Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 09: BIOGRAPHY

Series 30: MUSIC AND DANCE

Cecil Sharp (1859-1924)

Maude Karpeles (1885-1976)

Visit to PMSS 1917

Cecil Sharp. [Cecil_Sharp.jpg]

TAGS: Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles Visit to PMSS, Cecil J. Sharp, Maud Karpeles, Kentucky Running Set, ballads, Far House I, Far House II, Ethel de Long Zande, Katherine Pettit, American Folk Dance Society, English Folk Dance Society, folk dancing, John C. Campbell, Olive Dame Campbell, Mary Neal, transcribers, English Suffrage Movement, Evelyn Sharp, suffragists, folklorists, settlement houses, Morris Dance

CECIL SHARP AND MAUD KARPELES Visit to PMSS, 1917

In 1917 Cecil Sharp and his assistant Maud Karpeles came to Pine Mountain Settlement School for a visit. Only five years since the founding of the School, the visit was one of the most important events to occur at the School. Their time at Pine Mountain has been memorialized in many accounts, most notably in that of Cecil Sharp himself. What Sharp described was a magical evening where he witnessed a dance that changed his understanding of the relationship of English Country dance to folk dance in America.

THE KENTUCKY RUNNING SET

It was on the terrace of Far House I that the two visitors witnessed the Kentucky Running Set being performed. The event marked a milestone in the revival of folk dance in America. It was here that Cecil J. Sharp and Maud Karpeles witnessed a dance far outside the English Country Dance repertoire and which became a cornerstone of their exploration of dance in the Southern Appalachians.

The Kentucky Running Set as a dance form was probably not unique to the community just around Pine Mountain Settlement School, but it was certainly well practiced in the community. Some say that Sharp and Karpeles had heard of the dance but had never witnessed it until the Pine Mountain School student’s performance. What they saw and later recorded in their notes was that the dance form would forever couple English country dancing and the dance forms of America’s Appalachian region in their folk dance literature.

“Back view of Far House.” Birdena Bishop Album. [bishop_08_004.jpg]

HISTORIC ROOTS

Whether the dance the pair saw at Pine Mountain School was a latent version of some unadulterated early English dance form or a fast hybrid of the quadrille or some other Southern square dance formulation, the “Running Set” captured the imagination of both Cecil Sharp and his transcriber assistant, Maud Karpeles. An astute and full discussion of the “Sharp Legacy,” and the origins of the Kentucky Running Set may be found in the recent (2015) book, Southern Appalachian Hoedowns, Reels, and Frolics: Roots and Branches of Appalachian Dance, by North Carolina dance historian, Phil Jamison. Jamison and others have suggested that Sharp’s authoritative evaluation of dance and music in the Southern Appalachians may need additional research and expansion.

The event, however, stuck in the memory of Sharp and the legacy of the School and was entered into the first and the enlarged editions (1932) of Sharp’s research work, English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians. Two modern accounts of the event are available elsewhere in the archives: an article by James S. Greene III that appeared in the January 1996 Pine Mountain Notes at https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=47238, and an account by Peter Rogers from 2000 at https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=46978.

Both accounts suggest that Sharp had heard of the Kentucky Running Set in his research trips in America, but had dismissed the form as “uncouth.” He surprised himself by his admiration of the performance and later described the dance in a letter to Mrs. J. J. Storrow, an American philanthropist who was interested in American folklore and who had shown an interest in Sharp’s work. It was her gift of $1,000 in 1915, that subsidized Sharp’s collecting venture into the Appalachians.

I came across a most wonderful dance the other day called The Running Set. It is a form of circular country dance of a type about which I know nothing. There is certainly nothing of the kind in England at the present day and there is nothing that I know of in any of the old dance books. It is a very strenuous dance for six couples and extremely complicated. In many ways the general affect [sic] was not unlike that of the Sword-Dance … When I have mastered it and analyzed it, it will probably throw a flood of light on the evolution of the English Country Dance.

When Sharp’s book English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians was launched at the New York headquarters of the Russell Sage Foundation, Sharp gave a lecture to the admiring crowd, and he also provided a demonstration of the “Kentucky Running Set.” He described the event in his correspondence as the “first indigenous American folk dance ever collected.” [Note 28: Shapiro, p.305] This view would later have its many critics.

Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles Visit to PMSS:

THE DEVELOPMENT OF A CURMUDGEON

Cecil J. Sharp (22 November 1859 – 23 June 1924) has been characterized as meticulous in his craft, a curmudgeon, a misogynist, a manipulative and a possessive personality, among other derisive characterizations such as having a “pachydermatous spirit and insidious bedside manner.” [as quoted in Scherman, p. 176]. While his persona is not nearly as interesting to scholars as are the treasures he coaxed from his subjects and passed along to the ages, a look at Sharp and Karpeles as individuals is critical to understanding the importance of Appalachian music and dance to many aspects of life in the Southern mountains.

Sharp tells us that his journey to America was “simple chance.” One of his biographers, Michael Yates, has given us a unique body of information that captures Sharp as a person. In his thorough research, now available since 1999 on the web in “Cecil Sharp in America,” Yates has carefully explored the Sharp and Karpeles correspondence and other resources particularly those that reside in the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library of the English Folk Dance and Song Society, in London. This author and Pine Mountain Settlement School are indebted to Yates and to the Vaughn Library for some of the personal selections that begin to capture both the era of Sharp and Sharp, the man. Here, Sharp is writing to George Parmly Day, President of Yale University Press in 1917

Chance brought me to America in the early days of the war [WWI] … and while here Mrs. John C. Campbell of Asheville, NC told me that the inhabitants of the Southern Appalachians were still singing the traditional songs and ballads which their English and Scottish ancestors had brought out with them at the time of their emigration.

In England Sharp had become disillusioned with the direction of English folk music, seeing it unduly altered by contemporary music and by the encroachment of German musical influences. He devised a series of lectures that gained popular attention and consultation requests. Most likely he came to America first in 1915 as a consultant for Granville Baker’s production of Shakespear’s Midsummer Night’s Dream. Also, in 1915 he was asked to give a lecture on ‘English Folk Song’ at Carnegie Music Hall in Pittsburgh and other locations. When Olive Dame Campbell learned of the noted scholar’s presence in America she made arrangements to meet with him in Boston. At first dismissive, Sharp soon grasped the enormity of Campbell’s collection.

BACK TO ENGLAND

When Sharp left the United States to return to England he carried with him the notation and lyrics of hundreds of Appalachian ballads and songs, including those of Olive Dame Campbell. These formed the foundation of his English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians, published in 1917 (New York: Putnam), a collection that ballad authority Bertrand Bronson named as the “best regional collection we shall ever get.” The 1932 publication included 274 songs — ballads, songs, hymns, nursery songs, jigs, and play-party games and 968 tunes. The collection was gathered between 1916 and 1917 from traditional singers in the mountains of Virginia, North Carolina, Kentucky and Tennessee.

In his search for “authenticity,” Sharp ignored singers of color. There were only two instances of songs collected from African Americans and for this reason it does not seem a “foundational collection of American folk music” but rather a comprehensive body of Anglo-Saxon renditions of English heritage. Many of the “authentic” songs and singers Sharp encountered in the Appalachians were re-birthing of encounters Sharp had in the many English countrysides he visited in England. See for example his collection of a sheep shearing ballad that carries an almost universal theme as described in DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH Sheep Shearing and Cecil Sharp.

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

A graduate of Cambridge in 1882, Sharp did not find his intellectual passion until late in life. In 1893 after a short stay in Australia, Sharp returned home to England and married Constance Dorothea Birch and the couple had four children. By 1896 he had settled into a part-time job as the Principal of the Hampstead Conservatoire of Music. His stay with the Conservatoire was apparently contentious and short and he left in 1906 and with his departure, he forfeited his right to housing at the Conservatoire.

This was obviously a period of personal upheaval but by 1899 at the age of 40, he had discovered his delight in English balladry and folklore and quickly his avid interest enjoined the growing national interest in folk music and dance. After his departure from his Hampstead position he was free to put his entire focus on his avocation and by 1915 he had captured the admiration of England by his dogged determination to collect England’s folk music and dance heritage. It is reported by one chronicler, Tony Sherman, that he collected over 3,300 English tunes from households across the countryside. During this process, he also found time to found the English Folk Dance Society and to lecture on his interests and discoveries.

When WWI broke into Sharp’s quick rise to fame in England, he turned his attention to America where he saw an opportunity to ride the crest of the American folk revival and connect with the American settlement movement. With his collaborator, Maud Karpeles, a transcriber, Sharp left for a busy lecture circuit, landing in the Boston home of the American headquarters of the English Folk Dance Society and one of the country’s leading settlement house cities.

Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles Visit to PMSS:

THE RUSSELL SAGE FOUNDATION, JOHN C. & OLIVE DAME CAMPBELL

Another organization with roots deep in the folk culture movement was the very active Russell Sage Foundation. At the time, the Foundation was stimulating interest in the Southern Appalachian region of the country which had become the new focus of social reform. Attention was turning from the training and support of the Negro freedman and becoming concentrated on the “poor Appalachian white.” Concerned for the social and economic plight of many families in the mountains of the Southern Appalachians, the Russell Sage Foundation established an office in Asheville, North Carolina. Headed by John C, Campbell the office pursued the interests of the Foundation with sponsored research and information gathering on the little-understood region. While in Asheville, John C. Campbell also founded the Council of the Southern Mountains and its annual conferences that brought together social services, religious organizations, and crafts organizers. During this time, the first decade of the twentieth century, John C. Campbell spent many days in the Appalachian mountains traveling with his wife Olive Dame Campbell. His fieldwork stimulated interest in the social life and folk heritage found in the deep pockets of the Appalachian mountains. John C. Campbell’s book The Southern Highlander and His Homeland, published in 1921, two years after his death, is considered a classic on the region.

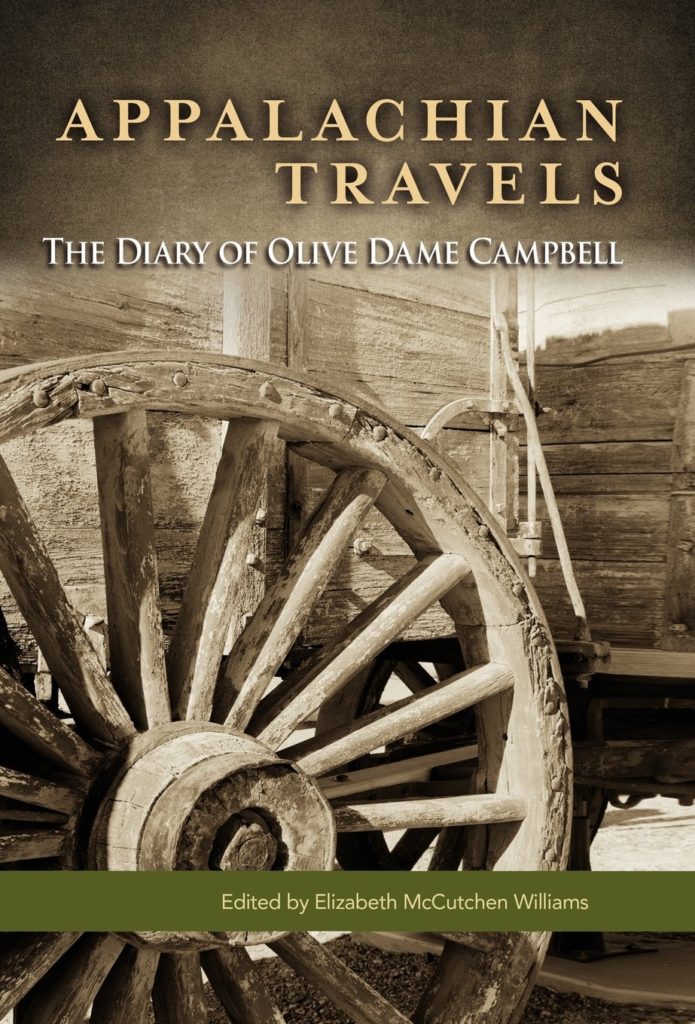

“Appalachian Travels: The Diary of Olive Dame Campbell.” Edited by Elizabeth McCutchen Williams. [81HCsaqpZsL.jpg]

As John C. Campbell researched the educational, social and economic conditions of the people of this remote region, Olive Dame Campbell busily collected information on the region’s rich cultural life — the mountain ballads, songs, and stories, and she noted that the English and Anglo-Saxon legacy still remained in many of the mountain communities in North Carolina, Tennessee, and Kentucky. The travel of the two was recorded in Olive Dame’s diaries recently gathered in Appalachian Travels: the Diaries of Olive Dame Campbell, edited by Elizabeth McCutchen Williams and published by the University of Kentucky Press (2012). When Olive Dame Campbell heard in 1915 that the noted folklorist Cecil Sharp was lecturing in America she arranged a trip to visit with him. She met him in Lincoln, Massachusetts in the home of a mutual friend, Mrs. James Storrow, a philanthropist and supporter of the Folk Life movement. In their meeting, Olive Dame Campbell plied her with examples of her ballads and song collecting which included ample notation of the tunes. While Sharp had come to America to promote English folk dancing, this meeting was pivotal for him. He saw an opportunity to expand his ballad and song collections. Sharp, after examining her work, needed little encouragement to dig deeper. Her trip was productive and Cecil Sharp, re-energized, left for Asheville, North Carolina, at the invitation of the Campbells, with Maud at his side.

Children dancing at Pine Mountain Settlement School, c. 1916. [melv_ii_album_320x_alt]

Convinced by Olive Dame and John C. Campbell that the best way to collect music in the region was to live among the people, Sharp soon took up residence in Hot Springs, in Madison County North Carolina not far from Asheville and from the small community of Brasstown where Olive Dame Campbell was to later found the John C. Campbell Folk School in 1925. Spurred on by Campbell’s tantalizing collection, Sharp and his assistant started a long journey in the mountains of Appalachia that covered much of the territory that the Campbells had explored in the early years of the 1900s. Their journey brought them to Pine Mountain in the Fall of 1917 during the third American trip of Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles. The Campbells were close friends of Katherine Pettit and Ethel de Long, and they were the conduit that directed Sharp and his assistant to Pine Mountain. On-site for five days, the team found the remote settlement school and its surrounding region to be one of the most productive episodes of their collecting.

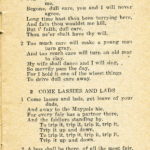

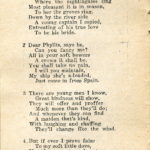

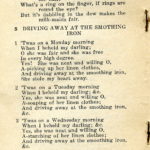

One outcome of the 1917 visit was the publication of the small booklet, “Folk Songs, Chanteys and Singing Games,” edited by Charles H. Farnsworth and Cecil J. Sharp and published by the Pine Mountain Settlement School print shop. [See GALLERY below.]

— Helen Wykle

SEE ALSO:

ABBY WINCH CHRISTENSEN Staff Biography (English Country Dance Instructor)

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH: SHEEP SHEARING AND CECIL SHARP (blog)

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH ENGLISH COUNTRY DANCE AT PMSS (Photograph gallery)

DOROTHY BOLLES Biography

DOROTHY BOLLES CORRESPONDENCE GUIDE 1925-1935

DOROTHY BOLLES CORRESPONDENCE I 1925-1930

DOROTHY BOLLES CORRESPONDENCE II 1931-1935

JAMES GREENE ACCOUNT OF CECIL SHARP AND MAUDE KARPELES AT PINE MOUNTAIN SETTLEMENT SCHOOL

MAY GADD Biography (English Country Dance Instructor)

PETER ROGERS ACCOUNT OF CECIL SHARP AND MAUDE KARPELES AT PINE MOUNTAIN SETTLEMENT SCHOOL

GALLERY: Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles Visit to PMSS

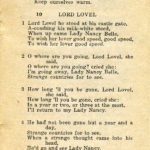

“Folk Songs, Chanteys and Singing Games,” edited by Charles H. Farnsworth and Cecil J. Sharp and published by the Pine Mountain Settlement School print shop.

- Cecil Sharp and Chas. Farnsworth. FOLK SONGS. {sharp0002.jpg]

- Cecil Sharp and Chas. Farnsworth. FOLK SONGS. [sharp0004.jpg]

- Cecil Sharp and Chas. Farnsworth. FOLK SONGS. [sharp0005.jpg]

- Cecil Sharp and Chas. Farnsworth. FOLK SONGS. [sharp0006.jpg]

- Cecil Sharp and Chas. Farnsworth. FOLK SONGS. [sharp0007.jpg]

- Cecil Sharp and Chas. Farnsworth. FOLK SONGS. [sharp0008.jpg]

- Cecil Sharp and Chas. Farnsworth. FOLK SONGS. [sharp0009.jpg]

- Cecil Sharp and Chas. Farnsworth. FOLK SONGS. [sharp0010.jpg]

- Cecil Sharp and Chas. Farnsworth. FOLK SONGS. [sharp0011.jpg]

- Cecil Sharp and Chas. Farnsworth. FOLK SONGS. [sharp0003.jpg]

Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles Visit to PMSS:

MARY NEAL AND MAUD KARPELES

Mary Neal (1860-1944). Wikipedia. [Mary_Neal_1860-1944.jpg]

Maud Karpeles, the second of Cecil Sharp’s collaborators, was the ideal choice for Sharp’s project in America and at Pine Mountain and apparently a more amicable traveling companion. His first English-born transcription collaborator, Mary Neal, left Sharp after only a short association and joined the growing English Suffrage Movement. To some that might signal her discontent with the curmudgeon Sharp, but there is scarce comment on Sharp’s side about discontent. Though Georgina Boyes in her book The Imagined Village: Culture, Ideology and the English Folk Revival, (1993) seems to think otherwise and bases her views on the earlier work of Roy Judge who sees the argument of the two surrounding the issues of approach to the folk revival. He says of the two that

Mary Neal and Cecil Sharp stood for two opposing approaches to the folk revival; Power or Accuracy, Content or Form, Philanthropist or Pedant, the terms may be varied, but the tension between them is clear, and it continues to exist today. Potentially it can produce a fruitful interaction with both elements present in a proper balance and in their best work both Sharp and Neal did successfully come to encourage that unity.

Nick Wall, Librarian at the Vaughan Williams Memorial Library and English Folk Dance and Song Society in London, suggests that Sharp and Neal “…fell out in a spectacular fashion.” He elaborates

Mary Neal wanted to get some folk dances for the children in the Esperance club to use and approached Cecil Sharp for help. Together they noted dances from William Kimber when he traveloled to the Esperance headquarters in London. This is where Cecil Sharp would have learnt to notate folk dance (with the help of Esperance teacher Florrie Warren, while Herbert Macilwaine noted the music).

Contrary to what seems obvious, Sharp was no newcomer to Suffrage. His sister Helen Sharp was an avid and forceful voice for Suffrage in England and after the death of their mother, she risked arrest and was not disappointed. Once, it is recorded she was physically manhandled and thrown out of a police precinct station for her disturbances. It is likely that her brother urged her on. Maud, obviously a suffragist but not one who actively joined the movement, became a lifelong assistant to Sharp and brought to his project a wealth of interest and talent.

By the time of Sharp’s death in 1924, Maud Karpeles contributions to the history of English folk dance and music was equal in many ways to that of her mentor. Following the death of Sharp, she became the protector and promoter of his legacy. Her careful work with regard to dance forms has often been ignored as her ballad transcription and recording are more often foregrounded. Her skills as a folklorist and her observations of dance in the Southern Appalachians were, however, remarkable, and they became foundational to later Appalachian dance research as noted in recent reviews of her work.

Born in 1885 of Jewish parents, Maud Karpeles became acquainted with Sharp following her association with the English settlement house called Mansfield House where she worked as a volunteer with the Invalid Children’s Aid Association. It was a project to directly assist disabled children in East Ham and Barking. She and her sister also volunteered with the Mansfield House Guild of Play that was founded by the Bermondsey University Settlement. It was also a program aimed at children. The idea was to “restore “the art of wholesome play” in the lives of children living in extreme poverty. [See Canning Town Folk.] Both sisters were familiar with the ethos of the settlement movement.

On an outing to Stratford on Avon the two Karpeles sisters learned of a folk dance competition taking place nearby. Cecil Sharp and Mary Neal, his first assistant, were judging the competition. After watching the folk dance demonstrations, both Maud and her sister were captivated and could see the benefits of dance on their current work at the settlement house. Later, when Sharp founded a folk dance school at Chelsea Training School, near their home, the two began lessons with Sharp. It was the beginning of a long mutual admiration. Sharp soon invited the sisters to teach folk dancing at the Chelsea school and the associations grew in stature and in numbers until the like-minded group formed the English Folk Dance Society that counted among its musicians and artists such men as Vaughan Williams, Perceval Lucas, G.J. Wilkinson and George Butterworth. These illustrious members, however, did not always prove to be loyal supporters and friends of women and Maud later encountered conflicts with the Society regarding intellectual property rights in the Sharp estate and possibly antisemitism as the world moved to war. The most acrimonious debate she faced was her staunch belief that women should be allowed to engage Morris and Sword dancing and that it not be relegated only to men. Her adamant position may have cost her advancement in the Society, but she found other means to continue her love and promotion of dance and her humanitarian work. Ultimately she was one of the founding members of the International folk movement and a founding member of the International Folk Music Council. She died in 1976 at the age of 91.

Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles Visit to PMSS: CRITICISM

The work of Cecil Sharp and Maude Karpeles is not without its sharp critics. The argument between C. J. Bearman and Dave Harker is well known to Sharp scholars. Bearman once caustically remarked on Harker that, “…To question the opinion of a Trotskyist about Sharp and his work is rather like taking one’s view of the Communist Manifesto from a member of the British National Party,” Bearman’s criticism of Harker seems largely focused on Harker’s political leanings and not on his collective wisdom regarding folklore. Harker’s book Fakesong (1984) focuses his arguments against Sharp and against Bearman and has found sympathy with some scholars of the Southern Appalachians, particularly those of a postmodern bent or, as Bearman characterizes them, “… prominent left-wing historians.”

Nick Wall, at the Vaugh Williams Memorial Library and English Folk Dance and Song Society, weighs in on the clash of these two Sharp scholars and adds additional insight into the cultural argument

The Harker-Bearman clashes (and other similar stuff) is quite complex. Harker has been heavily criticized for statistical inaccuracies in his analysis and also for a kind of cartoon Marxism — there is clearly something very interesting going on with middle and upper-class people taking an interest in folk culture, but Sharp was certainly not in it for the money — his Appalachian diaries show the efforts that he had to make to raise funds for his song collecting. On the other side of the argument, while Bearman’s research is often good, he lets his anger distort his analysis of the research. Over here [England] Cecil Sharp would now be seen as someone who did great work but who was a great romantic (believing folk song and dance to be older and more essentially rural than it was. Like nearly all the other collectors, he had a dislike of popular culture and tended to overlook the interaction between popular culture and folk culture. [Nick Wall, Correspondence, 2019-03-05]

Some of the historians that Bearman cites have earned the ire of many Appalachian scholars, but one, David Whisnant is not nearly so caustic as Bearman suggests and fairly points to Sharp’s confused interest in Appalachian blacks and their music and life. Whisnant, in All That is Native and Fine: The Politics of Culture in an American Region (1983), in fact, says of the collaboration of Cecil Sharp with Olive Dame Campbell

How does the collaboration of Olive Dame Campbell and Cecil Sharp look after more than a half-century? In the narrowest of terms –the quantity and quality of the preferred material they assembled and the skill of its presentation –their work remains a landmark in the history of an enterprise that witnessed more than its share of greed, pettiness, and misrepresentation. [Whisnant,p.125]

And, then, Whisnant goes on to criticize Henry D. Shapiro’s characterization of Cecil Sharp in Shapiro’s much lauded Appalachia On Our Mind: The Southern Mountains and Mountaineers in the American Consciousness, 1870-1920 (1978), noting that Shapiro depicts Sharp as “…a culturally and politically naive, self-aggrandizing promoter of myths of Merrie Olde England and ‘the inherent value of the naif culture of Appalachia.'” These criticisms clearly have more to do with the politics of cultural intervention, the rise of postmodern sensitivity to appropriation and probably some scholarly envy, than any substantive criticism of the work of Sharp and Karpeles. For example, Shapiro says

By accepting the otherness of Appalachia, and by providing Americans with a set of terms through which to understand both Appalachian otherness and the relationship of the mountaineers to the rest of the American population, Sharp not only established the peculiarities of mountain life as legitimate patterns in the present but also identified the mountaineers at once as a distinct people and as the conservators of the essential culture of America. And it was this, ultimately, which made his vision appropriate to contemporary conceptions of the nature of American civilization.

What is found deep within the many criticisms of criticisms is something of the ongoing debate surrounding “otherness” and now “American exceptionalism.” Many of the arguments still continue in recent books such as the strident White Trash: The 400-year Untold History of Class in America by Nancy Isenberg, which also wrestles with the culture of the Southern Appalachians. If Appalachia was created, as Shapiro and his reviewers suggest, on the observations of outsiders rather than the objective realities of mountain life, then we have in Cecil Sharp a unique opportunity to test a much-repeated thesis against a well-documented and documenting “outsider.” It is not surprising to see animated discussions of Sharp in so many histories of the Southern Appalachians.

What Harker and other critics often objected to was the seeming “appropriation ” and “exploitation” of Sharp and Karpeles of the “working class.” The criticism seems to place more emphasis on ongoing class debates that continue to surface in much of the scholarship on Appalachia, particularly of late. Probably the most extreme criticism of Harker is his accusation that Sharp literally invented English folk song rather than collecting it.

Another critic, Georgina Boyes also roundly criticizes Sharp in her book The Imagined Village – Culture, ideology and the English Folk Revival in an argument that generally follows that of Harker but breaks new ground in her discussions of “Folk” as “other.” It is interesting that in a review of Boyes’ book by Vic Gammon for Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, [ Vol.26, No.2 (Summer, 1994), pp.390-392] he says in the conclusion of his review, “The historian must cultivate empathy as well as critical engagement if she is to guard against contributing to the enormous condescension of posterity.” While Gammon’s observations are centered on Boyes, he might have allowed that “empathy and critical engagement” have obviously struggled to maintain a high-road in both gender camps throughout discussions of the work of Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles.

************

** We are especially grateful for the close scrutiny given this commentary by David Millstone, Norwich, Vermont, dance historian and author of the blog DAVID MILLSTONE DANCE and currently President of the Country Dance and Song Society of America. His dedication and that of others to the art of folk dance keep this art form joyfully engaged with many communities across the country.

Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles Visit to PMSS: BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bearman, C.J. “Cecil Sharp in Somerset: some reflections on the work of David Harker.” Folklore 113: 1 (Apr., 2002): 11–34.

Boyes, Georgina.The Imagined Village: Culture, Ideology and the English Folk Revival, Manchester: Manchester University Press ; distributed by St. Martin’s Press, New York, NY, 1993. [Boyes, Georgina (2010). The Imagined Village: Culture, ideology and the English Folk Revival. London: No Masters Cooperative Limited. ISBN 978-0-9566227-0-9.]

Bronson, Bertrand Harris. The Traditional Tunes of the Child Ballads: With Their Texts, According to the Extant Records of Great Britain and North America, four volumes (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1959-72. Northfield, Minnesota: Loomis House Press,

Canning Town Folk 3 – “Maud Karpeles and the Birth of the English Folk Dance Society” http://www.ju90.co.uk/ctfolk/ctfolk3.htm

A video tribute to Cecil Sharp mentions the Far House and “Kentucky Running Set” seen by Sharp and Karpeles at Pine Mountain. “Canning Town” also contains a small selection of films taken from Kinora Spools Made in 1912 with Cecil Sharp, Maud Karpeles and others, dancing.

“Cecil Sharp in America, 1999”. Mustrad.org.uk. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

Child, Francis James . Child Ballads, [Wikipedia] Accessed, 2016-09-20.

Clayre, Alasdair. Nature and Industrialization: An Anthology. Oxford: Oxford University Press in association with the Open University Press, 1977. Print.

“Enthusiasm’s” No. 36, “Jumping to Conclusions, Mike Yates examines a row that is bubbling away beneath the surface of British folk song scholarship”. Mustrad.org.uk. Retrieved 2010-01-31.

Filene, Benjamine. Romancing the Folk: Public Memory & American Roots Music, Chapel HIll: University of North Carolina Press, 2000

Gammon, Vic. Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies, Vol 26, No. 2 (Suummer, 1994), pp. 390-394 [Review of Georgina Boyes.The Imagined Village: Culture, Ideology and the English Folk Revival,]

Howes, Frank. “Cecil Sharp.” The Musical Times. 109.1499 (1968): 38-39. Print.

Jamison, Philip. Southern Appalachian Hoedowns, Reels, and Frolics: Roots and Branches of Appalachian Dance, Champaign, IL: University of Illinois Press,2015.

Karpeles, Maud. and Strangways, A.H. Fox. Cecil Sharp: His Life and Work. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967. Print. See also Dillon Bustin, Folklore Forum, “The Morrow’s Uprising: William Morris and the English Folk Revival” Folklore Forum 15 (1982) 17–38

Keller, Kate V. W, and Genevieve Shimer. The Playford Ball: 103 Early Country Dances, 1651-1820 : As Interpreted by Cecil Sharp and His Followers. Pennington, NJ: A Cappella Books, 1990. Print. {WorldCat to see various editions.]

Reeves, James, and Cecil J. Sharp. The Idiom of the People: Engl. Traditional Verse from the MSS of Cecil Sharp. London: Heinemann, 1958. Print.

Shapiro, Henry D. Appalachia on Our Mind: The Southern Mountains and Mountaineers in the American Consciousness, 1870-1920. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1978.

Sharp, Cecil J, and James Reeves. The Idiom of the People: English Traditional Verse. London: Heinemann, 1958. Print.

Sharp, Cecil J, and Herbert C. MacIlwaine. The Morris Book: With a Description of Dances As Performed by the Morris-Men of England. Parts 1, 2 & 3. Wakefield: EP Publishing, 1974. Print.

Sharp, Cecil J. Folk Songs of English Origin Collected in the Appalachian Mountains: First and Second Series. London: Novello, 1966. Print.

Sharp, Cecil J. Country Dance Tunes. London: Novello, 1923. Print.

Sharp, Cecil J, George Butterworth, and Maud Karpeles. The Country Dance Book. London: Novello and Company, Ltd, 1909. Print.

Sharp, Cecil J. Cecil Sharp House: The Story of Twenty-One Years 1930-1951. London, 1951. Print.

Sharp, Cecil J, and Charles H. Farnsworth. Folk-songs, Chanteys and Singing Games. New York: H.W. Grey, 1909. Print.

Sharp, Cecil J, and Imogen Holst. Twelve Songs for Children from the Appalachian Mountains. London: Oxford University Press, 1937. Musical score.

Sharp, Cecil J, Maud Karpeles, and Benjamin Britten. Eighty English Folk Songs from the Southern Appalachians. Cambridge, Mass: M.I.T. Press, 1968. Musical score.

Sharp, Cecil J, and James W. Raine. Mountain Ballads for Social Singing. Berea, Ky: Berea College Press, 1923. Print.

Sharp, Cecil J, Harley Granville-Barker, and William Shakespeare. The Songs & Incidental Music Arranged & Composed by C.j. Sharp for Granville Barker’s Production of a Midsummer Night’s Dream at the Savoy Theatre in January 1914, [with Introduction]. Pp. 31. Simpkin, Marshall & Co: London; Barnicott & Pearce: Taunton, 1914. Print.

Sharp, Cecil J, George Butterworth, and Maud Karpeles. The Country Dance Book. London: Novello and Company, ltd, 1909. Print.

Scherman, Tony. ” A Man Who Mined Musical Gold in the Southern Hills.” 1985, Smithsonian, volume 16, issue 1, p.173-

Strangways, Arthur H. F, Maud Karpeles, and Cecil Sharp. Cecil Sharp. London: Milford, 1933. Print.

Szczelkun, Stefan. The Conspiracy of Good Taste: William Morris, Cecil Sharp, Clough Williams-Ellis and the Repression of Working Class Culture in the 20th Century. London: Working Press, 1993. Print.

Wells, Evelyn K. The Ballad Tree: A Study of British and American Ballads, Their Folklore, Verse and Music, Together with Sixty Traditional Ballads and Their Tunes. New York: Ronald Press Co, 1950. Print.

Whisnant, David E. All That is Native and Fine: The Politics of Culture in an American Region, (Twenty-fifth Anniversary Edition), Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983 (2009).

Williams, Elizabeth McCutchen, ed. Appalachian Travels: The Diary of Olive Dame Campbell, Lexington: University of KY Press, 2012.

SEE ALSO:

VISITORS Guide to Consultants, Guests, and Friends of PMSS

LORAINE WYMAN and HOWARD BROCKWAY Visitors Biography

PERCY MACKAYE Visitor Biography

|

Title |

Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles Visit to PMSS |

|

Identifier |

CECIL SHARP AND MAUD KARPELES VISIT TO PMSS |

|

Creator |

Pine Mountain Settlement School, Pine Mountain, KY |

|

Alt. Creators |

Ann Angel Eberhardt ; Helen Hayes Wykle ; |

|

Subject Keyword |

Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles Visit to PMSS ; Pine Mountain Settlement School ; Cecil J. Sharp ; Maud Karpeles ; dance ; Kentucky Running Set ; music ; ballads ; Far House I ; Far House II ; Ethel de Long ; Ethel de Long Zande ; Katherine Pettit ; American Folk Dance Society ; English Folk Dance Society ; folk dancing ; John C. Campbell ; Olive Dame Campbell ; Russell Sage Foundation ; Council of the Southern Mountains ; Mary Neal ; transcribers ; English Suffrage Movement ; Helen Sharp ; suffragists ; folklorists ; settlement houses ; criticism ; Pine Mountain, KY ; Harlan County, KY ; Southern Appalachia ; Asheville, NC ; Lincoln, MA ; Hot Springs, NC ; London, England ; |

|

Subject LCSH |

Sharp, Cecil J., — 22 November 1859 – 23 June 1924. |

|

Date |

2016-08-22 |

|

Publisher |

Pine Mountain Settlement School, Pine Mountain, KY |

|

Contributor |

n/a |

|

Type |

Collections ; text ; image ; |

|

Format |

Original and copies of documents and correspondence in file folders in filing cabinet |

|

Source |

Series 30: Music and Dance ; Series 22: CONSULTANTS, FRIENDS, COMMUNITY, GUESTS AND VISITORS Related to Pine Mountain Settlement School |

|

Language |

English |

|

Relation |

Is related to: Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections, Series 30: Music and Dance ; Series 22: CONSULTANTS, FRIENDS, COMMUNITY, GUESTS AND VISITORS Related to Pine Mountain Settlement School |

|

Coverage Temporal |

1859 – 1976 |

|

Coverage Spatial |

Pine Mountain, KY ; Harlan County, KY ; Southern Appalachia ; Asheville, NC ; Lincoln, MA ; Hot Springs, NC ; London, England ; |

|

Rights |

Any display, publication, or public use must credit the Pine Mountain Settlement School. Copyright retained by the creators of certain items in the collection, or their descendants, as stipulated by United States copyright law. |

|

Donor |

n/a |

|

Description |

Core documents, correspondence, writings, and administrative papers of Cecil J. Sharp and Maud Karpeles ; clippings, photographs, books by or about Cecil J. Sharp and Maud Karpeles ; |

|

Acquisition |

n/d |

|

Citation |

“[Identification of Item],” [Collection Name] [Series Number, if applicable]. Pine Mountain Settlement School Institutional Papers. Pine Mountain Settlement School, Pine Mountain, KY. |

|

Processed By |

Helen Hayes Wykle ; Ann Angel Eberhardt ; |

|

Last Updated |

2016-10-09 hhw ; 2017-10-01 hhw ; 2022-03-17 aae per corrections by Jamie Greene ; 2022-09-13 hhw ; |

|

Bibliography |

[SEE BIBLIOGRAPHY AT END OF NARRATIVE ABOVE] |