Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 16: Special Events

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH:

STIR-OFF – SORGHUM MOLASSES

The following account details a “Stir-off” in 1944 at the home of “Uncle” Henry Creech, son of William and Sally Creech who lived approximately a mile northeast of the settlement school. “Uncle” was a common form of both respect and affection. Henry Creech, son of William Creech gave his land that Pine Mountain might begin its work educating families in the Pine Mountain valley in Harlan County, Kentucky. But, Pine Mountain soon learned that education was born a twin and that they had much to learn from the community. The Creech home was a favorite gathering place for many who worked at the School and a rich learning environment for those interested in mountain ways and customs. Uncle Henry was a man of many talents and one of those was his understanding of what makes a good batch of sorghum and more importantly, what makes a good neighbor.

A “stir-off” was a common community event in the early years of the School and one eagerly looked forward to by the children. The warm, sweet sorghum, dipped out on long canes cut from the sugar cane stalk was enough to satisfy even the most discerning “sweet-tooth”.

[From 1944 NOTES]

STIR-OFF AT UNCLE HENRY’S

Children’s Stiroff at Uncle Henry’s House – Mable and Ralph Cornett, Helen and Steve Hayes, David Barry, Mr. Creech, Kathy Barry, Elizabeth Dodd. September, 1946. nace_1_047a.jpg

GALLEY

- Sorghum Stir-off – Henry Creech, Harrison Cornett. [nace_1_047b.jpg]

- Children’s Stir-off, September, 1946. Mable and Ralph Cornett, Helen and Steve Hayes, David Barry, Mr. Creech, Kathy Barry, Elizabeth Dodd. [nace_1_047a.jpg]

- The school attends a stir-off [Sorghum/Molasses] at Henry Creech’s, 1946. [nace_1_046c.jpg]

DESCRIPTION OF A STIR-OFF AT UNCLE HENRY’S HOUSE ON ISAAC’S CREEK from 1944 NOTES

“You who have been using the 1944 Pine Mountain calendar have during October looked many times at the picture of a “stir off” at Henry Creech’; place. When sorghum is plentiful, and the weather is right it is Henry’s good custom to invite the whole school for an evening “stirring off”. Early in September we began asking each other when the cane would be ready, and presently on the heels of our wondering. came the invitation. All of us knew that that day since dawn, cane cutting had been going along down on Isaac’s Creek, and all being well, we would “stir off” about eight o’clock.

We tramped up the creek as dusky dark changed to night, and our torches were stars strewn all down the road, from the speedy vanguard to trailers clambering over the stile above Big Log House, a shouting, singing crowd. We rounded the last bend to see the

fire glowing in a gulley below, close to the creek, and Henry Creech’s dark figure weaving shadows with the swinging lantern. Early arrivals clustered about the fire, whittling ends of cane for us to dip the foam with. While we waited for the foam to be ready the group settled here and there to sing -ballads or run sets on the grass. The steady hand-clapping of the dancers and the shrill calls of the leader accompanied strains of “Sourwood Mountain” and ‘The Ground Hog”.

As usual there were newcomers to the mountains who had never heard of a stir off and we asked Henry if he would tell the new ones all about the process.

“You have to cut the cane and then strip the stalks and seems like one or two men working on the job can do more than all the women you could set to it in a day. I don’t know why, but it’s that way. You have to put the stalks in the cane mill, and then hitch up the horse, so he pulls it around and around, and then the cane juice drips down the spout in the tub and you pour it in the trough here.”

He paused to adjust the lantern, and we looked at the trough, which was like a wide flat boat, divided into two sections, and about three quarters full of dark liquid, now beginning to foam on the top. It was not yet ready because the foam was still green, although some of us were licking green foam to Henry’s mild disapproval. He said it “would cause stomach complaints” before it was ripe.

‘Then you cook it, and it has to cook for about eight hours, ’till it boils up and foams over the top, and when the foam comes on you skim that off and throw it away—and finally it’s a nice yellow foam, and that’s when it’s good for licking—and then you decide when it’s done and pour off the molasses in a lard can, and that’s all.’

It was not all really, for by the end of the explanation the foam was ready for dipping. This, we should explain. is done with paddles, which are cane stalks with flattened ends, used like spoons. (To be sure it takes time for the uninitiated to get used to the idea that everybody can hygienically dip into a common trough of boiling sorghum.) 120 paddles dipped, 120 eager tongues tasted and licked. Before sorghum melted in the trough before our eyes.

But we tasted more than sorghum. We tasted the joy of a real country function. Here in the mountains our social occasions are made of simple homely happenings…

… The stir-off ended. But the “sweetenin” we eat some dreary day next February will bring back the wood-smoke and firelight.”

[Recounted by Robert Creech, son of Mr. and Mrs. Henry Creech, grandson Of Uncle William. Killed in action in the South Pacific area on Sept. 27th, 1943 [?]. Written by Alice Cobb [?] From: NOTES – 1944]

DESCRIPTION OF A STIR-OFF and SET-RUNNING AT UNCLE SOL DAY’S

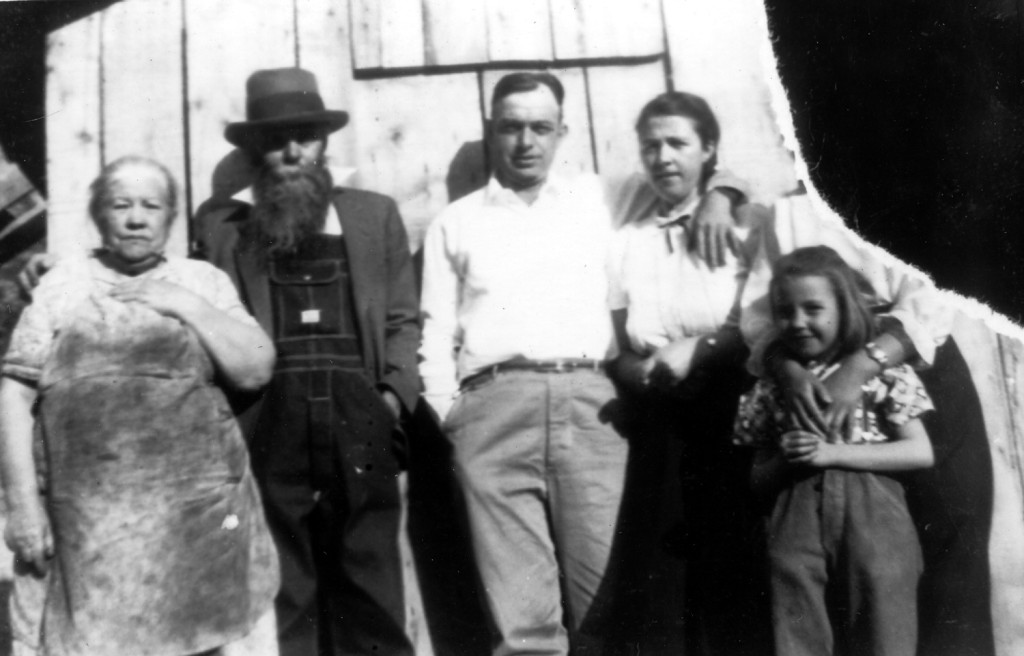

Friends & Neighbors – VI-51 – 1717. “Black” Sol Day and family.

Sol Day‘s stir-off. Behind the house, they had set up a great trough on stones, under which they kept a long line of fire. Three or four men with lanterns (this was an evening affair) were keeping the sorghum from burning, by stirring it with paddles and the sweet smell just filled the air. All around were neighbors with sticks of sugar-cane, which they dipped in the foam on top and then sucked — good, but awfully sweet! The moon came up and lighted the sugar patch on the hilltop where all the sweetness came from. Finally, they drew the trough off the fire and poured the liquid off into buckets, and then we all went down to the sawdust pile and watched the set-running. A set is really a quadrille, only danced as fast as you can do it, the boys snapping their fingers to speed things up and calling out the figures, “Wild Goose Chase, “Home Swing”, etc.

[From Evelyn K. Wells’ Transcription 1915 of her letters home.]

![Angela Melville Album II - Part III. "E.K.W." [with dulcimer]. [melv_II_album_313.jpg]](https://pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/melv_II_album_313-194x300.jpg)