Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 09: Biography – Friends, Visitors

Ladies of the Kentucky Aid Society

Blanche Rannells, Cleveland, Ohio

BLANCHE RANNELLS Our Mountain Neighbors 1924

TAGS: Blanche Rannells; Blanche Rupe Rannells; Blanche Brewer; Our Mountain Neighbors; Ladies of the Kentucky Aid Society; Pine Mountain Settlement School; Hindman Settlement School; New York City; philanthropy; civic responsibility; Appalachian settlement schools; community; industrial training; poetry; Ann Cobb; rural settlement work; mountain settlement work;

[We are looking for more information about Blanche Rannells. Please contact office@pinemountainsettlementschool.com if you have information to share.]

Blanche Rannells, the author of Our Mountain Neighbors and founder of the Ladies of the Kentucky Aid Society and speaker at the Civic Club at Tipp City, Ohio on April 21, 1924, was a staunch supporter of mountain settlement schools. When she spoke to the Civic Club at Tipp City, Ohio in 1924, about settlement schools in the Southern Appalachian mountains, she focused on the need for women to support the mountain institutions of Pine Mountain Settlement School and Hindman Settlement School, the earliest rural settlement schools in the Southern Appalachians.

Mrs. Blanche Rannells Brewer, mother of Blanche Rupe Rannells was a resident of Argos, Indiana. She was connected to Hindman Settlement and then to Pine Mountain through mutual friends who were apparently associated with the Women’s Clubs of Kentucky. Her father, the Rev. J. C. Rupe, was the pastor at the Argos United Methodist Church in Argos, Indiana, for many years and was also, in later years, a pastor for the Evangelical United Brethren denomination. Blanche U. Rupe, one of Rev. Rupe’s three daughters, was influenced by a growing trend among the clergy and women’s clubs of the day, that sought to address what they believed to be a growing problem with “poor whites” in the mountains of the South.

In the 1950s’ the Rupe family appears to have moved to Altoona, Pennsylvania where Rev. Rupe served as Superintendent of the E.U.B. (Evangelical United Brethren church) in the area. The efforts of the Evangelical United Brethren were instrumental in the formation of Red Bird Mission School in Bell County, Kentucky. It is not known if Rev. Rupe or his daughter had any later relationship with the Red Bird Kentucky mission school, which is similar in many ways to Pine Mountain Settlement and Hindman Settlement schools and is located in adjacent Bell County, Kentucky.

Just how Blanche Rannells first connected with Pine Mountian is not fully known, but she is recognized as the founder of the Ladies of the Kentucky Aid Society. During that active time, she was married to Mr. Rannells and was living at 1853 East 75th Street which appears to be a Cleveland, Ohio address and not a Kentucky address.

The connection of Appalachian settlement schools with such intensely urban women as Rannells was not unusual for the time and the growing social awareness of Rannells fits well with the growing interest in social service occupations of women, particularly those exposed to the urban settlement movement. Henry House in New York, Hull House in Chicago, and other settlement houses in the large eastern and mid-western cities attracted a growing number of women who were being educated in elite eastern women’s colleges, particularly Vasser, Mt. Holyoke, Smith, Wellesley, and other women’s colleges. It is unclear where Rannells fits in this educational picture or what prompted her interest in the settlement movement, but it appears that she first encountered Pine Mountain through Kentucky contacts at Hindman Settlement.

Her contact with the newly formed school at Hindman planted a seed that led to her trip to Hindman in 1923 and later to Pine Mountain to see for herself the work that was being done in the two institutions. Her own women’s club, the Ladies of the Kentucky Aid Society, was a central focus of Rannells and suggests that she had strong connections with Kentucky Women’s Clubs. Her report focuses on a variety of contributions by the Society she formed. The Aid Society record, as recounted by Rannells, describes the philanthropic work of the Society in 1922 and its steadfastness to the idea of mountain “uplift.”

Mountain “uplift” was part of a growing vocabulary about the region that began at the turn of the century and by the 1920s was well accepted. Samuel Tyndale Wilson’s small book, The Southern Mountaineers wrestles with descriptive language of the region in 1902 when he attempts to isolate the Southern Mountaineer or “Our Neighbors” into classes. A similar struggle may be seen in the essay by Rannells, “Our Mountain Neighbors” which follows the account of her Kentucky Aid Society and her description of her visit to the mountains of eastern Kentucky. The muddled idea of “poor mountain whites” creeps into her language throughout her essay-talk to potential donors, and feeds into the commonly held belief that Northern “do-gooders” put their stamp on settlement work in the mountains. This debate, promoted by David Whisnant in his contested work, All That Is Native and Fine: the Politics of Culture in an American Region (1983) seems to never rest and is lately energized by the publication of J.D.Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy (2017). Further, the publication of Nancy Isenberg‘s White Trash: the 400 Year Untold History of Class in America (2017), muddies the water by focusing our attention on the volatile language of class and points the reader toward a growing perception of anti-intellectualism in the Appalachian population.

Samuel Tyndale Wilson, a Presbyterian minister and former President of Marysville College in Tennessee, notes in his small book The Southern Mountaineer (1902), that the descriptive language for the southern mountaineer often uses “poor whites” and “mudsills” and other descriptors, but he is quick to note that the poverty seen in the mountains is not unlike that seen in the slums of many of the major cities of the day. He goes on to say

“Some writers have gotten into the habit of calling us modern Appalaches “mountain whites,” a term that implies peculiarity and, inferentially, inferiority. We are not deeply in love with that nomenclature. It sounds too much like “poor white trash,” the most opprobrious term known in the South. Fancy how it would sound to hear the inhabitants of the Buckeye State spoken of as “Ohio whites” ! …. There is no evil hint in the word mountaineer in the Appalachians, but rather the reverse — an honorable ring. Better use no class name at all, if possible’ but if one must be used, let it be a generous one.” [Wilson, (1902) The Southern Mountaineers p.20]

Blanche Rannell’s 1924, talk on “Our Mountain Neighbors” captures the essence of prevailing trends in social service work, class consciousness, and confused approbation. and the Southern Appalachian programming in many women’s clubs that followed the national settlement house trends of the first quarter of the twentieth century. Cleveland, Ohio, was a central location of a large settlement house movement. By the 1920s, the Cleveland settlement houses became centers for philanthropic work that soon created a very competitive atmosphere for raising money for mountain “uplift.” And, by the 1930s, the urban settlement movement had shifted to unified social services, often not located in the service site, and more frequently found in rural communities.

TO THE LADIES OF THE KENTUCKY AID SOCIETY 1922

- 01 To the Ladies of the KY Aid Society rannells_01

- 02 To the Ladies of the KY Aid Society rannells_02

- 03 To the Ladies of the KY Aid Society rannells_03

TRANSCRIPTION

To the Ladies of the Kentucky Aid [sic] Society

As our little society has now been in existence five years a fine[? resume of its work may be of interest to our charter members as well as to our newer members who are not familiar with the history of the early activities of the society.

The records show that on January 16th, 1917, there met at the home of Mrs. Rannells, 1853 East 75th St. [Cleveland, Ohio] six of our present members, Mrs A.A. Benis, Mrs A.B. Diss, Mrs F.T. Jones, Mrs E.A.Roberts, Mrs. G. F. Smith, and Mrs B. [Blanche] U. Rannells. It was decided at this meeting that monthly dues should be twenty-five cents and that meetings should be held the first Tuesday of each month at the ladies’ homes to serve [?] for the Settlement Schools at Hindman and Pine Mountain, Ky. Our membership had gradually increased until it now numbers sixteen.

p.2

During the five years, only one member, Mrs. George Warden, has permanently resigned — not from lack of interest in the work but on account of sickness in her home.

The stability of the membership is convincing evidence of the deep interest and enthusiasm of the ladies.

Nor has this spirit been confined to the limits of our own little circle. Two of our number, with the aid of a friend, are supporting a scholarship at Pine Mountain, and one of the same two ladies [has] interested her Church Society to the extent that it has also established a scholarship at Pine Mountain and, in addition, is making and sending clothing to the school.

Some of our members have responded most generously to the appeals of the two schools for contributions for their running expenses. Some have given very liberally of money and material for our own use, thus enabling us to furnish supplies far beyond the purchasing power of our modest dues.

A brief summary of data compiled from the Society’s account book shows that in five years, one hundred and fourteen packages have been sent, the postage on which amounted to $66.42. Cash gifts to the two schools totaled $47.00. The merchandise account shows an outlay of $459.34. Cash contributed by members and interested friends, $217.75. Records show that 285 books have been collected but it would be safe to say that at least 100 more have been sent of which no account was kept.

OUR MOUNTAIN NEIGHBORS

In Blanche Rannell’s essay, “Our Mountain Neighbors,” written in 1924 as a fundraising plea, the well-worn theme of the “poor mountain white” rings loud and clear throughout her writing. In the essay, there are also echoes of the literature at both Hindman and Pine Mountain Settlement School from the same period. The inspirational tales found in such literature as the Pine Mountain Settlement School Notes, particularly the 1923 Notes, obviously written by Ethel de Long, are echoed in the message of Blanch Rannell’s motivational talk. Though the bulk of her offering is the first-hand account of her brief journey into the mountains to visit Hindman and Pine Mountain, many of the stories and events described by Rannells may be found scattered throughout the letters and histories of the two settlement schools.

GALLERY

OUR MOUNTAIN NEIGHBORS 1924

- 01 Rannells, B. “Our Mountain Neighbors”

- 02 Rannells, B. “Our Mountain Neighbors”

- 03 Rannells, B. “Our Mountain Neighbors”

- 04 Rannells, B. “Our Mountain Neighbors”

- 05 Rannells, B. “Our Mountain Neighbors”

- 06 Rannells, B. “Our Mountain Neighbors”

- 07 Rannells, B. “Our Mountain Neighbors”

- 08 Rannells, B. “Our Mountain Neighbors”

- 09 Rannells, B. “Our Mountain Neighbors”

- 10 Rannells, B. “Our Mountain Neighbors”

- 11 Rannells, B. “Our Mountain Neighbors”

- 12 Rannells, B. “Our Mountain Neighbors”

- 13 Rannells, B. “Our Mountain Neighbors”

- 14 Rannells, B. “Our Mountain Neighbors”

- 15 Rannells, B. “Our Mountain Neighbors”

- 16 Rannells, B. “Our Mountain Neighbors”

TRANSCRIPTION

OUR MOUNTAIN NEIGHBORS

A paper read by Mrs. Blanche Rannells of Cleveland, Ohio before the Civic Club at Tipp City, Oho, April 21, 1924.

Also read before the Parent-Teachers Association of North Richfield, Ohio, on December 6, 1924.

Your Program Committee unconsciously made an error in not classifying today’s entertainment as a “Reading”, using the word in a literal sense, for when I was honored by an invitation to appear before your progressive club, I reserved the privilege of reading what I had to say about “our Mountain Neighbors.”

In view of the fact that your club, as a member of the Ohio State Federation of Women’s Clubs, is expected to investigate the subject of illiteracy in America, and inasmuch as this subject is closely related to the one under consideration this afternoon. it was suggested that I should present some data on American illiteracy. While data will be very brief it may prove as surprising as it illuminating.

Those of you who religiously read the Ladies’ Home Journal may recall an article in a recent number which is my authority for the startling statement that in enlightened America there are more than five million people over ten years of age who are classed as illiterates, which means that this number can not write in any language and it is assumed, if they cannot write, neither can they read. Five hundred thousand of the five million are between ten and twenty years of age, which is evidence that a new generation is coming on quite as neglected as its predecessors.

Every loyal American should blush with shame at the statement that in New York State there are 400,000 illiterates, in Pennsylvania 300,000, Illinois 173,000, Massachusetts 146,000, Ohio 126,000, Connecticut 67,000 and so on. Yet all these states boast of some of the finest colleges, universities and other cultural institutions in the country.

p.2

Records of enlistments in the World War disclosed the deplorable fact that thousands of men who volunteered their services and Iives, if need be had to sign their papers by mark because they had never had a chance to go to school.

The fact that we rank tenth among the nations the scale of literacy should rouse us to a sense of our obligations as citizens to do our part toward raising the standard of literacy in America so high that we shall head the list!

Let us now turn attention to the subject for this evening’s consideration. ‘Our Mountain Neighbors’. Modern methods of communication and transportation have so nearly annihilated time and distance that by using the work neighbors in a broad sense we may consider those who live several hundred miles from us as our neighbors.

Radio has proven such a powerful factor in putting us into communication with almost the entire world that we no longer feel we are strangers to the people of far distant cities and countries.

In consideration of these facts, we feel justified speaking of the mountain people or the adjoining state of Kentucky as our neighbors.

Ex-President Frost of Berea College, Kentucky calls the Southern Highlanders “Our Contemporary Ancestors,” the people with whom time has stood still, shut away as they havAmerica’som the great streams of progress that have swept by and beyond them, leaving them isolated and remote in their mountain seclusion.”

People who are unfamiliar with the ancestry of the southern mountainers fail to realize that in their veins flows the purest Anglo-Saxon blood of our nation.

It was their forefathers who, in search of freedom from personal, political or religious persecution, left their mother country and braved the

p.3

dangers of the sea in order to reach America’s shores.

Impelled by the spirit of adventure, they pushed their way westward into the Blue Ridge, Allegheny, and Cumberland Belts. Some, being veterans of the Revolutionary War, sought the mountains to claim the land to which they were entitled through “Land Grants” issued to them by the Government.

Others were detained indefinitely in the mountains on account of sickness or for other reasons and so hewed logs and built the cabins which were destined to become their permanent homes.

Locked in by nature’s barriers. generations spent their lives in these isolated regions, living in the most primitive manner in windowless log cabins and enduring the hardships known to early pioneers.

Many of the present generations of mountaineers possess the same sturdiness of character as did their ancestors. When a “mountain boy of today draws up a notion to get an eddicaton” as he puts it, he is as indefatigable in his efforts to attain his goal as were his forbearers. who surmounted every obstacle which might prevent them from establishing a home in the primeval forests of America.

The well-known author John Fox [Jr.] who knows mountain people as but few do, says of them:

“As a race they are proud. sensitive, hospitable. kindly obliging in an un-reckoning way that is almost pathetic, honest, loyal, in spite of their common ignorance, poverty, and isolation; they are naturally capable, eager to learn and easy to uplift.”

We should be proud to claim such a type of people as our neighbors and consider

it a privilege to lend a helping hand to them in their struggle to better the living conditions which have resulted from their mountain environment.

The natural topography of their surroundings precludes their following any pursuits which would fit them for any mercantile occupations.

p.4

They are of necessity an agricultural people and on account of their inaccessibility to markets, there is o incentive or necessity to produce any more than will be consumed from one season to the next.

It is the consensus of opinion of those have made a study of social problems related to the mountaineer that their most crying need better educational advantages and until these are provided it is better for them

not to leave the mountains and make a futile effort to compete with skilled labor in the commercial world.

To this end, many churches have established schools through the southern mountain ranges and some twenty years ago the Christian Temperance Union of Kentucky Joined this educational effort.

In 1899 this organization sent a group of young women into the mountains of southeastern Kentucky on a camping tour of investigation to discover the needs of the people and the best methods of ministering to these needs.

These young ladies spent three summers camping in different parts of the mountains studying seriously the social problems of the people.

A history of their experiences put in story form, entitled Quare Women was written by Lucy Furman, a worker at the Hindman Settlement School. This ran through several numbers of the Atlantic Monthly a year or more ago and was doubtless read by many of your numbers. For the benefit of those may not have chanced to read the story, permit me to relate some of the events connected with the establishment of the first mountain settlement school in the United States.

During the camping trips referred to, “singing, sewing. cooking and kindergarten classes were taught, entertainments were given. homes were visited and friendly relations were established with the men, women, and children of three counties.”

“At the earnest solicitation of Uncle Solomon Everidge, who, at eighty years of age, walked twenty miles to beg the women to give a “chance” to

p.5

his grand- and great-grandchildren, and because of the offer of land and lumber for buildings, the Settlement School was started at Hindman, the county seat of Knott County on Troublesome Creek.”

The original property consisted of a frame school house of five rooms, a rented cottage for teachers and four acres of ground. At the end of 22 years the school owns 225 acres of land (including a coal mine) and had twenty-two buildings used for various purposes.

The present school enrollment is 394, over 100 of the number being children from distant parts of Knott adjoining counties who live at the Settlement during the school year.

The curriculum covers a wide scope of instruction which is as follows: Kindergarten, Intermediate, High School, Music, Agriculture, Physical Education, Handwork, Woodwork, Home Nursing, Sewing, Weaving, Basketry, Cooking and Laundering.

The Social Service work includes the Library, High School Club, Camp Fire Groups, Women’s sewing club, Design and Dressmaking Shop, Mother’s Club, Community Club, Bible Class, Practice Home Teas, Rest Home for Country Women and Fireside Industries Department which is conducted to aid in the disposal of bedspreads, baskets and all article made for sale by mountain women in their homes.

There is a cottage used as a “Practice Home” where six girls of the Industrial High School course learn practical homemaking, becoming proficient in all the duties that fall to the lot of a mountain housekeeper.

A valuable branch of work is the Extension Department which sends workers to country homes to teach nutrition. health, swing, cooking and Sunday School. At Christmas time this department sends a large number of trees to remote schoolhouses where gifts and entertainment are provided for young and old, some of the latter hearing for the first time, on such occasions the Christmas Story!

page 6

As one of the main objects of the school is to train the children in better methods of living, the management has worked out a system by which each child is assigned some household duty for a given time, the girls doing, in turn, the various kinds of housework according to their ages and ability, while the boys do the milking, feeding and care of stock, gardening and farming.

A graduated scale of wages according to age is paid to children for their work and the amount earned is credited on their scholarship account. Of course, all are not able to earn the $150.00 which a scholarship costs., the balance being paid either by parents or by donors to the Scholarship Fund. Sometimes the memory of a deceased person is perpetuated by the endowment of a scholarship by friends or relatives.

The Hindman School was exceptionally fortunate in having as its founders two of the original half—dozen young women “who went on the expedition into the mountains, namely, Miss May Stone and Katherine Pettit.

Katherine Pettit at Big Log. [kingman_046b.jpg]

At the time this school was founded it was 45 miles from a railroad but in 1916 the Chesapeake and Ohio Railroad built a spur which comes within 16 miles of Hindman.

In striking contrast to Ohio’s paved highways, the most common type of road in the mountains is a rocky creek bed. The faithful horses which travel these obscured roadways seem to show superhuman instinct and intelligence in picking their way over the uncertain courses, seldom losing their footing.

Mr. J. C. Campbell in his book. The Southern Highlander in his Homeland,

page 7

gives the route for a 50-mile cross country trip from Hindman to her sister school at Pine Mountain in Harlan County, Kentucky.

The directions follow: Go up Trace Branch of the right fork of Troublesome Creek; down Betty; down Carr to the mouth of Defeated; up to the head of Defeated; over a mountain; down Bull’s Creek to the north fork of the River [Kentucky River]; down the River a mile to the mouth of Leatherwood; up Leatherwood four miles to Stony fork; up Stony Fork to the head; cross the mountain; follow down the least branch on yon side of the mountain to Line Fork; up Line Fork to the headwaters of Greasy Creek; down Greasy until you “come to the place you are aiming at.” I can assure you that no part of such a route has any semblance to the Dixie Highway!

It was my good fortune six years ago to realize a long-cherished hope to sometime visit this school in which had bee so deeply interested for ten years or more. I accompanied a party of three young ladies of Cleveland who were workers at Hindman.

The most interesting part of the trip began when we left the train at Lackey, Kentucky, to begin the 16-mile drive to the school. Our Cadillac was a common road wagon with sideboards, a necessary provision to prevent our baggage fro falling out when the road suddenly became a couple of feet higher on one side than the other When you learn that we were seven hours driving the 16 miles, you will know that we were never in any danger of violating mountain traffic ordinances against speeding!

We arrived at the school at 9:00 p.m. I confess that when darkness began to fall I longed for the sight of a good, old Ohio paved road and experienced some misgivings of ever again seeing my family “in the flesh”!

It was comforting to learn as we reached the end of our journey that the school’s guestroom was in the Hospital Building, for one who is unaccustomed to riding over rock creek beds is apt to be “somewhat the worse for wear,” and possibly in need of a nurse’s services.

page 8

I was happily disappointed the next morning to find myself quite fit for [the] two-mile walk to the home of a granddaughter of Solomon Everidge who pleads to have the school established at Hindman. A few days later we visited his widow who had remarried and at the age of 50 years

began the work at basket-weaving.

She pointed with great pride to the sash which she bought when the school received its first carload shipment. paying for it with beans, honey, and eggs.

Uncle Solomon vigorously opposed having the logs cut to put the window in but Aunt Cordy persevered, and after the work finished she said she scarcely had a chance to sit by the window as Uncle Solomon stationed his favorite chair beside it and spent all his spare time sitting In it and looking down the creek. Verily! the ways of some men are beyond understanding.

The two weeks of my stay were a succession of novel and interesting perturbances [?] such as getting lost in the mountains, taking an eight-mile horseback ride, slipping off a treacherous footlog into Troublesome Creek and attending a “funeral meeting” in a little wooded graveyard near Hindman.

The evenings were delightfully spent sitting before the fireplace in Miss Lucy Furman’s Cottage, listening to a group of boys telling ‘hant [haint] tales’ or to one of girls singing the old English ballads handed down by their forefathers.

Miss Stone, the head of the Hindman School, possesses an inexhaustible fund of stories gleaned from her 25 years’ experience in the mountains. She relates a most pathetic incident which occurred one summer morning when the group of W.C.T.U. ladies from the “Blue Grass Region” were camping in the mountains.

Plans had been made for an all-day trip, and as they were about to start, a tall gaunt woman appeared at their tent and asked to be shown how to

page 9

make the kind of biscuit they had served the day before when she had been their guest at dinner. In the kindest possible way, they expressed their regret that circumstances would prevent them from showing her that morning but insisted that she should return the following day when they would gladly teach her.

With a look of deep disappointment on her face, she reluctantly turned to leave, saying: “I thought that you as knowed [you] had come to show us as don’t, but you hain’t.”

Another story of a more cheerful vein is told of one of the schoolgirls who at Christmas time was convalescing from a severe case of typhoid fever which had caused all her hair to come out.

Her Christmas stocking was taken to the school hospital and given to her to empty. When her happy task was almost completed she brought from the depths of the stocking two pairs of side combs such as were in vogue at that time. Holding them up for inspection she grasped the humor of the situation and laughingly exclaimed: “Two pairs of side combs and not a hair on my head!”

The end of the two weeks allotted to my stay at Hindman came all too soon, bringing to a close one of the most delightfully memorable visits I ever expect to have.

As reluctant as I was to leave Hindman, I was equally eager to start on the second lap of my journey, the objectives of which was the Pine Mountain Settlement School in Harlan County, fifty miles away “as the crow flies.” Not feeling equal to the cross country trip by the route described by Mr. Campbell, I was obliged to drive 22 miles to the railroad by wagon the trip consuming ten hours to get around the spur of Pine Mountain, required a long trip by train which took me to Dillon which, by the way, is merely the name on a more or less dilapidated shed. After leaving the train came a 6-mile ride over a mountain on a mule guided by a man sent by the school to meet me.

page 10

The ascent to the top of the ridge was quite gradual but the descent was so steep that I preferred to walk most of the way rather than take a chance of slipping over the mule’s head.

Needless to say, I drew a long sigh of relief when we reached the level ground and I got a glimpse of the old log house near the main gate at the entrance of the school.

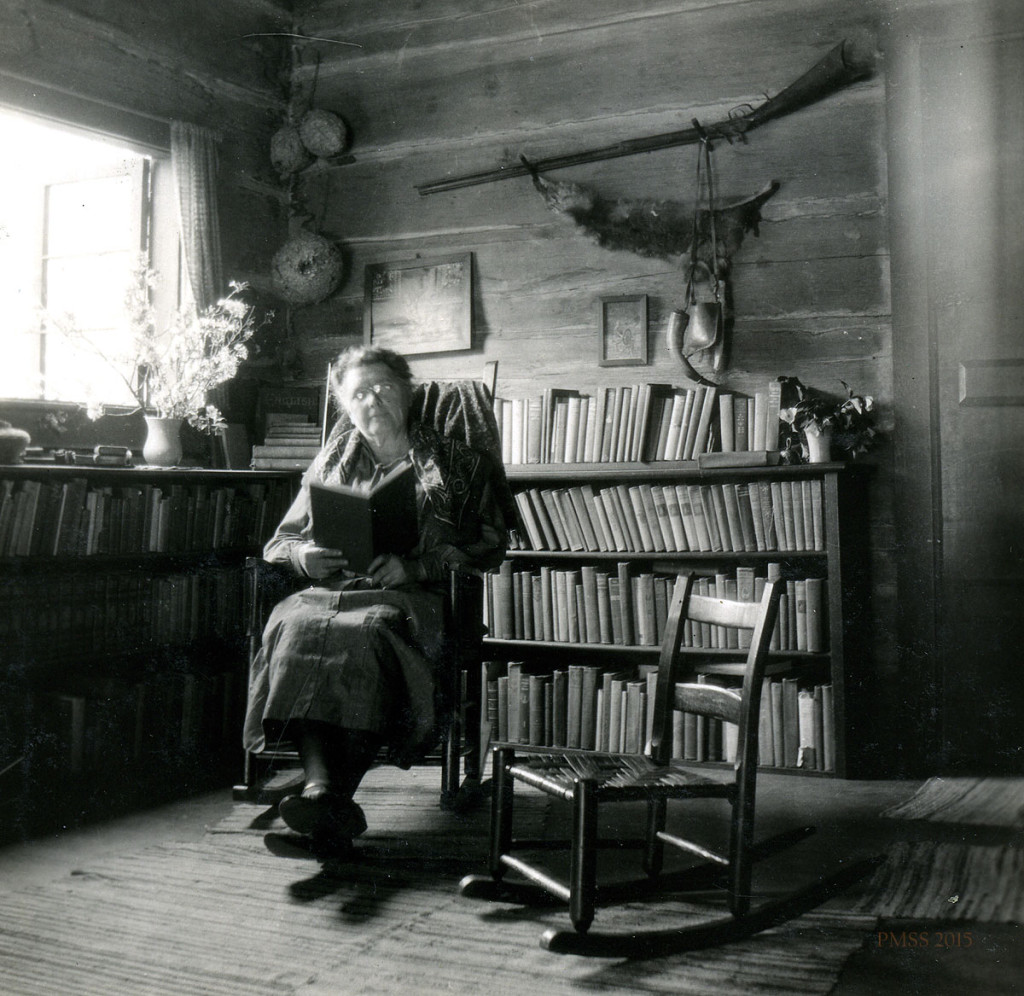

The Pine Mt. School was established in 1913 by Miss Katherine Pettit and Miss Ethel de Long. The former, associated with Miss May Stone, founded the Hindman School and the latter served three years as its [Hindman’s] Principal.

Ethel de Long in white hat and woman with 7 children. hook_album_2blk__025.jpg

Miss de Long tells in a most interesting way of its [Pine Mountain Settlement School] beginning. “The ground for the first buildingof the School was broken May 15,1913, but its real beginning dates back 30 years when William Creech first conceived the idea that there ought to some day be a school at the headwaters of Greasy Creek. Working on his farm by day and at his blacksmith’s forge by night, far away from the discussion of modern educational ends, alone he developed a great idea of education. He believed that farming should be taught and the hand industries should be kept alive, that teachers should know more than book-learning — in short, he wanted a school that would arouse an interest in the arts of the farm and home.

Because of this remarkable conception, when he learned that Miss Pettit and Miss deLong were wanting to start such a school he offered all his land 136 acres, if they would establish a school at Pine Mt. The people within a radius of 7 or 8 miles pledged money, lumber and labor. The first tree cut for the 7-room log house which was the first building erected, was felled by a 7 year old boy who worked from sunrise until sunset at his silf-imposed task. When the house was completed he slept under its roof as a pupil of the school.”

Big Log. cobb_alice_030

It was a herculean task to build up a school in the heart of the mountains

when building materials had to be hauled several miles from the nearest railroad.

pag 11

In the 11 years of its existence, fifteen or more buildings have been erected.

The system of management of the two schools, Hindman and Pine Mountian, is practically the same. Some of their social problems differ as the Hindman School is in the town of Hindman while Pine MountainSchool is several miles from any village.

Nature has provided an ideal setting for the school, “the strength of the hills,” seeming to be reflected in

seeming to be reflected in the sturdiness of character of the pupil. It was indeed a revelation to see how the work of such an institution could be done by children even under supervision!

Those of you who are interested in welfare work for children may be shocked by the statement that last Sept. “30 children who entered this school together were nearly 450m pounds underweight. In two weeks regular rest and wholesome food had produced a gain for the group of 147 pounds!” If you could see the homes these children come from and know the character of their food, you would no longer wonder at the statistics reported by the school nurse.

Let me try to picture to you one of these homes. Imagine if you can the utter solitude and loneliness of a life spent in a windowless log cabin “at the head of a hollow” with none but the sounds of nature to break the sepulchral stillness. No traveler ever chances to pass the door for the winding footpath which leads to it does not extend beyond it.

Within it is even more cheerless, especially in winter, for sunlight cannot penetrate solid walls of logs. The fireplace must serve the double purpose of furnishing light and heat. A touch of color is lent to the interior of strings of “burney” red peppers and hanks of wool of various colors suspended from the rafters. Long ropes of “shuckey beans” decorate the walls waiting to be shelled when needed for food. [The writer was obviously not familiar with “shucky beans” which did not require shelling to be eaten. As most times, the beans were cooked shell and bean.]

page 12

Beds which sometimes are “built in” occupy the corners of the room, according to the size of the family. In the better class of cabins, the walls are sometimes papered with newspapers. The furniture is of the crudest kind and very little of it. Cooking utensils are extremely limited in number and there is a decided dearth of dishes and other table equipment. Napkins and tablecloths are “an unknown quantity.

With no sanitary provision for wastewater or refuse of any kind, what wonder is it that hookworm, typhoid fever, and tuberculosis develop in this type of home?

As to the social diversions of those living in the fastnesses of the mountains, there are absolutely none. When we stop to consider that these people have the same natural craving for entertainment and excitement that is innate in all human beings, need it be a matter of great surprise that they resort to Indulging in “moonshine” in their homes to satisfy this craving?

A concerted effort is being made by the Settlement Schools to establish community centers such as Pine Mt. has opened at Line Fork, 6 miles from the [main] School. This plan was urged by Mr. J. C. Campbell who had charge of the Southern Highland Division of the Russell Sage Foundation, carrying out the Folk School plan of Denmark.

The people along Line Fork were so eager to assist in the development of this system that they offered logs and labor for the erection of a six-room house in which lives a trained nurse, two teachers and an industrial worker who teaches classes in sewing. cooking, playground, Girl

Scouts, Mothers’ Clubs, and Sunday School.

The nurse has provided what she calls a “Loan Closet” which is equipped with sheets. pillowcases, nightgowns, thermometers, hot water and other equipment necessary in sickness which is not found in mountain homes. As the name indicates, the contents of this closet are loaned to

page 13

families if they are needed and greatly facilitate the work of the nurse.

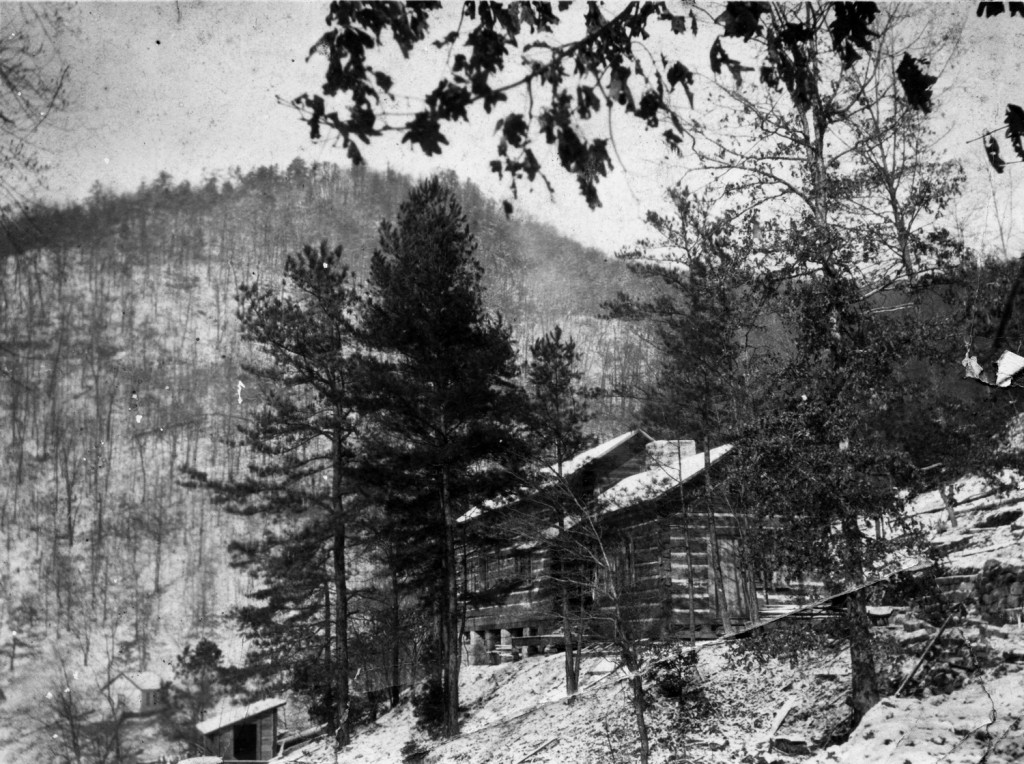

Four miles in an opposite direction from the school is a ‘Medical Settlement at which a woman doctor and a nurse are stationed. In a recent letter from Pine Mountain, they said: “We could tell you spectacular stories of the doctor and nurse who live there, how they ford full streams on horseback, crawl over foot logs to reach patients and take care of some cases under impossible conditions.

Medical Settlement- Big Laurel. Log cabin on snowy hillside. [big_laurel_3343.jpg]

The question is frequently asked: What has been the influence of these schools on the community?” If it were possible to compile statistics of the moral influence of schools of this type, it would doubtless be found that if possible more has been accomplished for the moral uplift of the adult population than in the education of the children.

As evidence of the improvement in Knott County where the Hindman School is located, Court Records show that while the County had the highest criminal record in the state in 1902 when the school was established, from 1907 to 1917, a period of ten years. not a single murder was recorded on the docket. A County Judge attributes this remarkable change directly to the influence of the school.

The feud spirit for which Kentucky has been famous hag almost died out in the regions of these schools. Children no longer boast of the number of notches on their father’s gun, a notch being cut for each man killed. Some of the schools’ most prized possessions are guns brought by boys entering school and voluntarily delivered as mute evidence of their owner’s determination to abandon customs common to feudists.

Before these schools were established Christmas in the mountains was looked

page 14

forward to as a time for drinking, shooting, and general carousing. But that is all changed now. It is a genuine religious festival, celebrated as it is with us.

A mountain visitor to the entertainment at Pine Mt. School when it was three years old made an observation which is interesting. He said: “Well, Christmas hit used to be the rambaning’est, shootin’est, killin’est, chair-flingin’est day in the hull year, and now look what a pretty time we’ve had today. I didn’t know you could get so many folks together and have such a peacable time. I never did come to one of your Christmas trees before, but I seed you never had no killin’ at ’em yit so I come this year. ”

Community gathering at Christmas with outdoor tree and bonfire at Pine Mountain. hook_album_2blk__027.jpg

It seems almost incredible and is indeed surprising to know that some of the school children become so homesick they run away and go back to their cheerless desolate homes.

Miss Ann Cobb, a teacher at Hindman and a poetess of of growing fame, gives in verse the soliloquy of a small new boy at school, as follows:

I’ve seen quare folks and places.

Everywhere I’ve been

But the right down quarest

Is the school I’m in

Jest afore her passing

Mammy got my hand,

Not to go a wanderin’

Doless through the land.

So I joined the work-school

Allus heared folks say

If you craved high learnin’

They could show the way.

Gee—oh. boys, the vittles

Cheese and rice they’ll eat

Soup and fancy pudding

Served us once for meat.

But I never follered

Being choosy much

What I mind is doing

Woman’s work and such.

Milking cows three times, too,

Feeding hogs and hens

page 15

Packing water buckets

Women’s work, not men’s.

Then the bells a-ringin’

Every hour or so

Like to turned me franzied

Knowin’ where to go.

Tell you when to study

Tell you when to eat

Tell you when it’s bed—time

And when to wash your feet.

Still. the big boys like it

Never seem to go

Reckon I could try it

Another day or so.

These mountain children are “diamonds in the rough.” Their minds when polished by education acquire a brilliancy which is reflected in splendid scholarship and even leadership in many cases,

Two years ago when the Hindman School held its 20th anniversary it was found that among its alumni were weavers of cloth and baskets, teachers, doctors, civil and electrical engineers trained agriculturalists, woodworkers, builders, writers and preachers.

Letters from former pupils generally end with the words: “Whatever there is in me, whatever success I may achieve, I owe it all to the Hindman Settlement School.”

With such a record of achievement. can there be any question as to the uplifting influence of these schools or as to the desire of the children to get an education when it is known that there is always a waiting list of six or seven hundred? The heads of the schools say the very hardest work they have to do is to turn away children when they beg to be given a chance to get an education.

Is not America failing to utilize some of its most valuable material for building high-grade citizenship when it neglects to educate these rugged children of the mountains?

page 16

Was there ever a time when, as a nation, we stood in greater need of honest, fearless, upstanding men. Men who have the courage of their convictions, men who have not become contaminated by the evils of 20th century civilization, men who have high sense of honor and still higher standard of loyalty to their country?

Kentucky gave us such a man as Abraham Lincoln and there are thousands of his type today in the seclusion of her mountains who are patiently awaiting the dawn of the day when they shall be emancipated from their shackles of ignorance.

Could any more noble and more uplifting work be undertaken by American women than to break these fetters which bind “Our Mountain Neighbors”?

A paper read by Blanche Rannells of Cleveland, Ohio before the Civic Club

at Tippet City, Ohio on April 21, 1924.

Also read before the Parent-Teachers Association of North Richfield, Ohio.

on December 6, 1924.