Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 09: Biography

Series 17: Students

JOHN H. DEATON Unlicensed Dreamers

TAGS: John Deaton; John H. Deaton; Pine Mountain Settlement School; Harry Robie; harmful settlement schools debate; settlement schools; education; cultural pluralism; cultures; multiculturalism; Jane Bishop Hobgood;

UNLICENSED DREAMERS

In the hard months of winter, we dream of spring and even summer. Though the seasons cannot be ordered up, nor can they be prolonged — we dream and live in any season we choose. We even dream of how the seasons used to march in predictable order while we now nervously wonder at the strangeness of the recent weather. Our dreams can move us through time and space and in an instant tell us who we are and what our deepest fears and desires are. Our dreams hold our fluid souls and free us to roam where we might.

Parker Palmer, the well-known educator, author, and activist has suggested that the best way to capture a glimpse of the soul is to sit quietly and wait and maybe “out of the corner of an eye we will catch a glimpse …”

The many souls of those who passed through Pine Mountian Settlement School have been hinted at in the copious notes, letters, poems, and other ephemera gathered in the school’s archive. In many aspects, the archive is a repository of souls, of UNLICENSED DREAMERS, of those who passed so briefly through Pine Mountain. Today we can only catch a glimpse of those who shared the remarkable educational experiment that was Pine Mountain Settlement. Only so briefly and only fleetingly we capture the essence of a soul whose life touched and was touched by the school or sometimes by us. John Deaton only briefly mingled with the people and the place that was Pine Mountain Settlement School, yet the touching was profound.

There is liberation, spontaneity, and innocence found in many of the archival fragments left behind by those who briefly shared their lives in the remarkable mountain school community of Pine Mountain Settlement. John’s glimpse of the school and our glimpse of John is brief but telling. There are so many souls that are scattered within the Pine Mountain record and nowhere is the glimpse of the soul more elusive than in the paper records and school work of the students. Even when the record is extensive, as it is in the case of John Deaton he only leaves a hint of the person he was and is to become. Deaton, like so many others, eludes even the most astute information gatherers. Maybe it is because the most telling truths about souls are those found in dreams … unlicensed dreams.

Parker Palmer continues

“In our culture, we tend to gather information in ways that do not work very well when the source is the human soul: the soul is not responsive to subpoenas or cross-examinations. At best it will stand in the dock only long enough to plead the Fifth Amendment. At worst it will jump bail and never be heard from again. The soul speaks its truth only under quiet, inviting, and trustworthy conditions.”

Palmer continues with this cultural introspection and notes that if we try to corner that soul, it generally puts up a fight and if we go thrashing about trying to catch it, it rarely puts us closer to the soul of a person, or institution, or even the soul of ideas. Importantly he tells us that the most difficult soul to glimpse is the human soul.

“The soul is like a wild animal — tough, resilient, savvy, self-sufficient, and yet exceedingly shy. If we want to see a wild animal, the last thing we should do is to go crashing through the woods, shouting for the creature to come out. But if we are willing to walk quietly into the woods and sit silently for an hour or two at the base of a tree, the creature we are waiting for may well emerge, and out of the corner of an eye we will catch a glimpse of the precious wildness we seek.”

PARKER PALMER. As quoted in <https://www.brainpickings.org/2014/12/02/parker-palmer-let-your-life-speak/?utm_source=Brain+Pickings&utm_campaign=bf0b02d89f-EMAIL_CAMPAIGN_2017_01_07&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_179ffa2629-bf0b02d89f-236512201>

Just such a glimpse is offered in this poem by student John Deaton

SPRING

The tang of the air, the frosty morning

Spring is here, the buds are swelling

It is just a magic show for those who know

Where to go to see nature’s wonders.

The feeling you have, life is so wonderful

God is good, the earth bountiful

The trees sprout their green leaves quickly

Last year’s leaves look so sickly on the ground.

The sun is bright, the birds are singing

Pleasant noises in my ear are ringing

The teacher’s voice, a pupil’s answer

A stern rebuke, another answer.

I am not a licensed dreamer

To stay all day in clouded splendor

Brought to earth by kind words quickly

Reminded of my assignment gently, to write a poem.

To work I go with high ambitions

Woe is me, another failure

Radiator singing, classmate laughing

Nature beckons and I answer with joy in my heart.

Above the trees and the hills I am soaring

My lofty stand in azure skies.

I look with wondering doubtful eyes

Down upon my foster home.

Recalled again, and not so gently

A classmate’s nudge.

Safe again

In class often my thoughts do wander

My favorite pastime is sound slumber

And do I snore?

— Jack Deaton

In the 1944 Conifer, the School literary publication, Jack Martin, a classmate of Deaton wrote the following story about Pine Mountain Settlement School student John Deaton. In this short piece, we learn not only a bit about Deaton but also something of Jack Martin.

DEATON’S DILEMMA

John H. Deaton, head man of the paint crew, trudged wearily into the shop one morning after spending half of the night fighting fire on Gabe’s Branch. Just as he was about to drape his exhausted body over a chair, Mr. [Glenn] LaRue informed him that he was to continue with the painting of the school house. John stood petrified with astonishment, his visions of spending an easy work period in the shop blasted to nothing. He was, however, too tired to differ vocally with Mr. LaRue; so the boys got their paraphernalia into readiness.

As usual William Tye had lumbago, backache, or some other ailment which made him, so he thought, physically unable to carry a ladder to the schoolhouse from the shop. He finally agreed to carry it on the condition that he would not use it, as he is allergic to high altitude.

Upon arriving on the scene of operations, his fellow painters, as usual, flattered William about his being such an accomplished wielder of horsehairs. In consequence, fifteen minutes later when Mr. LaRue came around to see how things were going, he found George William at the top of the ladder, painting under the eaves and lustily singing Incognito Serenader. This was very appropriate because William was unrecognizable under a coat of paint.

All the while Mr. Deaton had not been unoccupied. While his brush, perhaps, had not been as vigorously wielded as usual, he had not done so badly after fighting fire the night before. And when the quit work bell had rung and he had carefully shepherded his flock of painters back to the shop and had gotten them cleaned up, William, having had to wash his hair in turpentine, he felt very well satisfied with himself as he went home to prepare for a full day of school work. — Jack Martin

In that same issue of the Conifer, John Deaton wrote the following poem

DESPAIR

In his face was written a story of hardship.

Lines were etched deep by the unkind years—

Seventy-one of them.

His fingers were cracked from working bare-handed;

His eyes were pools of misery,

As he walked slowly down the road

Like a man in a fog—

Or a dream.

His had been the life of the pick and shovel,

Of long days of work and short nights of rest,

Of grimy coal-dust and the roar of motors.

He had felt the bitter pangs of hunger,

And had seen his children forced to leave school

For lack of clothing.

He had been young once, able to do a hard day’s work

Without feeling it, but now his shoulders ached

And his back hurt.

Ragged and dirty, he no longer had the strength

To battle his poverty or even to care how he looked.

In his hand was an order for his time,

Signed by the foreman. Fired!

Bitter and silent he stumbled onward.

— John Deaton

This poem won Honorable Mention in the National High School Poetry Contest and was published in the Annual Anthology of High School Poetry, 1944.

John Deaton was passionate about Appalachia. He knew its dark corners as well as those filled with sunlight and fresh air. He never forgot where he came from and never lost sight of where he was going. In all the years of being and becoming he was filled with a passion for Pine Mountain Settlement School and frequently came back to the School to visit and to later serve on the Advisory Board of Trustees.

He was always a champion of hard work and high dreams but his school career did not start out that way. Glimpses of the soul of John Deaton and his years at Pine Mountain may be found in the passionate response, “My Settlement School,” that Deaton penned in response to an article by Harry Robie, a faculty member at Berea College. Robie proposed in his provocative thesis “…That on Balance the Settlement Schools Were Harmful to the Culture of the Southern Mountains.” Deaton strongly objected.

JOHN H. DEATON’S Response to Harry Robie’s “Resolved: That on Balance the Settlement Schools Were Harmful to the Culture of the Southern Mountains.”

GALLERY – Response to Harry Robie’s “Resolved: That on Balance the Settlement Schools Were Harmful to the Culture of the Southern Mountains.” MY SETTLEMENT SCHOOL

- deaton_john_001

- deaton_john_002

- deaton_john_003

- deaton_john_004

- deaton_john_005

TRANSCRIPTION

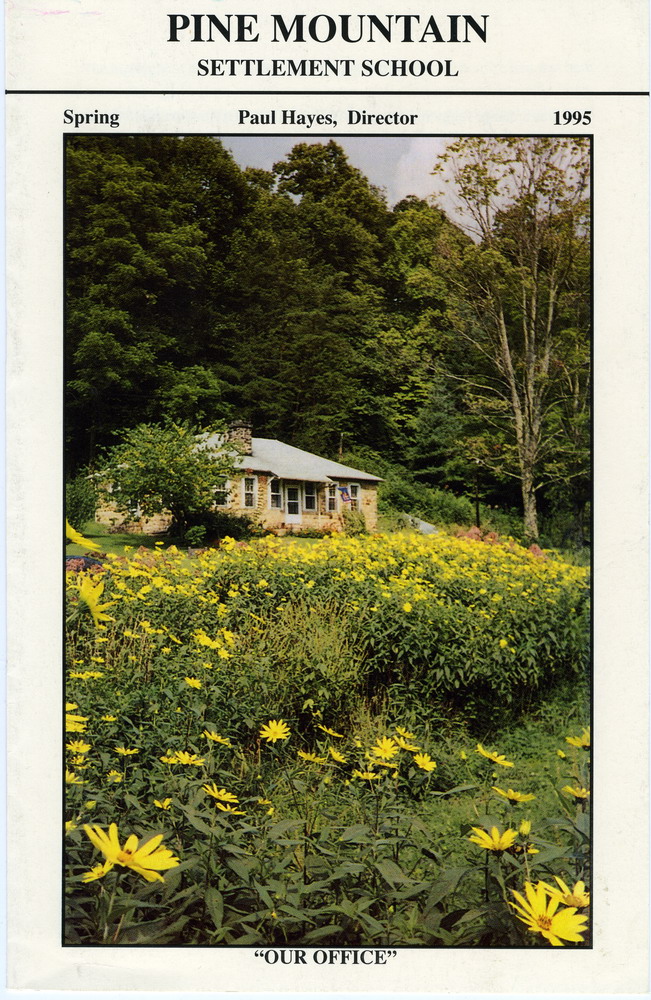

NOTES – 1995 Spring, page 1. [PMSS_notes_1995_spring_0011.jpg]

MY SETTLEMENT SCHOOL

By John Deaton

Harry’s fallacious indictment of settlement schools must not be allowed to go unchallenged. It would be impossible for even a knowledgeable scholar to attribute identical goals and objectives to such a diverse group of institutions and evaluate the results collectively in an objective manner His effort is a regurgitation of sterile gleanings from dubious sources. The Pine Mountain Story 19131980 by Mary Rogers is a source he should not have overlooked. I drew on it freely for the facts I offer in rebuttal. If Mr. Robie’s logic was used to make stew, the meat vegetables and seasoning would be omitted leaving the cook with nothing but hot water. It’s too bad that apparently he neither visited a settlement school nor talked to anyone who either attended or worked at one.

I accept the fact that my settlement school changed my cultural concepts and exposed me to new and exciting things such as indoor plumbing central heat and electricity. I have no doubt that my experiences parallel those of many of my classmates who were also refugees from the coal camps of southeastern Kentucky. I do not accept Mr. Robie’s claim that my cultural heritage was harmed. Obviously, he has never spent a wintery morning hugging a coal stove and dreading a trip to a friendly but frigid outhouse. Doing homework by a smoky coal oil lamp was not all that much of a thrill either.

p.2

During its seventy-seven years of service to the residents of both contiguous and “fur off” areas, Pine Mountain Settlement School has remained true to the charge of its founder, William Creech. He said, “I don t want hit to be a benefit just for my grandchildren and the neighbors, but for the whole county, and the state, and the nation — and the people acrost the Sea too, if they can get any benefit out of hit.” He deeded his land to be used for school purposes as long hit.” … as the Constitution of the United States stands.

From its beginning, Pine Mountain Settlement School attracted an impressive cohort of dreamers and doers. That tradition began in 1913 with Katherine Pettit and Uncle William Creech and there is evidence that it is very much alive today. Adults, as well as children, were and are central to the school’s interests and concerns. Throughout the history of the institution, there was no attempt to substitute an alien culture for that which was present as many scholars have suggested.

There was, instead, an exchange of the best of human cultures shared through example. For example, the school encouraged better farming methods and stock management. Local community adults taught both the students and the teachers how to spin, dye and weave. The students were taught personal hygiene and manners. They, in turn, introduced their teachers to ballads and singing games. The cultural exchange that formed the existing cultural milieu encouraged and abetted, not harmed. Four separate and distinct core programs were developed in anticipation of and in response to changing needs. They can be identified as: The Early Years: 1913-1930. The Boarding High

p.3

School: 1930-1949, The Community School: 1949-1972,

Environmental Education: 1972—to present.

The school opened in 1913 using borrowed buildings and tents while permanent facilities were being built. It was not unusual for the modest tuition to be paid in kind or by labor. There was a continuous effort to find room for “just one more. ” The initial health program was expanded to include a doctor and an infirmary and for decades, Pine Mountain Settlement School provided the only source of medical service for an area of three hundred square miles.

The boarding high school years saw the addition of a full-time guidance counselor to the staff in 1935. In The Pine Mountain Story 1913—1980, Rogers describes the impact of this effort on the Harlan County School System. “One of the most promising undertakings during these years was the effort to help Harlan County set up a county-wide guidance program. Pine Mountain School had carried on a counseling program for several years and was constantly studying new

approaches. Now that the population was stable, it was possible to concentrate on the quality of education in the schools. The County Superintendent welcomed Mr. Morris’s [Glyn Morris, Director] suggestion that a “Guidance Institute” be held annually on the Pine Mountain campus. Aided by specialists from the Alliance for Guidance Of Rural Youth, three such Institutes were held. The outbreak of the War put a stop to this promising beginning,

p.4

which had attracted nationwide attention in educational circles.

During the community school period which was triggered by the need to consolidate several one-room schools, Pine Mountain Settlement School, in cooperation with the county system, met this new need. Pine Mountain provided classrooms, playgrounds, a dining room and an atmosphere that was conducive to learning. The school assisted in the recruitment of qualified teachers and provided housing for them. Competent supervision and leadership was present in the person of the resident Director. The County paid the salaries, classroom rental to offset the cost of maintenance and other related expenses. When the first-grade teacher recognized that many students were totally unprepared for school she [Mildred Mahoney] organized a “Little School” for the Summer months of 1963. She later Shared her experience and offered assistance in training teachers in Title I and Head Start.

The current and ongoing program to identify and assist potential dropouts has been adopted as a model for the state of Kentucky.

Each period in the life of the school has brought new challenges and each challenge has been met. The willingness of Pine Mountain Settlement School to share completely the lessons it has learned with others is a measure of its commitment to the

p.5

philosophy of its founder [he refers to Uncle William Creech].

My personal involvement with Pine Mountain Settlement School began in the fall of 1940 when I showed up on the campus as a not quite fourteen-year-old sophomore. I was not exactly a model student and I suspect that I had a champion on the staff who must have worked overtime. I left Pine Mountain three times, twice for a period of a week or so and once for a year. Something always drew me back. The understanding and the love that was given me is vivid in my memory. The learning experiences that I encountered in the dormitory, in the dining room, on the job, and in the classroom were unusual and effective. I still remember the pride I felt when I was chosen to be on the milk crew because that meant that I was considered to be responsible. Numerous teachers led me gently but firmly into new worlds. Brit Wilder, by both words and example, taught me that there is dignity in honest labor and that alone was worth the price of admission which I paid by working on the farm during the summer.

Both Mr. Roble and Thomas Wolfe are wrong. You can go home again and this year, on the second Saturday in August, I’ll do just that. I make no attempt to speak for my countless brothers and sisters, but for a few magic hours, at our annual Pine Mountain reunion, I’ll be both home and seventeen again.

See Also:

JOHN H. DEATON (Biography)

JANE BISHOP HOBGOOD Response to Harry Robie

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH Robie Harmful Settlement Schools Debate