Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 30: MUSIC AND DANCE

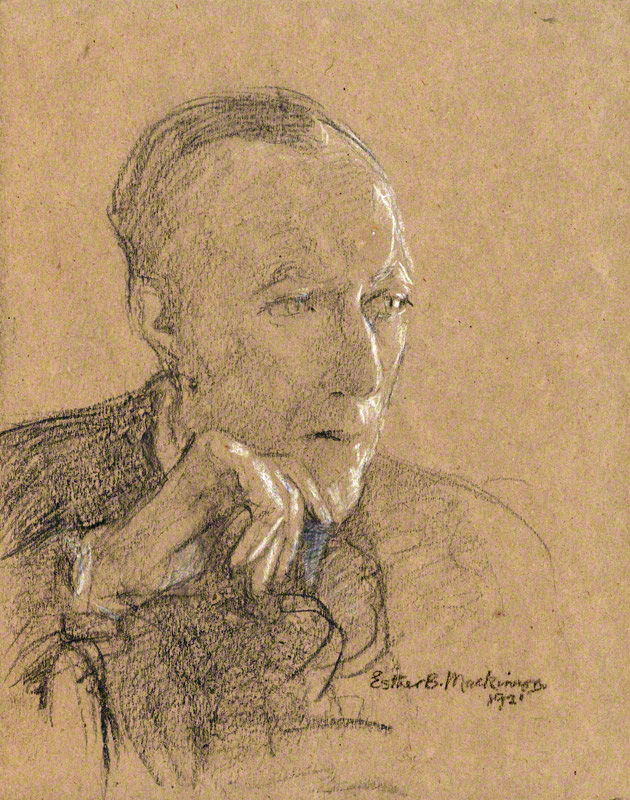

Cecil Sharp by Esther Blaikie MacKinnon, chalk, 1921. NPG 2517 National Portrait Gallery, St. Martin’s Place, London. See below: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ [mw05729.jpg]

TAGS: Peter Rogers Account of Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles Visit to PMSS, Peter Rogers, Cecil J. Sharp, Maud Karpeles, dance, Kentucky Running Set, May Day, music, ballads, Far House I, Far House II, Ethel de Long, Ethel de Long Zande, Katherine Pettit, Marguerite Butler, May Ritchie Deschamps, Leon Deschamps, Evelyn K. Wells, American Folk Dance Society, English Folk Dance Society, Helen Storrow , Boston Center, Pine Woods, MA, folk dancing, Morris Dance, Sword Dances, Emily Hill Creech, Bertha Sizemore, Maud Baker, Maggie Baker, Burchel Wooten, Chester Wooten, Lauren Ritchie, Pearl Blanton, Stella Blanton, Nora Howard, Clara Siler, Esther B. MacKinnon, Farm House, Berea Country Dance School, Berea College, Alonzo Turner, John Turner, Creed Turner, James Greene

PETER ROGERS ACCOUNT of Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles Visit to PMSS

Peter Rogers was born and grew up at Pine Mountain Settlement School. He is the son of Burton Rogers, staff member and former Director of Pine Mountain Settlement School from 1947 to 1983 and Mary Rogers, staff, librarian, environmentalist, and folk dance teacher.

Peter followed in his mother’s footsteps as a Country Dance caller and historian and lives in Frankfort, Kentucky. He prepared this excellent account of the Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles visit for the dedication of Far House II in 1997. It was updated in 2000 and here it is again, updated for the special memorial celebration of Cecil Sharp and Maude Karples’ visit to Pine Mountain. The celebration at the School includes a traveling exhibition of photographs of the noted folklorist and his work as a gatherer of English Country Dancing and of Appalachian Mountain balladry and a weekend of dance and music.

Peter Rogers’ thorough account provides information not found in his earlier commentary prepared for Robin Lambert, PMSS Director in 1997, along with that of James Greene III. It adds additional reflection on the history of the Cecil Sharp event at the School. We are grateful for his insights, his added details, and for sharing his work with this online archive.

His commentary joins that of Jamie Greene, a member of the PMSS Board of Trustees who also prepared remarks for the dedication of Far House II in 1997, and the later exploration by the Editors of this website, Helen Wykle and Ann Angel Eberhardt.

PETER ROGERS ACCOUNT of Cecil Sharp and Maud Karpeles Visit to PMSS

By Peter Rogers, 9/28/2017

Cecil Sharp sees students “running a set”

on the stone terrace of Far House

at Pine Mountain Settlement School

the evening of August 31, 1917. [1]

Cecil Sharp was an English musicologist who was instrumental, along with several prominent colleagues in the British music community (e.g. Vaughan Williams, Grainger, Butterworth) in the re-discovery, collection and revival of English folk song, music and dance in the decades around the turn of the twentieth century. He was instrumental in both the English Folk Song Society and the English Folk Dance Society (later merged into the English Folk Dance and Song Society). In 1915, he traveled to America to lecture and to instruct groups in the performance of English folk dance and song.

Olive Dame Campbell accompanied her husband John C Campbell in his field trips through the Southern Appalachian mountains doing research for the Russell Sage Foundation resulting in the book, The Southern Highlander and His Homeland. In 1908, while they were visiting Hindman Settlement School, HSS co-founder Katherine Pettit introduced Mrs. Campbell to the local ballads she had collected. Mrs. Campbell was so enchanted with them that she started collecting also, particularly around her home in Asheville, NC. In 1915, when she heard Cecil Sharp was visiting her friend Mrs. James Storrow in Lincoln, Massachusetts, she went to meet him there. She took her ballad collection for Sharp’s inspection and encouraged him to come to the mountains and do a proper job of notating. He was thrilled to see songs that were obviously of English origins so well preserved in the remote parts of America and decided to take on the challenge. Over the next several years, he and his assistant, Maud Karpeles, made several collecting trips through the Southern mountains.

In late August 1917, they spent a week at Pine Mountain collecting songs from the students and neighbors in the community. They collected songs during the day and after supper they sang songs for and with the students and staff. They also taught several Playford dances[2] to the Pine Mountain staff. Evelyn K. Wells, School secretary, recalled:

There were the two noon hours when eight workers from the staff learned ‘Rufty Tufty’, ‘The Black Nag’ and ‘Gathering Peascods’ on the porch of Laurel House to Mr. Sharp’s teaching and Miss Karpeles’ singing of the tune. … All the work of the day stopped during those lessons — children stopped weeding the vegetable gardens, girls stopped washing the clothes, even the workmen stopped building the school-house. And this was in the days when we worked incessantly to put roofs over our heads and to can food against the winter, and every minute counted.[3]

In the 1930s, Miss Wells returned to Wellesley College in the English Department where she compiled her book The Ballad Tree. She also served on the Advisory Board of CDSS.

Cecil Sharp was very impressed with Pine Mountain. In a letter to Olive Dame Campbell right after his visit, he wrote:

There is a mountain-school – if you can call it a school – after my own heart! It is just a lovely place, fine buildings, beautiful situation, and wisely administered. Miss Pettit and Miss de Long are cultivated gentlefolk, who fully realize the fine innate qualities of the mountain children and handle them accordingly. And the children, many of them little more than babies, are just fascinating, clean, bright, well-behaved little things, who come up, put their hands in yours, and behave like the children of gentle-folk – which is, of course, just what they are. This settlement is a model of what the mountain-school should be. Everything is beautiful…. Flowers are grown everywhere and large bowls of them in every room. They do not emphasize the school side of things, nor, I am glad to say, the church side. They sing ballads after dinner and grace before it.[4]

Sharp’s diary entry for Friday, 31 August 1917, says:

After breakfast Miss de Long and I have a long talk. I should dearly like to help them here with folk songs & dances as I am greatly enamoured with the way in which things are conducted here. I expected to find Miss de Long a very precious, Arty & Crafty sort of person but she really isn’t, while Miss Pettit is a really capable, energetic person of wide vision – just the sort of person for this job. They pay considerable attention to the aesthetic side of things. The houses are well & picturesquely planned, flowers are everywhere and the children dressed very simply but quite nicely & prettily. It is a lovely spot, this valley and there is no doubt but that a great work is being done here, well & nicely too. In the evening we go to Miss de Longs and see a Running Set. This must be carefully noted some day. It is a fine dance and may serve to throw light on some of the older 17th and 18th cent[ury] dances.[5]

One of the students, May Ritchie (Deschamps), recalled singing and running the sets for him:

… Mr. Sharp stayed at Farm House with Mr. Zande. As I remember going to that house to sing for him my version of Pretty Polly, Sourwood Mountain, John Riley, Jackarow, etc.

Their evenings were spent on the porch where he discussed ballads & dances of the Old English kind and he was a very interesting person & so full of enthusiasm about publishing his ballad books. When Jean, my sister, was making a study in England she found my name mentioned in one of his books.

One evening Miss de Long invited our best set running people to come to Far House to run sets for Mr. Sharp. He was quite surprised and very delighted. We did them on the front porch as I can remember Mr. Sharp sitting in the door to the living room looking out on us as we ran the set for him. … we had only some one clapping hands & no music.[6] It was a beautiful moon light night and only dim oil lamps burning in the living room, – that was before we got electricity.

He raved & raved over the dances and thanked us all many times for a wonderful delightful evening.

In those days we never spoke of them as dances – always the running of sets. I wish I could name all the people who ran the sets that night. Emily Hill Creech – Bertha Sizemore, Maud and Maggie Baker from Wooten Creek. Burchel & Chester Wooten to name a few. Lauren Ritchie, Pearl Blanton, her sister Stella. Nora Howard maybe. Clara Siler….[7]

Marguerite Butler was a teacher and extension worker at Pine Mountain at the time. She later left Pine Mountain to help Olive Dame Campbell start the John C Campbell Folk School in Brasstown, NC. There she married the Danish farmer, Georg Bidstrup, who later became the Director of the Folk School. In 1972 she related her memories of that night in an oral history interview:

Now, I was fortunate enough to have been at Pine Mountain when Cecil Sharp and Maude Karpeles crossed over the mountain one day … Cecil Sharp of course is the great English authority on the folk song and the folk dance. And he hadn’t seen the running set anyplace. He had been collecting folk songs for a number of months in this country in some of the mountain states and also in the east. He had been told by various church schools and various individuals he wouldn’t be interested in it, it was uncouth, it was vulgar. But to his surprise one night, a dance was planned … on the terrace at the back of Far House ….

[The dancers] were all the people who had been born and raised and lived in that part of the country. And they went through the figures and did the running set for Cecil Sharp. I never saw anyone more excited…. And he knew right off that he had found something older than anything he had known in England. Now Cecil Sharp later saw this dance done in several other places in Kentucky and other places it was always done four couples in a square. But he himself wrote that no place was it done in the same form and as beautiful a form as it was at the Pine Mountain School.

… [Several years] Later Mrs. [James J.] Storrow came down to visit, and Mrs. Storrow was president of the Girl Scouts at one time, and [also] owned the camp [Pinewoods] where the Country Dance Society held their annual camp, their training course. Mrs. Storrow taught us a number of dances; the only one I can remember now was Hunsdon House. [8]

As noted above, Sharp had been informed that there was a rough form of dancing in the areas he was collecting in, but that it wasn’t worthy of his interest. So even after he had shared his work collecting several dance forms in England, and had taught 3 English dances to the staff, they couldn’t interest him in the local dance form they had adopted as an important feature of the school’s program. Evelyn Wells’ letter suggests how the staff arranged things to get his attention:

There was the warm, rainy night when in front of the fireplace at the Far House we listened to his talk of Appalachian discoveries, and watched with a bit of amusement how he lost the thread of his talk as he became conscious of a rhythmic patting and stamping on the porch and suddenly stopped, and with a look at Miss Karpeles stepped outside, followed by her. His own description of that first Running Set is in his book, but I remember watching those two closely, for we had tried hard to interest him by our accounts, and he had shown little response. Out came a notebook, in which he jotted without taking his eyes from the dancers, there were whispered remarks between him and Miss Karpeles, and in the first pause in the dancing, questions asked of the caller, or top man. From then on, of course, he was hot on the trail and we gave him every scent we could. [9]

Cecil Sharp was excited by what he had witnessed, both academically and emotionally. Even before he returned to England, he published his description of the dances they saw in Kentucky and dedicated it to the Pine Mountain Settlement School. In the Introduction, he describes the evening and his impressions and conclusions.

In the course of our travels in the Southern Appalachian Mountains in search of traditional songs and ballads, we had often heard of a dance … but, as our informants had invariably led us to believe that it was a rough, uncouth dance … we had made no special effort to see it. When at last we did see it performed at one of the social gatherings at Pine Mountain Settlement School it made a profound impression upon us. We realized at once that we had stumbled upon a most interesting form of the English County-dance which, so far as we knew, had not been hitherto recorded, and a dance, moreover, of great aesthetic value. On that occasion, the dance was sprung unexpectedly upon us by Miss Ethel de Long, and, being quite unprepared, we were unable to make any attempt to note it.

… we may with some assurance claim: –that it is the sole survival of a type of Country-dance which, in order of development, preceded the Playford dance, that it flourished in other parts of England and Scotland a long while after it had fallen into desuetude in the South, and that some time in the eighteenth century it was brought by emigrants from the Border counties to America where it has since been traditionally preserved.

… [When] I had penetrated into the Southern Appalachians and found the old Puritan dislike, fear, and distrust of dancing expressed in almost every log-cabin I entered … [imagine] my surprise … when, without warning, the Running Set was presented to me, under conditions, too, which immensely heightened its effect. It was danced one evening after dark, on the porch of one of the largest houses of the Pine Mountain School, with only one dim lantern to light up the scene. But the moon streamed fitfully in lighting up the mountain peaks in the background and, casting its mysterious light over the proceedings, seemed to exaggerate the wildness and break-neck speed of the dancers as they whirled through the mazes of the dance. There was no music,[6] only the stampings and clappings of the onlookers, but when one of the emotional crises of the dance was reached – and this happened several times during the performance – the air seemed literally to pulsate with the rhythm of the “patters” and the tramp of the dancers’ feet, while, over and above it all, penetrating through the din, floated the even, falsetto tones of the Caller, calmly and unexcitedly reciting his directions.

The scene was one which I shall not readily forget … [10]

As well as suspecting a direct link to earlier-than-Playford dances, he [Sharp] also noted apparent connections to games and to ritual dances.[11] Seeing this dance form also helped him interpret some of the Playford dances that he had previously been unable to visualize.

Sharp urged Pine Mountain to continue to incorporate the student’s own heritage of songs, dances, crafts, etc. into the program, but to also expand to include the traditions of their ancestors from the British Isles. From then on, the School has continued to include the English folk songs and dances right along side those that had been preserved in the area as a living tradition. Over the next couple of decades, leaders from the American Center of EFDS in Boston (later to become the Country Dance and Song Society of America) visited Pine Mountain often and broadened the scope to include Morris and Sword dancing, Mummers Plays, and May Day celebrations.

Pine Mountain introduced these traditions to other related schools in the region. These institutions, through their Council of Southern Mountain Workers, then created a recreation extension program to help promote folk recreation throughout the region. This program was later continued by Berea College who then started the Christmas Country Dance School to help train leaders and the Berea College Country Dancers to help demonstrate and promote folk traditions and dance.

Meanwhile, Sharp started immediately to share what he called the “Running Set”[12] with other groups even before he got home to England. From his efforts, the dance has been enjoyed all across America, and England, and the world. It has become recognized not only as a descendant of some lost form of English / Scottish / Irish / ??? dance, but also as a direct ancestor to the mid-western and western square dances.

NOTES:

[1] This account was compiled by Peter Rogers. The first version was in a letter written in 1997 for the new Director and first occupant of the re-built Far House which was dedicated September 27, 1997. It was revised and expanded for the October 6-8, 2017 Centennial Celebration of Cecil Sharp’s visit to Pine Mountain Settlement School.

[2] In the last several years before his visit, Sharp had been recreating 17th and 18th century “country dances” found in “The English Dancing Master” by John Playford (1651) and later editions. These are three he had recently interpreted.

[3] Quoted in “Cecil Sharp” by A. H. Fox Strangways and Maud Karpeles.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Sharp’s diary entry for Friday 31 August 1917. http://www.vwml.org/browse/browse-collections-sharp-diaries/browse-sharpdiary1917#recordnumber=249 retrieved September 29, 2016.

[6] Other informers in the community relate that they usually danced to the music of the banjo and/or fiddle, often with a beater who used two small sticks to beat the rhythm on the bottom string of either instrument. This was usually accompanied by the “patter” of the on-lookers. Sharp also noted this accompaniment in other communities. However, at the School they frequently danced to just the “patter” – perhaps for administrative reasons.

[7] Excerpts from a reply letter from May Ritchie Deschamps to Peter Rogers dated August 3, 1975.

[8] Interview with Marguerite Butler Bidstrup by Terry Thorp on January 21, 1972. Full audio and transcript available at Berea College, Hutchins Library, Appalachian Oral History Collection SAA 59. The PMSS portion of transcript is available on-line at https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=13993. Look to the full version for an interesting account of Olive Dame Campbell’s efforts that led to Sharp’s collection trips to the Southern mountains.

[9] Letter from Evelyn K. Wells to Maude Karples.

Quoted in “Cecil Sharp in America, collecting in the Appalachians” Michael Yates. 1999. http://www.mustrad.org.uk/articles/sharp.htm retrieved September 25, 2017.

[10] “The Country Dance Book, Part V, Containing the Running Set” (1918).

[11] Other scholars since have expressed differing opinions as to the origins of this dance form, but I’m not convinced that anyone yet has the full answer. There is strong evidence for an as yet unidentified common source including a distinct pool of figures for the circle square dances of the Southeastern United States.

[12] Most local people just referred to the dance as “running a set” — “running” as in “running an errand” and “set” meaning a group of figures. As a collector and promoter, Sharp needed to give the dance a name. He probably asked someone “What do you call this dance?” and got the reply “Oh, they’re just running a set” and so he just changed “running” to an adjective, thereby conveying another meaning.)

SEE ALSO:

CECIL SHARP AND MAUDE KARPELES Visit to PMSS

(By the Editors, Helen Wykle and Ann Angel Eberhardt)

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH: English Country Dancing at PMSS

(Includes Photo Gallery)

DOROTHY BOLLES Staff Biography

DOROTHY BOLLES CORRESPONDENCE GUIDE 1925-1935

DOROTHY BOLLES CORRESPONDENCE I 1925 -1930

DOROTHY BOLLES CORRESPONDENCE II 1931-1935

JAMES GREENE III ACCOUNT of the Visit of Cecil Sharp and Maude Karpeles at PMSS

MAY GADD Visitor Biography

LICENSE PERMISSION Letter

Esther B. MacKinnon. CECIL SHARP drawing – National Portrait Gallery, St. Martin’s Place, London, Creative Commons Licence Permission.

Please find, attached, a copy of the image, which I am happy to supply to you with permission to use solely according to your license, detailed at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/

It is essential that you ensure images are captioned and credited as they are on the Gallery’s own website (search/find each item by NPG number at http://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/advanced-search.php).

This has been supplied to you free of charge. I would be grateful if you would please consider making a donation at http://www.npg.org.uk/support/donation/general-donation.php in support of our work and the service we provide.

Regards

Rights and Images Department

National Portrait Gallery St Martin’s Place London WC2H OHE