Lewis Lyttle ( ) – A Key Player in the Founding of PMSS

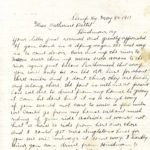

Lewis Lyttle (1868-1950).[rood_083.jpg]

Reverend Lewis Lyttle, an itinerant Baptist preacher, knew intimately what he was writing about in his 1911 letters to Katherine Pettit. During his visits to the Pine Mountain area as a mountain missionary attending to the spiritual needs of the community, he learned firsthand the severe educational, medical, and cultural needs of the people. When he wrote to Katherine Pettit in the first years of the 1900s his letters were impassioned pleas for the people of the region. He asked Pettit to consider building a new school on a portion of land that he had seen and that he suggested was rich with potential for a school. He wrote,

“I think there is a good place here where Greasy, Middle Fork, Line Fork, Straight Creek, Leatherwood, and Cutshin, all head in against the Pine Mountain. Pure air, pure water, and plenty of children to enjoy it.”

Lyttle, having seen Pettit’s work at WCTU (Women’s Christian Temperance Union) Settlement School (later known as Hindman Settlement School), had every hope that the same could be done in Harlan County in the Pine Mountain Valley. It was clear to Lyttle that Pettit had the skills that could handle such an endeavor. Pettit not only understood the needs of the area but she also had a reputation for action and a no-nonsense leadership style that had already proved effective in the founding of the Hindman Settlement.

Rev. Lyttle wrote to Pettit

“I would shrink from asking anyone but you to undertake to start a school in such conditions as we will have to meet but I know you understand them.”

Lyttle had ideas but no money, no land, and no aptitude for breaking ground, building out the facilities, or negotiating the finances. However, he knew landowners and community leaders who had these skills — and he knew Katherine Pettit — at least he believed he did.

Lyttle began by preaching the idea of a school to the community. As Lyttle’s idea of a new school began to take shape in the mind of the community, William Creech and other valley families such as the Metcalfs, the Turners, and others called for a school, Lyttle continued to serve as a liaison between the community, the landowners, and with Pettit and later with Ethel de Long, her co-worker at Hindman.

Katherine Pettit and Ethel de Long had been struggling with their roles at Hindman and were ready for a new venture. Negotiating the exit from Hindman was not easy but Pettit smoothed the edges. She was both a masterful negotiator and a fiercely independent presence. By suggesting the Pine Mountain idea as an extension of the settlement idea, she kept her relationships at Hindman while convincing Ethel de Long, one of Hindman’s most progressive educators to join her in the Pine Mountain venture. The Knox County school was struggling with increasing costs, a lack of farming land, and a dwindling donor base.

Pettit and de Long became the co-founders of the Pine Mountain Settlement School. Building on the ideas of William Creech and his generous donation of land. the two women ventured deeper into the Appalachian mountains. Their sanguine and determined success in founding the institution at Lyttle’s suggested location was a convergence of luck, savvy, and timing. The resulting institution was also a school with a well-chosen mission. It was one that has proved resilient enough to last for over 100 years. Part of the resiliency of Pine Mountain Settlement was the ecumenical foundation that Pettit and de Long instituted. It was a foundation that served the future. Successors in the governance and administration worked within the flexible framework established by the founders and ensured its longevity.

While Lyttle was strongly immersed in his Baptist roots, he was also a pragmatist. The School was never sectarian but was founded as a Christ-centered institution, not under the sway of any one religious denomination. Like Lytle and William Creech, the primary goals Pettit and Zande chose to address were education, civic responsibility, and human empathy.

In the letters of Lewis Lyttle to Katherine Pettit, one can feel the urgent appeals to reform all three important areas of life in the community. Education, civic responsibility, and human empathy do not take easy to reform. In the area surrounding the new school, the challenges were enormous. Feuding, drinking, and carousing had become a sport. Lyttle in a letter to Pettit asked that she build a school that would “invest in the character of these boys and girls.” The letters, recently added to the Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections website, present an early road map to the development of the School and education, civic responsibility. and human empathy in the area of service.

THE ECUMENICAL APPROACH

Pettit and many of her colleagues at Hindman were steeped in the national Settlement Movement that was centered on the work of Jane Addams at Hull House in Chicago. The urban movement had much in common with the strong egalitarian and independent attitudes of mountain people. Both the early settlers of the Southern Appalachians and the founders of the Settlement Movement shared many of the precepts of the prevailing Protestant religions of the day — Methodists, Presbyterians, Lutherans, Congregationalists, and Baptists. Later years brought many other religious practitioners to the area such as Shakers, Mormons, Catholics, Mennonites, Buddhists, Muslims, Jews, Shinto, and others. However, no religion was as entrenched as dramatically as the Baptist sects.

In the early years of the twentieth century, Lewis Lyttle, as a Baptist itinerate preacher, knew he would never be far from a call to preach in the Central Appalachians. In the 18th century, the Presbyterians held sway in many pockets of the region but the religion did not meld well with the isolation and independent dwellers of the mountains. Many, if not most were descendants of the early European Dissenters and dissimulation was a second nature. But, as the population demographic changed with the industrial age of coal, this heritage of dissimulation, found mainly in Baptists and their many splinter denominations, began to shift.

The shift within the greater population of the Central Appalachianssectarian institutions, but Pine Mountain funded on a non-sectarian base, did well. Early in the settlement of the Central Appalachians, Baptist sects dominated many rural communities. An inventory of denominations in 1900 shows Baptists accounting for more than one-third of the total church memberships in the mountains of Kentucky. With the Bible as their supreme guide, many splinter groups reserved their right to their interpretation of the Holy Word, and small churches were established in the many small communities. The families were often defined by their geography and their kinships, more than their adherence to a specific dogma.

This fragmented geography, population, and religious disparity of the so-called “Southern Mountaineers” led Samuel Tyndale Wilson in his book, The Southern Mountaineer (1906) to declare in his small book, that the “Appalachian Problem” was found in its seven peculiarities: deep-seated Americanism; Protestantism; White; Country [i.e. rural]; Varied and Complex; Delicate; and Urgent. Wilson was a student and then a professor at Maryville College in Tennessee,

Writing from a Presbyterian perspective, Wilson and others have been described as leaders in shifting the focus of social/religious uplift from the Black South to the Appalachian mountaineer. The “problem”, as seen by Wilson and many others of his time, was

“How are we to bring certain belated and submerged Appalachian blood brethren of ours out into the complete enjoyment of the twentieth-century civilization and Christianity?”

The difficulty with this “problem,” was the many varieties of “Christian” and the growing competition for souls. Further, some “soul winners” held more sway than others in Eastern Kentucky.

SOUL WINNERS AND THE REV. EDWARD O. GUERRANT

Kathrine Pettit was strongly influenced by the Social Gospel Movement and the work of The Reverend Edward O. Guerrant, who was a family friend, a physician as well as a minister. Guerrant, founder of the “Soul Winner Society,” spent many years in the mountains of eastern Kentucky. Along with the Rev. Stuart Robinson (1814-1881), he was instrumental in bringing together many of the ideas of the Settlement Movement into mountain mission work. Both Robinson [Stuart Robinson School, Blackey, KY] and Guerrant [Witherspoon College (Buckhorn School) and others] dominated the religious landscape of Eastern Kentucky. While a direct connection cannot be established between Guerrant and Lyttle, it is sure that they were familiars.

While Guerrant’s “Soul Winner” sounds like a competition for souls, the Social Gospel that Guerrant proposed was more one of conciliation, and his role was one of a conciliator between the various religious factions. Guerrant saw the Soul Winners as inter-denominational — not favoring one religion or sect over another. From his base near Mt. Sterling, Kentucky, and not far from Berea College, Guerrant could easily strike out to the mountains of Eastern Kentucky.

What is more well-known is the influence of Guerrant upon the Pettits in their Blue Grass household near Lexington where he was frequently a visitor. His many tales of the area had long been shared with his friends the Pettits. Guerrant’s ideas likely stuck with Katherine Pettit as she listened to the banter in her household as she grew up. Following her junkets into the eastern mountains she began to know all too well how fragmented the religious tenets were in the region. On the need to exercise caution and more than a little conciliatory wisdom, Lyttle, Pettit and Guerrant were all in accord.

Pettit entered the region remarkably well prepared for the task before her. Working with Lyttle and under the shadow of the work begun by Guerrant and other progressive reformers, Pettit was able to adapt the settlement movement initiatives. She had learned first-hand at Hindman the basics and she adapted those and melded them with the missionary energy found in the early Appalachian mission schools. The early residential schools that grew under the watchful eye of Guerrant became a lasting model for Pettit. However, the lessons learned in those decidedly sectarian models were modified by Pettit and de Long. Their vision grew into a push for a non-sectarian and strong educational combination — Christian, but not bound to any denomination or sect. Pettit moved forward with a studied Progressive force, a hands-on agricultural knowledge, and a deep commitment to the lessons learned in the Settlement Movement. Pettit was more intent on enriching minds, bodies, and character than on sending souls to heaven. She was, as described in the article by

RECORDING COMMUNITY

The letters of Lewis Lyttle and the insights pulled from the writings of Katherine Pettit reveal an informal, interpretative, and practical view of community development in the early years of the Pine Mountain Settlement School. The School’s relations with the Pine Mountain valley and its people focused on education and agrarian reform It is clear from the letters of Pettit and Lyttle that the nature of the community fascinated them. Not just the “kivers” that Pettit so diligently collected, but the language, the agricultural practice, the relationships, show Pettit’s deep love for the land and the people. She spent a lifetime gathering snippets of wisdom which she recorded in her “Common Book,” a scrapbook of common wisdom, quotes, ideas, Biblical interpretations, and medicinal and mental health practices. The “Common Book,” held by the University of Kentucky, with copies at Berea and a poor mimeograph copy at Pine Mountain, is probably the most intimate record we have of the corners of early Appalachian life that are so difficult escribe. That Pettit was fascinated these “snippets” is much more that just a curiousity. The cultural picture gleaned from the scrapbook informs both Pettit and her Pine Mountain community. As a record of Pine Mountain’s essence and that of its founder, the “snippits” are, perhaps, as close as we will get to an understanding of Pettit and hr motivations.

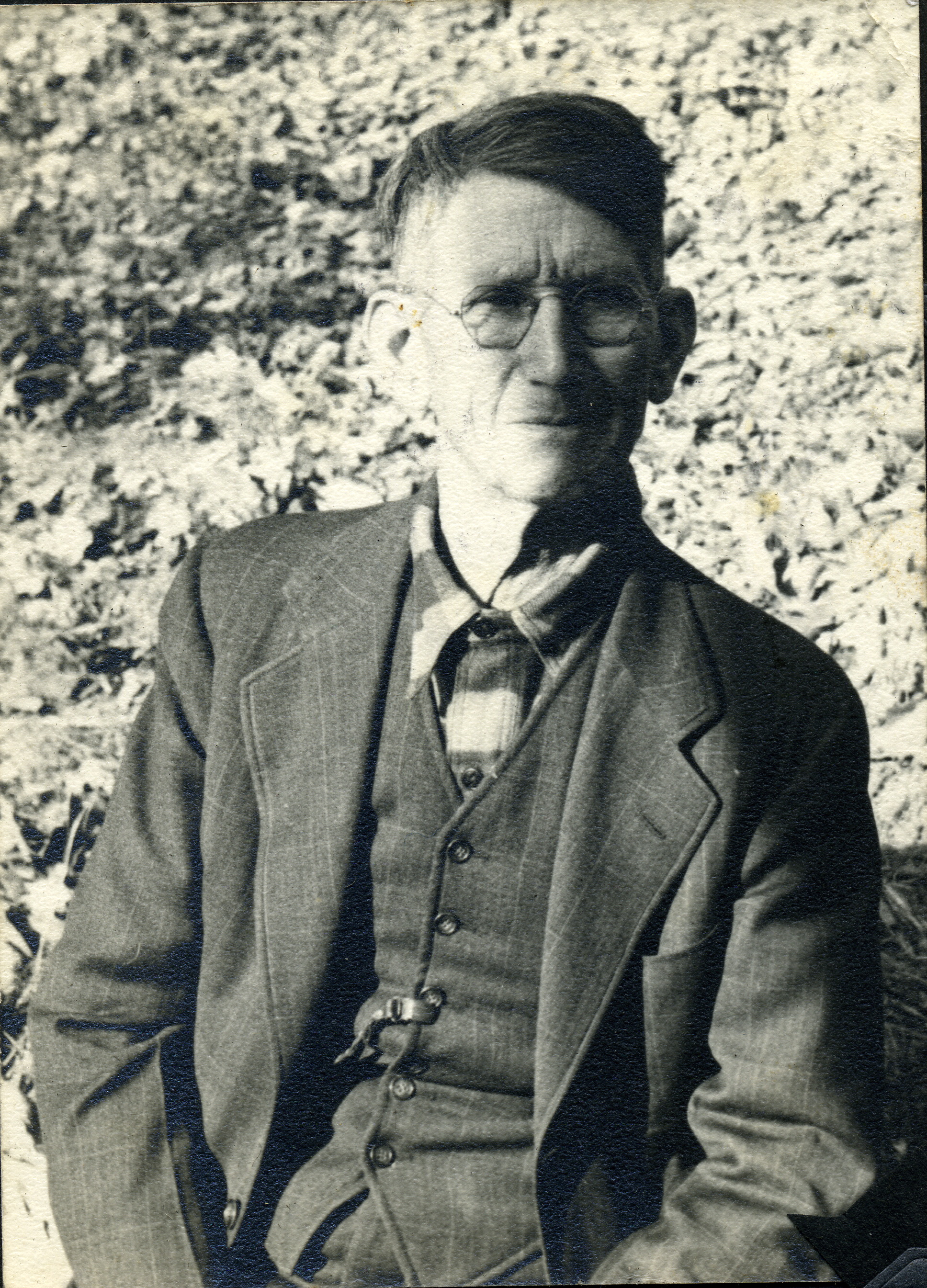

- Lewis Lyttle letter to Katherine Pettit May 9, 1911, p. 1. [lyttle_pettit_1911-05-09_001.jpg]

- Lewis Lyttle letter to Katherine Pettit May 9, 1911, p. 2. [lyttle_pettit_1911-05-09_002.jpg]

The letters of Pettit are anther means of getting close to the enigmatic founder, Katherine Pettit. They come close to revealing her motivations and her hidden personality. In the small body of personal comments found in her letters and tjose of her correspondents, Pettit’s personality begins to take shape.. It is unlikely that an intimate portrait can be drawn, but the letters help to give shape to her planning processes. Through time the history of Pine Mountain Settlement School is revealed in its letters — internal and external..

Both Lyttle and Pettit worked diligently to contribute to the institution even after retirement. Lyttle continued to preach and as a formidable Harlan County Judge, he raised “judgement ” to another level — that of civic judgement. Until her death in 1938, Pettit kept an ever-watchful eye on the School and in a scattered array of letters she kept a watchful eye on the institution to which she gave birth and longevity. She contiued to keep in touch with Lyttle, and it is difficult to tell if she was at his beck and call or if he was responding to the force of her powerful personality. The lessons and the synergy of both are woven into the fabric of the School.

HHW w/ light editing by AAE

See Also:

LEWIS LYTTLE Rev. Biography

KATHERINE PETTIT Biography

KATHERINE PETTIT CORRESPONDENCE 1911 August – December

In these letters by PMSS’s co-founder, the seeds of PMSS were planted and planning for a school began.

KATHERINE PETTIT CORRESPONDENCE 1911 My Dear Friend Letter, May 27, 1911

This letter, dated May 27, 1911 and written by Katherine Pettit, recounts a visit by Pettit, Rev. Lyttle, PMSS nurse Harriet Butler and Stephen Guilford (a former Hindman student) through four Eastern Kentucky counties to view a site at Pine Mountain that was proposed by Rev. Lyttle for a new school and for Pettit to visit homes that wove “coverlids” — Pettit’s strong interest.

An earlier trip to Pine Mountain by both Pettit and de Long was recorded by Lewis Lyttle to have taken place in the spring of 1910. That visit was described by Pettit when the vision she held for so long began to be realized to build an industrial training school in the mountains. Enthusiastic descriptions in Pettit’s earlier letter were used in de Long’s 1911 letter as a way to prompt readers to make donations.

This is a critical document for the Pine Mountain Settlement School as it shows the early passion of Pettit to build a school at Pine Mountain while she was still at Hindman and maps to the later Ethel de Long DEAR FRIEND Letter of 1911 which was a fundraising letter to start the institution at Pine Mountain.

DEAR FRIEND Letters 1911 (Hindman) (Signed by Ethel de Long.) This early fund-raising letter by Ethel de Long appears to rely on a previous Katherine Pettit letter which de Long says inspired the move to Pine Mountain by the two founders.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Horine, Kristy Robinson. “Practical Idealist,”

Wilson, Samuel Tyndale D.D., The Southern Mountaineers, New York: Literature Dept., Presbyterian Home Missions, 1906.

LEWIS LYTTLE Letters to Katherine Pettit 1911

LEWIS LYTTLE Letters to Pettit and Nolan 1912

LEWIS LYTTLE Rev. Biography