Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 07: DIRECTORS

Series 13: EDUCATION

Series 25: STUDIES, Surveys, Reports, Consultants

Glyn Morris, Director

Harold Spears’ Question:

Is There Any Further Need of a School Like

Pine Mountain Settlement School?

c. 1937

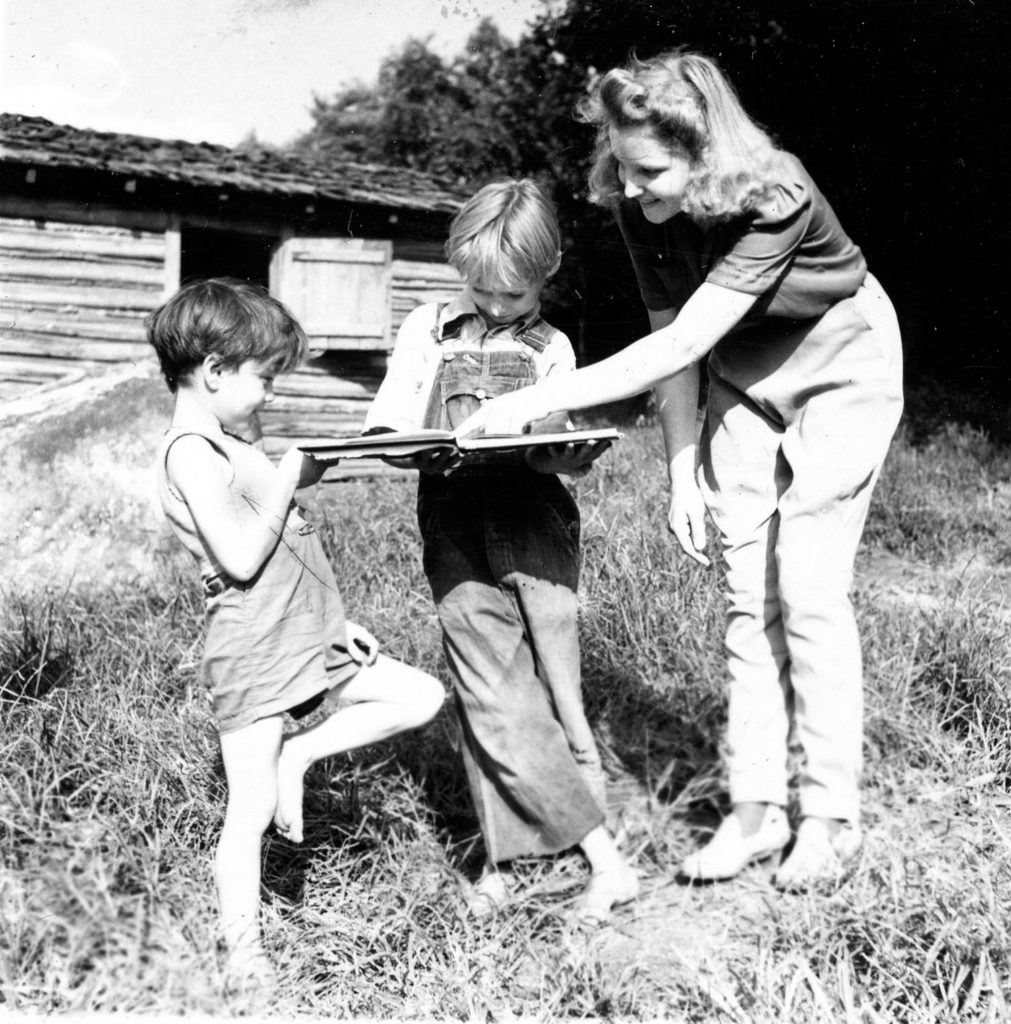

Ruth Shuler, PMSS student, bookkeeper, teacher, 1937-44. With two children sharing traveling library delivery in the community. [pm_garner_118]

TAGS: Glyn Morris, Pine Mountain Settlement School, institutional mission, Harold Spears, Walter H. Gaumnitz, education, one-room school, settlement schools, teachers, economics, coal towns, transportation, industrial training, school busing, teacher salaries, Malcolm Ross, Machine Age in the Hills 1933, L.C. Gray, Great Depression, educational reform, Rural Youth Guidance Program

GLYN MORRIS 1937 and HAROLD SPEARS Question:

Is There Any Further Need of a School Like Pine Mountain Settlement School?

While the author of this position paper was not identified on the copy, it is most certainly Glyn Morris with the consultation of staff member Everett K. Wilson and Wilson’s publication, A Study in Civics, 1937. It was most likely motivated by the visit of well-known educator Harold Spears. This would place the date as 1937 when Spears stopped at Pine Mountain and spoke with Morris regarding the innovative educational experiment that Morris initiated in the last years of his tenure as Director of Pine Mountain Settlement School, It was during these late 1930s years that Morris also struggled with the question of Pine Mountain’s educational needs and its future during the years just preceding WWII.

Further exploration of the archival collections has revealed the date and the details surrounding the production of this thoughtful reflection on the mission and the direction of the mountain settlement school. The probable date of this position paper seems to point to1937, during a particularly difficult time in Morris’ tenure as director. It was a well-documented period of upheaval in the Appalachian coalfields that had major implications for the Pine Mountain Settlement School. It was also an important transitional period for Secondary education across the country as educators began to retreat to the oppositional camps of Progressives and Essentialists. As Glyn Morris and Harold Spears both wrestled with the growing educational division and watched the developing events in Europe, there was a mutual need to re-invent secondary education and especially as it impacted the country’s rural youth.

As an educator of growing importance, Harold Spears had a nagging concern regarding the education of America’s high school youth. He began to look at innovative programs throughout the country in an effort to determine what was working and what was not. The year was 1937, and the program at Pine Mountain had come to his attention. When he made a visit to the campus during that time, he and Morris were certainly of much the same frame of mind. Further, both educators had been influenced by the recent publication of a book that surveyed the many problems – economic, educational, and social – that were re-shaping Appalachia. As the center of coal mining, the region was creating massive upheaval in the lives mining families, particularly in the county of Harlan. The book that raised concern was Machine Age in the Hills by Malcolm Ross.

GLYN MORRIS AND MALCOLM ROSS: MACHINE AGE IN THE HILLS

Morris appears to have been strongly influenced by many of the issues that appeared in Malcolm Ross’s 1933 book, Machine Age In the Hills. It is very likely Spears also knew the book. Further, a similar discussion regarding social welfare, economics, employment, and most importantly, education, had been raised in the earlier 1933 Annual Conference of the Southern Mountain Workers and was published in their small journal Mountain Life and Work Vol. 9 N. 2, July 1933. As a member of the Council of Southern Mountain Workers, Pine Mountain Settlement School regularly contributed to the dialogues generated by the members of that formative and Progressive organization. Morris would later lead the Council for a brief time in 1943 following his departure from Pine Mountain. While a Director at Pine Mountain Morris frequently quoted from the proceedings of the Council and also contributed to the publications of the organization prior to his leadership.

While the exact date of the paper at the center of this commentary is not known, it has many elements that place it within the tumultuous coal wars in Harlan County. Morris’s papers continue to have date identity issues, but there are clues to dating of the work. It appears to reflect the late years of the 1930s — post Great Depression. The extensive references to Malcolm Ross’ book, Machine Age in the Hills, (1933) pairs well with the state of mind of the apparently beleaguered Director. Morris’s deep introspection of the educational program at Pine Mountain Settlement was in direct proportion to the personal introspection that seemed to be going on within Morris and the School’s teaching staff during the later 1930’s.

The conflicts and confusion, generated by the increasing social changes at the local level and the growing political changes at the National level, obviously called for changes in the local educational framework. In the mind of Morris those changes suggested a deep re-assessment of the educational mission of Pine Mountain and of the many regional independent schools. Re-assessment was overdue. The sea changes in education beginning in the mid-1930s had, by the late 1930s, unsettled most educational institutions throughout the coalfields of the Central Appalachians as well as many rural areas of the country. The “Machine Age” had come to the hills and Morris was concerned that his institution was not keeping pace.

When Harold Spears visited the campus, Morris was primed for their conversations. Both men found an empathetic listener. Was it Progressives or was it the Essentialists who were creating the issues? Do schools address science or sentiment? Was Pine Mountain an “isolated social research laboratory”?

Malcolm Ross opens his book with a chapter titled, “Sentiment and Science” in which he gloomily ruminates,

“A machine age twilight has settled over the coal hills of the South. There, during the past two decades, a region of small farmers was made momentarily prosperous by a sudden invasion of industry; then the wave passed, leaving them split from the old way of life and helpless to face the new. Here, in miniature, is a cycle which technology seems to be working out in America at large . … in the coal fields, we have an isolated social research laboratory where we can examine the already completed cycle from agrarian stability to industrial collapse.”

Harlan County was one of the most intense laboratories in this grim national picture of social and economic degradation. In the opening chapters of his book, Ross could almost be walking alongside Morris as he ventured out into the rural communities around Pine Mountain School and in the hollows being mined along Big Black Mountain. Ross continues

We cannot forecast the effects of technology in all the interlocking industries of the United States. But in the coal fields, we have an isolated social research laboratory where we can examine the already completed cycle from agrarian stability to industrial collapse.

In so doing we are struck by the persistence of the old patterns of bungling and bloodshed. This, we had thought, is a scientific age; yet we act as though no better tools than tooth and claw had ever been invented. Inside our laboratories we know how to apply the scientific spirit; but when we take the results of research into the market place we squabble over them in emotional restraint.

Ross heightens the dangers of these “squabbles” that start to sound all too familiar:

… In this there is grave danger, since technology is an impersonal factor, not answering to emotional treatment. Its tendency is to put men out of work faster than we can succor them, and it does this quite independently of human moods.

This phenomenon has long been under observation. Morose prophets have been predicting for a decade that machines would eventually create a surplus of human hands for which society will never be able to find work. Others supposed that increased production could keep pace with technology.

The argument was still in progress when the economic cataclysm of 1929 produced such a vast unemployment that it became a matter of small concern whether or not a man was in the breadline because a machine had put him there.

Some day, however, that question must emerge again into reality, and the answer will be of first importance. … The point is closely linked to our emotional attitude toward the jobless. The notion of America as one big family implies that the luckier ones will dig into their pockets to carry the others over the emergency….. But suppose that we are mistaken …

But suppose that we are mistaken ……

As Ross continues to cast his sharp eye on the social ills of Appalachia in the late 1930s, the rest of America was shifting rapidly. This social assessment of Appalachia continues today and Ross’s observations are even more relevant and possibly bleaker in an age of AI. Still, his assessments lack full educational credibility when measured against the regional realities. He seems uninformed when he continues to refer to the mountains of West Virginia and the Cumberland Plateau, as the “Blue Ridge Mountains,” and the people as the “Blue Ridge” people but still considers it coal country. His descriptions of the people in this mis-identified geography, which clearly was not the only national region suffering similar stress, is painted with a broad brush and is inadequate for those who may wish to give his ideas deep attention.

Today, his very broad and denigrating portrait of the region is reviewed as detracting from the ideas and lessons that continue to ring true for the region in his many other social assessments. Whether Ross had direct familiarity with Harlan County in the late 1930s, is not known, but we do know that the educator Harold Spears (The Emerging High School Curriculum and its Direction, 1941) had some interesting observations that run counter to Ross. Spears gathered his ideas by conducting his investigation on site and who could forget the names of the mountains he actually had to cross to get there.

DR. HAROLD SPEARS Visits Pine Mountain

Educator and author of the influential book, The Emerging High School Curriculum and Its Direction, Feb. 1, 1941. (First published 1940 ?) and Influenced by MORRIS.

Allen, C. F. (1940). A Review of New Curriculums in Action. The School Review. https://doi.org/10.1086/440587 [Reviews the new book by Spears.]

[See: Spears, H. (1942). Comments to Beginning Teachers. Teachers College Record. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146814204400309]

While reference to the work of Ross appears frequently in Morris’ writing, there is no indication that Ross ever visited Pine Mountain. Dr. Harold Spears, formerly the Principal of the Springdale, Illinois Schools System and later Superintendent of Schools in San Francisco, California, and later faculty at San Francisco State College, did, however, visit Pine Mountain Settlement School. He was also familiar with the work that Morris was attempting to initiate at the remote mountain school. See for example

Spears, H. (1963). A Second Look at “The Emerging High School Curriculum”. The Phi Delta Kappan, 45(2), 101-103. https://doi.org/20343045

Harold Spears arrived at Pine Mountain in late 1930 as part of a tour of the Appalachians. The visit was ground-breaking for both Spears and for Morris. Following the visit of Spears Director Morris took a hard look at the net results of the Pine Mountain Settlement School educational program with its cost of some $50,000 annually. What he saw and what was confirmed by Spears was that the experimental program at the School was failing to make an impact on the broader community that it served. The realization that Spears may well have called it correctly and the supporting evidence in support of that view, appears to have been profoundly unsettling for Morris.

Director Glyn Morris, who, even in his early tenure at the institution, had begun to question the goals of the settlement school and of similar private secondary and college programs in the mountains. He had felt that the goals were not keeping pace with the times. The new book by Malcolm Ross, while incomplete in its assessment of the region, agreed with Morris’s social and economic views, but the educational assessments of Spears were closer to the looming educational problems of the region. The visit by Spears appears to have been a pivotal point in Morris’ administrative and educational trajectory. It helped that Spears and Morris were much more aligned. The interest shown to Morris’s educational direction was reassuring,

Following the visit of Spears to Pine Mountain Settlement School he wrote of his conversation with Morris regarding student outcomes. He notes that Morris acknowledged the shortcomings of the Pine Mountain educational program for regional retention of the graduating population.

Eventually, unless he leaves the mountains, the student returns to a situation alien to his schooling. Everything is against him. Furthermore, little opportunity is given our more mature students to develop leadership and initiative under real-life conditions. And, too, the young people of the mountains should have an active share in solving the pressing problems which they as a group must face. After they are through college it is too late. They have been trained away from the mountains, or in their desire to get to the top of the heap, they unconsciously aim at positions which mark then off from the life and problems of the folk from which they have come.

[Spears, Harold. The Emerging Highschool Curriculum and Its Direction, American Book Company, New York, 1940… Chapter 4 of the book is devoted to the Pine Mountain visit.]

This trope soon became a familiar one in higher educational institutions throughout the Appalachian region. As a higher education institution Berea College was particularly sensitive to the migration of youth out of the region. Morris cites one school, the John C. Campbell Folk School at Brasstown, that he saw as seemingly successful at the time. It had been especially successful in integrating the community with European educational experience. Morris then forges ahead with what he sees as a remedy to the Community around Pine Mountain Settlement and its educational dis-join. His remedy was to institute a guidance program that would be shared within the educational program and would be county-wide.

Morris’s suggestion that both programs would be shared with the broader county educational community. It was an innovative move supported in part by new ideas gleaned from the Columbia University Educational innovations. He adjusted the local Pine Mountain curriculum to include vocational education, and he further strengthened his outside educational networking. Critically, he enlisted the aid of Dr.Orie Latham Hatcher, whom he had met at the Southern Mountain Workers Conference in Knoxville in 1935, and the assistance of Dr. Ruth Strang a Columbia University psychologist, educator and leader in rural youth education. With these experts in his circle of advisors, Morris began his march to reform and revitalized his Pine Mountain educational experiment.

The Rural Youth Guidance Institute was born. Both Hatcher and Strang were indebted to the educational work of John Dewey and to his so-called “Live Creature” idea. And, both were deeply interested in Morris’s Pine Mountain experiment and recent endorsement by Spears.

Life itself consists of phases in which the organism falls out of step with the arch of surrounding things and then recovers unison with it — either through effort or by some happy chance. And, in a growing life, the recovery is ever more returned to a prior state, for it is enriched by the state of disparity and resistance through which it has successfully passed. If the gap between organism and environment is too wide, the creature dies. If its activity is not enhanced by the alienation, it merely subsists. Life grows when a temporary falling out is a transition to a more extensive balance of the energies of the organism with which it lives.

[McDermott, John J. The Philosophy of John Dewey: Two Volumes in One, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1973, 1981. p.xxix.]

WALTER H. GAUMNITZ and the One-Room Schools

Enter Walter H. Gaumnitz, the third educator whose ideas permeate the following position paper by Morris. Gaumnitz was also a leading figure in education during the 1930s and a leader whose central focus was rural education. He made a strong impression on Morris who returned to the ideas of Gaumnitz’s educational writing time and again for inspiration. As Morris began to think deeply about the plight of rural youth in the region, he set about to develop a program for rural youth in Harlan County. That effort resulted in the county-wide and eventual region-wide Rural Youth Guidance Institutes.

The following paper brings together the thoughts of Morris as he struggled with the question —“Is There Any Further Need of a School Like Pine Mountain Settlement School?“

Editor: H. Wykle

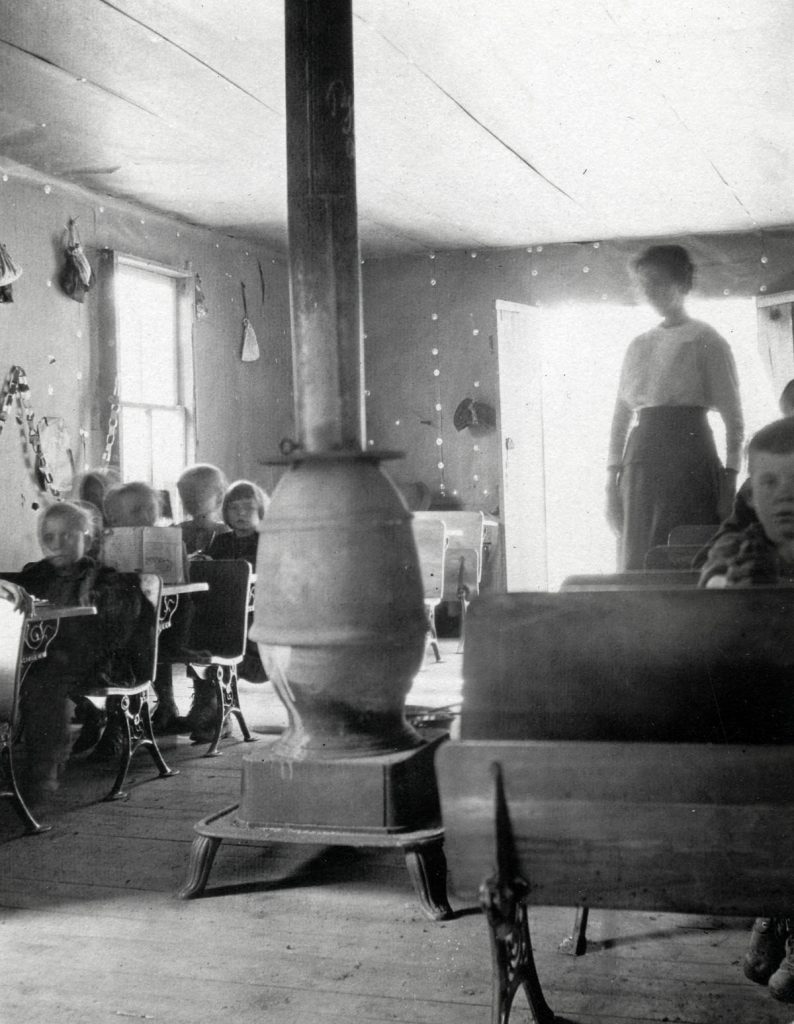

“Alex Branch School, 1948.” Interior of a classroom with children, teacher.” Photographer: Arthur Dodd. [nace_II_album_077.jpg]

TRANSCRIPTION

p.1

GLYN MORRIS

“Is There Any Further Need of a School Like

Pine Mountain Settlement School?”

[Reflections on Machine Age in the Hills by Malcolm Ross (1933) and other indicators of change in education in the Southern Appalachians.]

The following paper grew out of a quite natural confusion in the minds of the members of staff, as we tried to think through a practical solution for a complex problem. It is an attempt to state as clearly as possible our problem. It considers some of the factors involved and our method of meeting the problem. It is by no means final, but It forms a basis for discussion and for further thinking for the members of the staff and the Board of Trustees.

In view of the social change and growth which has taken place in our section of the mountains during the past twenty years, the question arises more and more frequently as to whether or not there is any further need of a school like Pine Mountain Settlement School. Contrary to what has been commonly assumed “There is comparatively little difference between the number of children reached by public elementary schools in the mountain areas and non-mountain areas.” (Gaumnitz: “Education in the Southern Mountains,” Bulletin 1937, no 26, U.S. GPO, Washington, DC 1938) and Walter H. Gaumnitz, “Extent and Nature of Public Education In The Mountains, “Mountain Life and Work, July 1933). The past twenty years have witnessed the growth of elementary and secondary schools all through the mountains, as well as the building of many miles of concrete highways. But we cannot dismiss this question by simply saying that there are more schools now than there were twenty years ago and that there are many miles of paved highway where there were only wagon roads twenty years ago. For that matter, there are still large areas where there are no high schools and where there are no highways. For example on the north side of Pine Mountain, from Pineville nearly to Whitesburg, a distance of sixty miles, there are no paved roads and no public high schools. Nearly all of Leslie County from the southern border to Hyden has no paved road and no high school.

p.2.

The question also involves consideration of the fact that Pine Mountain Settlement School is maintained at considerable expense by contributions from people who know very little about mountain conditions of the present day, and who are perhaps drawn to support the work almost wholly through sentimental impressions created twenty years ago. Again we must keep in mind the detrimental concomitant effects of a work of this sort — for undoubtedly many mountain people use the school primarily as an economic refuge and not primarily for education. Finally, there is the question of our assuming a very fundamental obligation which rightfully belongs to the state.

In seeking an answer to our question we must consider two aspects of education — quantity, and quality, with particular emphasis upon the latter. And no answer can begin without keeping in mind a social and economic picture of the area under consideration.

From 1910-1930 the population of Harlan County increased from 10,566 to 64,557 or 510%; the population of Letcher County increased 236% and Perry County 274%. (U.S. Census, 1930) These are the coal-producing counties of our area. Most of the increase in population live in coal camps. This fact alone has created a social and economic problem of some proportion, a good picture of which is given in Machine Age in the Hills [1933] by Malcolm Ross, and about which nothing yet has been done by the social agencies of the state.

L.C. Gray, in a summary report given before the Conference of Southern Mountain Workers of the economic conditions and tendencies in the Southern Mountains, (Mountain Life and Work, Vol. 09, no. 2 July 1933) says,

The past thirty years has been a time of rapid transformation. Population …

p.3.

in the region has increased about 56%. The heavy increases were in the coal-producing counties of eastern Kentucky and southwestern West Virginia. [Furthermore,] on the other hand, in many of the isolated rural counties of poor natural conditions for farming and without any industrial or mining developments, the country population remained stationary or even increased somewhat.

Along with this goes the fact that there has been a decrease in the total farm and crop area, and a birthrate continues nearly two and a half times what is necessary for a stationary population.

0041b P. Roettinger Album.” Little Laurel Schoolhouse.” (18 people: six children and one man on top of roof, eleven standing in front of building.) [roe_041b.jpg]

It needs no argument to convince anyone that the economic life of the Highlands, particularly in our area, is at a very low level. With the migration into the coal industry, the whole life of certain areas has undergone rapid and radical change. “The machine age has changed their hill virtues into industrial vices,” says Malcolm Ross, and he writes further of the need of training them in trades, health, and the use of their minds for amusement’s sake. (Ross, Machine Age in the HIlls, p.235)

It has often been suggested that it would be helpful to stimulate the mountain people to migrate into other parts of the country. But Mr. Gray cautions against “stimulating the movement of these people to another environment, particularly into the midst of this chaotic industrial world of ours,” and expresses his own faith in the capacity of developing a worthwhile life for the mountain man right in the mountains.

In Harlan County, out of a total of 5,056 between the ages of 14-17, there are 1,895 or nearly two-fifths, who are not in school. This fact is more important when we remember that school ages are high in this section due to late starting and intermittent attendance. In Letcher County, nearly one-third of the same age are not in …

p.4.

school. There are varied reasons — inaccessibility of school; no enforcement of attendance; and the expense of transportation — which must be born by individuals.

Granted that there has been a growth in the number of public schools, primary and secondary, particularly the former, what are they doing to meet the demands created by this rapid social change and what are they doing to help young people meet the demands created by the economics of the mountains? To answer this we must begin at the bottom, and for this purpose let us look at the figures given by Mr. Gaumnitz. He emphasizes the fact that “true education is to be measured by what happens to the child in the classroom — change in habits, knowledge, attitudes, outlook — and the comprehension of the whole scheme of things.” These cannot be measured by figures. But figures do indicate just how much possibility there is for this sort of thing in the light of what we know are necessary prerequisites for good teaching and learning.

| Annual length of school term in days | 143 (in mountain counties) |

| Average days attended per pupil | 96 |

| Percent over age | 52.7 |

| Illiteracy (21 years and over) | 13.3 |

| Percent of teachers with high school education or less | 76.1 |

| Average value of school buildings per teacher | $710.00 |

| Average expenditure per teacher | $610.00 |

| Average salary per teacher | $510.00 |

“In Kentucky, it is found that more than three-fourths of the teachers of mountain counties have the equivalent of a high school education or less. For the non-mountain counties, only 21.3 percent of the teachers are found with so little training.” (Mountain Life and Work, July 1933, p.24)

Frances Lavender Album. Fair Day. Sept. 1918. “Green Cornett, the fiddler from Line Fork, and Bird Turner ‘beating.’ He is the school teacher on Big Laurel.” [lave025.jpg]

From these facts we can draw our own conclusions as to whether or not public education is doing, or could do anything to meet the …

p.5.

needs of the mountain people. Education progresses as people themselves see the need for it. Much of the public education of the mountains is a spill-over from the non-mountain section of the state. It represents the very extreme minimum. Even in less backward sections of the country, public education is far from doing all that could be done. How can we expect to see public education in the mountains fulfilling all the obligations of a good education when the prerequisite of such a condition is a high social standard in the people themselves? The gap between the need for a specialized type of training, and the type of public necessary to demand and instigate such training is greater here than anywhere so that for the time being the inspiration and support of any such thing will of necessity come from the outside. This is the answer to any objection which grows out of the fact that schools like Pine Mountain are supported largely by people outside the state and in other sections of the country. In view of the conditions, the mountain people must have help to get started. Whatever evil accompanies such a venture can be minimized only by making the student realize that such an evil exists, and that of the two evils — going without schools, and having a school supported from the outside — the second is the lesser.

1425 Divide [?] School. [045_VI_FN_pg2a_015.jpg]

As I write this I am interrupted by a caller — a former Pine Mountain student now at Berea. She came from “down Greasy.” Three years ago her brother shot and killed a man, and now we discuss a killing of yesterday when a twenty-year-old boy was killed at a Christmas brawl down the creek. She re-affirms most emphatically the need for Pine Mountain. And just such an incident is the strongest argument we have. For what are the public schools doing about training young people to live at peace with one another? This …

p.6.

is only one of the questions we might ask, and some may say it is the task of the church to answer it, But it is fundamental and far more important than reading and writing. It is one of the places where our public schools in the mountains fail and is just indicative of the fact that they do nothing towards the specialized type of training needed in the mountains. Where practical training for a life situation is needed the children are given abstract abstractions. A different quality is required from what is being given.

Briefly, we may summarize:

- However increased in the past twenty years, there is still an inadequate quantity of public education being offered in the mountain areas.

- The quality is nowhere near adequate. Nothing is being done towards a specialized training for mountain youth to help them cope with the economic and social problems peculiar to the mountains The present public school system is woefully inadequate in physical equipment and personnel.

There is a growing tendency to look critically at a private school in the mountains and rightly so. But the criticism has been directed towards schools whose work overlaps that of public schools, and who offer a semi-classical and academic college preparatory education to children who need practical training in hygiene vocations, etc. Well-intentioned but giving a stone where bread is needed. The only justification for the maintenance of a private school is that it contributes something to the life of the people which is not being done by any other agency; and that the need for such a contribution justifies the money and labor expended.

There is a need for some sort of training place for young people of the mountains, where they may be taught to look critically at …

p.7.

their own problems; where they may be trained in the essentials of leadership; where they may be given opportunity for the specialized training needed for a better life in the mountains, and where they may be given an opportunity for vocational guidance and training in preparation for what we hope will be a brighter industrial era in the hills.

There can be no doubt then for the need of a school which gives a specialized type of training for mountain youth, and one which is flexible in its requirements. As the Danish Folk School has grown up in response to the needs of the people of Denmark, so we must have a distinct type of school of the Southern Highlands. Just “any old kind” of academic training, because it is called SCHOOL will not suffice. Pine Mountain has had a unique history as a pioneer of education in the mountains. This must be continued, but in order to do so we must constantly scrutinize our work in the light of the needs of the mountain people.

GALLERY: Rural Schools and Children Near Pine Mountain Settlement School

- “Alberta Turner teaching Alex Branch School – 1948(?)” Three children and teacher. [nace_II_album_025.jpg]

- “Roy Banks – Bear Branch School 1948.” Children at desks and teacher. [nace_II_album_027.jpg]

- School bus. Series VII-52 Children & Classes. [elem_023.jpg]

Our problem then is — how can Pine Mountain best serve its students and the community? We must confine ourselves for the present to answering the first half of the question since the last half requires a special report. In the consideration of our problem, several interesting questions have arisen, and the problem is made complex by several interesting and important factors.

First, the large turnover of students. From 1914(?) to 1933, 996 students have been at Pine Mountain for a month or more. During that time the average length of tenure for a student was approximately twelve school months. However, since 1931 the turnover has decreased materially. In a study made by Mr. Hubert Hadley, dated March 1931, he shows that up until and including 1931, the average turnover at …

p.8.

Pine Mountain was seventy percent yearly. From 1931 to 1934, the average turnover for the four years has been forty percent, thus showing a marked decrease. Whether or not this is a result of the depression, or from other factors is not known. And whether or not this is a definite trend for the future remains to be seen. On the other hand, while the problem of [the] curriculum is complicated by transient students, the proportion of graduates is steadily growing, and the records show favorably,

It is interesting to note in this connection, that since 1923, thirty-eight students have been graduated from the Senior High School. Of the thirty-eight, twenty-six have been graduated since 1931, and there are fourteen students in the coming graduation class. Of the twenty-six, two are now at home, one is in nurse’s training school, and eight are working, nine are either in college or in Normal School, two are teaching and three are married. These figures indicate that proportionally, Pine Mountain graduates do very well as far as placement after High School is concerned.

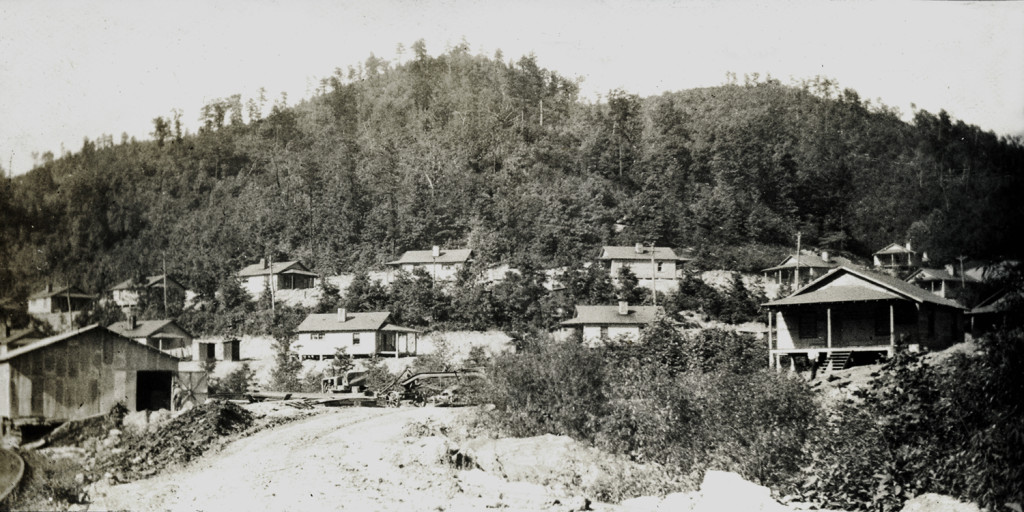

Blue Diamond Mining Camp – Toner, Kentucky. [nace_1_019a.jpg]

Second, the Rural and the Mining Camp children. The Pine Mountain student body is divided sharply into two groups, those who live in a town or mining camp, and those who live in the rural mountain areas. The former group comprises forty-three percent and the latter fifty-seven percent of the student body. While basically the same, and no more than one generation removed from his rural brother the mining camp youth has background differences and an outlook for the future which must be considered. The picture which Malcolm Ross gives in his Machine Age in the Hills is anything but a hopeful one and is quite a contrast to the picture one might draw of those sections of the mountains where the mining camp is absent. The coal industry has reached and passed its hey-day, leaving behind the …

p.9.

wreckage of tremendous industrial deflation in a section unused to industry and totally unprepared to cope with any social problem. It is in fact quite a different social set-up from that found in the rural sections. The youth from the mining camp thinks in terms of the camp store, the tipple, and the motion picture house, and is the product of an unstable and transient community. The rural student returns to a home in the hollow where raising a crop is the major theme. In either case, the average income is low, and vocational possibilities are very few. To limit the school to one group would simplify the problem of curriculum somewhat.

But it seems that the problem of the mining camp youth is at present more astute [acute ?] than that of the rural student. Life in the camp is more complex, and those children reared there have a problem of adjustment which the rural child does not have. In any case, it would seem that our responsibility lies just as strongly in the direction of the camp as the hollow. The mixing of the two groups has a desirable effect when we consider the mountain problem as a whole, especially in this area. To limit the school to one group would tend to make for a group consciousness within the mountain group. The mountain people, both industrial and rural, must learn to think in terms of the whole group.

Third is the question of college, which looms large in the minds of many of the students. The prevailing attitude is that by virtue of a college diploma one is raised from the ranks to a more exalted place. One of the most lucrative occupations in our area, in fact, the only one of much account, is that of a school teacher. This position carries with it considerable prestige and honor. Even an eighth-grade graduate who teachers school is termed “professor”. Consequently …

p.10.

there are many students who are working with this in mind. Prerequisite to college, of course, is the necessary high school “units”. With the student, it is a matter of time and material covered, not a question of attitude, method of finding facts when necessary, general comprehension of things. Education is an abstraction. Consequently, units once received are a closed book.

Fourth is the wide variety of educational levels in one grade. This is inherited as the result of the absence of any kind of academic standardization in the county grade schools, and further reflects the very poor quality which students are receiving. The results of achievement tests given this year illustrate this. It was discovered, for example, that of the twelve students in the seventh grade, nine of whom were new, one was in the eighth-grade level, two in the seventh grade, four in the sixth grade, three in the fifth grade, and two in the fourth. Of the twenty-three tenth grade students, three of whom are new, one was in the eleventh-grade level, four in the tenth, two in the ninth three in the eighth five in the seventh, six in the sixth, and two in the fifth, Of the thirty-two ninth-grade students, twenty-five of whom are new, one was in the tenth-grade level, two in the ninth, four in the eighth, ten in the seventh, eight in the sixth, six in the fifth and one in the fourth. With this wide distribution of educational levels in each grade, one can see what a teacher must face, how difficult is the task of those students who are carrying work far above their educational level, and the retardation in progress which the advanced student must suffer.

And the last consideration is the possibility of student placement. Our only index of what will happen to the student who graduates from Pine Mountain is the record of the thirty-eight who have already …

p.11.

already graduated. It does not seem likely that this good fortune will continue. While the number of graduates was small, the possibilities of placement were good, particularly as a good deal of help was given by individuals interested in Pine Mountain, and in the various individual student. But this is only a temporary arrangement and cannot continue. This year’s class numbers fourteen, and at the present time it does not seem likely that more than three of them will either find work or go to college. Because of the limited number of students which Berea will take, and because of the financial limitations of any who might possibly go to other schools, college is out of the reach of most, even though they might be intellectually qualified. But we cannot escape from feeling a sense of responsibility towards helping those qualified to secure a place where they may use their various talents and training. In other words, we have a definite responsibility towards those graduates who are capable of holding a position if we could secure one for them.

Now we have listed some of the major factors we must keep in mind as we try to make a program for Pine Mountain. In endeavoring to solve our problem of how we can make Pine Mountain most useful to the students we have made the following outline. The order indicates the importance of the items listed, but they cannot be construed as operating as entirely separate from each other.

Girl’s Industrial. Interior view of Co-op Store, c. 1940s. [II_6_swimming_draper_boys_263b.jpg]

- Immediate needs. corrective health, hygiene, methods of cleaning house, sanitation, repair work, farming and gardening, nursing, woodwork.

- Academic adjustment,

- Vocational guidance (which may go hand in hand with 2)

- Liberal cultural education (for want of a better name) Training toward a comprehension of the whole scheme of things.

- Preparation for college for those qualified.

- Out first concern must be for the immediate needs of the boys and girls who come to us. These will naturally vary with the student …

p.12.

student. But in a general way, they will consist of having habits of cleanliness; orderliness; corrective measures in health and hygiene. All students whether they plan to stay one year or six will need these. One of the basic needs of the mountaineer is to learn how to live cleanly and to make the most of his natural surroundings. This, of course, has always been given major emphasis at Pine Mountain. In connection with this, we must keep in mind those basic courses — cooking, sewing, weaving, carpentry and furniture making, farming and gardening, dairying, etc. We must not forget the importance of the general set-up of the school with its requirement that each student does his share of the work necessary for the maintenance of the school. The student benefits more from this one thing than from any other in proportion as there is created in him a sense of responsibility, respect for neatness and orderliness, and cleanliness. All these are virtues whose lack is probably one of the mountain man’s greatest weaknesses. Living at the school is in itself an education. Then as the student becomes adjusted, and the certainty of his continuing in school becomes more assured, special courses in the domestic arts are given.

We feel more and more the need of giving our attention in thought and planning to those students who must return to their homes. Particularly is this true if there is to be no general movement out of the mountains around us here.

Our next concern is in having the student make the necessary academic adjustment. This is often difficult and must be done with considerable care. It is part of what may be called our guidance program. Standard achievement tests, despite their limitations as far as mountain children are concerned, are fairly accurate guides …

p.13.

guides as to the academic standing of a student, and with Intelligence tests, we have a further guide in the proper grade. It cannot always be done and for the most part, we can only approximate it. The wide degree between the student’s academic standing when he comes to us, and actual grade in which he should be enrolled, make an accurate adjustment impossible. This may take several years. In the Junior High school, for the present, we are trying to make each student meet our academic requirements and to take a full-time academic program. This is done for two reasons:

- So that they may learn well the fundamentals, English, Arithmetic, etc.”

- So that we may have time for observation as to their possibilities, aptitudes, etc., for future guidance

In this connection, it is well to say that we are making a definite effort to take as new students those who are ready for the seventh grade, rather than any above. We find it less difficult to remedy habits, and easier to instill the Pine Mountain philosophy into the younger students. Then too, they have a chance to stay here for [a] longer time, thus making our work surer. Furthermore, since the school is committed to a policy which emphasizes industrial training, homemaking, vocations, etc., and makes academic training secondary, the question raised by taking younger children may be overlooked. It is not so much a matter of taking only those children who cannot get to another school as of giving a specialized type of training to any mountain youth.

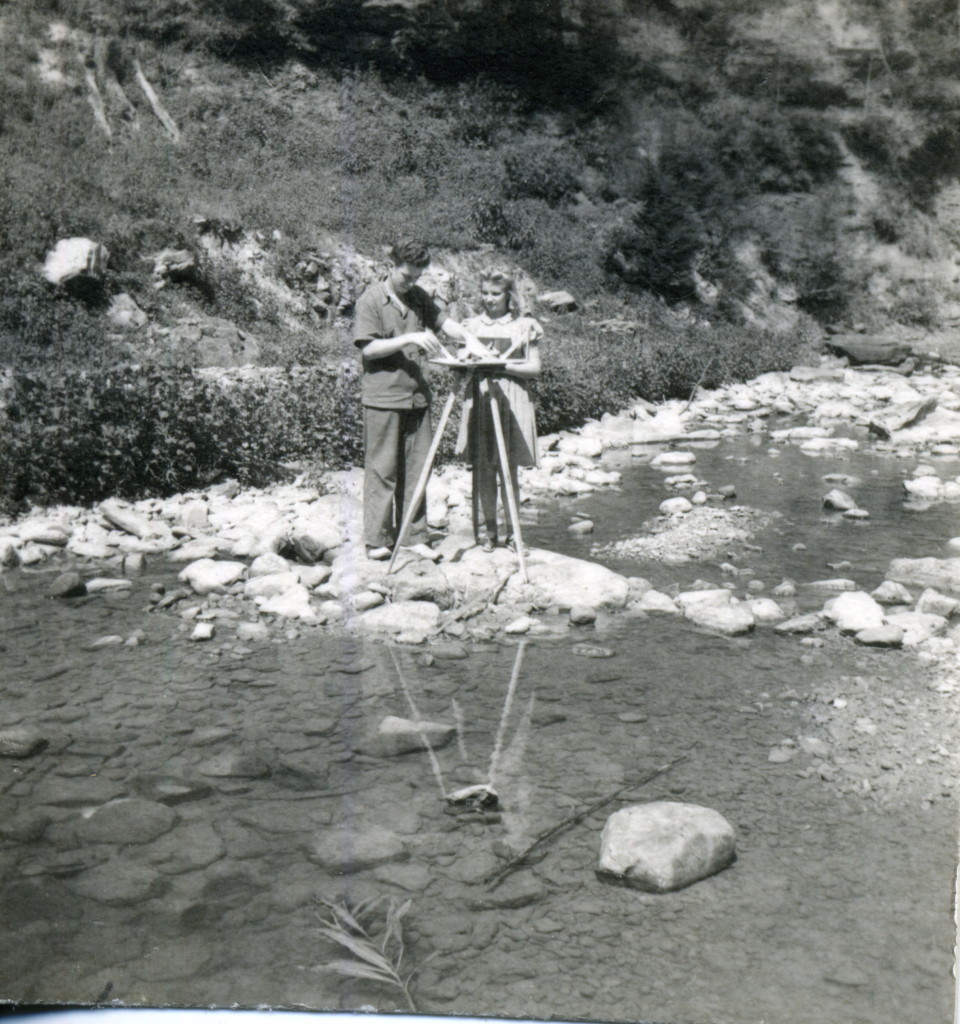

Dieter Album – Ruth Shuler and Jim Bishop learning surveying skills. [shul_013.jpg]

Our next concern has to do with vocational guidance. By this is meant an effort to help the student find out for what he is best suited in the light of his interests, aptitudes, and possible future employment. As yet our own knowledge of the “science” of vocational guidance is very meager. We like to think of our whole plan at Pine …

p.14,

Mountain as one of guidance in the sense which Dr. Brewer [See: John M.Brewer, Education as Guidance, 1932] used the term that all education is, or should be, guidance. But we are trying to find out as much as possible about the student, and in a common sense way trying to help, using our own experience and knowledge, and any other material which can be brought into use. Within our own program, there is quite a bit of opportunity and flexibility to permit a variety of training and experience built around the student himself. To illustrate this let us take several cases here, out of the eighteen who are taking individual courses

“A” is a hardworking, conscientious student; her achievement test shows her to be in the very lowest percentile, and her I.Q. is just below average. Her father and she have college in mind. She has a marked ability in the kitchen where she does her work. After talking the matter over with her she is brought to realize that her marks are low, and though she studies harder than anyone in this class she is getting nowhere. She feels no sense of achievement. She is persuaded as diplomatically as possible to develop her special talent in cooking. Special courses are arranged for her under Miss [Bertha] Cold, the dietitian. Her academic program is cut to English, Business Arithmetic, and some Social Science. The reason for the last will be brought out later in this paper. Most of her time now is spent in the kitchen where she has been given considerable responsibility. She does excellent work, has a real feeling of achievement and is quite happy.

“B” is a hardworking student with about the same academic potentialities as “A”. She displays a real talent for dressmaking. Now she spends most of her time planning and making dresses under supervision, working on projects, and is doing real, advanced work in sewing.

“C” is a boy with a very low I.Q. He is a senior and should be in the seventh grade. He has been promoted each year because he tried, and not because he achieved any academic level. More persistently than anyone else he wishes to go to college so that he may be a school teacher. He has dodged every effort on our part to persuade him to think of some other vocation. All semester the teachers have concertedly brought pressure to bear so that now he has come to realize that the work [of college] is too difficult. He has also been made to realize that woodworking, in which he is proficient, is as honorable a profession as school teaching. The second semester will find him spending most of his time with Mr. Callahan, and perhaps taking a course or two in corrective English and the Social Sciences. He will graduate, but will receive a VOCATIONAL diploma.

p.15.

Eight students are taking special work in the business department. Seven of these are girls who feel that they have a possibility of finding employment after graduation. Several; girls are majoring in weaving. One boy, whose academic work was poor, has a real interest in the dairy. He spends most of his time in connection with this department and is studying Biology, English, and special courses in Dairying. Three boys are majoring in woodworking, and several boys in auto-mechanics. While several boys are working in the print shop we do not have enough room to do much special work in this department.

This illustrates the beginning of our vocational work. As we are physically able it will probably expand three fold in time. But it will require study and planning. It is our present answer to a practical training for our students.

The next point we must keep in mind as we try to meet the needs of mountain youth is the need for a cultural education. Dr. Gaumnitz calls it the “comprehension of the whole scheme of things.” This includes an appreciation of good literature, the ability to read and understand a newspaper; an insight into the truth and continuity of history; a basic understanding of economics; understanding of the Bible, ethics, history of religion; and above all, an understanding of the problems, both social and economic, which are peculiar to the mountains. The last named should play an increasingly important part in our curriculum. The mountain boy and girl must be made conscious of the forces which have been responsible for the retardation of their people. This involves an honest and sincere examination of facts. In the emancipation of the mountain man, he himself must play an active part to make any easier what will be a difficult task.

p. 16.

And finally (with these previous considerations in mind) we must devote our attention to the student who has a fair possibility of getting to college. This will continue until we are on a par with good schools outside the mountains. We shall give two diplomas, one for proficiency in Vocational work, and the other for proficiency in Academic work. We shall gradually tighten our requirements until the student will receive an Academic diploma only when we feel that he is ready for college. This will mean for the time being that there will be fewer Academic than Vocational diplomas given, of course. It may seem to run counter to our avowed effort to make the school practical — this emphasis upon academic standards — but it works to make the school more practical, in that it discourages those who are not qualified in our estimation to go on to college, from attempting to do so. Every allowance will be made for the vocational student as far as classroom work is concerned. We are gradually eliminating grades, except as a part of our own permanent record. We desire the student to forget trades, and work for the joy of learning.

There is one other way, more or less intangible, in which Pine Mountain can render service, and that is by lessening the impact of outside civilization upon that of the mountain people. This can be done by interpretation, and filling in the gap between the extreme rural life of the mountains and the life outside.

GALLERY: Is There Any Further Need of a School Like Pine Mountain Settlement School?

- 01 Is there any further need …1940s_unknown_ed_obligation_001

- 02 Is there any further need … 1940s_unknown_ed_obligation_002

- 03 Is there any further need … 1940s_unknown_ed_obligation_003

- 04 Is there any further need … 1940s_unknown_ed_obligation_004

- 05 Is there any further need … 1940s_unknown_ed_obligation_005

- 06 Is there any further need … 1940s_unknown_ed_obligation_006

- 07 Is there any further need … 1940s_unknown_ed_obligation_007

- 08 Is there any further need … 1940s_unknown_ed_obligation_008

- 09 Is there any further need … 1940s_unknown_ed_obligation_009

- 10 Is there any further need … 1940s_unknown_ed_obligation_010

- 11 Is there any further need … 1940s_unknown_ed_obligation_011

- 12 Is there any further need … 1940s_unknown_ed_obligation_012

- 13 Is there any further need … 1940s_unknown_ed_obligation_013

- 14 Is there any further need … 1940s_unknown_ed_obligation_014

- 15 Is there any further need … 1940s_unknown_ed_obligation_015

- 16 Is there any further need … 1940s_unknown_ed_obligation_016

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Brewer, John M. Education as Guidance. New York: Macmillan Co.. 1932.

Gaumintz, Walter H. For an extensive bibliography of Gaumintz’s work in education see: http://onlinebooks.library.upenn.edu/webbin/book/lookupname?key=Gaumnitz%2C%20Walter%20H%2E%20%28Walter%20Herbert%29%2C%201891-

Gaumnitz, Walter H., ” Extent and Nature of Public Education in the Mountains,” Mountain Life and Work (Conference Proceedings) — Vol 09, n.2 July 1933. p.20 —

Gray, L.C. “Economic Conditions and Tendencies In the Southern Appalachians As Indicated By the Cooperative Survey,” Mountain Life and Work (Conference Proceedings)., Vol 09, n.2 July 1933. p.6 —

Ross, Malcolm. Machine Age In the Hills, New York: The Macmillan Company, 1933.

Malcolm Ross, the author of Machine Age in the Hills, produced very few books and those few give us pause as their topics are far a-field from the keen economic and sociological observations found in Machine Age In the Hills. The strangest of his topics is a science fiction work, The Man Who Lived Backward, (1950). Another title is his autobiography, The Death of a Yale Man, (1939), a more favorably received work that covers the years of the New Deal.

Spears, Harold. The Emerging High-School Curriculum and Its Direction. New York: American Book Company, 1940. See: “Meeting Needs at Pine Mountain,” pp. 73-93.

Wilson, Everett K. A Pine Mountain Study in Civics, Pine Mountain Press, 1937

Morris, Glyn. Less Traveled Roads, New York: Vantage Press, 1977.

Return To:

GLYN MORRIS Director

GLYN MORRIS Guide

GLYN MORRIS 1931-1977 Guide to Talks, Writing, and Publications