Pine Mountain Settlement School

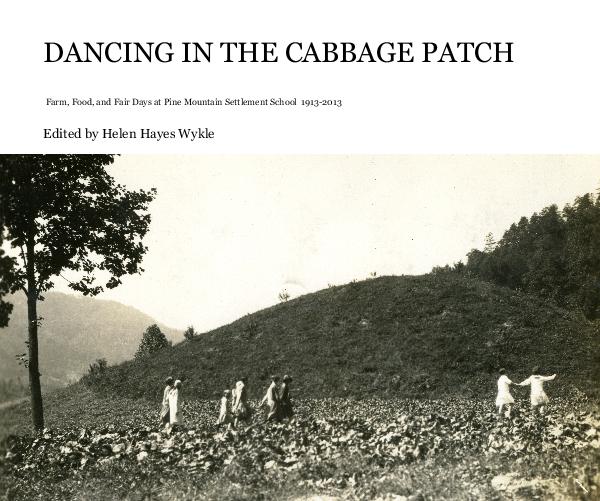

Series: Dancing in the Cabbage Patch

Helen Hayes Wykle

DIS-EASE

TAGS: disease, rural health, WWI, Harlan County, Kentucky, hospitals, health, pandemics, Spanish Flu, mining camps, COVID 19, coronavirus, typhoid, diphtheria, tuberculosis, scarlet fever, flu, measles, spinal meningitis, Harry Garfield, Frank J. Hays, UMW, United Mine Workers of America, Federal Fuel Administration Office

GETTING SICK IN THE MOUNTAINS OF EARLY EASTERN KENTUCKY

The Pine Mountain Valley is isolated. There is little to dispute this fact. It was extremely remote in 1913, the year the School came into being. Today, there are roads but the multiple circuitous routes and the distance from towns and a hospital (the nearest is in the town of Harlan 45 minutes away) continue to be dauntung and isolating.

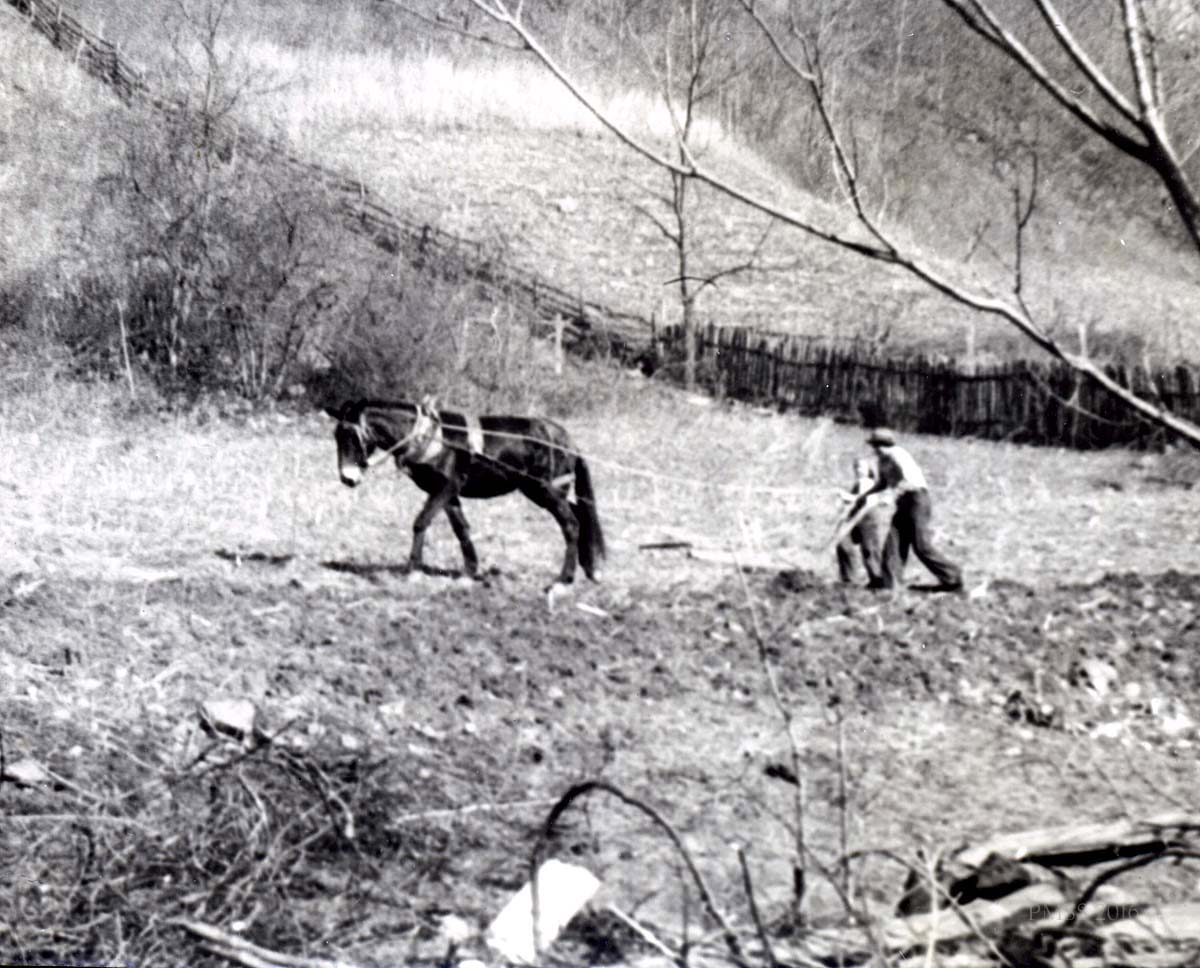

The health of people who live in the valley and in the hollows that branch off from the deep Pine Mountain valley is, like so many rural areas of this nation, daily put at risk from limited access to health services. Formed by the steep north-slope ridge of the long Pine Mountain that sits atop the Cumberland Plateau, the valley is faced by a south slope that joins a sea of low mountains, mostly sparsely inhabited. In the Central Appalachians, a mountain is both a barrier and shelter, yet, almost everyone who has visited this geography agrees that the undulating landscape of mountains, valleys and hollows is beautiful, peaceful —- but not easily accessed. This forced isolation in paradise is both a curse and a blessing.

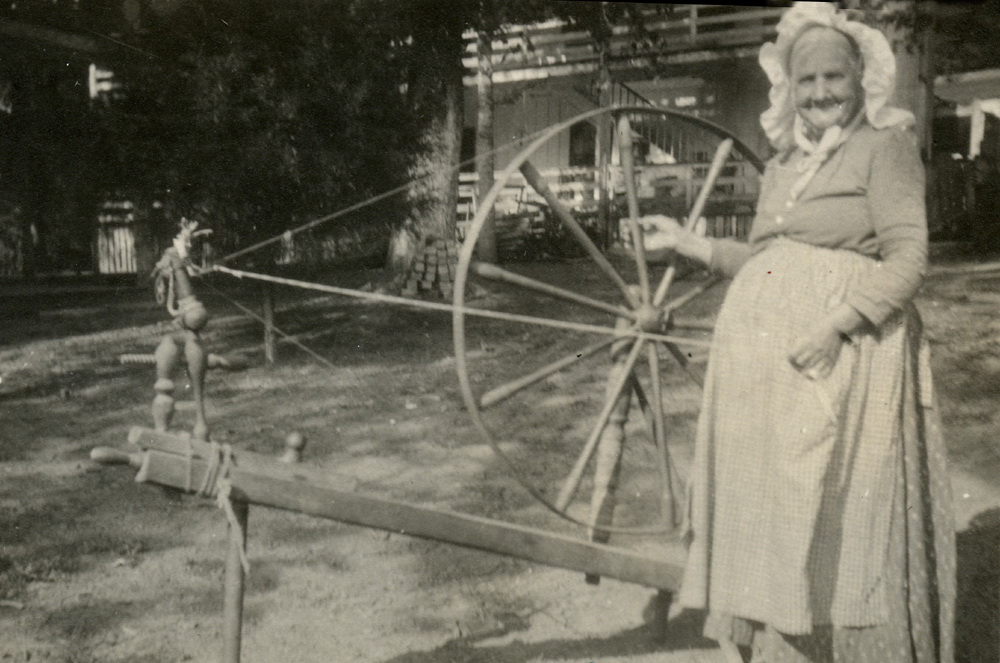

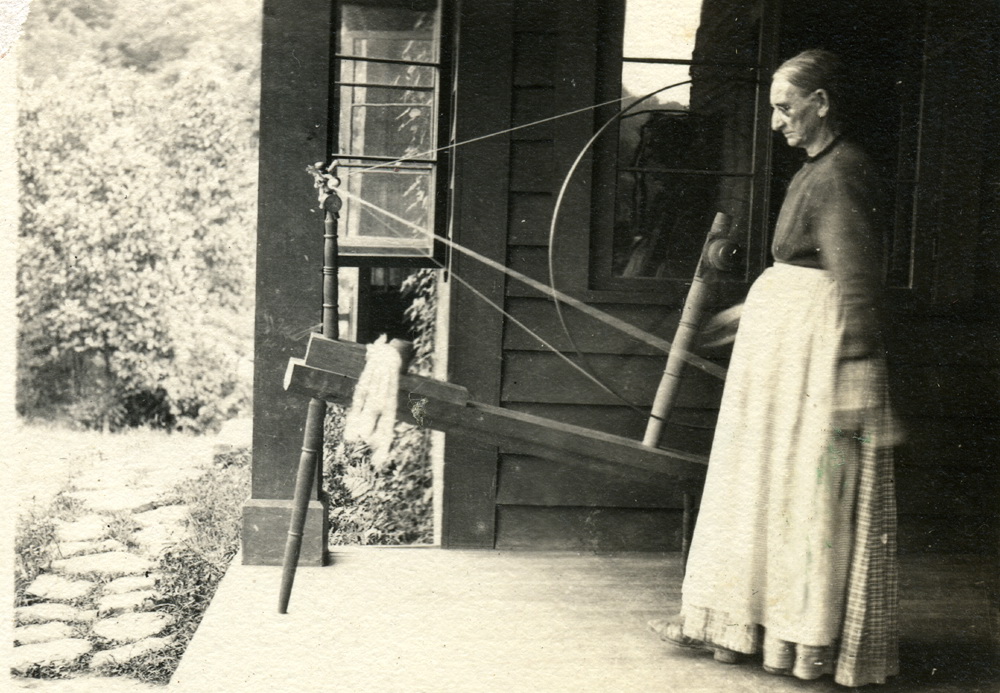

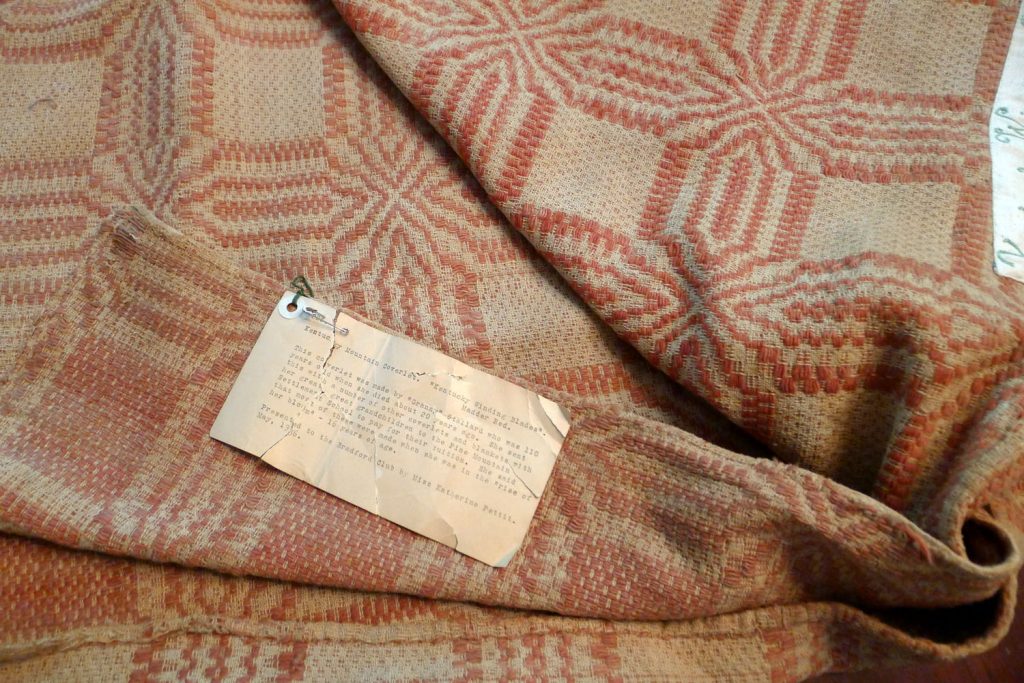

When Katherine Pettit left Hindman Settlement in Knott County near Christmas in 1912, she aimed to establish the Pine Mountain Settlement in nearby Harlan County. She was already familiar with the terrain, having trudged through it many times over the years visiting with mountain families and looking for “kivers” and seeking support for more educational opportunities for the local populations. She had developed a deep respect for the native intelligence of the mountain dwellers and for their craft skills and their self-sufficiency. Her search for “kivers” or coverlets, the handwoven craft of many families, was a personal passion. However, this will to collect woven and other crafts in the area was consistent with a personal tendency to isolate herself from the many changes coming with industrialization.

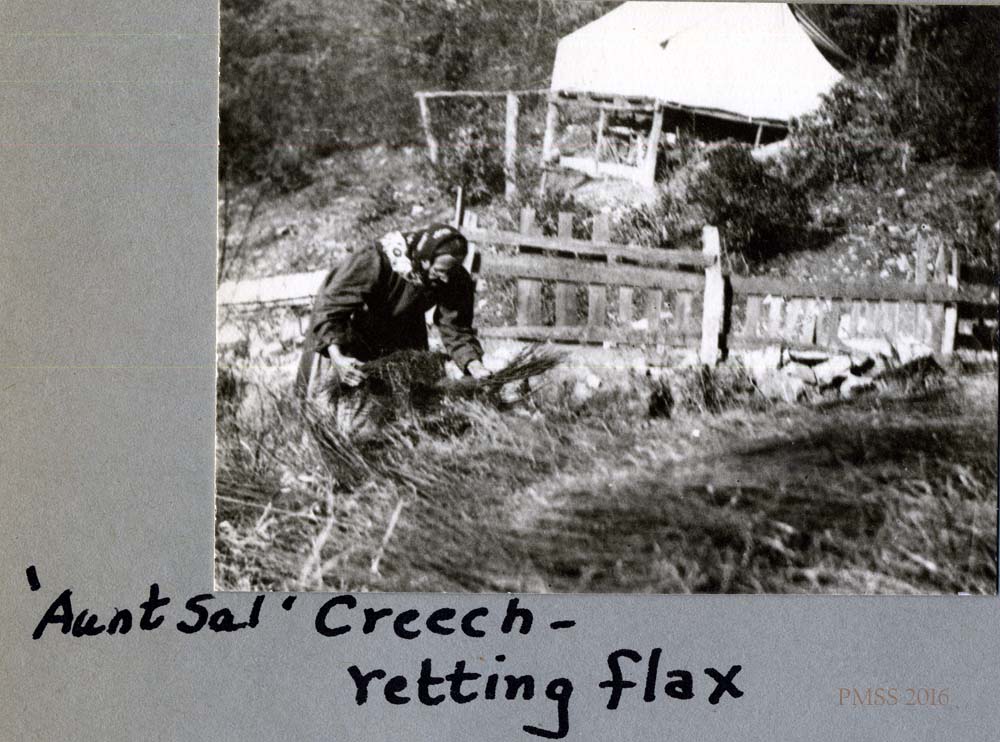

Pettit saw the changes instituted by railways, logging, and mining as a threat to a unique culture and people. She saw in the mountain people a promise for the sustainability of the heritage of the region. In many ways, she saw her role as an “emergency” worker for an underserved and endangered population; someone who would protect the culture while rapidly educating for the coming industrial change. She had witnessed disease, poor health choices, and a lack of educational opportunity devastate mountain communities. But high on her list of needs for the people in this isolated region was medical care and health education. The many diseases that were coming to the area with the growth in timbering, mining and general industrialization, the new railroads, and the growing movement away from the land, she found disturbing. The change would come. She did not doubt that. She believed that education could mitigate those rapid industrial changes, but she also believed a greater threat to the core culture and people of the Central Appalachians were the many diseases coming along with industrial change — particularly in new timbering and coal mining populations.

HINDMAN SETTLEMENT

The health issues of the region were growing when Katherine Pettit and Ethel de Long came from Hindman Settlement to establish Pine Mountain Settlement in 1913. While Pettit and her staff were very familiar with the health issues of the region and had anticipated the increased threat of the coming railroad and growing lumbering and mining towns, they were constantly startled by the persistent primitive conditions in remote homes.

In 1914, the year following Pettit’s departure from Hindman, it suffered a major typhoid epidemic. While the cause, it was revealed, was not that the school was unclean or that nurses were not available to the school and community; it was an infrastructure problem. The School’s toilet system was poorly planned and constructed and had contaminated the water supply. The faulty toilet and water system was a problem that had been pointed out by the State Board of Health in 1912, but the rapid growth of the school and the many costs associated with its maintenance of educational programs were expensive. Further, the existing system was deemed adequate until the large remediation expense could be covered by Hindman’s budget. The operational budget dominated. Typhoid was the result.

The typhoid epidemic at Hindman sickened a third of the adults at the school and almost half of the boarding students. One student died. The failure of Hindman to identify infrastructure (water and toilet) inadequacies and to address them, resulted in both a “health and a pubic relations disaster” suggests the School’s historian, Jess Stoddart [Stoddart, Hindman …p.79]. The health crisis also created a deeper economic crisis for the school as revenues declined by 36%. By 1915 Hindman was questioning if they could continue to exist. Pettit was concerned about her previous school, but she was already at Pine Mountain shaping her own version of the model settlement school. She had brought with her one of Hindman’s most competent educators, Ethel de Long, and recruited other Hindman staff. She was now even more motivated to build a school and community resource that would address some of the short-comings she had seen at Hindman. Medical support and health education were primary building blocks in her plan.

PINE MOUNTAIN SETTLEMENT AND HEALTH PLANNING

Katherine Pettit was a seasoned and meticulous observer and actor on potential problems. She was determined to not repeat the infrastructure mistakes of Hindman in her plans for the new school at Pine Mountain. She placed health services at the center of her proposed programs for the new school and foregrounded health and safety for students and staff at the new school. The physical design of the campus was created with an eye to easy quarantine and she sought the assistance of engineers to advise on toilets and water within the first two years. In conversation with the newly appointed architect, Mary Rockwell Hook, she evaluated potential health issues and long-range growth. Hook, who was charged with the design of the new institution, was a skilled architect and one of the first women architects in the nation. The planning of Hook, Pettit and, co-director, Ethel de Long resulted in one of the nation’s most beautiful and well-planned rural settlement schools in the country.

Health staffing was the important institutional insurance that Pettit immediately put into her planning at Pine Mountain. Part of this insurance plan was Harriet Butler, one of the first nurses at Hindman who was, like Pettit, a person committed to regional health. The insurance plan was a good one as Harriet Butler was also committed to the educational side of health which would produce the optimum long-term outcomes for the people in the remote region. While at Hindman, Harriet Butler and John Wesley Duke, who then served as Hindman’s physician, and also the county medical officer, instituted a vaccination program and gave lectures on various health issues to the community. These talks included how to establish good personal hygiene regimes but early-on provided the community with information on how to deal with contagious diseases. Butler had instituted many of these changes in health care at Hindman, but for her, the changes did not go far enough. Butler was an admirer of the work of Pettit and had been increasingly discouraged with the pace of health education at Hindman. She and others in the region wanted more health education engagement in the community and increased public awareness. Like Pettit, Harriet Butler was an energetic pragmatist like her friend Pettit. At Hindman the staff lamented in their newsletter, “… it seemed as if, however fast we run, we could never keep up with the pace she [Pettit] had set.” They did not realize that Butler would soon follow Pettit to the new school at Pine Mountain. The combination of the two dedicated and energetic pragmatists assured that progress would be rapid.

By 1918 Harriet Butler had made her decision to leave Hindman and by 1919, at the invitation of Pettit, she joined Dr. Grace Huse, a smart and energetic young physician from North Carolina hired by Pettit and de Long. The team of Pettit, de Long, Butler and Dr. Huse was dynamic and their progress was rapid. In essence the process of planning two new health centers associated with Pine Mountain and prospecting for building out to seven more facilities had been percolating since Hindman. Organizationally, Huse and Butler would head the Medical Settlement at Big Laurel and would consult on the development of the Line Fork Settlement in nearby Letcher County and would be medically available to the Settlement School at Pine Mountain. The Big Laurel and Linefork sites were to be created as satellite locations for Pine Mountain Settlement School and were to be focused on medical and health education and industrial training. The staff at both satellites would also work with the local one-room schools to improve their standard educational programs. All programs would be under the general direction of Kathrine Pettit whose base would remain at Pine Mountain Settlement School. The plan was a lofty one. The execution was sobering.

As a doctor and nurse, Harriet Butler and Dr. Huse were a superior pair. They were given the opportunity to build an important model program that Pettit hoped would be replicated in the surrounding counties. Their resulting model at Big Laurel was indeed exemplary but was crippled by cultural obstacles and by the economics of maintaining multiple sites and expenses. Reigned in quickly by the growing expenses, Pettit’s plan for seven new satellite settlements never materialized as exemplary models are expensive —-forward-thinking — but expensive. The cultural obstacles also did not dissolve readily and access to patients and traditional models of medical care were slow to change and could not be pushed.

What was lasting in these initial programs were the myriad new ideas that the experiments introduced into the communities, albeit slowly. The ideas of Butler, Huse, Pettit, and others who took on the health challenge, were positively contagious even as a slow contagion. If it had not been for problems of the economy of scale, and a reliable revenue stream, the ideas of these women might have lasted much longer and adjusted to the in-coming industrial era. Many of the earlier programs and ideas did, however, persist in the later work of other visionaries such as Mary Breckenridge and her internationally recognized Frontier Nursing Service.

WORLD WAR I – “THE GREAT WAR”

By the spring of 1916, another kind of health threat loomed; World War I. Thousands of Appalachians served in this war, and Kentucky had more volunteers in the fight than any other state. Many men and women died in the merciless war and thousands came home with deep wounds both physical and psychological. New diseases also took their toll. Women from Appalachia were eager to join the war effort and quickly drained local resources. Women’s work early in the war as Canteen workers, Red Cross nurses and workers in France and other locations was vital to soldier’s health and morale. Later in the war women held key positions in the hospitals established to care for the sick and wounded both abroad and in the United States. Many of these women were also pulled from the Appalachian region. [See: Brumfield, Nick, The Forgotten Nurses of Appalachia’s Spanish Flu, March 17, 2020. xpatalachians.com]

In addition to health concerns, the Great War also brought on enormous economic concerns. A coal shortage emerged as industry ramped up its steel operations while the domestic supply of fuel for heating and electricity, and for ship and rail transportation stretched the uncoordinated and competitive supply system to a breaking point. In 1917 President Woodrow Wilson asked Dr. Harry Garfield to serve as the Director of a new Federal Fuel Administration and charged him to develop a plan for dealing with fuel shortages, particularly coal. By 1918 Garfield, the son of former President James Garfield came from the Presidency of Williams College to his new federal position. Harry Garfield had a direct connection to the coalfields of Appalachia. He had served on multiple boards that had coal interests, revitalized communities in which he lived, and negotiated many thorny labor settlements as a lawyer. Of important interest to the Eastern Kentucky region and the bituminous coal fields, his daughter, Lucretia Garfield briefly worked for Pine Mountain Settlement School in Harlan County, Kentucky as a community worker in its evolving health and education programs — arriving in 1918. It is clear that she also worked for her father and served as his eyes and ears for local issues, particularly in the important and growing Harlan County coal mines. Unfortunately, her correspondence from Pine Mountain is not available, but likely would be very revealing.

In May of 1918 Frank J. Hays President of the Executive Board of the United Mine Workers of America while meeting in Indianapolis, drafted a letter to Dr. Harry Garfield declaring that the coal production of the country was

“… far below the nations’ lowest possible estimated requirements, and that because of enforced idleness, miners who through their various organizations pledged their full support and co-operation to the fuel administration, are being forced to leave the mines in the industrial centers, where the car shortage [train coal -cars] shows no sign of improving.”

Coal Mining Review May 1, 1918, p. 4

The “forced idleness” was not just in the industrial center delivery points, but affected all coal-related industry, specifically mining of coal in the coalfields. The labor stoppage impacted most of the 500,000 mine workers. Further, the labor shortages brought about by the departure of foreign workers who had flocked to the new mining operations. The growing and severe economic hardship and pressure on the miners and their families in the Appalachian coalfields and coalfields began to be felt and noticed across the country. The “forced idleness” referred to in Hays’ letter reflected the practice of arbitrary pricing of coal that had to be negotiated. The negotiation process then idled workers while lengthy negotiations took place between operators and buyers. The price of coal was never consistent. With no pay coming in for miners while negotiations were underway, the workers could not take care of their union dues, and more importantly their health needs and debts. Many men left mining and those who stayed did so at great peril.

It was a tenuous and fragile economic existence for miners in 1918 and by May it had reached a crisis. There was no clear path as the world began to teeter on the edge of a health disaster. Hays, the UMW President asked Harry Garfield to help the union negotiate the minefield of rogue operators and the growing disregard for the lives of the mining workforce. Garfield set to work, but the journey quickly became more complex than just negotiating labor contracts.

In May of 1918, the War had ended but the residue was just catching up. Following the war, as if the ravages of battle had not taken the lives of enough Appalachians, another threat was building; that of economic instability and an enormous mining workforce weakened by unattended health issues and poor morale.

In 2008 the CIDRAP (Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy) at the University of Minnesota drafted a paper on the crucial preparedness gaps in the United States where electricity and the coal supply meet. The paper asks,

What’s the link between pandemic influenza, electricity, and the coal supply chain? And why should anyone care?

Osterholm, Michael, PhD, MSPH, Nicholas S. Kelley, MSHP, CIDRAP REPORT; Pandemic Influenza, Electricity, and the Coal Supply Chain: Addressing Crucial Preparedness Gaps in the United States, Nov. 2008. CIDRAP, University of Minnisota. [ACCESSED May 30, 2020] https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/sites/default/files/public/downloads/cidrap_coal_report.pdf

The CIDRAP researchers had done their homework and there was good reason to care at the time — as there was in 1918. Today, coal is still crucial and particularly to many underdeveloped countries that depend on supply coming from the U.S., but, the demand for coal in this country is steeply decreasing while the country and the world is deeply dependent on electricity. All the threats cited in the CIDRAP report were present in 2008 and in 1918 and many remain today and are potentially deadly if not addressed.

In 1917 when Dr. Harry Garfield assumed his leadership role in the new Federal Fuel Administration office, his role was vital to the survival of mining and miners but he had not yet encountered the other deadly threat —- a pandemic. Neither he nor the miners could imagine this even greater threat; a mysterious virus — deadly and with no cure. Popularly called the “Spanish Flu” because it was believed to have originated in Spain, the new threat created a storm of suspicion and exaggeration. The name “Spanish Flu” was, first of all, not accurate, but then news traveled slowly in August of 1918.

“Spanish Flu” did not originate in Spain, but its path of death was real with any name attached to it. In reality, the disease first appeared in the army barracks of the United States. The “Spanish” name had come quickly on the heels of an announcement that King Alfonso of Spain had come down with an unknown and untreatable flu or “la grippe.” The King’s illness was widely reported in news throughout the world. The “Spanish Flu”, then became the common name for what was not a “flu” but an H1N1 virus that had its origin in birds. Like the current disease, COVID 19, the “Spanish Flu” was a coronavirus with pandemic written all over it. The virus rapidly spread throughout the world in a manner similar to the current COVID 19 virus and also an earlier epidemic called the Black Death that killed 50 million Europeans in the Middle Ages or some 60% of Europe’s population at the time. The Black Death’s vector, or spreading agent was rats and fleas and it was not the first such outbreak through the earlier centuries.

The common practice of giving pandemic viruses easily recognized names is all too common, but it does little to describe the medical devestation such a virus wreaks on the populations of the world. Today we have linked COVID 19 with China where it apparently first appeared. China did not invent the scourage and blame will not take away its power. Linkage of the 1918 virus with Spain and the current association of COVID 19 with China do little to stop the spread of such virulent diseases. The Black Death described the color of the corpse when affected by the bubonic plague. That is perhaps as personal as “naming” can get.

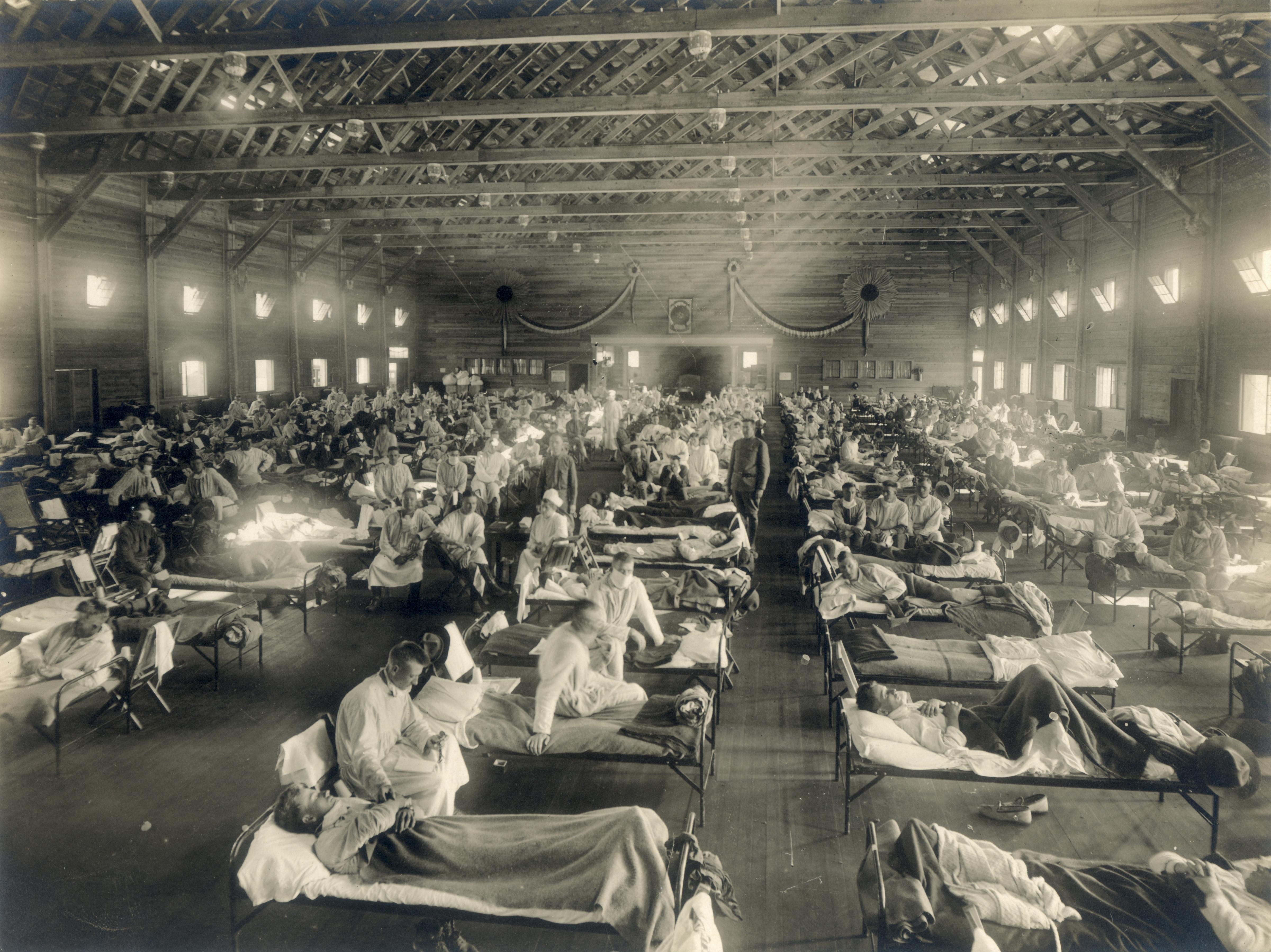

Camp Funston, Emergency Hospital. Otis Historical Archives, National Museum of Health and Medicine / Public domain

Most historic accounts point to the first identification of the 1918 virus in U.S. military personnel. A recent (2005) paper suggests that the first cases were in New York, but a more accepted historic origin was thought to be in Haskill County, Kansas at an Army Camp called Funston. The two H1N1 virus strains , 1918-19 and 2020, are linked by their similarity. There was and is no known medical intervention that will halt the progression of the disease. Like the COVID 19 virus now rampant across the world, the 1918 virus was resistant to treatment and no known vaccinations were on-hand to stop the pandemic. As soldiers and nurses and immigrating Europeans flooded into the United States at the end of World War I, the extensive and busy railway system carried the multitudes of persons back and forth across the country. The 1918 virus exploded in the army barracks, in the cities, and eventually in most corners of America. In Appalachia, the mining communities were the first to be devastated.

As the war in Europe heated up, the coal mines in the Appalachians were frantically mining anthracite coal to supply the need for manufacturing iron for the war and bituminous coal for ships and trains and home heating. In the East, anthracite coal mining was generally centered in Pennsylvania, while bituminous coal was almost exclusively mined in the coalfields of West Virginia and Kentucky. While delivering coal and coke for the war effort, and supplying home heating and electrical needs, shipments of millions of tons of coal crisscrossed the country’s rails and new railroads were created and new laborers flooded in to fill the labor gap. The demand for miners and down-stream workers was enormous and miners came from all areas of the country and from Europe and Mexico and other locations looking for work. But work was demanding and often dependent on an operator’s negotiation of pricing and cars to carry the coal.

Following the common story that the flu spread in the United States with the return of soldiers from the war, the first instance of the disease in Kentucky was reported in September of 1918. The first appearance of the disease had occurred just the month before. In Kentucky the infection has been blamed on a train carrying troops from Texas which stopped at Bowling Green where several army soldiers who were carriers of the disease got off the train and then transmitted the disease to local people in Bowling Green. From there the disease exploded in the regional population and promptly moved into the mountains of Kentucky through the very mobile mining population.

With no vaccines to slow its progression, the world-wide pandemic took hold of the tightly packed and transient mining camps of Appalachia in the late Fall of 1918 and began a deadly march on the lives and livelihood of miners and their families. World-wide the virus left a long trail of death. In 1918 the world population was about 1.8 billion of which an estimated 50 million deaths occurred. That would be approximately 2.7% of the world population. The higher estimate of 50 million deaths would suggest the 1918 virus killed 2.7% of the world population. Though the exact number and percentages are not fully known.

While an exact number count of deaths cannot be tallied, it is known that the death toll in WWI was smaller than the 1918-19 pandemic human toll. Across the country, with the devastation of WWI, still fresh in their minds, the people now found themselves facing an enemy even more frightening than guns and bombs and mustard gas; more frightening than the epidemics of typhoid, diphtheria, tuberculosis, scarlet fever, mumps, whooping cough, and more. The new disease, created dis-ease and fear as it had no face and its weapons were new, stealthy, and deadly.

The 1918 world-wide pandemic lasted until the early summer of 1919 and while short-lived, it is estimated to have infected over 500 million people, approximately one-third of the world’s population. Of this infected population, some 50,000,000 or more died of the virus, or, according to other data gatherers, some 3%-5% of the world’s population. No matter the incomprehensible numbers, Appalachians soon found that the world was smaller than they had imagined and that they were not as isolated as most in the Appalachian region believed to be the case.

COAL TOWNS AND THE 1918 PANDEMIC

Appalachia in 1918, was both fortunate and unfortunate with regard to the influenza pandemic. Kentucky death estimates are believed to be in the range of 14,000 deaths, though the exact number will never be known. The death registers of funeral homes often listed the cause of death as pneumonia but the course of the disease which resembles the current respiratory distress path of COVID 19 is often defined as a type of pneumonia. While the death records are difficult to untangle, they tell an unfortunate story that centers on the devastating toll the 1918-19 virus took on the crowded mining towns in the coalfields of Appalachia. The fortunate story is in the remote hollows and the sparsely populated agrarian or subsistence farming valleys of the region. There the story is one of social distancing.

Today we are looking at race and ethnicity in our data tracking of the COVID 19 deaths. In 1918-19 there was no consistent account kept of the race and ethnicity of miners and families. The Immigration Act had just passed in 1917 which required a literacy test for immigrants from the southern and eastern European groups, that aroused suspicion as the war in Europe heated up. Author Mina Carson tells us in her well-researched book Settlement Folk: Social Thought and the American Settlement Movement 1885-1930, (1990) that when the U.S. entered the war, “new legislation was proposed to coerce ‘100% Americanism’ by eradicating all signs of immigrants’ lingering loyalties to their native countries. The National Federation of Settlements was opposed to this government action suggesting that such an action would breed “misunderstanding and bitterness.”

Mary McDowell, a Kentuckian and leader in the Settlement Movement was a friend of Pine Mountain Settlement School’s Director, Katherine Pettit. McDowell’s co-worker, and Settlement Movement leader, Mary Simkhovitch, and many others in the movement opposed the use of such terms as “Americanization” and instead aimed for what they called “transnationalism” or the concept of a “new kind of nation of many peoples ‘whom God hath made of one blood.'” [Carson, p.159] This sentiment was to be heard often from Berea College, a Kentucky school founded in 1855, and a long-time advocate for the people of Appalachia as well as the world. The college motto: God hath made of one blood all peoples of the earth (Acts 17:26)” Is remarkably close the transnationalists.

Pine Mountain Settlement did not enter into this “transnationalism” debate directly, but later history demonstrates that many within the School who had served as missionaries or medical workers abroad understood the threat of coerced acculturation and its possible potential for ethnic cleansing such as that seen in Armenia. [See: Edith Cold, English Teacher]. The program at the School and its mountain founder William Creech strongly evidenced the commitment to “peoples acrost’ the seas.” [See Uncle William’s Reasons]

In 1914 when WWI began, many of the miners in the coalfields were immigrants. They had hired-on in the booming years in the coalfields of the Appalachian mountains. Many immigrants came just for this economic opportunity. However, as more and more countries in Europe were pulled into the growing European war, many immigrants fled the War. Yet, many were pulled by patriotism back to their country of origin. The need to fight the war in their homelands was a noble action, but the impact on mining in the American coal fields was devastating as miners headed “home” and new immigrants headed for the cities.

By 1917 those immigrant miners who chose to remain in the United States and who fought with the American Expeditionary Forces numbered near one million. Also by 1917 many foreign-born males were required by law to register between June 5, 1917 and September 12, 1918 with the government. Most of the foreign males required to register were from the following countries

| NATIONALITY | NUMBER | PER CENT |

| Austria-Hungry | 751,212 | 19.38 |

| German Empire | 158,809 | 04.09 |

| Turkey | 81,608 | 02.10 |

| Bulgaria | 19,873 | 00.52 |

| TOTAL ENEMY ALIEN MALES | 1,011,502 | 26.38 |

From numbers compiled from the Foreign Language Information Service of the American Red Cross, it is also known that nearly one million immigrants from the following groups joined the American Expeditionary Forces to fight in the Great War

| NATIONALITY | NUMBER | KILLED |

| Italian | 300,000 | 4,000 |

| Jewish | 250,000 | 3,500 |

| Polish | 170,000 | ? |

| Czechoslovak | 125,000 | 2,000 |

| Greek | 60,000 | ? |

| Lithuanian | 35,000 | 500 |

| Jugoslav | 20,000 | ? |

| Russian | 20,000 | ? |

| Ukrainian | 18,000 | 500 |

| Hungarian | 7,000 | 200 |

| TOTAL | 985,000 |

German immigrants of German birth were not listed but were estimated to comprise between 10-15% of the American Expeditionary Forces according to the War Department. Males engaged in mining between the ages of 18 -45 comprised a significant proportion of the figures on the two tables. Interestingly, mention is not made in these statistics of the large number of Mexican miners who were engaged to fill vacancies in the mining operations. In 1919 this brief note appeared in the Mining Weekly stating

No more permits for the importation of Mexican labor, which has been used to considerable extent by bituminous coal operators recently, will be granted, the Labor Department announces, and permits already granted will be void after January 15. Mexicans permitted to enter the country temporarily for war work will be “repatriated gradually,” but there is no intention to deport such laborers.

Mining Weekly, 1919.

President Wilson’s announcement of “no more permits,” had been misinterpreted and there was great fear that deportation would start immediately. The enormous contributions of immigrants during the years of the Great War and during the Spanish Flu epidemic are seldom recognized but they often made the difference in maintaining both economic productivity and security and bolstering the American Expeditionary Forces.

The immigrant departures, internments, and injustices just as the war was ramping up and again as it was winding down and while the nation was faced with a pandemic are often overlooked, but there are many descendants in the Appalachian coalfields who still remember. The increasing demand for coal to fire the steel mills energized an economic emergency created by a labor shortage. Of those who left at the beginning of the war to fight for their countries, not so many returned to America at war’s end to resume work in the coalfields of Kentucky, Virginia, Pennsylvania and, West Virginia. At first, this exodus was an economic catastrophe played out in a labor shortage but little has been made of those immigrants who left to fight as patriots in the Great War. There is no debate, however, that when the pandemic infection took hold in the coal camps, it did not look at race, ethnicity, or patriotism and the human and economic catastrophe escalated in scale and misery.

As the virus took hold in the tightly packed coal camps, the crisis in the coalfields was not blamed on foreigners or foreign infection but was recognized as a problem that was home-grown and familiar but was incomprehensible in scale. The rapid infection-point of the virus could be directly associated with poor hygiene, a distracted population, and the slow-to-act or greedy industrial elite. The infection blame point was more insidious and blame was rarely sought and infrequently handed over to political rivalry.

Strangely, when the disease swept through the camps, it did not target the weak but was particularly deadly to a population that was thought to be the healthiest. Adults between the ages of 20-40 years of age died in great numbers. Men with weakened lungs from coal dust were remarkably susceptible. An unusual number of young Caucasian women also seemed to be particularly vulnerable. The death toll of both sexes was enormous in the mining towns and camps of Eastern Kentucky. One observer noted that in one camp he visited there were coffins on nearly all the porches in the camp placed there for those struck down or waiting to die from the virus. Finding able-bodied men who could dig graves was also a major problem for production as the maintenance of a work schedule at the mining camp could not be maintained nor enforced. Miners in the affected camps were rapidly becoming sick or assisting with the burials of family or neighbors and family. These efforts took precedence over the mining. In addition to the squabbles regarding coal pricing instability, the coal economy began to further deteriorate.

The rapid burial practice in the rural areas of Kentucky also had another side-story. The push for quick internment created tracking issues as there were insufficient records being gathered in the time of crisis and assembling an exact number for those who contracted the virus and who died of the pandemic was difficult to pull together and target. Most authorities who have looked at the mortality data from the eastern coalfields doubt its cumulative totals. It is likely that the numbers that were finally put together and that are fixed in the historical record were well below the actual deaths that occurred during the 1918-1919 years.

Remarkably, while history has not recorded those difficult years in a comprehensive and efficient manner, it has quickly forgotten the lessons of the pandemic. While few families in the Eastern coalfields escaped the contagion and the harsh suddenness of death and loss of a loved one, the historical record for the region is very slim and warrants only a brief treatment in history books about the region.

HARLAN AND CONTAGION IN THE COAL CAMPS

In Harlan County, the coal camps were running enormous mining operations in the 1916’s and 1917’s. The imperative to supply the war effort continued to be extreme and men and machines were pushed to a breaking point when contracts were settled. There were coal operators who tried to strike a balance in the enormous demands placed on their operations and there were others who saw their profits soar and felt no obligation to share the accruing wealth with their workers — many of whom were foreign-born. But there were exceptions to the rule of most coal camps. The exceptions were largely those operations that were well funded by mega-corporations. For example, great care had been given to infrastructure at Inland Steel’s company town, Benham, and at the International Harvester’s coal camp at Lynch, and at a handful of other well-run camps. These camps set an example for a high level of sanitation, pay, and for their medical support.

These two towns in Harlan County, Benham, and Lynch, were models of health care, and, in later years when Pine Mountain encountered medical emergencies they could not meet, they often called on the physicians and services available in the two coal camps. In the 1918-19 pandemic, the numbers of dead at the efficiently managed towns and camps were not as great as those that failed the health needs of their populations. Still, mitigation of the new “flu” created failure after failure. The bottom line was that in the pandemic of 1918-1919, common protections and practice and skilled medical knowledge were sometimes not enough, especially in densely populated centers.

By 1932 many of the coal camps in Harlan County were still lagging behind in their commitment to health needs and the grave health needs and great disparity within the county of Harlan are clearly documented by the study of health needs conducted by Dr. Iva M. Miller for the Save the Children Foundation in the 1932 Health Survey of Harlan County, Kentucky —just 12 years following the pandemic.

The scenario of the entry of the 1918 pandemic into Harlan County can be traced from a record of one of the earliest coal towns of Appalachia, Kaymoor in West Virginia. It was here that the story of the contagion played out so cruelly and that under-scores the tragedy of close-living, inadequate hygiene, and managerial and economic insensitivity. It is a story that became all too familiar in the coal dominated economy of the Central Appalachians in the 1918’s – 1920’s. Many coal towns like those of Kaymoor became the vectors for the pandemic in the surrounding region.

Kaymoor was one of the first company coal towns. Belonging to Lo Moor Iron Company, the coalmining operation supplied its black gold to the pig iron plant of Lo Moor Company located near Clifton Forge, in Alleghany County, Virginia. Abiel Abbot Low, a wealthy investor, and owner of the Lo Moor Iron Company, was a board member of the C&O rail line which was the new and only access to the Lo Moor Iron company and to its rich iron deposits. Abiel Abbot Low owned four thousand acres of iron ore in Alleghany County, Virginia, and the associated rail line linked to the southern West Virginia coal country where he had purchased eleven-thousand acres of coal land in Fayette County, West Virginia. With his transportation system in place, he then proceeded to build out his empire by establishing a series of coal town communities. The cooperative communities, aggregated under the name Kaymoor were begun in 1899. A full description of the Kaymoor communities may be found in Crandall A. Shifflett’s informative and deeply researched book, Coal Towns: Life, Work, and Culture in Company Towns of Southern Appalachia, 1880-1960 (pp. 38-40).

When the Spanish Flu and other diseases came to Appalachia, the closely packed coal towns, such as those like Kaymoor, were the most vulnerable sources for infection. The Spanish Flu was not the first epidemic to strike Kaymoor. It was particularly suited for infection. First it was smallpox in 1904 which was addressed by the community physician by inoculation — but not for all. When the company realized that inoculation would cost $60,000.00 to include all in the community, they parceled out the shots to those who could afford to pay or were cronies. It was selfish and a deadly mistake. The epidemic took off. It quickly killed hundreds of miners and their families. When the Spanish Flu arrived there was no vaccine to quibble about and the Company, guided by the large fatality numbers in the smallpox epidemic, mandated what is now call “Social Distancing.” Shifflet tells us that there were

“… drastic curtailments of activity to prevent its spread. Schools were closed, the theater was shut down, only one customer at a time was allowed in the barber shops, and all public meetings were discouraged as company doctors at Kaymoor One ‘… worked day and night to prevent the inexorable spread of the deadliest influenza epidemic in American history.’ “

Shifflett [p.56] notes the following correspondence as his source: E.R. Price to Dr. Don J. Schleissmann, Public Health Service, series 7, box 17, Wheelwright Collection, King Library, University of Kentucky, Lexington.

Their efforts were, however, too late. It is interesting that the physicians of the day and even later historians initially blamed the Kaymoor pandemic infection on the water supply and the lack of adequate sewers, not realizing until too late that the main culprit was human contact. The failure to grasp the transmission process was at first not unusual, as there were so many diseases in the coal camps that were caused by poor hygiene and by inadequate water and sewage systems, like that seen earlier at Hindman School. But, while the new disease was not directly associated with personal hygiene its spread was eventually determined to be directly tied to a personal hygiene regime — especially hand-washing. So many of the diseases in Appalachian communities could be and were directly associated with poor personal hygiene and inadequate health education and poor medical support systems. But the Spanish Flu, like the current COVID 19 was unfamiliar and more elusive in its contagion process.

QUARANTINE AND PINE MOUNTAIN SETTLEMENT SCHOOL

Outside the coal camps and the towns and cities in Harlan County, associated with the mining of coal, the 1918 contagion found that it had to fight a myriad of stubborn obstacles. One of them was Katherine Pettit — a force to be reckoned with. She reported in a note to a Pine Mountain Board of Trustee member, Mrs. Morton, who lived in Lexington, Kentucky, that while the flu was all around Pine Mountain School, it [the School] was untouched. She writes

Dear Mrs. Morton,

It was so good of you to be anxious about us … We have no influenza now, though it is still around us. Three-hundred have died in Harlan County, I hear …

Pettit, Katherine. Letter to Mrs. Morton, PMSS Collections. [pettit_1918_007.jpg] November 13, 1918

As Katherine Pettit relayed in this note to Mrs. Morton, Pine Mountain was spared the ravages of the 1918 pandemic. If any reason may be pointed to, it would be that the School had practiced quarantine many times in the past.

Katherine Pettit writing to her sister “Min” on November 8, 1918, notes that

“…tomorrow Miss Gaines [Ruth Gaines], comes from Massachusetts, and Miss Parkinson from Kansas. They are all to be isolated in Miss Butler’s house up on the mountain until we are sure they haven’t brought influenza. And I am wishing you could come now, and do the same thing…”

Letter: Katherine Pettit to Mrs. Waller O. Bullock, 8 November, 1918. PMSS Archive. Pettit Correspondence 1918. [pettit_1918_009.jpg]

Evelyn Wells writing about the pandemic in 1928 in her RECORD OF PINE MOUNTAIN SCHOOL 1913-1928 remarked that

Quarantine of the School in the fall of 1918 prevented a single case of Spanish Influenza from breaking out, though neighbors, showing a low immunity, were ravaged This was a most effective lesson to everybody on the value of quarantine. We have not always been as fortunate in keeping out contagious diseases and measles (1920, Boys House needed to take care of the 40 cases), mumps (worst in 1926, when they overflowed to the Country Cottage) and whooping cough (1924) have been our worst epidemics. There have been two deaths from sickness, among the children of the School. In 1923 Harry Callahan died of spinal meningitis resulting from severe injuries to the head when he was thrown from a moving train, and in 1924, James Gilbert died, also of spinal meningitis. There has been a steady decrease in colds and minor epidemics as underweight children have been built up by extra milk, rest [and] other special care, which has reacted upon the[ir] physical vigor.”

Wells, Evelyn. Wells Record 11 PMSS Health 1913-1928. Unpublished early history of Pine Mountain School that includes an outline of health care at the School from 1914 to 1928.

As reported by staff member Evelyn Wells in December of 1918

“And, influenza everywhere, though no cases at the school yet. Only one or two children are going home for vacation. We are rigidly quarantined, an object lesson we hope for the whole countryside.

Wells, Evelyn. 1918 Excerpts from letters home. Decembre 19, 1918. [050-p.6]

Influenza, typhoid, diptheria, gun-shot wounds, snake bite, birthing babies, teaching children how to brush their teeth, wash their faces and hands, how not to hold the water dipper over the water bucket as they drank from it, teaching food preservation, food storage, how to bandage a wound, which herbs were harmful, which helpful …. the list is a long one in the diaries and letters of the nurses and doctors who worked in the two medical clinics that were managed by Pine Mountain Settlement. The first-hand accounts of treating a wide range of medical issues give some sense of the demands placed on those medical doctors and nurses who served the Pine Mountain Valley and beyond from the two clinics that were established to the east of the Pine Mountain Settlement School in Letcher County and to the west at Big Laurel on Greasy Creek. A Red Cross nurse, Frances Palmer, who had survived WWI and the 1918 pandemic came to Pine Mountain to assist with the development of two satellite health centers at the School in 1920.

FRANCES PALMER CONQUIST

Frances Palmer (Conquist) only stayed at Pine Mountain for six months before returning to Minnesota to be married. She was one of the first nurses to be placed in the new health settlement at Line Fork, in the neighboring county of Letcher. She describes an incident remembered from one of her tasks at the Line Fork Settlement which involved the removal of bullets from a young man caught up in a local feud. The Frances Palmer story is a short but revealing tale of a small Eastern Kentucky community at Line Fork and Frances Palmer’s lessons learned in the horrors of WWI in France. There, in the later years of the war along with 23,800 other Red Cross nurse volunteers, she treated soldiers injured by trench and gas warfare. These war injuries were some of the most ghastly of that merciless war. It was a new challenge and Frances Palmer was heroic and she excelled. In 1919, as a Red Cross nurse, she won a commendation from General Pershing for her “conspicuous service at Chateau-Thierry and at St. Mihiel”, two of the hospitals serving the most vicious battles fought by Americans serving in the war. She later worked in Coblenz, Germany as the war came to an end. There she again, she demonstrated her superior nursing skills while taking care of the multitude of gravely wounded and disabled soldiers. WWI was one of the most brutal wars in history. Frances Palmer lived it. When Frances returned home, it was to a country devastated by a pandemic but she volunteered to come to Eastern Kentucky to address another war that was being waged in Eastern Kentucky. A public health crisis that was evolving there and it had reached the attention of the nation. Experienced and in-experienced women workers looked to their own country and many came to the Central Appalachians..

Like Katherine Pettit, Frances Palmer was committed to serving the needs of the country’s health. A practical idealist, she had demonstrated that she could tolerate difficult environments and that she could do so at grave danger to herself and with courage that was commendable. Her service to the health of her country was a commitment made by so many other women serving in the Red Cross corps.

This is Frances Palmer’s brief account of one incident in her service to the Line Fork Settlement, a satellite health and education center near Pine Mountain Settlement School. A bullet-wounded young man …

It seems that several attempts had been made to “git” one of the young men of the community; and one Sunday night when he was alone in the store at Bear Branch [page 10] some one fired at him and filled his back and side full of shot. Word was soon brought to us, and Miss Dennis and I hurried to the store, where we found him lying on a cot. Most of the shots were superficial, but they were numerous. Nancy, who lives near the store, held the only light which was a miner’s lamp; and in the midst of first aid she fainted, and left me in the dark! Soon the light was burning again and after poor Nancy had had several dippers of water poured over her, she was ready to help again. I tried to persuade them to call a doctor, but they did not think it necessary.

TO READ MORE: Frances Palmer Conquist, 1920, Line Fork Notebook, p. . Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections.

For six or seven days the patient stayed at the store, as he lived some distance up the mountain side. Dressings were changed twice a day, and each time, more shot would be removed. When time came for him to go home, several of the boys cut two tamaracks, cleaned the trunks, and made a stretcher from a quilt and coats: they then carried him up the mountain to his cabin where he was confined to his cabin and bed for several weeks. Between his banjo and book and magazines from the settlement, time passed quickly until he was up and about again.

Another health tale from Frances Palmer.

On my way home from this place, I was called to see a “risen” [boil] on a girl’s arm. She had had it for weeks, and the poultices of red sumac root, or apple and vinegar, of lim [?] root and sweet milk, of buckeye bark and cornmeal, and of hot oatmeal, did not seem to help it. All I could do at this time was to show them how to use the hot salt packs and say I would return in the morning. The next day I applied glycerine and gauze dressings and was informed that they didn’t like the salt packs and had put Vick’s salve on. [When I came to apply] the third poultice I found the oatmeal poultice on again and was almost ready to give up. But the girl had lost so much sleep and was in such pain, that she finally consented to have it opened and glycerine applied again. The next visit found things as I had left them and the “risen” draining well with the patient free from pain.

Frances Palmer Conquist, 1920, Line Fork Notebook, p.4 . Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections.

Pine Mountain Settlement is remote. It was spared the rapid infection seen in the close living of the coal camps in Harlan County. This was because a quarantine was initiated. “A stay at home mandate.” The community of Pine Mountan Settlement reflects a history of valuing the quarantine of infected persons and all the health benefits that go along with it. Quarantine is now a medical necessity in a virulent epidemic. Pine Mountain is a remote community, but it is a disciplined community. The people know how to survive hard times. Social distancing has been the lifestyle in the mountains of Eastern Kentucky for most of its history. Social distancing is in many ways not a mandate but a social pride that people enjoy. Social distancing is a solitude and an independence not found easily in urban environs. Most of Harlan County is now a rural culture well-versed in survival and “make-do” though less so than in years past. But, what remains within the culture of the families of the area are the memories of hard-times and the “make-do” of parents, grandparents, and relatives. Rural America, generally carries this recent memory of the skills to survive hard-times. What is less certain is how the current pandemic will test those skills of rural America including Appalachia and how that divide — rural and urban — will be re-shaped by surviving this hard-time.

Today, courage equal to that shown by Frances Palmer Conquist, is tbeing shown by many health professionals in this country, and by the many workers in Doctor’s Without Borders, workers for WHO, and a multitude of other health care providers here and abroad as they engage the hidden enemy of COVID 19. Today, when we social distance it is women and men like Frances Palmer and her cohorts that WE need to protect with masks and with respect. This is — and it should be — our contribution to this war against the hidden enemy, COVID 19. Wearing a mask and remembering that the six-feet needed for social distancing is our respect for quarantine and for each other. It is not too much to ask in “hard-times.”

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brumfield, Nick, The Forgotten Nurses of Appalachia’s Spanish Flu, March 17, 2020. xpatalachians.com

Emergency Hospital [Image] https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Emergency_hospital_during_Influenza_epidemic,Camp_Funston,_Kansas-_NCP_1603.jpg [Accessed May 31, 2020]

Carson, Mina, Settlement Folk: Social Thought and the American Settlement Movement 1885-1930, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1990.

Coal Mining Review and Industrial Index , 1918, 1919 [google.com]

Conquist, Frances Palmer, Line Fork Notebook, n.d. [1918], Pine Mountain Settlement School Archive, Pine Mountain, KY.

Crandall A. Shifflett, Crandall A. Coal Towns: Life, Work, and Culture in Company Towns of Southern Appalachia, 1880-1960.

Garrett, Thomas A. Economic Effects of the 1918 Influenza Pandemic,

https://www.stlouisfed.org/~/media/files/pdfs/community-development/research-reports/pandemic_flu_report.pdf [Accessed May 10, 2020]

Holden, Arthur C. The Settlement Idea A Vision of Social Justice, New York: McMillian, 1922.

Osterholm, Michael, PhD, MSPH, Nicholas S. Kelley, MSHP, CIDRAP REPORT; Pandemic Influenza, Electricity, and the Coal Supply Chain: Addressing Crucial Preparedness Gaps in the United States, Nov. 2008. CIDRAP, University of Minnesota. [ACCESSED May 30, 2020] https://www.cidrap.umn.edu/sites/default/files/public/downloads/cidrap_coal_report.pdf

Wheelock, David C. What Can We Learn from the Spanish Flu Pandemic of 1918-19 for Covid-19?, Economic Synopses 2020/05/18

https://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/economic-synopses/2020/05/18/what-can-we-learn-from-the-spanish-flu-pandemic-of-1918-19-for-covid-19

SEE ALSO:

1932 HEALTH SURVEY OF HARLAN COUNTY, KENTUCKY

![005a P. Roettinger Album. "Country [?] Looking from Uncle John's toward the School."](https://pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/roe_005a_mod-1024x769.jpg)

The isolation of the region was slowly but dramatically altered by roads, particularly

The isolation of the region was slowly but dramatically altered by roads, particularly