Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 17: PUBLICATIONS PMSS

NOTES 1927

March and November

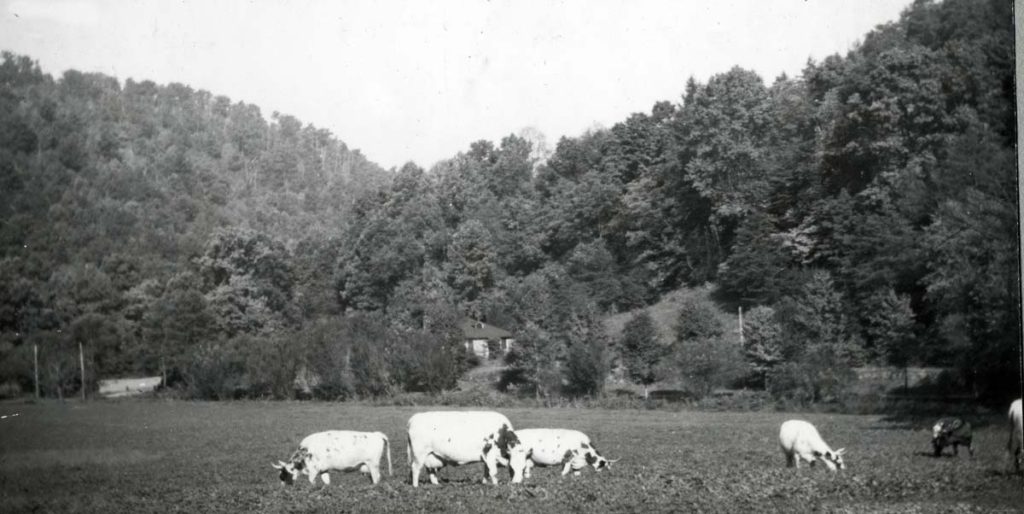

Ayrshire cows and sheep(?) in field, Office in background. [nace_II_album_043.jpg]

NOTES – 1927

“Notes from the Pine Mountain Settlement School”

March and November

GALLERY: 1927 March

Spring came early this year and the team instead of carrying coal for the furnaces is hauling manure for the fields and garden.

- NOTES – 1927 March, page 1. [PMSS_notes_1927_mar_001.jpg]

- NOTES – 1927 March, page 2. [PMSS_notes_1927_mar_002.jpg]

- NOTES – 1927 March, page 3. [PMSS_notes_1927_mar_003.jpg]

- NOTES – 1927 March, page 4. [PMSS_notes_1927_mar_004.jpg]

TAGS: NOTES – 1927 MARCH: storytelling, John Shell, Henry Shell, folklore, Baron von Munchausen, Girls’ Industrial Building, weaving, woodworking, one-room school, Dancing Ladies, gardening, Jane Nolan, Dorothy Bolles, Cecil Sharp, Mary Cunningham, Evelyn Wells, Abby Winnie Christensen, National Information Bureau, band instruments, sword dancing, Federated Women’s Clubs, Isaac’s Creek

TRANSCRIPTION: 1927 March

P. 1

NOTES FROM THE

PINE MOUNTAIN

SETTLEMENT SCHOOL

PINE MOUNTAIN * HARLAN COUNTY * KENTUCKY

Copyright, 1927, by Pine Mountain Settlement School

Volume II MARCH, 1927 Number 7

A NEW bear story has just come our way, the hero of it that John Shell who was once reputed to be the oldest living person in the world. Though thirty years and more were cut off his age when dates were verified, this tale of his boyhood goes back beyond 1840 when settlers in this country were few. Game of all sorts abounded and a good hunting dog was a prize possession. Our narrator had heard the old man tell this tale time and again, to the huge relish of both. Here it is as we heard it: “When Johnny was nigh grown he and his pappy set out with their dogs one mornin to look at two bar traps they had set. The traps were far apart and they thought to save time by each one takin a trap. His pappy’s dog was the smartest and the old man made Johnny swap dogs with him for safety. The boy had only one shot left in his gun and his pappy reminded him again of his old hunter’s rule never to shoot his last shoot fur away from home for fear he might need it a heap wurser on the way home. There was no bar in the trap but the dog growled so Johnny knew there must be one mighty nigh. He bade the dog hush and of course hit did-hit was an awful good dog to mind. He started up the holler, put his hand on the end of a great log as he passed it and up from the other side of it a big bar jumped and made for him. The dog weren’t goin to see Johnny hurt. He flew at the bar. Next thing Johnny heard the dog’s shoulder bones scrunchin in the bar’s jaws. That made him so mad he throwed down his gun and made at the bar with his knife. They hugged up and Johnny stabbed that bar fourteen times afore he kilt him. The bar he raked his chest with his paw, mighty nigh clawed open that vein in his neck. The old man showed me the white scar where his claws gouged him. He never had no notion of using that gun. His pappy had his mind fixed on allus savin the last shot to go home by. When Johnny went home with his gouged-out chest pappy was rearin mad because he had let the dog get hurt! That dog, damaged up as he was, was a pyure dog! The old man traded him, lame shoulder and all, for seven hundred acres of land.”

The old tales in the mountains are worn down through many repeatings to the bare essentials, like the ballad tunes that flowing through the centuries have kept only a crystal clear beauty. These folk tales have no unnecessary phrases, no interpolated descriptions. The few words necessary to tell them are strong with the shrewd humor of plain folks. The audience often knows the tale ahead, just where the laugh should come. But the tales are all the better for being familiar. Perfectly simple, they are never dull and threadbare, rather like well-worn gold coins passing from hand to hand, precious to each holder.

Here is one of a scary feller who thought he ought to sit up all night with a sick neighbor. “He couldn’t git started till atter dark and havin no lantern he was oneasy in his mind because there was a old wild boar loose in the mountains that had been bothering folks a heap. He allowed he mought meet up with it. Shore enough, he hadn’t got down to the Bull Horn Ford afore he heerd a gruntin and a growlin and a stirrin in the…

[1]

P. 2

…leaves and he mighty nigh knowed it war the old boar. He made for the nighest tree and clumb up it. Hit was so big he couldn’t git his arms around it and so high to the first limbs he couldn’t climb up to ’em. He helt on as long as he could. When there warn’t no more noise down below he hoped the old hog had gone plum off and he let hisself down. He hadn’t no more than teched the ground when the gruntin and russlin begun again and up he clumb. He helt on till he allowed it war gone and then he drapped agin. Up starts the hog agin. Well sir, they might have kept that up all night if Henry Shell hadn’t come by with a light. Old Joe was mighty weak by this time and proud for help to save him from bein all tore up by the boar when he couldn’t holt on no more. Well sir, you know when they found hit hit warn’t no boar at all but a leetle old shoat couldn’t a weighed more than sixty pounds, what had hurt hit’s hip and couldn’t get along. Jes for that leetle thing Joe had wore the moss and bark offen the tree and all the hide offen his legs. You can see the tracks on that tree yit whar he went up and down.”

Here is one almost as famous as the Baron Munchausen tales. “I was a-goin to the store for some coal oil through a leetle piece of woods when all of a suddint I seed right a-fore me a wild cat a-settin in the road. I turned round to run back and thar behind me sat another. I run up the hill a piece and stood a-watchin, allowin I’d go home fust chanct, when them two cats begun to growl and then to spring and claw at each other’s hide, ajerkin out the fur. They fit and fit and every time they’d jump at each other they’d rise a leetle higher. Purty soon they ris plum out of sight and never come down. Well I went home, but the next day I passed that way agin and the fur was still a-fallin.”

***

AT THE Girls’ Industrial Building the engrossing interest just now is the working out of the double-faced or “winter and summer” weave. A neighbor has just finished a lovely coverlet that the girls are striving to emulate. Second only in its absorbing qualities is the elusive “blue-pot,” the despair of the disciples of the ancient art of home-dyeing. Standardize it as one may, it never seems to “come right” for the novice except by chance. How we envy the magic touch of Mrs. Jane Nolan, who was taught to “set up” the bluepot by her grandmother and whose knack for securing the right shade of blue seldom fails.

***

PROJECTS in our woodworking department have never been artificial, for the boys have learned the use of tools and the qualities of our beautiful native woods through making the necessary furniture for our buildings. The shop has become a real factor in developing their aesthetic taste, and now many of them are putting in every spare minute, making things to take home. Some of them are far past the stage of picture frames, stools and candlesticks, and have made chests, armchairs, desks, even inlaid checker tables and carved strong-boxes for their treasures. We suspect that the boy who has made a beautiful walnut table for the library, a fine desk, or chest of drawers to fit out a room in the School will see furniture with different eyes for the rest of his life. We should like to turn some of our cabinet-makers loose in the American Wing of the Metro- politan Museum for an afternoon.

***

A COMPOSITION: “When I grow up I am going to marry if I can. I am going to be a farmer if I can and raise stock and folls. I am going to try to live in a clean house and a clean life and be a Christon.”

***

A RED-HOT stove in the middle of the room, encircled by a dozen or at most a dozen and a half boys and girls each with a book; the teacher standing rigidly behind his table; windows closed, though often the door stands open admitting a chilly draft; no books except the texts; no pictures; only a few square feet of blackboard — such is the picture of the country school in December.

When a class is called — a race for the front of the room. Is it a grammar class? “John talked to him and I” passes as correct. Is is arithmetic? The laborious method of long division is used with “5” for a divisor. Is it a reading class? Oh, the painful process…

[2]

P. 3

…of jerking out a series of words with the aid of the teacher, who sometimes doesn’t know himself! One teacher told the children when they didn’t know a word to skip it and go on. The idea of reading words in groups is utterly foreign, and phonics quite as unknown to teacher as to pupil. The recitation is broken by the continuous snap, snap, snap of fingers as continuous wants are made known by those about the fire, the thump, thump, thump of heavy shoes on the rough floor as a child makes his way forward and thrusts the book with a finger on the unknown word in the teacher’s face, or the same thump, thump, thump as the restless children tramp to the common pail with its common dipper.

A dozen or a dozen and a half children — this in January. The roll records thirty-five, forty, fifty, or even sixty for July, the first month of school, with a steady dwindling to the close. The excuses for the dwindling are many — sickness, high water, getting the family wood, bringing in corn — but the most serious reason is the entire unattractiveness of school. Many, perhaps most teachers are only concerned to get in the required six hours.

***

COULD any normal child be expected to make special effort to attend a school such as a recent visitor here describes? The teacher was a young mountaineer, short, crooked, with black towsley hair and a pompous strut as he stalked back and forth, stick in hand. Six small children were solving problems at the board. “Read your problem — read it — read it,” he shouted in a high-pitched voice. “You stay out of school and come back and expect me to tell you everything. I won’t do it. I don’t have to. I get my pay just the same whether you come or not. I’d get my pay if I came here and set down,” and he slapped Sally on the head and punched her with his fist. “You know how to get it,” and puzzled little ragged Sally made figures frantically until he turned away. The next victim was a little boy of perhaps ten years with a thin little voice as thin and frail as himself. “Hurry up, Denver,” this accompanied by a squeeze of the neck and a slap on the head. “Sally,” in a deep growling long-drawn tone, “cost of a pound and a half of butter at forty cents a pound?” Silence. “What does a half a pound cost?” “Twenty cents,” replied Sally confidently. “How much is a pound and a half?” Profound silence. “Sally! How much is one egg if a dozen is twelve cents?” “One cent.” “All right. How much is five eggs?” “Five cents,” says Sally. “Pretty cheap, aint it?” said Mr. B. “Well, how much is a pound and a half of butter? Denver,” he screamed, “five times five?” and he knocked Denver’s head against the board. “John aint done it. Now you get that,” and both sides of John’s head received cuffs. “Sally, Sally, a pound and a half of butter. Don’t stand on a pound and a half of butter.”

The group of seven about the fire had been whispering slyly and glancing furtively out of the corners of their eyes. Here a little fellow from the circle tiptoed to the teacher and said something in a low tone. “Come here, Ezra.” A round-headed, close-cropped little fellow arose and went tremblingly to the teacher, who asked, “What’d you spit in Roy’s face for?” Before the child had a chance to answer the switch descended. Ezra went to his seat, rubbing the back of his head. A half hour later he stepped to the teacher and the stick descended on another boy. Ezra went to his seat grinning. He had been revenged. The next victim was a tall, fair-haired girl. “Interest on what?” asked Mr. B. “A dozen toe-nails or Sally’s pound and a half of butter?” and he smiled amiably at his own wit, After dismissal the children, bare-headed and with no wraps, seated themselves on the rocks outside to munch at leisure their cold corn-bread, though it was a January day and the streams were partly frozen. Of this school a parent had said, “Mr. B. is just a boy and hit’s his first school, but he’s had two years at normal school and he’s doin jes fine.”

However, even experienced teachers depend on the switch. A man who had taught for twenty years told us at a teachers conference that he had dropped out more and more every method of discipline except whipping. “I whip my children, indeed I do,” he went on. “It’s my custom to line them up right after the devotional exercises and sometimes I have half a dozen great big boys and girls just the sweet-hearting age.”

It is encouraging to find occasionally a bright picture. For example, it is a joy to…

[3]

P. 4

…visit the school of a little Pine Mountain-Berea product. The sunshine streams through the windows lighting up a well-ordered room with desks neatly arranged, and maps, pictures, and gay health posters on the wall. There is even a small library and some modern devices for busy work. The quiet little teacher always welcomes suggestions. The children are diligent and contented. Three of her big boys have gone on to Berea this year. Or again, the success of a “fotched-on” teacher is proclaimed by the fact that whereas her record book showed 120 tardy marks for the first month of school, only nine were recorded for the next, an unheard-of record, all in spite of the fact that she had to answer in the negative one of her little girls who asked her if she was a “whoppin” teacher.

These schools challenge the best intellect, tact, and skill. They need, too, authoritative supervision by practical, competent, resourceful personalities; with it we might hope for miracles in the entire life of the mountains.

***

WE SHALL try to organize a band at Pine Mountain in the fall. It would be a great help if any of our friends could send us discarded but good cornets, clarinets, trombones, or piccolos in B flat, low pitch.

***

WITH April just around the corner, the School is fluttering with expectation of the annual visit of the Dancing Ladies. Miss Dorothy Bolles, a pupil of Mr. Cecil Sharp and a teacher of English Folk Dancing in Boston, and Miss Mary Cunningham, such an accompanist as could set the world dancing whether she plays the piano or the concertina, have spent the last four Aprils with us, making every recess and every Saturday night party a celebration and yet contriving so that the gayety of many small good times shall give training enough for a beautiful festival on May Day. There are country dances for four or six or eight, and delightful longways “for as many as will,” after the generous style of the old Virginia Reel. The very names lure awkward youngsters to join in the fun — Nancy’s Fancy, the Black Nag, the Old Mole. There are sword dances for big boys who come to practice tired from the field or work shop and go through the amazing evolutions with incredible dash and speed; and morris, with its more difficult step, for some of the best dancers. Of course dancing is an all-the-year pleasure for us, with Miss [Evelyn Wells] and Miss [Abby Winnie] Christensen to teach classes and manage parties, but in April Pine Mountain attains real unity. Then boys at the exasperating age would rather dance than plague the little girls, and everyone is absorbed either by the delight of motion or by the effort to achieve a greater beauty in a step or figure. Last May a group of boys and girls danced before the Federated Women’s Clubs of the State and were given really ardent applause. Perhaps the ladies felt as we do at Pine Mountain that modern social dancing has nothing to compare with this old dancing in gayety, variety, and beauty. No wonder that letters from former students so often say “the worst thing I miss about Pine Mountain is the dancing!”

***

SPRING came early this year and the team instead of carrying coal for the furnaces is hauling manure for the fields and garden. The workshop boys have left off making tables and chests of drawers for the new Big Laurel house and are digging a new shorter channel for one loop of the creek which over-flowed part of the garden in the big tides. Country folk are looking for a sunshiny day to gather wild greens, a longed-for relish for those who must live all winter on dried, [pickled], or buried fruits or vegetables. At dinner the other day we rehearsed the spring greens that might go into the gatherer’s basket — crowfoot, speckledick, puccoon leaves, poke, plaintain, lamb’s quarter, cow’s glory, dandelion, wild mustard, elder leaves, goose’s tooth, bear’s lettuce, shone, creese, sissle, lady’s thumb, pepper and salt, wild turnip, dock and woollen breeches. A blend of any half dozen of these will make a bait of sallet indeed. The very names make folks’ mouths water.

***

THE National Information Bureau, which for years has endorsed the Pine Mountain School, announces that owing to a change of policy it no longer considers the endorsing of schools its province; but it consents to furnish any information about the School to inquirers.

[4]

The Marchbanks Press, New York

GALLERY: 1927 November

Meals at Pine Mountain cost thirty-three cents a day per person, and it requires great skill and ingenuity to serve interesting food for this sum of money, in a place where there is no ice, and no market; where the fresh meat is local beef or pork possible only in the cold weather.

- NOTES – 1927 November, page 1. [PMSS_notes_1927_nov_001.jpg]

- NOTES – 1927 November, page 2.[PMSS_notes_1927_nov_002.jpg]

- NOTES – 1927 November, page 3.[PMSS_notes_1927_nov_003.jpg]

- NOTES – 1927 November, page 4.[PMSS_notes_1927_nov_004.jpg]

NOTES – 1927 NOVEMBER: taxi driver, storytelling, William Browning, Ayrshire, Joy Stock Company, farming, ‘Sun Up’ play, ballads, Cecil Sharp, Maud Karpeles, meals, piano, weaving, Luigi Zande, Mrs. Martha Burns, Cavalier’s Ruth III, Elizabeth Hench, Mary Rockwell Hook, Celia Cathcart Holton, Colonial Coverlet Guild of America, Fireside Industries Department, Ruth B. Gaines, food menus

TRANSCRIPTION: 1927 November

P. 1

NOTES FROM THE

PINE MOUNTAIN

SETTLEMENT SCHOOL

PINE MOUNTAIN * HARLAN COUNTY * KENTUCKY

Copyright, 1927, by Pine Mountain Settlement School

Volume II NOVEMBER, 1927 Number 8

[The Taxi driver, as he brings two workers over a newly opened road on Big Black Mountain, tells a tale of his boyhood in the mountains.]

ONE TIME when I was just a lad, a man over Virginia come along and asked me and another boy to help him go and take some cows across Black Mountain to his mother. Hit was November, and about noon, and after a little snack to eat we started off. When we come to the top of the mountain we found snow, though we hadn’t seen none that year down below, and hit was hard going. We missed the trail, and went right through the woods, and we kept on a-goin’ down the mountain, right down that branch we passed back there, till along about one in the morning we begun to see a light a- glimmerin’ way down below. When we come nearer, we see that hit shined through the chinks of an old log house, and hit was fire-light. Hit looked mighty good to us boys! We had started when the day was warm, and hadn’t coats over our shirts. We had sweated and then froze, and we was awful cold. When we come to the cabin, the man pecked on the door and a woman inside says, Who’s that?” “Hit’s me.” “Is hit you, John?” “Yes, hit’s me.” Then she come and opened the door a crack and looked out, and we could see that good fire on the hearth, but we had to just look at hit while her and John talked some more. He says, “Well, Maw, I’ve been fixin’ to come for a long time, but my baby died and we had to bury hit.” “Didn’t know you had ary baby,” said his mother, and then she said, “But that ain’t nothin’; we buried your brother Rufe today.” And all he says was, “Humph!”

Well, finally John says, “We’d like mighty well to warm by the fire, Maw,” so at last we got to come in, and the old woman she says, “They’s some corn licker behind the chimney,” but John says, “Fix us some supper, Maw.” “Well,” she says, “We haint got nothing left to eat, they’s been so much company today, with the burying and all.” But John, he insisted, so she called the two girls from the back room, — great, long-footed gals they was, old maids, — all of twenty. They fixed the supper. And I want to tell you what-all we had to eat. There was a ham that hadn’t hardly been cut into, and biscuits as big as your fist-es, baked in a Dutch oven, and they was a platter of slabs of honey, every one of them weighing as much as five pounds!

Then we went to bed. I guess them gals had to sleep before the fire the rest of the night, for they gave us the bed in the back room. I can remember now how the feather mattress was so high, you had to climb into hit with a ladder.

Yes, folks lived well then, when they could hunt, and had plenty of land. But they’d made six thousand dollars gathering sang (ginseng) and the old man was off at the very time, buying a farm in Tennessee. The old woman talked about moving. She says, “They say down there on that farm hit’s so level, you can see a man clear from one end of the land to the other. I’ll be mighty sorry to leave these grand old mountains, though I haint never seed nothing but trouble and satisfaction all my life. Trouble and satisfaction,– that’s all there is to livin’.”

[1]

P. 2

WHILE good weather lasts, our two squads of boys are working hard outdoors. Mr. [William] Browning‘s boys, working on the farm, are burying our 9,000 cabbages and our 7,000 heads of celery, gathering fodder, and terracing a waste hillside to prepare it for grazing purposes. Mr. [Luigi] Zande‘s boys have tiled and filled in a long ditch, have helped finish two new rooms in the loft of the Model Home, and are now working on a small addition to our Infirmary, so we may have a much needed receiving room and an office for dressings and treatments. A one-room “pole house” is being put up for Mrs. [Martha] Burns, who is in charge of our dairy and poultry.

***

AN EPIC event of the summer was the arrival of a pedigreed personage, Cavalier’s Ruth III, the Ayrshire heifer given us by the Joy Stock Company. The cow is familiarly known as Joyce, and it is her duty and will be that of her daughters to help us realize our goal of a quart of milk per day per person. The Joy Stock Company is directed by Miss Elizabeth Hench, Secretary of our Board of Trustees, and has for some years supported a cow at Pine Mountain.

***

FOUR OF our board members, Mr. D. D. Martin, Miss Elizabeth Hench, Mrs. Mary Rockwell Hook and Mrs. Celia [Cathcart] Holton, gathered at Pine Mountain for a meeting in May. They really became acquainted with the workings of their school, for they visited regular classes, observed the industrial work, — cows being milked, dishes being washed, meals being cooked and clothes being washed. Our one real function for them was a production by the High School of “Sun Up,” — a mountain play acted by a cast of mountain children. As naturally as the Widow Kagel wore her own grandmother’s sunbonnet and tight-waisted dress, did the whole cast assume the roles of the mountain characters and create an atmosphere that was not only convincing, but profoundly touching.

***

ONE OF our visitors last summer made us acquainted with a whole family of rare creatures who share Pine Mountain with us. “Sallie” is no longer simply a girl’s name here, but the affectionate diminutive for a small rare being who lives under the bark of old logs and is known formally as Aneides aeneus of the salamander family. This shy individual had escaped our acquaintance till Mr. Clifford Pope of the Department of Herpetology of the American Museum of Natural History came to dig him out of his quarters and study his family habits. Indeed, the whole world of naturalists knew, up to this summer, of only ten individuals of his species elsewhere on this planet, one of whom had been seen here years ago. Mr. Pope and two boy assistants from the school sought out damp spots, bark just loose enough on the log to allow crawling room for a small fellow barely a finger long, and they kept at it for ten days till some ninety-eight of the green and black salamanders were discovered and enough of the eggs to furnish material for study. Mr. Pope, a true scientist, rather than a popularizer of scientific information, profoundly impressed us with his intent and interested observation of nature. He disposed of several bogies,– fear of blue-tailed lizards, for instance, and of hoop-snakes that might roll after us, and he aroused tolerant, if not cordial feelings in us for harmless snakes. This helped us to proper behavior when, three days after he left, we discovered comfortably arranged in a desk drawer a mountain black snake he had collected for the Museum, and which had to his regret eaten its way out of the confining sack to liberty!

Mr. Pope’s visit was one event on our calendar of natural history. Another was the arrival of Mrs. Roberta Parke, formerly of the Masten Park High School, Buffalo, to teach Biology. Her combination of fine teaching skill and great personal enthusiasm has stirred the whole school. Even the smallest child collects caterpillars for Mrs. Parke. Conversation at meals ranges over such topics as the stomata of leaves and the difference between bugs and beetles. In short, we are all thrilled by being awakened to the wealth of the world about us.

***

WE HAD a renewal of great memories this October in a visit from Miss Maud Karpeles, who came here ten years ago with Mr….

[2]

P. 3

…Cecil Sharp when he was collecting ballads. At that time, besides singing many of his mountain tunes for us, he introduced us to English Country Dances, which have formed an important part of the recreation of our young people ever since, and we were able to show him the Kentucky Mountain Running Set, a dance whose discovery he set great store by, and which hundreds of English Folk Dancers have enjoyed ever since. We can scarcely believe our good fortune, that here in this far-a-way corner of the world, we should have seen Miss Karpeles, one of the most beautiful English Folk Dancers, doing Morris jigs, — Jockie to the Fair, Lumps of Plum Pudding, The Princess Royal — and heard her sing some of the unpublished songs that she and Mr. Sharp collected in the Appalachians. We sing ballads, we collect ballads, we devote ourselves to folk songs, yet Miss Karpeles held us spell-bound as if we were hearing such songs for the first time. There is no putting into words their beauty nor the impression they give, as words and tune unfold, of centuries of human life flowing past.

***

MEALS at Pine Mountain cost thirty-three cents a day per person, and it requires great skill and ingenuity to serve interesting food for this sum of money, in a place where there is no ice, and no market; where the fresh meat is local beef or pork possible only in cold weather. Miss [Ruth B.] Gaines, who has been with us thirteen years, has developed so unusual an ability in dealing with these circumscribed conditions that she has often been urged to get up an institutional cook book for others up against such difficulties as we have. Here are her menus for yesterday and today:

BREAKFAST

[1] Oatmeal, stewed prunes, biscuits with butter substitute

[2] Cream of wheat, cocoa, biscuits with butter substitute

DINNER

[1] Chicken and rice loaf, creamed turnips, chopped cabbage and celery, soup beans, cornbread, chocolate pudding

[2] Creamed tuna fish, sweet potatoes, green beans, cold slaw, cornbread, jello

SUPPER

[1] Rice and milk, cornbread, canned pineapple

[2] Potato salad, cornbread, one-egg cake

Two children who went to school in Michigan this year, have written back to get Miss Gaines’ recipe for cornbread. Our “main dishes” for dinner are wonderful mixtures of fish and potato, rice and tomato, cheese and bacon. Variety at breakfast comes with fish-cakes, potato cakes, French or cream toast, and at supper with a vegetable or cream soup, a bean or potato salad.

***

WANTED: An upright piano in good condition. We have many girls taking music lessons, who are willing to put their precious daily hour of free time into practising, and the problem of fitting them all in to practice periods is one we must soon solve. Freight and Express comes to us in good condition, addressed Pine Mountain Settlement School, via Putney, Harlan County, Kentucky.

***

MOST WEAVING rooms for hand-made products are interesting places, but ours at Pine Mountain has a peculiar charm, like a corner of a museum come to life, or a spinning house of colonial times. In the wide world of fascinating hand-made things, we have chosen for our part to keep alive the arts of colonial days that had not quite disappeared when we came here; — to use really homespun yarn, to dye with madder, indigo, walnut, willow, broom-sedge, by the old rules, avoiding brought-on, mercerized threads and chemical dyes, to make blankets and coverlets after the old patterns that came in with the generation following Daniel Boone. Yes, Macy and Wanamaker now sell machine-made coverlets, extremely pretty, but the market is steady for hand-made spreads dyed with colors that grow lovelier with age, like those of old Persian rugs, and the Fireside Industries Department has hard work to keep up with orders. Why let an indigenous art die out? Too many lost arts the world mourns already, and cannot recover. No machine-spun and woven linen equals in fineness the ancient hand-woven linen of Egypt, and no more does the mechanical perfection of the…

[3]

P. 4

…machine-made counterpane equal the charm-ing irregularity of the old “kiver.”

You open the door into the big sunny room and wonder just where to begin to look. A big old wool-wheel is whirring; a small girl is winding bobbins of indigo yarn by the aid of a reel a hundred years old. A little old woman chances today to be teaching some girls to “kyard” smooth, even fluffs of wool. No two of the six modern looms have on them the same pattern of blanket or coverlet. Here is a blanket in stripes of madder, indigo, and white, modelled after one made by a grandmother on Line Fork in her girlhood; there a Double Chariot-Wheel coverlet in blue and white. The heavy pioneer loom holds a rag rug in the making, and across its beams hang treasures woven long ago, shawls, blankets and kivers, Indiana Frame Rose, Tennessee Trouble, Dogwood Blossom, The Cross. A very choice new blue and white coverlet, Snowball and Rose, in summer-and-winter weave, has just been brought in from a neighbor’s loom. Whereas the ordinary overshot coverlet requires four harnesses and four treadles, this weave needs seven harnesses and twelve treadles! But Mrs. Nolan has come to handle it so easily and so pleasurably that she never wants to weave the commoner sort again. It will take her some time to fill the order of the English lady who has just sent for five of this pattern. English visitors always are captivated by our coverlets, because there is today no traditional pattern weaving in England, and nobody can prove that there ever was any, in wool. The extraordinary fact that in no great house, in no cottage or museum, there is a scrap to show that our English forbears wove coverlets, has given rise to one theory that the colonists developed the art here from the designs of hand-woven linen they brought with them.

Besides the six girls who work steadily at weaving and dyeing, a little class of high school girls already proficient in cooking and sewing, has a course in weaving. They learn to design patterns, to thread up a loom, and they weave a cotton dress for themselves with coverlet-pattern bands for trimming. Invariably they delight in this course, and beg to help in the weaving room in payment for their board. Of the two new looms set up in outside homes this year, one belongs to a fifteen-year-old girl from Pine Mountain who wove a coverlet at home in her vacation, even setting up the blue-pot. The money that came from its sale, she used to pay her tuition for this year. The other loom belongs to a vigorous young grandmother. This year, also, a girl who learned weaving and dyeing here and worked at it to earn her schooling, is earning her living in the Fireside Industries Department at Berea.

Even a brand-new, hand-made blanket or coverlet has a mellow beauty upon it, given it by the old hands that have carded and spun the thread, and not been able to extract every burr from the wool; by the anxious care of the girls in the rise of their bloom, watching that treacherous, baffling source of beauty, a blue-pot; by the soft movements of the shuttle carrying the yarn back and forth before the eyes of the weaver who delights in watching the pattern come out on the loom. The accomplishments of any one day often seem insignificant, but when we recently collected our loveliest pieces to send to the Colonial Coverlet Guild of America, (an organization which shares many of our ideals for weaving and dyeing, which was holding a special Pine Mountain meeting in Chicago), the things were so choice and beautiful that we realized what was actually happening in the Fire- side Industries Department. A coverlet is a happy thing to own, still more, a happy thing to make.

[4]

The Marchbanks Press, New York

Previous:

NOTES – 1926

Next:

NOTES – 1928

See Also:

DANCE Guide

FARM AND FARMING Guide

FARM Guide to Sheep, Goats, Weaving, Natural Dyes

WEAVING Guide

Return To:

NOTES Index