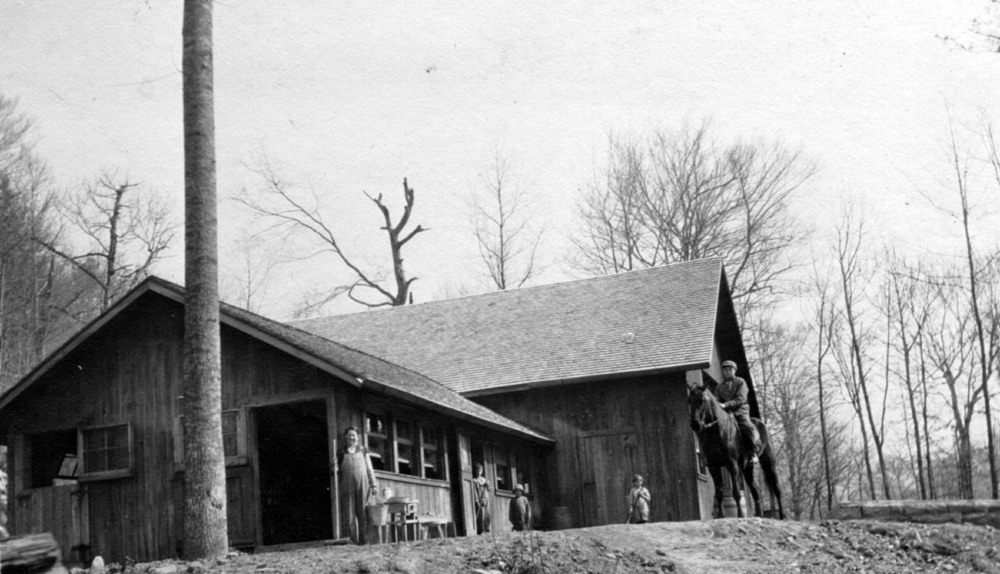

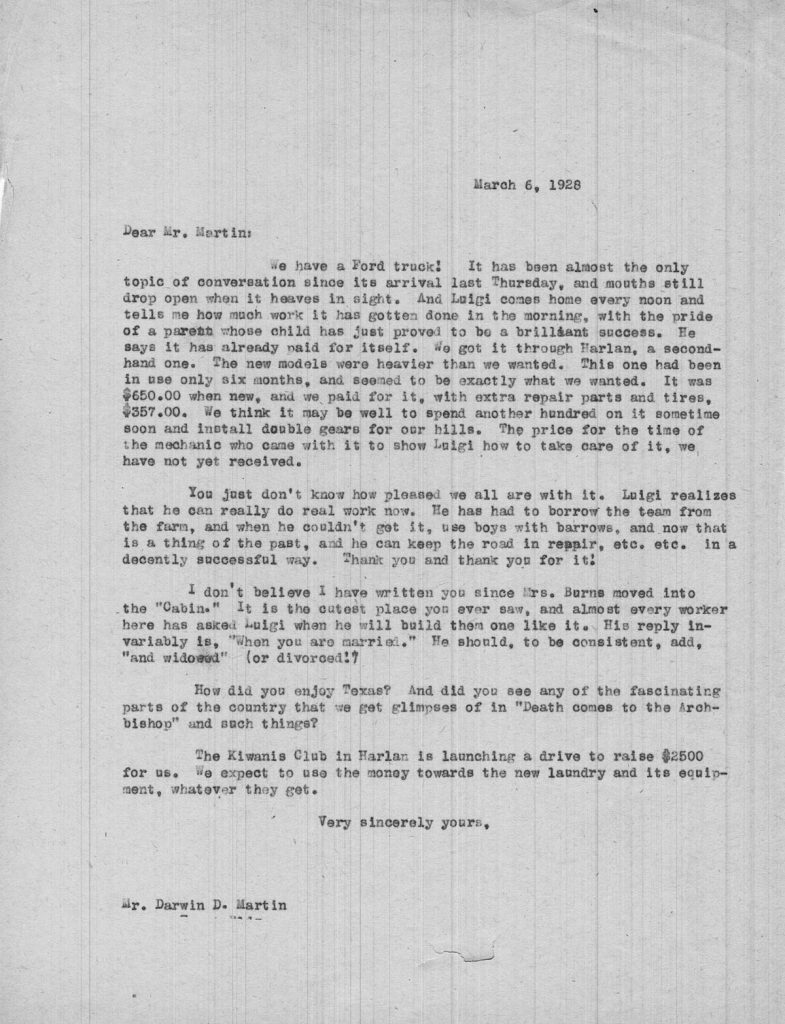

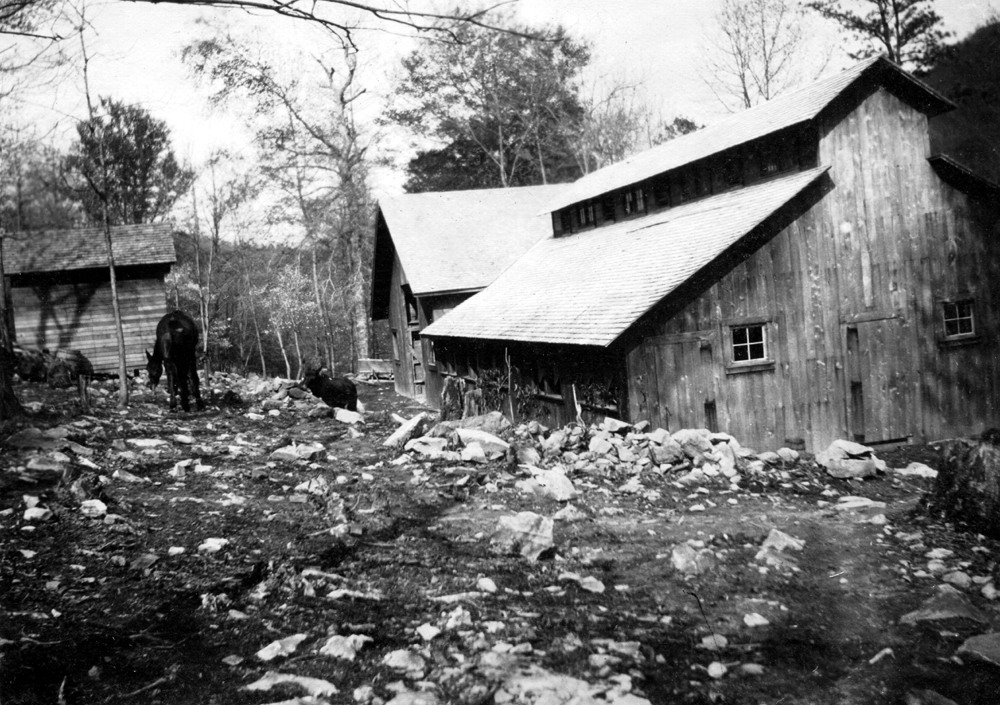

CLEARING THE LAND

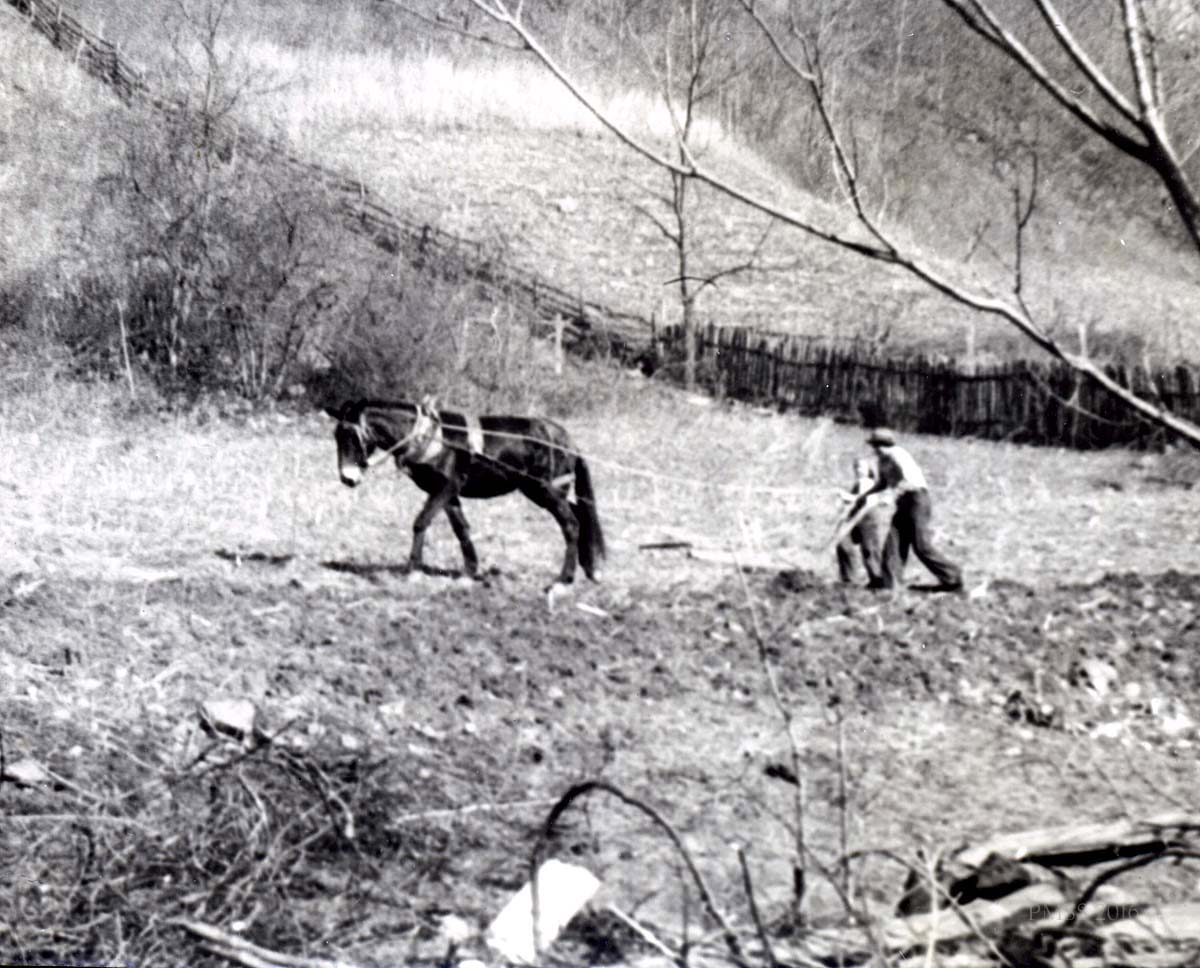

Farmer and Mule. Series VII-52 Children & Classes. [elem_006.jpg]

Katherine Pettit ; Ethel de Long ; Pine Mountain Settlement School farm ; farming ; sustainable agriculture ; William Creech ; Mary Rockwell Hook ; Evelyn K. Wells ; Margaret McCutchen ; creek farmers ; farmers ; Greasy Creek ; Isaac’s Creek ; soil analysis ; livestock ; Ayrshire cows ; poultry ; grazing ; farm managers ; Marguerite Butler ; Farmer’s Cooperative ; University of Kentucky ; Kentucky State University ; Fitzhugh Lane ; Horace D McSwain ; Mr. Baugh ; Gertrude Lansing ; Mr. and Mrs. Clarence Doughtery ; Mr. Morrison ; Boone Callahan ; Harriet Bradner ; Fannie Gilbert ; William Browning ; Louise Will Browning ; Peder Moeller ; Oscar Kneller ; silo ; Darwin D. Martin ; Brit Wilder ; irrigation ;

FARMING THE LAND

Planning for Pine Mountain was very deliberate and where land was involved, Katherine Pettit. co-founder of the School, was a keen observer and a diligent doer. Of the two co-founders, Katherine Pettit and Ethel de Long, it was Pettit who assumed the lead responsibility for the land issues of the School. Under Pettit’s direction, the land was to support the school, but it was also to be a driving force in the school’s programs. In her vision the land would be a source for the agricultural, educational, physical, and emotional needs of the school. The forests, gardens, planting fields, grazing fields, flower beds, —- all received careful consideration under her watchful eye. There is no doubt that the vision for the school’s physical site was always in Katherine Pettit’s mind’s eye but she also called on her excellent on-site help, particularly Uncle William Creech. If she didn’t find her answers in those close-by staff or in the community folk, she did not hesitate to seek outside consultation.

1913 opened with the first visit to the campus of one of the most important of those farm consultants, Miss Mary Rockwell, an architect from Kansas City, Together, Pettit, Ethel de Long, and Hook developed a Master Plan for growth that centered on the topography of the land and the plan was followed, according to Evelyn Wells, (the first chronicler of the school’s history), very closely. Every effort was made to build around the productivity of the land; to use what the land provided and what the topography suggested. Forest lumber, stone from the fields, native plants and flowers, local human and animal labor, native seeds for garden crops and other native resources were called into use. All were considered important to the aesthetics and to the growth of the school and its environs. The remote location demanded that the planners seek local solutions to many of their needs and that they model the best solutions if they were to be both practical and educational in their mission. But, this local focus did not mean the outside world was excluded. It was, in fact, tapped for all it could contribute.

While Mary Rockwell Hook was helping to develop a plan for the land and how the buildings would interact with the landscape, several other consultants were also called upon for direct assistance with farming. James Adoniram Burgess, who was the Superintendent of Construction of buildings, a woodworker and vocational instructor at Berea College, starting in 1901, was well informed about construction and was heavily consulted by Pettit. Pettit also consulted with the Agricultural Department of State University (University of Kentucky), specifically J.H. Arnold, who had written extensively on factors necessary for a successful farm. While Arnold’s focus was on the Blue Grass area of the state he had some sound recommendations for the business side of agriculture. In 1917 he co-wrote with W.D. NIcholls, USDA Bulletin No. 210 “Important Factors for Successful Farming in the Blue Grass Region of Kentucky.” This unique partnering of Burgess and Arnold was evidently very productive. Ethel de Long notes in her May 1913 Letter to Friends, that the consultants, Burgess and Arnold

… were here last week … to give us their advice on the best use of our land and the best disposal of the buildings we hope to have in the course of time.

The progressive ideas of the early founders was not missed on visitors to the School. Margaret McCutchen, a visitor to the School in 1914 and writes:

“The first intimation I had of the School was the foot-log over Greasy, carefully flattened on top by well-placed stepping stones. Here I met with my second surprise, (the first was the beauty of the place) that about this school, only an infant in the wilderness, everything was so ship-shape. Good fences, substantial gates, roads, hitching posts, mounting blocks, the straight furrows of the ploughed fields and even rows of garden patches, wood-boxes on the porches, coat pegs by the doors, and the picturesque stone tool-house to protect the tools and farm implements — all these spell to me in large letters one of the chief articles in the constitution of the school, ORDER.”

View of the school grounds c. 1913-14. Old Log sits at what is now the entrance to the school. The foot-bridge Miss McCutcheon traversed is just opposite the cabin and crosses Isaac’s Creek where it becomes Greasy Creek, the headwaters of the great Kentucky River.

The school’s early years required some clearing of forested land and the re-preparation of older fields cleared by the earliest settlers. In the above view of one corner of the school campus, the land is just being prepared for farming. Efforts to straighten Isaac’s Creek [also known as Isaac’s Run] and to construct a bridge can also be seen. Old Log cabin, the first permanent dwelling on the school grounds is seen to the left in the photograph. Moved to the site for early housing of staff, the structure still welcomes all who visit the school. Today it is the site of the school’s gift shop.]

CREEK FARMERS

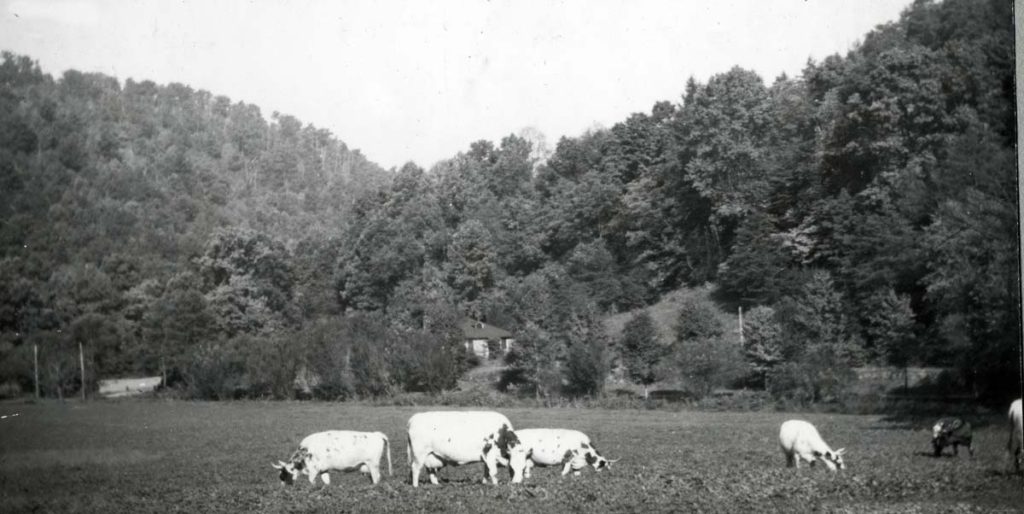

A view down the long Pine Mountain valley in the first decade of the twentieth-century would have revealed the steep hillside farming often practiced in the Pine Mountain valley and the surrounding valleys. In the narrow valleys such as that running beneath the long Pine Mountain spine, the community farmers used as much of their land as they were able to physically cultivate. Often the farms stretched far up the mountainside in a series of random terraces, often following natural contours of the land. The school claims to have introduced terracing but it was also introduced by livestock continually navigating the steep hillsides and by the constant planting and cultivating of corn rows that horizontally followed the contours of the hills. Each year the farmers often advanced up the mountain in search of rich soil as their crops depleted the soil. It was arduous work.

![005a P. Roettinger Album. "Country [?] Looking from Uncle John's toward the School."](https://pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/roe_005a_mod-1024x769.jpg)

005a P. Roettinger Album. “Country [?] Looking from Uncle John’s toward the School.”

While much farming in the Pine Mountain valley was on the sides of the mountain, the practice of farming in the lower areas was often called “creek farming” and the farmers referred to as “creek farmers.” The narrow strip of bottomland in the eastern Kentucky valleys led to this common description in the 1960’s of those who farmed the region. The term was broadened to include the entire family and meant those families who lived only a stone’s throw from the streams of the region. In the small hollow that led into the valley, this geography was often accurate, but the broad slopes of the valley often meant that the farm was much more than a “stone’s throw” from the creek.

Because the developing transportation system often shared the same meandering creek path or sometimes the creek bed itself, the land that could be farmed was further reduced and the families headed for the hills to do much of their farming. This form of subsistence farming, a more common term than “creek farmers”, and the confined transportation corridors, led to the development in the valleys of a kind of continuous and uniformly distributed series of small “centers.” The so-called “Mouth of Big Laurel” is one such central community. The Pine Mountain valley and most near-by valleys followed this pattern of development common to eastern Kentucky.

View of the Big Laurel Community in the second decade of the 20th century. From the Kendall Bassett Album, pmss001_bas010.jpg.

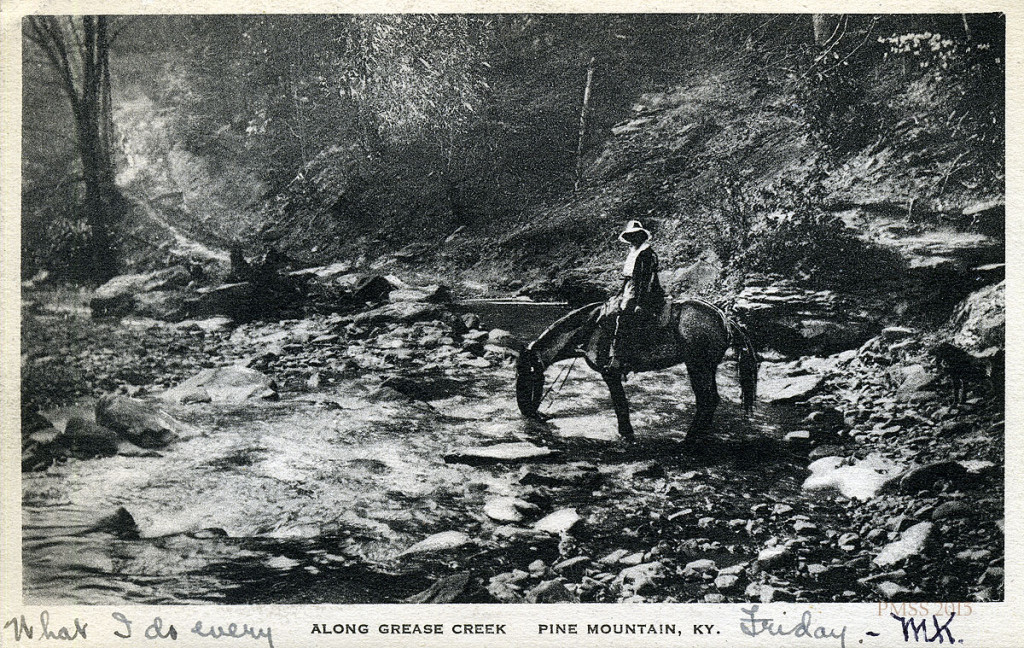

GREASY CREEK

Greasy Creek, a large and stony stream that has its headwaters at the School where Isaac’s Creek flows into Shell Creek, is the largest stream in the immediate area of Pine Mountain. It was supposedly named for the grease of a bear that was killed near the stream. The clear water in the early years supported a variety of aquatic life including abundant bass, brim, and other common stream fish. It was one of the favorite fishing streams in the area and an important source of food for many families. It also served as a water-way to float log rafts down river to the broad Kentucky River and to mills during Spring-tide. Today, it is slowly recovering from mining intrusions and poor sewage control over the years that have left sections of the stream polluted and with diminished aquatic life — with consequential degradation of the entire stream length.

The Big Laurel community on the headwaters of Greasy Creek soon became an important outpost for Pine Mountain Settlement School. As the location for the first of a half-dozen outposts proposed by Katherine Pettit, Big Laurel Medical Settlement was situated on a hill overlooking Greasy Creek and the wide bottom-land and community created at the meeting of Big Laurel Creek and Greasy Creek.

During the early years of the School and before, every piece of land was precious and was sometimes cultivated to the top of the ridge. This extensive cultivation may be clearly seen in the following photograph taken in the first decade of the twentieth century. What appears as terracing is often the result of cattle and farm animal paths that horizontally negotiated the steep hillsides. Greasy Creek flows in the center of the photograph of this country of “Creek farmers.”

FARM CONSULTANTS

Pettit realized that education would be needed to change local farming practices that were both labor-intensive and not sustainable. Following the first consultation regarding the layout of the School and two years after its founding in 1913, Katherine Pettit and Ethel de Long by 1915 had again brought consultants from Kentucky State University [University of Kentucky] to the School to hold a “Farmer’s Institute.” It was open to the full community and brought participants from along the valley and hollows surrounding the school.

Marguerite Butler, an early worker at the school describes the Farmer’s Institute

Four splendid instructors from the Kentucky State University have been here for four days holding Farmers’ Institute. It is a splendid thing for this part of the country and you never saw such interest as the farmers showed. Last night one of the men said it was by far the best meeting he had ever had in Kentucky. Of course mothers, fathers and children came for miles around. Yesterday the school cooked dinner for all out in big black kettles in the open. The men killed a sheep Saturday for the great affair. The talks were splendid on the soil and care of it, the proper kind of food and why, how to raise fruit trees and poultry, which are both easily but poorly done in the mountains. I enjoyed every single speech. Just about four yesterday afternoon we learned that there was a “meetin” down Greasy five miles. Of course we wanted to go, so in ten minutes one of the men and lady instructors, Peg, one of the older boys here and I started off. I bare back behind Miss Sweeny on her horse. We had wonderful fun and the ride at that time of evening was glorious. I stuck on, even when we galloped beautifully. One of the men invited us there for supper so he rode on ahead to prepare supper. They had made biscuit, stewed dumplin’s and chickens, sweet potatoes and all sorts of good things. These professors said it was one of the experiences of their life. We all walked down to meetin’ afterwards in the Little Log School. I succeeded in falling in the creek, so did Miss Sweeney, as we only had to cross one four times. You couldn’t possibly believe what a meetin’ is like unless you hear it with your own ears. I shall have much to tell you. After an exciting ride home over a black, rough road we got here at 10:15, no worse for the wear. [1914 Marguerite Butler Letters]

Miss Pettit’ s consultation and the broad sharing of the findings of the Institute gave not only the farm program at Pine Mountain its first leap forward. but jump-started the educational process for the local community. Pettit believed that the farm was central to the success of the school and that it should be managed by progressive and trained farmers. Her plans were large and her enthusiasm was even greater when it came to farming at Pine Mountain. However, she found it difficult to match her vision with the succession of early school farmers whose early departure from this key position was almost as rapid as annual crop rotation,

Fitzhugh Lane, a young boy whom Pettit and de Long had brought with them from Hindman to help establish a garden and some subsistence farming, was the first farmer at Pine Mountain. He did not stay long and was never designated as “the farmer”. He overlapped with the first designated farmer, Horace McSwain at the School. He came in late 1913 but also quickly left in 1914. McSwain was hired to also serve as the manager of the new saw-mill at Pine Mountain. The dual position was likely unmanageable as the rush to construct new buildings was cyclonic. The following note in a letter to the Board in 1913 describes the clearing of land and the multiple duties of many of the staff:

I wish you could know what important work has been done here through these last weeks. The coal bank has been made been made ready for the winter’s digging, according to the directions of Professor Easton and we are now making a road to it. We have had foot logs laid in many places over the Creek and have built a bridge that ought to last for two generations so that we may haul stone to the site of the school house. Miss Pettit has had charge of most important work In ditching the bottom lands. You will be interested to know why she had to give her time for this, instead of Mr. McSwain. He has had to be at the sawmill all the time, largely because he has not known what minute one of his hands would have to escape to the woods. You see this is not a conventional community and many of our best workers have indictments against them, for shooting, fighting, or even being mixed up in a murder case. Since this is the month when court convenes the men with indictments against them are all afraid the sheriffs may be after them….

Mr.[ ?] Baugh, whose full name has been lost to time, is listed as the designated farmer for the year of 1914. It is unclear whether he overlapped with McSwain or if his tenure as farmer was less than a year. He shows up on the staff listings simply as “Mr. Baugh”. Harriet Bradner is listed for 1915 as a worker on the farm. Leon Deschamps, a Belgian émigré arrived in 1916, hired as the School’s Forester, farmer and teacher. His tenure was to be the longest to date. He briefly left the School to serve in the Great War [WWI] but returned after a year and stayed until 1927. During 1918 and 1919 another woman, Gertrude Lansing is listed as a farm worker, but was not the designated farmer. In 1919 Mr. and Mrs. Clarence Dougherty were hired to work on the farm and charged to pick up some of the responsibilities of Deschamps who was temporarily away. Several staff who had other duties are also listed as farm workers during this time. Edna Fawcett, for example worked as a teacher, a house mother, and on the farm from 1917 – 1919. Many other staff shared farm responsibilities from time to time.

FARM ASSETS AND LIABILITIES

By 1917 the assets and liabilities of the new school are listed as:

Assets:

The original 234 acres of land

125 acres recently given. (Mostly coal and timber)

A coal bank

A limestone cliff

A boundary of timber aggregating 600,000 ft.

A stone quarry

A maple sugar grove

Annual pledges to the amount of $1600.00

An unpolluted water supply

Three dwelling houses

One tool house

Two sanitary closets

Sawmill

Two mules

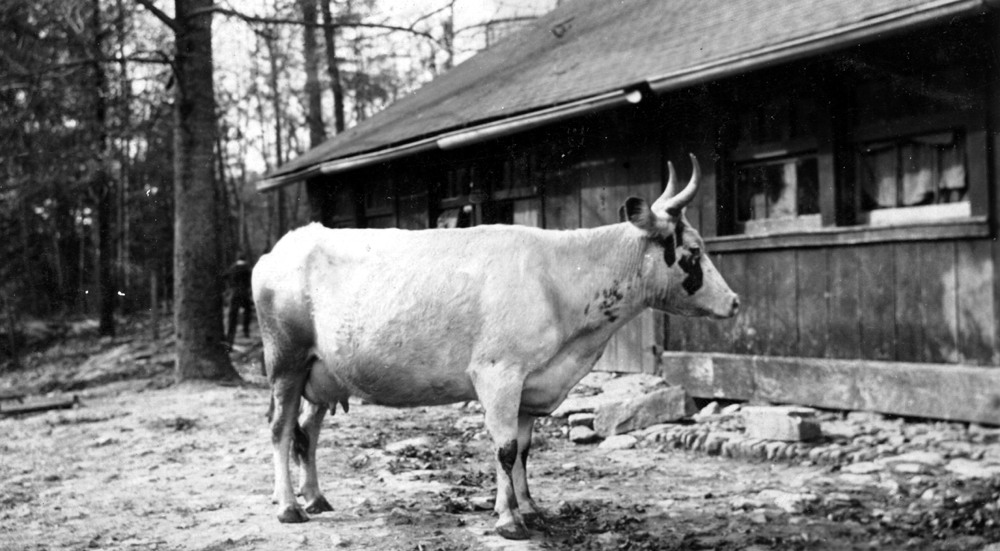

Two cows

One hog and two more promised

Chickens

Two collie pups

Liabilities:

$700.00 a month

FARMERS

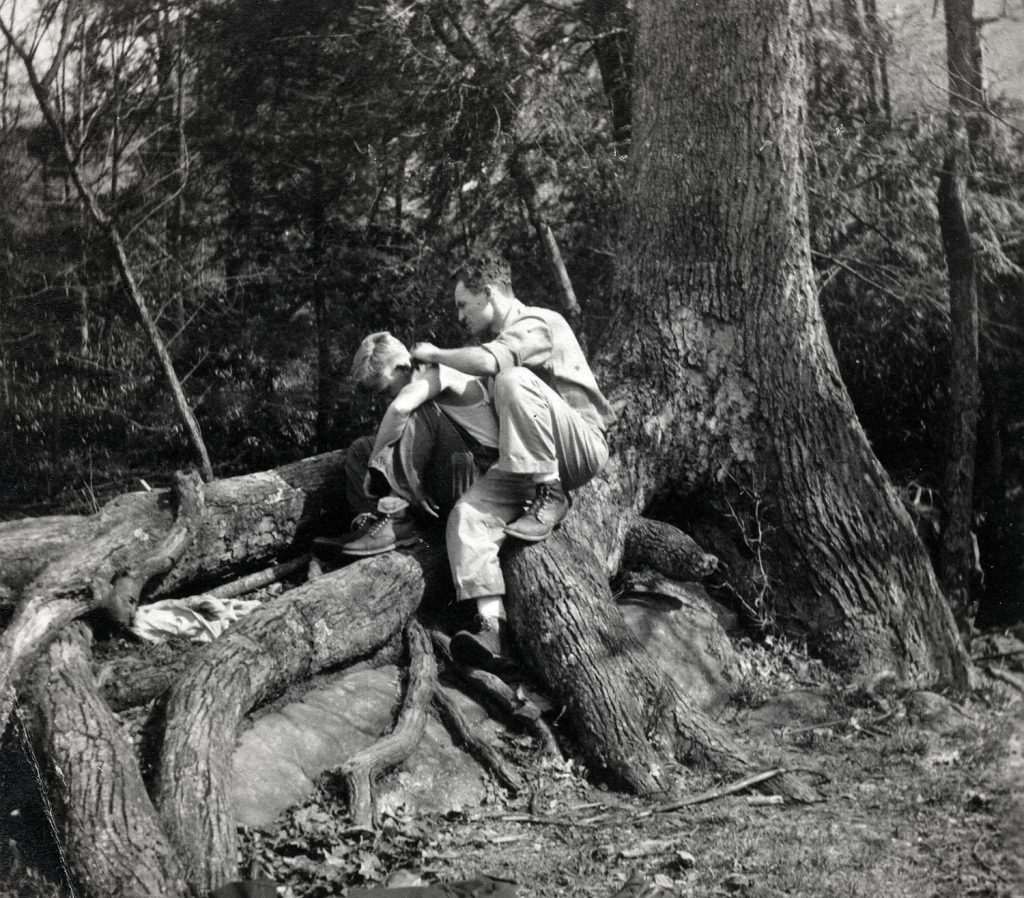

In 1920 Mr. William Browning came to the School as the farmer and stayed for seven years. Later, in 1922-1924, Fannie Gilbert was assigned to work on the farm and assisted Browning. Until Browning, no farmer had lasted more than two years with the exception of Leon Deschamps, whose duties were spread among three positions (forester, farmer, teacher). Miss Pettit’s agenda was a large one and the work to be completed was hard labor and long hours. Farming under Katherine Pettit also required considerable ingenuity and diplomacy in negotiating Pettit herself and the community skepticism of new farming practices. It is clear from the many staff letters that William Browning was a favorite with the women staff. He is described in many staff letters as quite attractive and charming, but someone who “needed to be taken care of.” One of the workers described Mr. Browning as a “buttonless man” who had difficulty keeping his wardrobe together. It appears that many of the women at the school were eager to sew on buttons for the “buttonless man.” He soon took a wife and that ended the button competition.

Browning was also assisted by Leon Deschamps, the Belgian whose training as a forester allowed him to address both the silviculture and farming needs of the school. Browning and Deschamps overlapped from 1920 until 1927 when Deschamps left Pine Mountain following his marriage to May Ritchie, a former student of the School. Under the guidance of Browning and Deschamps, the farm had grown in productivity and, like the previous farm workers, these two farmers largely developed the land according to Miss Pettit’s plan. Deschamps, when he was left in charge of the farm largely followed the planning of Pettit and Browning but when he left in 1928 the direction of the farm went through a series of short-term farmers and some of Pettit practices and vision were set aside. A Mr. Morrison, of whom we know little, followed Deschamps and he was quickly followed by Mr. Boone Callahan who became one of the legendary members of the staff and who was also well known as a wood craftsman. Boone Callahan, one of the many Callahan Family children brought to the School in the very early years and Brit Wilder were among the first Students to come to Pine Mountain. In the 1943 special edition of Notes, “Our Mountain Family,” the contributions of Callahan and Wilder are noted

“… since the days when they [Callahan and Wilder] cut “pretties” for Miss Pettit with their knives, they have never been far away from the life of the school. Boone had special training in agriculture at Berea and at Bradley Polytechnic Institute, and has been in charge of the carpentry department for years. He lives with his family at Farm House. Brit is the truck driver and superintendent of the mine. He is the grandson of Uncle William, is married to a former Pine Mountain student and has a lovely home close to the school.”

Pettit was well read on farming practice and she never ceased her consultation with available experts in the field. During the 1920’s Katherine Pettit had been observing the agricultural progress at John C. Campbell Folk School under their new Danish farmer, George Bidstrup. The Scandinavian farmer, who had been hired to bring Danish farming practice to the Brasstown, North Carolina folk school. Bidstrup was charged to provide model farming for the Brasstown community and had enjoyed considerable success in farming in the North Carolina mountains. Marguerite Butler, a Pine Mountain Settlement School worker who had left Pine Mountain to study in Denmark and had subsequently been recruited to John C. Campbell Folk School by Olive Dame Campbell in 1922. She maintained a lively correspondence with Katherine Pettit following her departure from Pine Mountain and many conversations centered on farming and gardening. Butler married George Bidstrup shortly after she arrived at Brasstown and she was eager to share what she had learned from him about farming with Pettit. When Butler married Bidstrup many local Brasstown practices were passed directly along to the Kentucky school. Intrigued by the Brasstown experiments in farming methods, Pettit went looking for her own Danish farmer and found Peder Moler. Inspired by what she saw at John C. Campbell, Pettit set about to bring the Danish farmer to Pine Mountain where he could introduce Danish agricultural methods to the subsistence farmers of the Pine Mountain Valley. Through Marguerite and her new husband, George Bidstrup, many Danish practices entered the Pine Mountain Settlement School farm program and many Pine Mountain practices were adopted by the community of the John C. Campbell Folk School.

While Pettit eagerly set about bringing the Danish farmer, Peder Moler, to the School, the immigration quotas of the late 1920’s slowed down the immigration process. When the Danish farmer finally arrived at Pine Mountain in 1930, Katherine Pettit had just (late 1930) departed the School as Director and Hubert Hadley had just been hired for a brief year (1930-1931) and was followed by the interim director, Evelyn Wells until Glyn Morris could come as the new Director. It was an unstable time at the School.

In late spring of 1930 the new Danish farmer, Peder Moler, immediately encountered a slew of challenges, not the least of which was resistance to any foreigner changing long-standing mountain subsistence farming methods. As a “furriner” Moler persisted as best he could, and was from all accounts, an energetic and visionary farmer, but one who was “severe” in his demands. His tight “command” of the farm and his crews led to tensions in the workplace. Oscar Kneller, an amiable and seasoned farmer of the Appalachians was quickly hired in July of 1930 and was charged to help Moler. The two were, by all accounts, a good team and they produced record crops. Cabbages and tomatoes were in abundant supply. The surplus of cabbage was so great that it was still feeding the school “until Christmas the following winter.” [Wells, History, p. 26]

Moler and Kneller made many improvements to agricultural practice as well as the grounds of the School but events at the School soon slowed that progress. On May Day in 1932, an unusual act of violence occurred on campus at Pine Mountain. A disturbed young man came to campus, following an argument about a love triangle in the community. He threatened a student with a gun and then killed him — shooting him in the back ass he walked away. Moler, who was present at the event, was very shaken by the confrontation and the shooting and the events following the murder.

Glyn Morris, the new School Director, hired in 1931, asked Moler to accompany him on the arduous hike across Pine mountain to the Big Black Mountain community to deliver the news of the young man’s death to the family. The emotional event, the anguish of the family and the memory of the violence and the cultural differences profoundly affected Moler and he decided on short notice to return to Denmark. His departure left Oscar Kneller singly in charge of the farm.

Kneller was an energetic worker and he immediately set about completing projects begun by Moler and enhancing them. One important project was the purchase of a silo for the barn. The silo was expected to bring down farm costs, particularly for winter feed. Other projects included the further straightening of Isaac’s Creek, particularly in front of the Office and the completion of the pathway and steps to the Infirmary from the lower roadway. In School documents, there is a reference to the “hard surfacing” of roads by Moler, This most likely is a reference to the use of gravel and particularly coal cinders which gave protection to the roads in the winter freeze and thaws. This practical road surfacing and re-use of coal burned in the campus furnaces was a practice Kneller continued.

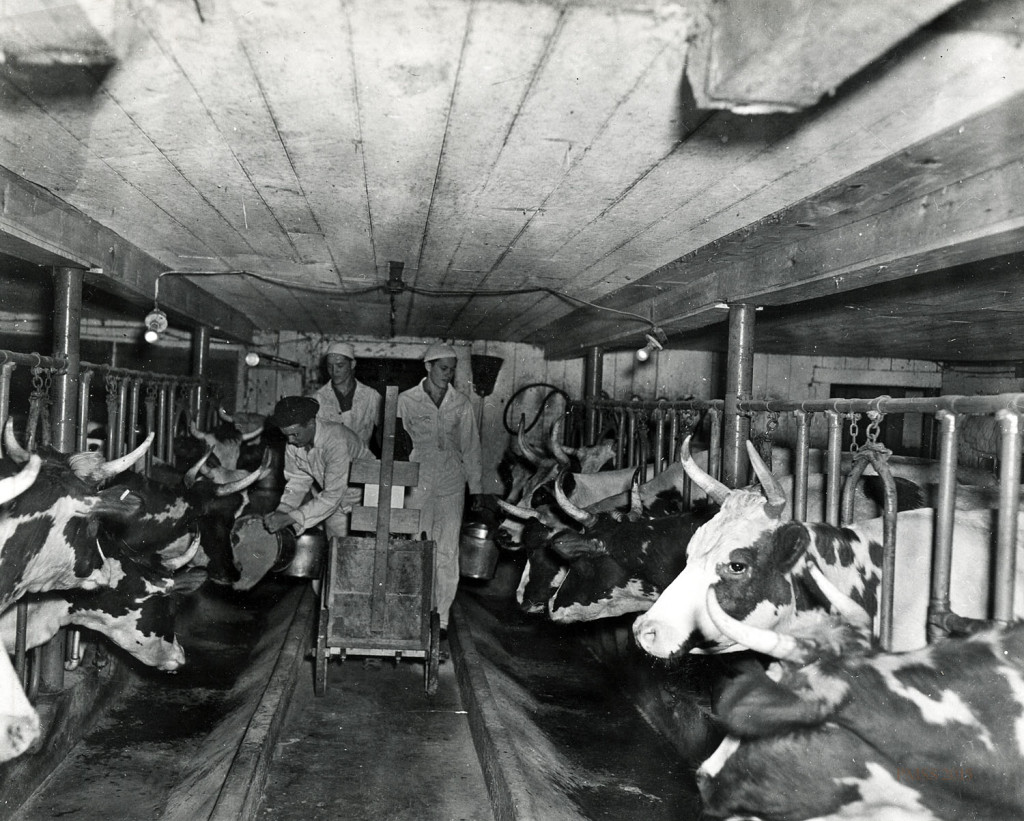

Evelyn Wells, in her unpublished history of the School, describes at length the importance of the addition of the silo and Oscar Kneller‘s role in proving the worth of the new purchase

“Mr. Kneller’s project was the building and filling of the new silo. Up to this time all food for the cattle had been purchased and carried to the school in trucks from across the mountain, and it had been most expensive. There was some disagreement over the building of the silo, but with Mr. Darwin D. Martin‘s backing the silo parts were bought, and in 1932 the farm boys and Mr. Kneller built the silo. The first filling took several days and all the men workers helped the boys. Every evening the progress of the filling was announced in the dining room, and on the last night, when the fodder from the last field had been cut and brought up, the boys and men workers stayed on the job all night. Early in the morning, just at daylight, the task was finished, The silo lacked three rings of being filled, but all the corn was put away.

At the end of November 1931, the cost of the Dairy was $1140,08. At the end of November 1932, it cost $1471.80 which included the cost of the silo, cutter, and all incidental expenses of transportation and erection. Ensilage lasted until the middle of March. No hay was bought. The argument for building the silo was that it could be bought, built, filled and still we could come out at the end of the year with no more expense for the dairy than the year before, leaving the end of the year with the silo paid for. Hay had cost $200 a car plus freight from Putney. It usually was necessary to buy two or three carloads. Thus, there was a saving of about $600. In May 1932 dairy expense amounted to $2469.38. In May 1933 it was only $ 1591.38, plus the cost of the silo $541.55.

Of course, a large amount of the land was given to ensilage and a relatively small amount to a truck garden. But the bottom land was resting in clover since it was practically exhausted. It was replaced with [a] vegetable garden between the creek and the tool house. This record was made in the spring, and at that time a large number of cans of peas had been put away [number not given] the cabbage between 12,000 and 15,000 heads looked well, and corn covered the hill below the chapel.” [Evelyn Wells, History, p. 26]

Crop rotation, another new farm practice, had also been introduced slowly to many local farmers by the school. Some already practiced this technique, having learned by close observation of their soils. The introduction of crop rotation helped to ensure more sustainable farmland for the School and for farmers in the community. Under this practice, crops were given systematic rotation, i.e. cabbage fields were rotated annually with corn and corn with beans, and so on. In fall corn shocks, fodder for animals, often dotted fields where the year before cabbage grew for the school’s extensive canning program. Under the gentle guidance of Oscar Kneller, the majority of the farmers in the area adopted the rotation practice and local crops began to thrive and steep hillsides began to heal and to suffer less erosion.

In a 1920’s editorial in the Jackson Times, the newspaper of Jackson, Kentucky, the editor ruminates that farming

….. for rich and poor, for city and country should stimulate idealism, purpose, action, responsibility, service, brotherhood, true patriotism. It should aim to make better citizens by making better men. And finally, it should recognize the fundamental education in the doing of the common tasks of every day—the education which only needs to be linked with an intelligent vision to make everyday life better and happier. This is our problem in the mountains.

The editor further asks

Is it a mountain problem alone?

Clearly by the 1920’s farming had taken on a role beyond just subsistence and had been integrated into the economic and educational dialogue.

The next farmer, whose history spans some 27 years at the School, was a product of this economic and educational mantra. William Hayes, trained by Oscar Kneller when he came to the School as a student in 1933 became a valuable member of the farming crew. In late 1938 when he graduated from the boarding school at Pine Mountain and was briefly trained at Berea College, he became the next farmer for the School and was retained until 1953. Glyn Morris, hired in 1931 as the Executive Director of the School, had a particular crusade to engage students in industrial training and to meet them where their strengths and interests intersected. He found this in Bill Hayes and also in his appointment of the farm assistant, Brit Wilder, the grandson of William Creech, who had entered the school during its founding years as one of the youngest children ever admitted to the School. Hayes and Wilder were a productive team for many years.

The Hayes years were the longest tenure of any farmer at the School, stretching from 1938 until 1953. This era will be covered in Dancing in the Cabbage Patch V- FARM & DAIRY – THE MORRIS YEARS. Also see: William Hayes.

FARMING AND LAND OWNERSHIP TODAY

Land ownership in Harlan County has changed very little over the years, but ownership of mineral rights has dramatically altered the idea of “ownership” and in some cases the pride that accompanies it. As contracts continue to be drawn up for the new gas resources of the region it is not clear what this will mean for the relationship of future generations to their land, their water and their quality of life, but it is clear that the mountain garden will survive. The transition from subsistence farming to mountain gardens reflects the shift in transportation, food availability, and lifestyle in the Southern Appalachians.

Today, many family lands remain ravaged or vulnerable to the continuing injustice of the Broad Form Deed or “mineral rights” which allows the taking of minerals from lands that were given over by a “broad-form” deed which allowed the owner of the mineral rights to indiscriminately remove their purchased “minerals”. The practice of mountain-top removal is the most indiscriminate form of this “taking.” Unfortunately, the invasive mining practices of today could not be imagined by those who sold their mineral rights through these early broad-form deeds. The broad-form deed returned many families to tenant farmers as coal owners came and scraped off the surface of the farm to remove their mineral — much of this “taking” was bought for as little as a dollar an acre. It was difficult to know in the pre-industrial eras that such easy money would later bring such hard lives.

The quality of rural life in Appalachia continues to shift as new means and practices of exploitation are discovered. The uneasy tenancy of the land in Appalachia has shifted the agricultural focus of many families. Why work the land if it will be stolen away in future years? Why work the land if the grocery store is within driving distance? Why work the land if there is no one who remembers how to manage seasonal crops? Why work the land if the only seeds available are GMO altered and will not come back the following year? Why work the land when there is so much entertainment to divert creativity? The excuses for abandoning the land for local farming and gardening are many. Hard times, however, always seem to return families to their garden and farm. The current downturn in the economy has brought many families back to the land in eastern Kentucky and with that return, many have begun to realize the profit potential of truck gardening, specialized crops, and family savings and the human values growth potential of families in the garden,

Loren Eiseley in his small study of Francis Bacon, The Man Who Saw Through Time, (1961) said that Bacon understood

“…that we must distinguish between the normal course of nature, the wanderings of nature, which today we might associate with the emergence of the organically novel, and, finally, the “art” that man increasingly exerts upon nature and that results, in turn, in the innovations of his cultural world, another kind of hidden potential in the universe.”

I would argue that a dance is better than wandering and it seems that dancing works best with a partner.

GO TO:

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH I – GUIDE

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH – ABOUT

SEE ALSO:

FARM and FARMING Guide

FARM Guide to Resources

FARM LIME KILN Processing

![005a P. Roettinger Album. "Country [?] Looking from Uncle John's toward the School."](https://pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/roe_005a_mod-1024x769.jpg)