Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 27: Scrapbooks

Scrapbook Before 1929

William Aspenwall Bradley

“The Women on Troublesome”

1918

Illustration by Walter Jack Duncan for “The Women on Troublesome” By William Aspenwall Bradley printed in Scribner’s Magazine, Vol. LXIII, March 1918. [troublesome__012a.jpg]

SCRAPBOOK BEFORE 1929: William Aspenwall Bradley “The Women On Troublesome” 1918

TAGS: Scrapbook Before 1929, William Aspenwall Bradley, “The Women on Troublesome”,1918, Walter Jack Duncan, illustrators, Katherine Pettit, Ethel de Long, May Stone, Troublesome Creek, Southern Appalachian Mountain, literacy, Appalachian settlement schools, moonshine, rural education, Berea College, William Goodell Frost, William A. Bradley Literary Agency, Lucy Furman, Hel-fer-Sartin, KY, preaching, religion, quilts, homespun, weaving, “poor mountain whites”, Knott County, KY, Hyden, KY, Scribner’s Magazine, Harper’s Magazine, Paris, France, WWI,

THE WOMEN ON TROUBLESOME

By William Aspenwall Bradley

Illustration by Walter Jack Duncan

The following note was attached to the clipped article found in the “Scrapbook Before 1929”:

This article, probably taken from Scribners, is of uncertain date but was printed before Miss [Katherine] Pettit left Hindman to found Pine Mountain School. Mr. Bradley is the author of a number of stories and poems — among them a volume of poems, “Old Christmas and Other Poems.”

Mr. Duncan, the artist was the brother of Mrs. Smily Jack Goldenwaite of Jackson Heights, N.Y., a contributor to Pine Mountain. Mr. Duncan died about four [five?] years ago in N.Y.

Both gentlemen spent a good deal of time in the mountains and visited the site of P.M.S.S. Mr. Duncan told an interesting story of how he and Mr. Bradley were advised to be inoculated for typhoid fever. Mr. Bradley was and it made him most uncomfortable for several days. Mr. Duncan forgot about it. But, Mr. Bradley was the one who took typhoid — a severe case.

Alc [?? Alice Cobb]

WILLIAM ASPENWALL BRADLEY

The article was, in fact, from Scribner’s Magazine, Vol. LXIII, and dates from March 1918. It is based on the work of two young men who had developed an interest in the region of the Southern Appalachians and who received a commission to travel in the area in 1913, apparently before Katherine Pettit and Ethel de Long left to begin the Pine Mountain settlement. The observations date from the earlier time-frame.

William Aspenwall Bradley and the illustrator of the article, Walter Jack Duncan, received a commission from Harper’s Magazine to go to Kentucky in 1913, where the two spent nearly the full year writing, gathering drawings, and accounts of the history of the state. The visit to Hindman seems to have been particularly memorable and this later (1918) article, recounting their visit, is one of the best early accounts of the origins and the developing rural settlement school movement in eastern Kentucky. The article is especially important to the history of Pine Mountain Settlement School as it details the earlier work of Katherine Pettit, Ethel de Long, May Stone and the other founders of Hindman Settlement, in Knott County near the town of Hyden, Kentucky the contributed to Pine Mountain’s development.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

William Aspenwall Bradley, was born on February 8, 1878, in Hartford, Connecticut. He was an 1899 graduate of Columbia University and continued his studies there through 1900 when he received a masters degree in English. Following Columbia, Bradley began reviewing books for the New York Times and pursuing his own writing career with a book about William Cullen Bryant for the English Men of Letters series. He was also a translator and had a special interest in language. He is well-known for his writings on the Appalachian region and may have been attracted by the unusual dialect of the mountain people, as mountain dialogue is frequently quoted in his Appalachian writings. He most likely came to Southeast Kentucky through contact with William Goodell Frost, President of Berea College, with whom he had earlier corresponded.

Bradley and Duncan spent most of 1913 in Kentucky on a commission from Harper’s Magazine which had found a large audience for Appalachian stories and the romanticized and local color accounts of the mountain folk. While Bradley opened his “Women on Troublesome” article with remarks about the iconic gun culture of the mountains and the feuds that made life in the region precarious, he provides a graphic description of the lives of the women who sought to bring some civility to the feuding and some assistance to families who were desperate for the education of their children.

Bradley followed his work for Harper’s as art director and literary adviser to McClure, Phillips & Co., and was later associated with the Boston Herald, American Magazine, Delineator, and The University Press but never lost sight of the needs of rural America.

WALTER JACK DUNCAN, ILLUSTRATOR

Both William Bradley and his artist friend, Walter Jack Duncan, were soon drawn to Europe by the events of WWI. Duncan, who was born in Indianapolis, IN, in 1881, had studied at the Art Students League in New York City with John H. Twachtman, an artist well-known for his landscape painting and draftsmanship. Duncan became a consummate pen and ink artist and his skills brought him to the attention of popular magazines such as Scribner’s. McClures, Century Magazine and Harper’s Magazine and a recommendation as a War Artist for the United States Army. Duncan left a rich legacy of illustrations of the Great War and also a record of his growth as an artist during the war years.

Bradley also served in the war and while on leave in one of the many households that offered comfort to American soldiers serving abroad, he met Jenny Seurreys, the daughter of a French textile mill owner. Their common interest in literary efforts led to their marriage and the forming of the “William A. Bradley Literary Agency” which had offices in Paris and the U.S. The Bradley’s represented mostly American, English, and French authors, and counted Ford Madox Ford, James Joyce, Gertrude Stein, and Richard Wright among its numerous clients. The Bradleys were essentially the face of publishing in Paris in the 1920’s and their “salon” entertained the notable Paris circle of writers including Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, André Malraux, Gertrude Stein, Alice B. Toklas, and F. Scott Fitzgerald. William Aspenwall Bradley died in 1939 but his wife Jenny continued to head the Literary Agency until she died at the age of ninety-seven in 1983.

The following article carries some of the stereotypes often seen in the era of “picturesque” and “local color” writing — and even today, but the author has an ear and an eye for the region and the people that sheds light on the social needs and the urgency of access to education. He also captures the stubborn native sense that frequently accompanies a clash of cultures and sometimes informs them all..

“Well, we allowed that you uns as knowed how had come to show us uns as don’t, but you hain’t.”

GALLERY: Scrapbook Before 1929: William Aspenwall Bradley “The Women on Troublesome” 1918

- Bradley, “Women on Troublesome,” 1898. p. 315

- Bradley, “Women on Troublesome,” 1898 p.315

- Bradley, “Women on Troublesome,” 1898. p.316

- Bradley, “Women on Troublesome,” 1898. p.317

- Bradley, “Women on Troublesome,” 1898. p.318

- Bradley, “Women on Troublesome,” 1898. p.319

- Bradley, “Women on Troublesome,” 1898. p.320

- Bradley, “Women on Troublesome,” 1898. p. 321

- Bradley, “Women on Troublesome,” 1898. p.322

- Bradley, “Women on Troublesome,” 1898. p.323

- Bradley, “Women on Troublesome,” 1898. p.324

- Bradley, “Women on Troublesome,” 1898. p.325

- Bradley, “Women on Troublesome,” 1898. p.326

- Bradley, “Women on Troublesome,” 1898. p.327

- Bradley, “Women on Troublesome,” 1898. p.328

TRANSCRIPTION: Scrapbook Before 1929: William Aspenwall Bradley “The Women on Troublesome” 1918

p. 315

THE WOMEN ON TROUBLESOME

By William Aspenwall Bradley

Illustration by Walter Jack Duncan

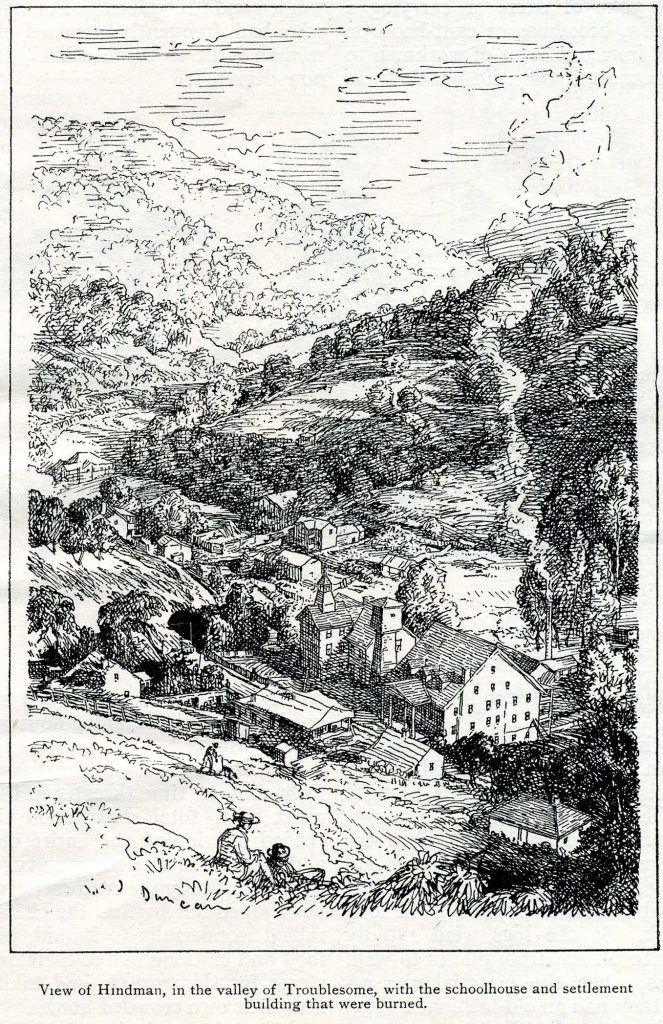

There are still places in the Kentucky Cumberlands like Kipling’s “East of Suez.” Not many years ago the little town of Hindman, in Knott County, at the forks of Troublesome, was one of these — noted for “the meanness of the maneuvers of the citizens.” Such government, as existed, was often a government of outlaws for outlaws. Shortly after the town was started, some thirty years ago, Claib Jones, coming over from the Beaver Creek country, got himself elected jailer, turned the log jail into a fortress by cutting loopholes between the logs, and armed his “prisoners.” Later, both this building and the court-house were burned in the course of the fierce feuds with which the town was torn, and the schoolmaster was more than once forced to sit up all night with his rifle across his knee to keep the school from sharing the same fate.

During the session of Circuit Court, which was held four times a year and lasted a week, the school was always closed, and the older boys, given shot-guns, were sent out to patrol the streets thronged with long-haired desperadoes. During this prolonged reign of terror, armed bands would frequently ride in and shoot up the town, while “good citizens” took to the hills, and women, grabbing their children, sought shelter under beds and houses.

“Whare d’ye think you’ve come?” asked a woman of a preacher who came to hold a service in a similar community. “This air the hell o’ Kaintucky! They hain’t nothin’ but a whoop and a shout

p, 316

and a cuss-word along this here branch all night!”

It was to a similar center of excitement at the forks of Troublesome that two remarkable women from the old settlements came in the summer of 1900. One of them, Miss Katherine Pettit, of Lexington, had made her first visit to the mountains just five years before. Her motive at that time had been mere curiosity. It was in 1895, when the papers of the entire country were filled with sensational accounts of the French-Eversole feud at Hazard, in Perry County, and she was eager to see what sort of place it was, in her own supposedly civilized common-wealth, where the people seemed to spend most of their time trying to shoot one another from ambush. So she organized a party of women and rode up with them into that wild and remote region on horse-back.

Whatever romantic notions they may have had concerning the haunts of these fierce “highlanders” were soon dispelled. They found Hazard a straggling village that lay along the edge of low cliffs above the mud-flats of the shallow Kentucky River, and the families of the feudsters — Americans of unimpeachable pedigree, descendants of pioneer woodsmen and Revolutionary soldiers speaking the language of Shakespeare and singing old ballads straight from the pages of Percy’s “Reliques” — living for the most part in the crude pioneer conditions of a hundred years earlier.

They arrived just too late to see the smoke curling from the muzzles of the guns that laid low the last important leader of the Eversole faction and thus ended the feud. But the town was still in a state of intense excitement from the assassinations and the pitched battles in the streets, and the people, naturally shy, were inclined to look askance at strangers. At the “hotel” the landlady said she was sick and did not want to take them. But she finally agreed to let them have rooms if they would do their own cooking.

One morning, while they were thus busily engaged, a woman slipped into that kitchen and stood some time watching them make biscuit[s]. Presently she ventured timidly to ask them a question. Receiving little attention, she turned to go, saying:

“Well, we allowed that you uns as knowed how had come to show us uns as don’t, but you hain’t.”

p. 317

That was the call that came to these women of the rich and aristocratic “Blue Grass” on their “road to Damascus.” It had never occurred to them before that they might do anything to alleviate the poverty and suffering that so appalled them. Now their idle curiosity which had brought them to the mountains was suddenly transformed into an intense desire to render some assistance. And one of them, at least — Miss Pettit — returned home with a strong resolve to bring aid from her own people in the “level country” to the mountain remnants of that old pioneer race from which they themselves were descended.

It was however not until 1899 — four years later — that she was able to accomplish anything. Then she went back to Hazard, under the auspices of the Kentucky State Federation of Women’s Clubs, with a staff of helpers,* to inaugurate the first experiment in rural settlement work ever made in this country — or anywhere else in the world, for that matter. It was so successful that the fame of “the women,” or “the quare women,” as they at once came to be called, rapidly spread abroad and attracted visitors from distant parts of the mountains.

Among these was a man eighty years old, who had walked all the way from Hindman, twenty-five miles beyond Hazard, in the remote back country. Uncle Solomon Everidge deserves to hold an honorable place in any account of the awakening of eastern Kentucky. In appearance, he conformed to the old hunter and trapper type even then fast disappearing from the mountain. He wore homespun trousers and a white home-woven shirt of flax, and he was both bareheaded and barefooted — peculiarities of attire that he explained on the ground that “the Lord had given him plenty ha’r, so he didn’t need no hat,” while his heels were so hard he could crush chestnuts out of the burr without feeling it!

For the rest, his aspect was patriarchal and imposing. He was tall, straight, and still strong-looking. He had a massive head, with thick white hair and heavy eyebrows, under which his fine dark eyes shone out with an expression of remarkable intelligence and nobility.

“When I was jest a chunk of a boy

p. 318

livin’ on Troublesome,” he said, “and hoein’corn on the steep mountainside, I’d look up Troublesome and down Troublesome, and wonder if anybody’s ever come in and larn us anything. But nobody ever come in, and nobody ever went out, and we jest growed up and never knowed nothin’. I never had a chanst to larn anything myself, but I got cillern and grandchillern jest as bright as other folkses’, and I want ’em to have a chanst.”

It was to get them this chance that the old man had taken his long walk from “yon side the mountain.”

“Times is a-gittin’ wuss and wuss,” he continued. “When I was a boy I was purty bad. The next generation was wusser.” Then pointing to a baby whose mother, standing near by, was fanning it with a white turkey wing, he asked: “What will this gineration be unless you women come to Hindman and help us?”

When he returned he got those of his neighbors who could to write and make the same demand. All winter “the women” were bombarded by these letters. The appeal was irresistible. They yielded. And the following summer they set forth for Hindman.

II

It is a journey of nearly fifty miles from Jackson, Breathitt County (then the end of the railroad), to the forks of Troublesome, and the roads were terrible. Except where they crossed the steep divides by sharply ascending and descending trails, they lay right in the bed of the shallow streams, over black seams of coal in broad ledges of crumbling shale, and were strewn with mighty boulders. Between the steep mountain walls covered with waving corn-fields, and through the deep forests of oak, poplar, beech, and hemlock, “the women” traveled slowly in springless wagons that bumped heavily along and became mired from time to time in deep mud-holes or treacherous quicksands. The trip took two days, and they spent the night on the road in a house where a young girl held a smoking lamp for them while they undressed.

Circuit Court was in session when they arrived, and the court-house was crowded

p. 319

with men listening to a political speech. A boy ran in.

“The women who are aimin’ to live in tents all summer are comin’ over the hill!” he cried.

Then the preacher explained to the people who they were and why they were coming.

“That’s the best news we’ve ever heard in Hindman!” shouted a mountaineer, throwing his broad black Stetson up into the air, and he received more applause than the political speaker.

“You gals ain’t aimin’ to live in them cloth houses, air ye?” a man inquired anxiously when he saw the tents “the women” had occupied the preceding summer at Hazard. “Hit don’t look like hit would be safe, nohow, the way the bullets comes a-flyin’ round here sometimes.”

But they pitched their camp high above town on a steep hillside, and there nights, as they tried to sleep, the sound of shooting would reach them from the street below, mingled at times with that of shouting from the church.

One morning a dozen young men climbed the hill to the camp. Some carried rifles, the rest revolvers in their shoulder holsters. Their spokesman stepped forward when he saw Miss Pettit standing in the entrance to a tent.

“Uncle Solomon says you women hope to have a peaceful summer,” he said, somewhat sheepishly. “Well, we fellers allowed we’d see you had peace if hit took steel bullets to git hit!”

Henceforth the dozen constituted a bodyguard for “the women” and accompanied them everywhere. Yet several of these chivalrous protectors were taken away before the end of the summer to an adjoining county to be tried for participation in Kuklux raids, and still more were obliged to spend a good share of their time in the town jail, where there was often fierce fighting among the youthful prisoners.

III

“The women” soon found that the violence was only one side of the story, and by no means the darkest. In their

p. 320

trips through the country they found much neglect and suffering. Shut off from the rest of the world, amid its maze of mountain ranges and narrow, winding valleys, for more than a century, this primitive pioneer country, settled by men and women who, with rifle and frying-pan, followed in the footsteps of Boone and his companions, had never recovered from the ravages of the Civil War. Since then it had suffered still further from the ruthless exploitation of its natural resources by the outsider, so that the people, utterly impoverished and cut off from all contact with the currents of modern progress, had become socially and economically disorganized.

Owing in part to the rapid increase in numbers, but even more to the extinction of game and the exhaustion of the soil, the principal problem had become that of overcrowding. “The women,” curious to know where all the children who found their way to the settlement camp came from, explored the country thoroughly. They soon discovered that every creek at all capable of growing corn (the one staple product) had a population far in excess of its power to support, and that many of these people, with all their pride of race, traditions of sterling patriotism, and remnants of an older civilization and culture, were crowded into one and two-room cabins, sometimes without windows.*

Here and there, in odd volumes unearthed in humble homes, “the women” found evidence that some, at least, of

p. 321

the early settlers had been men of a certain education and even crude literary culture. but in the course of time, although vague traditions of scholarship remained in an occasional family, every trace of book learning was lost and few of the older people could either read or write. There was some improvement among the children in this respect. But in most of the country schools, they visited the teachers were incompetent and the teaching was listless and perfunctory.

The moral and religious training of the young was almost entirely neglected. The Preachers nearly all begged to the old regular Baptist church, primitive, sect, which recorded it as painful to pay its preachers to conducted Sunday-schools, or to support missionary societies yet Toler- manufacture and sale of moonshine,- among its own members and did little to improve the moral and social standards. the was little or no social life because parents of the better class objected to having their children attend the gathering rings which so often ended in drinking and shooting.

*One father actually threatened to shoot his children if they attended Sunday-School.

Narrow and dogmatic, interested only in “searching the mysteries of the Scriptures,” or in violent controversies over subtle points of doctrine, most of the preachers were as unlettered and superstitious as their humblest auditors, though often possessing shrewd with and native eloquence.

“The women” attended a “funeral meeting,”** held on the edge of a creek beneath the shade of a great beech, where the people stood about in groups or sat in rows on rude sapling benches. This was regarded as a great social event. The women came dressed in their best clothes. The men talked politics or swapped horses. The young people sauntered on the outskirts in couples or companies, while one boy went about through the crowd peddling the “moonshine” with which he had filled his saddle-pockets.

In front row, facing the preacher, sat the “bereaved widder” and his second wife, whom he had married just four months after the death of the first. They were both under one torn umbrella, which she held while she fanned him with his hat.

**There is a distinction between a “funeral” and a”burying” in the mountains. The former is more in the nature of a memorial service and may be held at any time after the death of the deceased.

p. 322

Somtimes he placed his elbows on his knees and held his head in his hands. Then he rested his head on her shoulder, while they both wept.

“My neighbors and my neighbors’ children,” the long-haired, patriarchal preachers one of the most popular in the country, began in trembling tones and uncertain accents, “we have met upon a funeral occasion. May our meetin’ be done in decency and good order, and now let us draw in the wanderin’ and scatterin’ parts of our minds. Let us be unstripped of self and carnality, people under the shadow of my voice.”

For fully an hour he offered consolation to the bereaved, discoursed on the mysteries of immortality and the resurrection and uttered dark warnings to his hearers on the consequences of their sinful courses. Once he stopped short, with an apology to remove his coat. Then he searched through all his pockets for a big black silk handkerchief to mop hi moist brow. Resuming, he promised to speak only a few minutes longer, but kept on for nearly another hour, losing himself in a flood of bizarre mystical metaphors:

“I believe religion can be tasted and felt,” he shouted. “When the golden bowl overflowed, it emptied into the golden candlestick through the golden pipe, and did not rust. May God dig about our hearts with the Maddock of his love and break up the fiery ground to take root downward and bring forth fruit upward.”

Then, suddenly, coming abruptly to an end, he exclaimed:

“I lied to you before when I said I aimed to quit; but now I aim to set down and let Brother Blank preach!”

IV

The sad disintegration of mountain society rendered all the more striking to “the women” the splendid personal qualities of the mountain people — their scrupulous honesty, their instinctive courtesy, their proud hospitality to strangers, and above all, their pathetic eagerness to “get education” for their children. Bad as Knott County was in those days, one could not say of it as of a certain notorious American municipality, that it was corrupt and contented.” These scions of a superb stock were victims of circumstances rather than of their own undisciplined passions, which were the result,

p. 323

not a cause, of their economic condition. They never, even at their worst moments, lost a sense of the destiny which had bee denied them, of the heritage which, here in what had once been the wilderness, their fathers had somehow forfeited. Elements of intellectual unrest, of moral idealism, were still latent among them, and had already begun to assert themselves — to seek, through a few exceptional men and women, some way out of the miserable impasse. And it was upon these that “the women” counted to aid them in their struggle to rescue this flotsam and jetsam of a submerged race.

It had formed no part of the original intention of Miss Stone and Miss Pettit to start a regular school in the mountains. A permanent home for settlement work and a certain amount of industrial education, especially among the women, whose harsh lot and narrow outlook won them the special sympathy of their own sex — this had been the height of their modest ambition. But they soon saw the necessity of establishing at some point an educational institution combining academic and industrial training with various forms of social service.

The second summer the citizens begged them to start such a school at Hindman. To their objection that they didn’t know how to teach, the men said:

“You’ll know how to get somebody who does!”

“But we have no money.”

“Go out and tell the world about our needs,” the citizens persisted. “Tell anything you want, but get us a school, and don’t start it anywhere but here.”

So they went out that winter and told the needs of the mountain people of Hindman. In April they returned with enough money to buy the old school building. With this was included about an acre of land. an old rough plank cottage adjoining was rented as a residence for the workers. The people themselves raised seven hundred dollars, and with this sum an additional three acres was added to the school property.

p. 324

That was just fifteen years ago. Today the equipment consists of one hundred and twenty-five acres, a schoolhouse, a power-house, a hospital, a central building containing laundry, kitchen, dining room, and girls’ dormitory, and a number of other buildings, including the biggest and best barn in the mountains, with a silo. Instead of the mere handful of house students with which the work started, there are now more than a hundred in the school “home,” and there is a staff of eighteen trained teachers and settlement workers.

The school* was a success from the very first. The news of the wonderful new opportunity that had come to the mountains spread like wildfire, and there was scarcely a corner in six counties it did not penetrate. Every rough mountain trail, every winding waterway, became a royal road to learning to these mountaineers, who had so long been b=deprived of their intellectual birthright. Whole families moved into Hindman from the remote back country, so that their children could attend the day-school, and one man actually traded his farm for a wagon and a pair of mules in order to make the move!”

Barefoot boys and girls of all ages came walking in from miles around begging to be allowed to work their way. A few were taken on this basis, but innumerable applications had to be refused, and ever since the school has had a waiting-list as long as that of a fashionable boarding-school in New England!

V

Let it not be thought, however, that all this was achieved without great effort and even without great opposition. Mr. John Fox, Jr., who described the school (though he does not give its name) in his fine novel, “The Heart of the Hills,” calls his heroine of humanitarian romance, “Saint Hilda,” after the Saxon nun who led her band to the wild Yorkshire coast. For, as he says, “she had gone back to the physical life of the pioneers, she had encountered the customs and sentiments of medieval days, and no abbess of those days, carrying light into dark places,

p. 325

needed more courage and devotion to meet the hardships, sacrifice, and prejudice that she had overcome.”

It is difficult to give any adequate idea of what it means to start a school in a primitive and undeveloped country which is still in the pioneer stage of civilization, and where everything needed has either to be created on the spot or else brought in from the outside at incredible labor and expense.* As the crowds of children from the back country clamored for admittance new buildings had to be erected as rapidly as possible. Day after day through the dead of winter the workers walked and rode up and down the deep ravines and over the heavily wooded mountains, to select and measure the

*The fifty mile trip from Jackson to Hindman took five days for a load of freight weighing fifteen hundred pounds, at the rate of one dollar a hundred.

p. 326

trees which must be cut before the sap began to rise, toward the end of January. While the men felled them and pitted the logs, “the women” themselves went back and forth, leading a team of mules, driving a yoke of oxen, or carrying a crosscut saw, broad axe, or cant-hook on horseback from one force of workmen to another, because if they did not do these things some man must stop his work, and that would mean delay.

Then when the logs had been hauled down from the hillsides and piled high in the school yard, a sawmill was brought in and the work of construction began. It went forward with a rush, Steam was got up every morning before dawn and the sawing began by daylight, Over fifty men and boys often worked until long after dark. So the logs went rapidly from saw to planer, from planer to wall. Sometimes, when the material was assembled, they had an old-fashioned “log-raising,” when the fathers came to help the boys “lift the house” and the mothers cooked the dinner for all hands in great iron kettles hung out under the trees.

The skill shown by “the women” in the construction of these buildings gradually overcame much of the prejudice that had persisted against the school from its foundation, among the more ignorant and narrow-minded mountaineers, because it was a “woman’s school,” and against its founders because they were “fotch-on” women and “furriners.” For, as one man who had frequently asserted that “no woman is fit to teach school, anyway,” now declared:

“If them women kin teach school as good as they kin build log houses, they’re sure all right!”

But, above all, it was the disasters that from time to time threatened the settlement with the total destruction that succeeded in winning the entire confidence and support of the community. Twice, when practically the entire settlement has been wiped out by fire, the citizens have rallied wonderfully to its aid, furnishing food and clothing out of their own scant stores for the workers and taking these into their own crowded homes. The second time, in particular, showed the hold “the women” had gained upon the heart of the “highlanders.” It was feared that the former would now discontinue their school or transfer it to another locality in a number of other counties having offered special inducements. So a mass-meeting was called in the court-house on two

p. 327

hours’ notice, and in a few minutes those who, eight years before, had been able to contribute only seven hundred dollars to start the school, now raised six thousand dollars in cash and labor for the work of rebuilding.

Nor was this all. As soon as the meeting was adjourned, riders were despatched [sic] throughout the country to collect money from those who had not been able to attend, If they proved at all recalcitrant, they were reminded in forcible terms of the benefits they had received, directly or indirectly, from the coming of “the women,” and were thus shamed into making a liberal contribution. At the same time, a committee met to assess former citizens who had left the country. Drafts on these were actually drawn up, signed with their names, and presented at the local bank, which honored them without a question. And it is said that not one refused to recognize the obligation thus involuntarily incurred.

VI

“Ten years ago, when I met you women,” a mountain preacher wrote to Miss Pettit in 1912, “and you told me you had decided to have a school in Hindman, I thought to myself: ‘A failure. What can those women do with eight stills in a circle of five miles of Hindman?’ In five years you could not get whiskey in Hindman or anything, and no violence was used. People saw something better and took advantage of it.”

Certainly, no people ever responded more promptly to an opportunity thus offered them. Recently the Circuit Court judge, in his charge to the grand jury, said that while Knott County was formerly one of the most lawless in the State, it now sent fewer to the penitentiary than any other, and had not had a homicide in eight years. This remarkable change he attributed almost entirely to the influence of the school.

It has indeed accomplished much toward the moral and social betterment of the community it has discouraged criminal disorder by fostering a better tone of public opinion. it has dealt a heavy blow to the liquor interests, chief fomenters of trouble in the Cumberlands. It has greatly diminished illiteracy, as well as increased the demand for higher education so that Knott County –one of the poorest financially and in other ways — to-day sends more students to college and university than any other in proportion to wealth and population. It has cultivated a new sense of responsibility in its professional men, a new sentiment of solidarity and co-operation in its citizens. It has waged a relentless war against unsanitary and disease-breeding conditions, so that if recently a determined effort has been begun by the Federal authorities to eradicate the terrible malady of trachoma from the mountains, this is largely due to the intelligent initiatives of “the women” in drawing the attention of the outside world to the grave situation they discovered there.

Above all, it has done these things with sympathy and understanding and without sacrificing whatever was already of vital value in the spiritual life of the people. Thus it has kept alive among its students, by means of a school society, a love of the old ballad literature which has been preserved in the mountains more than a hundred years by pure oral tradition, so that nothing is more common today than to hear the girls going about their work in kitchen or laundry singing “Barbara Allen” or “Pretty Polly.”

As for the women, whom Miss Stone and Miss Pettit had most of all hoped to help by coming into the mountains, their

p. 328

lot has been sensibly alleviated. New interests have been created, new opportunities opened for them, especially through the renewal of such “fireside industries’ as basketry and weaving, which were beginning to disappear owing to the introduction of cheap manufactured articles from without. The school now finds a market outside the mountains for the product of these women’s inherited skill, and it has in the last few years sold for their account thousands of dollars worth of blankets, coverlets, linsey-woolsey and other homespun fabrics, and baskets.

The education of the girls as housekeepers is already beginning to have its marked effect upon the general standard of living. It does not take long for a traveller in the mountains nowadays to tell when he has had the good fortune to find a Hindman housewife in the home where he happens to spend the night.Nor is it the outsider alone that is thus appreciative. The mountain men themselves are acutely aware of the difference in their own comfort and well-being, and when some of the older girls have to stop school in the spring to help put in the corn, their fathers sometimes come to say that they will spare them from the fields long enough to attend the cooking-classes. Also, when a boy has been either to Hindman or Berea, he is likely to include, in his plans for the future, marriage to “one of them domestic-science” gris.

The very appearance of the town and of the surrounding country reflects the deep-seated changes that have been wrought there. Better homes have been built, better stores have been opened, and the roads in Knott County to-day are superior to those in any adjoining county. “The women” who, when they first came to the mountains, brought in panes of window-glass and sold them at cost to the people in the back country, also introduced the electric light, so that Hindman enjoyed this advantage long before many a mountain town now on the railroad.

VII

In spite of all that has already been done, an immense amount of work still remains to do. Indeed, so far but a mere beginning has been made in these mountains, where life, held so long under a strange spell of slumber, is now rapidly awakening.

“This whole country is a-lookin’ to you women to educate the children some way!”

This is the greeting “the women” receive as they ride “hither and yon” through the mountains seeking new opportunities for human helpfulness. And no one who does not know the toil necessary to the mere maintenance of life in the Cumberlands, or the melancholy that lives deep in the hearts of the hill people, can possibly appreciate the pathos contained in this salutation or what the school itself means to the county.

Yet every week brings to the workers testimony as to the value placed upon it by the people themselves. Scarcely a day passes without some appeal. Perhaps it comes in a letter — occasionally four or five will arrive in as many days from one persistent boy. Perhaps a mother walks thirty miles in the winter through the deep mud, with “two gals that have sot under a shade tree an’ larned the best they could by theirselves.” Perhaps it is a father who has “brung all his young uns fifty miles for to see and larn.” Or perhaps a grown boy, like Mr. Fox’s hero, Jason Hawn, rides in from the farthest corner of Breathitt or Letcher or Leslie County, hitches his horse to a “flying limb,’ announces simply, as he did, “I’ve come over hyeh to stay with ye,” and when he is told there is no place for him — for no matter how much they may build there is never room for all — says: “Shucks! I can sleep out thar in that woodshed. I hain’t axin’ no favors. I got a leetle money, an I can work like a man.”

The school has hundreds of such boys and girls waiting for places in it to-day. The hardest thing for “the Women of Troublesome” is the necessity for turning away so many eager applicants. Yet surely there could be no greater inspiration for them in their self-appointed task than the touching faith of the mountain people in the school as the one hope of the country for its children!

Return to GUIDE TO SCRAPBOOK BEFORE 1929

SEE ALSO

RELIGION A Mountain Funeralizing

CELIA CATHCART “A Funeralizing On Robber’s Creek”

DEAR FRIENDS LETTER 1911 (HINDMAN)

EVELYN K. WELLS Horseback to Hindman

LUCY FURMAN

KATHERINE PETTIT Director