Pine Mountain Settlement School

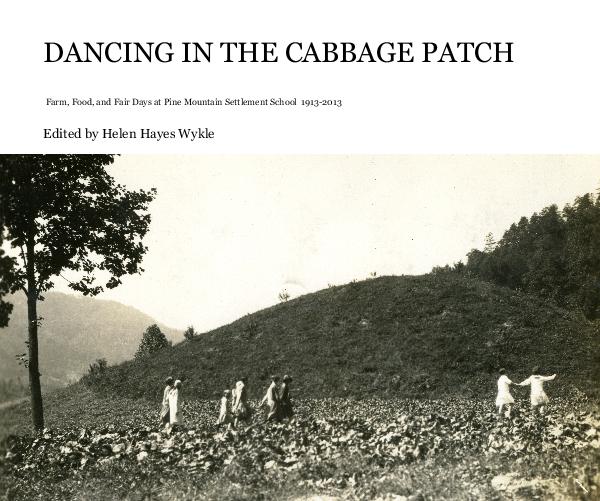

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH

Pine Mountain Settlement School as Place

and the Physical Space of an Idea

LOG CABIN

Poem by Dora Read Goodale (1863-1953), from Mountain Dooryards, Torch Press, Cedar Rapids, IA, 1941.

Little bitty ……. hit mought so be,

But it doesn’t look that way to me;

Ever’ log in it once a tree

That aimed at the sky ; the chimley-herth

Once a piece of the living yerth

And old Kentuck; and shutter and sill,

Puncheons, ruf-boards, or what ye will

Hewed and rived by my pap’s pap

When he was young an full of sap

Ther’es Coy’s fiddle — I tell you what! —

Mammy’s churn, and the big black pot

For Monday’s wash; and the shot-gun thar

Over the door, that’s kilt a bar;

Porch out front, and a picket gate

With flowers a-blowin early and late —

Why, ever’ one of em’s dear, so dear,

If I’d done been in Heaven a year

I’d still want out, to get back here.

Dora Read Goodale

Dora Read Goodale came to Pine Mountain Settlement School to teach when she was forty-seven years old. She was born in 1866 in Mount Washington in the Berkshires. Her arrival at the school in the founding year of 1913 provided her with a unique perspective of the school and community. She came from a precocious Vermont family of writers and poets and brought those talents to her teaching at the school. Before she had reached adolescence she and her sister, Elaine Goodale [Eastman] had published extensively in national magazines and journals. and Dora, the younger of the two, continued writing poetry for most of her lifetime. Her last work at age 75 was Mountain Dooryards compiled while she was in residence at Pleasant Hill mission school, a Tennessee school, not unlike Pine Mountain. She served as the director of the Uplands Sanatorium in the late 1930s through 1941, a treatment center that was part of Pleasant Hill mission school.

The 1920s view of the Settlement School reveals the cleared areas and the site of the institution within the steep mountainous terrain. The wide-angle view is deceptive, as the closeness of the mountain is missed in this panoramic view. Lower left is Old Log, the oldest building on the site. The Tool Shed is to the middle left and the Office sits to its right. Deep in the valley is the Burkham School House II and to its right is Old Laurel House. The Barn sits high on the hill above the Office. The Infirmary (now Hill House), Practice House, and Farm House were not yet built, nor were the Swimming Pool and the Draper Industrial Building. Big Log is hidden in the middle distance of the photograph. The Chapel is to the far right side and beyond, hidden by the dark knoll is Far House I. What stands out in this photograph is the large swaths of cultivated farmland.

Aerial view of Pine Mountain Settlement School c. 1941. Westwind is just under construction as the white patch to the right of the photograph. Again, cultivated fields stand out against the heavily forested area around the school. Today, most of the fields are overgrown with young timber and the cultivated land has been reduced to the central areas of the campus at the middle of the photograph. Photo, Arthur Dodd.

Pine Mountain Settlement School is nestled in the long valley on the north side of the Pine Mountain, a long continuous mountain chain on the Cumberland Plateau in the Southeastern United States.

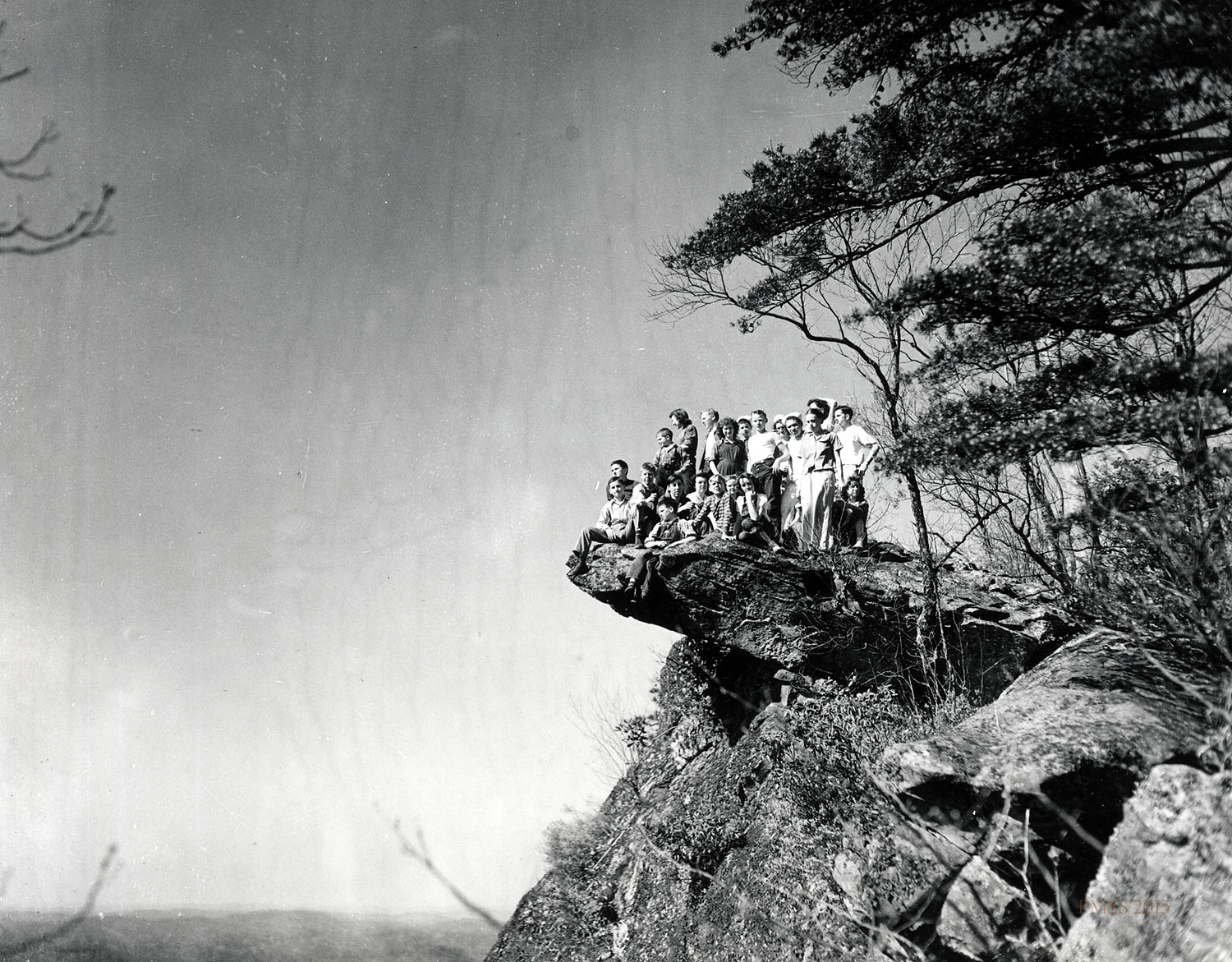

View down the Pine Mountain valley from the Westwind hill. c. 1920s.

The Cumberland Plateau encompasses some ten thousand square miles and contains nearly twenty counties in the eastern corner of Kentucky. Pine Mountain Settlement School is in Harlan County, in the far southeast corner of the state where it borders on Virginia and Tennessee. The mountains in this area represent the most majestic in the state, particularly Big Black Mountain which faces the Pine Mountain range on its South side.

Harlan County was named for Major Silas Harlan, a commander in the Illinois Campaigns of 1779, and was the sixtieth county added to the state. It was formed from parts of Knox and Floyd counties. The county was one of the highest, most mountainous, and most remote of the state’s 124 counties at the time of its formation and it remains remote in many ways, even today.

The history of Harlan County is dominated by a history of coal. Most all the mountains in the region contain coal that was formed when the ancient bog and vegetation of an inland sea was compressed into peat and then into coal over a period of millions of years. Pine Mountain, one of the mountain chains formed when the earth buckled and thrust upward has coal but is not coal-rich as the coal seams are too difficult to mine. due to their quasi-vertical angle. This long “thrust-fault” mountain chain, some 150 miles long, parallels the tall Cumberland range to the south which is certainly coal-rich. Within this range is the “Big Black” mountain, at 3,300 feet, the highest mountain in the state.

When the Pine Mountain chain was formed, it thrust upward along the 150 miles in a continuous line running east to west. Pine Mountain Settlement School sits on the north side of this east-west thrust-fault and below the watershed point on the mountain for two rivers, the Kentucky and the Cumberland.

An amusing story is told of a local community member who had a unique perspective regarding how the mountain could have come to be so tilted. He asked Alice Cobb, a school worker, if she knew, “Why Pine Mountain was such a “quare” shape with so many big loose rocks scattered around.” Miss Cobb started to respond with her short interpretation of the geology of a “thrust-fault” when the man continued. “Well people about here thinks that when Christ was crucified the earth trembled and shook so it knocked Pine Mountain plum over on its side. And, that’s why.” And, “on it’s side,” it is. It is the gentle side, the slope, that forms the backdrop to the Settlement School though the mountains sit so close together, that the long slope is pressed up against everyone who lives in the valley.

As streams pushed their way through the early plateau, they created multiple steep valleys with meandering creeks and rivers. These many waterways eventually wound their way as large tributaries to the Missouri and the Mississippi further west. Harlan County and specifically the Pine Mountain range above the settlement school is the source of three of Kentucky’s major rivers; the Cumberland, the Kentucky and further north, the Big Sandy river.

The Cumberland River runs westward and southward through the length of Harlan county and has its head-waters on the south-side of the Pine Mountain range. Isaac’s Creek or Isaac’s Run, which runs through the campus of the School is the essential headwater of the Kentucky River as it begins its journey.This stream on the north side of the Pine Mountain range soon forms Greasy Creek and then joins the Middle Fork of the Kentucky and then on to the main Kentucky river.

State historian, Thomas D. Clark, told the story of this important state tributary in 1942, in a book titled, The Kentucky. Clark asked John A. Spelman, III, an art teacher at Pine Mountain Settlement School, to illustrate the book with his linoleum block prints. The Kentucky was one in a series of books written for The Rivers of America Books, edited by Stephen Vincent Benet and Carl Cramer. The Kentucky remains the definitive work on this beautiful river and a rich source for information on rivers and culture in the eastern part of Kentucky. Pine Mountain retains many Spelman original blocks that echo the rich work he completed for this important book. Over 100 wood, linoleum and metal engravings capture the unique style of the talented artist. Many linoleum block prints of John A. Spelman III are found throughout Pine Mountain school publications created in the late 1930’s and the early 1940’s.

Author Thomas D. Clark says of the Middle Fork of the Kentucky

“… the middle one [stream] scampers along through the Big Laurel to Greasy Creek and then to an arbitrary point where temperamental map makers finally decide to imprint the name “Kentucky.” Perhaps nowhere else in America does a stream drain a more genuinely rural or isolated area. In some respects, the valley of this fork comprises America’s human museum. Here the great westward movement eddied and then stood still. If it be true, as some sociologists have assured us, here are to be found America’s “contemporary ancestors.” Human life has changed little from what it was when the first settlers forced their way through the great pass at Pound Gap or wandered upstream from the “three forks.” [Clark, p.9-10]

While Clark’s narrative written in 1942, captured life along the creeks of the north side of Pine Mountain, and a familiar refrain that has been echoed by many writers of the region, Spelman’s block prints capture the visual romantic wildness of the mountains in the area.

Spelman left another remarkable set of prints in which he captured the elegance of mountain cabins and the patterns of the mountain farm in his published work, At Home in the Hills: Glimpses of Harlan County, Kentucky Through the Media of the Linoleum Block and the Woodcut. Published in the Pine Mountain Print Shop in 1939, it was this sensitive work that caught the attention of Thomas Clark when he went looking for an illustrator for his classic, The Kentucky.

Spelman says in his introduction to At Home in the Hills

Where else can one find houses that so grow out of the soil, chimneys with so much unconscious beauty in their lines, roofs and wall spaces with such “at-oneness”? Time and the weather have done much toward their decay, but so have they colored these houses and barns to a mellowness that it makes them at one with the hills upon which they stand.

The Harlan County region has always been difficult to access and to assess. The remote geographic area saw only limited settlement in the early years of pioneer exploration as most families pushed on to the fertile Bluegrass region. In fact the mountain area of Eastern Kentucky remained isolated far longer than many other more accessible areas of the Appalachian chain of mountains. This geographic isolation of the north side of Pine Mountain in Harlan County has been a point of discussion of all who have sought to study the area and even today it continues to challenge visitors as they are asked to assess their visits to the School or are asked “How do you get there?” Whether the isolation of the area brings to mind Shangrila or geographic determinism, it is a topic in most any discussion of Pine Mountain Settlement School.

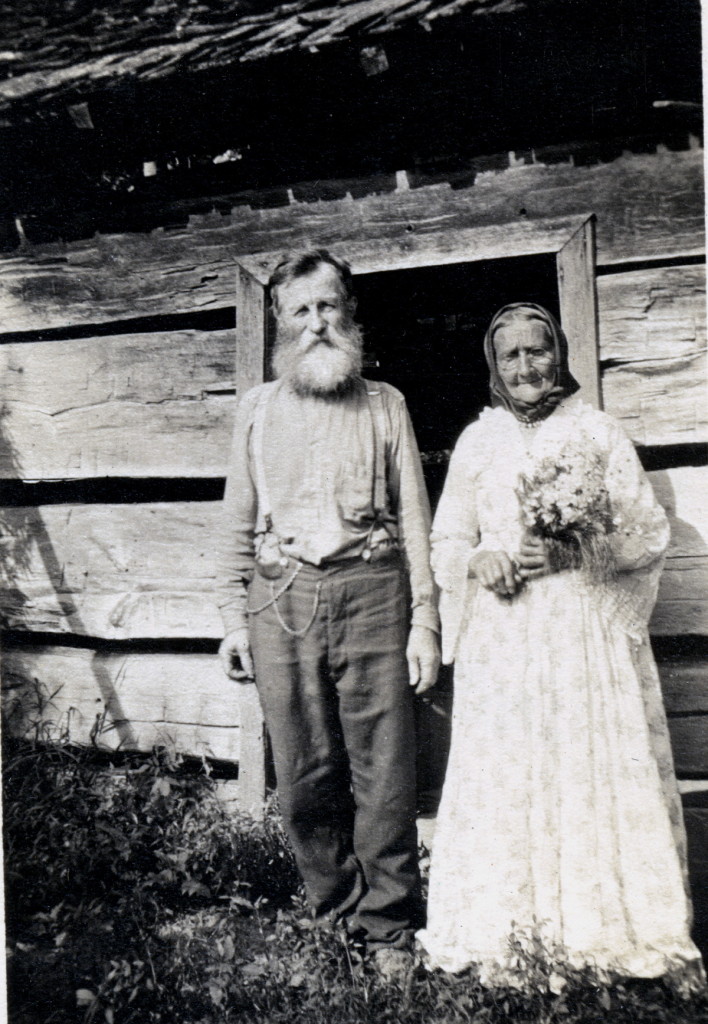

SETTLEMENT

Settlement of the region by pioneers, largely European in origin, came early in the nation’s history. The first exploration, completed by Dr. Thomas Walker in 1750, rapidly opened the area to hardy settlers. Immigrants mostly gleaned from England, Scotland, Ireland and the German Palatinate diaspora, eagerly homesteaded the mountainous area as pioneer farmers joining the Native Americans and a small number of African Americans who were found throughout the area.

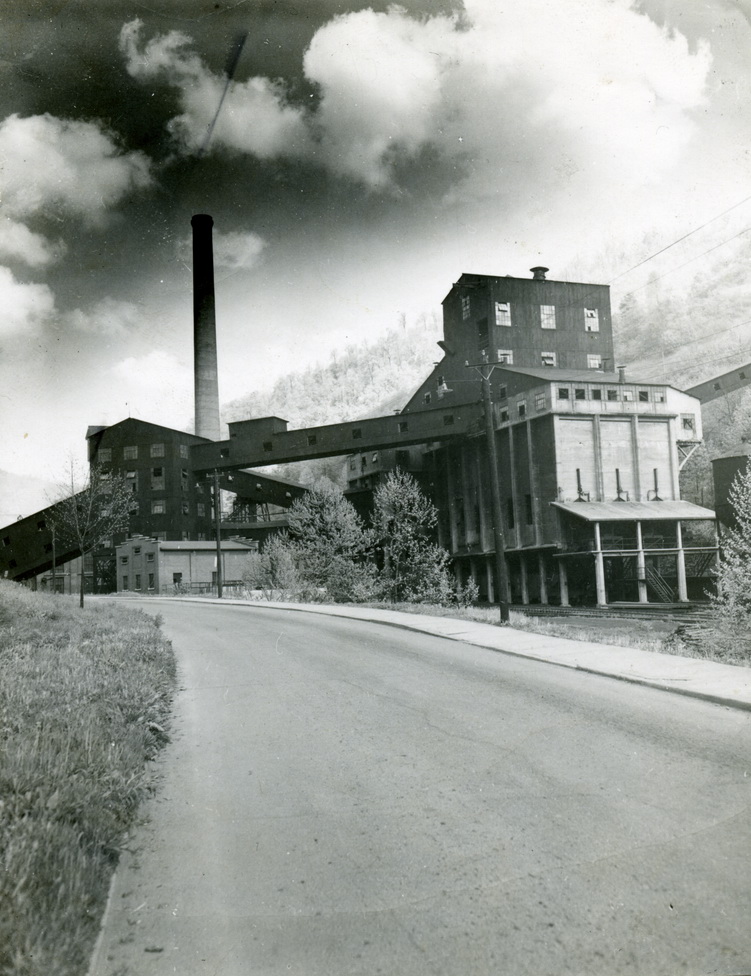

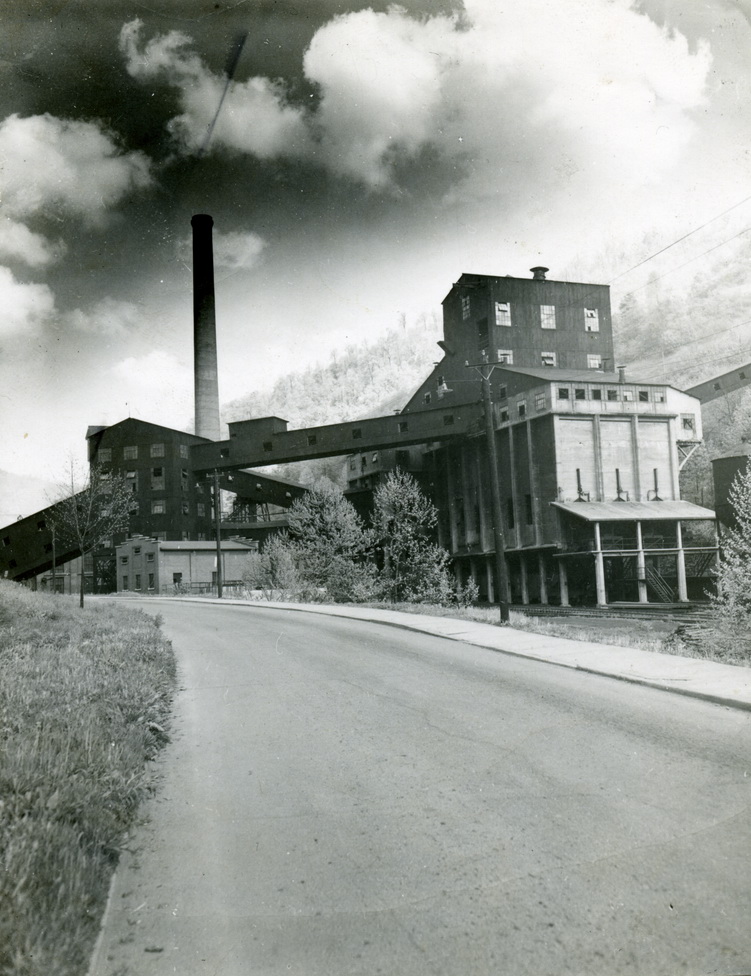

Coal Tipple, c. 1940. Arthur Dodd, photographer]

Coal Tipple, c. 1940. Arthur Dodd, photographer]

COAL

When coal was discovered in the mid-eighteen-hundreds, a wave of immigrants came from Europe and then Eastern Europe to work in the coal-fields. Italians, Austrians, Russians, Hungarians, Rumanians, Czechoslovakians and Polish men entered the mining work-force in Harlan County in large numbers. African Americans shifted from share-cropping and from inner-city life to join the coal mining labor force in many of the larger coal camps. Coal accounts for a large population of African Americans in Harlan County, particularly in the International Harvester and United States Steel mining camps of Benham and Lynch where the labor force was well paid and housing and schools were well supported.

While conditions were better in the larger coal camps, not all labor was equal. Kentucky’s eastern coalfields have been both a source of wealth and a deplorable example of labor exploitation. The region holds land of extraordinary resources and extraordinary environmental degradation. The history of the settlement school at Pine Mountain, found in its farming, foodways and festivals, a large and important theme for mountain living, but coal always runs as a sub-theme in all that was and is Harlan County from the mid-1920’s forward. King coal has often stood in contrast to, and sometimes challenged the environmental sensitivity of the School. This was particularly true in the opening years of surface mining. Today coal mining is both a significant monetary asset and a gross environmental liability for the region. The lack of a diversified economy throughout the Appalachian coalfields has always presented a land of competing values and contrasts.

Authors who have written about the region have all approached the quandary of coal from different perspectives. Dr. Thomas Walker in his important The Kentucky (1942) devotes one page to the topic. “Coal” does not show up at all in the index to Henry Shapiro’s Appalachia on Our Mind (1978), one of the most comprehensive overviews of the Appalachian region. David Whisnant, however, challenges the conundrums head-on in his All That is Native and Fine (1983). The two works reveal the gap that continues to perplex scholars as they confront the agrarian and industrial nature of the region. Whisnant engages the coal story and citations for coal-related subjects are many, including coalfields; coal industry; coal miners, etc.. Whisnant’s book recounts one of many conflicting stories of coal and its role in the life of eastern Kentucky, but it is a perspective that resonates with some and rankles many but that remains important to the debates that surround the role of coal and coal camps in the development of the settlement schools of the region.

One story in the Whisnant book describes the early relationship of the coal industry with Hindman Settlement, Miss Pettit’s former home. He recounts that early in the history of Hindman Settlement School when Miss Pettit was still with the institution, the secretary, Miss Eve Newman, secured some $25,000 in preferred stock from the Elkhorn Fuel Company which over the years yielded a continuing revenue stream for the school. John C. Campbell in a letter to John C. Glenn of the Russell Sage Foundation in 1913 noted that less than a decade after the founding of Hindman Settlement School (1909) some 76% of the school’s endowment was stocks and contributions from the local coal companies. While this large investment in coal stocks was an early revenue stream for Hindman, Pine Mountain found it difficult to establish similar early ties to coal.

Katherine Pettit, when she came to Pine Mountain, reluctantly pursued both coal companies and logging companies for donations but was rebuffed in her early attempts to wrestle donations from both coal and timber companies working in the local area. Her initial efforts to secure contributions from the Kentweva Coal and Lumber Company and its President, Mr. Merritt Wilson, were largely unsuccessful, as were her efforts to stop the Company from running a narrow-gauge rail line to haul virgin timber through the heart of her new campus to distant mills.

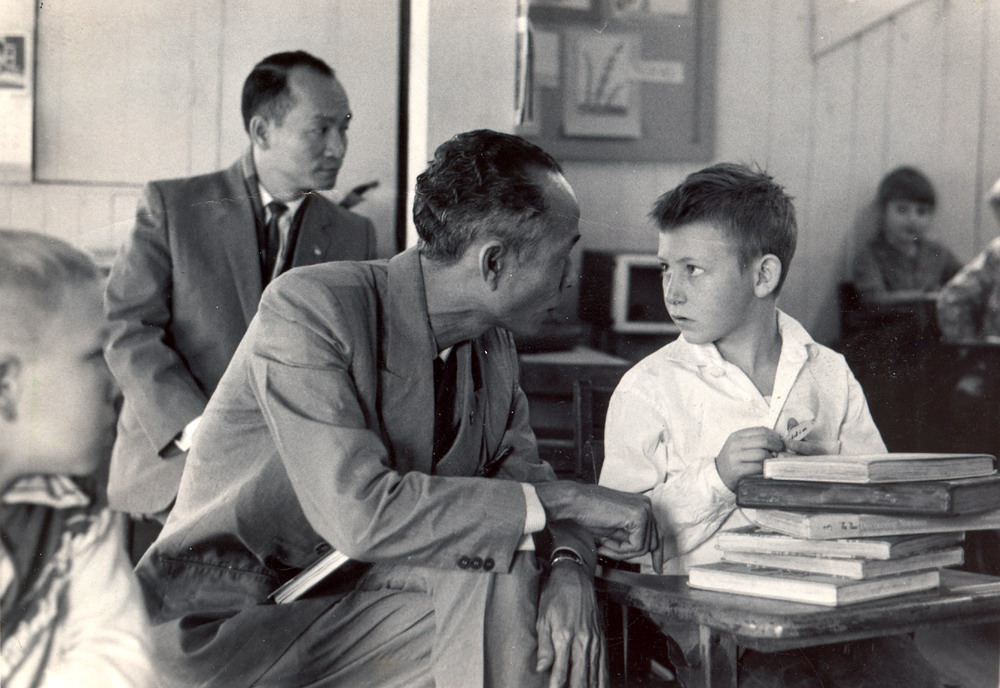

Ron Eller’s book, Miner’s, Mules, and Millhands (1986), a well researched classic resource on Appalachian life, also looks closely at coal and its impact on eastern Kentucky and other coal areas. It provides a balanced, documented, and clear assessment of the many sides of mining, mines, and miners. The story of coal and the Pine Mountain valley is a complicated one but the story of Pine Mountain Settlement School yields a history that largely placed the school outside the influence of the coal industry, but not its impact. Though the initial purchase of land for the school involved a land swap with the coal and lumber company, Kentweva, the competition for land and resources in the narrow valley has steadily waxed, waned, and waxed over many cycles at the School. Again, isolation played a key role as the north side of Pine Mountain has no coal and the area is too remote for much change. It is, as recorded in a Settlement School survey taken in the late 1930s, “Some Shifting Aspects of Our Problem,” that the School was “16 miles, 6 hours from [the] Railroad.” Further, it noted that the “mines produce a large shifting element that is perpetually on the move, and therefore a very difficult class to help.” This antipathy toward the populations of coal camps and mining communities shifted during the late 1930s and 1940’s when the need to help the youth from the large mining population centers became dramatic and youth from mining camps comprised a significant percentage of the School’s population.

For nearly half a century the school moved forward without significant contributions or endorsement from coal companies that came and went in the region. Dis-entangled from any financial relationship to coal, the school became a voice for individuals, organizations, and institutions that began to question the serious environmental issues associated with the coal industry. By the l970’s both the environment and the social fall-out of the coal industry became a national issue and when Johnson launched his “War on Poverty,” the coal region came under the scrutiny of not just the Nation, but of the whole world.

When Uncle William said that he wanted the School to be a lesson even for those in other lands, he would not have imagined what valuable lessons many of those would be. Over time, the school slowly became the conscience of the region with regard to mineral and gas extraction and the School began to openly oppose any entity that would damage the environment, the economic security of the region’s people, or the health of both land and the people. This vocal advocacy which continued from the 1970’s onward was seriously challenged in 2000 when it was clear that the coal industry was quickly beginning to encroach on the rights of the school and was showing little concern for its operational environment and its modeling of environmental education.

The encroaching surface mining in the area threatened the image of the school as an environmental center and threatened the pristine scenic views of the school, its watersheds, and its unique flora and fauna. Fearing an ever-growing coal appetite and a fledgling gas exploration and facing an expanding degradation of the environment, Pine Mountain took action and filed a petition on November 13, 2000, with the Kentucky Department for Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement to declare the surrounding 5,226 acres around the school as unsuitable for all types of coal mining operations. This so-called “Lands Unsuitable …” petition pointed out that the School had recently received status as a National Historic Landmark site and that as a national treasure it would suffer irreparable harm from continued mining in the immediate area.

Robin Lambert, Executive Director of Pine Mountain Settlement School (1999 – 2001), said

“As trustees for a National Historic Landmark which provides a unique resident outdoor environmental education experience to over 3,000 school children each year, and which has been a cultural and educational resource to this community for over 85 years, the Board of Trustees of the School believes that the permanent protection of the School property, the spring-fed water supply, and the view-shed, from mining impacts, must be our first priority.”

As reported by the Kentucky Resources Council, Lambert stated,

“The process for designating lands as unsuitable for mining was intended by Congress to protect those lands where simply mitigating mining impacts on the environment would not be enough.”

The 32-page petition, endorsed by the school’s Board of Trustees, with strong support from environmentalists, historians, and friends, was successful in its effort to curtail proximate mining and to protect both the environmental mission and the physical environment of the institution for future generations.

These actions were specific to the immediate threat to the institution and were not intended as an indictment of the responsible coal industry and the many labor benefits that responsible mining operations brought to the region. Many of Pine Mountain’s boarding school children and, later, the children within the community, had strong ties to coal mining and their families were often wholly dependent on the industry for their livelihood. The tensions of these conflicting interests can still be felt in the community, but the School pulled from these experiences one of its most important educational missions, that of raising awareness of the human impact upon the environment.

Today, strong ties to coal is still the reality in Harlan County and the surrounding region. Coal is “King” and “Black Gold” rules both the economy and the cultural mind-set of the region. But, as coal again turns its back on the people of the region and as the industry declines — some say its last decline — the people and the state are looking for other economically sustainable livelihoods.

It is the juggling of diverse perspectives, the commitment to civil response, and the environmental realism of Pine Mountain Settlement School that makes it so very important to regions such as eastern Kentucky that are being devoured by insensitive corporate interests and by equally insensitive personal greed. This ravenous appetite for mineral and other resources is now world-wide and the dangers to the environment and to people is great. Conflicting views arising from mineral extraction is an international reality that is being played out in nearly every corner of the world today as resources become scarce, and as industries lose their social compass and populations grow. Clearly, a strong environmental voice, education in our schools regarding our relationship and responsibility to vital resources such as land and water, and civic responsibility, is fundamental to everyone’s survival, not just those who live in eastern Kentucky. Learning how to live as a community of diverse interests but one that shares concern and respect for the common good is vital to the survival of us all.

William Creech reminded Pettit and de Long in his letters that he wanted the school to be a benefit not just to the community, to “their generations as yet unborn, but to the whole state and nation and to folks across the sea if they can get any benefit out of it.” Pine Mountain still has this international perspective and continues to bring residents from throughout the country to work in the environmental education programs at the school. Pine Mountain invites foreign visitors to the school to experience the beauty and peace of the valley, while taking from the visitors, their multiple world views. This has always been the history of the institution — that it both shares its lessons and learns from the lessons of others.

As the region continues its struggle with the dominant coal economy and consciousness, and now with the rapid decline of that industry — again — It is not only Pine Mountain School, but the many social, religious, and educational institutions in the area that are struggling with what James Still, noted Appalachian author, called “a handful of chaos.”

James Still used this phrase in his sensitive portrait of an Appalachian family in River of Earth (1940). Caught in the chaotic transition from a simple life close to the land, many families were challenged to sort out a largely agrarian life-style against all that an evolving industrial economy promised.

In Still’s novel the family obliquely debates their future as they roam in search of the eggs of a guinea fowl in the pennyrile near their home.

“This would make the finest hayfeed ever was,” Mother said. “Just going wasting.”

Father kicked the lush growth where it caught the top hooks of his brogan.

“I hain’t started eating grass yet,” he said.

“There’s not a beast on the place to be cutting it for, and it’s the truth.”……”If we had us a cow her udders would be tick-tight,” Mother said.

“It would be a sight the milk and butter we’d get.”

“Won’t have use for a cow at Blackjack,” Father said. “I hear the mines are going to open for shore. They’re stocking the storehouse, and it must be they got orders down from the big lakes. This time of year they come, if the’re coming a-tall.”

Mother picked up the baby, holding him stiffly in the crook of her elbow.

“Where is the big lakes standing?” Euly [their son] asked.

“A long way north. It’s on reckoning how far, ” Father said. “There’s ships riding the waters, hauling coal to somewheres farther on.”

“I had a notion of staying here,” Mother said, her voice small and tight. “I’m agin raising chaps in a coal camp. Allus getting lice and scratching the itch. I had a notion you’d walk of a day to the mine.”

“A far walking piece, a good two mile. Better to get a house in the camp.”

“Can’t move a garden, and growing victuals.”

“They’ll grow without watching. We’ll keep them picked and dug.”

“I allus had a mind to live on a hill, not sunk in a holler where the fog and dust is damping and blacking. I was raised to like a lonesome place. Can’t get used to a mess of womenfolks in and out, borrowing a dab and a pinch of this and that, never paying it back. Men tromping sut on the floors, forever talking brash.”

“Notions don’t fill your belly nor kivre your back.” [responded the Father]

Few authors have captured as starkly the lives of families caught up in the economic conflicts of the industrialization of eastern Kentucky, as does Still in this classic novel. The mining and timber exploitation of a region that was largely agrarian, fractured the lives of the rural families in the region. James Still heard their stories first-hand for he spent almost all his life within the folds of the hills of eastern Kentucky on Wolf Creek in Letcher County. He knew the lives of his neighbors and he heard their voices and sensed their dreams and he listened, closely. Very closely.

Land cleared for mountain subsistence farming.

Land cleared for mountain subsistence farming.

Pine Mountain continues to listen, as well. As Pine Mountain looks back on its one-hundred-year history it can take pride in its strong protection of the land; its commitment to the people of the region; and its understanding of the pragmatic life-style, the dreams and the work-ethic associated with labor close to the land.

Farming, food, community celebrations, and a strong commitment to the preservation and conservation of the natural resources of the southeastern Appalachians, eastern Kentucky, and Harlan County, are integral to the on-going ethos of Pine Mountain Settlement School. The activities associated with these core elements are part of the “educating for life” that continues to hold a fundamental place in its framework for the future. As the School has evolved and re-shaped itself to the twenty-first century and as it has adjusted to increasingly rapid cultural surges forward, it shows every evidence of doing so with a solid foundation and values just as solid.

As this narrative, Dancing in the Cabbage Patch, continues, it shares one story of Pine Mountain Settlement School. There are many. The essays are dialogues intended to contribute to and invite dialog regarding the most recent re-visioning processes at the School and more extensively in the eastern Kentucky region. The narrative seeks to show how re-invention and the processes associated with it pay homage to and derive strength from historical commitments. Like the warp of a loom, the narrative threads of history at the School continue to be a pragmatic and a demonstrably foundational dialog. The personal narratives continue as an unbroken warp within various communities of interest. The long narrative of the first one-hundred years is foundational to the next one-hundred. Farming, food, celebration and a profound environmental awareness are shared experiences that are understood at a very basic level by the institution and the community, even as that community continues to grow and change.

In its new form this electronic narrative looks to the past, but it also looks forward with hope that the guiding principles of the school, “… will make a bright and intelligent people …” as Uncle William hoped. Pine Mountain Settlement School is only one-hundred years down the road, but if the first century of the journey is any measure, the next many centuries will be even more exciting and rewarding if the values and the vision of all stake-holders can be shared and learned. It is ironic that coal sits as a fundamental contributor to the digital revolution. The coal-fired plant fueled the electronic frontier and continues to do so today. That Appalachia has been one of the last stops on that frontier, makes the coal relationship even more ironic. It seems fitting that Pine Mountain calls these inequities to our attention and that we remind the lords of industry that their empires were built on the backs and resources of this unique region.

Farming, food, various celebrations, and conscious environmentalism, still serve to help sustain the school and its community, but it is the people, seen in many of the images in this web, or more accurately, weft, that gives hope for the coming centuries. The resilience, determination, intelligence, and work ethic of the people in both the school and the community suggest that the future is bright and that the people of the valley of the Pine Mountain and beyond will continue to dance in the cabbage patch.

Just how Pine Mountain continues its commitment to community, how it protects and nurtures the land, how it expresses it joys and sorrows and how the people will respond to pressures outside the valley and the region, cannot be known. But, is is very likely that farming, food, health, celebrations, and environmental education will continue to be integral to the settlement school mission and to the lives of those living in surrounding as well as virtual communities of interest. It is also clear that those communities of interest are now, not just local, but are expanding rapidly to the global.

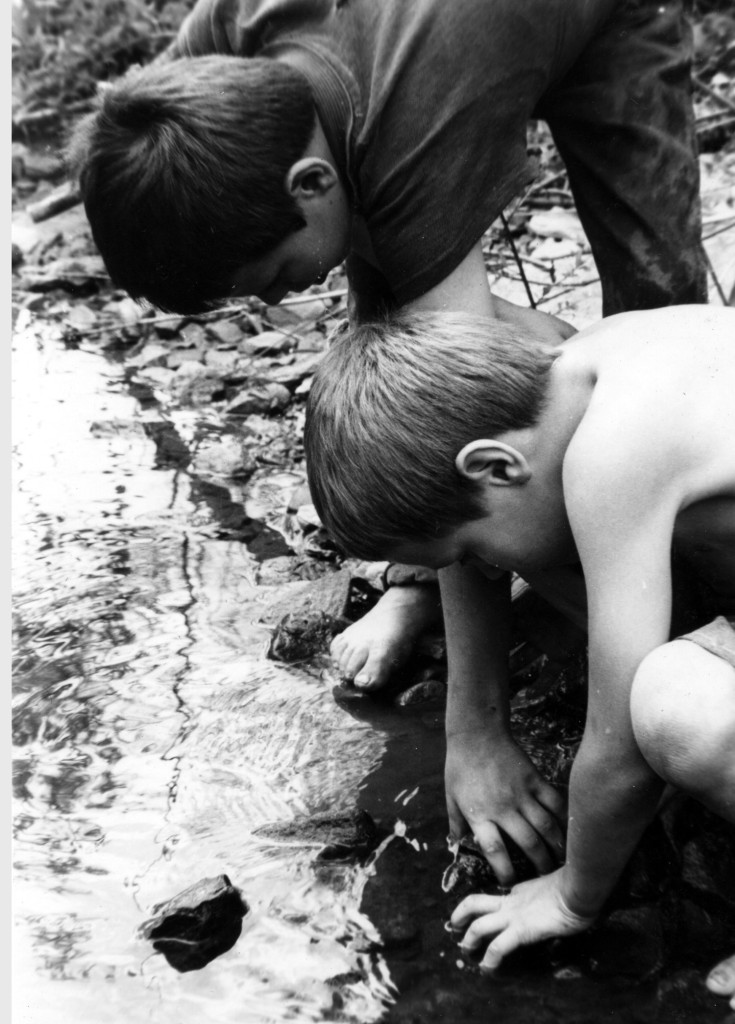

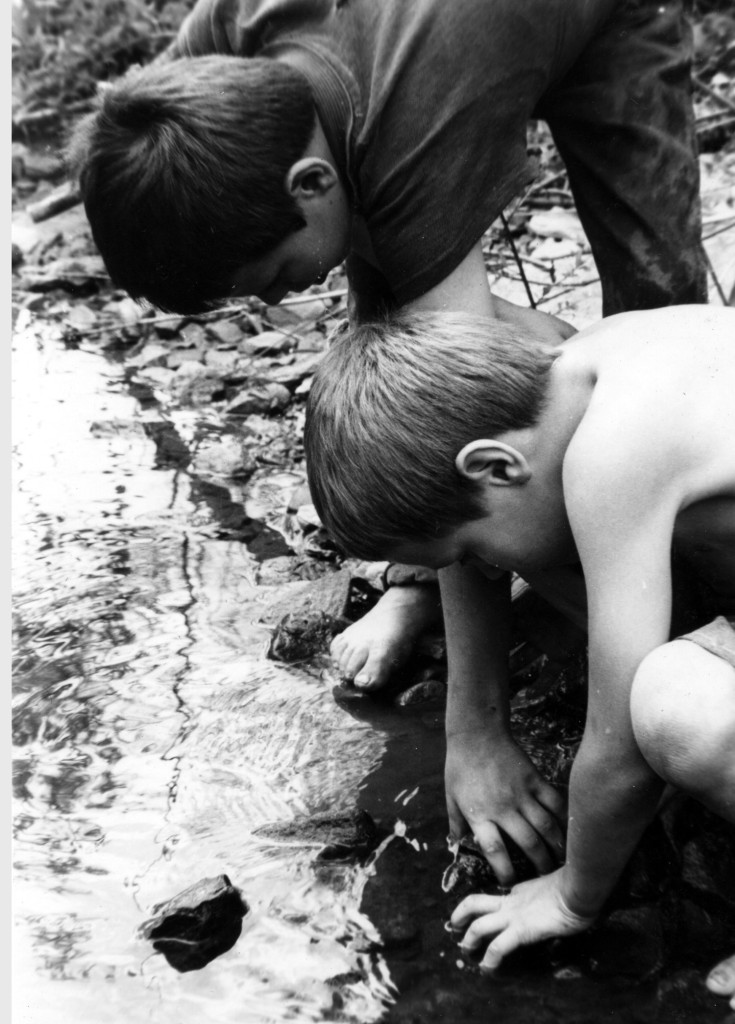

Capturing a snapping turtle, children at Big Laurel, 1960’s. Friends & Neighbors – VI-51 –

Farming, food, community celebrations, and conscious environmentalism have all become quite complicated by our modern life-styles, but as we all struggle to sort out how we will manage the “new-normal,” it may be instructive to look to the lessons found at Pine Mountain Settlement School and to imagine them practiced in a wider context.

Students participating in the Environmental Education program at Pine Mountain, 2010

Circle dance of students and staff on playground at Pine Mountain Settlement School, 1920’s. pmss001_bas098

Children dancing on the playground at Pine Mountain Settlement School, 1990s.

How do we manage our resources? How do we treat our neighbors? How do we educate our children to respect nature? What lessons are there in working with our hands as well as our minds and hearts? What is literacy? Reading? Math? Computer skills? Visual literacy? Civic responsibility? How can we eat healthy? How can we grow responsible crops? How can we exercise, intelligently? How important are aesthetics to our well-being? How can we help to shape our life-style into quality of life? How can we better respect our natural environment? Speak out when our water resources are in peril? Stop the removal of our mountains? What does it mean to have quality of life? These are short questions with life long answers. To seek answers to these questions and more, is the discovery of “educating for life” found at Pine Mountain School and in the surrounding community. In many ways it is the coming to a place and the discovering of it again, and again.

GO TO: DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH – IV – FARMING THE LAND

BACK: DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH I – ABOUT

![Boy's House Wassailers and Lords and Ladies -- 1946. [Good King Wenselaus ?] [In Laurel House] nace_1_025b.jpg](https://pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/nace_1_025b-1024x573.jpg)

![Angela Melville Album II - Part III. "E.K.W." [with dulcimer]. [melv_II_album_313.jpg]](https://pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/melv_II_album_313-194x300.jpg)

The isolation of the region was slowly but dramatically altered by roads, particularly

The isolation of the region was slowly but dramatically altered by roads, particularly