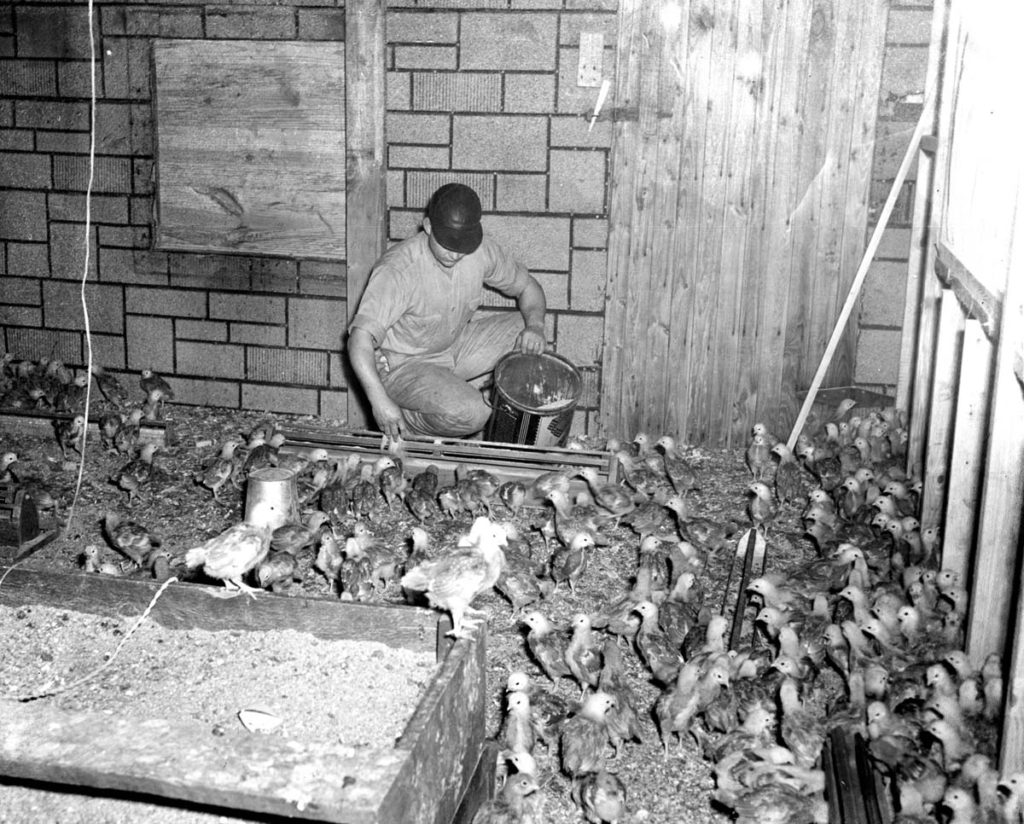

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH Poultry

Poultry house with young chickens. VII 64_life_work_017

TAGS: Dancing in the Cabbage Patch, poultry, chickens, eggs, Pine Mountain Settlement School, Harlan County, KY; farming; farms; foodways; Rhode Island Reds; roosters; sheep, Rhode Island Whites, Leghorns, William Hayes, Glyn Morris, Katherine Pettit, chicken houses, foodways, chicken and dumplings,

CHICKEN ‘N DUMPLINGS and MUTTON STEW

When dairy farming was no longer viable at Pine Mountain, the school farm returned to earlier farm ventures, including poultry. Chicken ‘n dumplings never went off the school’s food favorites list. The raising of sheep was another bucolic adventure but not one that found mutton on the table at Pine Mountain Settlement. It seems mutton never hit the pallet in the same way as chicken ‘n dumplings. Further, the brief trial of raising sheep placed too much stress on the local flora and available pasture-land. Complications with hoof disease from the constant damp fog and rain in the valley also created ongoing health treatments for the sheep and the costs of that care. Though there are many pictures of sheep on farms in the valley in the early years, these were sheep raised for their wooly fleece. The number of sheep on local farms dramatically declined as access to other livestock grew in importance and families were less dependant on the wool for weaving. By the 1940’s sheep were found on very few farms. but the number of chickens was growing. Later attempts at sheep farming sheep farming experiments at Pine Mountain School following the end of the Boardig School, but, again, disease and the high maintenance made the venture short-lived. Chickens, it seems, continued too come and go over the years, but neither have been contributing staples to the food supply at the School since the Boarding School years.

As poultry interests came and went over the years, and sheep were shuffled off the farm for longer periods, the work with poutry and with sheep continued intermittently capture the interest of agrarian at the School. The complications with hoof disease in sheep was only part of the reasons for decline in interest. The increasing institution of laws governing free-ranging livestock was a significant factor in the decline in raising wandering livestock — particularly pigs. The fencing of sheep furthered the burden on local farmland and also began to promote the erosion of hillsides from the contained livestock. Secondly, the introduction of cheap commercial fabrics was rapidly reducing the need for wool and home weaving was no competition for the industrial mill. Mountain sheep wool was notoriously full of brambles and dirt. It had little market appeal as it was also expensive to process. Sheep started to no longer be considered necessary farm animals in the view of local households and mutton , never high in the diet of the southern Appalachian, was hastened their departure. Sheep were not the sustaining critter of choice over the years — but chickens persisted.

Harriet Butler feeding chicken and chicks at iron pot cooker at Medical Settlement, Big Laurel. X_099_workers_2497_mod.jpg

Poultry had and has had a long and tenacious hold on Appalachian family farming. At Pine Mountain School, poultry farming had always played a role in supplying the school with eggs and meat. Of all the farming initiatives, chickens proved to be the most continuous animal husbandry venture at the School. This may have been due to the fact that chickens are relatively easy to manage and the yield in eggs over the life of the healthy hen can be considerable. Even today fresh eggs from family chicken flocks are a part of many city households though roosters are restrained. At Pine Mountain the sound of a crowing rooster was a familiar community song.

There are some memorable images of staff workers with chickens that suggest that they were an integral part of the operation of the School at the very beginning and remained so through most of its history. The same was true at the various satellite settlements near Pine Mountain. The following photograph of the Big Laurel Medical Center nurse, Harriet Butler, feeding chickens from her split hickory basket at the Medical Settlement in Big Laurel, suggests the close attention given this food source during the first years of the School..

Chickens (White Leghorns) tended by early staff. II_7_barn_275a

The hen and her chicks feeding next to the large iron pot has a certain irony as these pots were often used to cook up a good chicken stew or chicken ‘n dumplings. In the earliest years at Pine Mountain School and in the satellite settlements, the kitchens were outdoors, or partly outdoors. The staff cooked in large iron kettles such as the one seen above. Generally rigged on a tripod or hanging from a trestle, the large heavy pot was used to feed large groups and served as a kind of “crock-pot” that could slow cook food and tenderize that extra tough rooster. Chicken ‘n dumplings was a popular meal prepared in these large communal pots. Not all iron pots were equal, however. It would not eat well to follow soap-making with the stew of a chicken ‘n dumplings meal.

HOUSING THE FLOCK

Poultry farming at Pine Mountain had many levels of sophistication. From the beginning, the School maintained a large flock of chickens for both eggs and for chicken ‘n dumplings, and other poultry related meals. At first, only fences protected the flock and staff were given the responsibility of maintaining the flock and watching after their welfare, particularly attacks by predators — of which there were many including fox, great-horned owls, weasels, and bobcats.

Later, chicken houses kept the flock safe from fox and other marauders and like the Ayrshire herd, the flock was expanded. Various chicken breeds were favored over others for their egg production or for their meat quality, just as cows were sorted out for their milk quantity or its butter-fat content.

While milk was considered the most important food in the diet of the Appalachian family, eggs made a close second. It was for a reason. Milk and eggs came from herds and flocks that were relatively easy and inexpensive to maintain if natural foods could be found. It was also possible to grow the cow into a herd with the help of a bull and the small flock of chickens could produce the next generation of egg-layers with a little help from a rooster. A mountain family could often make-do with one good cow and a small flock of chickens. The two staples, milk and eggs also provided a sound source of protein for a minimum cost among mountain families.

[From an early staff letter. n.d, probably c. 1914 or 1916]

“This spring we have at last a herd of cows and a dairy. Two weeks ago our six new cows and bull, all Jerseys, were sent up from the Bluegrass, and today we had our first dessert made entirely of milk and eggs, we have a large chicken house and two incubators and have raised fifty-six chickens from the first batch. Two hundred more Leghorns are to come in from the outside world, and we think that by the end of the summer we will have 400 chickens. One worker devotes all her time to the care of the poultry and she has the most intelligent assistance from one of our older boys, age 15.”

While this may not be the “milk and eggs recipe” referred to in the worker’s notes, the following recipe is one that was favored by later Home Economics classes.

May 1935, as recorded in The Pine Cone.

CHOCOLATE PUDDING

3 cups of milk

1 cup of sugar

3 teaspoons of cocoa

1/8 teaspoon of salt

7 1/2 Tablespoons of flour

1/2 teaspoon flavoring

1 egg may be used

Heat the milk in the top of a double boiler. Have water in the lower kettle under the milk. In a bowl mix the sugar, cocoa, salt, and flour until thoroughly mixed. When the milk is scalding hot add slowly to the ingredients in the bowl stirring all the time. Return it to the double boiler, stir while it thickens for about 10 minutes. Then let it cook 20 minutes more. If the egg is to be added add some of the chocolate mixture to the beaten egg. When mixed return to double boiler to cook two minutes. Remove from fire. Let cool slightly and add flavoring. Serve with cream.

The Rhode Island White , now an endangered breed and few now exist, enjoyed wide-spread popularity in the 1920’s and 30’s for their abundant white eggs. Similar to the Wyandotte, the Rhode Island White was bred from the White Wyandotte, the Partridge Cochin and the Rose Comb White Leghorn. Like the Leghorns it was a robust chicken but also was prized for its high egg production as well as its full-bodied meat. In 1922 it was admitted to the American Poultry Association’s Standard of Perfection when the national conference convened in Knoxville, Tennessee. Many mountain families and farmers were introduced to it at that time.

With the industrialization of chicken farming, many chicken breeds were sidelined in preference for a few rapidly growing hybrids, particularly the popular Rhode Island Red chicken. The Rhode Island White slowly slipped from memory. Today the Livestock Conservancy has instituted a movement to recognize “Heritage Chickens” and counts the Rhode Island White among some three-dozen species facing extinction. Today the population of Rhode Island Whites is less than 3000 according to the Livestock Conservancy. Rhode Island Reds could take over the chicken kingdom in just a few cock-a-doodle-do’s.

All this discussion of the merits of chickens was not missed on Katherine Pettit in1932 and she cried fowl to Glyn Morris who had taken over as the new Director of the School and she rankled at the proliferation of Rhode Island Reds. Apparently, Pettit followed the future of chicken breeds quite differently from the several farmers at the School and also from Morris. Pettit was in line with the growing trend in the larger market. Quickly, the new director, Morris wrote to the President of the PMSS Board regarding the rationale for retaining the older breed and laid out the argument — and Miss Pettit’s preference. No doubt she crowed.

May 15, 1932

Mr. Darwin D. Martin

Martin Trust Building

Buffalo, N.Y.

Dear Mr. Martin:

In regards to Miss Pettit’s discussion against White Leghorn hens, I should like to say this: we have hens primarily for the purpose of producing eggs. White Leghorns have been developed for egg laying. The Rhode Island Reds that were here when I came weren’t worth the room they were taking. There is a difference in the weight of these two classes of hens, but not near enough to warrant keeping Rhode Island Reds in order to have a little more meat when they are finally killed.

The White Leghorns have been laying without a break since December. Reds would have broken long ago.

Sincerely,

Glyn Morris

Yet, by the middle of the 1940’s when the School attempted to make the poultry farm commercially productive it was already out of step with the growing industrial cycle of poultry farming. Too late for small-scale poultry markets and too small to compete with the growing number of large scale operations that began to supply markets throughout the country, Pine Mountain’s poultry farm efforts were not successful on a scale that could recover costs. The possibility of moving poultry farming into a commercial realm had been discussed many times as a means to save the School farm, but the timing, the times, the law and the market, were not in the School’s favor.

Even when the farm turned to egg production for commercial purposes it struggled. Like sheep farming, and like other farming practices in the remote valley, the commercial production of eggs, proved to be too complicated in the new tightly controlled egg markets. Transportation to market and the competition of the market and government regulations created additional costs and burdens on the operation of a large-scale chicken farm. By 1953, the poultry farming initiative had run its course. It was challenged by too many obstacles and was clearly faltering.

Poultry farming for meat had become even more daunting than for eggs as the rules and regulations surrounding the slaughter of meat or even the sale of live chickens was increasingly bureaucratic regulated for health standards that required additional equipment and manpower. Small operations found themselves squeezed out of the market. The larger poultry farms could produce eggs more cheaply through mechanized means and the costly regulations that limited the sale of poultry meat through the open market through complicated and expensive federal and state laws could be absorbed by larger poultry operations. The new markets and burdensome regulations were part of the “new” agriculture in the State and there was little room even for entrepreneurs to have a go at the rapidly changing commodity market. The new market was the end of Pine Mountain’s sale of poultry meat and eventually to its sale of eggs, as well.

For some, the end of the early chicken yard could not have come fast enough. Anyone who has had any long-standing relationship with a chicken yard knows that roosters come with most flocks as they were used to selectively fertilized eggs that hatched out the new flocks. Often aggressive, these rulers of the roost, the “rooster,” made a trip to the chicken yard a frightening experience for young and old. Flogging of intruders was common and generally tolerated to a point but excessive aggression could easily find the rooster in a savory Sunday stew — though seldom was it bragged that the meal was “Rooster ‘n Dumplings as roosters were not known to be the tender sort.

POULTRY – SELECTIVE BREEDING

In 1935 the breeding of chickens was an important topic in the industrial training program of the boarding school. Here Students learned about the health of the flock, its comparative worth as a meat, about best egg breeds, and how to kill and butcher a chicken. The following is an excerpt from The Pine Cone, May 1935, written by a student.

“One of the most fascinating problems connected with poultry management is the problem of breeding…

Some of the fundamental factors to consider are as follows; (1) Breed only purebred birds (if possible) of a well-established breed…. (2) Breed only from heavy producers. These are the birds that molt late in the fall. They are easily recognized by their healthy appearance and active dispositions. They are alert, bright-eyed, red combed and go singing happily far afield in search of food. Upon closer examination of the toe-nails will be found to be worn; the vent large, pale light pink, or upon long extra heavy production, bluish-white , soft and moist; the color faded or blacked from the eye ring, ear lobes, beak and shanks of the Mediterranean class, such as Leghorn and Minorcas; the pelvis bones long, thin, pliable and wide apart. These are the two bones located on either side of the vent. The egg must pass between these bones when it is laid. Consequently, with increased production, there is an increased distance between these bones. There is also a considerable distance between these bones and the keel or breast bone; the comb is smooth, full bright red in color, and has a waxy appearance. (3) Breed from mature birds both male and female. (4) Breed from birds with good appetites and with large well-formed bodies …”

White Leghorn chickens were good as a meat source, but as an egg producer, they excelled. The breed is known to produce from 250 to 300 eggs per year. This high production was a significant contribution to Pine Mountain’s breakfast and other menus.

ON THE TABLE

The following recipe found in the May 1935 issue of The Pine Cone was used in the Home Economics and Practice House fare.

SCALLOPED EGGS

6 hard cooked eggs

1 cup bread crumbs

2 Tbs butter or chopped chicken [fat].

1 1/2 cooked material [see below]

3 cups milk

6 Tbs flour

4 1/2 T butter

3 tsp salt

The cooked material may be spaghetti, potatoes, ground ham, cracker crumbs, flaked fish … Arrange the sliced eggs and other material in layers in an oiled baking dish. Pour the white sauce over the mixture, cover with crumbs and dot with the first amount of butter given and brown in a moderate oven. Serve in the baking dish.

To make the white sauce, melt the fat in a pan, add flour, mix well and add milk, stirring as it thickens. Add salt.

The Second World War also put severe limits on poultry farming, as many of the young men who worked on the farm at Pine Mountain went to war, and the local chicken stock was reduced due to rampant diseases that killed many of the brood at the School and in the surrounding community. The disease, probably coccidiosis, possibly parasites, such as worms, or mites, were all common in chickens of the era and particularly in flocks that were tightly confined. Any of these diseases can cause a wasting of the chicken and most of the diseases remained in the soil for some time. The parasites and coccidiodosis can only be combated by cleaning and removing the chickens and their houses. Severe cold or heat can slow the progression of some of the diseases, but such severe cold can also kill the flock. Permethrin, an unhealthy chemical solution, and quick lime were used effectively for a while at Pine Mountain, but mites and other parasites continued to persist in the flock and thrive in the damp mountain environment and in the confinement of the chicken-houses. Raising chickens in quantity required diligence.

Though maintenance of the flock was difficult at Pine Mountain it soon became clear that chickens were one staple that would keep the school eating during the difficult war years and pursuit of a remedy to the chicken disease should be sought. In March 1943, Pine Cone, published the following article

“CHICKEN AND DUMPLINGS TO BE SERVED ONCE AGAIN”

“With meat rationing and rising prices on eggs, Pine Mountain is going to purchase five hundred baby chicks.

The school is getting ready to make room for five hundred baby chicks which will be bought [as] soon as their new house has been constructed. Blue-prints have already been drawn for the brooder house which will be twelve by fourteen feet.

It will be located on the north side of the road [the road to Line Fork] near where the other chicken house used to be.

In another five to ten weeks, a larger house will be built to make more room for them as they grow larger. In the meantime, the students should not grow impatient, for it is just a streak of luck to have chickens again. In the three preceding years it was impossible to have them because of a disease which kills them, and which remains in the soil for several years afterward. “

While the stories abound regarding the Ayrshire herd and the long history of acquisition and maintenance of the herd, the nurturing of chicken flocks at Pine Mountain is also has a long history. In the Pine Mountain Community if one asks a mountain family about chickens, the stories, abound. The rooster that terrified the children with his long spurs and fierce territorial aggression; the slippery slopes of the chicken yard after a rain ; the particular way the grandmother wrung the neck of the chicken or how she chopped off its head ; the smell of wet chickens in their yard in the heat of summer; the night the fox found the chicken house; how the skunk stole chicken eggs; why crows steal eggs; the black snake in the chicken nest, and many more tales that run like colorful threads through the history woven into so many mountain families.

While the stories abound regarding the Ayrshire herd and the long history of acquisition and maintenance of the herd, the nurturing of chicken flocks at Pine Mountain is also has a long history. In the Pine Mountain Community if one asks a mountain family about chickens, the stories, abound. The rooster that terrified the children with his long spurs and fierce territorial aggression; the slippery slopes of the chicken yard after a rain ; the particular way the grandmother wrung the neck of the chicken or how she chopped off its head ; the smell of wet chickens in their yard in the heat of summer; the night the fox found the chicken house; how the skunk stole chicken eggs; why crows steal eggs; the black snake in the chicken nest, and many more tales that run like colorful threads through the history woven into so many mountain families.

The fox went out one stormy night

He prayed for the moon to give him light

He had many a mile to go that night

before he reached the town-e-oh … etc.

Following the brief attempts to resurrect large-scale farming at Pine Mountain through sheep and poultry, the Pine Mountain Board of Trustees in 1951 called for a thorough analysis of the farm at the school. The so-called Chang study, “Whither Pine Mountain,” while not centered on the farm alone, addressed industrialization and the issues of the farm head-on. In 1951 industrialization would be the winner and it would forever change the direction of the School and its integral links to traditional farming.

During the Morris years and later the Benjamin years, the margins of profit for the farm were small, but the educational value of farm practice supported the farm program and the two Directors put their energy behind the farm efforts. Too, both Morris and Benjamin had been raised on a farm and knew the issues associated with managing a farm and the discipline that was required to maintain a well-run farm-school. Both realized the farm’s educational value. Morris clearly wanted to retain the farm program, but also began to have his doubts regarding the financial viability of the program as the School struggled to maintain a boarding school and compete with the growth of local schools for students. By the end of H.R.S. Benjamin’s tenure, the financial picture at the School had changed markedly and the educational programs had shifted to non-residential programming which eliminated the farm work-force. The Trustees called in several consultants and evaluated the costs of the farm operation against the sustainability of the School. The 1951 Fu Liang Chang Survey of PMSS , particularly, signaled an end to farming as it had once been exercised at the School. The economics of the Study indicated a downward spiral for small scale farming in the mountains of Eastern Kentucky and elsewhere in the nation. Pine Mountain’s demonstration work was not enough the bring new and effective farming methods to the mountains. Geography and efficiency were clearly at odds and more clearly the farm was in trouble as a model as few in the community could afford to invest in the machinery to maintain the increased scale of farming methods that would produce a profit.

Chang wrote:

The School farm has been facing an acute problem of labor since 1949, moving from over-supply to scarcity through the change from a boarding high school to a consolidated primary school. It was compelled to purchase a number of items of labor-saving machinery to run the farm. It has gradually changed its management with major emphasis as a practicing farm to that of a community testing and demonstration farm, with not a great deal of success so far. The subsistence farmers feel that the school can well afford to purchase the equipment which would not suit their farms of a few acres apiece. This has kept further apart the school farm and the subsistence farms of the community. It seems that the problem before the school farm is how to break down its agricultural improvement program into many small projects, some of which will meet the needs of the subsistence farms and the supplementary farms of wage-earners, and how, in cooperation with the county agent and the community organizer (after one is installed), 4-H Clubs and other rural organizations, to “sell” these projects to the community. Unless this is done, the school farm will remain a model farm, but not a community demonstration farm with the purpose of raising the standard of living of the people.

By 1953, farming on a large scale at the school came to a close with the departure of the farmer. As there were no educational programs to benefit from the maintenance of a large farm practice and pressure from the Board to engage diverse small projects was not producing results as labor was fragmented. The reliable labor in the form of community students and other salaried workers from the community was not in the institution’s budget. The last rooster had crowed. The farm and the poultry operation was forced to close down and much of the farm machinery and implements were sold to raise revenue for the school. In 1953 the farm manager, William Hayes, left the School for employment with the Kentucky Division of Forestry at Putney, across the mountain from the School. where his knowledge of the land set the course for another career.

CHICKEN N’ DUMPLINGS AGAIN

Always a central part of any home-coming, chicken n’ dumplings is a recipe with many variations. “Slickers” or “Puffers” no matter, they are all consumed with gusto.

Pine Mountain student, Flora Patsy Hall Martin, class of 1945, can still produce a rib-sticking dumpling at the age of near 90.

See also: DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH – CHICKEN HOUSES

GO TO:

The isolation of the region was slowly but dramatically altered by roads, particularly

The isolation of the region was slowly but dramatically altered by roads, particularly