Pine Mountain Settlement School

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH

Earth Day and Mary Rogers

1970 – 2024

EARTH DAY

“Oh, no man knows through what wild centuries roves back the rose.” Suddenly time disappeared and I seemed to be looking down the vistas of eternity.”

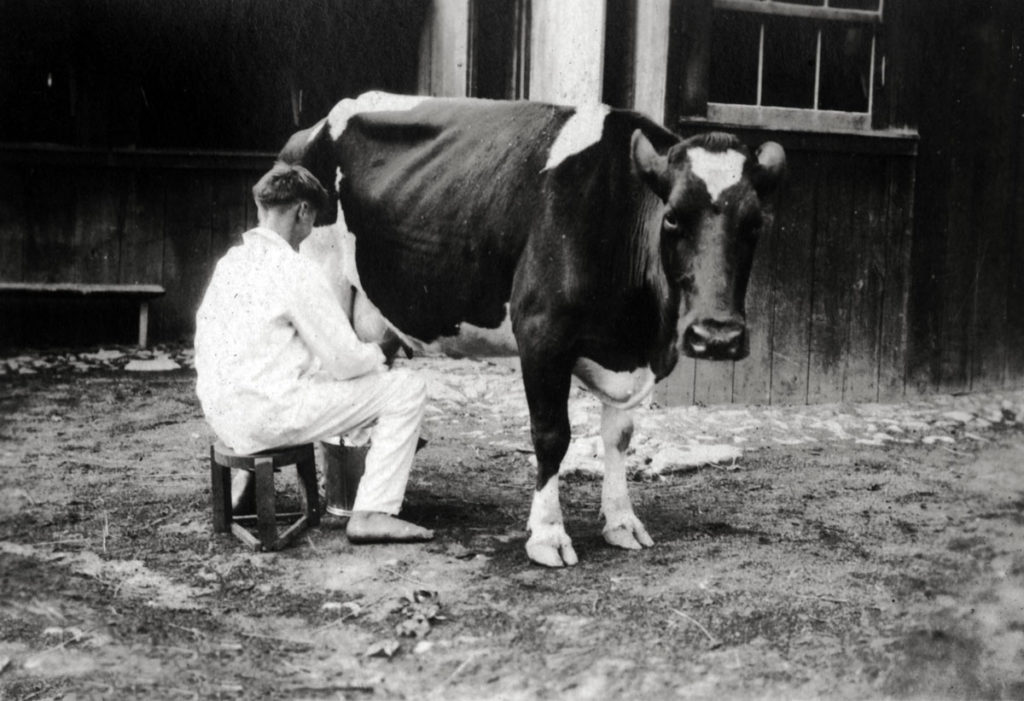

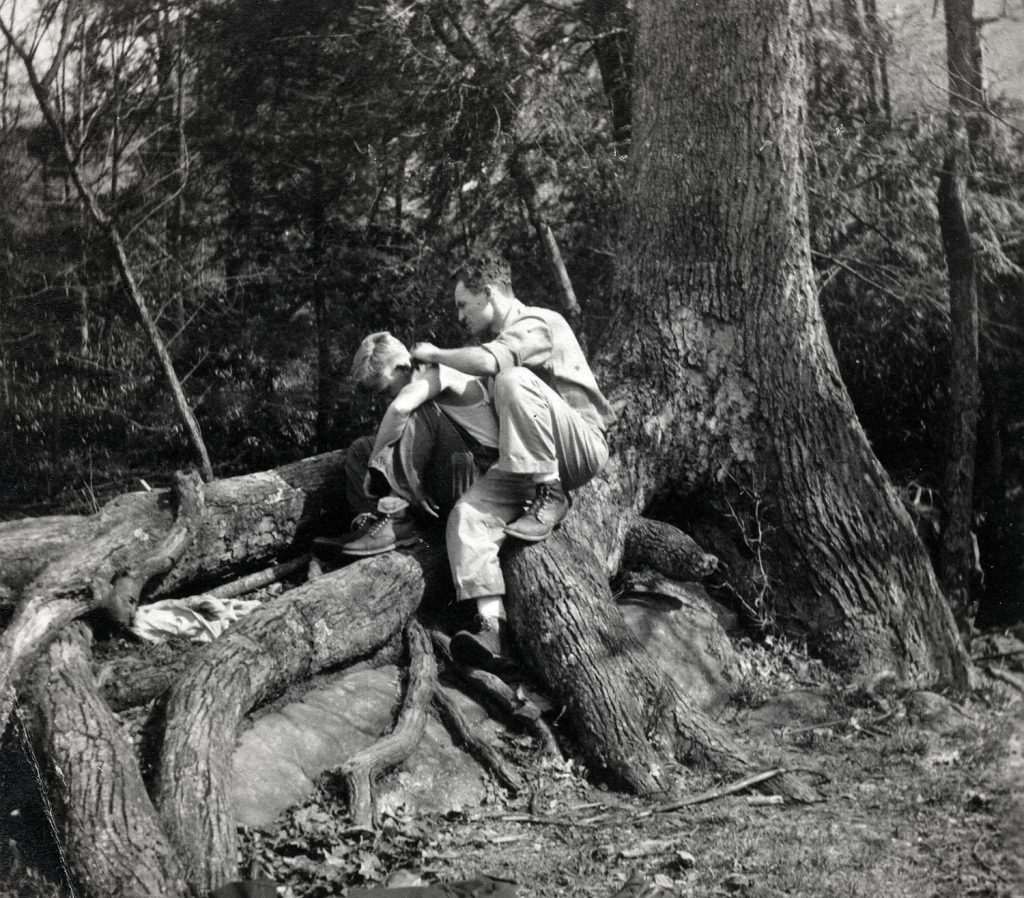

ENVIRONMENTAL PIONEERS at Pine Mountain (left to right) Elihu Afton Garrison, Mary Rogers, Burton Rogers, , [pmss_archives_mr & mrs rogers_DB photo]

SIX years have now passed since this hopeful first blog was written — an homage to the gentle Pine Mountain Settlement School environmentalist, Mary Rogers and pioneers such as Afton Garrison. To those all who gave birth to the Environmental Education program at Pine Mountain and who daily celebrated EARTH DAY. Today, on Earth Day we should be joining in celebrating the more than 50 years of EARTH DAY. We should be enjoying the successes that Mary and others such as the brave international student, Greta Thunberg, who foregrounded our need to re-think our relationship to our environment. We should be living in a world waking to the dangers lurking in our bad habits. Yet, here we are not joined in celebration but distanced from one another and fearful of the world around us — seen and unseen.

EARLIER COMMENTS

Last year seems eons ago as we look out on an entire planet on the edge of an apocalyptic invasion of COVID 19, and now echoes of war fill our press, and vast lands are ravaged by fire, drought, and flood. We are still questioning our over-use of resources and what they have given to our quality of life on this earth, while our plastic fills our oceans. We are in continuous engagement and a fragmented battle with a virus that shouts the message that our relationship with the world is out of balance. It is on that note that this former post is re-posted with the hope that we will continue to move forward, pushed by the new threats to the world that Mary wanted for us all.

Pine Mountain Settlement School will not retreat from the environmental challenges before us ALL. We will continue to remind ALL who will listen, of the legacy that has always been a part of the mission of the Settlement School. For the sake of humanity, we encourage you to join us in the tasks before us; face the challenges and actually work toward solutions that will change our future to one that works for all of us, not just a few. “Some things never change ,” but sometimes they do, because we believe that we are all in this together.

March 21. It was the time of Equinox when night and day are of equal length and when the earth seems to hesitate briefly in its spin as it slips into the longer communion with the sun. In 1983, March 21 had already been changed to April 22 as the universal “Earth Day.” Even earlier, Mary Rogers had set the idea of “Earth Day” firmly in her mind. On March 21, 1983, Mary Rogers slipped into her “sub specie aeternitatis” [Latin for “under the aspect of eternity”] Earthbound, we can know little of her eternity but we have often imagined that it is an exquisite balance of time and space which recognizes the temporal but is not bound to its limits. This is not a story of that enigma eternity but it is a glimpse into part of Mary Rogers’ journey in the temporal world and the wise environmental and spiritual messages she left with those she touched.

The earth swirling with life and framed by the vast blackness of deep space is an iconic image with which we are now quite familiar. The enigma of suspension, the sheer beauty of our home, and the scale of that home in the vast universe is arresting. Suspended in eternity, we are charged to protect this vibrant home. Perhaps this is why the image of planet earth suspended in space has become the symbol of Earth Day. The image reminds us of our fragile existence in an unknown but expanding universe. How remarkable it is that we can now hold that enormous image in our mind’s eye and wonder at it blueness, its roundness, its surface teeming with life — our life. Mary Rogers was, without doubt, entranced by that remarkable image that holds all of earth’s humanity, but more often she was exploring small things; the universe of small life on that shimmering globe. In her diary notes, “Small Things with a Message,” she tells us

MILKWEED PODS

I love milkweed pods. The perfectly overlapped red brown seeds. The gloriously silky plumes, to feel which is one of the great tactile joys of life. Then comes the moment when it all boils up from the pod and flies off into the air —- pure beauty.

I was holding one once and could hardly bear it that I was alone and there was no one to share it with. But God saw it. It was his and he made it and he must have loved to see it — and he let me share that joy.

—- Mary Rogers. Seed Thoughts, 1990. “Small Things With a Message”

LITTLE BROWN JUG

The little brown jug is one of the least attractive flowers in the woods, and hardly anyone sees it as it is hidden beneath dead leaves. You have to clear them off to find it. When you find it its only appeal is its oddity. Its color is drab, the color of red and green mixed together — muddy. It is closed. Its three blunt lobes are the only opening on the small fleshy bottle of the flower. But take a knife and cut it open. It is lined with a rich dark red velvet like an expensive jewel box, and set in the box is a jewel like a tiara with its whitish stamens and anthers. Beautiful! What is the point of this beauty? Few people ever see it. Even the pollinating insects grope around in the dark. What a waste! There are millions of beauties even in this world which are never seen by man, but their creator knows them and has joy in them.

—- Mary Rogers. Seed Thoughts, 1990. “Small Things With a Message”

EARTH DAY BEGINNINGS

The first Earth Day according to many records was conceived by John McConnell, Jr. a peace activist and a Pentecostal from Southern California. McConnell, Jr., born on March 21, 1915, in Davis City, IA. He was the son of a itinerate doctor and was raised in the deeply religious ethic of the family that held to the idea of service to others. McConnell, Jr.’s early job working for a corporation that produced plastics caused him to question his responsibility to the earth and was the beginning of a long journey that sought to call-out actions that endangered the planet and the many lives that shared it. He initiated the idea of “Earth Day.”

It was through the eloquent advocacy of McConnell, Jr. for an Earth Day that the idea found its way onto the 1970 agenda of the National UNESCO conference in San Francisco in 1970. Through McConnell and others, his initial proposal was given serious consideration and an Earth Day Proclamation by the city of San Francisco was made. The date chosen for the celebration of this first “Earth Day” and organized by McConnell, was March 21, 1970. The day was also McConnell’s birthday. The event captured the imagination of many and large celebrations were held in San Diego and in New York, as well. McConnell had opened the milkweed’s pod and the silky plumes were loosed to the winds and the seeds began to grow.

Mary Rogers was, no doubt, encouraged by the work of McConnell, but she had a long head-start on the idea of Earth Day. To her mind, her every day had been an “Earth Day” and the seeds of her journey had been planted early in her life. When she helped to organize the first formal educational offerings at Pine Mountain Settlement School in 1972, it was just ten years after the publication of Rachel Carson‘s groundbreaking Silent Spring (1962), a book that was of profound interest to Mary. Carson’s work was in many ways the beginning of the environmental education movement.

Following McConnell’s launch on March 21, 1970 came an official proclamation from Washington that echoed the sentiments of McConnell but that put a national urgency to McConnell’s idea and that shifted the celebratory date from March 21 to April 22. This date shift was initiated by Senator Gaylord Nelson, an environmentalist from Wisconsin who believed that the new date would allow schools to map their instruction more closely with school calendars throughout the country. The new date would also allow time to work through the national bureaucracy which would fix the event in the national calendar. It would be a bi-partisan effort. Democratic Senator, Gaylord Nelson, with the assistance of Pete McCloskey, a Republican Congressman from California, jointly announced a national “Earth Day” for 1970, and for the successive years. Nelson and McCloskey then recruited Harvard scholar, Denis Hayes as the coordinator of the new Earth Day and charged him with the process of creating an annual “national teach-in on the environment” throughout the country.

LARGEST SECULAR CELEBRATION ON EARTH

In 1970, the April 22 designation of a national Earth Day resulted in massive national demonstrations for the environment and by the end of the year, it had spawned a bi-partisan creation of the United States Environmental Protection Agency and the passage of the Clean Air, Clean Water, and the Endangered Species Acts. The interest and cooperation did not stop at the national level. Denis Hayes built on the national Earth Day planning and went on to found the even larger “Earth Day Network” which was expanded to over 180 nations and garnered the endorsement of the General Assembly of the United Nations. The International Mother Earth Day still remains the earth’s largest secular celebration.

Under President Jimmy Carter, Denis Hayes would later become the head of the Solar Energy Research Institute (1977) (now, National Renewable Energy Laboratory) By 2016 the Federal appropriations for renewable energy resources reflected the national attention to the environment with increased appropriations in solar energy, wind energy, biomass, and biorefinery systems, hydrogen technology, geothermal technology, and water power. Today, those initiatives continue to struggle forward. [Yesterday, April 21, 2020 the price of oil fell below 0.] We still continue to celebrate but our memories don’t always find partners in our actions.

SEED THOUGHTS

Mary’s reflections in Seed Thoughts

Each one of us comes into the world beautifully crafted to give light — maybe as candles or lamps, with wick and fuel, maybe as electric bulbs with the outer container to hold the filament or gas, and we are trying to improve on these by making them make [a] more effective use of the power.

The power: all the candles, lamps and light bulbs in the world are so much clutter unless they are ignited, and if they are damaged through improper use the only thing to do with them is to dump them in the trash. …

— Mary Rogers. Seed Thoughts. “Ye Are the Light of the World”

While the annual efforts of Pine Mountain in building their Environmental Education Program (EE) were modest, they were timely, and over the 47 years from 1972 forward, Pine Mountain has touched the lives of some 3000 students and teachers annually. The history of environmental education at Pine Mountain Settlement reveals an ever-evolving program and commitment. The mission is persistent. The reach of the program is extraordinary. The lives of students, teachers, and other adults have been close to 144,000 [now, many more] over the years of the Environmental Education Program (EE). The longevity of the program speaks to the need for such programs in the schools and the outcomes speak to our future on this small blue globe, called earth.

Mary Rogers was at her core, a very private person. She was never comfortable being called the center of the programming for Pine Mountain’s environmental education, and often pointed to the many skilled EE educators who came and went, particularly Afton Garrison, Ben, and Pat Begley , David Siegenthaler, and others. But no one who knew her will contest Mary’s central role in the formation of the EE program at Pine Mountain. Her work and that of those who followed her at the School provided the first model of environmental education in the State of Kentucky. Her self-taught inspiration and knowledge were recognized in 1988 by the Kentucky Association of Environmental Education which presented Mary and he colleague Afton Garrison their coveted award for excellence in the environmental education field. In 2015, Dr. Melinda Wilder, who sits on the Pine Mountain Board of Trustees was honored with the Lifetime Achievement Award from the Kentucky Association of Environmental Education for her dedication to many of Mary’s aspirations.

The wisdom of Mary may also be found in the creation of the Green Book, the early manual of instruction for the Environmental Education Program at Pine Mountain. It continues to be the underlying structural tool for the ongoing Pine Mountain program. Though major changes have occurred in the standard course of instruction mandated by Kentucky schools, the early work of Pine Mountain helped to guide the restructuring of the state curriculum in the sciences. Going forward, Mary and her successors have continued their advocacy for the environment and have gained new voices and teachers. In her lifetime Mary was a legend, a resource that was incomparable. With her death in 1993, a profound presence and resource went away but not very far.

At the end of her life, following a diagnosis of cancer, Mary looked back at her notes and her diary of written reflections. The brief thoughts she jotted down on that reflection reveal moments of illumination and doubt and deep spirituality. Only a few of these notes of inspiration are shared here. Yet, a large number of her thoughts are, no doubt, carried in the minds of those whose lives were touched by her instruction. The notes, which she titled, “Seed Thoughts” speak of the important revelations that can come at any point in life and that she compared to seeds that grow. As she gathered her many notes to create Seed Thoughts she advised that she selected the ideas that seemed to stick most firmly to her memories and which she “nourished”. She says modestly of those memories

Now, in 1990, I find my mind getting more boring to live with, less tuned in to joy, my memory losing its clarity, my powers of expression somehow blunted, but I want to record some of the incidents which have stood by me as truth… instances I have used in talks given in various places, …These incidents are seeds. Seeds are lovely little things, full of potential, but to realize that potential they must be planted, take root, receive nourishment and grow … to their full richness and glory.

— Mary Rogers, Seed Thoughts, 1990.

For those who knew Mary, it would be difficult to describe anything that she said as “boring.” She shared her enormous wealth of environmental information with such sincerity and conviction and a beautiful British accent, that even the most hardened skeptics were often swayed and rapt attention followed. That attention was found across age ranges as she shared her reflections on nature.

She left hundreds, if not thousands as friends of the earth. Her heartfelt will to bring her audience into her focused spiritual realm was not a hard-shell proselytizing, as often found in the Appalachians, yet it left few untouched by the spirituality of nature’s offerings. By sharing her wealth of knowledge with the many, many children and adults who passed through the Environmental Education (EE) program, —-what she envisioned and fostered at Pine Mountain Settlement School was also a life-lesson in labor, love, and sacrifice. The many years that Mary gave to the Environmental Education Program was unpaid service.

Late in life, she struggled with the idea of service and what it means to share one’s gifts for free. Nature’s gifts are also free, she rationalized. The foundational ideas and inspiration flowed freely from both sources. Her life was also a lesson in values. The environment is not an unlimited free resource, nor are people. Nature and people often come with hidden costs. Educational programming and days, such as Earth Day remind us of our responsibility to give back. And, the greatest “give back” is to be educated in the stewardship of this precious and fragile environment we all share on this great blue planet that freely gives us so very much.

I receive so much in food and housing and care, — but money? How wonderful it would be if like the monks we felt we could live without having to be reimbursed with money. I have a strong inner sense that so many of the evils of the world would be weeded out if people could live their lives for the service they can give for the love of God, and not for higher pay.

Has one the faith to say, “I don’t want a salary.” It seems so lacking in faith not to, and yet getting old may be very expensive if one becomes unable to work, and has to have constant care. One doesn’t want to foist the responsibility for the time spent in care and the money spent on care onto anyone else, yet if one can’t live one’s testimony it is not a testimony, and if one doesn’t believe God is faithful one is faithless. How much should we save for our old age?

—Mary Rogers. Seed Thoughts, “Our Lady Poverty”. “Absolute Poverty”

SIMILITUDES

In February of 1992, Mary was given a book by Phillip Keller, As the Tree Grows (1966). It is as Mary described it is a “similitude.” She says of the Keller work, “He uses the symbols differently but it is a splendid “similitude”. How the living tree and the living person is sustained. Many points amplify what I have already written …” She follows that with her own similitude

In spite of the fact that a few plants still stick with the old way of extracting shreds of energy from the rocks, yet most living things, from the amoeba to the whale, from the algae to the giant redwood, from microorganism to man, all live, grow and function by virtue of the energy the sun supplies through the medium of the plants. We people are only able to grow, to think, to move by virtue of the sunlight collected and stored by the leaves of plants. We are built, we operate by virtue of the sun’s energy present in every part of our bodies. Our coal, our oil, the energies after which we scrabble among the fossil rocks, come from the same source. We wouldn’t need to agonize over our supplies of coal and oil, fossils holding on to their living energy if we could turn to the sun directly, for it is still shining today and every day. More energy reaches us from the sun than we could possibly use.

Often we hunt for spiritual energy from among the fossilized doctrines from the past, and ignore the vast available source of spiritual power with which we are, as it were, bombarded every second of every day, and bleat sadly because we are powerless.

—Mary Rogers. Seed Thoughts, Similitudes – The Sun

Her close friend, Milly Mahoney, teacher and educational leader at the settlement school, described her friend in a talk she gave in October 1998, to the local chapter of the D.A.R. , shortly after Mary’s passing. She quoted some of the many tributes to Mary by her co-workers and her students. For example, a former anonymous staff member of the EE team said, “I never could seem to find the detail, wealth and wonder in a rock, a seed or a flower that Mary could see and illuminate so beautifully with her reverent description and exclamations.”

Few who met Mary will ever forget the messages that Mary drew from the natural environment — this author, included. She drew from a deep well of joy and excitement that never ran dry and that was fed by her deep love of nature and her spirituality. For her, there was an inseparable relationship between ecology and spirituality and it was presented with deeply held conviction. Her spiritual nature was no doubt spawned by her early life as the daughter of a Vicar of the Church of England in the small town of Greenham in Berkshire, England, but it was nurtured by the Eden she found in the Pine Mountain Valley, a location that continues to inspire awe and a sense of wonder and reverence in those who spend time there.

When Mary described the Environmental Education Program in one of the brochures sent out by the School, she quoted from Thomas Merton, “… to help visitors come to see and respect the visible creation which mirrors the glory and the perfection of the invisible God.” Many of those visitors took that advice to heart and one wrote

“Observation, a sense of wonder, a measure of understanding, and hopefully love for the created world may spring from such experiences. A sense of wonder is easier to transmit than pure information and in the long-run is probably the most important thing learned.”

—Anon

Sharing excerpts from Mary Rogers “Seed Thoughts” on this Earth Day, 2019, [2020] we continue the efforts of Pine Mountain to engage a broader audience, fire the imagination, and to remind our friends that decisions regarding the environment have consequences for our fragile and endangered planet and for us. [COVID 19 is our giant wake-up to how rapidly our lives can change] Another gentle reminder is found in an example taken from Mary’s Seed Thoughts and one that she dates to her early childhood. It demonstrates how early she came to her environmentalism and how deeply implanted her connection to the environment remained throughout her life.

THE WILD ROSE

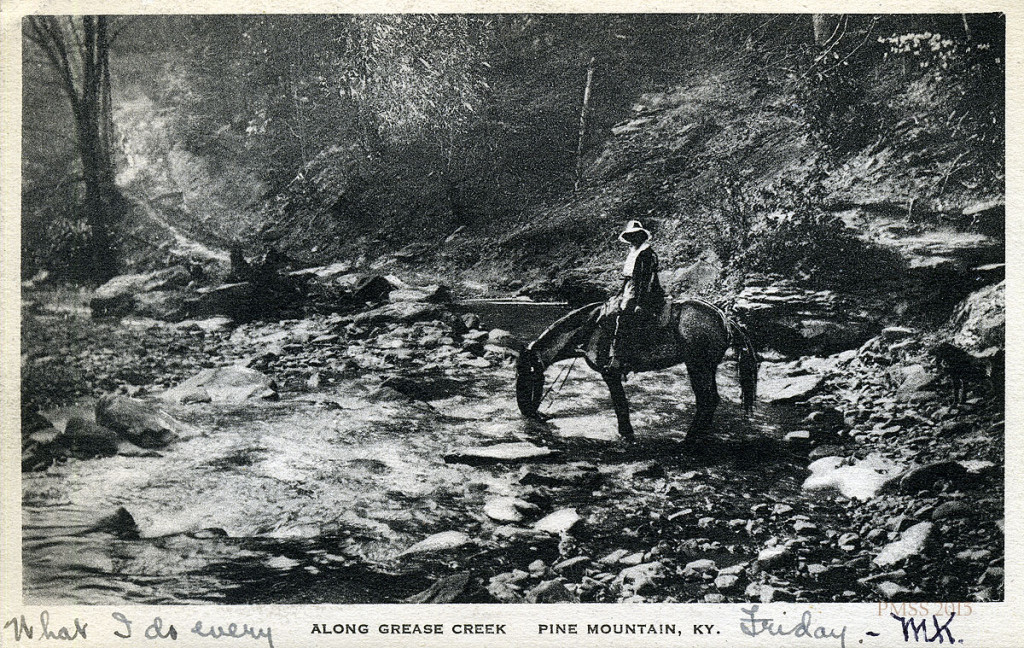

[Photo: Helen Wykle]

THE WILD ROSE

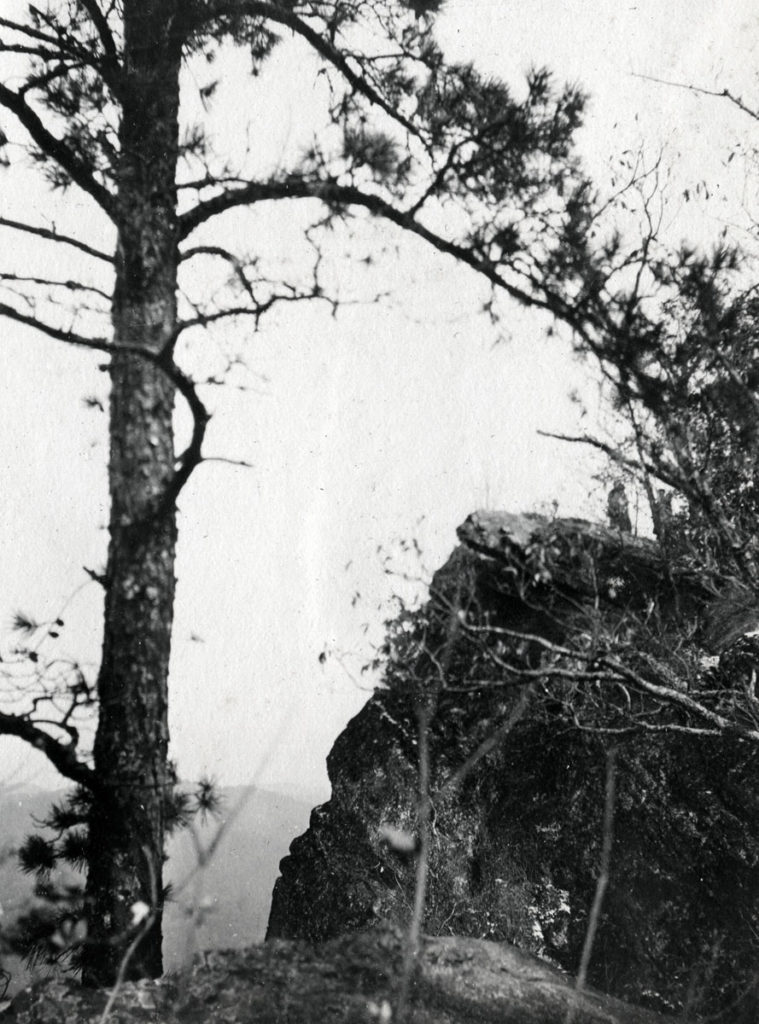

There were not many “pretty” walks round Little Common in Sussex (near Bexhill). We spent summer holidays there at our grandparents’ for many years. At home we were used to roving at will over our Common at Greenham in Berkshire, with its distant views of the Hampshire downs and its heather and gorse expanses with their marshy gullies and surrounding farms and woodlands. We found the Sussex countryside drab, but we were used to going for walks, and one summer when I was 7 or 8 we went for a walk to the “High Woods”, with our governess and our aunt.

I recall it as one of those grey days when nothing looks interesting. As we went along a lane between hedges I stepped to the ditch line to look at a wild rose, pale pink and delicate with its golden heart of stamens. As I looked into its face I found myself repeating lines of a poem I loved ….

“Oh, no man knows through what wild centuries roves back the rose.” [Nor forward]

Suddenly time disappeared and I seemed to be looking down the vistas of eternity.

That moment has stayed with me, and when I later read that Brother Lawrence‘s tree had been a deep experience for him, I recalled my rose. When I saw it the first time I consciously realized that all of time and space experienced as everyday time was unreal compared to this experience. A new dimension was to be with me and stay for the rest of my life. Yes, we were living in the temporal, but nothing can be limited by time. That consciousness has never left me.

I couldn’t put it into words at the time and didn’t want to. It was personal and interior but all-pervading.

— Mary Rogers. Seed Thoughts. “The Wild Rose”

ALL THAT’S PAST

Very old are the woods;

And the buds that break

Out of the brier’s boughs,

When March winds wake,

So old with their beauty are —

Oh, no man knows

Through what wild centuries

Roves back the rose.

Very old are the brooks;

And the rills that rise

Where snow sleeps cold beneath

The azure skies

Sing such a history

Of come and gone,

Their every drop is as wise

As Solomon.

Very old are we men;

Our dreams are tales

Told in dim Eden

By Eve’s nightingales;

We wake and whisper awhile,

But the day gone by,

Silence and sleep like fields of aramanth lie

Walter de la Mare. “All That’s Past” from The Listeners and Other Poems 1912

![Road to Big Log with sheep shed to left and 'Lady' headed home. [Photo: H. Wykle]](https://pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/P1150808-e1555820379540-768x1024.jpg)

Helen Wykle

Easter Sunday

April 21, 2019

SEE ALSO

MARY ROGERS Similitudes

LOREN KRAMER The First Earth Day at Pine Mountain Settlement School

MARY ROGERS Uncle William’s Mandate to Pine Mountain

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION PROGRAM (EE) Guide

Updated HW

Wednesday

April 21, 2020

Updated HW

Wednesday

March 9, 2022

Updated HW

Monday

March 23, 2024