Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 07: DIRECTORS

Glyn Morris

Change in the Mountains Affecting Opportunities, c. 1937

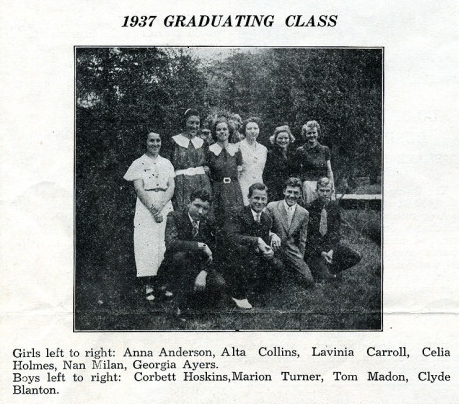

“1937 Graduating Class,” excerpted from May 1937 Pine Cone. [pmss_archives_pinecone_class_1937.jpg]

GLYN MORRIS 1937 [Change in the Mountains Affecting Opportunities]

INTRODUCTION

In 1937 the changes in the mountains were dramatically affecting opportunities for youth in the Appalachian coalfields. This was particularly evident in Harlan County, Kentucky, where Pine Mountain Settlement sought to provide quality education for youth. Director of the School, Glyn Morris, wrote this small “resume” on September 28th, [most likely 1937] shortly after the opening of the school year at Pine Mountain. It is a thoughtful essay addressed to the governing Board of Directors of Pine Mountain Settlement.

The paper articulates a recurring theme with Morris: how best to address educational needs within the growing industrialization of the rural Central Appalachians of Kentucky, and specifically, Harlan County. The mushroom-like growth of mining camps that sprang up during the frantic efforts to supply the fuel needs of World War I and II, introduced a shift in population in the large county of Harlan. Both coal booms resulted in a declining population of eligible students drawn from the near-by rural and non-mining communities. As all settlement schools began to draw from the same dwindling local rural populations, an increasingly larger student body was recruited from the growing number of transient coal town populations that had rapidly proliferated during WWI and WWII. The transient nature of these coal town grew rapidly but they also lost population just as rapidly as coal either “boomed” or went “bust”. During the Great Depression many of the camps in Harlan County declined as the economic depression grew in the mountains and there were few opportunities elsewhere.

The “boom-bust” cycle was to continue for years, not only within the mining towns but throughout the region. Mining families and subsistence farmers alike scrambled to feed, clothe, and educate their children in a roller-coaster economy that was co-dependent. The very rural areas surrounding the Settlement School had been the early focus of need that settlement schools in the area addressed, but that focus was rapidly shifting just as Glyn Morris assumed the Director position at Pine Mountain Settlement in 1932. In this paper he calls the Board’s attention to the rapid changes occurring and he challenges them in this paper to consider a variety of educational options.

The main question that Director Glyn Morris put forward to the Board of Trustees of the School was “In what manner can Pine Mountain function so that it may conserve all its inherent values, meet a real need, be more self-supporting, and have an honest and worthy appeal?” It was not the first time this question had been floated, nor would it be the last, but the need for an educational re-think was at a critical point in 1937.

In this paper Morris explores a variety of possible programming options including an expansion of the School’s industrial training programs, the conversion of the High School program to a Junior College environment with an emphasis on practical skills, and a hybrid approach that would pull ideas from both and stagger the tuition demands based on the programs and the level of instruction.

The over-arching issue that Morris returns to throughout his brief resume is that of a balanced economy of scale for the institution. Increasing tuition, possibly charging more for advanced training, aiming for a slight increase in student population, and returning to the utilization of teacher-training programs to reduce staffing costs, are explored by Morris. His ideas are put forward, not as fully formed solutions to the School’s shifting problems, but as a call for other ideas and a request for a consensual move forward by the Pine Mountain Settlement School Board.

Morris looks both forward and backward for answers to the institution’s growing deficits. For example, he returns to the idea of bringing educators into the school for training programs such as that provided by Antioch College‘s teacher training program, used in earlier years. But, whether looking backward or forward, Morris remains focused on the institution’s mission to serve the community and provide programs for the “needy student”, whether local or from the growing coal camps. The focus was on under-served rural populations. Morris returned to this focus throughout his career and not just in Kentucky. Throughout his life, he wrestled with how to provide not just education, but quality education, to rural and disadvantaged populations.

The following is a full transcription of his brief but important resume which he submitted for consideration to the PMSS Board of Trustees. While his resume is not dated, all signs point to 1937. The hand-written note at the top of page one suggests this to be the year he drafted the document.

A later paper written by Morris in 1937 again describes the growing challenges of educating in rural America, but in greater detail. He pushes forward with the ideas found in this brief paper and he particularly contrasts them to the “standard” educational models in current use. The later research paper, “Is There Any Further Need of a School Like Pine Mountain Settlement?” picks up his early themes again and makes an even stronger argument for a multi-tiered educational experience for students. He points to lessons learned as the Director of Pine Mountain and to the growing body of evidence published by other educators. He cites the work of individuals who were influenced by Progressive educational theories, particularly those of John Dewey.

At Union Theological Seminary in New York City, Morris majored in “Church and Community” and minored in “Religious Education.” His fieldwork, part of his required training at Union Theological, was under the supervision of Professor Arthur L. Swift, who headed the new department of Church and Community. Union was undergoing a rapid change away from the Systematic Theology of the earlier years and pursuing a more contemporary model such as the work of Paul Tillich’s Existential Philosophical Theology and Rheinhold Niebuhr‘s so-called Neo-Orthodox or Realist Theology. Both Tillich and Niebuhr were faculty at Union.

Church and Community had a large impact on Morris and he often looked to the influences of Union Theological, especially the supervision of Arthur L. Swift. He also explored and questioned deeply the religious and philosophical transition period at Union Theological Seminary in his book, Less Traveled Roads (Vantage Press, 1971). He credits Arthur L. Swift with opening his mind to new ways to address education and Swift was an important consultant for Morris particularly in 1937, a low point in Morris’s career. When Morris contemplated leaving Pine Mountain in that year, he sought the counsel of Swift, finally deciding that staying was a better option. The enthusiasm of the early years, particularly following his training at Union and arrival at PMSS in 1935 Morris is seen as fully engaged and looking for ways to enhance the school program at Pine Mountain and he says of that period

As my interest grew in the educational program at Pine Mountain, and while I kept pushing for changes, I was being affected by the point of view expounded by Professor Brewer [John Marks Brewer] of Harvard University in his book Education as Guidance. [FULL TEXT]

Morris, Glen. Less Traveled Roads, Page 140

Also in 1935 Morris has discovered another source of inspiration. He met and made an important connection with “a remarkable woman,” Dr. Orie Latham Hatcher, an expert in the role of guidance in education and founder of the Southern Women’s Educational Alliance, later known as the Alliance for Guidance of Rural Youth. By 1937 Morris was deeply engaged with Hatcher and with the Alliance for Guidance of Rural Youth. This interest was to bring him back to Harlan County Schools following his departure from Pine Mountain Settlement in 1942.

In 1937 he had hit a low point regarding his approach to education and despair caught up with him. Yet, he persisted in seeking to address education in rural commuities. Writing in 1977, some 40 years after his years at Union Theological, his experience at Pine Mountain, and his years in rural New York schools, Morris suggests that the ideas of Dewey “never caught on” and “was grossly misunderstood by many educators,” and that he had learned much from and was clearly intrigued by the educational theory of John M. Brewster and his views of community’s role in education. He reflected on the importance of community to the educational cycle and recalled what he often said to teachers

‘When Johnny comes into the classroom, he brings with him his father, mother, brothers, sisters, grand-parents, even the work he has to do around the house, and the teacher has to be aware of these factors in order to successfully get to him.” This is not to say that content of curriculum is not important. It simply means that in order to get the content across to the youngster some attention must be paid to the youngster as a person who is susceptible to many forces, and that it follows logically then that guidance requires that a good record be kept of the child, i.e. the school be in possession of all the knowledge available about him, and that this knowledge be used in passing judgment on him at any time. It also means that there be available to him one person, either a counselor or a teacher, who knows him as a whole … that education is really guidance of the pupil toward specific goals which he has helped formulate and are compatible with his abilities, and include all the factors which have brought him to where he is.

Morris, Glen. Less Traveled Roads, Page 140-141

TRANSCRIPTION [CHANGE IN THE MOUNTAINS AFFECTING OPPORTUNITIES] * Note: No title given to the paper

A handwritten note at top of page: “History paper 1937-38”

page 1

The resume, issued on September 28th, of change in the mountains affecting opportunities in secondary education revealed that the private secondary school is duplicating public education to an extent that makes its continuation as such largely unnecessary. It further revealed that only a small portion of our students come from the rural vicinity of the School — the large portion comes from along the highways served by county school buses.

The question to which the Board of Trustees must now direct its attention is — In what manner can Pine Mountain function so that it may conserve all its inherent values, meet a real need, be more self-supporting, and have an honest and worthy appeal?

At a meeting in Lexington, in December, [year? 1936 ?] Mr. [C.N.] Manning, Mrs. [Fannie] Gratz, and Mrs. Bullock suggested that steps be taken to investigate the need for Pine Mountain to serve particularly in the field of vocational training at the high school and post-high school level. Since that time a committee has been working steadily with a view toward making recommendations to the Board of Trustees as to the area of service that Pine Mountain might accept as its own for the future. At the present time, a survey is being made by Pine Mountain Settlement School of the youth of Harlan County, both in school and out, as a basis for the recommendation. This survey is not complete and it is yet too early to make

page 2

accurate predictions. However, from the substance of our discussion together as a committee, our thinking is beginning to fashion itself along the lines indicated below, while we keep constantly in mind the question stated above.

IS THERE A NEED?

The public institutions of the state and county are assuming responsibility for providing education to the elementary and secondary levels. While only a small percentage of rural boys ad girls (in towns of 2,400 or under) remain in school until they complete the 12th grade, the task of adjusting public education to meet their needs so that more will remain until satisfactory completion of high school is not our immediate problem except as we make our curriculum an example of the kind of curriculum that will keep young people in school for a longer period of time. However, I think we should recognize that there is an area involving many young people for whom formal education has not provided the experience and training which they need, with the result that many are poorly prepared to meet the demands of existence in modern society. Your attention has previously been called to the FINDINGS OF THE RURAL YOUTH GUIDANCE INSTITUTE, held in Washington, November 1-3, 1937 (p, 7), which indicated the need for providing vocational training for older rural youth and suggested methods of providing such training. Much thinking is being directed toward

page 3

the problem of providing further education and training for the 2,000,000 rural youth who cannot be absorbed on the land and who drift to “blind alley” occupations in urban centers. At the beginning of 1937, there were perhaps three to four million young people who were through with school but unable to find a full-time job. Although no figures are available — we can safely assume, based on past experience, that the mountains have their full quota of these youth. Sooner or later we shall all have to face the fact that something must be done for the young people between the years of eighteen and twenty-one who are not going to be absorbed in industry and for whom the only possible solution under present conditions is to provide further schooling either on a full-time or part-time basis. The President’s Advisory Committee on Education reported that “Millions of young people are neither in school, at work, nor obtaining any type of experience that might prepare them eventually for work.” The American Youth Commission has “accepted the postulate that society is responsible for the care of all young people until they can find employment up to the age of twenty-one”, and that beyond sixteen “vocational training should be provided for those who want it, and adequate facilities for the further education of those of an academic and intellectual bent”, It seems that in a general way, Pine Mountain’s future field of service lies with the youth of later high school and post-high school years. How

page 4

acute is this need in Harlan County we do not know. We hope for the survey now being conducted to secure the data which will indicate the particular area of this need.

DEFINITION OF OUR AREA

In thinking of Pine Mountain’s work in the mountains, the question comes up again and again, “How much good are we actually doing?” Thus we enter into the baffling problem of evaluating our work. Not even the beginnings of an adequate measuring rod exist. We can only conclude that those individuals who have spent a reasonable amount of time here have been influenced by the life of the School is diffused. Would it not be more expedient to select a limited area such as Harlan county and as much as possible to confine the work of the School to that area, so that by the very weight of numbers its influence would be felt and the possibility of social change brought theoretically at least, closer to realization?

THE PROBLEM OF FINANCE

Two factors have been responsible for the decrease in contributions to the work of the School:

- The general decrease in money available for charitable work.

- The effect which improved conditions in educational opportunities on the secondary level in the area has had on the content of the appeal for funds.

page 5

During the six years prior to 1936-37, the School has operated on $56,000 less than for the previous six years. With the School set up on the cottage plan, with its scattered housing and its partially self-subsisting-operated-by-student-basis, there is a point of minimum expenditure below which the School cannot be maintained. Further trimming of the staff is impossible if the work is to be continued on anywhere near an efficient basis. An examination of the School records will reveal that, numerically, the present staff is the lowest in the history of the School for the number of students enrolled.

In this connection, it should be pointed out that the School would operate with a maximum return on investment with the addition of more students. This is illustrated by the following chart.

page 5a

Graph Showing Relationship of Number of Students to per Capita Cost [SEE CHART IN GALLERY]

page 6

It is the feeling of the Committee that much more of the Schools’ support should come from the local area, and particularly through the students themselves, and that the School’s program should be gradually modified so that it increasingly approaches this goal. At the present time, our students pay only tuition of $50.00 per year. Only fifty percent of the students pay this, the rest working their entire fees out through the summer months. It is felt, however, that approximately 75% of the student body of the future should pay at least $150.00 for advanced work. Objection may be raised to this on the ground that it will exclude needy students. If we allow however for 25% of the student body to come on a scholarship basis, and the increase of student enrollment, we shall be able to take care of the actual number who apply and are worthy and who can benefit by the training which Pine Mountain can give.

Much of our problem centers around finding a sound basis for appeal No plan which we adopt for the future can ignore the fact that it must be of such a nature as to appeal to people who are already hard-pressed by appeals from many quarters. I believe that essential to a strong appeal in the future for a project of this kind will be that we are pioneering educational philosophy and method with emphasis on the problems of the locality. We would not seek to subservient our program

page 7

to an appeal — but it follows that a new and vital educational program is per se a strong appeal. It challenges those who are in a position to give and who desire that their gifts shall be used not only to ameliorate but to build for the future The field of post-high school training, aside from regular college work, is one which will command increasing attention and one in which comparatively little is being done. Pine Mountain offers, with its heritage ad equipment, an excellent laboratory for such work.

Furthermore, it is believed that the simple, wholesome life of Pine Mountain will have an increasing appeal to those who are already yearning for a culture that is free from much that is superficial and of only passing value.

THE COMMUNITY

Any discussion of Pine Mountain’s function must include the area in the immediate vicinity of the School. A glance at the chart showing the homes of Pine Mountain students reveals that only a small percentage of the boarding students (less than twenty) come from the immediate vicinity of the School. This is not a recent development but has been the case for at least ten years ad probably has always been true The majority of our students come from along the highways in Harlan County. Because of the scattered, submarginal nature of our community, it has been difficult to do much except in individual cases, themselves so scattered as to make no perceptible impression on the community itself. Authorities hold little hope of any real betterment of conditions in our area because the

page 8

land cannot support the number of people who are living on it, and increased usage continues to deplete the resources. Whatever improvement that might come, must come via the inspiration and leadership of the School. We have already begun a well-organized and systematic community program which we believe promises much both for the community and for the School, Through its older students the School is reaching into the community in a very concrete way, and at the same time providing very practical training for the girls who carry o the program. In so doing, Pine Mountain is helping to blaze new trails in practical education. Thus the community, through our present program, and we hope through expansion of the present program, will be drawn closer to the School.

BRIEF SUGGESTIONS FOR CONSIDERATION IN THE PROGRAM OF THE FUTURE

I. Junior college with especially thorough terminal vocational courses selected from the following:

| Printing | Home Economics |

| Business | Mechanics |

| Carpentry | Agriculture |

| Practical Nursing |

The entire curriculum built around the 10-14 grade plan and flexible enough to admit promising students who have not completed high school but who wish vocational train-

page 10

ing. With an accredited school, it is quite likely that many day students from Harlan, Benham, Lynch would take advantage of Pine Mountain. In this connection, it is well to note that Pine Mountain has already many advantages for a junior college. Pine Mountain can also help to remove the temptation to work in the mines, broaden occupational horizons, and help to encourage ideal for local service.

II. A miniature Antioch Plan which would enable about a dozen students to go by bus daily to Harlan and there receive periodical training in local industry ad business. Another dozen would alternate at the end of a six-week period.

III. Possible arrangement with state teachers college whereby teachers are trained in rural work under the guidance of Pine Mountain. Seven local schools would provide excellent laboratories for such training.n

IV. In application with some larger hospital, train and develop rural nursing school for practical nurses or “nurses aides”.

The above are only suggestions and have not been examined thoroughly as to their practicality.

- Of special note: In 1963 Glyn Morris was invited back to Harlan County to be the Guest Speaker at the 25th Anniversary meeting of the Harlan County Institute. This Institute was still utilizing parts of the robust program initiated by Glyn Morris and O. Latham Hatcher that was originally the Guidance of Rural Youth program and later known as the Harlan County Rural Youth Guidance Institute.

GALLERY: [Change in the Mountains Affecting Opportunities]

- 001 morris_changes_in_mountains_sept_001

- 001 morris_changes_in_mtns_001

- 002 morris_changes_in_mtns_002

- 003 morris_changes_in_mtns_003

- 004 morris_changes_in_mtns_004

- 05a morris_changes_in_mtns_005a

- 06 morris_changes_in_mtns_006

- 007 morris_changes_in_mtns_007

- 008 morris_changes_in_mtns_008

- 009 morris_changes_in_mtns_009

Back To: GLYN MORRIS 1931 – 1977 Guide to Talks, Writing and Publications

SEE ALSO:

Brewer, John Marks. The Vocational-Guidance Movement, Its Problems and Possibilities. New York: Macmillan, 1922. Print.

ORIE LATHAM HATCHER Consultant

RURAL YOUTH GUIDANCE INSTITUTE Recommendations 1937