Pine Mountain Settlement School Series 09: BIOGRAPHY Staff Alice Cobb “War’s Unconquered Children Speak” 1953

Alice Cobb. [cobb_alice_018.jpg]

TAGS: Alice Cobb, War’s Unconquered Children Speak, Pine Mountain Settlement School, Sophia L. Fahs, Mary Catharine Nelson, children, war, international conflict, social services, WWII, race relations, Mid-Century White House Conference for Children and Youth, Youth Guidance Institute, Glyn Morris, Ruth Strang, O. Latham Hatcher, Alliance for Rural Youth

ALICE COBB “War’s Unconquered Children Speak”

A copy of a “long-lost” early book by Alice Cobb has recently been found by Mary Catharine Nelson, the owner of Ideas into Books® Westview. The book, War’s Unconquered Children Speak, originally published in 1953, is a timely find and has as much to tell us today as it did when first published.

ALICE COBB: Pine Mountain and Beyond

Alice Cobb, the author, worked for many years at Pine Mountain Settlement School and is one of the School’s most skilled and insightful writers. In the 1950s, following her work at Pine Mountain Settlement School, Alice Cobb worked at an urban settlement house in the slums of Brooklyn and following that, she served as a consultant for the Kentucky Division of Child Welfare as their go-to person for State Community Organization. While in that position her writing skills were again called into action. She helped to write the Kentucky report for the 1950 Mid-Century White House Conference for Children and Youth.

The 1950 Mid-Century White House Conference was part of a long-running series of conferences first established by Theodore Roosevelt and continued by succeeding Presidents. The 1950 Mid-Century Conference was particularly important and helped to begin a change of course for children’s education in the 1950s, one that brought attention to the guidance and mental health of students in public schools. Cobb was very familiar with this Progressive educational reform agenda, as she had worked at Pine Mountain Settlement with Director Glyn Morris whose educational Youth Guidance program at the School was one of the most unique and experimental progressive educational programs in Kentucky.

Glyn Morris and his successors were an important influence on Cobb and no doubt strengthened her commitment to the welfare of children. Glyn Morris began his Youth Guidance Institute at Pine Mountain just a few short years following his arrival in 1932. Strongly influenced by the educational objectives of John Dewey, Morris built a program that received national attention. Many of his ideas and those of Dewey may be seen in the 1950 Mid-Century White House Conference for Children and Youth. But Morris was not alone, even before his initiatives the attention of the Nation was turning toward the growing problems of the war in Europe. By 1940 a Committee for the Care of European Children (CCEC) was established with Eleanor Roosevelt as honorary president. Roosevelt and the acting President of the Committee,

Marshall Field, argued for the admission of as many children as could be managed into the United States as refugees. It was anticipated that some 20,000 foreign children could benefit from their extended programs. With this attention to the war refugees came the efforts of the Mid-Century White House Conference that focused its attention on the children in America. In the Mid-Century Conference, the lens shifted to the rural areas of the country, to minorities, to children of the inner cities, and to all low-income families, as well as children with disabilities. But the primary focus was on the emotional well-being of children. The conferees aimed for the development of a “healthy personality” in all children. Discussions regarding racial discrimination dominated many committees. The Conference had a large agenda but by 1953 the Federal Security Agency had become the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

With a renewed interest in the mental health and “healthy personality” of children, Alice Cobb struck out for Europe and the Middle East in 1953, just shortly after the national ground-breaking conference for children and youth. Cobb’s journey was financed and supported by over thirty agencies, church boards, and organizations, as well as by a number of individuals, Cobb visited nine countries in Europe and the Middle East. According to author Sophia L. Fahs, who wrote the introduction to War’s Unconquered Children Speak, Cobb “…wished to see and understand the problems of the displaced people of the world through their own eyes and feelings.”

War’s Unconquered Children Speak

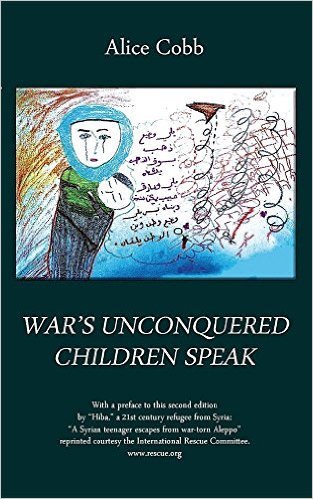

The cover of the newly published and revised edition of Cobb’s book goes one step further and graphically ties the journey of Cobb to children’s contemporary issues in both the Middle East and in Europe. Today, as during the post-war period of the 1950s, children are the focus of concern to many international agencies. Nationally the Mid-Century White House Youth Guidance Conference of 1950, and the innovative Pine Mountain Settlement School programs of the 1930s and 1940s, and the work of Glyn Morris’ Youth Guidance Institute, were prescient in their educational reform and the need to integrate education with a guidance and a “healthy personality.” The work of Cobb and so many others paved the way for many children to move toward success. The needs of rural children whose lives were and are threatened by poverty, war, or abuse joined those children from the distressed urban environments to call attention to the international crises that has never gone away. Hiba (a pseudonym) is a Syrian refugee from Aleppo who describes her drawing on the cover as

“… a mother who is trying to protect her child, but can’t. I didn’t draw a house; I drew safety in a mother’s arms. Next to it, I wrote a little poem about Syria. It reads: ‘A person who lost his gold can find it in the gold market, and a person who lost a lover will soon forget him, but a person who lost his country, where will he find it?'”

Cover drawing by Syrian refugee, Hiba (pseudonym). Used by permission of the International Rescue Committee (IRC). [51AS-jGLbL._SX311_BO1204203200_.jpg]

Hiba is one of many Aleppo refugees from today’s conflicts in Syria. Her story and drawings integrate well with Cobb’s interviews of 1953. Both accounts carry the seeds of what is now driving international movements to new energy to aid displaced and traumatized children, no matter their city, state, or country of origin. While the 1950 Mid-Century White House Youth Guidance Conference was particularly important in focusing in on the psychological side of children and youth and the concerns raised by war and now terrorism, it also acknowledged for the first time that children and youth need to speak for themselves. Approximately 400 children were in attendance at the 1950 conference, including a small group from Kentucky. A declaration of the rights of children was one of the most important documents to come from the conference. It advocated for “an ecological and strength-based approach to improving [the] health and well-being” of all children.

ALICE COBB and Glyn Morris

The early work of Glyn Morris with the talented educator O. Latham Hatcher and the engagement of Pine Mountain with such programs as the Southern Women’s Educational Alliance, and later the Alliance for Guidance of Rural Youth, kept Morris and those who worked with him in a unique and progressive educational circle working for children during the time Cobb was writing her first book. If he played a direct role is not known. Director Glyn Morris left Pine Mountain in 1941 to join the war effort and was stationed in Europe as a war chaplain. His position at Pine Mountain was not held for him as the war was expected to persist for years. At war’s end he returned to work in Harlan County, however, as a school principal at Evarts, Kentucky. Following Evarts, Morris went to Columbia University to work with Dr. Ruth Strang for his doctorate in education. Cobb continued her relationship with Morris and with Pine Mountain through correspondence and through occasional visits with her close friend Mary Rogers, during this time.

ALICE COBB post-WWII

When Cobb received a stipend to travel to the Middle East and Europe for four months in the early 1950s she was well prepared to listen. When she gathered her interviews for War’s Unconquered Children Speak she had also been well sensitized. When she returned home the United States was only in its seventh year of recovery from WWII (end, Sept. 2, 1945). The wounds, both physical and mental, were still raw.

While the wounds to Europe and the Middle East went far deeper than those experienced by any American city, the scars of war were still evident in soldiers and their caretakers in the U.S.. In Europe and the Middle East cities and homes were in ruins and many family lives were shattered by war The scars both psychological and physical, were often deep. Many children whose lives touched the war in a variety of ways, were still healing and still mourning.

At home in the 1950s, the United States was in war recovery mode, but unlike Europe, the recovery was characterized by an economic boom. Suburbs grew where farms used to sprawl. Factories and assembly lines were in full operation. Employment was robust. In post-war Appalachia, coal mining was still producing work and the population of Harlan County, Kentucky, was over 80,000 including some 650 foreign-born and 7500 African Americans. From an economic perspective, economic life was generally good. Yet, in Harlan County in 1953, sixteen men lost their lives in the mines and the year before, seventeen men died. Even more disturbing was the labor strife which continued as miners fought to build safe and fair working environments for themselves and send their children to good schools. While employment was good, wages were low and lifestyles began to degrade. The youth in Harlan County were beginning to be restless and school discipline and crime were on the increase.

In America in the 1950s, and even now in the 2000s, millions have not been displaced by war nor have they experienced the ravages of war. No towns were reduced to rubble. Families were not forced into migration with the exception of mining booms and busts. Many children were growing up without their soldier fathers, but families remained largely intact. Overall, the post-war period was characterized as the “dull ’50s”. It was not an uncommon characterization of the times particularly in the urban and suburban areas of America. It was and is a life that signals complacency and that complacency still lurks in many corners of the country. But, beneath this “dull” exterior were signs of unhealthy life practices, and children whose mental health was in question.

However, Alice Cobb, very much a woman of the world, did not see the era as “dull” and she would not be complacent. While at Pine Mountain she was the appointed promotion and publicity outreach person for the School and she tested the landscape of both rural and urban post-war revitalization. [See ALICE COBB for a full biography.] Known for her sharp observation and her assertive advocacy for the School and for the Appalachian community that struggled in the post-war years and beyond, she was finely tuned to rural life and urban life and to both the national and the international pulse. Always an advocate for children, her project to document world conflict through their eyes was a project that she had long held close to her heart and wanted to share. It was a central dialog she returned to throughout her life.

ALICE COBB “The Story of Kathy”

It was a terrible disappointment when in 1950 she presented her manuscript from her European and Middle-East journey to Beacon Press and they only published a limited run of War’s Unconquered Children Speak. It failed to capture a large readership. Apparently many in the world wanted to move on to forgetting, not remembering — to complacency. Later in her life, she spoke to her friend, publisher Mary Catharine Nelson, many times about her first full-length book that she believed was her “best thing.” Further, she, amazingly, had no remaining copy of this work, nor was either Alice or Mary Catharine able to locate a copy before Alice’s death. Her friend Mary Catharine notes in her Dedication (included in the new edition), that Cobb “grieved its [the book’s] loss as one might grieve a stillborn child.”

It was not until 2016 that a copy of the 1953 Beacon Press publication was located and with it came the discovery that the copyright had not been renewed and the book was available for re-issue. Mary Catherine, with joy, was able to posthumously address Alice in her dedication to the 2016 edition and said, “And so, dear Alice, I dedicate this second edition to you. Here is your ‘best thing.’ Sorry it took so long.” Alice Cobb continued to publish for the remainder of her life.

Her books, articles, and scholarly works promote her interest and her dedication to giving voice to the many voiceless, neglected, and abused in the world, particularly its children. She would always remain sensitive to children and race relations, two themes that permeate her work. For example, the themes strongly come forward in one interview in War’s Unconquered Children Speak. The interview with “Kathy” a German girl in Giessen, is a powerful record of the external and internal conflicts that war often inflicts on children and families.

Kathy, who became a social worker following the war, captures in her narrative the many conflicting values that often occur in the war’s aftermath. In both Kassel and Giessen, Germany, the occupation of American troops gave rise to numerous “brown babies.” the mixed-race children of German women and African-American soldiers. Kathy provides a raw picture of the pressures of race relations that often follow occupation and conflict. Kathy, who became a social worker following the war, captures in her narrative the many conflicting values that often occur following wartime experiences.

BROWN BABIES

In both Kassel and Giessen, Germany, the occupation of American troops gave rise to numerous “brown babies.” the mixed-race children of German women and African-American soldiers. Kathy provides a raw picture of the pressures of race relations that often follow occupation and conflict. Cobb and Kathy tell the story of one European town’s integration challenges around the bi-racial children and the pressures placed on their families as a result of the occupation. Many of the “brown babies” born out of wedlock felt the full force of discrimination from the town and abandonment by their American fathers. Kathy describes the local practice in which bi-racial babies and young children were often abandoned, killed, or abused by their parents or families and the scars that these abuses left on the children. Cobb’s description of Kathy, who became a German social worker following her own childhood war-time crises, describes with some trepidation her homeland as only beginning to come to terms with race relations as a facet of war’s aftermath.The interview captures the ambivalence of Kathy toward the occupiers but her over-arching sense of humanity and need to reach out to children is strong.

Cobb’s interviews are both sensitive and prescient. Today’s accounts of similar events often carry echoes of these early assimilation struggles in war-torn areas but the audience has become less sensitive. “The Story of Kathy,” the German social worker’s interview, like so many other interviews in the book, speaks to universal behaviors in times of war and in times of peace. Though written in 1952-53, Cobb’s book signals hope. Today, Germany has become one of the most welcoming countries in Europe for immigrants and people of color as many European and Middle-Eastern cities, towns, and rural populations grapple with mass migration, racism, violence, displacement, and psychological trauma. Cobb’s book helps us all to move our listening and our dialogue forward.

War’s Unconquered Children Speak CHAPTERS AND INTERVIEWS

A listing of the chapters and interviews of War’s Unconquered Children Speak provides a good grasp of the book’s scope.

FROM GREECE

This Little Piece of Earth I, Sophia Alexiou Democracy With a Greek Look Easter in Lamia

FROM THE MIDDLE EAST

The Arabs and the Jews Round About Damascus How Many Miles to Bethlehem? Amirah Mustafa Spring in Gaza Israel: Modern Drama in an Ancient Setting Ben Shemen Boy Vicente From Venezuela

FROM ITALY

Born to Sing A Palace in Naples The Story of Casa Materna “Life is O.K.”

FROM FRANCE

Exiles From Spain Children of the Pyrenees

FROM GERMANY

The German Problem Half-and-Half: the “Brown Babies” The Story of Kathy My Dear Tatjana When Giedra Speaks Again

FROM FINLAND

Green Gold Posti Auto to Imari Lastenkoti in Lapland Very Simple — Very Practical

APPENDIX

A copy of the book may be purchased through the following source: (AMAZON)

See Also: ALICE COBB Guide to Writings, Collected Stories

ALICE COBB Staff Trustee Biography

ALICE COBB Correspondence 1940s

Image and transcription of contract between Cobb and PMSS for publicity work in 1941-1942.

FARM 1935 Community Fair Day

as described by Alice Cobb, September 23, 1935

GLYN MORRIS Correspondence 1976 Letter to Alice Cobb

ALICE COBB Travelogue 1941 ALICE COBB Travelogue 1942 ALICE COBB Travelogue 1946