Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series: POSTS

Mountains and

Lucy Furman’s Sight to the Blind

MOUNTAINS

Lucy Furman’s Sight to the Blind is one of the most memorable early works written by a Settlement worker in the Appalachian Mountains. Her process of adapting to living in the mountains of Appalachia was both an inspiration and an education for women of similar interests – those who wanted to find purpose in their lives while challenging themselves in one of the most remote geographies of the United States at the time.

Lucy Furman arrived in Knott County in the Eastern corner of the Central Appalachians in the first quarter of the twentieth century. Her keen ear for speech and her equally observant sight have left her readers, one of the more honest accounts of life in the remote Appalachian mountains near Hindman, Kentucky. Her graphic depictions of the beauty of the physical landscape begin with the eye and ear of an “outsider” but it is soon clear that the term “outsider” meant little to Furman. The bifurcation of “insider” and “outsider” are often reduced in distinction by what some may broadly call our joined “human condition” – something that Lucy Furman knew all so well.

In her writing, Lucy Furman weaves a panoramic picture of early rural mountain living with the briefest of narratives. In her novel, her literary eyes and ears are sharply focused on the life of one mountain woman, whose name is Aunt Dalmanuthy. It is Aunt Dalmanuthy’s “Resurrection” following cataract surgery on her eyes that gives the book its title. The novel is slim and brief in details, but broadly panoramic as seen through this story of “vision.” It is so much more than just another Appalachian hard-luck novel. It is an ode to mountains written in the early dialect of the region but rendered with reverence and remarkable accuracy.

First recorded in the Century Magzine in 1912 and then published in book form by Macmillan Co., the book immediately had a wide audience. The 1914 publication’s popularity was enhanced by the introduction written by the journalist Ida Tarbell, a well-known journalist of the day. Tarbell prepares the reader for the journey Lucy Furman has chosen to share. She maps out the terrain ahead by broadly outlining the remote social setting and appealing to women’s instinct for new adventure in the locked-down world of the early twentieth century.

The stature of Tarbell no doubt boosted the sales of Furman’s book, but Furman’s small book, Sight to the Blind is for the author, Furman, a classic in Appalachian literature. Her small book was written just as Katherine Pettit, the founder of Pine Mountain Settlement School, and her colleagues from Hindman were working to establish a new mountain school in Harlan County, Kentucky. Furman knew Pettit and, like many who had met her through her role in the earlier founding of the Hindman Settlement (W.C.T.U School), Furman was intrigued by such bravery and applied to work with the early School at Hindman.

Lucy Furman, became a long-time employee of Hindman Settlement and a lifetime friend of Katherine Pettit and Pine Mountain Settlement School. Settling in at Hindman, Furman soon became well-known for her intimate literary portraits of eastern Kentucky and particularly of her life at Hindman, the first rural settlement school in Kentucky. First called the W.C.T.U Settlement, Hindman was established by Pettit and her wealthy Louisville colleague, May Stone, who shared many of the same founding principles as Pettit. The W.C.T.U name, or Women’s Christian Temperance Union, paid homage to the school’s primary benefactor. In Furman’s book Sight to the Blind, she captures the essence of the “temperance” mission and gives it an exclamation mark! Her W.C.T.U. admiration was, however, not shared by Pettit, who kept some distance from the tenants of the anti-alcohol manifesto of the W.C.T.U. organization.

But, like Pettit, Furman had a keen ear for the local mountain dialect and culture, and she also had a keen nose. She could tell when liquor was in close company and took some pride in ferreting it out. In Sight to the Blind, Furman uses all her senses in the novel to bring the reader as close as possible to time and place and people in the mountains of Eastern Kentucky. Those who have grown up in the area, as this author has, will quickly sense the reality, the language, and the delight of that early time in the mountains that Furman recalls in her book. Many still living near the waters of Troublesome Creek, or whose ancestors lived nearby, will, no doubt share Furman’s delight and the author’s despair in the habits of the rural community – habits that are a deep silo of literary fodder. The geography and the life of the area agreed fully with Furman and she remained for her lifetime.

THE STORY

In Sight to the Blind, Furman tells the story of a woman whose sight is impaired by cataracts and who rails about her dark world to anyone who will listen. Her plaintive and sometimes raging invectives as the book opens are familiar territory to many who have had similar “quarrelsome” relatives or who welcome a venue to gripe about current status. Aunt Dalmanutha is especially quarrelsome and easily animated by the local preachers as well as the “do-gooders” from the settlement school (Hindman). With the preachers, Dalmanutha is especially cantankerous. Who are they to think that her vision will clear if only she will open her eyes to God as the local preachers admonish. She takes issue with the criticism of compatriots for her ‘ornery life” which they blame on her impaired reception of their Christian way of life. Dalmanuthy is not one to go gently anywhere.

In relating the story of Aunt Dalmanutha and her family, the author reveals many of the classic struggles with faith found in the course of Appalachian mountain living in the first quarter of the twentieth century. Furman graphically challenges some of the basic tenets of mountain preaching with what she experienced in her early urban Settlement Movement life. The local preachers, if any ever read her books, most likely saw her as “ornery” as Dalmanutha. The challenges described by Furman are the familiar challenges that ring throughout early rural settlement school literature and that today resonate so strongly with many women’s issues worldwide. It is this obstinacy of Furman that attracted the author and most likely inspired suffragist Ida Tarbell to laud the all-too-familiar worldwide women’s story, then currently playing out in the mountains of eastern Kentucky.

Ida Tarbell says in the opening lines of her Introduction to Furman’s authorship of two novels

A more illuminating interpretation of the settlement idea than Miss Furman’s stories “Sight to the Blind” and “Mothering on Perilous” does not exist. Spreading what one has learned of cheerful, courageous, lawful living among those that need it has always been recognized as part of a man’s work in the world. It is an obligation which has generally been discharged with more zeal than humanity. To convert at the point of a sword is a hateful business. To convert by promises of rewards, present or future, is hardly less hateful. And yet, much of the altruistic work of the world has been done by one or a union of these methods.

Harriet Butler, to whom Furman dedicated her book, was one of the most beloved nurses at Hindman in its first years. She was later recruited to Pine Mountain Settlement to work with Pettit in her founding years in Harlan County. Harriet helped to found the Big Laurel Medical Clinic, a satellite of Pettit’s newly founded Pine Mountain Settlement School in Harlan County. In Furman’s story of Aunt Dalmanutha, Harriet Butler is clearly the nurse, re-named “Miss Shippen” in her book.

Furman’s precocious book captures the sentiments of local families for their mountain preachers, but through Dalmanutha and in Miss Shippen, Furman strongly questions the ” … cock-sure pride in the superiority of his religion and his cultivation,” seemingly taking a jab at the male preachers who often dominated life in the eastern mountains.

Back to the book, Dalmanuthy, urged by nurse Shippen to seek medical assistance in removing cataracts from her eyes, Dalmanuthy, is finally persuaded by Miss Shippen to pursue medical treatment for her eyes. She travels by train to a Bluegrass medical clinic, and there, the necessary treatment is successful. After many weeks in recovery at the home of her doctor, where she not only has her sight restored but is also given a new set of teeth and, more importantly, a “resurrection” in spirit, Dalmanuthy emerges a “whole” woman.

The story is a short one, but so very powerful in its literary comparison of the struggle of women to cope with Appalachian rural mountain life. The narrative places Dalmanutha as a strk contrast to the affluent life of women in the Bluegrass region. On her return to the mountains, eyes wide open, she is Sight to the Blind personified. The dialect of Dalmanuthy, a woman who was severely impaired and poorly served by her environment due to the limited resources, is reborn powerful, eyes and soul now wide open to the world. The physical limitations of her medical condition are removed, and with the new sight, she then recovers her self-reliance. She falls back into the well-known strong mountain reliance that some mountain women find, and some do not. But, is it enough for Dalmanutha?

The treatment to restore her sight was successful. But she is also reborn. As she travels back to her home in the mountains with her sight restored, she is quoted in the mountain dialect by Furman in what can only be called an Appalachian epiphany

‘But it were not till I sot in the railroad cyars ag’in, and the level country had crinkled up into hills, and the hills had riz up into mountains, all a-blazin’ out majestical in the joy of yaller and scarlet and green and crimson, that I raley got my sight and knowed I had it. Yes, the Blue Grass is fine and pretty and smooth and heavenly fair; but the mountains is my nateral and everlastin’ element. They gethered round me at my birth; they bowd down their proud heads to listen at my first weak cry; they cradled me on their broad knees; they suckled me at their hard but ginerous breasts. Whether snow-kivered, or brown, or green, or many colored, they never failed to speak great, silent words to me whensoever I lifted up my eyes to ’em; they still holds in their friendly embrace all that is dear to me, living or dead; and, women, if I don’t see ’em [the mountains] in heaven, I’ll be loesome and homesick thar.”

Furman, Lucy. Sight to the Blind, New York: McMillan Company 1914. With an introduction by Ida Tarbell.

Ida Tarbell speaks to this transformative event in her Introduction to the book

“A more illuminating interpretation of the settlement idea than Miss Furman’s stories ‘Sight to the Blind,’ and ‘Mothering on Perilous’ does not exist. … That to which we have converted men has not always been more satisfactory than our way of going at it.”

“Our way of going at it” was, in Tarbell’s eye, better seen through the vision of women and not the men who handed down principles, good tidings, and doctrine, but governed by dire consequences from their pulpit and desk. Tarbell, Furman, Pettit, Harriet Butler, and many more women advocated for women to “settle among those who need them.” This was the ethos of the Mountain Settlement Movement that Furman and Tarbell felt at the beginning of the twentieth century and clearly nurtured in women who lived in the mountains of Eastern Kentucky, there to mix and mingle with an ethos so often found in women living in other mountainous regions throughout the world.

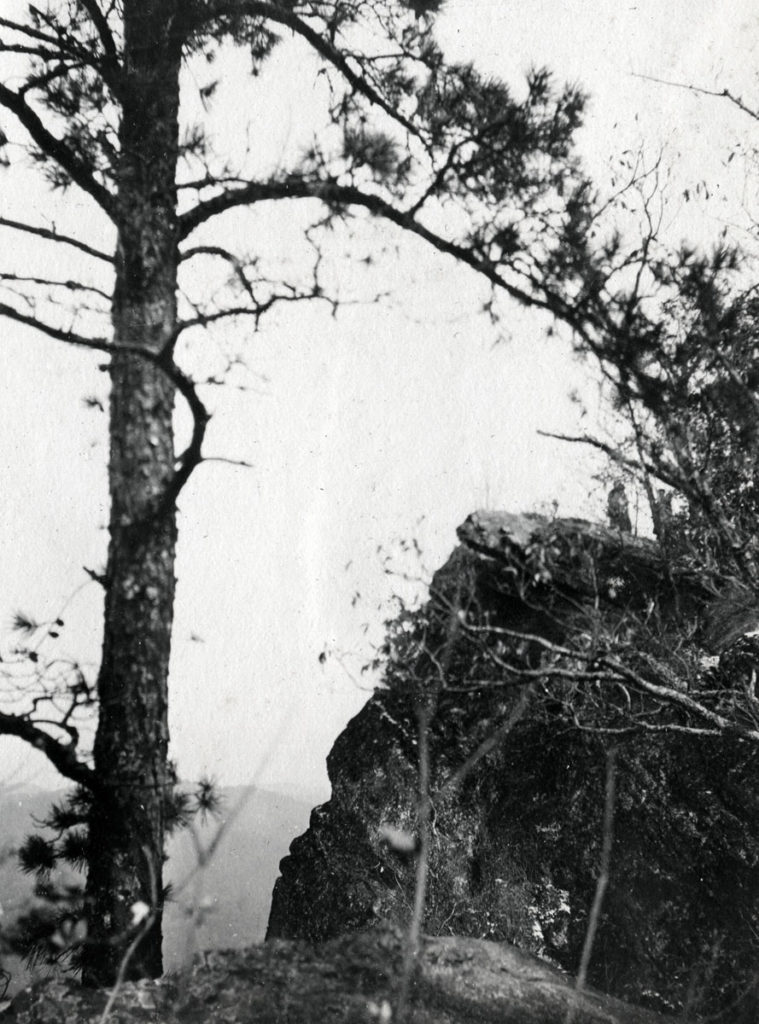

THE MOUNTAINS

In Eastern Kentucky, it is impossible to ignore the mountains. They are both majestic and terrifying. They are sheltering and limiting walls of comfort. They are defined as dwelling places. They face one on getting up and one on going to bed. In Appalachia’s hollows, if the back is turned on one, another is in the face. It is not hard to imagine the dwellers of mountains all nodding their heads in agreement, smiling, or feeling a great lump rise in the throat when thinking about their/our mountains. But mountains defy ownership or specific worship. Go to the top of any mountain in the Central Appalachians, and mountains roll out like an ocean, broken only now by the yellow rock pushing its flat islands of recent surface mining along the horizon.

Mountains are jointly owned. Mountain dwellers hold as tightly to those mountains they can see as well as those they live near or below. Sometimes even those that they cannot see, they know they are there. Those who live “in” the mountains are truly enfolded by the arms, the hollows, of mountains in Eastern Kentucky.

The students who attended Pine Mountain Settlement School and, later, even those students who came to visit in the environmental education programs, carried their own interpretations of “their” adopted mountains. In the early 1940s, a small poem written by a boarding student at Pine Mountain Settlement School described very specifically the mountains she preferred. The poem captures the disjoin of living in a town in the mountains and living “in” the mountains. The writer, Pine Mountain Settlement School student, Mildred Centers, captures the sense of mountain ownership.

I’m getting tired of this place. I don’t like being all crowded together.

I like the good hills. You know — where there is plenty of room for everyone and some to spare.

All I’ve seen are boulevards, streets, avenues, and building. All I’ve heard is the whirr of the motor and the rumble of machinery. And the people — crowded highways, jammed buses, workers packed in the street cars. the shrill voices of men, women, and children while going about daily tasks wear on me.

I like the hills. You know — the quietness, with only the chirp of the birds, the sigh of the breeze, the trickle of the brooks, the rush of the mountain stream. Best of all the quiet moonlit fields where paths lead from valley to valley.

I’d like to take a run up a long steep slope of some hill, find myself a seat on a stone, and whistle some good old mountain tune.

Mildred Centers. Pine Cone 1944 January.

The Geology of Mountains and “Dowbles”

“Pine Mountain is a long and unique ridge in the Central Appalachian Mountains that run through the Eastern section of Kentucky. It extends about 125 miles from near Jellico, Tennessee, to a location near Elkhorn City, Kentucky. Birch Knob, the highest point, is 3,273 feet above sea level and is located on the Kentucky-Virginia border.” (Wikipedia) Pine Mountain Settlement School is positioned near the Eastern terminus of the long-tilted mountain chain.”

The geology of the long Pine Mountain inspired writers, whether as part of the local mythology or within the carefully delineated and many scientific tracts that have been written about the creation and evolution of its singular geology. Mr. Napier entertains us with his “Observations on Pine Mountain“ when he describes the mountain as “…one of nature’s mysteries to be thought over.” He described to Katherine Pettit his view of the creation of the mountain as the remnant of a large river that originated somewhere near Long Island and was gouged out by the force of the water. He describes the Dowbles that one can experience when the ridgeline is walked. Some “Dowbles have retained the water and are treacherous swamps on either side of the mountain. He continues

You still see the signs of great river been flowed north east. You will find swamps, even marshes with more or less water followin’ the old river bed in different places the marshes are so bad that cattle gets in there and dies in the mire if they are not found and helped out. And decayed shells to show they has been a large water course the width of the clifts on each side of the Dowbles shows it has been the banks of the great river. By examinen the rocks on Both Sides of the old river bed it is plain to be seen that river flowed north east. If you notice you will get all kind of water flowin’ out of that mountain and you get the best proof of this by the lime stone in the Pine Mountain. The same lime stone you find several hundred feet below. Elsewhere the upheaval has raised the limestone ledge on Pine Mountain from a level of the lime stone bed found in northern Ky. around Lexington and Winchester.

To read more about Mr. Napier’s observations of mountains and their “upheavals”, visit the following page. Geologists beware … but there is no doubt that Pine Mountain is “… a mysterious mountain that needs to be thought through.”.

Mr. Napier, Observations on Pine Mountain, 1 page

Come for a visit.

Pine Mountain is a long, narrow ridge starting in northern Tennessee and extending northeastward into southeastern Kentucky and southwestern Virginia. Its southwestern terminus is near Pioneer, Tennessee, and it extends approximately 122 miles (196 km) to the northeast to near the Breaks Interstate Park in Kentucky and Virginia.