Pine Mountain Settlement School

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH

POST

1936 Pine Mountain Settlement School and Mexico

1936_mexico_009

ADVENTURE

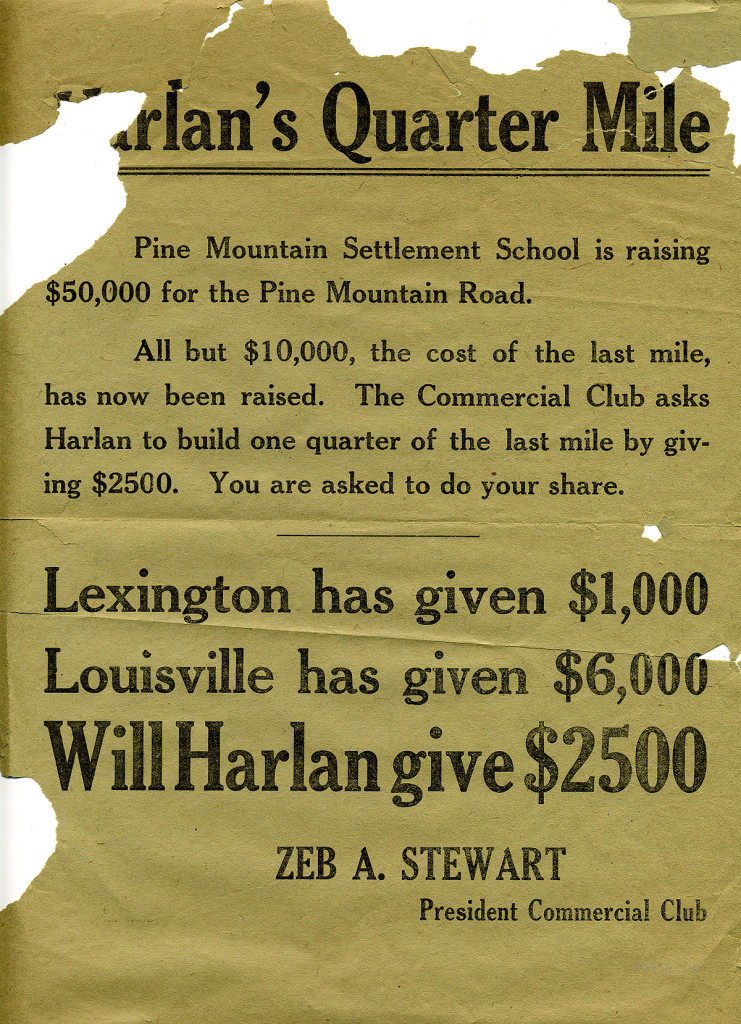

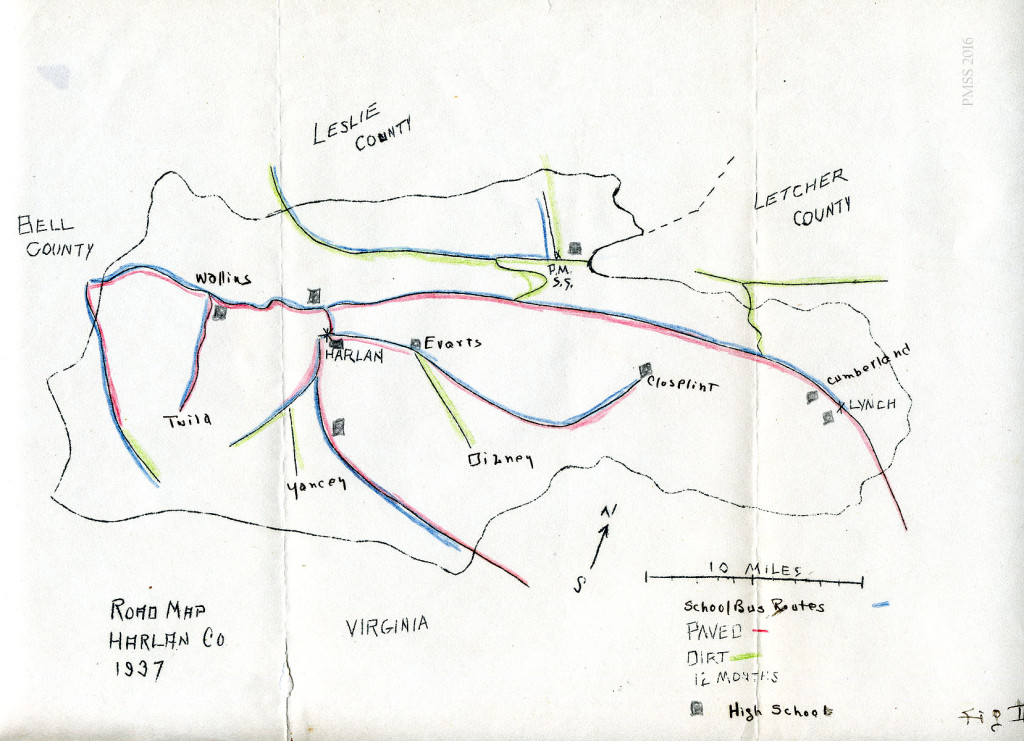

In 1936, the country of Mexico was opening up to travelers and cars. Some travelers were now able to make long journeys in the country and find the needed road assistance along the way. The Pan American Highway was still under consideration after it was first introduced at the Fifth International Conference of American States in 1923 but agreements to begin construction were underway and in July of 1937 when the participating countries signed the Convention on the Pan American Highway, construction began in earnest. The roads in the rural countryside, like those at Pine Mountain, were rustic and treacherous, at best. But it is unlikely that roads presented an obstacle to an adventuresome group from Appalachia.

Intrepid souls were venturing farther than just across the border and they navigated the roads of Mexico and beyond just as they navigated many of the rough roads that marked a large section of the rural United States. In the mid-1930s some of those intrepid travelers to Mexico were from Pine Mountain Settlement School. Following the closure of the 1936 school year, the Principal of the School, the secretary to the Director, and a rising star who had just graduated from the Pine Mountain Settlement boarding high school were given the opportunity to explore the world outside the United States. Accompanied by a proper school marm/administrator from Perry County, the quartet struck out for Mexico City and surrounding towns. Arthur Dodd apparently supplied the car and the camera, Fern Hall took notes, and Georgia Dodd supplied the vibrant dialogue, while all were observed by the quiet and reserved school administrator and first cousin of Fern Hall, Grazia Combs. In one touring car the group drove first to New Orleans where they explored the gulf port and the energetic life of one of America’s oldest cities.

1936_mexico_035 New Orleans

Leaving New Orleans, the group then headed for Texas where they planned to cross the border at Brownsville which sits just north of the large Mexican border town of Matamoros, Mexico. All we know is that they crossed the border into Mexico. Apparently, Arthur Dodd hoped to repeat the trip he had made in 1934, just two summers previous. What happened at the border is not certain. It is possible that the group took a train to Mexico City and rented a car within the country, or they may have driven the distance. That part of the story remains to be discovered.

The Mexican Highway 101, or the Carretera Federal 101, starting at Brownsville to Matamoros, is today a spur of the Pan American Highway that leads to one of the most treacherous highways in Mexico. But in 1935, it was an adventure, not a life-threatening drive, but also not for the faint of heart. To get some sense of highways in Mexico at this time, the home movie shot by adventurers in 1935, “Touring Mexico by Car, 1935“ should give some indication of the experience of driving to Mexico City during the early 1930s.

By 1936, Mexico’s Revolution had ended, Cardenas was installed as the new President of the country and oil was providing the country a new economy. Diego Rivera, Frieda Kahlo, Jose Clemente Orozco, and Siqueiros were making their new revolutionary voices heard in the murals and paintings shared with the Mexican people as well as with a new and eager North American tourist clientele. North American artists and the adventurous were frequently traveling to Mexico. For example, Anni and Josef Albers who were in residence at Black Mountain College in North Carolina in 1935, drove the 2000 miles to Mexico City where they both fell in love with the culture and lively art of the country. They returned many times from 1935 to 1967 and brought back elements of the culture that were literally woven into their art. As a weaver, Anni Albers was particularly sensitive to pattern and textures. Motifs taken from native Mexican weaving and ceramics show up in many of the Albers work and the vivid and subtle color of native arts and natural landscape were evocative inspirations for the Albers color theory.

EDUCATIONAL EXPERIMENTATION

Pine Mountain Settlement School had much in common with Black Mountain College in North Carolina and the exchanges between the two directors of the institutions occurred regularly. Glyn Morris, a Welchman by birth, became the Pine Mountain director in 1932. He had been deeply schooled in the Progressive educational models of John Dewey and nurtured by the reformed theology of Reinhold Niebuhr. John Rice, the Black Mountain College director, was a follower of Dewey and later a friend of the progressive educational reformer. Both Morris and Rice ran institutions that favored an educational model that was less a traditional educational institution and more a controlled educational experiment to test their theories.

John Andrew Rice, just fired from Rollins College in Florida because he wished to abolish grading and other progressive ideas, was in a hurry in 1933. He wanted to try out his ideas. When he came to Black Mountian he rushed the framework of a new institution into reality through what one observer noted was like a “pick-up game of football.” Further, Black Mountain College was born during the Great Depression and the pragmatism of Dewey and his views on art were easily integrated into the curriculum.

Glyn Morris, just out of Union Theological Seminary in New York City was also in a hurry the year earlier, to make his own mark on the world in another corner of Appalachia. When Glyn Morris landed in Pine Mountain Settlement School in 1932, the country was in the beginning stages of the Great Depression. It is not remarkable that the two directors found one another.

One major stumbling block, however, in a love affair between Black Mountain College and Pine Mountain Settlement School, was Rice’s disaffection for Robert Maynard Hutchins. Hutchins aimed to promote a kind of general education that would be comprised of fundamental ideas but would aim to end in intelligent action guided by practical wisdom. Rice did not envision his educational model following Hutchins’ fundamentalism and by 1937 he felt secure enough in his own model to attack Hutchins “General Education” plan in an article in Harpers, “Fundamentalism and Higher Learning,”

Robert Maynard Hutchins was the brother of Francis Hutchins, who became President of Berea College in 1939, and a major force in shaping the later years of Pine Mountain as a member of the Board of Trustees. Francis Hutchins had been in China in the mid-1930s as the director of the Yale in China program and followed his father, William Hutchins, as President of Berea College and. Francis Hutchins, as Berea’s President became a key supporter of Morris at the end of his tenure at Pine Mountian.

The relationship of the Hutchins with Pine Mountain did not appear to dampen the friendship of Rice and Morris and both adopted a “no-grades” approach to their educational programs. But, when Robert Maynard Hutchins, then President of the University of Chicago published his book, The Higher Learning in America, (1937) which outlined what he sought to do at Chicago with regard to reforming the curriculum. Robert Maynard Hutchins’ reforms infuriated John Rice at Black Mountain and confounded Glyn Morris at Pine Mountian.

At Pine Mountain, Glyn Morris walked a delicate line between the John Rice’s preferred experiential model of education, one not so fundamentally grounded in text and the more sequential and proscribed program of Hutchins at Chicago. In his 1937 article for Harper’s magazine, “Fundamentalism and the Higher Learning,” Rice blasted Hutchins’ model as “removed from experience.” “Why,” Rice asked, “include what can be printed and leave out what must be seen or heard?” [Reynolds, K. Visions and Vanities, p.147.] Rice elaborated

“Why include what can be printed and leave out what must be seen or heard: To some, Aeschylus and the sculpture of Chichen-Itza are in quality very near together. But we are to exclude one because it cannot be got from a book?”

“…Education, instead of being the acquisition of a common stock of fundamental ideas, may well be a learning of a common way of doing things, a way of approach, a method of dealing with ideas or anything else. What you do with what you know is the important thing. To know is not enough.”

While this discussion of Rice and Morris may seem outside the scope of the Pine Mountain connection with Mexico, there is a thread. This is found in the dual role educational experimentation had on Pine Mountain and Black Mountain and which paved the way for the groups’ travels to Mexico. What could be more experimental than such a far-flung journey of educators and students. It was the equivalent of today’s educational “travel abroad”.

Glyn Morris, the Director, and Arthur Dodd, the Pine Mountain School Principal, and leader of the Mexico trip, had frequently entertained Black Mountain faculty and students at Pine Mountain and the two had also visited in North Carolina meeting and speaking with many of the faculty there and at the nearby Asheville Farm School.

In the coal fields of eastern Kentucky, unionization was also heating up and the so-called “Coal Wars” were underway. Charges of Marxism and Communism were creeping into the language of the area and Europe was undergoing major political shifts. Trotsky was still in Norway but would sail for Mexico within the year and arrive in Mexico in 1937 where he would share a residence with Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo in the famous Casa Azul or Blue House in the Coyoacan area of Mexico City. “Mexico,” as the largest Mexican city is called, was in 1936 a sprawling and cosmopolitan city that was generating enormous creative, political, and social energy that flowed North to a young and welcoming and eager intellectual population. It was the poor traveler’s European or International Immersion.

1936 GLYN MORRIS AND EXPERIENTIAL EDUCATION

In his autobiography, Less Travelled Roads, (1977) Glyn Morris, the Pine Mountain Director, makes a case for experiential education and cites the growing trend across the country which found that educated rural youth were not returning to their rural home areas but were joining the growing numbers in suburbia and now, urban centers, and ultimately to countries abroad. Morris’s educational plan was progressive but it was also pragmatic. What Morris and Dodd and all the early Progressive pioneers at Pine Mountain would not live long enough to see was the migration back to rural home areas by the youth who years earlier had departed. There was a gradual retrenchment in the heightened exploration and curiosity of the youth about the world as they measured what they had against what they thought they desired. For men, the ultimate going away and coming back was War. But, that came later.

Morris, for example, declares

Regardless of the school’s program, its net result was to whet the students’ appetites for a quality of living simply not possible in an isolated, sparsely settled mountain community. It is a well-established historical fact — and is a fateful and challenging human problem, very obvious today. Even a relatively prosperous and self-contained family farm of twenty-five years ago can’t make it today on good soil, let alone in the Appalachian Mountain. In addition to this fact, a number of our students came from coal camps in the surrounding counties, and to expect the student to route himself into a career as a coal miner was unrealistic. I began, early in my term at Pine Mountain, to question the goals not only of Pine Mountain but of all the many private secondary schools and colleges in the mountains which asserted this unrealistic goal. My viewpoint on this matter was expressed to Dr. Harold Spears, formerly Superintendent of Schools, San Francisco, California, now Professor of Education at San Francisco State College, during his visit to Pine Mountain late 30s.

THE JOURNEY AND THE TRAVELERS

This long detour into educational philosophy has a relationship to the Mexico trip. As an experimental settlement school, Pine Mountain was continually looking for innovative ways to open up the educational experience for both its teachers and its students. When Arthur Dodd headed to Mexico for the second time with a car full of single women, he was probably thinking about the very good odds for himself, but he was also doing just what Pine Mountian did best. He was providing an optimum opportunity to expose the students to a new world and to give his very proper School Principal from Perry County an opportunity to open up her own educational perspectives.

Georgia Ayers, the Pine Mountain student who had just graduated and who was among the Mexico travelers, was one of five girls selected from the graduating class of 1935 to remain at Pine Mountain and to participate in a rural education program. Dodd and Morris had devised and proposed a program in which the high school girls would visit homes in the community to nurse sick children or mothers, carry library books to homes, and assist in instruction in the area’s one-room schools. A catalog of responsibilities was constructed that acted as a guide for each girl’s participation in the program. Morris’s and Dodd’s new program became the core of the 11th-grade experience in a new curriculum. Georgia Ayers became the first supervisor of this experimental program as it was built into the new progressive curriculum. The Mexico trip was, in essence, her training and her interview.

1936_mexico_047. Grazia Combs, Georgia Ayers, Fern Hall.

THE ITINERARY

Arthur Dodd‘s earlier itinerary (if it can be called that) to Mexico in 1934 in the company of Caleb Shera, son of a former art teacher at Pine Mountain, and August Angel was very loose. The trio had planned to travel by car to Mexico City but when they reached the border they found that the road was impassable in some sections. August Angel, in assembling his memoirs recalls the journey of the trio

In the summer of 1934, Caleb, Mr. Dodd, Principal of Pine Mountain Settlement School from which Caleb graduated from high school, and I, drove to Mexico in a Ford touring car for a summer vacation. We took turns at the wheel as we traveled. In Georgia, we stopped at Mr. Dodd’s home and stayed overnight. After a sumptuous evening meal and memorable homemade ice cream topped with fresh sliced peaches for breakfast, we drove south to Laredo, Texas, to cross the border into Mexico and toward Monterey.

We drove as far south as Tamazunchale, where we learned that the mountain road to Mexican DF [Mexico City] was under construction and we could not traverse. We decided to take the passenger train from Vera Cruz to San Luis Potosi, then transfer to a second, ending in Mexico City. We traveled second class, sat on slatted wood benches, and mingled with natives who were aboard with livestock, pigs, kids, fruit and vegetables to sell to passengers, or going from the countryside to nearby market places in towns along the railroad tracks. It was a day and night trip, and also a social encounter that shocked us to remember to this day.

In the city itself we did the usual sights – bullfights, opera, church, parks and museum tours, and a visit to the pyramids of the Sun and Moon. Mr. Dodd ate or drank something and caught the bug we dubbed “Montezuma’s Crud,” and spent a miserable month starving himself to get rid of it.

…. The six weeks we were on the trip cost me only $60. I started with $75 and returned to Kentucky with $15. Those were the good old days! It was a truly good vacation and affordable.

Though Dodd had a bad bout of dysentery it did not seem to dull his appetite for Mexico and this time he brought along a good body of film stock and camera.

In the 1930’s many tourists were traveling to Mexico and “the tour” was variously described by those who made the journey. One comprehensive travel account that has an interesting connection with Pine Mountain was recorded in 1936 by J.C. Nichols of Kansas City. Nichols was a friend of the Hook family of Kansas City and reportedly sold a lot he owned in the Rockhill Park area of Kansas City to Bertrand Hook who passed it along to his daughter. Mary Rockwell Hook, the daughter, was the architect for most of the buildings at Pine Mountain Settlement School. Because Mary was a fledgling architect in 1908 her father sought to further her career by purchasing the lot from Nichols so Mary could design and build her first house. To get a sense of a typical itinerary in Mexico see J.C. Nichols account “Our Trip to Mexico August and September 1936.”

The travels of the 1936 Pine Mountain Settlement School group took them to three major destinations: Mexico City, Puebla, and Taxco. Included in Dodd’s photographs are road shots of the countryside as the group drove along the roads connecting Mexico’s urban centers. In Mexico City, the photographs mainly concentrate on Chapultepec Park or “Bosque de Chapultepec” (Chapultepec Forest). It is the largest city park in the Western Hemisphere and covers just over 686 hectares or 1,695 acres.

![1936_mexico_040. "Charros - Mexico City Park." [Chapultepec Park]](https://pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/1936_mexico_040-644x1024.jpg)

1936_mexico_040. “Charros – Mexico City Park.” [Chapultepec Park]

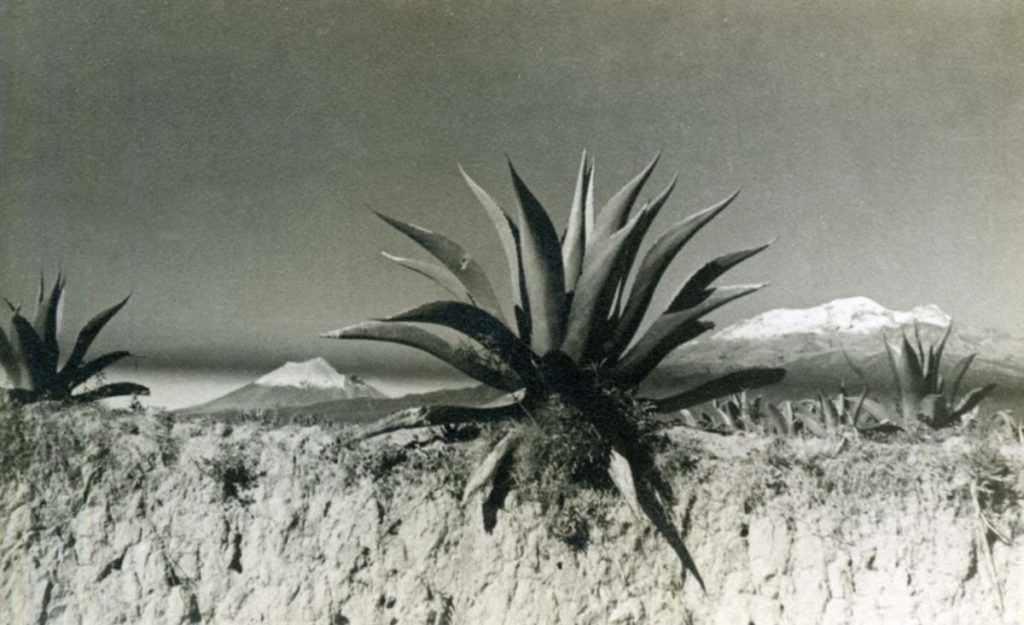

1936_mexico_005. View of Popocataptle and Iztaccihuatl volcanos. 70 Km Southeast of Mexico City.

A highlight of the trip to Mexico City, if measured by the number of photographs, was a trip to the ancient bullring Toreo de la Condesa in the Condesa neighborhood of Mexico City. Today the older bullring has been replaced by a new stadium in another location and the capacity doubled. The older location was overwhelmed by the rapid development of the Condesa area of the city. Apparently, the group saw a mind-numbing number of bull fights. Fern Hall wrote in a postcard to her future husband, William Hayes, the farm manager at Pine Mountain, that she saw six bulls killed that day. We don’t know what he thought about that report but it is likely that he was not cheering for the matador.

1936_mexico_045. Postcard. “Pase Natural, 319”

So, outcomes? Arthur Dodd managed to stay healthy and to enjoy the second trip to Mexico and return to Pine Mountain where he administered the school programs until their closure in 1949. Georgia Ayers returned to Pine Mountain where she eventually married Arthur Dodd. On her return to the School, she was not only “interviewed” to head the new social services program at Pine Mountain, she had evidently also “sized up” by Dodd, the adventuresome single man. He asked Georgia to marry him and they became a Pine Mountain couple. She married in late December of 1940. After her marriage, Georgia became the dietitian for the School. Georgia’s trip was the first of many journeys that Georgia and “Dodd” would take later in their lives.

Fern Hall continued on as Secretary to the Director at Pine Mountain and in 1941 married Wiliam Hayes, a former student who had stayed on at Pine Mountain as the Farm Manager and instructor in the industrial training program. The Hayes’ stayed on until 1953 when most farming programs at the School were discontinued. It is Fern’s set of Dodd’s Mexico photographs that prompted this blog. Fern and Bill’s daughter, Helen, inherited the photographs and with them a curiosity for travel first in Mexico in 1963 and then in other regions of the world. Grazia Combs returned to Perry County where she continued to teach and assume multiple roles in education in the county including Principal of Dilce-Combs High School and later Perry County Superintendent of Schools.

GALLERY: 1936 PMSS & MEXICO

- 1936_mexico_001. “Mexico City Market.”

- 1936_mexico_002. “Mexico City Market.”

- 1936_mexico_003. “Chapultepec Park.” Mexico City

- 1936_mexico_004. Diego Rivera’s Residence.” Mexico City

- 1936_mexico_005. View of Popocataptle and Iztaccihuatl volcanos. 70 Km Southeast of Mexico City.

- 1936_mexico_006. View of Popocataptle and Iztaccihuatl volcanos. 70 Km Southeast of Mexico City.

- 1936_mexico_007. Inn

- 1936_mexico_008. “Mexican Market”

- 1936_mexico_009. “Jungle on road to Mexico City.”

- 1936_mexico_010.”Jose”

- 1936_mexico_011. Man, burro and load of corn.

- 1936_mexico_012. [Chapultepec] “Park, Mexico City.”

- 1936_mexico_013. “Bell-ringer – Puebla.”

- 1936_mexico_014. “Mexico City” Bull Fight.

- 1936_mexico_015. Mexico City Bull Fight.

- 1936_mexico_016. Mexico City Bull Fight.

- 1936_mexico_017. Mexico City Bull fight. Woman.

- 1936_mexico_018. “Mexico City” Bull Fight.

- 1936_mexico_019. Young boy.

- 1936_mexico_020. “Mountains, Mxico.”

- 1936_mexico_021. “Taxaco”

- 1936_mexico_022. “Taxco.” Fern Hall and Georgia Ayers.

- 1936_mexico_023.”Taxco”

- 1936_mexico_024. “Taxco – Gringo Artist.”

- 1936_mexico_025.”Taxco.”

- 1936_mexico_026. “Market – Taxco.”

- 1936_mexico_027. “Taxco Market.”

- 1936_mexico_028. “Taxco.”

- 1936_mexico_029.”Local Wishy-washy.” Taxco.

- 1936_mexico_030. “Taxco.”

- 1936_mexico_031. “Taxco”

- 1936_mexico_032. “Taxco”

- 1936_mexico_033. “Tamazunchale Tourist Court.”

- 1936_mexico_034. “Taxco.”

- 1936_mexico_035. “New Orleans”

- 1936_mexico_036. “Pueblo.”

- 1936_mexico_037. “Taxco.”

- 1936_mexico_038. Cactus.

- Grazia Combs and Fern Hall, 1936. [1936_mexico_039.jpg]

- 1936_mexico_040. “Charros – Mexico City Park.” [Chapultepec Park]

- 1936_mexico_041. Mexico City Bull Fight.

- 1936_mexico_042. “El Toro.” Mexico City Bull Fight.

- 1936_mexico_043. “Arena, Mexico City.” Bull Fight

- 1936_mexico_044. “Monterrey, Mexico.”

- 1936_mexico_045. Postcard. “Pase Natural, 319”

- 1936_mexico_046. Fern Hall and Georgia Dodd.

- 1936_mexico_047. Grazia Combs, Georgia Ayers, Fern Hall.

- 1936_mexico_048. Georgia Ayers.

Bibliography

Touring Mexico by Car in 1935 http://www.mexconnect.com/articles/4127-touring-mexico-by-car-in-1935

J.C. Nichols Mexico travel account “Our Trip to Mexico August and September 1936.”

Angel, August. Trivia and Me, 2008

![1938 [?], April 2. Note from Office secretary Fern Hall.](https://pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/spel_corrsp_043-150x150.jpg)