Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 10: BUILT ENVIRONMENT

Indian Cliff Dwelling

Discovered May 1923

TAGS: Indian cliff dwellings, rockshelters, Archaic Native Americans, excavations, cliff overhangs, burial sites, epidemics, archaeology, anthropology, artifacts, Dr. William D. Funkhouser, Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), funeral songs, re-burials, Pisgah phase, maize agriculture, Kentucky Mississippian period, Environmental Education collection

INDIAN Cliff Dwelling, Discovered May 1923

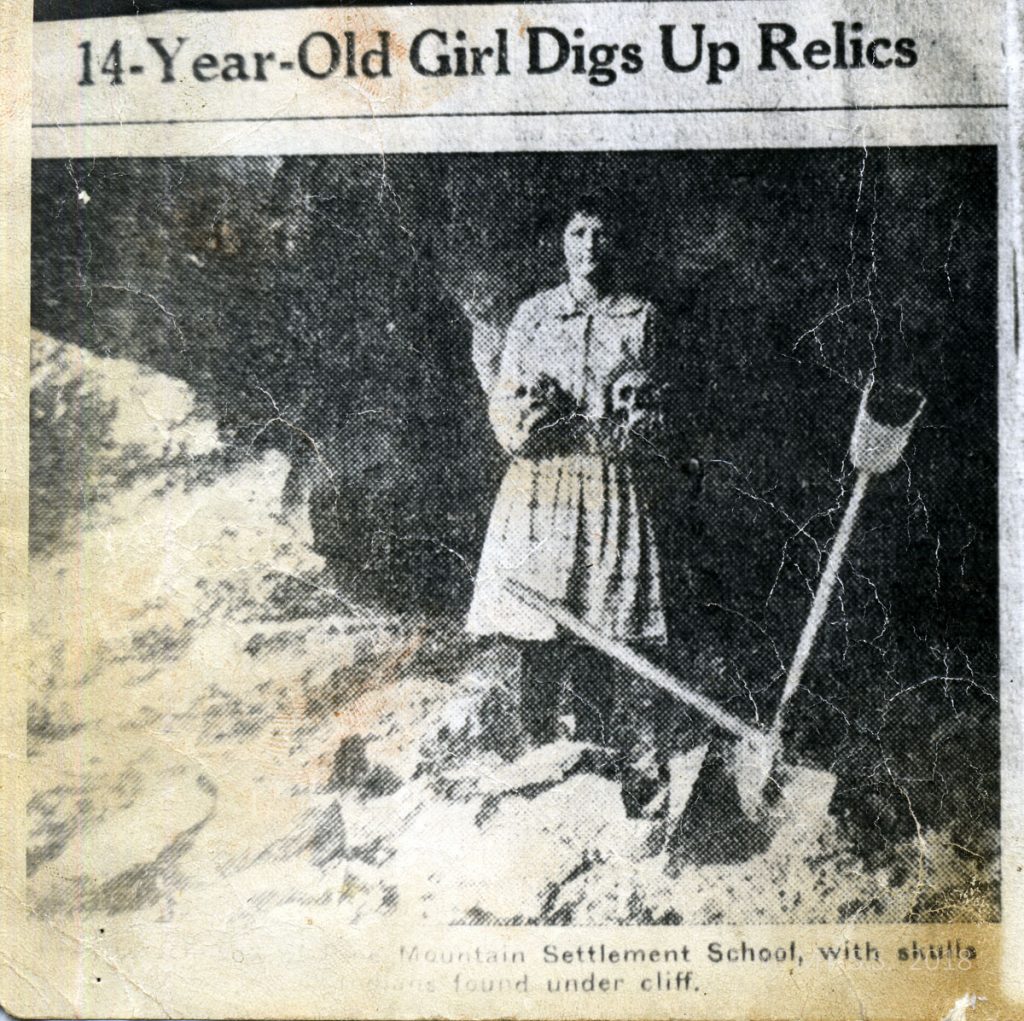

The Indian Cliff Dwelling (rockshelter) is an ancient Native American site discovered in 1923 by a student when she was part of a group of students exploring a cliff over-hang near the entrance to Pine Mountain Settlement School. The site was used as an early dwelling but archaeological evidence indicates that the site was also repeatedly used as a burial site. The more recent of the burials contained numerous skeletons, suggesting that an epidemic disease caused a rapid and large death event. A comprehensive excavation of the site was conducted by the University of Kentucky shortly after its discovery and it is this archaeological study that provides the most authoritative information on the cliff site.

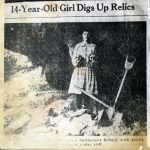

When the site was found in 1923 it was not the innocent discovery of uninformed children. One of the group, Frances Johnson, had brought a mattock to the cliff declaring, “I’ve brung a mattock; I aim to dig me up an Indian!” She had obviously been familiar with other cliff burials and had participated in the digging for Indian artifacts. She quickly unearthed a skull and bones and with the help of her classmates, several more skulls, and bones followed.

PMSS files. Lexington Herald, May 6, 1923. Caption: “Frances Johnson, of Pine Mountain Settlement School, with skulls of Indians found under cliff.” [indian_cliff_dig.jpg]

Unearthing Indian remains was a common occurrence for many years in eastern Kentucky, which once supported a large Archaic Native American population. Many of the sites possibly date back to early Archaic time. A large number of cliff “overhangs” may be found throughout the area, but most have been ravaged and many have recently been buried by surface mining operations. Cliff overhangs were also temporary homes for explorers, for settlers and hunters, and later for livestock shelters. Initials and sometimes dates carved into the stone suggests these natural shelters served many purposes and occupants over the course of many years.

Native American inhabitants did not often stay in one location for long periods of time in the early Archaic period, but they may have been continual seasonal occupants at the Pine Mountain site. The Late Archaic period apparently had more nucleated (family) groups and many of these were continual occupants of selected sites that were particularly hospitable, as was the large south-facing cliff near the clear stream of Isaac’s Run. The bottom-land near the cliff could easily support crops of corn and squash and the mountains had game to provide for a very abundant food store. When the nearby fields were plowed following the development of the School, they quickly yielded considerable flint and arrowheads. Occasional axes, shells, and gorgets were also found suggesting the site had both a long history, perhaps had links with more dense populations.

To read more news reporting regarding the Native American discoveries at Pine Mountain, see INDIAN CLIFF “Ancient Relics Discovered by Mountain Girl,” which provides images and transcription of the Lexington Herald article of May 6, 1923. Prepared by a contemporary writer concerning the finding of the gravesite, it provides additional details.

INDIAN CLIFF DWELLING: University of Kentucky Excavators

In 1923 there were no laws to protect these early Native American sites, only the good conscience and historical sense of the staff at the School who quickly put a stop to the plunder by the students. Staff members protected the graves and the archaeological history of the site and expert help was summoned to the School from the University of Kentucky. Dr. William D. Funkhouser, a zoologist, and Dr. Arthur McQuiston Miller, a geologist, and Victor K. Dodge (called Major Dodge in the reports), all members of a group of scholars interested in early Native American rockshelters, arrived just after the discovery and took charge of a controlled excavation of the site.

While there was “expert help,” on site, the group had not yet been recognized as archaeologists or anthropologists. Under the guidance of physicist William S. Webb, Funkhouser and his colleagues shaped the first department of anthropology and archaeology at the University of Kentucky, gaining departmental status in 1926, three years after the excavation. The University of Kentucky department was the second department of anthropology to be created in the Midwest. (Griffin. 1975:5 as cited in Lewis 1996:10).

Funkhouser described his work at Pine Mountain in a short summary found in the important work, Ancient Life in Kentucky: A Brief Presentation of the Paleontological Succession in Kentucky Coupled with a Systematic Outline of the Archaeology of the Commonwealth, co-edited with William S. Webb in 1928 and considered a seminal work on Kentucky archaeology. He describes the Harlan County site as

Rockhouse at Pine Mountain Settlement School. An overhanging rock shelter not more than twenty-five feet deep. On Greasy Creek, a tributary of the Middle Fork of the Kentucky River where it heads up against Pine Mountain. Region is rich in flint artifacts. Slope to creek apparently a workshop for flint-makers. Four complete skeletons, one with a greatly deformed skull. Many artifacts and a few animal bones with the skeletons. Examined by A.M. Miller, Victor Dodge and W.D. Funkhouser.

While in the Pine Mountain area, Professor Miller examined a number of rockhouses nearby in order to “determine what they might offer in the way of fields for archaeological investigation.” The unidentified news report of the work of the three university professors also notes that Miller also looked at what he described as a “cave sink in the MIssissippian limestone, where it had been pushed up by faulting so as to form a steep bluff on the western face of Pine Mountain about three miles southwest of the school.”

The excavation of the rockshelter at Pine Mountain was at the very beginning of the extensive scientific work conducted by the University of Kentucky and by universities in surrounding states. However, it was many years before the science got a conscience and before the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was instituted by the Federal government.

INDIAN CLIFF DWELLING: Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA)

Today, the practice of “digging up Indians” is illegal. It violates the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), Pub. L. 101-601, 25 U.S.C. 3001 et seq., 104 Stat. 3048, a United States federal law enacted on 16 November 1990. Today, current law is very specific regarding the repatriation of remains and artifacts.

On October 29, 2013, the new NAGPRA regulation section 10.7, “Disposition of Unclaimed Human Remains and other Cultural Items Discovered on Federal Lands After November 16, 1990,” was published as a proposed rule. Read the text of the rule here.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act was enacted on November 16, 1990, to address the rights of lineal descendants, Indian tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations to Native American cultural items, including human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony. The Act assigned implementation responsibilities to the Secretary of the Interior. Staff support is provided by the National NAGPRA Program, including:

- Publishing notices for museums and Federal agencies in the Federal Register,

- Creating and maintaining databases, including the Culturally Unidentifiable Human Remains Inventories (CUI) Database,

- Making grants to assist museums, Indian tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations in fulfilling NAGPRA,

- Assessing civil penalties on museums that fail to comply with provisions of the Act,

- Providing staff support to the NAGPRA Review Committee and for the Annual Report to Congress,

- Providing technical assistance to Federal agencies where there are excavations and discoveries of cultural items on Federal and Indian lands,

- Promulgating implementing regulations, and

- Providing technical assistance through training, website information, reports prepared for the Review Committee, supporting law enforcement investigations and direct personal service.

According to the definition of NAGPRA on Wikipedia :

NAGPRA … establishes procedures for the inadvertent discovery or planned excavation of Native American cultural items on federal or tribal lands. While these provisions do not apply to discoveries or excavations on private or state lands, the collection provisions of the Act may apply to Native American cultural items if they come under the control of an institution that receives federal funding. [http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Native_American_Graves_Protection_and_Repatriation_Act, accessed January 11, 2014.]

The current provisions are also not bound by the date of the legislation and include removals that occurred prior to the enactment of the 1990 NAGPRA laws.

A description of the excavation is found in the Pine Mountain Notes of November 1926:

The mattock and the hoe then gave place to the kitchen fork, the toothbrush, and the sifter in the hands of a gentleman with infinite patience …” The work of the on-site team from the university was followed by analyses by zoologists and geologists. The latter helped to locate fire-pits, middens, and other typical site markers that provided clues to living patterns, diet, and family or tribe size and age of the cliff dwellers.

INDIAN CLIFF DWELLING: Re-Burial

The result of the university’s careful excavation yielded, in total, nine skeletons (four intact), all buried in a “sitting posture, some with the bones of the turkey wings that had been placed beside them for their last journey …” [PMSS Notes, Nov. 1926] One of the skeletons was wired together and removed to the University of Kentucky for further study. Other bones were added to the biology collections of the School and the remaining were re-buried “…where they had lain so many hundred years.”

Strangely or not, the re-burial following the excavation was accompanied by the singing of an old-time mountain funeral song:

Been a long time travelin’ here below,

Been a long time travelin’ away from my home,

Been a long time travelin’ here below,

To lay this body down.

The choice of this song for the re-burial ceremony may seem peculiar to the present day, but at the time it signaled the deep respect most mountain folk have for the burial process, or “funeralizing,” as they call it. This traditional mountain practice helped to assuage the distress shown by some students and community at the disturbance of the graves and the removal of the human remains for study. For many in the valley, these were their ancestors. The 1926 Notes account describes the community response to the discovery:

It is to be said that many of our pupils and neighbors got no thrill out of this discovery, but wanted the dead left in peace, and were truly horrified at their first acquaintance with the Howard Carters of this world.* [*A reference to the well-publicized discovery by the English archaeologist, Howard Carter, and Lord Carnarvon, of King Tutankhamen’s Tomb in Egypt in November of 1922, not many years before the Pine Mountain discoveries at the Indian Cliff dwelling. ]

The cliff skeletons and artifacts are further described in the 1926 Notes:

Two of the skulls were of a very early type. There was one of an old man who had trouble with his teeth. A tiny baby’s skull, whose milk teeth had never cut through the jaw, showed that the cliff was at times more than a hunter’s or warrior’s lodge. There were at least two layers of graves, so it seems that for several hundred years, perhaps only at intervals, the Indians lived there.

Most likely the Indians died from European diseases that decimated many tribes after the arrival of Europeans. It was evident from the archaeological exploration that the Native American families living in the valley experienced a catastrophic event that killed many of them. The pattern was consistent throughout the Americas when Europeans arrived. Burial beneath the cliff, which was once served as an active settlement, was not unusual. It was also not unusual to find later occupants living on top of grave sites, complicating the archaeological history of these mountain cliff dwellings.

INDIAN CLIFF DWELLING: Farming in the Pisgah Phase

The Native American families living on the banks of Isaac’s Creek were probably farming communities in their later phase. This later period is called the Pisgah phase and was common in Harlan, Letcher, and Perry counties (Niquette and Henderson 1984:54). The Pisgah phase spans most of the Kentucky Mississippian period in the southern Appalachians (Lewis 1996:151). As Barry Lewis also notes in his book, Kentucky Archaeology, the phase was commonly found but “only a few Kentucky components have been identified [for this period].” The fertile bottom-land along the north flank of the Pine Mountain was a protected and pleasant location and the Indians left traces in flint and stone of their numbers and their hunting and agricultural activity. The flint and stone traces were greater in this Pine Mountain location than in some other areas due to the possible importance of the site as a flint manufacturing site.

Though small and narrow, the bottom-land along Greasy Creek and Isaac’s Run could have supported grain crops such as maize. However, it is well-known that many Indians cleared and cultivated various crops up the steep slopes of the mountain. Their early farming was foundational to the later practice of the pioneer families who adopted some of the practices and whose farming practice is often described as “subsistence farming.”

It is maize agriculture that marks the “fundamental cultural changes associated with the Mississippian tradition,” writes Barry Lewis. This would possibly place the population in the Pine Mountain valley around A.D. 900. There does not appear to be a significant decline in the population of the area until the Europeans or their diseases had made progress into the interior of the country, around the late 1500s, into the 1600s. The recent publication of Charles C. Mann’s book, 1491, raises the question of the impact of disease in the New World and the resulting debate regarding the decimation of Native populations in the New World, has still not settled down. But, the population of Native Americans in the southeastern counties of Kentucky appears to be large and their number appears to be substantially above earlier calculations.

Ben Begley With Native Americans collection display, March 2005. Begley was former director of the PMSS Environmental Education program 1986-2014. [pmss_photo_begley_cropDB.jpg]

INDIAN CLIFF DWELLING: Environmental Education Collection

The Environmental Education program has gathered a rich collection of artifacts from the area’s Native Americans. The collections were donated by staff workers, Fred Burkhard, William Hayes, and James L. Faulkner who all gathered flints, stone implements, and pottery shards from the fields of the School as the farmland was tilled in the 1930s through the 1950s. These implements and flints comprise the bulk of the Native American educational collection at Pine Mountain.

The collection has been inventoried and largely contains flint implements, arrowheads, some axes, metates or grinding stones, and pottery shards. A small number of ground stone gorgets and gaming pieces are included in the collection. Almost all the artifacts are identified with the Pine Mountain region or come directly from the School grounds.

Indian Cliff Dwelling. [indian_cliff_01.jpg]

INDIAN CLIFF DWELLING: Gallery

- indian_cliff_dig_001

- indian_cliff_ee_001

- indian_cliff_ee_002

- Indian Cliff Dwelling with daisy crop to each side. Photo by HHW. [P1130866.jpg]

- Indian Cliff at entrance to School. [kingman_035c]

- Frances Lavender Album. Bonnie Baker, Maude, Virgie Saylor, Minnie Callahan, Hettie Caudill. (Indian Cliff in background.) [lave012.jpg]

- Group at Indian Cliff, Pine Mountain Settlement School. X_100_workers_2646_mod.jpg

- Indian Cliff. _3_general_views_134b_moddian Cliff. General view. II_3_general_views_134b_mod.jpg

- Indian Cliff. General view in winter. [III_3_general_views_134a_mod]

- Indian Cliff. General view with snow. [II_3_general_views_133a_mod.jpg]

- Indian Cliff. Close view. [II_3_general_views_132a_mod.jpg]

- Indian Cliff. [III_3_general_views_132b_mod]

- Indian Cliff Dwelling, general view. [indian_cliff_01.jpg]

See Also:

ARTHUR M. MILLER Biography

INDIAN CLIFF DWELLING “Ancient Relics Discovered by Mountain Girl” Newspaper Clipping

NOTES of the Pine Mountain Settlement School, November 1926

VICTOR K. DODGE Biography

WILLIAM D. FUNKHOUSER Biography

FRED J. BURKHARD Indian Artifact Collection

LOCAL HISTORY SCRAPBOOK Cumberland Gap Past and Present discusses: Mound Builders in Harlan County. [2 pages] Indian mounds ; Cumberland River ; Chattanooga ; Mound Builders ; Native Americans in eastern Kentucky ; archaeology ; Cumberland Gap ; Warrior’s Trail

LOCAL HISTORY SCRAPBOOK Graves of Unknown Dead on Warrior’s Trail” (1922) “Graves of the Unknown Dead. Three Hundred Found On Red Bird Creek Near The Old Warrior’s Trail.” c. 1922. Discusses: Warrior’s Trail ; Shawnees ; Cherokee ; battles ; Cumberland River ; Kentucky River ; Chief Red Bird ; graves ; Battle of Red Bird Creek ; Tahlequah drawings on buffalo bones ; 1655 Indian battle

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF KENTUCKY: AN UPDATE (2008). Vol. One. Ed. David Pollock, KY Heritage Council, State Historic Preservation. Comprehensive Plan Report No. 3.

Back To:

BUILT ENVIRONMENT

|

Title |

Indian Cliff Dwelling |

|

Alt. Title |

Indian Cliff ; Rockshelter ; Rockhouse ; Old Log House Cliff ; |

|

Identifier |

INDIAN CLIFF DWELLING |

|

Creator |

Pine Mountain Settlement School, Pine Mountain, KY |

|

Alt. Creator |

Ann Angel Eberhardt ; Helen Hayes Wykle ; |

|

Subject Keyword |

rockshelters ; students ; archaeology ; burial sites ; skeletons ; epidemics ; excavations ; University of Kentucky ; mattocks ; Indians ; Indian artifacts ; bones ; Indian remains ; Archaic Native Americans ; overhangs ; surface mining ; cliff sites ; explorers ; settlers ; hunters ; livestock ; nucleated family groups ; Isaac’s Run ; crops ; flint ; arrowheads ; axes ; shells ; gorgets ; graves ; University of Kentucky ; Dr. William D. Funkhouser ; zoologists ; Dr. Arthur McQuiston Miller ; geologists ; Mr. Victor K. Dodge ; anthropology ; physicists ; William S. Webb ; paleontology ; Kentucky ; William S. Webb ; Rockhouse ; Greasy Creek ; Middle Fork ; Kentucky River ; flint-makers ; skulls ; Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) ; tribes ; Native Hawaiians ; Secretary of the Interior ; Federal Register ; databases ; grants ; civil penalties ; museums ; regulations ; training ; zoologists ; geologists ; fire-pits ; middens ; funeral songs ; funeralizing ; Howard Carter ; Lord Carnarvon ; King Tutankhamun’s Tomb ; farming communities ; reburials ; Pisgah phase ; Harlan County, KY ; Letcher County, KY ; Perry County, KY ; Kentucky Mississippian period ; Barry Lewis ; grain crops ; pioneer families ; maize agriculture ; Charles C. Mann ; Environmental Education ; artifact collections ; Fred Burkhard ; William Hayes ; pottery shards ; stone implements ; metates ; grinding stones ; axes ; gaming pieces ; Ben Begley ; Southern Appalachians ;; Pine Mountain Settlement School ; Pine Mountain, KY ; Harlan County, KY ; |

|

Subject LCSH |

Funkhouser, William D. |

|

Date digital |

2001-05-27 ; 2013-12-18 ; 2014-01-13 ; |

|

Publisher |

Pine Mountain Settlement School, Pine Mountain, KY |

|

Contributor |

n/a |

|

Type |

Collections ; text ; JPG images ; |

|

Format |

Original and copies of images, documents, and correspondence in file folders in filing cabinet |

|

Source |

Series 10: BUILT ENVIRONMENT |

|

Language |

English |

|

Relation |

Is related to: |

|

Coverage Temporal |

Discovered 1923 |

|

Coverage Spatial |

Pine Mountain, KY ; Harlan County, KY ; |

|

Rights |

Any display, publication, or public use must credit the Pine Mountain Settlement School. Copyright retained by the creators of certain items in the collection, or their descendants, as stipulated by United States copyright law. |

|

Donor |

n/a |

|

Description |

Core documents, correspondence, writings, and administrative papers about Indian Cliff ; clippings, photographs, books about Indian Cliff ; “Indian Cliff,” as it came to be known, was discovered by a student at Pine Mountain. The discovery led to the excavation of the site by Dr. W.D. Funkhouser of the University of Kentucky. This cliff, among many others, comprised the first dwelling Native American inhabitants of the Pine Mountain valley. Today, the cliff and its story figure prominently in the Environmental Education program at the School and the archaeology of the state. The archaeology completed at the site was some of the earliest Native American fieldwork in the state of Kentucky. |

|

Acquisition |

Constructed [year] : n/a |

|

Citation |

“[Identification of Item],” [Collection Name] [Series Number, if applicable]. Pine Mountain Settlement School Institutional Papers, Pine Mountain Settlement School, Pine Mountain, KY, [date]. |

|

Processed By |

Helen Hayes Wykle ; Ann Angel Eberhardt ; |

|

Last Updated |

2002-07-01 hw ; 2004-07-11 hw ; 2013-12-18 hw ; 2014-01-10 hw ; 2014-05-16 aae ; 2015-01-12 hhw ; 2015-12-02 hhw ; 2016-03-27 hhw ; 2019-07-24 aae ; 2022-07-14 hhw ; 2023-07-13 aae ; |

|

Bibliography |

Source Pine Mountain Settlement School Institutional Papers. Pine Mountain Settlement School, Pine Mountain, KY. Archival material. Bibliography Archaeology of Kentucky: An Update. Vol. I & II. Edited by David Pollack, Kentucky Heritage Council, State Historic Preservation Comprehensive Plan Report No. 3. https://heritage.ky.gov/Documents/TheArchaeologyofKYAnUpdateVol1.pdf Canby Jr., William C. American Indian Law in a Nutshell. St. Paul: West, 2004. Print. Spears, Anita, “The Documentation of a Prehistoric Rock Art Site on Pine Mountain in Southeastern Kentucky: An Archaeological Contextual Approach. ” Master’s Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2004. http://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/3325http://trace.tennessee.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=4789&context=utk_gradthes. Accessed 2015-12-02. Carrillo, Jo, ed. Readings In American Indian Law: Recalling the Rhythm of Survival, 1998. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press,1998. [ISBN 1-56639-582-8] Print. Cattell, James M. K. “Funkhouser, Dean William D(elbert): University of Kentucky, Lexington, Ky.” Leaders in Education, a Biographical Directory. (1932). Print. Cattell, James McKeen. “Funkhouser, Dean William D(elbert): University of Kentucky, Lexington, Ky.” Leaders in Education, a Biographical Directory. (1932). Internet resource. Coy, Fred E., Jr., Thomas C. Fuller, Larry G. Meadows, James L. Swauger. Rock Art of Kentucky. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1997. Print. Figgins, J D, and W D. Funkhouser. Birds of Kentucky. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky Press, 1945. Print. Fine-Dare, Kathleen S., Grave Injustice: The American Indian Repatriation Movement and NAGPRA. University of Nebraska Press, 2002,ISBN 0-8032-6908-0. Internet resource. Frequently Asked Questions – NAGPRA, U.S. Park Service. Internet resource. Funkhouser, W D. Arts and Sciences As Taught in the World’s Greatest University. Lexington, KY, 1947. Print. Funkhouser, W D. Autobiography of an Old Man: A Study in Anthropology. Lexington, KY: W.D. Funkhouser?, 1941. Print. Funkhouser, W D. Collected Papers. v.p, 1914. Internet resource. Funkhouser, W D. The Conferences on Graduate Work in Negro Institutions in the South. New Orleans: Office of the Sec.-Treas. of the Conference of Deans of Southern Graduate Schools, Tulane Univ., 1945. Print. Funkhouser, W D. The Days That Are Gone: Some Comments on Extravagance. Lexington, KY: Commercial Print. Co, 1945. Print. Funkhouser, W D. Dead Men Tell Tales: Some Archaeological Fragments. Lexington, KY, 1944. Print. Funkhouser, W D. An Eccentric Egocentric: By W.d. Funkhouser. S.l: s.n., 1940. Print. Funkhouser, W D. The Ethnology Behind the War. S.l: s.n, 1940. Print. Funkhouser, W D. Handbook of Taxonomic Ethnology. Lexington, KY, 1944. Print. Funkhouser, W D. Kentucky Backgrounds. Lexington, 1943. Print. Funkhouser, W D. Kentucky Snakes. Lexington, KY: Dept. of University Extension, University of Kentucky, 1945. Print. Funkhouser, W D. Laboratory Outlines for Zoology. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky, 1927. Print. Funkhouser, W D. An Outline of Bird Study. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky, 1922. Print. Funkhouser, William D. Photo of Staff and Students on Steps of Funkhouser Building. University of Kentucky, n.d.. Internet resource. Funkhouser, W D. Portraits of Kentuckians: Brief Studies in Anthropology, Some Thumb-Nail Sketches of Early Kentuckians Who Were Interesting but Are Not Famous. Lexington, KY, 1943. Print. Funkhouser, W D. Primitive Magic: A Study in Cultural Anthropology. Lexington, Ky, 1946. Print. Funkhouser, William D., Professor of Zoology and Anthropology, Anthropology Department, Dean of Graduate School, Photo of Portrait of Funkhouser Unveiled by Mrs. Hugh Clark Funkhouser (left), Mother of W. D. Funkhouser and Josephine Funkhouser, Wife of W. D. Funkhouser. University of Kentucky, n.d. Internet resource. Funkhouser, William D., Professor of Zoology and Anthropology, Anthropology Department, Dean of Graduate School, Signed by Funkhouser and Dated 1929, Photographer Griswold, Louisville. University of Kentucky, 1929. Internet resource. Funkhouser, William D., Professor of Zoology and Anthropology, Anthropology Department, Dean of Graduate School, Signed by Funkhouser, Not Dated. University of Kentucky, n.d.. Internet resource. Funkhouser, William D., Professor of Zoology and Anthropology, Anthropology Department, Dean of Graduate School, Photographer Kelly Meyer. University of Kentucky, n.d.. Internet resource. Funkhouser, William D., Professor of Zoology and Anthropology, Anthropology Department, Dean of Graduate School, Photographer Adam Pepiot. University of Kentucky, n.d.. Internet resource. Funkhouser, W D. Some Post-War Problems: An Address Delivered Before Kentucky Society of Sons of the Revolution, Lexington, Kentucky, April 19, 1944. Lexington, KY, 1944. Print. Funkhouser, W D. Suggestions for Thesis Writing. Lexington: University of Kentucky, 1943. Print. Funkhouser, W D. Who’s Who in Kentucky. Lexington? KY, 1945. Print. Funkhouser, W D. Wildlife in Kentucky: The Reptiles, Birds and Mammals of the Commonwealth, with a Discussion of Their Appearance, Habits and Economic Importance. Frankfort, KY: Kentucky Geological Survey, 1925. Print. Funkhouser, William. William Funkhouser Photograph Collection. 1942. Internet resource. Funkhouser, W D, and William S. Webb. Ancient Life in Kentucky: A Brief Presentation of the Paleontological Succession in Kentucky Coupled with a Systematic Outline of the Archaeology of the Commonwealth. Frankfort, KY: Kentucky Geological Survey, 1928. Print. Funkhouser, W D, and William S. Webb. Archaeological Survey of Kentucky. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky, Dept. of Anthropology and Archaeology, 1932. Print. Funkhouser, W D, and William S. Webb. The Chilton Site in Henry County, Kentucky. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky, 1937. Print. Funkhouser, W D, and William S. Webb. The Duncan Site on the Kentucky-Tennessee Line. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky, 1931. Print. Funkhouser, W D, and William S. Webb. The Ricketts Site in Montgomery County, Kentucky. Lexington, Ky: University of Kentucky, 1935. Print. Funkhouser, W D, and William S. Webb. Rock Shelters of Wolfe and Powell Counties, Kentucky. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky, 1930. Print. Funkhouser, W D, and William S. Webb. The So-Called “Ash Caves” in Lee County, Kentucky. Lexington, Ky: University of Kentucky, 1929. Print. Funkhouser, W D, William S. Webb, and Angelo I. George. Prehistoric Mummies from the Mammoth Cave Area: Foundations and Concepts. Louisville, KY: George Publishing Co, 1990. Print. Jones, P. Respect for the Ancestors: American Indian Cultural Affiliation in the American West. Boulder, CO: Bauu Press. ISBN 0-9721349-2-1. Print. Lewis, Barry, ed. Kentucky Archaeology. Lexington, KY: University Press of Kentucky, 1996. [Series: Perspectives on Kentucky’s Past: Architecture, Archaeology, and Landscape, Julie Riesenweber, General Editor]. Print. Mann, Charles C. 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus (Second Edition). Viking Press, 2006. Print. Mann, Charles C. 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created, 2011. Print. McKeown, C.T. In the Smaller Scope of Conscience: The Struggle for National Repatriation Legislation, 1986-1990. University of Arizona Press, 2012 ISBN 0816526877. Print. Messenger, Phyllis Mauch. The Ethics of Collecting Cultural Property Whose Culture? Whose Property? New York: University of New Mexico, 1999. Print. Niquette, Charles M. and A. Gwynn Henderson. 1984. Background to the Historic and Prehistoric Resources of Eastern Kentucky. Cultural Resources Series No. 1. Bureau of Land Management, Eastern State Office, Alexandria, Virginia. Print. Nollau, Louis Edward, 1883-1955. n.d. Older man in a chair reading, possibly W. D. Funkhouser. University of Kentucky. Internet resource. “Return to the Earth”. Schlarb, Eric J., and E. Nichole Mills. An Archaeological Assessment of the 610 Ha Croushourn Tracts, Harlan County. Report No. 83. Kentucky Archaeological Survey, Lexington. Schlarb, Eric J., and Ann Schouse Wilkinson. An Archaeological Assessment of Two Tracts (1276 Ha), Blanton Forest State Nature Preserve, Harlan County, Kentucky Report No. 78. Kentucky Archaeological Survey, Lexington. Schock, Jack M. 1977. Comments and Excavation Plan: Structures and Features at 15-HI-304, A Pisgah Culture Site in Harlan County. Ms on file, Office of State Archaeology, University of Kentucky, Lexington. Print. Webb, William S. An Archaeological Survey of the Norris Basin in Eastern Tennessee. Washington: U.S. Govt. Print. Ofc., 1938. Print. Webb, William S. An Archeological Survey of Wheeler Basin of the Tennessee River in Northern Alabama. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1939. Print. Webb, William S, and W D. Funkhouser. The McLeod Bluff Site, in Hickman County, Kentucky. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky, 1933. Print. Webb, William S, and W D. Funkhouser. The Occurrence of the Fossil Remains of Pleistocene Vertebrates in the Caves of Barren County, Kentucky. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky, 1934. Print. Webb, William S, and W D. Funkhouser. The Page Site in Logan County, Kentucky. Lexington: University of Kentucky, 1930. Print. Webb, William S, and W D. Funkhouser. Rock Shelters in Menifee County, Kentucky. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky, 1936. Print. Webb, William S, and W D. Funkhouser. The So-Called “Hominy-Holes” of Kentucky. N.p., 1929. Print. Webb, William S, and W D. Funkhouser. The Tolu Site in Crittenden County, Kentucky. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky, 1931. Print. Webb, William Snyder, and W. D. Funkhouse. 1936. The University of Kentucky reports in archaeology and anthropology. Lexington: Dept. of Anthropology & Archaeology. Internet resource. Webb, William S, and W D. Funkhouser. The University of Kentucky Reports in Archaeology and Anthropology. Lexington: Dept. of Anthropology & Archaeology, 1936. Print. Webb, William S, and W D. Funkhouser. The Williams Site in Christian County, Kentucky. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky, 1929. Print. Webb, William S, W D. Funkhouser, and Hans T. E. Hertzberg. Ricketts Site Revisited: Site 3, Montgomery County, Kentucky. Lexington, KY: University of Kentucky, Dept. of Anthropology and Archaeology, 1940. Print. |

Return To:

BUILT ENVIRONMENT