Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 09: BIOGRAPHY – Staff (Mary Rockwell Hook)

Series 24: PUBLICATIONS RELATED

Victory Gardens

1942

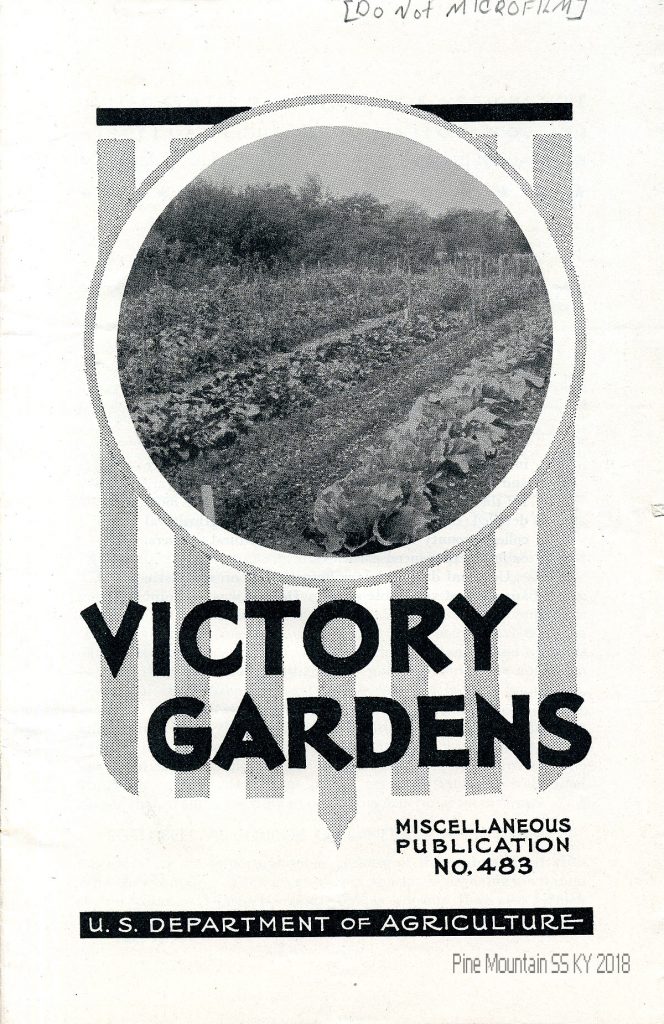

“Victory Gardens.” Cover of USDA publication. [usda_victory_gardens_cover.jpg]

TAGS: Publications related to Pine Mountain Settlement School, Victory Gardens, WWII, farming, gardens, United States Department of Agriculture, USDA, Grow Appalachia, rural gardening, cabbages, beans, sustainable agriculture, Leon Deschamps, May Ritchie, George Willis Pack, Charles Lathrop Pack

PUBLICATIONS RELATED Victory Gardens, 1942

This publication, found in the correspondence of Mary Rockwell Hook, Master Architect for Pine Mountain Settlement School, describes a popular WWII movement that was already a familiar practice to families in Appalachia.

CHARLES WILLIS PACK AND THE VICTORY GARDEN IDEA

The idea of Victory Gardens played a significant role in the education of those who attended Pine Mountain Settlement School during both WWI and WWII. The formal history of Victory Gardens had its origins in Appalachia in the person of George Willis Pack, one of the most noteworthy citizens of Asheville, North Carolina, in the latter half of the nineteenth century. While George W. Pack was a somewhat rapacious lumberman, he gave birth to a very conscientious son, Charles Lathrop Pack, who then gave us a very powerful statement on what it means to grow a “Victory Garden.”

Charles Lathrop Pack, like Katherine Pettit, was inspired by the Country Life Movement and also by the City Beautiful Movement, — both popular movements that near the turn of the century tried to address the growing blight that was fast destroying both the countryside as well as cities across the country. When WWI came along both of these movements were threatened and additionally, food shortages became even more threatening. Charles Pack brought forward the idea of the “victory garden.” In March 1917, he organized the US National War Garden Commission and launched the war garden campaign. Pack planted the seed, but history saved the seed. We continue to harvest the ideas that Pack first put forward, the idea of joining gardens with civic and civil responsibility.

PACK’S INFLUENCE ON PMSS

It is not surprising to find a copy of “Victory Gardens,” the USDA pamphlet in the Pine Mountain Settlement School architect Mary Rockwell Hook’s papers. Born in 1877, Hook, like Pack, was inspired by the World Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 which attracted many of the country’s leading architects and landscape artists including George Kessler, John Nolan (who developed the 1921 Asheville Plan), Frederick Law Olmsted (who designed for the Exposition), Calvert Vaux, Charles Mulford Robinson, and Daniel Burnham. Like Charles Pack, Olmsted, Nolan and others, Hook believed that beautiful places could attract business and commerce and she knew farms and garden first-hand —- so to speak.

When Charles Pack took the City Beautiful Movement one more step forward, he believed that beautiful places could also be innovative and produce healthy commodities for the growing threat to the U.S. food supply during wartime. He quickly added his initiative to the WWII war efforts.

He wrote

“Every city aims to be as prosperous and progressive as possible and nowadays most people realize that the city beautiful is also likely to be the city commercially worthwhile. Probably no other one enterprise will add more to a city’s beauty than gardening. Gardening, therefore, has double value. It both enriches and beautifies. By the same token, it develops civic pride and community spirit.

For these reasons, any community should delight in being called a “garden city,” whether the name is applied literally or merely in a figurative sense. One result of the war-garden movement is that practically any American community can truthfully be designated by this term.

It is fortunate indeed that this is true. Unity of thought, of action, of ideals, is the crying need of the hour in America. United, we stand; divided, we fall. Probably nothing is more potent as a factor for building up community spirit than gardening, particularly community gardening. A link to bind men together is gardening. It creates common interests. It unites all hands in the common end of producing food. Rubbing elbows in their garden patches, lawyers and laborers, tradesmen and housewives, speedily discover that they have much in common. One of the things they have in common is their interest in their community; for each wishes to see it progress.” [The War Garden Victorious by Charles Lathrop Pack, Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, illust. 1919]

This same vision must have been in the mind’s eye of Katherine Pettit and Mary Rockwell Hook, Marguerite Butler, Ethel de Long, and others when they were imagining Pine Mountain Settlement School’s future, for the same messages permeate the literature of these women.

Throughout the country, Victory Garden posters began to appear and the public began to respond. “Plant a Victory Garden” began to appear in various forms on city walls and in magazines and newspapers. The posters were eye-catching and a rallying cry for the War effort. The common goals of the gardens built community cohesion and raised community pride. [For more information, search resources on the National Archives website, such as “Sow the Seeds of Victory! Posters…World War I.“)

During WWI Pine Mountain could not have managed the food requirements of the settlement school without their “Victory” garden. Whether 10,000 cabbages, or 200 bushels of beans, or 100 cabbages and 1 bushel of beans, the garden could mean the difference between starvation and “making it” in lean times in Appalachia. Now, the whole country was feeling the pinch. At Pine Mountain, everyone contributed time to the garden. During WWII when so many of the young men at the School left to fight for the War, women and children carried on the duties of the garden.

In WWII the farmer and some staff at Pine Mountain Settlement were “exempt” from recruitment because their work was deemed essential to maintain the homeland. Farm, dairy, and garden workers were evaluated by points and this included, for example, cows, as each cow counted as one point during the War. Pine Mountain did very well with approximately 18 cows which needed to be maintained at the start of the war and this exempted both lead farmers, William Hayes and Brit Wilder.

POST-WWII GARDENING

When the Victory Garden idea began to wane and the population again became comfortable with the local market as a supplier, family and community gardens still dotted the landscape. While Charles Lathrop Pack was given credit for initiating the Victory Garden and his book The War Garden Victorious (1918) captured the imagination of the country during WWI, the idea hung on in the minds of many. As gardens sprang up across the landscape of both city and country, it became clear that environmentalists held ideas in common with the Victory Garden, but then so had Charles Lathrop Pack. He saw the ideas as inseparable and his Memorial Tree Movement following the war was uniquely his own idea of the merger of the two ideas. Under Pack’s guidance the idea grew from the need to provide “some fitting memorial to soldiers who had served in WWI” to a strong civic and environmental movement.

Pack was well situated in Asheville to see the devastation that improper forest removal could bring to an area. His father had come to the city as a lumberman and made his fortune from the surrounding forests. However, Asheville was also the home of the nearby Cradle of Forestry which worked with the Yale Foresty program to train the country’s first foresters. Today, it continues to celebrate the creation of a forestry consciousness and has led many young men and women into the field of forestry. These first degree programs in the science of forest management were in many ways responsible for saving vast tracts of national forest in the Appalachian mountains and for inspiring Charles Latrop Pack and others.

LEON DESCHAMPS AT PMSS

Leon Deschamps, a Belgian who fought in WWI, was trained in Europe as a forester and became the forester and the farmer for Pine Mountain in its very earliest years. His love of the Kentucky mountains was only matched by his love of a Kentucky girl. His marriage to May Ritchie, of Viper, Kentucky, (the oldest daughter of the “Singing Family of the Cumberlands”) was a celebration long remembered in the region and in the School’s history.

Deschamps while at Pine Mountain, created “The Perfect Acre” a kind of forest -garden which he located behind the school’s Chapel, as both a memorial and an acknowledgment of the spiritual and healing power of the forest garden. It was May Ritchie’s famous sister Jean Ritchie who later sang about the joys of the garden in “The Cool of the Day. [AUDIO]”

PACK’S MEMORIAL TREES PROJECT

Pack’s efforts and interests also led him to another publication, Trees As Good Citizens, published in Washington, D. C., by the American Tree Association (1922). it speaks to the community building potential of trees and forests.

It was while President of the American Forestry Association in Washington, D.C., that Charles prepared a small booklet called “Memorial Trees,” in which he lauds the memorial tree. He says to his audience

“If you or your city have not joined the army of those who are planting Memorial Trees, enlist now! … It is one of the most important pieces of reconstruction work in the United States.

The idea for the Memorial Tree movement grew out of the need to provide some fitting memorial to soldiers who had served in WWI. The movement also extended to Europe where the devastation to the forests in Belgium, Great Britain, and Italy are well known. The forest authorities in a number of European countries worked with Pack and with the American Forestry Association to send saplings and seed to Europe to begin the re-planting process.”

Thomas R. Marshall, Woodrow Wilson’s vice president, said of the Memorial Trees program

“The idea appeals to me far more than storied urn or animated bust. It embodies a living thing, representative of a vital sentiment of the American people and I hope it is going to be universally popular in America.”

It is not surprising to see this idea resurrected in the Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative [ARRI] that seeks to find ways to heal the visual and emotional scars of the rapid destruction of mountains and trees in surface mining operations in the Southern Appalachians. Beginning in the late 1960s the mining method destroyed vast tracts of forest, removed mountain tops, and created inhospitable soil for forest rejuvenation. Still active today, ARRI has planted millions of trees, but they cover only a fraction of the ongoing destruction of mountains and gardens in the Southern Appalachians.

While the story of Charles Lathrop Pack and his father are part of an important history of the urban South and are well-known in many circles, the stories of gardening in the more remote rural areas of Appalachia such as Pine Mountain Settlement School have seen less attention. Yet, very early, many in the rural South were experimenting with and creating remarkably advanced gardening programs in schools such as those found in the settlement school milieu.

URBAN AND RURAL GARDENING TODAY

Today, the idea of “farm to table” joins other catchphrases such as “slow food” as more urban areas remind us how much urban life misses by not being a party to the creation of their healthy food sources.

Movements that seek to bring fresh produce to the American table in both urban and rural homes are now thriving and backyard gardens are on the increase in urban settings. Today, considerable creative and innovative gardening is also being carried forward in very rural communities, particularly those connected to the “Grow Appalachia” movement. This grass-roots initiative is making great strides in improving the diets of Appalachians in both town and country.

Charles Lathrop and Katherine Pettit would both be cheering if they stood next to many of the small gardens now growing in the backyards, along the creeks, and on the steep slopes of Appalachia — gardens that are moving families toward healthy eating. In rural Appalachia and particularly in the Pine Mountain valley and hollows, the garden is again a testament to the victory of human ingenuity, industry and also memory.

See Also: George Willis Pack: A Name That Will Endure, for a link to a special exhibit that celebrated Pack Square in Asheville, N.C. prepared by Helen Wykle, staff, and students at the University of North Carolina at Asheville in August 2006.

GALLERY: PUBLICATIONS RELATED Victory Gardens

- “Victory Gardens.” Cover of USDA publication. usda_victory_gardens_cover

- p. 00 Victory Gardens usda_victory_gardens_intro

- p.1 Victory Gardens usda_victory_gardens_001

- p. 2 Victory Gardens usda_victory_gardens_002

- p. 3 Victory Gardens usda_victory_gardens_003

- p. 4 Victory Gardens usda_victory_gardens_004

- p .5 Victory Gardens usda_victory_gardens_005

- p. 6 usda_victory_gardens_006

- p. 7 usda_victory_gardens_007

- p. 8 usda_victory_gardens_008

- p. 9 Victory Gardens usda_victory_gardens_009

- p. 10 Victory Gardens usda_victory_gardens_010

- p. 11 Victory Gardens usda_victory_gardens_011

See Also:

FARM AND FARMING

FARM AND FARMING GUIDE

MARY ROCKWELL HOOK Architect – Biography