Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 09: BIOGRAPHY – Visitors

Series 18: PUBLICATIONS RELATED

Fu Liang Chang (1889-1984), Berea College Sociologist

“Whither Pine Mountain?” 1951

Survey and Needs Assessment

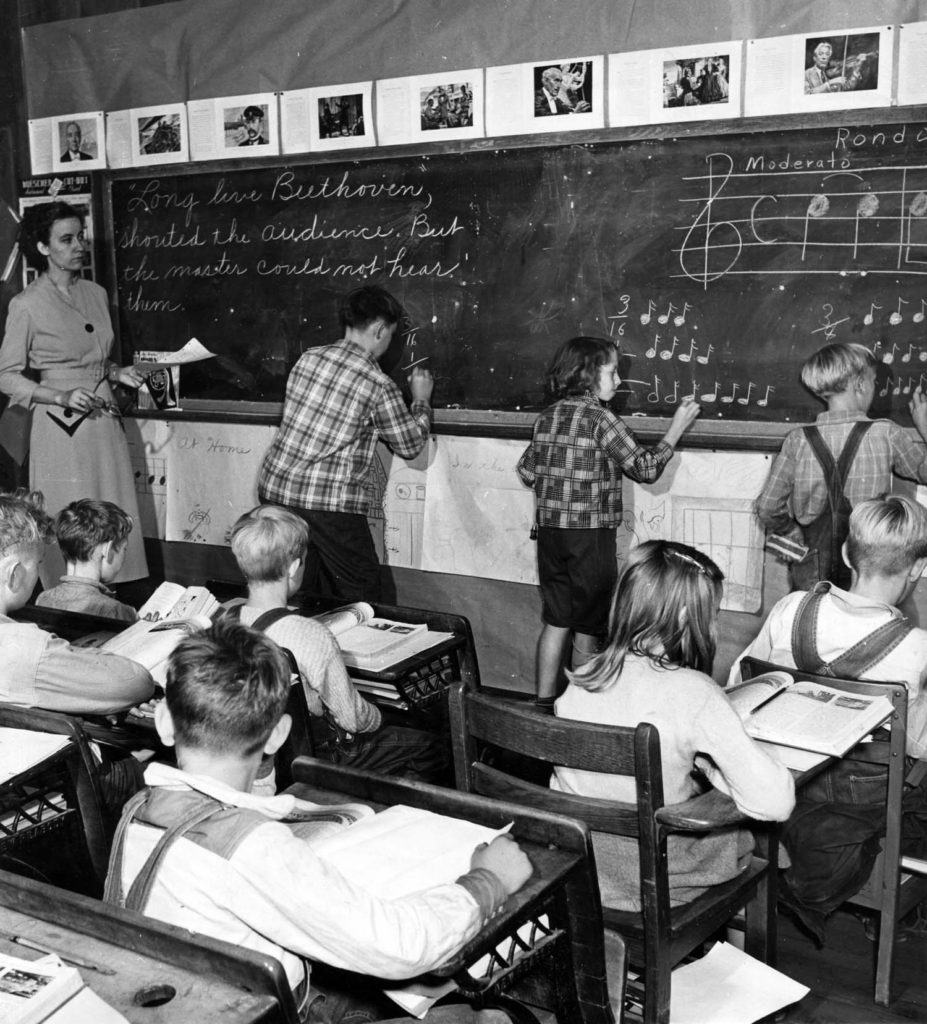

01 Classroom at Pine Mountain after consolidation with Harlan County Schools.[Teacher – Golda Pensol ?] [54_Life_Work_Children_Classes_001]

TAGS: Fu Liang Chang, Pine Mountain survey, educational reform, Berea College, Community Schools, Harlan County Board of Education, Dr. Francis S. Hutchins, PMSS Board of Trustees, Burton Rogers, Yale-in-China (Yali), Ellen Churchill Semple, communitarian point of view, rugged individualism, community organizers, agrarian myth

FU LIANG CHANG 1951 Whither Pine Mountain?

A Survey of Pine Mountain

The Fu Liang Chang Whither Pine Mountain?, a survey of Pine Mountain Settlement School, has been cited by many scholars as the pivotal tool that pushed the transition of Pine Mountain Settlement from a boarding school within a local community to a school that was part of a maelstrom of rapidly shifting educational and industrial reform sweeping rural communities across the nation.

RATIONALE

The brief eleven-page survey conducted in December of 1951, by Chang, an employee of Berea College, was made at the request of Dr. Francis S. Hutchins, President of Berea who was recently assigned President of the Pine Mountain Settlement School Board of Trustees. The study was necessitated by the dire financial situation of the boarding school brought about by the shift of educational programs within the geographic region and the evolving post-war economics. Cooperative and consolidated schools, more commonly known as Community Schools, were seen as new and promising educational models. In 1951 Pine Mountain joined with the Harlan County School system in the adoption of the new consolidated school model. The shared responsibility brought much-needed revenue to the settlement school from the Harlan County Board of Education and enabled continuing maintenance of the large infrastructure of the settlement. Teacher’s salaries, bus drivers, and bus maintenance, as well as rental income for the classroom space paid through the Harlan County Board of Education, significantly eased this difficult transition period for the School.

INSTITUTIONAL STUDIES

Throughout its one-hundred-year-plus history, Pine Mountain has been studied and re-studied and then studied again. The mountain institution is a remarkable test-bed for sociology, history, environmental studies, economics, ethnology, linguistics, education, religion, and a multitude of other interests. Generally focused on the many cultures found within the Southern Appalachian region, and Harlan County specifically, some have said of the School that it is “ever surprising in its surprises.” Especially, those who have made a deep dive into the archive at the Settlement School, remark on the wealth of knowledge in the material. Yet, what seems to be the most remarkable feature of the School is the resiliency of its educational focus and its mission.

While there have certainly been challenges over the years, the consistency of the School’s mission has remained intact. Uncle William Creech (1814-1918), one of the donors of the land, whose generosity and wisdom helped to shape the institution, set forward a timeless idea. It is a vision of a school that would perpetually serve the community, the nation, and the world with a fundamental set of ideals:

… I have heart and cravin’ that our people may grow better. I have deeded my land to be used for school purposes as long as the Constitution of the United States stands. Hopin’ it may make a bright and intelligent people after I’m dead and gone.

Studies by outside agencies and also independent scholars have often served as a counterpoint to ideas of self that are found in local cultures, and as a signifier of the local. These various formal studies such as this study, the so-called 1951 Chang Survey, “Whither Pine Mountain?,” and also the Roscoe Giffin Study of Pine Mountain conducted earlier in the summer of 1950, take issue with a narrow “local” and attempt to bring Pine Mountain Settlement forward into a new vision of the future. Both the Chang study and the Giffin study mark an important period of transition in the School. The years immediately following the closure of the boarding school and the succeeding program-focused trajectory that reached into the county of Harlan, encouraged more of the surrounding community to join in on the challenges of change.

Both the Giffin and the Chang studies came through Berea College interests, having been commissioned by the Berea College President, Francis Hutchins, who had recently assumed a role on the PMSS Board of Trustees. In 1949 Berea became an affiliate of the rural Settlement School following a mutual agreement between the two institutions. While the Pine Mountain 1949 closure of the mountain School’s boarding program was necessitated by economics and the recent Worls War, Berea’s affiliation with the School was one of long-standing connections, starting with the China experiences of President Francis Hutchins and Burton Rogers.

Hutchins, as the Yale-in-China Director, had hired Rogers to teach at the Yale school, known as Yali. When Yali was overrun during the Japanese incursion, Rogers left China and later found placement at Pine Mountain in 1942. The two men assisted H.R.S. Benjamin, the last Director of the boarding school program, make the actual difficult administrative transition. While there is no fiduciary responsibility to Pine Mountain, Berea faculty and the college President established an agreement that placed succeeding Berea College presidents on the Pine Mountain Settlement School Board of Trustees from 1949 forward.

ONE OF MANY IN-DEPTH STUDIES OF PINE MOUNTAIN SETTLEMENT SCHOOL

The Chang study, “Whither Pine Mountain?” was not the first in-depth study of the institution. The earlier and later studies of the educational institution; some formal and others not so much, are found in scholarly research articles, personal autobiographies, the journalism of visitors, the travelogues of “passer-throughs,” and the diaries of staff “insiders.” Whatever the source, the studies and commentaries provide rich windows into life at the Settlement School and into the surrounding Appalachian community and offer valuable counter-points to the Chang study and others who attempted to dissect the major changes WWI had brought to the world.

THE COMMUNITY

The community under study in the Chang survey is the community covered by portions of five school districts in Harlan County that were consolidated at Pine Mountain in 1949, the year of the closure of the boarding school. The creation of the so-called “consolidated school,” consisting of the five district schools of Creech, Little Laurel, Big Laurel, Divide, and Incline, also included, by virtue of geography and not “district,” the community schools of Abner’s Branch and Turkey Fork.

In his brief but thorough survey, Chang evaluates not only the educational needs but also the medical and agricultural needs of the community served by Pine Mountain School. He builds on the more sociological, formal, and in-depth study of his colleague, Dr. Roscoe Giffin, and like Giffin, is quick to acknowledge the limiting aspects of the regional geography, particularly on the practices of subsistence farming. He cites the prior Giffin study that indicated “only about 450 acres or 10% of the land holdings of families were cultivated in 1949 by over 50% of the families with an average of less than 5 acres.”

In some ways, it was the Ellen Churchill Semple model narrative of economic possibilities limited by nature. But, to the Semple model Chang added the limitations of the current and evolving (U.S.) economic system. In his study, Chang cited only limited feasible employment for those who dwelled in the area such as mining, manufacturing, trades or part-time farming, and development of logging and forest products. Ironically, or perhaps, not, Semple accompanied Pine Mountain Settlement School founder Katherine Pettit and Berea instructor Penniman, on her first formal trip into Eastern Kentucky in 1899.

A PERVASIVE COMMUNITARIAN POINT OF VIEW

What Chang’s study generally recommended for the School was a pervasive communitarian point of view for all concerned parties. Following this perspective, the Chang survey is little different in its conclusions from other earlier and later studies that found the sense of community and teamwork to be at the center of the meaningful work of the institution. Chang’s recommendations were community-centric approaches and were intended to be the guiding impetus and critical to any planning going forward. In this respect, the study was not so much a counterpoint to the current culture but was largely a familiar road map well traveled by many of the early leaders at the School.

In addition to the familiar planning and community-centric approach, Chang also made allowances for local cultural influences and like the historians in his current century, Chang saw the “rugged individualism” of the mountain pioneer to be a restraint on the cooperative development of the area, i.e., a move to accommodate rapid industrialization. True to his own education, and that of his supporting institution, Berea, Chang encouraged a Christian values model as a starting point and as a model for scale. It was a model that found local favor. His suggestion that the “community organizer” serve as the “transmission line between the community and the school,” still remains a strong foundation of the School’s work. That same model provided a base for the community organizing work that characterized the region in the late 1960s and 1970s War on Poverty campaigns some years later.

SURVEY SUMMARY

In section III, part 6, “Team Work,” he summarizes the survey result:

To be community-centric Pine Mountain Settlement School has to include in its planning different types of adult education without sacrificing the efficiency of its consolidated school. The belief is that education for children and for adults, as has been pointed out before, are complementary and mutually strengthening. The excellent teamwork among the staff members of the consolidated school will be further expanded and extended to the work with and for the community. While the community organizer will serve as the main transmission line between the community and the school, there are many other live wires connecting these two ends, through the children of the school, patients at the hospital and cooperators with and visitors to the farm and workshops. The members of the staff of Pine Mountain Settlement School will no longer be individual school teachers and specialized personnel in health, agriculture, woodwork, weaving and administration, but a team of purposeful community builders. A team of twenty community builders following an integrated plan will accomplish many times more than what can be accomplished by twenty individual workers. Through their different lines of service, they will present to the people of the community the same ideals and ideas of the Christian way of life, follow the same scale of Christian values and press forward towards the same goal of a prosperous, enlightened, and happy Christian community. The teamwork of the whole staff rather than the brilliant work of any individual will carry the day in making Pine Mountain the community-centered school.

Importantly, the Chang study is a study that aligned with the larger historical milieu of the nation. Many of the changes occurring at Pine Mountain may also be seen throughout the United States as it continued its recovery from WWII. The economic, social and political shifts in the U.S. were creating rapid introspection at both the national and the personal level.

In 1955 the work of Richard Hofstadter captured the rapid changes of the first quarter of the 1950s. His Pulitzer Prize-winning book, The Age of Reform, was greeted by an audience that was eager to make sense of the many economic, social, and environmental shifts going on in the country. Perhaps one of the most difficult reforms to grasp throughout Appalachia at this time was and continues to be the myriad interpretations of the “Christian way of life.” However, Hofstadter’s historical assessment and that of other scholars of the day was in tune with Chang’s sociological views, particularly his grasp of the impact of agrarian reforms. It was Hofstadter who coined the phrase, “agrarian myth” and famously said, “The United States was born in the country and has moved to the city.” In many ways, Pine Mountain Settlement and like institutions were and are America’s birthplaces of community work.

AGRICULTURAL REFORM

While the consolidation of the Pine Mountain Settlement School with the Harlan County schools system was an educational reform model that was echoed in many parts of the country, the agricultural reforms across the land were also radically changing the landscape and influencing decisions at Pine Mountain. National agrarian reforms were at work even in the hard-scrabble Appalachian farms and their subsistence models or their agricultural practices.

The elimination of the boarding school and the subsequent reforms took a substantial toll on the struggling Settlement School farm with its accompanying loss of boarding school farm labor. Fu-Liang Chang, a native of China, and an intellectual in the growing communist perspective adopted by Mao, could easily imagine a forced agrarian life ahead for the community. China under Mao, was particularly sensitive to the agrarian sector and Mao’s agricultural reforms as tools to reshape Chinese society, were brutal. Further, Mao was born in the south-central and largely agricultural Hunan province, where Yali was located. The coming years in China surely must have looked very bleak for the Changs.

In 1951 when Berea’s President, Francis Hutchins, assigned the study of Pine Mountain, to Fu-Liang Chang, he did so with some knowledge of the background of Chang and his wife Louise. Both Hutchins and Chang had attended Yale University but at different times. Hutchins and the Changs had met in the 1920s when they both held teaching positions at Yali, the Yale-in-China program then located in Nanchang, China in Hunan Province. Hutchins’ exemplary work in leadership at Yale earned him the position of the Director of Yali in late 1933.

Both Hutchins and his wife Louise and Fu-Liang Chang and his wife, also called Louise, were at Yali when the Japanese invaded China and occupied the school in 1937. The situation at Yali was horrific and the bonds that Hutchins and Chang shared ran very deep. The Japanese incursion that devastated Yali has been described as unimaginable, but as Fu-Liang Chang followed the course of China after the Japanese invasion, he was particularly cognizant of the changes brought on by the Communist takeover in the late 1940s. While Hutchins and Burton Rogers came back to the States when the Japanese invaded, Fu-Liang Chang and his wife remained and suffered under both the Japanese as well as the later Maoist regime. The years of Mao were in many ways even more difficult for the Changs than the short period of the Japanese incursion.

SHARING ‘ACROST’ THE SEA

As the Communist pressures grew in China, Fu-Liang and his wife planned their departure from their homeland. In 1949 Chang was accepted into the Yale Divinity School and they left for America. The growing oppression of Mao in China would have been fresh in Fu-Liang Chang’s mind when he came to Yale in ’49. And, when in 1951, he was asked by Hutchins to consider a study of the Pine Mountain Settlement and to help develop a strategic plan for the School, it is not surprising to see elements and reflections of his China trials in his work. Fu-Liang’s career in China had focused on sociology, rural reconstruction, forestry, and botany. He held the position of director of the middle-school department at Yali and Hutchin’s belief was that Chang’s skills and the many lessons learned in rural China would be useful in understanding the changes occurring in rural Appalachia and specifically at Pine Mountain. As Fu-Liang Chang set about considering “Whither Pine Mountain?” the vision of his homeland under Mao must have weighed heavily on his mind.

Following his brief stay in the Yale Divinity School program, Chang was enticed to come to Berea College and he was given a place on the faculty of the college in 1951. For Chang, the fit was perceived to be in keeping with his life’s mission, that of addressing rural poverty and the severe lack of resources that accompanied that poverty. The familiar academic environment at Berea and at Pine Mountain allowed Chang to use the skills he had gained from Yali and Yale, and to meld those skills into a knowledgeable analysis of the Pine Mountain issues.

Further, Chang had a direct connection to Pine Mountain. His Yali colleague, Burton Rogers, who had headed the Literature department at Yali had left China when the Japanese invaded, and he had also studied at Yale and was since 1942, at Pine Mountain as the principal of the evolving Community School program. Their exchange of information gave the study a rich and informed base, albeit one framed against the Japanese experience, and the growing distress caused by Mao, that only they could know deeply.

Chang had both the credentials and the motivation for a study of Pine Mountain. There he also found friends and the perfect field work for a course he developed for Berea in the sociology department. The course, called Rural Reconstruction of Underdeveloped Areas, pulled many ideas from the students at the college whose homes were in the region, as well as his own global ideas that had been formed by his direct experience. Chang had seen the upheaval and the political treachery of Mao’s claims of sympathy and legitimacy to rule and had lived the results of that treachery. He would naturally be a cautious evaluator where reconstruction was concerned.

Again, Pine Mountain had brought its lessons to those “acrost’ the sea” and those “acrost’ the sea” had brought theirs to the mountains of Eastern Kentucky. The mutual sharing and the shared sense of community was the knowledge base that helped to transition Pine Mountain into what Richard Hofstadter, in 1953, called the new “Age of Reform.”

**Further reading: Teaching in Wartime China 1928-1939, University of Massachusetts Press; First edition (May 24, 1995)

OUTLINE OF THE FU LIANG CHANG SURVEY

I. PINE MOUNTAIN COMMUNITY

(1.) Area and Population

(2.) Natural Limitations and Human Adjustments

II. PINE MOUNTAIN SETTLEMENT SCHOOL

(1.) Its Past Achievements

(2.) Its Present Status

III. WHAT OF THE FUTURE?

(1.) Recognition of Existing Limitations

(2.) Special Contributions of Pine Mountain Settlement School

(3.) Community Organizer

(4.) Suggested Fields of Organization for Community Service

(5.) Concerning the Hospital and the School Farm

(6.) Team Work

GALLERY: FU LIANG CHANG 1951 Whither Pine Mountain?

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_001.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_001a.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_002.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_002a.jp

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_003.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_003a.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_004.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_004a.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_005.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_005a.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_006.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_006a.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_007.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_007a.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_008.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_008a.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_009.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_009a.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_010.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_010a.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_011.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_011a.jpg

- Whither Pine Mountain chang_012.jpg

Return To:

PUBLICATIONS RELATED Guide by Author

PUBLICATIONS RELATED Studies Surveys Reports Guide

VISITORS Guide to Consultants Guests Related Friends of PMSS

See Also:

FU LIANG CHANG (ZHANG) Visitor – Biography (in progress)