Pine Mountain Settlement School

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH

Blog

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH Going and Coming Back I

A personal reflection on Appalachian migration.

“The effect of mass migration has been the creation of radically new types of human beings: people who root themselves in ideas rather than places, in memories as much as material things; people who have been obliged to define themselves — because they are defined by others — by their otherness; people in whose deepest selves strange fusions occur, unprecedented unions between what they were and where they find themselves.”

Salman Rushdie

“It seems to me from my personal experience that there is kindness everywhere in different proportions and more goodness and tenderheartedness than we read of in the moralists.”

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

These may seem strange companions in a discussion of migration — Salman Rushdie and Elizabeth Barrett Browning — yet they both share an understanding of our deeper selves. They reach into the core of what makes us human regardless of our origins. Migration can tear at that core in ways we are still coming to understand. In Appalachia migration is a constant theme that runs throughout our conversations. So is the idea that others can redefine us; it makes us defensive and not just because we are perceived as “something else.” It is much more complex.

My grandfather was always on the move, going and coming from somewhere else but always returning to there —to Appalachia. He didn’t have a car. He was left to the many devices of journeying. Neither did he have a career that kept him moving up the staircase of advancement in the ways we understand advancement today. He simply moved. That was his advancement. He changed his location and with it, he changed his sense of self. Though he mined coal for much of his life, we never knew many of the other jobs he worked into and out of in his goings. But we knew him because he was always coming back.

“Papaw,” the Appalachian term of endearment, or not, — for the fathers and grandfathers of children growing up in the mountains of eastern Kentucky, was always going and coming back. He kept the flow of life in the household unsteady, but he also kept it animated by expectation. When he returned, the household filled with somber but expected and at times unspoken conversations. Where did you go? What did you do? Who did you meet? What was it like living … there? Did you miss us? Silence. The silence in the house dictated by our grandmother Daisy, whom we affectionately called “Daa”, was palpable. Our questions and the non-answers often hung in the air with their weight of deep anxiety. But the silence was always temporary. When the house filled with family, with the sons, the wives, and their sons and daughters, the voices and laughter, stories filled the rooms. The memories of family, together, flowed like healing waters over all the unspoken answers to Papaw’s going and coming. Our Daa kept him in her wary view and could silence his answers with just a gaze. He had gone one too many times.

When we gathered, Daa often filled her table with fried chicken, cornbread, ham slices with red-eye gravy, fried oysters, pickles, mashed white potatoes from the garden, cole-slaw, and fried sweet potatoes — crisp with hard sugar edges. We playfully juggled for chicken legs, yearned for four-legged chickens, and made jokes about the “toot” which Daa always left on the bird. No one got enough sweet potatoes, and we rarely had room for the blackberry cobbler, but we ate it anyway. For us, coming home was a celebration of family and the wealth of the table. We, the family and the cousins, repeated this ritual many times in the early years of growing up. Our visits were frequent because we never lived far from our grandparents. We traveled to Coxton, a coal camp in Harlan County, Kentucky, where our grandparents spent most of their lives; first, as residents of the coal camp and later in a house they bought near the coal camp on the road to Evarts. Our coming and going was across the county of Harlan, or up and over Pine Mountain to the valley where my family lived, at Pine Mountain Settlement, a beautiful little community nestled between two steep mountains and beside gentle Isaacs Creek, the headwaters of the long and beautiful Kentucky River.

Papaw left home many times, but the most telling time was when he left — really left Daa and their boys. She had just been diagnosed with tuberculosis. In a coal camp, tuberculosis was held to be a slow death sentence. And she still had young boys at home — five of them. According to apocryphal tales told by cousins, Daa had told someone that Papaw, when he left, said he had to go because he did not want to stay and watch her die.

Given the common prognosis, his expectation that she would die was not unrealistic, many tuberculosis cases in the camps ended in death, but it was cruel to have said it out loud. Daa had been diagnosed with tuberculosis. During those years many tuberculin cases ended badly. But, this going away seemed most cruel if that was what he said, and if that was why he left. Some of us never accepted this story, but clearly, Daa never forgave Papaw for his thoughtless words, whatever was said, and silence often sat in the house like a deep fog when the two were together. If he said all those things, it did not enter into his grandkids ‘ heads as cruel as it now sounds. We could not get enough of his tall tales. His awful prognosis for Daa did not come through in his stories and his love of his grandchildren. Both grandparents, it seemed, feared being alone in the later years of their lives. Whether it was fear of being alone, or the threats of the labor wars in the mining camps that had led to his departure, Papaw left during the strike years of the 1930s. These were the troubled years that brought silence to later conversations. Daa, even in her anger, filled up those years with empty places that were only grasped when reading family letters and the snippets of stories shared by the sons. But, during those years, the family held together. Pine Mountain Settlement was part of that glue. Daa was angry but pragmatic. Her sons were resolute and creative. They never gave up trying to entice him back home. Daa was clever, and she found ways to carve out pieces of her dreams. It all would finally work out she believed.

The 1930s in Harlan County were not easy years, with strikes and union unrest, and violence. Daa’s “disease” could easily have been fatal, and so could so many other diseases of the day. A random bullet could have instantly broken the tight bonds of mother and children. Bad things happened, but they could have been much worse. In many ways, Papaw’s prognosis was just as stark as that of Daa. Black lung ended the lives of most miners, and the unpredictable cave-in of a deep mine could crush the life from a man in an instant. Union thugs could target whomever they did not like, and disease could randomly kill anyone. When Papaw left to take jobs in Detroit and the industrial north, or to Colorado, or wherever he went in his mysterious departures, I always believed that he knew he was saving his life and the life of the family. The industrial factories had their own labor strife and workplace dangers, but dying was not generally a common outcome in Pawpaw’s mind. When he left, I am sure he aimed to be lucky for later.

But Daa, with her lung disease, her tuberculosis, needed luck right away. Dr. Clark Bailey, a doctor in the town of Harlan, Kentucky and a Pine Mountain Board of Trustees member, who had diagnosed her disease early on, had found her a sanatorium in Louisville where she could possibly be cured. Dr. Bailey learned of an experimental treatment of the deadly disease in the Louisville program. Through Dr. Bailey, she had also learned about Pine Mountain Settlement School, a progressive and affordable boarding school for mountain children, and with his help, she started the process of enrolling her sons. Though Daa had only an eighth-grade education, she had been called on from time to time to teach in the coal camp school and later served as postmistress. She knew the value of an education, and she aimed for schooling for her sons.

When she learned from Dr. Bailey of the Pine Mountain program and that the sons could earn their education through a work program, she planted the seed of that idea in her sons. The older sons could pay their way through work and also earn money in the summer to help pay for their younger brothers and, later, perhaps, save funds for their mother’s care. The plan, as it turned out, was a good one and Daa’s tuberculosis was healed, the boys went to school, and Papaw was for a time not deep inside a mine. But, the wound of abandonment, the going away and Papaw’s long migration history, was not so easily healed.

WAR AND MIGRATION

In the mountains of Appalachia, wars also created migrants in the sense that many young men left the mountains and never returned, or if they did return, they carried with them the changes wrought by new and brutal experience but often romantic tales of far-off battles in far-off places. Papaw’s brother fought in the Boxer Rebellion and also in the Spanish American War and when he returned he brought the romance of far-away places. All but two of Daa’s five sons fought in WWII. One of the two sons died from a coal camp disease — chronic diarrhea. Another became a farmer. Daa cried when her sons went to war but her “babies”, as she called them even into adulthood, went anyway. Going to war was a noble and necessary act for the country and the sons adopted those noble ideals. They took on the journey to war with relish and looked forward to the chance to travel, to adventure and to do something that would stamp them with the noble entry into manhood.

- John Hayes – Army Recruitment notice 1

- John Hayes Army Recruitment notice 2

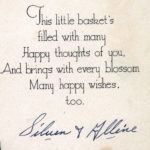

But not all noble ideals end well. When Uncle Silven, Daa’s oldest son went to fight in France, he returned to the mountains, in a coffin nearly five months after his death. His service was lauded throughout the community and within the family and by his wife, Alline. His body returned from the distant and foreign war to the war being waged in the coal camps as mines ramped up to support the war effort. His death filled the house with grief. His coming back brought foreign lands to the mountain family, and all the myths of exotic lands exploded with his death.

Silven’s story has been repeated many times over by Appalachian families and their mountain sons. The heroes, the wounded, and the families of the killed in action, like Daa’s family, shared how they were so proud of their heroes as they filled the rooms with tears. Silvan had been missing in action, and throughout the long five months it took to determine his fatal end, Daa wrote stacks of letters. When his death was confirmed, she shed tears of relief and of grief. Daa’s family and other mountain families then came face to face with another kind of tangled emotion, that of displacement.

Hidden behind the pride and the grief that war brings, was a growing distrust in the minds of some; a great fear of going away and the dangers it carried. Noble or not, the scars of displacement, of leaving home, were deep in the mental fabric of many Appalachian families. Who they were before the war and where the families found themselves following the war, were not the same.

- Silven Hayes. Mother’s Day Card, cover. [hay0004a]

- Silven Hayes Mother’s Day Card, Inside. [hay0004b]

When Uncle Silven went away, he went, not for family, but for some larger community, the nation, freedom, a cause, that we knew was somehow ours as well. We knew we also shared in his death because he fought for us, but we knew that his death was among many noble deaths and that we should be proud. We also knew that his going away had killed him. It was a going, a departure on two levels of our imagination and understanding. The soldiers who went to war and who came back either dead or alive created a community, a neighborly, a psychic and an emotional displacement in families.

When Silven’s body came back home, the conversations in our family and those families who had experienced similar losses turned. Daa’s other sons, her “babies,” were now determined to go to war, to also fight in the war. Daa’s fears were palpable all around her. She talked of nothing but their safe return until they were all back home. Her mind during those years was as displaced as a migrant’s must be. Her neighbors and our neighbors and their neighbors went to war, and the conversations revolved around the places of those war’s battles — past and future. Men sat on crates in front of the local post office and told tales of wars — past and future. The Civil War, the Spanish-American War, the Boxer Rebellion, and WWI. It was those conversations that prepared the next generations for war, for the long journey to some foreign country where, like Achilles, they would challenge an unknown enemy. It was not remarkable that my brother and my cousins, my friends went into the military to prepare for future wars. Later, the conversations around Daa’s table were ever more expansive as conservations began to “migrate” toward the wars in the world. We all became experts on the subject of war and the “enemy” and foreign lands.

While the elderly grieved war’s loss and the young stood lonely and confused on the edge of that large landscape of death and destruction, and noble causes, we all followed the conversations with them in our romantic notions. Later, when my brother went to war in Viet Nam and survived his many supply flights and sorties into Da Nang airbase, we stopped holding our breath and proudly watched him advance in his military career. Yet, we still understood that we were preparing and training for the next war and that war and migration were joined in creating new ideas and new places where those ideas would grow, but also where men die. It was a painful growth. We knew that what we were and what we would become was somehow tied to the outcome of wars and displacement — and migration. As Daa’s grandchildren grew up, as we grew up, the coming and going to Daa’s house seemed to grow, as well. Transportation changed, and travel became easier. Still, we always carried the memory that going was a kind of war that never ends and that coming back would have an end — could be the end — a finitude.

Our family continued to gather after the war, in the times of peace between the wars. In the 1950s we still gathered around the dinner table to tell stories. It remains a time of my best memories of going and coming back. The fried chicken was still shared with tall tales of the earlier war in the South Pacific, Navy training, guns, ships, airplanes, the sandy beaches of the Solomon Islands, the training for the Navy, and bravery. The boys waited for the stories with the eagerness of juveniles looking for heroes, and adolescents looking for the crisp edges of fried sweet potatoes. The girls listened with polite reverence, often admiration, and some sorrow — at least this one did.

When we were very young the stories lingered in our heads, and we went home and got our play guns and loaded them with caps and shot each other in mock battles of cowboys and Indians. We tuned our radios to the Lone Ranger and the Hi-Ho of Silver. I know we all thought of Silven in his casket, but it still did not stop us from romanticizing war and playing with guns. My brother and I were young and the Viet Nam war and his fatal air crash on Mt. Rainier were thirty years or more away. I had not yet migrated to California but my brother was soon in Utah majoring in aeronautical engineering and chasing forest fires in old Navy planes. We both still practiced the ritual of going back home every chance we got. Strange, the physical power of stories and the ritual of coming back. Neither of us could think of never going back.

Early on, the conversations of war had filled the imaginations of all the young-uns at our family table and those conversations had gradually given more meaning and nuance to the idea of going and coming back. Our going had punched a hole in the fabric of our isolation. As we grew, the coming back of our family members had made many of us wonder what was beyond the small world of our goings and coming back across a county, a mountain, a country, a world. The fragile fabric of family, forever held tightly together by the conversations across Daa’s extraordinary table. While we knew the lives that were ripped apart by war and the stories we heard, we then imagined and we then lived pieces of those family moments. As our younger generation aged, and our coming back to share stories and to listen to the voices of our relatives sometimes left us insecure, excited us, educated us, it prepared us for our own adventures to come. As we got older, we started to find that the stories sometimes conflicted with our growing understanding of the world and our loyalties to people and place. The stories, old and new gave us restless ideas. The coming and going and all the tales spun from those brief migrations fractured some of our loyalties and made some stronger. Our stories unsettled us just as surely as did our physical departures into our multiple worlds.

In my mind, I knew that my own migration and the migrations prompted by the war years of WWII had some common threads. The early war years were times of massive going and coming back for many families like ours in the Appalachians and across the country. The displacements were upending and made our younger generation restless. Going meant that our lives were fragile but it also meant we were brave. It meant that some of us would die in faraway places and some would come back with their mighty tales of adventure. But we all migrated. We a left “home”. Some near and some far. Our family, like so many others, was pushed and then pulled back time and again.

Papaw did not fight in any war, but war had raised the mystery of the going and coming back of Papaw to another level. It had made travel mysterious and set the imagination in flight. Now older, I hunger for new tales and new outcomes. I still want to know the adventures of Papaw while he was away. I still want to travel….. to go away and come back filled with stories. Now, I still want to hear the spirit of adventure in his tales like those we heard from the Uncles. But the memory of the gaze of my grandmother and the tension around the dinner table that always froze those conversations haunts me and gives the going a weight that I cannot fully understand or shake off.

Papaw’s stories of what he did in his personal war were never fully told by him. He came back, not as a hero, but as one who left his family behind. He did not have the stories to give honor to his departure or his return. His valor in coming back was never celebrated. But, I have never doubted its valor on another level. In some sense, he never came back because his migration had been a permanent fracture with Daa, but he came back for family. He came back before he ever started — to a place where he was not welcomed. His migration was the migration of an idea. He held fast to his idea that a better life was out there. Daa was firmly rooted in place. It was the ultimate battle of going and coming back. I like to believe that his going away was brave, but his return was heroic.

The icy stare of our loving Daa, our powerful grandmother, ended many of my grandfather’s stories before they began. Anything that might give credence to “That Man” and his adventures was censored by Daa. The going and coming back of Papaw would remain a mystery and that was that. For the grandchildren, Papaw was imaginary travel writ large. His untold stories of goings and comings would remain mysterious and compelling. Papaw’s life was, for me, a grand idea. It was the idea of a “better life”. Daa’s life was anchored to one place to which everything returned. That was her “better life.” Now I deeply believe that a “better life” is our own.

Many, many families in Appalachia have stories that revolve around going and coming back and are fueled by dreams of a “better life.” My family story is only one. War certainly filled many conversations in the cyclical migrations that constitute war’s outcomes. But strangely, it was the going of Papaw that pulled most strongly on my imagination. Many Appalachian fathers went away alone. It was not uncommon. But, a more common way of going was the whole family that packed up and went away together. It is the kind of going where place is abandoned. This going and coming back of Papaw’s mysterious travel — somewhere in the North, was the journey that was so very hard for many Appalachian families to process. It was a journey not to exotic places like Iwo Jima or France or the jungles of Batan. It was to Cincinnati, Indianapolis, Chicago and Detroit, and other centers of industrial production. It was this form of migration that was clearly a going — that took families and individuals from Appalachia away from the “home-place” and constructed the fabric of what we generally consider as the Appalachian family migration. It fractured many families or it made them stronger.

Today migrant families are spread throughout the world. What some of these migrant families shared with Papaw was not the journey itself, but a perception of a lack of responsibility to a place. Going North when the mines failed was a journey of faith as much as it was a journey of necessity. But the journey to an urban environment puzzled those who stayed behind. To not have land to work, to not pull your existence from inside the earth, to own your own earth, was to lack responsibility. The shift in lifestyle that came with the move to urban centers during the 1930s-1940s was monumental. The life of the Appalachian family would no longer be bound to the soil, and the context of the stories around the communal table would develop toward a new framework and a new conversation of “place” and deeds.

When the migrants came home from the urban North the telling of stories now had to capture for family and relatives left behind, their new and unfamiliar landscapes. They had to introduce new words, new traditions, new lifestyles, all often so alien that their descriptions, their stories were intrusive. The stories of migrant families became stories of urban survival, of bullying, of discrimination, of playing in streets and alleys. These were poignant stories tinged with unspoken longing for corn fields and mountains and rivers — for “their people. In many ways, these new stories fractured the bonds of families unless the story could be woven into the quilt of the extended family that had stayed put.

In Harriet Arnow’s novel The Doll Maker, going was an inventory of things to be missed, a litany of stories about hoeing corn, feeding the livestock, freezing in hard winters, walking barefoot in a creek. In Arnow’s novel, the migrants took their patchwork quilts, their “crazy quilts”, their heritage seeds for a garden, a string of shucky beans, their courage …. their fatalism. When they came back, the stories changed among their own. At their core, the celebrations of return were pure fatalism. Their life as a migrant was a violent story of being ripped from nature’s familiar arms, the enfolding of mountains, and the warm bosom of the family. As a family, they had been to “war.” Coming back was often a rant against the new environment or false boasting of wealth and the excitement of cities. Migration in hard times became a mantra writ large and passed along in the rich oral tradition of Appalachia. It is the dinner at Daa’s house.

Even deeper, the going became an all too familiar series of stories told over and over by those who experienced migration or those who witnessed migration’s impact on the extended family unit. Their stories became fusions of the stories told by migrants throughout the world. Their stories were war stories as well as economic sagas. A thousand times over, their stories were at their base the stories told by migrants from Mexico, Venezuela, Syria, Sudan, Yemen, the Rohingya of Indonesia, and so many more. We are a world awash with the psychic trauma of displacement — of having to come and now having to go.

Environmental disasters have added to the displacement saga. What distinguishes the Appalachian migrant from those now filling temporary camps throughout the world is the fact that most of the world’s migrants will not have the advantage of going back. War has obliterated “home. Today’s immigrats will become immigrants in a state of permanent displacement. Their displacement is our terror, the terror of never coming home. It is millions of stories with no family table to return to.

For every family going to Cincinnati, to any new city, to find work, to survive, to build a future, there are hundreds more on the move throughout the world. But, migration is not always immigration; a going and staying. Like Papaw’s going, migration is most like a yo-yo, – a constant motion of families. In Appalachia, going is often a continuous loop of going and coming back but it is bound together by a return to a common culture. For most of the Appalachian migrants, the departure was not a permanent exile — it was deeply believed to be temporary. The migration and the new place were malleable, and so were the people to some degree. For Appalachian families, the migration was a constant recreation of communities of support balanced against the need to stay connected to home, to the rural familiar. Coming back, in some cases, could take years, as it did in my case from far across the country. Or, coming back could be only the old stories around a new and permanent table in the new “home.” Most times, coming back was ritualized. It was part of being a family from the Appalachian mountains. It was required.

Living as a migrant is to adapt but retain. It is in its low moments to be reminded to never “get above your raisin’ and never forget. It is foodways raised to the level of a sacrificial offering. It is barter, not money. It is the noble dream carried in the back pocket billfold and the voice of ancestors in the head. For the migrant in the city, the physical state was dirt, crime, monotony, an urban prison where the walls of tall buildings replaced mountains. For most families from Appalachia who experienced leaving for urban centers, going required a coming back … a return to the cathedral of nature and the true familiar community where the memories could be refreshed or restored. When the migrants could not soon go home again, they pulled the vision of home from their dreams and were bolstered and awash in memories of themselves at home; they sought out other like-dreamers and formed centers of Appalachian life in their new cities. Today’s migrants from all over the world are like those Appalachian dreamers. In its essence, it is us all. Migration is not about “other.” It is about us.

SEE:

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH Coming Back and Going Some More