Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 09: BIOGRAPHY – Staff

August Angel Transcript of PMSS Interview

by Debra L. Bays 1983-01-04

Published 2021-12-21

hw (images) & aae (transcription)

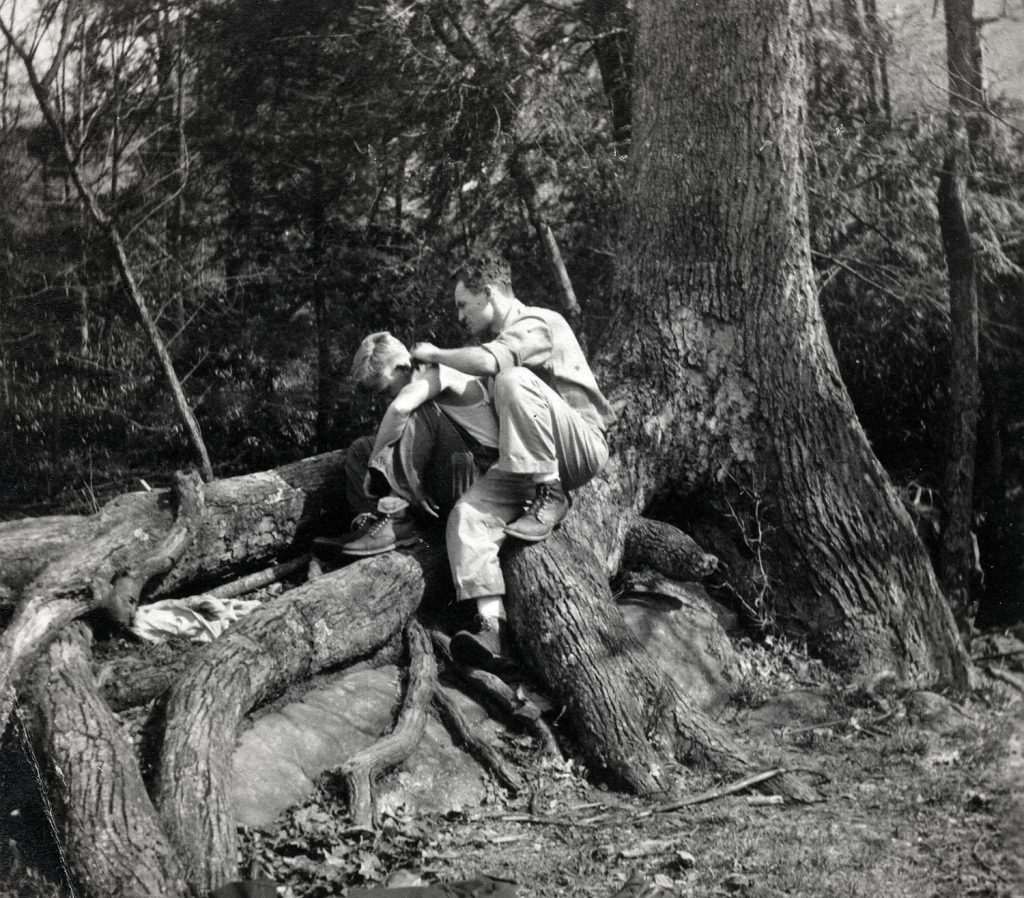

09_2457 August Angel cutting Clyde Blanton’s hair at large poplar on playground, 1930s. [098_IX_students_09_2457_001.jpg]

AUGUST ANGEL Transcript of PMSS Interview

by Debra L. Bays 1983-01-04

TAGS: August Angel, interviews, Debra L. Bays, The Great Depression, Miami University, Alice Carter Shera, Caleb Shera, Glyn Morris, teachers, printing, print shops, Linotypes, school curriculum, cooperative stores, Arthur W. Dodd, coal mining, health services, community activities, Laurel House I, Susie Hall, Practice House (Country Cottage), grades, William Hayes

CONTENTS: AUGUST ANGEL Transcript of PMSS Interview

[NOTE: The following transcription has been edited for clarity.]

angel_bays_interview_001

August Angel, Interviewed 1-4-83 by Debra L. Bays, Pine Mt. Settlement School

D.B.: Today is January 4, 1983, and this is Debbie Bays. I’m with August Angel, Viper, Kentucky, in his office and we’re discussing his life at Pine Mountain Settlement School.

D.B.: August can you tell me about where you grew up and the type of environment you grew up in?

A.A.: Well, I believe I went to high school in Cleveland (Ohio) that would be more like my home and the start of the Depression and there was nothing. I graduated from high school in twenty-seven (1927) and there wasn’t anything to do other than go to school. So, I enrolled at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, and graduated in thirty-two (1932). I had a friend who was very much interested in Pine Mountain, Mrs. (Alice Carter) Shera. She was an art student at Miami University and she and her church had been contacting Pine Mountain, doing social work and sending gifts and so on. And she asked me if I would take her down to Pine Mountain in the summer of 1932 after I graduated because she was being interviewed for a job. She wanted to spend a year or two at Pine Mountain to get away from Oxford, Ohio. So, her son (Caleb Shera) and I drove Mrs. Shera to Pine Mountain and (when) we got there and I fell in love with it. I thought Pine Mountain was something extraordinary. To me it was out of this world. Ours was the third car, I believe, to arrive at Pine Mountain from over the mountain. The third car that came into the area or to the school. Mrs. Shera went off somewhere and her son and I were just wandering around when some young poet (Glyn Morris) came up to me and asked me who I was. I told him my name and introduced the young Caleb Shera. He asked if I wanted to go to school there and I said heck no, I just graduated from college. And he just was amazed or startled or something. Anyway, he asked me a lot of questions and took me around and showed me the place and asked me what I had majored in. I told him that I had majored in science. I had a double major in science and industrial arts. He said we can use you here in both fields. Would you like a job? I said well, I don’t have a job and, yes, I’d like one. So, I got a job. Mrs. Shera also got a job, or a promise of a job, but she wasn’t graduating till that fall. That’s the way we started.

D.B.: Can you tell about the trip across the mountain?

A.A.: Well, it was rough.

D.B.: How long did it take?

A.A.: At that time it would take a good forty-five minutes. Six or seven miles would take a good 35 minutes or an hour to travel over that. It was rough. Not potholes but rocks and just a rough road and hairpin turns.

D.B.: What was your reaction when you hit country on both sides?

A.A.: I was very careful when I was driving, very careful. It was no problem or anything but it was just that I had to watch every foot of the way.

D.B.: When you started at Pine Mountain, what did you teach? Did you teach science and industrial arts?

A.A.: No, I taught general science and biology and we had a lot of time on hand and Mr. Morris, who was director of the school at the time, wanted some printing. He had learned that I could do printing and asked me if I ‘d be interested in starting a little print shop and teaching the kids to do printing for the school and for anyone else. I said yes I would be interested and what he proceeded to do was to buy some hand type and some printing equipment. We went ahead and had five or six students to hand set the paragraphs at a time. We made stories, we made letterheads, and we made printed envelopes and so on. A cheap profit for the school and a good learning experience for the kids.

angel_bays_interview_002

So, Glyn Morris contacted some people in New York City and then we got a Linotype. So we expanded and did quite a bit of printing. When we had the Linotype, that was a big aid to the school because it gave another department (printing) besides wood working and mechanics. There was a chance for kids to get into another field. I believe from the five or six original kids, two are still in printing.

D.B.: Do you know who they are?

A.A.: One was a Gilley (Kentucky) boy but I don’t know where they are. I just hear rumors occasionally that they’re still in printing.

D.B.: What other types of classes were taught at Pine Mountain at that time?

A.A.: Oh, there was the entire (curriculum). It was a good school and it was recognized throughout the country, being innovative. Besides the regular classes, (there was) English and math and science, chemistry, geography, geology, auto mechanics, woodworking, farming. We had extra-curricular activities that were good learning experiences for the kids, like they had their own little store. The kids had their own cooperative store that they ran and showed profit. Really, I believe it was one of the best school set-up for any youngster to attend.

D.B.: Who do you think was most instrumental in setting up that type of school?

A.A.: Glyn Morris, director, and Arthur Dodd (principal and teacher), they were tops.

D.B.: Why did they want the school that’s in the mountains?

A.A.: Just to promote education and give the kids in the mountain area here a chance to learn and to get into some kind of work that would interest them for a livelihood and to aid the area. There was no other (opportunity), there couldn’t be. It wasn’t anything personal or anyone’s (fault?). It was a good learning experience for the kids.

D.B.: Do you feel that Pine Mountain taught the kids about their own community?

A.A.: Yes. Directly and indirectly.

D.B.: Can you tell me in what ways?

A.A.: Directly, they could see that one industry — coal mining, which is the one industry here — was not enough to support everybody. The only thing that most of the boys could do is to go into the coal mines and the girls would get married. That was the only thing. So, the school showed them that there was an opportunity to get into nursing for the girls, get into office work, get into store keeping, get into a variety of work. Whereas it wasn’t just reading and writing and arithmetic up to the third or fourth grade level and just let the kids go back home. Here they had a chance to finish their high school and go on if they wanted to. They could, at that time, back in the thirties, (get) a high school education from a good school (that) was comparable to a college education here at this time now.

D.B.: How did Pine Mountain serve the community as a whole?

A.A.: Their health services really were a big thing. At that time they had a doctor and, under his direction, a number of girls who are student nurses, not nurses but nurse aides and so on who would go out into the community and help with the health problems. That was the big thing then. And then the community would come into the school for various activities: May Day, Fall Fair Day, Christmas activities, Christmas plays. The school then was very popular and very active in the community.

D.B.: Did you often make home booklets to the parents of the students?

angel_bays_interview_003

A.A. : Yes, we made them. Well, I’d spend vacation with some of the students. (I) would go right to their homes and spend two or three days or a weekend or so on with the students.

D.B.: How were you accepted into the home of the families?

A.A.: A teacher in those days was something extraordinary. They welcomed you like you would a doctor in need. A teacher was outstanding because most of the kids would only think of going into the coal mines or going into teaching. That was the only two. Teaching was regarded highly.

D.B.: Now as you look back, can you remember any students that proceeded beyond what you thought they would do or students that really made it?

A.A.: Well, as I said before, I’ve not really kept in close contact but at these homecomings (and) a few events that we had at Pine Mountain in the past five years, then I see the students come back and they’re way above the average of high school kids who graduated in some of the other schools from this area.

D.B.: Have you, could you talk about some of the other teachers in what they taught and some of the extra things they did? Can you remember any of them?

A.A.: All the teachers were on a twenty-four hour basis there. We worked right around the clock. That was our work, that was our home. You could not go anywhere unless you walked at that time and we spent all our time right there at the school. The teacher would have no other interest other than at the school. If they (did), they were misfits. Once in a while, we’d get a misfit: They couldn’t stand the isolation, or the kids. But I can’t say that the teachers did anything other than devote all their time and all their energy to the school, to the students, during a 24-hour-a-day period.

D.B. : Where did you live on campus?

A.A.: I lived at first in a small log cabin. I don’t know if it’s still there. It probably is. Later, I married one of the students (Susie Hall, a 1934 graduate) and we had a home demonstration practice, what we called “practice house (later known as Country Cottage or Model Home). My wife would teach six girls to cook, keep house, and so on, for half a day and then they would go to class for half a day. So, actually, I wasn’t a dormitory parent. When I was single, I lived with another teacher. (We called them workers then). The two of us lived in the log cabin and took care of our fireplace but we ate meals in the (dining) hall (at Laurel House) with the students.

D.B. : Can you describe meal time? What was it like?

A.A. : Enjoyable. It was good. We were always hungry and everybody ate whatever was (served), all the plates were clean. At first we had problems with students who weren’t used to the food that was presented to them. We’d asked them to take two or three bites to taste it. Eventually, they would get hungry enough to eat anything that came to the place, but the big meal was Sunday noon and we would have very good meals once a week. The rest of the time, it was good food, (too), and I believe there was plenty of it, but we were still always hungry. Most everybody was hungry because of the activities.

D.B.: Did you eat family style?

A.A.: Family style. There were eight of us around a table and each table had one worker. We ate at a circular table and we played games. During the meals we’d have all kinds of activities. Each table had their own activity but we’d have all kinds of games and it was a fun gathering time, really. The kids liked meal time.

D.B.: Can you tell about some of the games you played during meal time?

angel_bays_interview_004

A.A.: Well, one of the games was someone would say I am something and then the kids would start (asking questions). The students would ask are you material?, are you living?, are you something in nature? and they would pursue. The only answers they would get from the person would be yes or no. If you’d say are you a living thing, yes I am. Then, are you animal?, are you fish?, and there would be a yes or no answer. You go right down to (specific clues), and it might take ten minutes (or) it might take two or three meal-times for the game to be solved. And you can believe that the kids were (eager) to come (to dinner). If the game was unsolved the kids would be wanting to come to the table to try to resolve that particular game.

D.B.: Do they always sit at the same tables for each meal?

A.A.: No. They would sit at the table for two weeks, then the tables were changed. My kids were moved around. Somebody had some kind of control on their movement. I believe it was (every) two weeks, I’m almost sure it was.

D.B.: How were the kids graded?

A.A.: There were no grades.

D.B.: Could you tell about that and how that works?

A.A.: The kids themselves knew whether they were doing satisfactory work or not. And if they were not doing satisfactory work, the teacher or the worker would work with that student and help them and give them extra (assignments?), until he understood the problem or until he resolved the situation that was at hand. But there were no grades.

D.B.: How did the parents know how their child did in school?

A.A.: When freshmen, ninth graders, came in September (and then) went home for Christmas, the parents knew right quick that they were somebody different. That I can tell you.

D.B.: I’d like to talk about that. How did the students change?

A.A.: Well, most of the students that came were quiet and shy because, (living in) an extremely rural area, they weren’t too used to getting along or meeting a lot of people. Then after a while they made friends and they opened up. We had a lively bunch of kids. A very happy bunch of kids. We had no problems with anyone, really, (except for) an occasional kid. Most of the kids, I would say 99 percent of them, had no problems at all.

D.B.: What type problems did you have out of those who did cause problems?

A.A.: Once in a while you would get a more mature kid and he, I don’t know, he’d be more anxious to get moving faster or to get out or something. Really, there were no heavy problems, (except) somebody who wanted to get out and earn their living, I believe. That would be about all I could say. We had some 21, 22-year-old kids mixing with 16-year-olds and the older (ones) wanted to get out and earn something, I believe. Most of the kids had work (at school) and they were expected to put in so many hours of work a day for which they would get 8 cents, 9 cents, 10 cents, 12 cents an hour, credited to their tuition. The boys did farm work, house maintenance, furnace care, mechanics, or printing. The kids who were in my printing class would get credit for having so many hours of laboring in the print shop, which was also a learning experience. Then some of the kids were milking, others were out in the gardens. The girls were cooking, housekeeping, bed making, window washing, and so on. Everybody was busy all the time. There were activities from five in the morning till eight or nine at night. Then there was study hall for the kids. Then it was time to go to bed.

D.B.: What time did the day start in the morning?

angel_bays_interview_005

A.A.: For some, as early as 4:30. Those who had to milk and cook breakfast, 4:35. Those girls (who) did the cooking at that hour were free later on to either rest or study. The boys that milked and worked around the barn would get up quite early, do their chores, and then they were through. They had their hours in unless they wanted to work extra. We had quite a herd of cows which Bill Hayes will tell you about because he was in charge of it at that time.

See Also:

ALICE CARTER SHERA, Staff – Biography

CALEB SHERA, Student – Biography

AUGUST ANGEL Staff – Biography

SUSIE HALL ANGEL Student, Staff – Biography

PRINT SHOP

PUBLICATIONS

WORKBOOK for Students of Printing

GALLERY: AUGUST ANGEL Transcript of PMSS Interview

- 01 angel_bays_interview_001

- 02 angel_bays_interview_002

- 03 angel_bays_interview_003

- 04 angel_bays_interview_004

- 05 angel_bays_interview_005