Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 09: BIOGRAPHY

William Hayes, Student (1934-1938),

Farm Manager (1937-1953),

Trustee (1980s & 1990s)

Putney Ranger Station. [putney_views_003.jpg]

TAGS: William Hayes (Part II), William Hayes, Bill Hayes, Fern Hall Hayes, farm manager, Dr. Richard Drake, Berea College Service Award, surface mining, strip mining, SMCRA, Kentucky Division of Forestry, US Forest Service, Daniel Boone National Forest, Red River Gorge, Little Shepherd Trail, forestry, Wilson Wyatt, Kentucky Department of Natural Resources, Gene Butcher, H.W. Berckman, William Music, H.B. Newland, Office of Surface Mining US Department of the Interior, mining reclamation, Lands Unsuitable for Mining, Tom Gish, coal mining, coal camps, tuberculosis, Dr. Willis Weatherford, Howard Burdine, Patrick Angel

WILLIAM HAYES (Part 2)

Student, September 1934 – May 1938

Farm Manager, 1937 – 1953

Member, PMSS Board of Trustees, 1980s & 1990s

Kentucky Division of Forestry, Putney, KY

When William Hayes (1917 – 2006) resigned from his position at Pine Mountain Settlement School on August 1st, 1955, he did not move far from the School. He took a job as the forester (Fire Control Assistant) with the Department of Conservation, Division of Forestry, Kentenia Unit, Putney, Kentucky. The unit was located eight miles across the steep Pine Mountain from the Settlement School. As a forester, Bill continued one of his passions, looking out for the region’s trees and forests.

Putney is part of the New Deal history of Eastern Kentucky. The Kentenia Forest surrounding the Putney Ranger Station was the first state forest in Kentucky. Established in 1919 on the South side of Pine Mountain along the Cumberland River in Harlan County, the name Kentenia was derived from the Kentenia-Cantron Corporation a timbering corporation that had logged heavily in the area. The company made the initial gift of land to the state of Kentucky in a series of disparate tracts that totaled some 3,624 acres of land. [See: http://www.forestry.ky.gov/programs/stateforest/State+Forest+Locations.htm]

[See: http://www.forestry.ky.gov/programs/stateforest/State+Forest+Locations.htm]

The Ranger Station was first a CCC Camp [Camp S-53], one of several created in Eastern Kentucky and later permanent buildings were erected by the CCC, Company 512 on the site. The original site plan called for a large 69 x 49-foot dwelling to serve as the office and home of the ranger. In addition, there were five out-building and a large reservoir for water supply. See the 2005 Kentucky Heritage Council report that details the construction and site of the Station.

In 1961 the forests of Kentucky were owned by some 243,488 people. Of this number, some 99 out of every 100 owners had holdings of less than 500 acres each. This statistic points to the fact that almost 80% of the total forests in Kentucky at that time were in small personal ownership. [The Back Fence, Kentucky Division of Forestry, Issue N.2, February 1961.] These were the forests of southeastern Kentucky that the Division of Forestry was charged to protect and preserve under Bill’s guidance. As part of the forestry program. Bill was charged to prepare daily fire records, and individual fire reports, supervise personnel, and report out to the U.S. Weather Office during fire season. He also supervised the dispatcher who was on duty during fire seasons. The dispatcher was Fern Hall Hayes who was also his support in maintaining community outreach for programs and preparing news items related to fire safety and prevention.

Putney Tower in the Kentenia Sate Forest, c. 1963. [hayes_2015_019_mod.jpg]

An important part of the forestry program and one mandated by many districts in the State was the selling of seedlings to farm operators, doctors, lawyers, teachers, and others. These “Johnny Appleseeds” or, tree seeds and saplings were taken very seriously by Bill’s unit and his dedication to growing Kentucky’s forests was particularly remarkable in the Southeastern district. Bill Hayes did not need convincing that trees were important and when the tree sales were tabulated for the state, the Southeastern District had sold 883,000 seedlings, second only to the Eastern District which sold 962,000. Comparatively, and understandably, the Blue Grass District sold only 77,000 trees. [The Back Fence, Kentucky Division of Forestry, Issue N.2, February 1961.]

In an article in the Harlan Daily Enterprise of March 27, 1960, “Forester has Many Winter Duties,” a description of some of the duties of Bill and his wife Fern is described. They included a seedling distribution program, speaking to schools, garden clubs, civic groups, and farmers; repair of equipment used in fire suppression; weather observation; tracking the “burn index” of the area; mapping locations of fires; reports and dispatches of daily fire dangers, and more.

Putney Ranger Station, west facade, c. 2011. Photo: P.D. Christian. [hayes_putney_pd_01.jpg]

The home and office, constructed of massive logs and finished in its interior with chestnut paneling and walnut, were seated on a foundation of local sandstone. The masonry was crafted by Italian stone masons who had been hired to train the CCC builders. The Italians were often hired by local mining companies to complete commissaries, schools, and churches for larger mining companies like Benham and Lynch in Harlan County. The nearby large stone reservoir that supplies the water for the Forestry Station, is particularly well crafted. Also, an artesian well supplied excellent water until the water table dropped in later years. A supply and maintenance building, a two-story workshop and a large garage shared the premises.

GALLERY I: Putney Ranger Station

- William Hayes. Forestry float, c. 1960

- William Hayes with colleagues at Putney Ranger Station, living room. c. 1960 [hay0146]

- Putney Ranger Station: William Hayes, Elmore Grim, Wilson Wyatt, Lt. Gov. ? , Marcum. [hay0145]

- William Hayes. Forestry meeting at Putney Forestry Station, c. 1963. [hay0144]

- Putney Ranger Station: William Hayes, Elmore Grim, Wilson Wyatt, Lt. Gov. ? ,Maynard Marcum. [hay0143]

- William Hayes. with KY Forestry staff at Putney, KY. [hay0142] ]c.1960_fam_pmss_1944_035

- Putney Ranger Station seen from the front. [putney_distant_view.jpg]

- Putney Ranger Station seen from East flank.

- Putney Ranger Station front door with flag-stone terrace.

When Bill and Fern moved into the job, the main structure was in some disrepair and they immediately began restoration of the building by refinishing the floors, removing years of dark linseed oil from the chestnut paneling and re-chinking logs throughout the structure. The restoration of buildings and grounds continued during the ten years they were at the unit headquarters. New plantings around the buildings, new cabinets, window repair, and other conservation efforts continued during their occupancy.

In assuming the new position, Bill replaced William Music as the lead forester for Harlan County. Bill’s position, he was under the supervision of Wallace L. Disney the District Forester in Pineville, Kentucky and H.W. Berckman, Assistant Director and H.B. Newland, Director of the Kentucky Department of Conservation Division of Forestry. When Bill resigned his position at Putney in August of 1965, Gene L. Butcher was acting Director of the Division of Forestry for the State.

[See: http://www.heritage.ky.gov/NR/rdonlyres/F142A86E-19C0-4FFD-8097-09474F37C9EF/0/NewDealBuilds.pdf]

WILLIAM HAYES (Part 2): LITTLE SHEPHERD TRAIL

Goat wandering on the Little Shepherd Trail. Photo: Environmental education class – St. Francis School

A remarkable part of Bill’s Putney years was the creation of a unique transportation corridor on the top of Pine Mountain. Originally a rough fire break, an improved road along the fire break and an extension of the road came to be called the Little Shepherd Trail. Bill played a significant role in its creation.

On December 23, 1958, Bill wrote a letter to Cam Smith, the County Judge for Harlan County, regarding road funding that was proposed for Harlan County. It was the beginning of a dialog that would result in the eventual construction and reconstruction of a small road along the crest of Pine Mountain. This road was later to be named the Little Shepherd Trail, after John Fox Jr.’s popular book, The Little Shepherd of Kingdom Come, set in the area.

In his plea for assistance in developing what was then only a trail, Bill provided a two-page justification for the use of county money to fund the road. In the Letter to Cam Smith, he notes:

..[I] wish only to speak from my own personal observations of the rural roads which I feel could help the work situation as well as open up recreation areas and provide easy access to some of our timber boundaries ….

Bill believed the road would facilitate the monitoring and fighting of seasonal forest fires, but would also serve the public with “…turnouts for picnic spots and the like ….” And, stretching his vision even further, he noted that

With very little work a rough trail could be graded out from 421 highway to Camp Blanton and on to Gross Knob Lookout Tower, along the top of Pine Mountain and off by way of the Gross Knob Truck Trail. This would make a nice Sunday afternoon drive for our people as well as tourists.

On June 25, 1965, The Courier-Journal Magazine described the visit of Lieutenant Governor Wilson Wyatt to Putney and Pine Mountain for the dedication of the Little Shepherd Trail. From the School, the Lieutenant Governor traveled to the top of the Pine Mountain ridge just above Pine Mountain School where he turned the first shovel of dirt for the road that Bill proposed in 1958. After breaking ground, the Lieutenant Governor told the assembled group that the road held great promise, but that funding was not yet available. Wyatt and his agencies envisioned a 38-mile-long rustic skyline drive but did not reveal a plan on how they would fund such a vision.

It was a “hang your clothes on a hickory limb, but don’t go near the water” scenario; a fiduciary shell game that finally settled on initial funding through the Kentucky Division of Forestry. While it was a road that held promise for later more robust funding and refinement, the project saw little funding support over its many years.

The author of the Courier-Journal article, Joe Creason, noted that some 6 miles of the road had already been partially prepared by Bill’s unit to a width of 12 feet and that the expenditure was just over $400, “a ridiculously low cost. ” Creason described the early road

The result is not a speedway. Instead, it is a rustic, slow-cadence, traffic-worthy trail that opens up perhaps the widest sweep of unspoiled mountain vistas in Kentucky.

Little Shepherd Trail, view 2012. Photo: H. Wykle. [2012-05-13 02.49.15.jpg]

Today the “skyline” drive of Wyatt stretches along 38 miles up and down dip-slopes, passing by Table Rock Overlook, Hurricane Gap, Copperhead Gulch, by Kingdom Come State Park and Raven’s Rock and on to Scuttlehole Gap. Today, it doesn’t continue to open up “the widest sweep of unspoiled mountain vistas.” Instead, it offers intermittent views of Bill’s “aggravation” through the forest curtain. From Baxter almost to Whitesburg it affords intermittent views of the devouring surface mining operations that continue to scar nearby mountains. The fight to save not just trees, but mountains, was to become Bill’s last career.

WILLIAM HAYES (Part II): Kentucky Guild of Artists and Craftsmen

During Bill’s ten years with the Kentucky Division of Forestry, he was also actively engaged in early Kentucky craft activities — specifically the fledgling Kentucky Guild of Artists and Craftsmen.

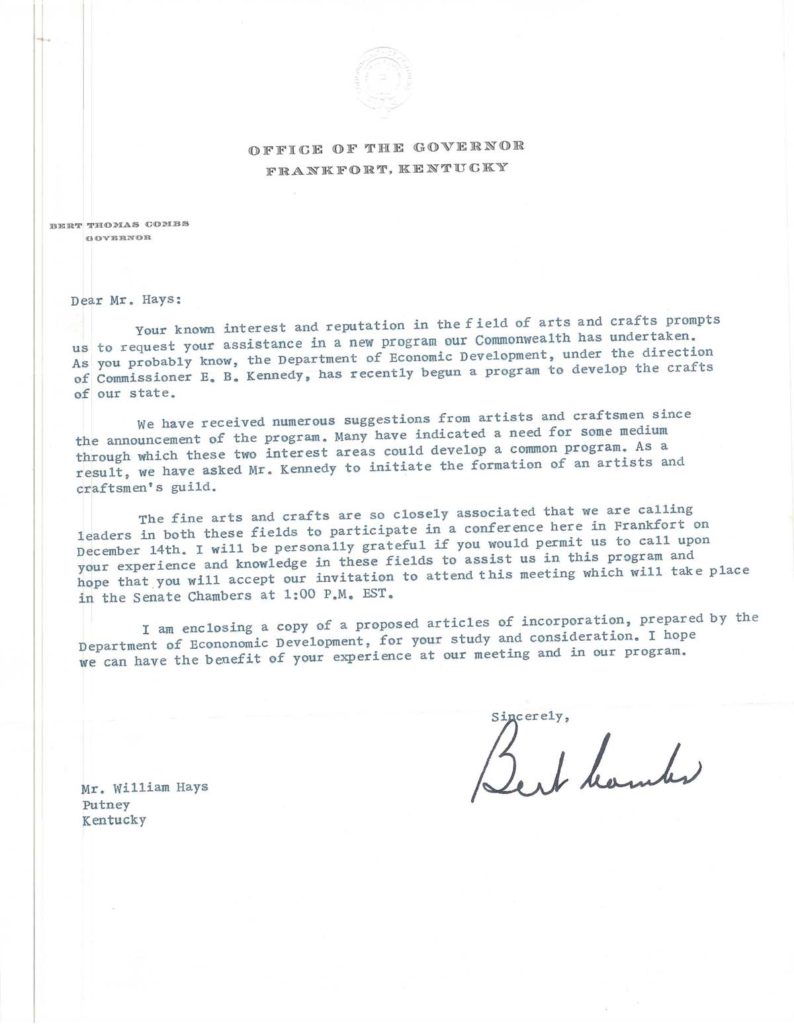

The Kentucky Guild of Artists and Craftsmen was established In December of 1960 on the orders of Governor Bert Combs through the Department of Economic Development and under the direction of Commissioner E.B. Kennedy. The new program under Mr. Kennedy was charged to develop the crafts of the State of Kentucky. To that task Mr. Kennedy called together those with knowledge and interest in Kentucky crafts to the Senate Chambers of the Capitol in Frankfort on December 14, 1960, to discuss the possibilities. At that time the proposed Articles of Incorporation, prepared by the Kentucky Department of Economic Development were presented for consideration. Bill was invited to this planning session.

Always interested in arts and crafts, Bill continued his exploration of craft forms when he left Pine Mountain. He had been exposed to the skills of some of the finest wood crafters at the School such as Boone Callahan, Bennet Hall and later, Frank “Unk” Cheney. (The work of all three may still be seen at the School.) As Bill continued to work with wood and with the forests of the State, he noted wood’s potential as a craft industry and continued his personal work on furniture pieces and other large craft projects. His interest in craft and the potential for a craft industry caught the attention of a newly formed Kentucky craft organization, and on the invitation of the governing board and the Governor of Kentucky he was invited to the first organizational meeting of the Kentucky Guild of Artists and Craftsmen in Frankfort in 1961. During the early years of the organization, Bill was invited to participate in planning meetings of the Guild to contribute ideas regarding the use of wood products from Kentucky’s eastern forests in the Guild craft programs. He was one of the founding members of the organization.

During the early years of the organization, Bill was invited to participate in planning meetings of the Guild to contribute ideas regarding the use of wood products from Kentucky’s eastern forests in the Guild craft programs. He was one of the founding members of the organization.

Bert Combs, acknowledging Bill’s interest and commitment to the use of wood products sent the following letter:

Dear Mr. Hayes,

Your known interest and reputation in the field of arts and crafts prompts us to request your assistance in a new program our Commonwealth has undertaken. As you probably know, the Department of Economic Development, under the direction of Commissioner E.B. Kennedy, has recently begun a program to develop the crafts of our state.

We have received numerous suggestions from artists and craftsmen since the announcement of the program. Many have indicated a need for some medium through which these two interest areas could develop a common program. As a result, we have asked Mr. Kennedy to initiate the formation of an artists and craftsmen’s guild.

The fine arts and crafts are so closely associated that we are calling leaders in both these fields to participate in a conference here in Frankfort on December 14th. I will be personally grateful if you would permit us to call upon your experience and knowledge to these fields to assist us in this program and hope that you will accept our invitation to attend this meeting which will take place in the Senate Chambers at 1:00 P.M. EST.

I am enclosing a copy of a proposed articles of incorporation, prepared by the Department of Economic Development, for your study and consideration. I hope we can have the benefit of your experience at our meeting and in our program.

Sincerely,

Bert Combs

WILLIAM HAYES (Part II): Woodworking

Bill’s woodwork is represented in many offices and homes including state offices in Frankfort wh ere he was commissioned to build book cases for the Office of the Kentucky Department of Natural Resources and a speaker’s gavel for government meetings and several fireside stools for Presidents of Berea College. He continued his woodworking endeavors until his mid-80s.

ere he was commissioned to build book cases for the Office of the Kentucky Department of Natural Resources and a speaker’s gavel for government meetings and several fireside stools for Presidents of Berea College. He continued his woodworking endeavors until his mid-80s.

Always committed to a style that derived from the finest craft at Pine Mountain, his furniture often emulated styles of Boone Callahan, Frank “Unk” Cheney, and others. As a contributor to the Kentucky Guild of Artists and Craftsmen, he produced a large number of so-called fireside stools from a variety of wood taken from the forest of his home in Viper. The salvage of an ancient chestnut tree, worm-holes and all, was used, as well as walnut, butternut, maple, oak, poplar, cherry and mulberry.

WILLIAM HAYES (Part II): US Forestry, Red River Gorge & Daniel Boone National Forest

Before Bill moved on to Surface Mining Reclamation, he transferred from the Kentucky State Division of Forestry position in 1965 to an interim position with the US Forest Service out of the Pineville office. The Federal position provided him another perspective on the status of public lands and parks in Kentucky and the encroaching dangers that were hewing and chewing away at the edges of some of the state’s most pristine land and forests.

One of these locations was the Daniel Boone National Forest. Originally called the Cumberland National Forest when it was created on February 23, 1937, by Franklin D. Roosevelt, a name-change was pushed forward in the 1960s and it officially became known as the Daniel Boone National Forest on April 11, 1966. With the exception of a tract known as the Red Bird tract, the boundaries of the Cumberland map easily mapped to the new Daniel Boone National Forest and provided recreation for some 16 counties.

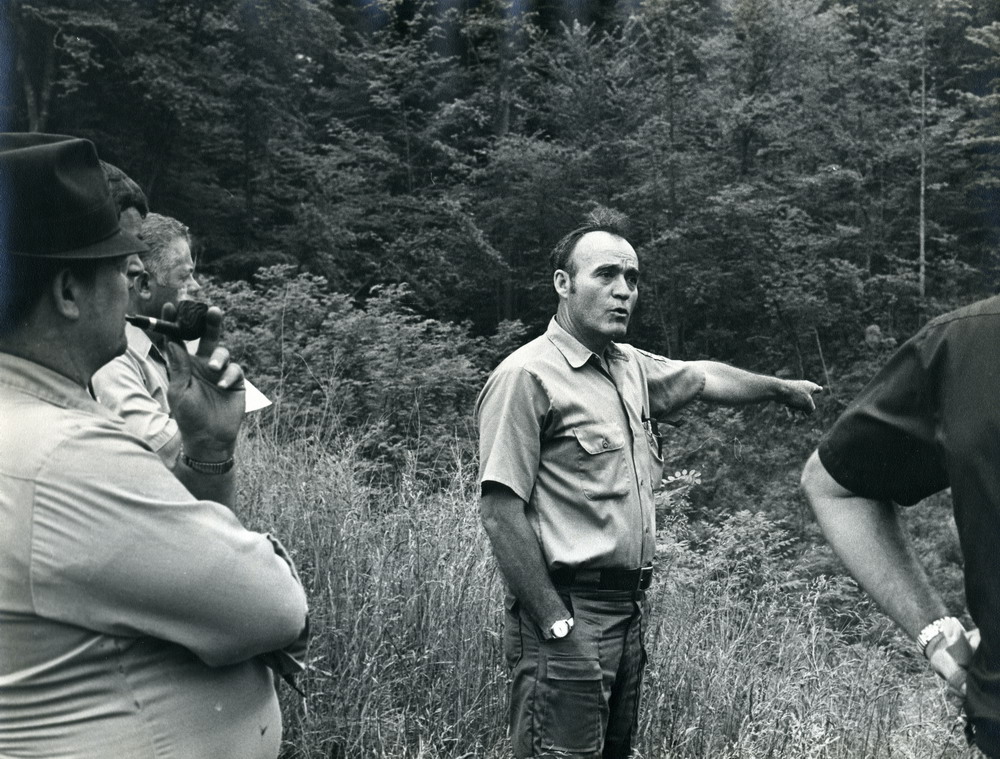

One very significant tract was added during Bill’s tenure, This was a particularly pristine area known as the Gladie tract which became a central section of the so-called Red River Gorge area, a 15-mile tract that is bordered by towering cliffs of limestone some 600 feet tall. When a dam was proposed on the Gorge in the early 1960s, opposition quickly grew, and by April of 1969 the forces of opposition to the dam had made their case and the dam plans were axed, saving one of Kentucky’s most beautiful wilderness areas from destruction. It was one of the first Corps of Engineers dams to be stopped for environmental reasons, in the U.S,. This was the area where Bill was privileged to monitor and lead nature walks. Here he explored and explained some 50 species of mammals, 275 bird species, and numerous rare species of flora. This beginning instructional task, leading nature walks and sharing the forest, was one of his more pleasant jobs with the US Forest Service. The aggravation came later.

Though his time with the US Forest Service was short, it was, again, a leap in education and interest for him. His area of work also encompassed the Cumberland Gap National Park area as well as the rapidly developing Red River Gorge area. While taking nature walks with visitors and patrolling the various park areas, Bill came up against one of the greatest threats to the natural beauty of the area, the renegade park user. This destructive user grew in to the larger part of his job. Soon his job became largely one of law enforcement and not one of edification. Though, it is not hard to believe that most of those errant parkgoers went away strongly edified after encountering Bill. No doubt, the small number that were intent on disruption, were also strongly edified when counseled by Bill. Soon, what he had hoped would be a joy, became a series of contentious encounters with a public intent on disrupting the communion with nature. This encounter was practice for what was to follow.

WILLIAM HAYES (Part II): KY Dept of Natural Resources – Badge #1 Strip Mine Reclamation Officer

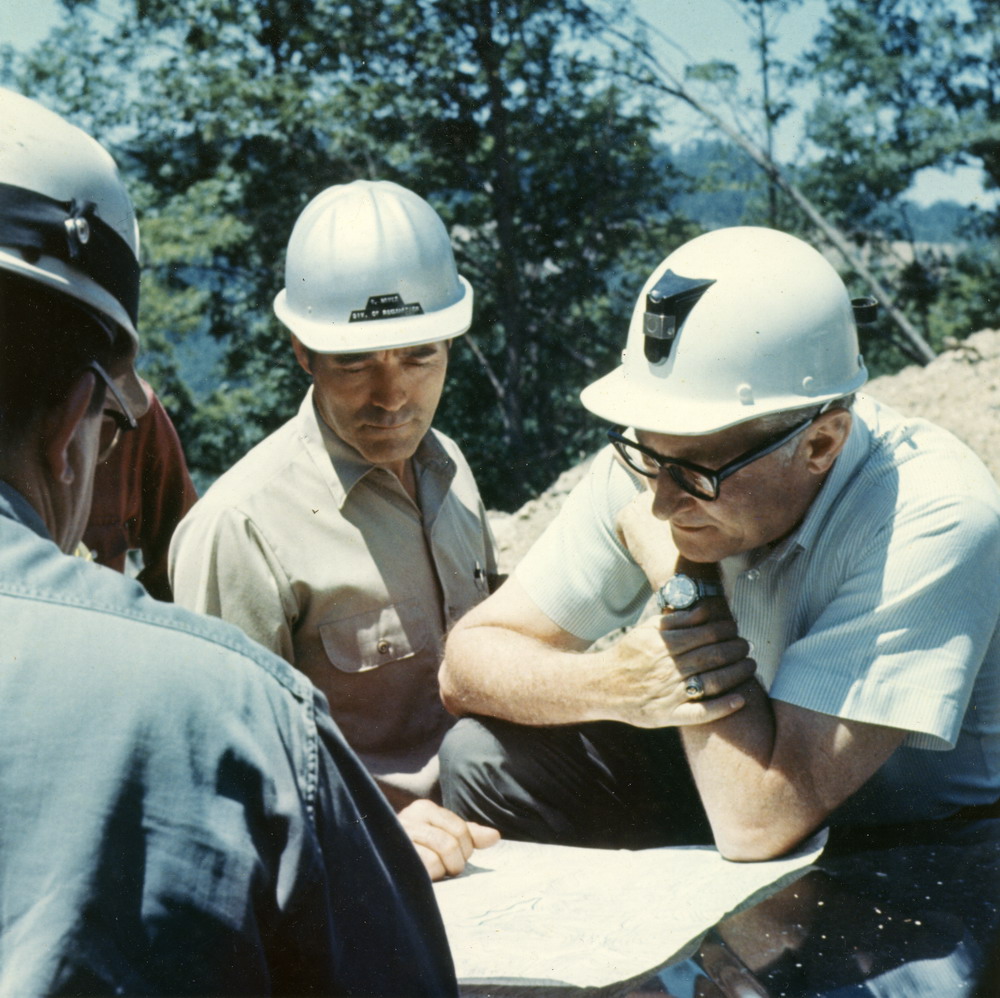

Wendall Ford signing Kentucky’s new reclamation laws into effect. surface mining legislation, 1973. William Hayes, far left, John Roberts, Director of the Kentucky Division of Reclamation is third from left, with other members of the KY Dept. of Natural Resources and Environmental Protection. [hay0206.jpg

William Hayes. [hay0205.jpg]

THE AGGRAVATION LEVEL EXCEEDED

As Wendall Berry said in his introduction to Eric Reece’s book, Lost Mountain: A Year in the Vanishing Wilderness (2006), “A conservationist trying to oppose this enormity [surface mining] must accept heartbreak as a working condition.”

This new job was beyond Bill’s “aggravation” level. Seeing the forests, the streams, and the people swallowed up by the overburden of mountains scrambled and upturned, was a daily heartbreak. Finding a common path somewhere between the needs associated with the employment crises of the region, the national economy, the needs of environmentalists, and the powerful and voracious appetite of industry, pulled from the well of every negotiating experience Bill had known. As the son of a coal miner, Bill understood the lack of a diversified economy and the need for employment. As an environmentalist, he understood the growing degradation of the land. When faced with the stark reality of big money and big industry and big politics, the task would have been daunting to even the most seasoned regulators of environmental law. But, Bill did not see the obstacles. He saw the opportunities and he set about to save as many lives and mountains as possible. But, it was a possibility that could not be ethically maintained or balanced by the regulators. It was an impossible job.

William Hayes with co-workers, KY Dept. of Reclamation, c. late 1970’s. [hay0204.jpg]

The last straw came in 1971 when Governor Wendall Ford met with Kentucky coal operators in Wise, Virginia, where ostensibly he was seeking funds for his gubernatorial campaign. As Stevens tells it, the meeting had one central purpose and that was to convince Ford to fire Bill Hayes. Before Governor Ford could fire him, conscientious friends in the coal operators association leaked word to the press and the firing never happened. Elmore Grim, Director of Reclamation, and Natural Resources Commissioner James Shropshire were prepared to back Bill and to resign if the Governor took any action. Additional ploys were used to try to dislodge Hayes from his position and ease the regulatory oversight in the eastern region, but Bill kept his course and his integrity.

[To view comments of the Congressional Hearing attended by Bill Hayes and Shropshire and others, see: Regulation of Strip Mining: Hearings, Ninety-second Congress, First Session …By United States. Congress. House. Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs. Subcommittee on Mines and Mining, ……

A letter to the Editor of the Louisville Courier-Journal from Don Hastings of Charleston, Indiana, on November 2, 1976, responded to David Ross Stevens article with the following comments

Let’s tip our hats to David Ross Stevens for a job well done in providing us with yet another example of how governmental policies are geared to please big business rather than to satisfy the people’s needs (“Strip-mine regulator charges state laxity.” Oct. 31, 1976

William Hayes’ incorruptible integrity didn’t jibe with the egocentric dishonesty of a few Kentucky politicians — who pressured Hayes out of his job when they sensed future campaign donations from big coal companies were being jeopardized.

The disappointing (although not surprising) matter deserves a thorough investigation to identify and prosecute the administrators and bureaucrats responsible for the indirect dismissal of Hayes as the best strip-mine regulator Kentucky had.

Everyone talks about bringing integrity back into politics, but when are we going to get tough on purging our system of selfish, incompetent, corrupt politicians?

To add injury to insult, Bill also suffered a hospital trip during this time for a laceration inflicted by a coal operator’s punch. The assault charges were never prosecuted but the perpetrator was fined $5,000 for his violation of surface mining infractions. This was only one aggression and intimidation of the many that Bill and his colleagues faced in their enforcement positions. Today there would at least be consideration of hazardous duty pay or policing support, or a more equitable compensation for the rigors of similar enforcement positions, but violence in the coal fields was commonplace in the 1960s and 70s.

Bill said of his experiences and ultimately his decision to step down that, “I have finally come to the conclusion that there is a master plan of confusion by this administration and the plan is working [to the advantage of the coal industry].” Bill had reached his maximum aggravation level in this unsettled career. David Ross Stevens concludes his 1976 article in the Courier-Journal by saying:

… What the coal operators had asked for in 1969, they got in 1976. Bill Hayes is baking whole wheat bread and making wild-grape wine and preparing to visit his oldest son in the Phillippines. Strip mining is far from his mind nowadays.

[The oldest son, Steven Hayes, born at Pine Mountain was a Navy Commander serving at Subic Naval Base in the Philippines.]

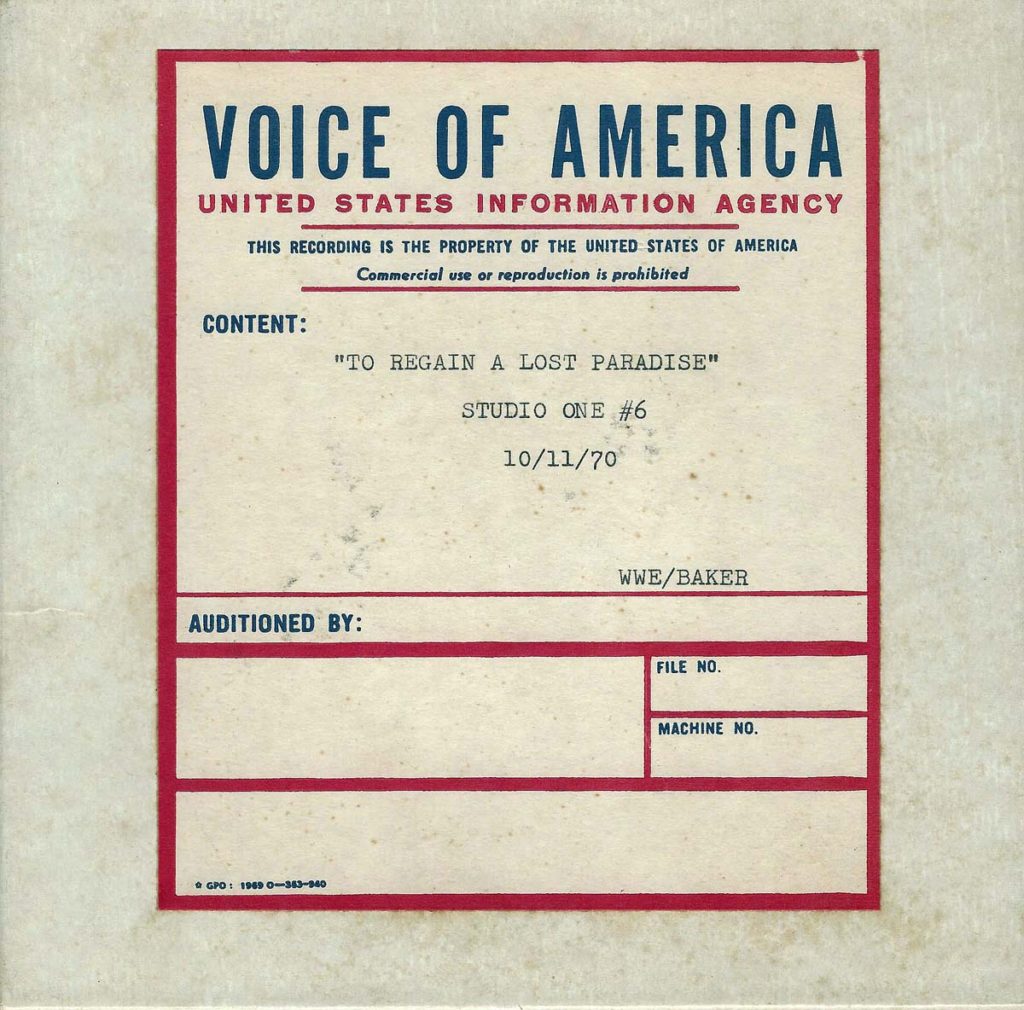

WILLIAM HAYES (Part II): “To Regain a Lost Paradise” – Voice of American Interview

Cover, tape of VOA Interview, “To Regain a Lost Paradise.” October 11, 1970. [Scan0001.jpg]

Kimball Baker first traveled to Whitesburg to talk with Harry Caudill, a Letcher County lawyer whose 1962 book Night Comes to the Cumberlands: A Biography of a Depressed Area, was an early call for intervention in the environmental degradation associated with surface mining and coal mining, generally. Caudill cited the notorious Broad Form Deed as the leading culprit in the growing wasteland — some 40,000 hectares in Eastern Kentucky alone. The growing number of absentee landlords and the pervasive fatalism of many Appalachian families were cited as other causes for the persistence of surface mining by Caudill.

Leaving the law office of Harry Caudill, Kimball walked down the street to also see Caudill’s friend, Tom Gish, another Letcher County advocate for the environment. Gish, the editor of The Mountain Eagle (“It Screams’) the local newspaper, was waging a fierce battle against the growing number of spoil banks in the county and region. His opposition to surface mining had cost him advertisers and for ten years Gish had used his own meager means to continue his fight to save the region’s land and people. When other journalists came to the eastern coalfields to report on the latest excesses of surface mining in the 1970s, Caudill and Gish were often at the top of their interview lists as the integrity of the two men’s perspectives was well known.

Kimball also interviewed families caught in the ugly reality of living with mining on their land and interviews with Dan Gibson and Eva Ritchie were poignant testimonies in the gathering of information on the human impact of surface mining. Landowner Gibson’s work led to the formation of Save the Land and the People and the reporting of Eva Ritchie’s wrenching account of watching her children’s coffins callously bulldozed over the mountain on a strip job only strengthened the images of personal suffering. The media accounts of these personal challenges helped to bring about new surface mining legislation and new laws. Yet, the changes were often not lasting and progress had little legislative and legal tooth. Kimball wrote that the arguments from these early advocates for change were ineffective because they focused on laws and not on what other insiders identified and advocated — “a whole new professional ethic.” Unfortunately, Kimball left the listener wondering how this new professional ethic could be instituted in such a sea of corruption.

Kimball also went to visit coal operator, Bill Sturgill. one of the largest mine operators who according to the Coal Operators Association was “doing a good job” of restoring the land and “looking out for the needs of the people.” As evidence of his contributions to the local economy and the people, Sturgill told Kimball that he had planted fruit trees on his strip jobs to “benefit the land and the fruit industry.” He also cited other efforts to do right by the people whose lives had been disrupted by mining.

It was now time for Kimball to go talk to the State reclamation officer charged with reclamation oversight in the region. He hoped to get the state’s position from Reclamation Supervisor Bill Hayes and other officers. He believed he could then try to weigh his observations against the regulators, the nay-sayers, and the miners. In the interview, Hayes agreed that some of the larger operators were trying to do a good job but most often they also fell short of the ill-defined mark. Commenting on Sturgills’ fruit orchard, Hayes noted that of the nearly 8,700 fruit trees that Sturgill’s company had planted, to date none of the crops had made it to market. If Sturgill intended to benefit from the land and the fruit industry, neither goal had yet been met. Hayes also noted that the grasses and trees introduced on strip mine jobs were only partly effective. He invited Baker to join him on a tour of the region to see for himself. Baker accepted the offer.

On the road to Vicco, a town near Hazard in Perry County, the Baker and Hayes could see in the distant mountains the ravaged land of surface mining and nearby a particularly depressed area of the small mining town of Vicco (Virginia Iron Coal and Coke). Bill remarked to Baker, “Can you imagine what it is like to grow up in this town?” Baker did not respond. The interview faded into Jean Ritchie singing “Blackwater” her famous protest song. Jean, a first cousin of Bill’s wife, Fern Hall Hayes, grew up and had a home in Viper, the same small village where Bill and Fern were building their log home. Bill continued,

“No matter how good it [reclamation] is, it is not enough…. We can only enforce what the people want … What disturbs me most are the thousands of young timber trees that are covered up each week … no plans to take care of them. We can’t continue to cover up the timber …”

What Bill did in that interview was to plant the seeds of ideas that were later to find a home with ARRI (Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative) instituted by Patrick Angel, badge #2 in the new Reclamation Division of the Kentucky Department of Natural Resources.

What Bill did in the VOA interview was to plant the seeds of his ideas but his ideas were not enough in the face of such overwhelming obstacles and fallow ground for compromise. Like natural resources economist Dr. David Brooks, who is also quoted in the interview, Bill advocated for some means to strike a balance between the things we value. Like Brooks, Bill saw the environmental danger looming and tried as a regulator and an environmentalist to encourage the people to take up the issues. It was finally “People Power,” that shifted the balance and Bill was there to help move ideas like those of David Brooks forward. No stripping on slopes of more than 20 degrees; institute a coal tax; and require landowner consent to surface mine, ignoring the age-old broad-form deed. The solutions seemed doable, but this was before money and politics began putting their full weight into the industry.

The interview ended on a refrain that signaled the deep fatalism that continues to run throughout coal country. “The more things change, the more they stay the same.”

WILLIAM HAYES (Part II): Congressional Testimony

In 1976 Bill left his position as the Reclamation Supervisor of the Eastern Coal Fields of Kentucky in the Kentucky Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Protection. He cited as his reason for leaving, “Unable to carry out what I thought were my duties under supervisory personnel.” In the Reclamation Supervisor job, he had been charged to Interpret, implement and arbitrate rules and regulations governing strip mining and reclamation to evaluate the activities of the section chiefs and area supervisors and provide technical assistance and administrative assistance in difficult areas. He had oversight to “inspect and review the work of all subordinates, to conduct scheduled, as well as unscheduled training sessions for field and administrative personnel. He was authorized to review and make on-site investigations of all special activities such as tours, demonstrations, and training schools. Further, he was the front person for all public relations related to surface mining reclamation. It was an impossible job just on the administrative side and he was expected to be in the field. That same year, 1976, Morris K. Udall called for Congressional hearings on H.R., 2, the Surface Mining & Control Act. Udall requested that Bill and others come to Washington to testify before the Congressional Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs as to the need for enactment of H.R 2, the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act (SMCRA). The battle to save the mountains of eastern Kentucky looked like it might have a federal ally.

Following his testimony and the successful passage of the Act, Bill was called back to Washington and this time to be present with other supporters at the Jimmy Carter White House for the signing of SMCRA. This primary federal law that regulates the environmental effects of coal mining in the United States is comprised of two programs: one for regulating active coal mines and a second for reclaiming abandoned mine lands. The second program, that of “orphaned mining” would become the focus of Bill Hayes’ work at the end of his career.

GALLERY II: White House – Signing of the Surface Mining Law 1977

- Jimmy Carter. White House signing of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 [SMCRA].

- Jimmy Carter. White House signing of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 [SMCRA].

- William Hayes. White House signing of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 [SMCRA].

- White House signing of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 [SMCRA].

- Jimmy Carter and gathered guests. White House signing of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 [SMCRA].

- Guests. White House signing of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 [SMCRA].

- Guests. White House signing of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 [SMCRA].

- Guests. White House signing of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 [SMCRA].

- Guests. White House signing of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 [SMCRA].

- Arthur Godfrey. White House signing of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 [SMCRA].

- Guests. White House signing of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 [SMCRA].

- Guests. White House signing of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 [SMCRA].

- Vice President Walter Mondale. White House signing of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 [SMCRA].

- Jimmy Carter (back) and Guest. White House signing of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 [SMCRA].

- President Jimmy Carter and crowd. White House signing of the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 [SMCRA].

WILLIAM HAYES (Part II): Dept of the Interior – Office of Surface Mining 1978

Madisonville, Kentucky. The first training class for the Office of Surface Mining (OSM) Reclamation Officers, 1978. (Bill, second row, fourth from left.) [first_OSM_class_1974.jpg]

It was the morning of May 25, 1978 — 6:00 a.m. Lying in bed, I wondered how much longer it would be before Bill Hayes knocked on the door of my motel room, as he had each morning for the past two weeks. We had been working as a two-man inspection team, crisscrossing the Eastern Kentucky coalfields, trying to be everywhere at once.

Our strategy was to make it appear there were more OSM inspectors than the five we had in the state at the time. We were on a true blitzkrieg. Some operators called us zealots, and a few labeled us storm troopers, but we were mostly known as “the inspectors from hell.”

From the noise outside and the leak in the ceiling of my room, I could tell that it was raining. I just knew that Bill was going to give me his“official wake-up knock” at any moment. Finally, it came.

“Let’s go, Angel! It’s a long way to Harlan!”

Yesterday morning he had said, “It’s a long way to Hazard!” and the

morning before it was, “It’s a long way to Hindman!” I was beginning to

believe that Eastern Kentucky was the size of Texas and Alaska combined.

As a feeble protest, I muttered through the door, “It’s raining, Bill.”

“Yep,” he replied in his eternally optimistic way. “But, you know what

they say — if it starts to rain before 7, it will stop before 11.” Well

then, I thought, invoking half-asleep logic, in that case, it’s okay for

me to get up. After all, this was Bill Hayes.

Bill was our mentor, our guiding light. He was considered “king” of

strip-mine enforcement in Kentucky. Anything he said was correct. If he

said it was going to rain French fries for the rest of the day, then by

golly you’d better bring ketchup.

By 8 a.m. we were well on our way to Harlan County in our leased

metallic-green Blazer, which looked like a big wet June bug. It was

raining so hard the wipers couldn’t keep up. Through the downpour, we

had to find a pay phone so we could make our daily call to the newly

formed Office of Surface Mining headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Each morning, we had to check in with Dick Hall, the number two man

after Walter Heine for inspection and enforcement. Dick called the shots

for most of the field operations. His first decision, after we completed

our training at Madisonville, was to ask that all field people refrain

from issuing cessation orders (COs).

But get this: We were to act in front of the coal operators during our

inspections, as though we could issue a CO.

Shutting down our first operator, regardless of the seriousness of the

problem, had to be delayed because of a legal challenge facing the

agency. Maintaining our delaying tactic was becoming increasingly

difficult as we got deeper and deeper into the coalfields. We knew that

sooner or later one of us would have to do the dirty deed.

On that particular rainy morning, we drove into a service station where

Bill called Dick Hall and was told to investigate a citizen’s complaint

in the Harlan area. “We’re to find a woman by the name of Hazel King,”

Bill said.

Now that was a name I would hear 10,000 times again over the next 24

years. Little did I know at the time that Hazel was embarking on a very

illustrious career as OSM’s most famous and frequent citizen complainant.

As we wove our way deeper into the mountains, I noticed that although

the rain was slacking off some, the clouds hung down below the

mountaintops — a bad sign.

I looked at Bill. “Hey,” I said, “I thought you said it was going to

stop raining.” He grinned and answered, “It’s not 11 yet.” Bill was

never known to be wrong.

Hazel was waiting for us at the opposite end of her swinging bridge

across sediment-filled Clover Fork. She was attired in rain gear. She

was prepared to accompany us, as the new law allowed, on our inspection

of a contour mining operation on an extremely steep slope about five

miles upstream from her lovely mountain home.

The access road to the mine was undoubtedly the worst I had ever seen.

There were no culverts, no drainage controls, and no durable surface. The

road was rutted by heavy coal truck traffic, and water cascaded down the

ruts. The wheels on our “June bug” were spinning like crazy, and it

began to look as if we weren’t going to make it up to the bench.

Bill’s teeth were tightly clenched as he ticked off one violation after

another. “You can tell how good or bad a job is going to be by the way

the access road is maintained,” he said. Bill was never known to be wrong.

When we reached the bench it looked like the aftermath of Hiroshima.

Spoil was piled up helter-skelter. Massive broken highwalls loomed

above. Deep pits of acid water littered the landscape like pockmarks.

And the rain only made it worse. This was truly a “push-and-shove

operation” of the kind seen before the passage of the federal strip mine

control act.

We immediately spotted three active and separate pits of coal where

dozers, trucks and loaders were doing a complicated dance of extraction.

On top of a pyramid-shaped spoil pile, high above this three-ring

circus, stood the operator, choreographing the entire operation.

First, he would point to the left, then to the right. Then he’d wave for

a coal truck to jockey into position. Then he’d signal for the front-end

loader to start loading. Suddenly he stopped, turned and saw “the

inspectors from hell.”

He walked over quickly to find out what we wanted. Bill and I hadn’t

been issued our official OSM credentials yet, so we showed a letter

signed by Walter Heine that said who we were and what our authority was.

Luckily, the operator didn’t challenge us, although he didn’t seem too

happy that Hazel King was with us.

In fact, despite a nervous twitch in one eye, the operator didn’t appear

to be quite the villain I expected. However, I noticed that as Bill

pressed him on a particular problem, the nervous twitch accelerated.

The line of Bill’s questions made it obvious that he was reading the

operator’s eye to locate the serious violations. I believe that’s how

Bill found the landslide so quickly. It was the mother of all slides, at

least 200 feet across and 800 feet down the slope, directly into Clover

Fork. It was one of those slides where you could actually see material

moving down the slope. What really bothered me was the amount of spoil

and rocks still to come. It was an impending disaster — a sedimentary

Sword of Damocles. Bill and I looked at each other. We both knew what

had to be done.

As we walked back to our vehicle, I said, “But Bill, they haven’t turned

us loose yet with cessation orders.” Bill paused for a moment, then

answered quietly, “Angel, we’re going to baptize this agency out there

on that slide whether it’s ready or not, and you’re going to be the

preacher.”

As Bill uttered those words, I looked up at the sky. It had stopped

raining, and by golly, it was 10:50 a.m. Bill Hayes was never known to be

wrong.

With trembling hands, I flipped through all the forms and documents in

my briefcase. Bill kept the operator and Hazel King some distance away

from where I was doing the paperwork. After about 15 minutes I walked up

to the operator and handed him the document titled “Order of Cessation.”

As he stared at it, the operator became motionless (twitch and all), and

his face turned crimson. A few minutes later, all of his heavy

equipment, trucks, dozers and loaders shut down simultaneously, leaving

a deep and foreboding silence. Somewhere off in the distance, a

white-throated sparrow whistled.

OSM had issued its first cessation order, and the coalfields would never

be the same.

The turbulent years of inspection in the coalfields of Kentucky took their toll on both sides of the surface mining debate. While the final years for those inspectors brave enough to place the environment in the foreground were fraught with both emotional and sometimes physical violence, their political support waxed and waned. A letter that William Hayes received from William J. Kovacic, written on August 3, 1995, a full seventeen years later, sheds light on the conflicted work of surface mining inspectors and their struggles in the early years of surface mining oversight.

Mr. William Hayes

Dear Mr. Hayes: Seventeen years ago last May, we met in Madisonville, Kentucky, for the first-ever Office of Surface Mining (OSM) inspector training. Little did we know how difficult it would be to implement the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act of 1977 (SMCRA). As soon as we received our assignments and we spread out over the coal fields of this nation we soon found out though, didn’t we? Life has not bee quite the same ever since.

This letter is an expression of OSM’s deep gratitude and sincere appreciation for your exemplary service during the formative years of the agency. As a leader in the coal fields of Eastern Kentucky during the early years, you provided invaluable guidance and leadership. Our inspection force during that time was, for the most part, “green as a mountain gourd.” You came out of retirement to assist in getting the inspection and enforcement effort of SMCRA off on the right foot. Because of your many years of experience as a State reclamation inspector and supervisor, your seasoned technical skills, and your cool, calm, and collected inspection style, you were the standard bearer for all OSM reclamation specialists. For that, we owe you a big debt of gratitude.

Because of your integrity, I thought of you as the inspector to pay tribute to on the eighteenth anniversary of the Federal Surface Mining law being signed. In paying tribute to you, I pay tribute to the many talented, hard-working State and Federal inspectors for whom we owe so much for our successes to date. The role of the inspector remains as critical today as it was seventeen years ago when we started. Thanks for the high standards you set for us. We struggle each day to reach that standard.

Sincerely,

William J. Kovacic

Field Office Director.

Previous:

WILLIAM HAYES (Part 1)

Next:

WILLIAM HAYES (Part 3)

See Also:

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH V Farm and Dairy II – Morris Years

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH VI Poultry

FERN HALL HAYES Student Staff – Biography

RELIGION Vespers Service William Hayes c. 1942

WILLIAM HAYES Family Photograph Collection

WILLIAM HAYES and KENTUCKY GUILD OF ARTISTS & CRAFTSMEN

WILLIAM HAYES Personal Correspondence

Return To:

BIOGRAPHY – A-Z

GOVERNANCE BOT Chronological Guide

GOVERNANCE BOT Alphabetical Guide to Board Members