Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 09: BIOGRAPHY

Series 34: RELIGION

ALICE COBB STORIES

Migration From Hinterlands to Industrial Area

c.1940

Ella Wilder, daughter Barbara, and Brit Wilder. Brit and Ella worked at PMSS for over 40 years. [X_100_workers_2603d_mod.jpg]

TAGS: Alice Cobb Stories, Migration From Hinterland to Industrial Area, c.1940, Alice Cobb, Brit Wilder, ice storm, Laden Trail, Joe Wilson, Chris Anderson, Columbus Creech, Nolan Store, Nolan farmhouse, Bill Coots, Harrison Coots, Bailey Hill, Harlan KY, social services, coal mining, WWII, Church of God Holiness, lay preachers, mountain people, Community Girl’s Group, Stella Taylor, Mr. and Mrs. Glyn Morris, coal industry

ALICE COBB STORIES Migration From Hinterlands to Industrial Area c.1940

TRANSCRIPTION

[Transcribed from typewritten pages with handwritten edits and notations. The text below has been slightly edited for clarity.]

Page 1 [cobb_migration_001.jpg]

During my early years at Pine Mountain the Joe Wilson family lived far down Big Laurel Creek, — a mile or two from the mouth which empties into Greasy Creek and we saw very little of them. We heard a good deal of course, for Joe was a rather well known lay preacher, called by a voice to preach and entirely illiterate. Gospel said that whenever anyone gave him anything he gave it away before his family could get hold of it, and they lived in poverty and rags in a filthy, much exposed one or two room cabin. There were Joe and his wife, and Albert 15, Mathias 14 [‘Thias], Bessie 13, Tabitha 11, George 9, and Harmon 5, besides several dead, and there was Aunt Jane — old Aunt Jane Turner, who lived with them. And of course, there were the endless neighbors and relations who crowded around this open fire when they could get kindling to fix one, most of the time.

So far as we know, Joe never had any occupation at all, although he used to say that he gave up coal mining, his real calling in life, to take to the farm because of his wife. She wouldn’t hear tell to his working in the mines after they were married. It seems also that she was an extremely religious woman, member of the Church of God Holiness, and that she brought about his salvation in a miraculous way, and so effectively that Joe not only became a saint but he also became a preacher. He did say one time that he never could claim to be a learned man, but the Lord by a miracle had teached him how to read, so that now he could read the word. This was obviously an overstatement, for when he was preaching in the houses or district schoolhouses around, he always kept one or two of the young “scholars” living about on the front row to read aloud the verses. Then Joe preached from the verse read, by inspiration. One time one of the scholars played a trick reading aloud about how Jonah swallowed the whale, and Joe preached for two hours from that text. A visitor from the Pine Mountain school discovered the error after a while but probably it went unnoticed by most of the audience. Mountain preaching is so beclouded with amens and hallelujahs that histrionics cover many an error in fact. Also, the mountain people are too innately kind to take advantage of a public mistake of this kind. One might be pine blank mean enough to play the joke, but the rest wouldn’t be mean enough to pay attention.

We knew then about the Wilsons in an informal way for a long time. After the Community Girl’s Group was organized the students made their house to house visits. One time two of the girls spent a day at the Wilsons’ home, cleaning house, cooking dinner and giving every member of the family a bath, or making sure that he had one.

But the real tragedy of the Wilsons was not felt until Stella [Stella Taylor, of Community Girl’s Group] went to do her bit of service. Stella lives farther down Big Laurel, close to Turkey Fork. As neighbors, she knew the Wilsons very well. As Pine Mountain student and social worker, she saw a different side of their problem — the mountain problem intensified and exaggerated.

Stella came with tears to the office to say that the Wilsons must be helped in the name of God and humanity. That was the beginning of the Wilson exodus from the very bottom rung of the social ladder. Joe was given the job of fireman and farm worker on our grounds and a house was found for the family fairly close to the school where P.M. [Pine Mountain Settlement School] could keep a paternal eye on their comings and goings. They moved into the old Nolan house, across the road from the spot where the post office used to stand — when Pine Mountain School began upstairs [in the Nolan house in 1913], nearly thirty years ago. It was a poor shack at best and leaked in rainy weather, but a palace compared with what they had been used to. Joe stopped in the office to sing the praises of the school, and particularly of Mr. Morris [Glyn Morris] and Mrs. Morris, who he said were just like a ‘mammy’ and a ‘pappy’ to him.

“Nick Pennington farm from West Wind Hill.” Former Nolan house,c. early 1940’s. [bishop_11_005.jpg]

Insured [?] by twelve dollars and half a week, a portion of which was deducted and put in the safe at the school to be saved for a rainy day, for, of course, the Wilsons had no thought of planning and knew nothing about what to do with money. ‘Thias [Mathias] had a job in the school laundry, Bessie worked for Mrs. Columbus Creech, and all in all, they did pretty well. Mrs. Wilson used to come to the school with apples for her favorites and invited us to dinner and to holiness meetings where Joe preached sometimes and they both danced and spoke in unknown tongues [“speaking in tongues”] — life was really good to them.

But came the war, The coal industry in Harlan which had been slack for years suddenly began to boom, and for months we heard of fabulous wages and plentiful jobs just across the mountain. Our night watchman left, our coal miners left — and finally, old Joe said that he was going to “sign” also. He was distraught and absent-minded — fires were badly tended; he was unable as he said to “cooperate with the management” — At last, he was determined to go.

I had put my name on the list to accompany the truck to Harlan on a given day and learned a few days before that the truck would be moving the Wilsons so that if I wanted to go at some future time when I’d be more comfortable, that could be arranged. I thought I’d be delighted to help move the Wilsons if they had room for me. Brit [Brit Wilder] said no question about that because they always had plenty of room.

When the morning came it followed a sleet storm, and we awakened to a new world, coated with ice, every little branchlet of every little tree glorified, shimmering. One was shocked by so much beauty, so lavishly displayed and I thought with embarrassment for mankind and the things he is proud of, — the glass flowers in the cases at Harvard University, tenderly buried underground in case of fire — when here was this inimitable glory, a thousand miles from anywhere at all, blooming for a day, and careless of existence.

I slipped and slid over the cinder path to the office, to see what was going to be done about the trip over the mountain. Brit [was …? …?] said certainly he would go and hadn’t he been up since four o’clock out to the Wilsons, loading their house plunder on the truck.

“Well,” said I, “Do you think it’s safe, Brit?”

Brit smiled cheerfully — and when he smiles he smiles all over — and said “No. I wouldn’t go so far as to say hit was safe, but you cain’t tell about that till you try, and if you cain’t do it you cain’t. That’s a fact.”

I said dubiously, “I suppose a tailspin over a cliff would be conclusive proof that you couldn’t” and he agreed that hit would be. He also added that with all that plunder on top it would cut quite a shine if she got started skidding backwards. So I decided to take a chance. We picked up our burdens and started tramping the quarter of a mile to the Wilsons, meeting Mr. Anderson [Chris Anderson] along the way. He shouted across Greasy, “Startin’ for town?” Brit allowed we was. Mr. Anderson assured us we’d never make it “Countin’ on you folks comin’ back,” said he, and Brit said we’d be lively corpses he reckoned.

Page 3 [cobb_migration_003.jpg]

We passed on the road countless fir trees bent double under the weight of their load of ice. “See them leetle fellers, all stooped over,” Brit said. “If they was to come a suddent blow them’ll crack like a match. You want to watch out and don’t walk underneath them down hangin’ trees if you kin help hit.”

After Chris Anderson, we saw not a soul until we rounded the bend and started up the incline toward the Wilsons’ house. It was quiet there, and there was, we could see, smoke coming from the chimney, but the silence seemed to speak of departure, prophesy loneliness and emptiness. We could just see through the foliage our truck which Brit had driven up the narrow alley way close to the house. It was piled as high again as the truck bed, itself, with a motley [?], the most of which we could discern from the bottom of the hill being a linoleum carpet and the corner of a set of bed springs.

View down the Pine Mountain valley from Infirmary to Incline with snow. [kingman_034c.jpg]

Joe lumbered out next. He is so tall that he looks as though spirit and energy and intellect just never managed to catch up with the top of his head. He stood in the doorway a second, stooping to keep from hitting the sill, and bowed gravely, without removing his tattered hat. I remembered that I had never seen Joe in all these years, inside or out, without his hat.

“May the Lord bless you,” he said with grave courtesy. Then he lurched forward, pushed along by Mrs. Wilson, a little nervous woman, who must have been quite a beauty before she lost her teeth and had so many children. She was much worried and flustered but tried to be cheerful, alternately smiling and bowing and making proper conversation with me, and barking sharply at the boys.

Then ‘Thias and Albert came out, and two of the neighbor boys, and [then] Bithy [Tabitha] and little George respectfully [….?? handwritten correction, truncated]. ‘Thias was rather inclined to stand around and wait to see what would happen, but his mother pushed them all nervously ahead of her through the snow and ice. “Get a pan of water, ‘Thias — Mr. Wilder is wantin’ a pan of water. Go catch the pigeons, Bithy. Bessie, says she cain’t live and stand it without them pigeons. Don’t try to hold the dog, honey (this to Harmon). You’s too little. ‘Thias take that dog. Hit’s too little to hold a dog. (Then to me) Law, Miss Cobbs, come in where they’s a fire. No’m we hain’t had no breakfast. The younguns tuck the stove down last night, and they warn’t no way o’ cookin’ — seem like I cain’t cook over grates [fireplace] like I used to when I lived with ma. (To Joe) Go along ther, and pull that hemlock outa t’road. Cain’t nobody with a truck o’ plunder get in under all that.”

By hook or crook we caught the pigeons, held the cat and dog, tied on the carpet and two chairs, pulled a galvanized bucket from the very bottom of the piled up truck so we could fill the radiator up with water, and found nests in the piled up plunder where the little ones could ride, all covered over with mattress and two threadbare pieces of cloth carpet. It was to be a cold ride at best. Harmon had no coat, only his overalls and a thin little sweater and no hat. George had a cotton backing raincoat, but no sweater underneath, only his worn cotton shirt. Bithy did better with an old astrickan [?] coat, and Mrs. Wilson was resplendent in a moth-eaten fur, which had come from the Pine Mountain office attic two years before. She is unwell, looks to be expectant again, and had a cold, as did all the others in the family, and I insisted that she ride in the front seat —- as we started off — four crowded into the small front seat of the truck and fairly packed, even under the steering wheel, which Brit managed from an awkward position half inside and half out the window. Mrs. Wilson sat forward and I sat back to give more room for the gear shift rod, and so I spent most of the riding time with my nose buried willy-nilly in the great collar of her coat breathing in…

Page 4 [cobb_migration_004.jpg]

…woodsmoke, greasy aroma from months of cooking, and goodness knows how many milions of varieties of germs.

We finally got lodged somewhere and started backing in slithering fashion, I thankful for our double chains, down the incline. Then it appeared that we couldn’t get by between the chicken house and a fence post which stuck out on the other side. So we all got out and stood around on one foot and on the other while ‘Thias [got out ?] hunted a plank to prize out the post and a spade and pick to dig a hole farther back to put it in. Then we piled back in again and got ourselves packed away, started slithering backward again, and the next moment had to stop because the motor wouldn’t start and the breaks might not hold with it so slick. Joe cranked and we all got out to take some of the weight out and, finally, it got started, but I decided not to get back in until we were safely at the bottom of that incline. It was a wise decision because a few feet farther on it was found that Joe hadn’t got enough of the hemlock out of the way, and we had to wait while the boys got a hatchet and cut away the boughs which hung in the path of the linoleum carpet, which stuck out awkwardly from the top of the plunder.

Truck loading crop. VII 64_life_work_019a

At last we were off the incline and on the road — that is the truck was — and we all patiently fitted ourselves back together again. I saw Joe tuck the tattered end of an old gunny sack around Harmon’s chin, and then perch himself on the bedstead which stood up an inch or two out of the general mess, so that he could sit on it and lean against the back window of the truck seat. Bithy’s brown eyes danced from the depths of the center somewhere, and she held carefully an oatmeal box containing a half dozen eggs, gathered just before we left because they couldn’t take the chickens, and had willed them to Nick Pennington. The oatmeal box rose aloft from her fingers midway between two legs of the kitchen table, turned upside down, so that it had rather the appearance of an oblation at an altar. ‘Thias and Albert sat on the very back end, high on top, swinging their legs, and blowing on bare hands to make them warmer. I trembled for their heads when we should pass under the “leetle stooped over” trees which line the mountain road, but trusted them to take care of themselves. George I never did see, but some soft little snuffle from down in a corner, in the space where we had pulled out the galvanized bucket, made me believe that he had successfully buried himself.

Then I climbed in, next to the Co-op [Cooperative Store] shopper who had a huge carton of soap to hold, to which I added my slide projector and Miss Fenn‘s radio which she had made me promise to hold in our own hands and we all heaved and pushed, and Mrs. Wilson got in, fur collar and all — from that moment my view of that side of the world was nil — I could twist my neck and see with the other eye out of one side of the window, and enough to be dazzled by the unearthly beauty through which we presently began to move — deliberately, ponderously, but nonetheless moving — up, up, and up, sometimes heaving over to the side close to the embankment, more often perilously close to the sheer edge, so that my left eye could look down through miles of mist, into dim dark treetops, clustered in the canyon beneath.

[Hand-written note on left side of transcript: “She was a pahpetic [?] a bird the weather. ??]

“Lor!” breathed Mrs. Wilson after we were started. “We liked to of never got started! A body couldn’t noways tell hit would be like this today — and last week plumb like spring.”

John Hayes, Fern Hall, Bill Hayes, PMSS former students in Harlan, c. 1940. [hay0126.jpg]

She talked fast, with anxiety. I had the feeling that this moving was not to her liking, She was a country woman, and terrified of the town. There was a wistful, desperate, frightened look about her eyes which troubled me. But she was the lady in spite of all — careful to be courteous, gentle.

Page 5 [cobb_migration_005.jpg]

I did see her turn a wistful Lot’s wife backward look to where the old house stood high on its incline, wisps of smoke still curling from the chimney, and a chicken resting on the top step of the porch — but a house so lonely that it seemed already full of ghosts of the Wilson brood, bound for the metropolis, leaving the country behind.

Brit kept us cheered with a philosophical monologue. “How I do like a day like this!” said he. “Hit’s like having a piece of old tough meat all of a sudden one day, stead of somethin’ easy and tender like you been used to having. Makes you appreciate the good days.”

At the foot of the mountain, we came upon a gang of men headed up by CC [Columbus Creech] working on the road. They all stopped shoveling and stood leaning on the handles of their shovels until we came up close. “Reckon you hain’t planning on getting across,” Columbus remarked by way of conversation. “Reckon we sure be,” Brit replied cheerfully. “Well, you best get yourself two good axes, I reckon.” Columbus chewed calmly a piece of twig or straw. “Buddy you shore hain’t going to get by without hitting a tree somewhere.”

We went on, but Brit was plainly a little worried, “Reckon we should’ve brung an axe at that,” he said partly under his breath. “You mean we might have to cut something down?” I asked. “Might could be,” he said. “With all them trees a stoopin’ hain’t no more nor likely they’ll be one plumb broke off. Well,” he brightened, “a body’s got no place a borryin’ troubles. They’s trouble enough without huntin’ around to find some more.”

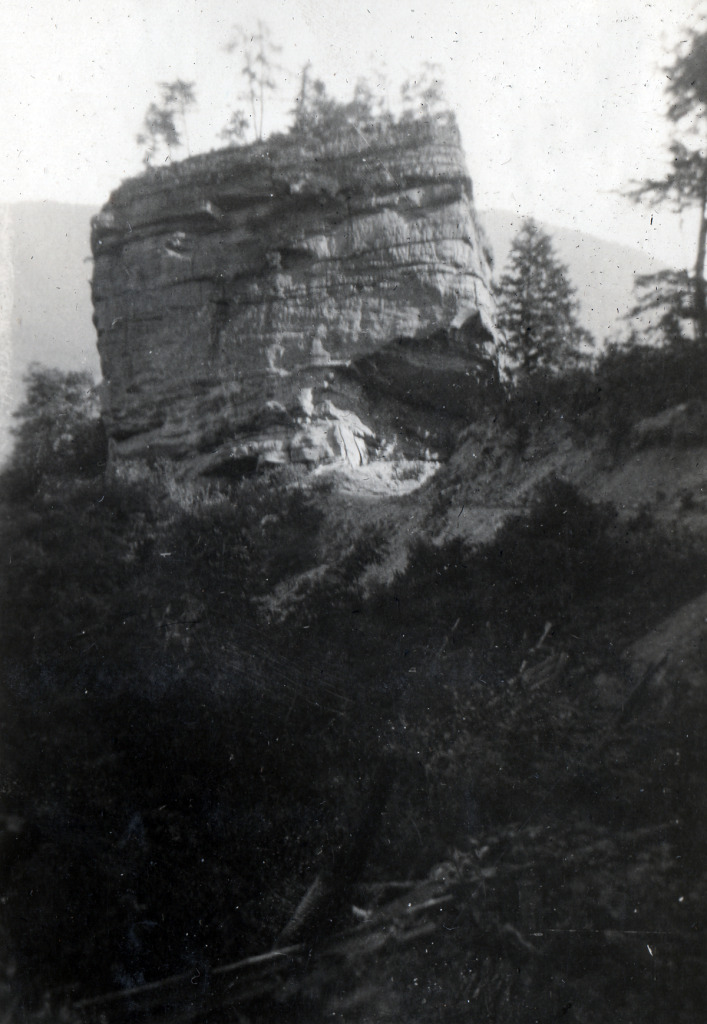

Maya Sudo Album: Rebel’s Rock with Laden Trail running under cliff. [sudo_album_037b_mod.jpg]

We were all silent for a moment or two. Even Brit was shaken. “Reckon we had ought to of brung a axe,” he observed. “Reckon you got a axe in the plunder?” he asked of Mrs. Wilson. She allowed there was one, but hit was that [so] dull she didn’t reckon hit would cut a splinter, much less a tree.”

They all piled out, to go look at the tree and figure the prospects. I didn’t get out because I figured I could sit and look at that gorgeous cavern shimmering beneath us for a long, long time. It was nice too to breathe without breathing in wood smoke. They were a long time finding the axe and, in the meantime, Brit sent ‘Thias and Albert skuttling down through the woods, by way of the short cuts to bring two axes from the school tool house. Then he and Joe ambled slowly up to the impediment, took the measurements, pondered over the chances for removing it, studied the situation from above, below, in front, behind — and finally after a quarter of an hour of consideration and deliberation, hands grabbed the axe handle, and swung.

Mrs. Wilson was silent, obviously worried about the children, and I was fascinated — we sat without speaking for a long time, watching the axe swing high, hearing the far-off thud — it sounded far off because it came to us through the full misty air. We heard rustling and stirring from outside above, and presently crunch footsteps — little Harmon had climbed down and was peering in the window.

“Why’nt you stay wropped up?,” demanded Mrs. Wilson. “Go back there or I’m aimin’ to whup ye.” He paid no attention, but stood blue and chattering on the running board. “Come in here, honey,” she said with a quick change of tone, “I declare, you’re plumb froze to death.”

With infinite gentleness, she took the little one on her lap and folded him in her arms. He settled down without a word, against her pre […]. His eyes dropped shut under heavy curling lashes and in two minutes he was snoring, softly coughing and sneezing a bit at the same time. I thought…

Page 6 [cobb_migration_006.jpg]

…it was one of those beautiful pictures, which so often we see here in the mountains and which so few artists paint — this mountain madonna, worn, but beautiful in her tenderness, and this lovely child. Mr. Morris [Glyn Morris] has so often said “We must sometime, somehow write a book which will really show the overtones, the beauty and pathos, the sadness and joy, the childishness and maturity, the light and shadow of the mountains.” And I felt that what he felt was here too, at that moment.

I heard crunching footsteps behind, and presently Art Boggs appeared. His truck had stopped just behind us. He went on up to the tree, and the three stopped to confer for several moments. Then Art stepped back, Joe picked up the axe, and the swinging and thudding started once more. This time they were cutting away one of the great limbs which propped up the tree trunk. Presently it broke under the axe and, with a little rushing crash, the whole tree fell forward, caught by the second huge limb, which now braced it in the air. Now two more men and a young boy climbed up from the high cut below to join the group. By the time the second little crash came and the great tree pushed on farther down, so that it rested on its own trunk. The mailman from Putney drove up on the other side and pulled a sharp saw. He seemed to have a crowd with him, for the mailman (against the law) runs a sort of informal friendly taxi service across the mountain. They began to pile out one by one, and then I noticed two gentlemen sitting on the back of the truck, dressed immaculately, as I thought through the mist, in white collar and rakish-looking dark blue hats. I thought perhaps it might be the two photographers from Look Magazine who were expected that day or the next, and thought they had come at the right time and in the right way to have something to write about. [Handwritten note: “It turned out later to be Bill Coots and his brother Harrison on their way to do business at Big Laurel.”] The photographers when they turned up were Khan and [….?].

At my side I could hear the heavy breathing of the little boy, and feel the weight of the anxious brooding look his mother bent upon him — his cold was so bad! Above and below I could hear crashing and crackling as limbs broke with the weight and came tumbling down, hundreds of little ice avalanches, and in the distance the dull thud of the steadily ringing axe blows. I suppose an hour passed, and I was nearly asleep myself. Anyway I missed seeing the moment of triumph, but I heard it. The whole valley echoed with the crash and the cheers, and dozens of extra avalanches crashed down toward us from above — the great tree went sliding with a rush and roar straight down into the canyon. In a second or two there was silence, an echo, and then no sound. Even the man who had done the job stood silent. We had seemed for a few minutes in eternity — and now life began again. Quickly as they had come, the little crowd which had collected vanished, below, above, and by way of the shortcuts. The two boys who had gone back for sharp axes appeared, surprised but not disappointed that their trip had been in vain.

We all fitted in again. Baby Harmon was loath to hunt his nest under the gunny sack, and Mrs. Wilson pushed him crossly from her lap, bidding his father, “Wrop him up now.” I sighed and took a long breath of good fresh air, knowing it would be the last before Harlan, which is never fresh. The motor started. We skidded, heaved, and righted our selves, and were off.

“I declar,” observed our Brit, “That there were fun!”

I said there were times when I thought we could hardly run this world if it weren’t for the men. And Brit said “Well you know Miss Cobbs, I were just thinking’ that very same kind of a thing, only I were a thinkin’ it about the woman. Sometimes when I come in of a evenin’ all tired out with working, and there everything is so nice, and a nice good dinner smokin’ on the table, I just thinks to myself hit takes a woman to make the world just right!”

Page 7 [cobb_migration_007.jpg]

Except for this burst of enthusiasm and philosophy, the rest of our trip was rather silent. Mrs. Wilson hardly said a word. It was plain that she was more worried by the moment. She must have sensed what we knew, the implications of this move for the little brood. I found myself sharing her terror for them.

Joe, I knew, might have a job, or he might not, when he got right down to it. And if he did make some money it was two to one he would never get home to his family with it. Poor Joe simply has not the average person’s amount of sense and judgment. I had visions of his falling from grace in the city, losing his temper and being hauled into jail (Joe has been a killer, days gone by). I saw poor little red-haired Bessie, clerking in a tavern in the town. She is rather a pretty child, and quite unprepared for the temptations of a mountain metropolis [a town like Harlan]. Their very address now — Bailey Hill — the worst slum in the Harlan area — warned one of disaster. It could not be very long before ‘Thias and Albert would take up with the wrong crowd of boys, and be led to law breaking. I saw them all shouting and singing at the Holiness church and going rapidly to ruin.

There is no stabilizing influence for a family like the Wilsons. There is no protection. In a dim way, I felt that Mrs. Wilson realized this, and saw their leaving the paternal eye of the school as a disaster, which she was powerless to prevent. Caught in the wheels of the machine age, one more helpless little crowd of victims would be pulled into the teeth of the mill.

At Harlan, I left them. I stood on the sidewalk waving goodbye, telling them to come back and visit, promising to visit them myself, and they waved back from the window, from behind the mattress springs, and the table legs, and the roll of carpet. The big truck heaved around a bend toward Bailey Hill. In beauty and terror, the Wilsons had migrated.

GALLERY: ALICE COBB STORIES Migration From Hinterlands to Industrial Area c.1940

- cobb_migration_001

- cobb_migration_002

- cobb_migration_003

- cobb_migration_004

- cobb_migration_005

- cobb_migration_006

- cobb_migration_007

Return To:

ALICE COBB GUIDE to Writings, Collected Stories

See Also:

ALICE COBB Staff Trustee Biography