Pine Mountain Settlement School

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH

Moonshine and

“Hard and His Kettle” by

Henry Mixter Penniman

414 Two men standing and holding two bottles of what is surely moonshine(?).[creech_columbus_4_414.jpg]

TAGS: Dr. Henry Mixter Penniman, moonshine, distillers, Women’s Christian Temperance Union, W.C.T.U., Frances Beauchamp, Kentucky Federation of Women’s Clubs, Katherine Pettit, Ellen Churchill Semple, May Stone, Ethel de Long, Michael McGeer, Abner Boggs, Bish Boggs, Lucy Furman, Percy McKaye, John Fox Jr., William G. Frost, moonshine stills

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH Moonshine and Hard and His Kettle

MOONSHINE

Moonshine was not a favored drink of Kentucky Settlement School workers, but it was certainly a favorite topic of conversation and generated many a tall tale within and without the School and the surrounding community. The stories about moonshiners, moonshine stills, brushes with revenuers, and competition between distillers were often collected and repeated by workers, the community, and visitors to eastern Kentucky and other locations in the Central and Southern Appalachians. These tales abound in staff letters, diaries, and scrapbooks in the Pine Mountain Settlement School archive as vivid testimony to the production of corn liquor in the Kentucky hills.

When Katherine Pettit founded Hindman Settlement School with May Stone in 1902, near the small town of Hyden in Knott County, Kentucky, she was under the blessings of the W.C.T.U, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union and was quietly following the national trend toward Progressivism and Temperance. While the two may seem to cancel one another out, they were co-dependent partners in the opening years of the twentieth century, particularly in Eastern Kentucky.

THE W.C.T.U.

By 1910 and in the following years the term progressive was commonly used in a variety of political ways. [*See: Michael McGeer. A Fierce Discontent: The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 2003]. Hindman, in 1902, was in the mainstream of the progressive Settlement Movement but it was also under the influence of the other national trend, that is the WCTU or the Women’s Christian Temperance Union.

The WCTU provided funds for Hindman during its first thirteen years but the relationship soon began to unravel as the progressive ideas of Jane Addams and many of her colleagues saturated in progressive idealism did not play well with the WCTU. At the risk of the loss of funding from the WCTU, the women in Eastern Kentucky’s settlements held steady for the early institutional years as the WCTU funding comprised a considerable amount of the school’s operational budget.

During these WCTU early years, Pettit and Stone were bolstered by the Kentucky Federation of Women’s Clubs and a close friendship with Frances Beauchamp, the Kentucky president of the WCTU. With this strong but disparate support, Pettit and Stone mounted a vigorous campaign to eradicate alcoholism through a program of education that focused on social and moral reform and scientific agriculture. But, Pettit and Stone and their Women’s Club friends were not hatchet carriers like Carrie Nation. They believed that reform started from within and not from without. The emphasis placed on health work that Pettit learned at Hindman carried over into her work and programs at Pine Mountain.

Following the departure of Katherine Pettit to Pine Mountain in 1913, the funding from the W.C.T.U at Hindman dwindled, and the school experienced several disastrous fires that added to its woes. In 1915, two years after Pettit departed, Hindman experienced a “Broadening Out,” as they described it, and the name of the institution was formally changed from the W.C.T.U. Settlement of the Hindman Settlement School. The name change came just as prohibition began to be a hot political debate in the state of Kentucky and as the Progressive movement rose in favoritism. Frances Beauchamp, President of the Kentucky WCTU and a friend of Pettit, was soon the object of considerable “mudslinging” as described by Jess Stoddart in her well-researched history The Story of Hindman Settlement School (Stoddart 2002, p.82.)

While references to the W.C.T.U. school disappeared in the wake of the political battles of Prohibition, the settlement at Hindman was also charting a new and progressive educational course. Angered by the perceived retrenchment from prohibition, some significant donors pulled their support for the school. All the while, moonshine did not go away. It continued to light the midnight production of corn liquor, and the revenue continued to support families who lived on the economic margins of society. Moonshine, after all, was a very persuasive form of social capital not unlike that seen in many parts of the world, not just Appalachia.

Like Hindman, the relationship of Pine Mountain to corn liquor is a story that is not easily altered by a simple change of name. Nor is the Kentucky tale a unique one. “Localism” has sometimes been used to describe rural attachment. One of the most striking markers of Appalachia’s current return to what is often referred to as “localism” can also be found in locations as diverse as some South American countries and some countries in Asia, particularly in Thailand, Myanmar, and Vietnam. In those latter Asian countries, the nostalgia for social capital has been used to push for reform in health services, agriculture, and a variety of other older practices that were remembered as part of a healthy democracy.

It is interesting that place-based education, a kind of localism, has often returned to Indigenous knowledge and past practice for educational assistance to re-form and inform social capital. A brief visit of a group of Vietnamese visitors to Pine Mountain in the early 1970s revealed much about the common issues in the two countries, including the power of Asian “moonshine” cooperation to work its magic in restoring civic engagement and to nudge the people toward less destructive economic initiatives.

In Appalachia, drinking was a discreet part of many social gatherings. It enhanced conversation, made young men bold, softened the sensibilities of young women, and lessened the aching back of the subsistence farmer. In many cases, it was the juice of existence, providing desperate families a means of providing for a house full of children or a poor crop. But it is the stories of rampant drinking and associated violence like that documented in the records of the Hyden school and also at Pine Mountain, particularly in the health centers at Big Laurel and Line Fork, that are seared into the public mind.

The novels of Lucy Furman, a staff member at Hindman, and many other writers promoted “moonshine stories” to an eager national audience. Percy MacKaye, the playwright, John Fox, Jr., and other visitors to Pine Mountain continued to romanticize the practice of distillation of the mountain’s principal crop — corn. John Fox, Jr. was notoriously energized by the marketing of what Darlene Wilson, in her article for Back Talk From Appalachia (1999), called the “dichotomous stereotype of twin Kentuckys — the twins being the ‘…sneaky, murderous, moonshiners,’ versus the ‘civilized ‘outer-world’ of the rest of the state. (See: Wilson, Back Talk … p. 112). Yet, marketing and publications at Hindman and later at Pine Mountain can be found using moonshine stories to capture the imagination of an audience that believed the area to be rampant with stills and guns.

Unfortunately, the written records of the rural settlement schools, largely the record of “outsider authors”, gave credence to some of the tales of violence, redemption, and survival centered on moonshine. After all, in the 1920s, Harlan County’s murder rate was the highest in the country — a ready testimony to the mixture of guns and alcohol. “Bloody Harlan” was at its core a name born out of the mine wars, but the rage was often fed by corn liquor. But, then, even this story is much more complex than the easy tales often spun about moonshine in the mountains of Kentucky, and there is little doubt that it enables the easy path to the long road of stereotyping.

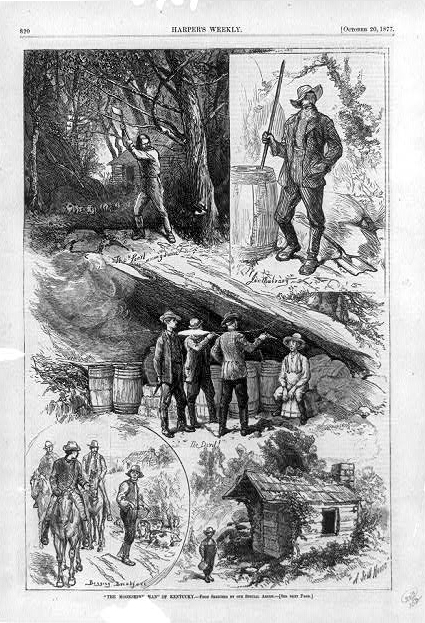

THE MOONSHINE MEN OF KENTUCKY

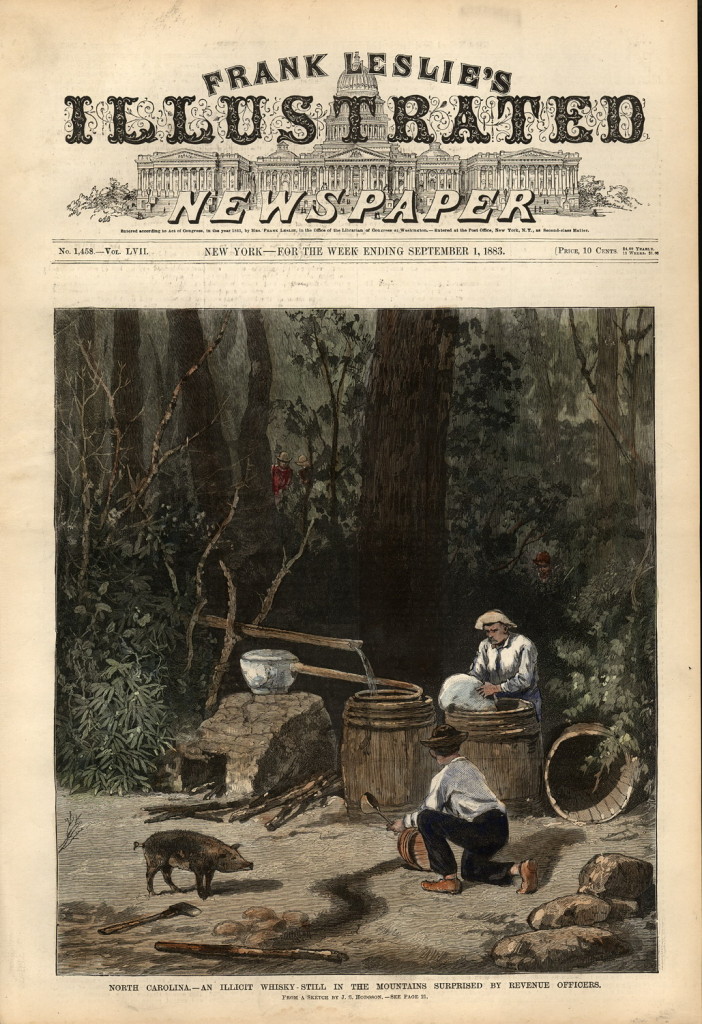

“The Moonshine Men of Kentucky,” Harper’s Weekly, October 20, 1877.[The_Moonshine_Man_of_Kentucky_Harpers_Weekly_1877]

The Pine Mountain staff and community also added to the many moonshine tales found in the public literature. After all, moonshine tales are good entertainment — tried and true fodder for many Appalachian tall tales. One of Pettit’s first traveling companions into eastern Kentucky was the “expert” on mountain moonshine tales, Henry Mixter Penniman.

DR. HENRY MIXTER PENNIMAN

The Rev. Penniman was a faculty member at Berea College in Kentucky and a self-described and well-known authority on mountain culture. It was Penniman who led Pettit and a group of fellow troupers into the eastern mountains to explore the Appalachian culture. This trip occurred before the Settlement School in Harlan County became Pettit’s passion. Berea often encouraged visitors and its own faculty to visit the rugged mountains of eastern Kentucky and to see first-hand how the “notorious” mountaineers lived. Often, visitor tours were directed and encouraged by the college President with the intent to seek out Mountain areas in need of educational support. The personal tour gave the travelers a deeper dive into the local culture of Appalachia.

Berea, for many years, provided consultation and support to the schools in the southeastern corner of the state and was particularly fond of Hindman and Pine Mountain. Many articles by William G. Frost, an early President of Berea, and by his faculty from the college, signaled that they felt the region to be under their informed care and their watchful eye. They kept in close touch with the settlement schools in the southeastern region, and “moonshine” was often part of their concern and sometimes and somewhat, their exaggerated focus and conversations. At Berea, Penniman was their moonshine expert.

Dr. Penniman, as a Berea College faculty member, was particularly concerned by lifestyles that he saw in the Southern Appalachians and the toll taken on the lives of mountain people. As someone who had built up good relations with many of the people in the southeast corner of the state, he became a close observer of the culture and of the language and the wry humor of the people of the region. Not much was missed by Penniman, as seen in two tales both collected and somewhat concocted and, reportedly, recited by Penniman in public performances. These selections from the Berea Quarterly have surrogate copies in the archival records at Pine Mountain Settlement and at Berea College.

THE BEREA QUARTERLY 1908, p. 20-22

Henry Mixter Penniman

QUARTERLY EDITORIAL NOTE:

Professor Penniman was born in Massachusetts, educated at Brown University and Andover Seminary, and has been connected with Berea since 1895. More than any other member of our Faculty he has assisted the President in making friends for our enterprise, and more than any other, except Professor Dinsmore, he has come into immediate contact with the mountaineers. He is what the Kentuckians call a “good mixer,” and he has preached on half the creeks in Eastern Kentucky, entering into the real life of the people with a sympathy which opens their hearts.

Professor Penniman has a keen sense of the ludicrous and a good scent for literary material as well. Instead of giving a statistical or scientific account, he gives pictures, impressions, which have made his presentations of the mountain work most attractive, in spite of his being a ”minister of the Gospel” he has become a great impersonator, so that a business men’s club. or a camping party in the Adirondacks counts itself fortunate when it can secure an hour of his recitals.

We find room this month for one brief anecdote which is almost a photograph, but a photograph selected with an artist’s eye. Following it is a testimonial which recently came to President Frost regarding Professor Penniman’s impersonations before well-known people in Cincinnati.

“DRUNK INNERCENT”

Henry Mixter Penniman

Splash, splash down the mountain passway, for the path lay in a stream fretting and playing in the narrows of a “V” shaped valley. A mountaineer on his big mule and a preacher on his horse, after a long, hot, hard day were riding forward in the edge of the night. The preacher was tired enough to fall off.

A long silence was broken by the man on the mule.

“Mr. Preacher, you’ve ben yere nigh six year an all thet time I’ve knowed you’ve wanted to ast me one thing an you ain’t ast hit. Now I’m goin to promise hit to ye without your astin.

“You’ve alius wanted to ast me not to drink no mo’. Now I promise I’ll drink no mo’.”

This was like a clap of thunder out of a clear sky. The horse moved over to the mule, and the big mountain hand almost crushed the preacher’s. The stump and rock in mid-stream that made them unclasp was a relief.

Again the silence was broken.

“Mr. Preacher this country will take notice that I am quitting and they’ll know you are into hit, and thars plenty of folks round yere will try and spile your mind about me. Now if you hear I git drunk come to me, ef I get drunk I’ll tell ye an I’ll still be a pullin’ to be a temperance man.”

Not long after, the preacher heard his mountain friend was drunk and riding to his cabin asked point blank,

“Did you get drunk?”

“Yes” was the answer,

“I got powerful drunk but I got drunk innercent.

” How was that?

“I’m troubled with cramps, when them cramps ketch holt I hev to hev some whiskey to subjew their pain and when I git nuf whiskey down to subjew their pain, hit onhinges my ides as to what’s right and I slip into the rest innercent.”

‘ ‘Mr. Preacher I don’t low hits wrong to take er dram, but I do say hits wrong to git drunk. I cayn’t tak er dram and not tak mo’, so I ain’t goin to tak er dram.” [Penniman]

In another of Penniman’s tales he tackles Moonshine head-on. This rambling story tells us of the adventures of “HARD AND HIS KETTLE”

“Hard and His Kettle” is a tale, among many, found in Penniman’s book, Moonshine Life of the Mountains of Kentucky (1908), which charts the use and abuse of moonshine in the Southern Appalachians. Penniman describes the many misadventures of “Hard and His Kettle” and outlines the serious impact liquor was creating for many in the region.

Found in the Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections, ”Hard and His Kettle” is a tale to remember. It is uncertain whether Penniman reproduced any more tales from the Pine Mountain region that join both pain and pleasure in the same manner as this graphic story does. There is no further record of Penniman’s return to the region of the Pine Mountain Settlement School and the School does not retain other Penniman writings. The particular “chapter” from Moonshine Life of the Mountains of Kentucky, printed here, is found in a typewritten copy of the article in the Berea Quarterly, Vol. 12, No. 9, 1908, also in the PMSS Archive. It skillfully captures the regional dialect and humor often found in the community around Pine Mountain and gives insight into Mr. Penniman’s enchantment with the region and the stories by and about the unique people of early and remote Eastern Kentucky. It varies only slightly from the Berea Quarterly version and appears to be a transcript and was found among the papers of the Pine Mountain Settlement School Director, Katherine Pettit.

Pettit, who was a personal friend of Penniman, had traveled with the Berea scholar when he was the leader and the “historian” for a Berea group that traveled deep into Harlan County in 1899. It was one of the earliest journeys that Pettit made to the far Eastern corner of the state, and that led her to the founding of Pine Mountain Settlement School.

Among the well-known adventurers in the Penniman and Pettit early foray into Eastern Kentucky was the Chicago sociologist Ellen Churchill Semple, whose anthropological insights and published work on the people of Eastern Kentucky continues to be debated. Another member of the large party of adventurers was the religious leader and Soul Winner, Edward O. Guerrant. The fascinating group and Penniman’s fascination with liquor use and woven coverlets likely energized young Pettit’s active imagination regarding the talented and challenging lifestyle of the people of early Eastern Kentucky. Her close family association with the early settlement of the State of Kentucky, her family history as a Daughter of the American Revolution, her passion for education, and her love of weaving were all forces that contributed to her drive to return and create a School in the far corner of Kentucky. Pettit’s first efforts at education at Hindman Settlement School form a remarkable early endeavor, but Pine Mountain Settlement School was her life’s work. Penniman was likely an important influence that fed Pettit’s life-long enchantment with the region.

[See also Ellen Churchill Semple, who accompanied Pettit and the group into Kentucky. See also the details of the early Penniman-led group into Eastern Kentucky as recorded in HISTORIES PMSS 1899 A Novel Excursion by Maria McVay. Katherine Pettit’s Journey with a Berea College Group into Harlan County in 1899 as Recorded by Maria McVay. hhw 2021-09-13

GALLERY

- “Hard and His Kettle,” from Moonshine Life of the Mountains of Kentucky, by H.M. Penniman of Berea College, 1908. 01 [penn_moonsh_001.jpg]

- “Hard and His Kettle,” from Moonshine Life of the Mountains of Kentucky, by H.M. Penniman of Berea College, 1908. 02 [penn_moonsh_002.jpg]

- “Hard and His Kettle,” from Moonshine Life of the Mountains of Kentucky, by H.M. Penniman of Berea College, 1908. 03 [penn_moonsh_003.jpg]

- “Hard and His Kettle,” from Moonshine Life of the Mountains of Kentucky, by H.M. Penniman of Berea College, 1908. 04 [penn_moonsh_004.jpg]

- “Hard and His Kettle,” from Moonshine Life of the Mountains of Kentucky, by H.M. Penniman of Berea College, 1908. 05 [penn_moonsh_005.jpg]

- “Hard and His Kettle,” from Moonshine Life of the Mountains of Kentucky, by H.M. Penniman of Berea College, 1908. 06 [penn_moonsh_006.jpg]

The thirst for tall tales can be read in Hard’s hard tale but there were similar fascinations with mountain stills, like that illustrated in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper from 1883. Both accounts illustrate the distillation process of the famous mountain drink and embellish its furtive creation.