Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series: DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH

Foodways

FOOD CHALLENGE AND WWI “THE GOSPEL OF THE CLEAN PLATE”

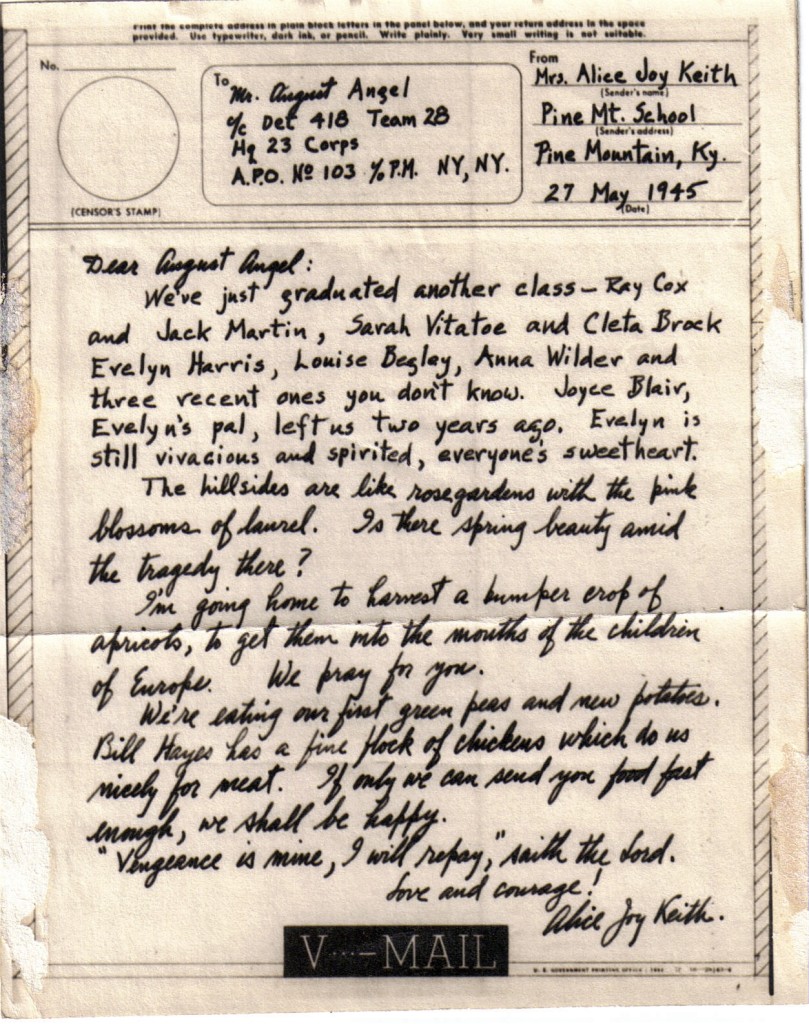

By 1916 it was clear that Pine Mountain Settlement School was food challenged and more ways were needed to supply the workers and children with a sustainable and nutritious diet that would go beyond the current mountain practices. By 1917 the challenges and food shortages of WWI were being felt across the country and Pine Mountain joined thousands of institutions in subscribing to President Woodrow Wilson’s programs to conserve food. Administered by Herbert Hoover, the “Gospel of the Clean Plate,” was started as an attempt to ensure that there would be adequate food for the troops and for the Europeans caught up in WWI. The government designed a program for certain days to be “meatless, sweetless, wheatless and porkless.” Each state was charged to oversee the program and to monitor commercial businesses and restaurants.

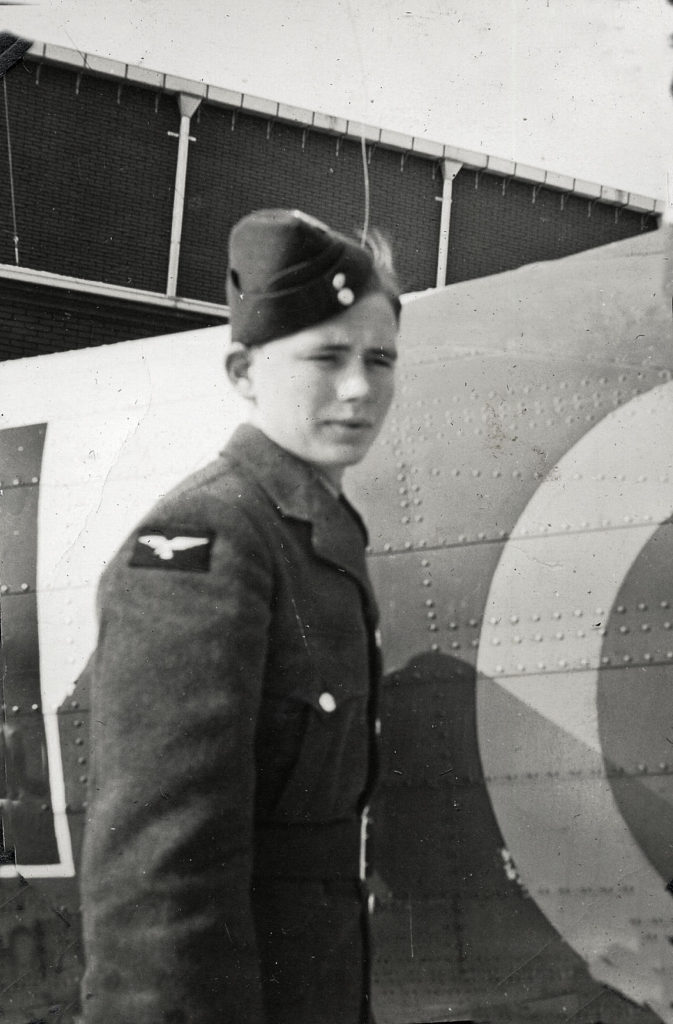

The staff at Pine Mountain followed the war efforts intently, as did many Americans. Many of the staff came from missionary families, and were familiar with many of the dynamics of the European conflicts. One staff, in particular, was following the war daily. Leon Deschamps, a Belgian, still had family in Belgium and watched the war unfold with great anxiety. In May of 1917, the strain was too much and he left the School to fight in the Great War for his homeland. Deschamps was much admired by the staff and students at the school. He was a vital part of the farming activity at the school and when he left his departure left a void and not just a little anxiety. Before he left, Deschamps made sure that Pine Mountain understood that he would return following the end of conflict. He also made sure that the School was committed to the support of the Belgian Relief Fund. Deschamps, as the school’s forester and farmer knew what the loss of a farmer at Pine Mountain meant, but his need to join the war effort was overwhelming and immediate, Mr. Baugh, who had worked with him, assumed his responsibilities in the forest and the farm and the campus had Deschamps promise to retrun to Pine Mountain following the end of the conflict. His strong belief in the war effort and his subsequent departure stirred many students to action to support the War and was their first introduction to a world “beyond the seas.”

The children began to imagine Mr. Deschamps in the fields of war and for them, Belgium became a real place. A campaign was put into place by the students, not just the staff. They determined to save money for the War effort, and particularly for Belgium, by rationing themselves once a week. This rationing included adhering to the “Clean Plate Club”. The children took the idea one step further.

On a chosen day, the children planned to forego their meal and to substitute a lean fare of rice with cocoa rather than a full course meal. These rice and cocoa meals were adopted following WWI for other occasions when the Schoolchildren adopted some cause which required saving money. For example, the swimming pool was a rice and cocoa student project but clearly, other campaigns held little persuasion alongside the looming disaster in Europe and the danger to one of their own — the forester and farmer, Leon Deschamps.

“JUST THE WAY I LIKE IT!”

The students at Pine Mountain were well prepared to be “Clean Plate” eaters as one of the rules of the School was that all students must eat at least three bites of the food served to them. The story is told of a young boy who was served some soup from the communal large bowl at the center of the dining table. As he lifted the spoon to his mouth and took the first taste he quickly offered his uncensored opinion. “It tastes like soap!” he exclaimed. Somewhere in the depths of the kitchen a soap bar had inadvertently fallen into the soup pot. The young boy, startled all the children as no one was to comment on their like and dislike of any one food. He looked around the table at his fellow diners and quickly recovered, “And, that’s just the way I like it!” he said as he looked sharply at the supervising staff at the table and continued to slurp the offensive soup.

The Clean Plate Club asked that America, ” Leave a clean dinner plate. Take only such food as you will eat. Thousands are starving in Europe.”

PRACTICE HOUSE/MODEL HOME/COUNTRY COTTAGE

Another piece of the effort to promote the “Gospel of the Clean Plate” was the industrial training that young women received at Practice House, the home economics training center at the School. Practice House, also called Model Home and Country Cottage was built with funds that were donated to the School by the New York Auxilliary of the Southern Industrial Educational Association. The donation was a testimony to their very active woman NYC President, Mrs. Algernon S. Sullivan. Mrs. Sullivan was a generous supporter of Pine Mountain Settlement School. The Algernon Sydney Sullivan Award is well known in academic circles for its high minded ideals. For example : the Algernon Sydney Sullivan Award is presented to undergraduate seniors at colleges on vote of the faculty for an individual who “exhibits Sullivan’s ideals of heart, mind, and conduct as evidenced by a spirit of love for and helpfulness to others, who ‘excels in high ideals of living, in fine spiritual qualities, and in generous and unselfish service to others.’ ” [Wikipedia]

Practice House/Country Cottage was just that, a place to practice frugality and attention to good housekeeping, gardening, cooking, budgeting, and other household skills. These were the skills that made the difference during war-time.

Evelyn Wells in her gathered letters and history of the School describes the Practice House in this manner:

“Our Country Cottage aimed to show them [the girls at Pine Mountain] what was good about their own methods, and to introduce to them others that they badly needed to learn. Some ideas with which we started had to be abandoned, such as well with water running by gravity to the kitchen sink because we could not strike water …”

Cornelia Walker, a Cornell graduate, and our Domestic Science teacher in 1922-1923, was the first hostess. There followed Mrs. Seidlinger, Mary Work, Annette Van Bezey, and in 1926, Marguerite Emerson. During Mrs. Emerson’s regime, the name was changed from the Model Home to the Country Cottage.

No attempt is here made to estimate what this building has meant to the groups of girls who three at a time have spent six weeks in the Country Cottage, cooking, living on a carefully worked out budget, caring for the cow and selling its milk, and entertaining, under the guidance of the housemother. The garden was also important, and a summer worker has usually (and with varying degrees of success) canned its produce for the family’s winter consumption.

Two lots of lumber were measured out “according to the Country Cottage plan” and were then sold to community families. The house and the terraced gardens were copied by many in the area.

The structure was built between 1922 and 1923 and was then remodeled in 1927 and again in 1951. It became a staff residence in 1940 and today serves as a residence for various interns at the School.

Evelyn Wells noted that “We regret that as a neighborhood house it has not become the center that was one of its ideals at the first.”

While the home only accommodated three girls at a time, the impact on those three girls was profound and had a lasting effect on the surrounding community. [The girls were rotated through the program for short periods of time.]

[From The Pine Cone, May 1935, p.3]

“Groups of four or five girls have lived at Practice House each six weeks period of this school year to learn what they could of home life. Twenty-eight girls have had the privilege of making it their home this year while at school.

We realize just as a nation is the composite of the states of which it is made, a state is dependent upon the atmosphere of the communities with it and in turn, the atmosphere of a community is the home life in the community. We feel we can do a little bit of world service by helping to make the girls of Pine Mountain worthy home members. A worthy home member is one who not only does her share of the work willingly but one who adds to the joy of the home by her desire to do the right thing and by her pleasant courteous manner.

Some of the more immediate aims which we have held before us have been as follows:

1. The desire and ability to prepare attractive, tasty meals that were well balanced and inexpensive.

2. The desire and ability to plan and carry on the work in an orderly way.

3. To develop a feeling of helpfulness, thoughtfulness and interest in others.

4. Desire to become a socially poised person.

The work has been grouped and each girl has taken her turn at the various types of work to be done in the home life here

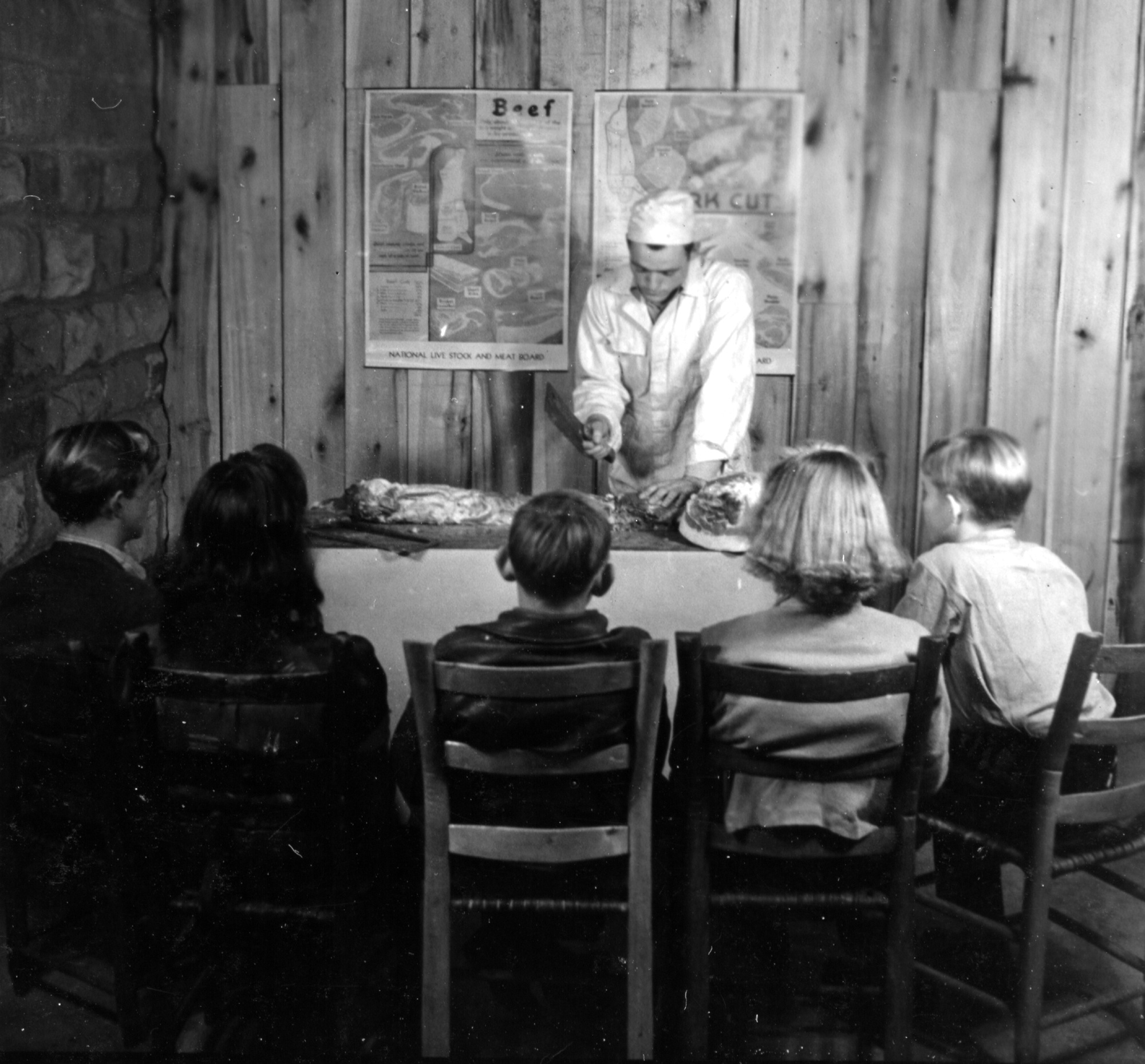

BUTCHERING

“Mr. Hayes has been teaching his A-1 and A-2 Agriculture classes how to butcher hogs. Hence good pork chops and hams appear on the dining table.”

Most all butchering of meats was conducted by the school during the Boarding School years and meats were canned, salt-cured, sometimes frozen, smoked, and sometimes dried.

This recipe for liver-loaf is most likely scaled for calf liver, but pork liver and even chicken livers could be substituted. The author would have no desire for any!

[From The Pine Cone, April 1934, p.3]

LIVER LOAF – REALLY!?

Liver Loaf

One way to make a popular cut of the animal go ’round!

1 1/2 lbs. liver

1 1/2 cup dry bread crumbs

1-4 cup melted fat

1 egg

1 teaspoon salt

1-8 teaspoon pepper

1 onion — chopped

Pour boiling water over liver. Let stand five minutes. Drain and chop fine and add all other ingredients, mix thoroughly and shape into loaf. Put into greased baking dish, or lay strips of salt pork or bacon on top, add one cup water, bake one hour, add one cup tomatoes or tomato soup fifteen minutes before taking from the oven.

IN THE KITCHEN

Kitchens in the community varied widely. Delia Creech, wife of Henry Creech , son of William and Sally Creech, was known for her frugality and the rich maple sugar she created from the Creech “Sugar Camp”.

In the photograph below a woman prepares food in a traditional enameled metal bowl. Sometimes called flow-ware, these enameled metal-ware pots were favorites in Appalachia and in the South at the turn of the century. Either a blue or a red flow-ware color these metal-ware containers were found in many homes and continue to be prized as family keep-sakes.

On this page below, is Aunt Sal (Sally Creech) seated at her churn in her very tidy kitchen. In this posed photograph of Sal, she is seated at the churn which was a necessary kitchen tool for all households that owned milk cows. Tools in most mountain households were often hand-made or were purchased from “Tinkers” who roamed the mountain valley with wares such as tin pans, crockery, and wash-boards. “Tinkers also made it part of their trade to repair items. Rarely would any item be thrown away and then only if completely broken or ruined.

Kitchens could also be as rudimentary as cast-iron pots on tripods located near the backyard doorway, or they could be fully equipped centers of family life., as seen in this photograph. The dangers associated with yard kitchens, the soap pots, and the “blue” pots (indigo dye pots), often located in the yard, are obvious. Small children and adults frequently suffered scalds and burns from these open-air kitchens. A daughter of Aunt Sal was scalded and died from the burns. The luxury of an indoor kitchen was only for those whose home was large enough to accommodate an indoor cooking space. More frequently, the fireplace was a center of household meals and large cast iron pots hanging on hooks or settled on stones, or buried in cinders, were sources of family meals. This kind of cooking encouraged stews, soups, and simple baked goods.

HOME ECONOMICS RECIPES

A variation of the old and well-known favorite:

Spider Corn Bread

1 3/4 cups of milk

1 egg

1 cup corn meal

1-3 cup of flour

2 tablespoons sugar

1 teaspoon salt

2 teaspoons baking powder

1 tablespoon fat

Beat egg and add one cup milk; stir in corn meal, flour, sugar, salt and baking powder which have been sifted together; turn into a heavy, new frying pan in which the fat has been melted; pour in remainder of milk but do not stir it. Bake about twenty-five minutes in a hot oven. There should be a line of creamy custard through the bread. Cut like pie and serve hot.

Don’t let an aversion to spiders or bugs stop a trial of this corn-meal bread. It is delicious!

One of the goals in later years was to provide at least a quart of milk per person per day. Further, the staff was allotted quarts through the end of the Boarding School years (1949) This supplement, no doubt, was a great off-set for the prior Great Depression years as well as both World Wars.

Meals at Pine Mountain cost the school 33 cents per person per day in 1925 and “it requires great skill and ingenuity to serve interesting food for this sum of money, in a place where there is no ice, and no market where the fresh meat is local beef or pork possible only in cold weather. Miss Gains, [Ruth B. Gaines] who has been with us thirteen years, has developed so unusual an ability in dealing with these circumscribed conditions that she has often been urged to get up an institutional cookbook for others up against such difficulties as we have .”

RUTH GAINS MENUS

Miss Ruth Gaines menus for yesterday and today:

BREAKFAST

1. oatmeal, stewed prunes biscuits with butter substitute

2. Cream of wheat, cocoa, biscuits with butter substitute

DINNER

1. Chicken and rice loaf, creamed turnips, chopped cabbage and celery, soup beans, cornbread, chocolate pudding

2. Creamed tuna fist, sweet potatoes, green beans, cold slaw, cornbread, jello

SUPPER

1. Rice and milk, cornbread, canned pineapple

2. Potato salad, cornbread, one-egg cake

Our main dishes for dinner are wonderful mixtures of fish and potato, rice and tomato, cheese and bacon. Variety at breakfast comes with fish-cakes, potato cakes, French cream toast, and at supper with a vegetable or cream soup, a bean or potato salad. “

[Worker letter, n.d., source unknown]

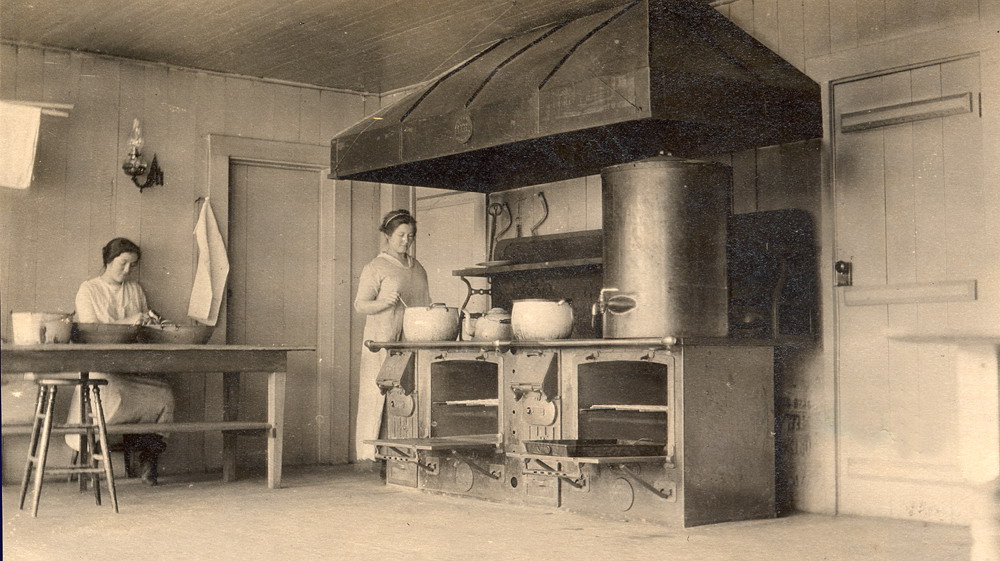

OLD LAUREL HOUSE

Kitchen in Old Laurel House

The earliest kitchen at the school was very rudimentary until a new kitchen was planned and included in the first central dining and community building called ‘Laurel House.’ For the day, it was a state of the art facility and was equipped to accommodate the growing population of the school. The fire that destroyed this first Laurel House in 1943 was a tragedy in many ways. It seriously disrupted the food supply at the school and the loss of life in the tragic fire was emotionally devastating for many who worked and knew the students who died in the fire. While it may be suspected that the fire began in the kitchen, it is known that was not the case and that the small living quarters in the building was the source of the fire.

GIRL’S HOME ECONOMIC CLASS 1934

The Girl’s Home Economic Class of the tenth grade, under the guidance of Miss Smith has been making Menus for the day and testing them by the following rules:

1. Distribute the protein, carbohydrates and fats equally throughout the day

2. Do not serve the same food twice in one day.

3. Do not serve more than one strongly flavored food at a meal.

4. Balance the soft, solid and crisp foods.

5. Do not serve several acids or sweet foods at one meal.

6. Season foods mildly, but tastily.

7. Serve left-overs in a new form and always attractively.

8. Greasy meats and vegetables and poorly seasoned foods are not appetizing.

9…Include daily —

(a) One quart of milk for each child and one pint for adult.

(b) Two vegetables besides potatoes. (one raw)

(c) Two Fruits. (one raw)

(d) Whole ceral in some form.

(f) One egg and a serving of meat for an adult.

10. Serve light desserts, as fruit or milk pudding with heavy meals.

11. Serve heavy desserts, such as, pie or cake with light meals.

12. Serve only one relish or jam at a meal.

13. Avoid serving colorless meals.

14. Plan simple meals.

15. Consider the cost carefully.

MINTED CARROTS

2 cups grated raw or cooked carrots

1 cup water

4 tablespoonfuls sugar

4 tablespoonfuls chopped mint leaves

4 tablespoonfuls butter

Cook the water and sugar until syrup like. Stir in the butter and add the mint leaves. Pour over the carrots and serve.

The family will not object to carrots when served in this interesting way.

The Pine Cone,

February 1934

STOVES

When coal stoves with ovens became more common-place and could be afforded, baking was a point of pride for most mountain households . The regulation of heat in the coal oven was an art but once mastered the cook would rarely trade up for the newer ovens. Electric ovens became a part of some households when the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) brought electricity to the Pine Mountain valley. Through the Rural Electric Cooperative (REC), often referred to as the REA, or Rural Electric Association, a part of the New Deal programs of the late 1930s, many household routines changed, but life in the kitchen was very slow to change. While the electric stove became a regular household item following WWII it was slow to be adopted in the Appalachians. Propane gas stoves were used by some mountain families, but by far the most frequent home stove found in mountain communities until well into the 1950’s, was the coal stove.

Pine Mountain was fortunate to have a superbly equipped kitchen in the Old Laurel House and there the coal stove was a central source of fresh baked breads. The kitchen was staffed with a dietitian who was an important member of both the dietary health of the school and the homemaker educational programs during the Boarding School years.

The Pine Cone, Dec. 1934

MAPLE SUGAR MAKING IN THE KENTUCKY MOUNTAINS

“The time for making Maple sugar is during the months of February and March. The sap “startups” at this time. The trees are “tapped” and the sap is collected in a pail. Tapping is accomplished by boring a hole in the tree, driving a spout in and hanging a bucket on it. The sap looks like clear water but has a sweet taste.

Somewhere in the maple grove, there is a small shed, a “sugar camp” as it is called, to shelter the furnace, a large supply of wood and the evaporating pan.

When the sap buckets are full they are either carried to the camp by hand or the sap is sent through gutters. It is “boiled down” to a thin syrup and then it is taken out and boilded down to sugar in small pans.

It takes 50 gallons of sap to make one gallon of syrup ready for table use and a gallon of syrup will make about two pounds of sugar. “

[The Pine Cone, date????]

MOLASSES STIR-OFFS

Making molasses was another labor-intensive activity at Pine Mountain. The Creech family, near the school, almost always raised sugar cane, the source of the liquid used to create molasses.

First, the cane was harvested while still green but mature. Then, the cane was trimmed of leaves and bundles of canes were placed in a mill where the canes were crushed to extract the juice of the plant. The juice was funneled into containers and then deposited into a large iron pot or a flat metal pan that was positioned over a continuous fire. The pot or pan of cane juice was allowed to boil until it became sugar sweet, concentrated and thick. The foam on the top of the syrup was constantly dipped off the boiling molasses. Most often this was everyone’s job and a most rewarding of jobs. The foam sticks to the canes dipped into the molasses and make a sweet treat for all who come to “Stir-Off” the sorghum.

The young molasses is called “Sorghum.” It is sweet, light, and gentle in flavor. When the molasses is cooked more, the syrup became more concentrated and heavier in flavor and sugar. This dark molasses is the bulk of the molasses-making process. This very dark molasses, usually at the bottom of the pot, is referred to as “black-strap molasses” and the strong flavor of this residue was sometimes added to corn silage for the livestock. It to sweetened it and encouraged the fermentation of the chopped silage which was generally made from green corn stalks. The Gospel of the Clean Plate was not just for those seated at a table, it carried over into every aspect of growing, preparing, and making more palatable nature’s bounty.

“JUST THE WAY I LIKE IT”

hw/2019-06-10