Pine Mountain Settlement School

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH

Community – What is Community?

Labeled, “Our Neighbors,” this group photograph taken by a staff worker at Pine Mountain is difficult to read. What was the intent of the photographer, the labeler? What does the image say about “community” when it was taken and what of “community”, today? [Vl_34_1102_mod.jpg]

DANCING IN THE CABBAGE PATCH

COMMUNITY What is Community?

“Community” is generally defined as a social unit of any size that shares common values. Embodied or face-to-face communities are generally described as small and face-to-face interactions, unlike larger or more extended communities such as national communities, international communities, or virtual communities. For example, virtual communities are communities where the members rarely meet in person. Further, “social network” is often used to describe a myriad of virtual communities today. In their most basic sense, all these communities can perhaps be best described as “imaginary communities” as they are often born in the imagination.

Sometimes “community” is used to define a space that falls outside a mutual place of spirit or geography of a place. A community can be a way of defining a value system or a mutual interest of a specific social unit. It can also be used to define and to isolate the “other.” A community is both inclusive and exclusive. A “community” is never neutral, nor even necessarily, stationary.

Pine Mountain Settlement School Workers. Leon Deschamps to far right. Maya Sudo, third from left. [sudo_album_030a_mod.jpg]

In the early years of the School, the community was an idea, not an ideology. It was used broadly and most frequently it was used to define all the social interactions that came together within the unique gathering of people and geography that extended out from — yet, that included the Settlement School and the Settlement satellites of Big Laurel and Line Fork. It was grounded in the idea of Uncle William Creech‘s imaginary community, a community school that he hoped would grow a “bright and intelligent people … ” He knew that such people were found within his identified, face-to-face community but also within an imagined community of influence that resided deep in his mind and many minds of influence. These were the kinds of influence that a school would need to have a chance at changing lives and promising futures.

His community included all those people who could benefit from the lessons a school would and could share both locally and “here and across the ocean …”. For Uncle William, in his active imagination, “community” was written with a large “C”.

THROUGH THE YEARS

“Will you not be, as a child at Pine Mountain recently described [by] Martin Luther, ‘A far-minded, clear-seeing citizen of the day,’ and help us again?”, wrote Ethel de Long in a 1931 appeal letter. Though she invoked the name of Martin Luther, there was no sectarian intent. What she sought was beyond the sectarian borders of religion. What she wanted was a community comprised of “Far-minded, clear-seeing citizens …”

During the early years of the School “Community” was a much-used word and an allusion drawn by staff at the School. Further, it was and is an idea central to most discussions of settlement work and education, whether rural or urban. It is frequently referred to in histories of the Settlement Movement and Settlement School discussions. A community is what most members of a collective unit can intuit but which often evades a succinct definition. It can be the memory, loyalty, the shared practice of everyday life, an abiding hope, the Eternal….but it is not any one of those singular things. I\At Pine Mountain Settlement it is none of those things alone.

On May 20, 1942, the boarding students in the Co-op class at the School wrote a narrative to accompany a film made by Virginia and Ray Garner who came to Pine Mountain under a grant from the Harmon Foundation. The film was charged to depict the work of the student cooperative program and particularly the students at work in the cooperative. or “Co-op” class I sought to bring images forward about the management and activities of the curriculum that was determined to place an emphasis on a “sense of community” by engaging students in various community jobs as part of their curriculum. The following is a short narrative excerpt from a skit that sought to demonstrate the idea of a Community Group Co-operative enterprise:

Master of ceremonies (Hattie Sturgill, seated in center) speaks:

Generally speaking, our Community Group is concerned with anything but dry figures and facts. However, we have compiled a few and we want you to know that:

Home visitors [students] visit approximately 100 families weekly.

One girl averages 15 visits on each field day or about 600 visits during one year.

Six home visitors make about 3600 home visits per year.

Each girl averages walking 12 miles on her field day, 72 miles per week for six girls, or about 3000 miles per year for the group.

Each girl puts in about a nine-hour day, which amounts by the end of the year to about 2000 hours for the group.

Each girl puts in about a nine-hour day, which amounts by the end of the year to about 2000 hours for the group.

“School visitors (3 persons to a squad) visit five schools weekly, covering about 25 miles weekly, or about 1000 miles per school year (these are pre-rubber rationing figures, you know when we could still use the bus). Each person puts in about 100 hours per year at the work, or 1400 hours aggregate for the group.

Lela Christian, Nan Milan, Stella Taylor, Nancy Jude. Community Service Workers, c. late 1930s. [duplicates_069.jpg]

“Early in the year five girls traveled weekly to 4 clinics, each traveling an average 12 miles per trip, 1200 miles for the year, each putting in eight hours per trip, 40 hours per week for the group, 1200 hours for the year.

Our packhorse librarian has been able to function only intermittently (due to Sunny Jim’s [the horse] infirmities) but we figure that he has traveled about 15 miles per week for about 26 weeks, or 625 miles, distributing about 40 books and periodicals, or 1000 for the year, putting in about 200 hours.

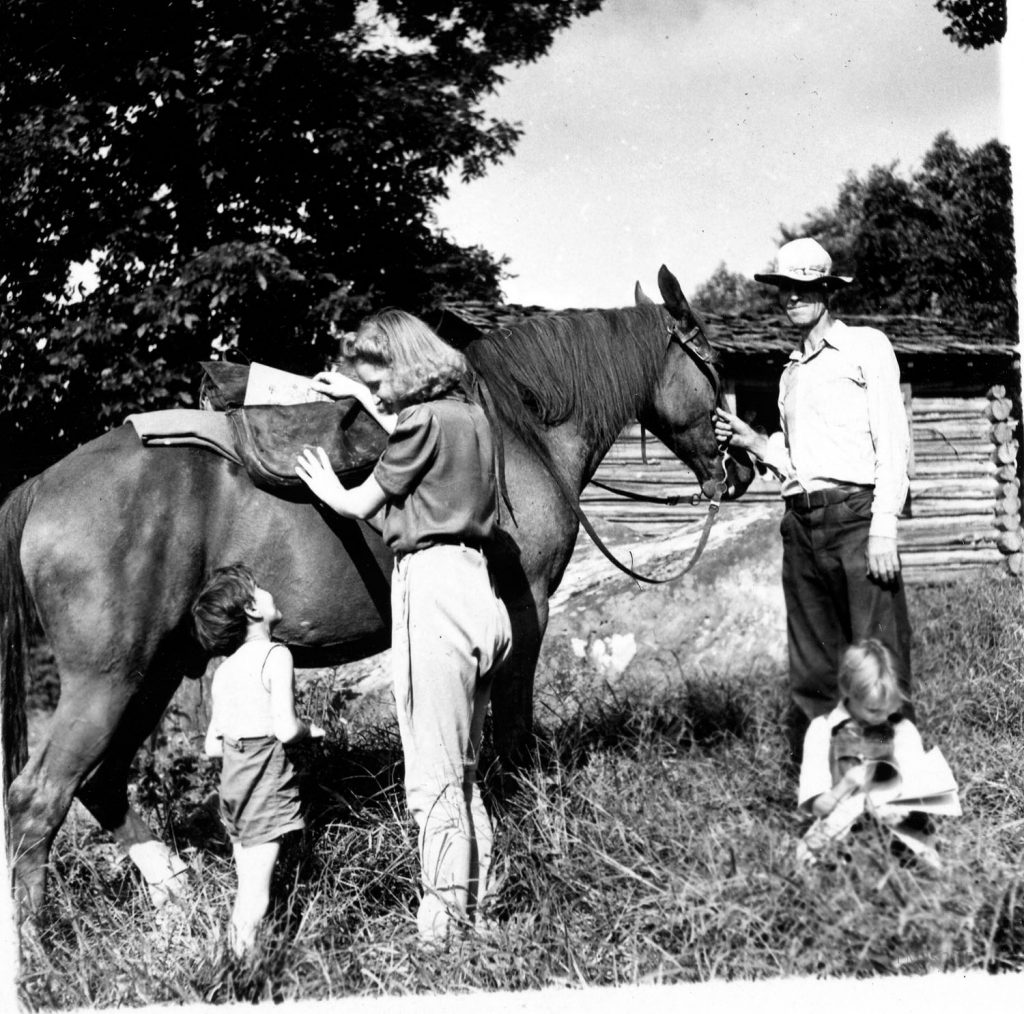

Ruth Shuler [Dieter] a librarian on horseback, delivering books as part of the cooperative program. c. late 1930s. garner_006 (122)

One girl and sometimes two per week spend a day at the Infirmary, 6 hours each, about 360 hours per year serving about 5 people during the day.

So we estimate a total of over 5000 hours work, some 6000 miles covered.

About 1,800 contacts made annually at clinics.

About 18,000 contacts made annually at schools.

About 20,000 contacts made annually at homes.

About 3,000 contacts made annually by packhorse librarian and infirmary girls.

A grand total of 42,800 contacts. [annually]

We learn In sociology that every contact with another person has something to do with making us what we are, so surely those 42,800 contacts have done more to us and to those we have met and known than we can begin to realize right now.

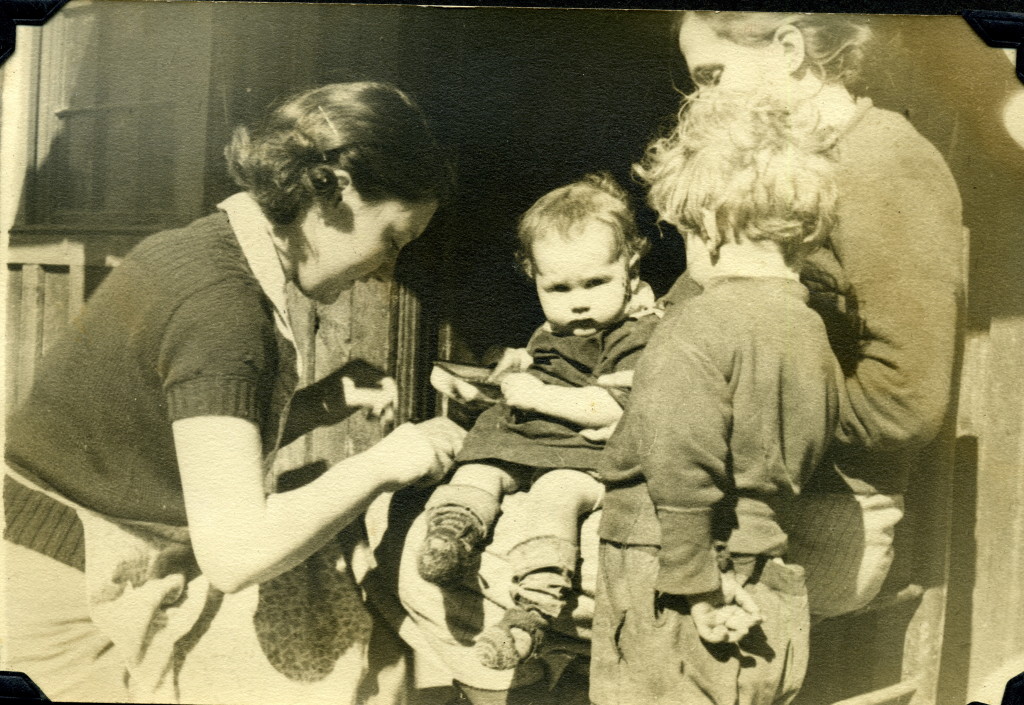

A Nurse tends to children. Early 1940s ? [rood_012.jpg]

In the June 1975 Notes Alvin Boggs, in the same spirit of community appealed to the community to assist Pine Mountain in the development of a kindergarten program:

We are particularly proud of community initiative and responsibility in projects of long-time concern to us. Some of our neighbors have asked for help in continuing kindergarten service for their youngsters, as a reduction in federal funds threatens to restrict the public school kindergarten program. We must again be alert to community needs as we explore every possible way to help our youngsters.

The idea of community has a peculiar relationship to time. It is both timeless and personal. It can stand in relation to the nature of the time process but, generally, it is outside that time process — that numbers process. It is timeless. But, it is also political, religious, and social, and it is often strongly governed or directed inside a personal time sense and often an ideological mindset that has its source in social media or familiar community tethers.

Even narrower is the individual response and sense of community as it relates to place, family history, tribal loyalty, sexual orientation, church affiliation, political party, etc. Califates are communities, as are political parties — Democratic, Republican, Libertarian, Green, etc.. Time, or, in another sense, this non-time dimension, can change the membership of specific organizations and dictate the organization of that membership — that community of a specific time. Yet, being a timeless community can reveal the spirit of place within a group and lead to a discussion of the “old times” a place outside of current community and time..

This timeless idea of the “old-times” can immediately evoke nostalgia for certain values held by a community. This tangled time in communities allows the folding back of values and views. In the course of one lifetime it would be very rare to find individuals who only participated in one community. It is just as unlikely the community stayed the same through measured time.

![Line Fork community, dancing during the Baker years, early 1940's. [line_fork_005c]](https://pinemountainsettlement.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/line_fork_005c-1-1024x612.jpg)

Line Fork community, dancing during the Baker years at the settlement extension -early 1940’s. [line_fork_005c]

How did Pine Mountain come to its view, or views of “community?” How did it define its community? What were the sources of influence on those ideas? How has the sense of community at Pine Mountain changed through the years? These were and are questions important to the School’s sense of mission, to its sense of place, and to its future survival. Pine Mountain Settlement School, as an educational facility, has been remarkably consistent in its sense of mission and its sense of place, and in its conception and identity with the idea of “community.”

This consistency can be seen in where the School looked to draw its information and inspiration; its sources of influence. It can especially be seen in the photographs taken through the years that visually document the idea of community. Photographs can provide a graphic record of change in communities that the written record may fail to record. The personal ideologies of administrators, the literature read by the staff, and the vision of the administration of the School. All may reveal other consistencies, other avenues of exploration but most often these influences hold transient measures. What the community wrote and read at Pine Mountain in its early Boarding School years, is rich with consistencies. Yet, on closer view those consistencies are enigmatic. Photographs, while harder to read than documents, when they are aggregated and studied closely, they often are more consistent and revealing in their messaging. .

FAMILIES AND ‘PLACE’

Photographic sources strong contribute to an understanding of community in the Pine Mountain Valley. They also draw vivid images of the practical and historical roots of the many families who settled and evolved within the mountains and valleys of Eastern Kentucky. The populations were served by varying school models and by the older cultural artifacts they continued to carry forward from Europe or have treasured through time. Community is a process that always looks forward and looks backward.

More recently, the Pine Mountain School declares that it seeks to reach far beyond the roots and the geography of the early Valley community members. This broad vision now seeks to support and build a larger self-aware community of environmentalists, civic-minded citizens of the world, and caring neighbors. But, has it been successful? America is slowly joining a growing worldwide community that is self -aware. Many corners of the world now advocate for the value of ecology over that of economics. All too soon, however, economics took over in the driver’s seat. In many ways, the economics of place have not opened the valley to the world but has again helped it circle the wagons — have enclosed Uncle William’s vision. That vision of a school that seeks some purpose or value to the larger world became mired in an economic world that was driven by money — timber, then coal. Yet, as the School spiraled forward, like Spangler’s world, it also continued to circle back to the familiar and basic comfort zones of the local. The history of community at the institutional level? It seems remarkably consistent in its deepest values — that of staying connected with the “local”level, what is commonly called “place.”

While much of what we call “place” and “community” moves forward with its familiar artifacts, institutions such as that of Pine Mountain, often moved and are moving along with a remarkably consistent body of ideas about “place”. In the case of Pine Mountain School, the record is an expansive landscape of literature, architecture, music, dance, education, environmentalism, and a deep faith in humanity. Its history is a remarkable record — one very engaged institution; one deeply concerned with the many levels of a community “place”.

RELIGIOUS AND PHILOSOPHICAL “PLACE”

Josiah Royce (1855-1916), philosopher and ideologue, shows up frequently in letters and quotes of staff. Royce struggled with the idea of community in his lectures. One lecture, “The Community and the Time-Process,” from The Hope of the Great Community, was Royce’s last work, published in 1916. This was just three years after the founding of Pine Mountain Settlement School. It captures the sentiments of the earlier time. For Royce, a deeply religious man, his “community” … “…is that thing which allows us to study the world of the spirit” [Roth, John K. The Philosophy of Josiah Royce, p.368].

Royce explains:

The psychological unity of many selves in one community is, bound up, then, with the consciousness of some lengthy social process which has occurred, or is at least supposed to have occurred. And the wealthier the memory of a community is, and the vaster the historical processes which it regards as belonging to its life, the richer — other things being equal — is its consciousness that it is a community, that its members are somehow made one in and through and with its own life. [Roth, 361-2]

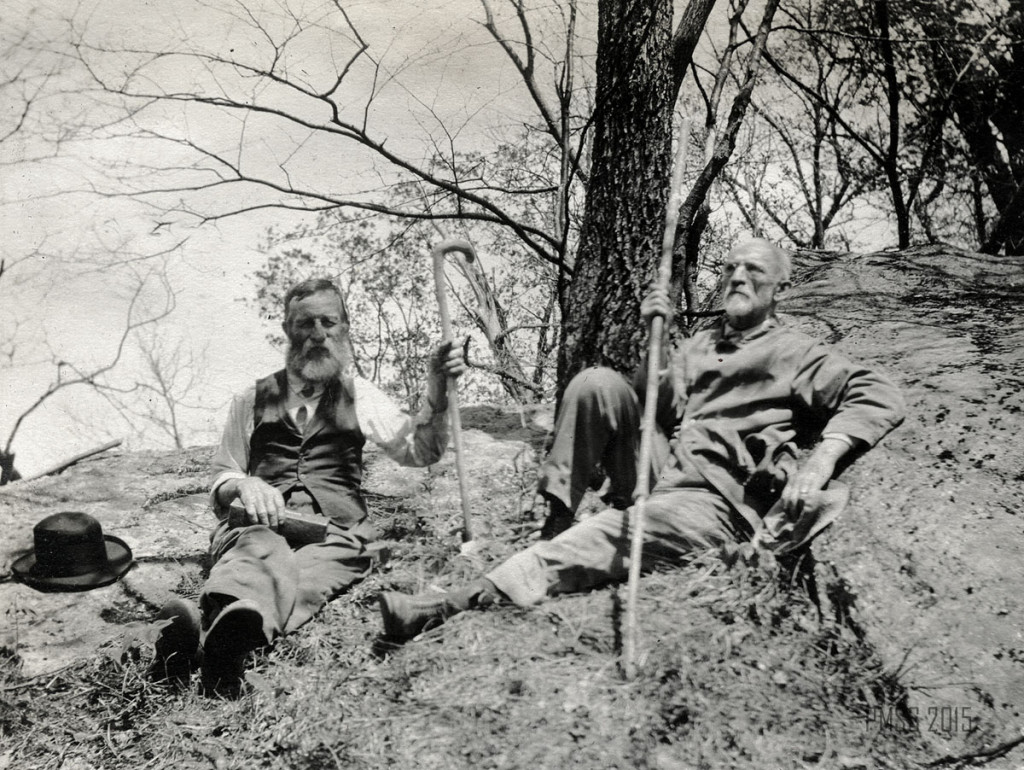

0056a P. Roettinger Album.”On the mountain top. Uncle Wm. Creech and “Old Mr. Man [Philip Roettinger]” [Two older men: William Creech and Philip Roettinger sitting, Creech on left holding a cane, hat on the rock at left, Roettinger at right holding a walking stick.]

As the School moved into the later years of other administrations, the imagined community shifted in small steps. There was also a gender shift in administration. The most dramatic shift came during the years leading up to World II (1931 – 1941), when Kentucky supplied one of the largest numbers in the country of volunteer soldiers. Under the long administration of Glyn Morris, these years are often referred to as the “Boarding School Years.” During this time there were common threads of sentiment for living the imagined community, but there was a stronger shift toward the reality of living within a larger world. This expanded view can be found in the School literature and in the books read and recommended by staff and administration — and in the letters and writing of students, where there is a grasp of the world community that astounds. Yet, even in that expanded horizon, the sense of a “common community” ties the remote school to the world view with a common thread of empathy.

In the donated library of books belonging to Helen Bray de Long, sister of Ethel de Long Zande, Director, one author that stands out is that of Hugh Black, (March 26, 1868 – April 6, 1953), a Scottish-American theologian and writer. Black, emigrated to the United States in 1906 where he had accepted a position on the faculty of Union Theological Seminary in New York, as Chair of “Practical Theology.” He maintained this position until 1938 when he retired. Including his work at Union Theological Seminary, he accepted a position in 1908 as the pastor of the First Congregationalist Church in Montclair, New Jersey, the hometown of the de Long family. While at Union Theological Seminary in New York, Black worked alongside such luminaries as Reinhold Niehbuhr and with students, including Glyn Morris, who, at the age of 23, came as the new Director of Pine Mountain Settlement School in 1931, directly out of Union Theological School.

The influence of Union Theological school was about to exert an important influence on Pine MOuntain Schools communities. In addition to his accomplishments at Union Theological, Black had received an honorary degree from Yale in 1908 and from Princeton University, and also, across -the-sea from Glasglow University in 1911. As the pastor of the Congregational Church in Montclair, N.J., where Helen Bray de Long and her family lived and attended the church, the paths of de Long, Morris, and a deeply held religious and educational paths were joined.

The titles of Black’s many books speak to his philosophical and religious focus: Friendship (1898); Culture and Restraint (1900); Christ’s Service of Love (1907); The New World (1915); The Adventure of Being Man (1929); and Christ or Caesar (1938). This last book brings his discussion back to the conflict of ecology and economics which continues to occupy both religious and philosophical debate today and marks the pre-war period of disillusion leading into Worrld War II.

There are numerous reflections of Black, Niehbur, and other Union theological luminaries sprinkled throughout the writings of the founders of Pine Mountain, Katherine Pettit, and Ethel de Long Zande, and in the writing and thought of Glyn Morris during his ten-year direction of the School at Pine Mountain. There are passages in the writing of de Long and Morris that ring as familiar as the themes in the philosophy of Royce, of Black and other “communitarians.”

The idea of community was, for many of the turn-of-the-century authors, a quasi-utopian dream and the ideological theme of community runs throughout many of the works of many authors of the time and is not just unique to Pine Mountain. However, at Pine Mountain, the idea of community is like a weft that weaves its way throughout the one-hundred-year history of the School. The heady theological idea of community at Pine Mountain Settlement always seems to maintain a remarkable balance with it’s agrarian and pragmatic warp, introduced by Katherine Pettit but tempered by Ethel de Long’s and Glyn Morris’ urge to celebrate the philosophical and theological.

The idea of community may be held together by the warp of “place”, but it is warp and weft that builds and binds the whole cloth of the physical Community with a large “C”. It is a weaving colored by the black of coal, the sap-green of the summer forest, the red of weathered barns and morning fog, and the brilliant orange of October maples. Pine Mountain is a community that hears the whippoorwill and weeps, yet, clatters its pots to send the crows and foxes from the garden. It calls forth the Great Horned and the Barred Owl with digital sounds on night-time environmental walks and imitates the warbler hidden in the paw-paw tree. The quiet forest walks with native birds is easily tricked by the mockingbird and a migrating stray. It is a community of Eden and of corn-pone and colloquialisms. It is a community.

EDEN, CORN-PONE AND COLLOQUIALISMS

The Pine Mountain community is not, as some want to foreground, just a people of corn-pone, shucky-beans and fat-back. It is also a community with a busy Wal-Mart and Food City or Dollar Store where on Saturday morning families cross the Pine Mountain to the town of Harlan to cart home fast food and beer. At the School where Pine Mountain’s coarse entire wheat bread is still baked, it also competes with Col Sander’s fried chicken. The fat fried chicken on Sunday still can mix with last night’s leftover squirrel and gravy in a neighbor’s home. It is the Butterball turkey and marshmallow sweet potatoes on Thanksgiving and the sweet potatoes mashed with rich butter and enlivened by conversations around the rattlesnake in the garden or the sharp memory about the latest relative dead from black-lung, cancer, or oxycontin and now — COVID.

The community history is still remembered in the tales of the secret still on the hill, the gun that killed the revenuer, or the neighbor, and also the ABC (Alcohol and Beverage Control) store and the drug deal on the lonely road to addiction or incarceration. It is family lies and secrets, loves and deceits. It is J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy (2016) and Maimon’s The Twilight of Hazard (2021). It is Horace Kephart’s Our Southern Highlanders ( 1913) and Emma Belle Miles’ The Spirit of the Mountains, and James Still’s River of Earth. It is the newborn and the “Funeralizing” that gathers the dead to remember. It is the set and turn-single, the musician and the song, and the American Idol newly crowned. It is the gentleman come a-courtin’ and the “hook-up” online. It’s the ancestor who was a mail-order bride and it is Match.com. It is the tale of the child named “Alfreda” — named for Dr. Alfreda Withington, the Big Laurel Medical Settlement doctor that delivered her. It is also “Brittney” — as in Spears and the now-common “Justin” — as in Beaver.

Community is also vegetables and flowers from shared seeds and the new canning techniques learned from extension workers and from Grow Appalachia, the Appalachian Sustainable Agriculture project, and the new-old “farm to table” ethos. It is the wedding in the Chapel and the divorce in the County Court House. It is the success of the grandchild that graduated from Eastern Kentycky University or UK. It is a community we recognize throughout our country and yet, so many find it unique. What makes a “community” unique? Is it a kind of celebration? Is it physical or all in our heads? Is it always time folding back on itself and captured in the lens of the day, the net of our memories.

A newly married couple in the Pine Mountain community, standing next to a well. [Vl_34_1111_mod.jpg]

Community is the marriage that brings people together in celebration of their common memories. Celebrations often can mark the seasons. In the history of Pine Mountain, there are many celebrations: Fair Day that shows off the Fall harvest; May Day that remembers the European origins of many who trace their family to England, Scotland, Wales, Germany, and other countries “over there.” Community is also communion with others of like faith. It is the baptizing in the creek and the loud “Amen” in the church service. It is speaking in tongues and celebrating High Mass. It is the sweetness of boiled-down sorghum and the “black-strap” in the bottom of the pan.

While Community is sometimes sweet like the boiling down of sorghum molasses in a community ‘stir-off’, it can sometimes run sour. Yet whiskey is made from sour mash and distilled in a mountain moonshine still it could turn a Saturday night into a raucous party or a deadly fight. With a quart jar full of forgetting, even “Community ” can be obliterated. In fall, it is the gathering of walnuts and hickory nuts and in early spring and late winter, the gathering of the slow drip of maple sap for syrup. Sweet and sour, bitter and bland, sharp and mellow, community also has variants and limits.

Community and celebration have a close association with the idea of “gathering.” It many ways it is like the unique “Funeralizing” at the end of life…. a gathering of memories and a summing up of friends and family long dead. The gathered pass slowly by the coffin of those who so recently were part of their community and they and they reflect. “Too early” they say. “Too young”, and some pay respect with, “He was an ornery old cuss, but I shore liked him,” as they join their community to pay respect. Those who went before were part of their “community.”.

COMMUNITY AND IDEAS

Always the ‘pragmatist,’ Josiah Royce, again reminds us of our community. A friend of John Dewey, of William James and Charles Sanders Pierce, Josiah Rotce challenged his contemporaries to find the answers to some very tough questions that often run through communities. The most challenging of these questions are those entangled with the idea of what constitutes a “community.” Royce lived and wrote during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century — the years between the wars when communities were undergoing rapid changes due to industrialization. There is no evidence that Katherine Pettit, ever read Royce, but she was ever the pragmatist, as he was. As founder and director of Pine Mountain Settlement School, Pettit was keenly aware of the shifting social, economic, and political climate of her time and frequently she called into question what it meant to be a “community” as she stood on the edges of all things social. Unlike her partner Co-Director Ethel de Long she did not crave companionship but seemed to draw her energy from the whole of bringing ideas together and into the light.

There is evidence that Pettit, and those she worked with on a daily basis, frequently challenged new ideas and positioned their own perceptions against those of the surrounding community they served. What is meant then to be part of the Pine Mountain community? As strong as Pettit’s ideas and personality were reported to be, there is evidence that she and other workers were not social dictators when defining how the local must be managed. Pettit and other directors clearly sought to bring their views and their visions in line with those of the settlement’s service area —its community — its people. Together both saw the Settlement School and its surrounding area as a fluid environment of ideas that drew its strength from the varieties of the ideas. While Pettit, the founder of the School, may have been the least communitarian in practice, she was the cement of ideas.

Many Directors and Workers have passed along a rich record of their celebrations and their efforts to “figure it out,”– this elusive “community” question. Their intense questioning is evident throughout the archival record of the School. The record, more questioning, than dictating, is a testimony to the strength of ideas found within the one-hundred-year archival history of the Pine Mountain Settlement School institution. Appalachia and its people are not entirely unique nor is their life and livelihood an enigma, if placed alongside communities in this rich and diverse land of the United States. In its entirety the people, the place, the ideas are all a famiiar enigmatic landscape. Numerous authors have given their voice to our collective history — to our sense of “Community.”

It is no accident that the phrase, “In the Spirit of Pine Mountain,” has become such a favorite phrase in the literature of the last fifty years. The “Spirit of Pine Mountain” is pervasive and central to our collective sense of COMMUNITY.,

Through Royce and others the questions around “community” have been given complex theories and elaborate arguments. Through authors such as Uncle William, Ethel de Long Zande, J.D. Vance, James Still, Allen Maimon, and Emma Belle Miles, and a myriad others, the idea of community has been explored. Speculations have been made. Community has been found and sometimes lost to vanity, and isolation. Yet philosophers and writers such as Josiah Royce, Allen Maimon, Rhinehold Niebuhr, and even J.D. Vance — so many others whose philosophies shaped ideas in the minds of Pine Mountain’s leaders in the formative era of the School and continue shaping new ideas. The founders of Pine Mountain and the founders of the country tackled hard questions of moral values, religious ideas, political choices, and imagined the world they wanted to live in.on a national level early on. It stuck. Yet, at their most essential, the views of deep thinkers, and those who shared this intellectual and philosophical, and theological journey to find “community”, did not arrive at the same destination. “Community” and “community” remain elusive. Perhaps it is because we rely on the questions asked of each individual as they are confronted with the nature of their singular existence and the meaning of their singular lives. Royce and Uncle Wiliam Creech had this self-inquiry in common. So did so many individuals who passed through Pine Mountain and came face-to-face with the “community” and their “community.”In all its permutations, community, both within and without the School, have begged the question, “What is Community?” The struggle with what it means to belong to and what it means to be a part of a community is a life struggle. We are all changed by our experiences in communities of our choosing and our challenge to know the community can often be measured by our comfort. Many of these comfort zones are similar no matter the geography. The evolutions of comfort are often measured by our flexibility, and are here captured in the writing of the workers at this Pine Mountain Settlement School and those who live or came from the surrounding geography. But, importantly, it is often the photographs and the visual images in our heads that build “community.”

In the photographs taken at Pine Mountain Settlement, in the stories told and re-told and in the celebrations retained and abandoned one can get a sense of place and a sense of community. Events that speak to “Community” within the Pine Mountain region are recorded by the many individuals who spent time at the School and also by their neighbors who lived nearby in the joined Community.

Staff workers at Pine Mountain, c. 1918. [sixteen_staff_mod1.jpg] Luigi Zande, ?,?,?,?,?,Evelyn K. Wells, ?

THE COLLECTIONS

The following materials gathered under COMMUNITY CELEBRATIONS and GUIDE TO FAMILIIES IN THE PINE MOUNTAIN VALLEY COMMUNITY, capture moments in the lives of hundreds of individuals who shared this special place, the Pine Mountain Settlement School and the Pine Mountain valley and surrounding hollows. The materials and illustrations pulled from the PINE MOUNTAIN COLLECTIONS reflect the response of an isolated region coming to terms with industrialization and later with technology. The visual images often hint at the shifts that industrialization brought to the people’s understanding of community but there are deeper shifts also at work in the later photographs.

More recently the changes in the community of the Pine Mountain valley are marked by the tensions of technology: the digital divide; the distraction of television and games and other media formats; robots and the loss of jobs; immigration; the collapse of coal in an undiversified economy; opioid addiction and other complex contemporary shifts.

Stream Ecology class. Environmental education class – St. Francis School, 2011 (?) [st-francis-019]

In 2013 the Pine Mountain Settlement School community paused briefly to remember the course of its 100 years and then moved on. It is wished that the reader will grasp through the illustrations found in COMMUNITY – CELEBRATIONS and throughout the web site what it means to both build community and to live within it. Every day is a celebration of life as we move on through our unique life. This world is our broadest Community and we share the responsibility of sustaining it and cherishing it.

Helen Wykle

**********

Maimon, Alan. Twilight in Hazard: An Appalachian Reckoning. 2021.

Miles, Emma Belle. The Spirit of the Mountains. 2016.

Miles, Emma Bell, Steven Cox (ed). Once I Too Had Wings: The Journals of Emma Bell Miles. Ohio University Press, 2014.

Roth, John K.. The Philosophy of Josiah Royce. 1972.

Royce, Josiah. The Philosophy of Loyalty, New York: McMillan and Co. 1908.

Still, James. River of Earth. 1940.

Vance, J.D. Hillbilly Elegy. 2018.

See Also:

ALICE COBB GUIDE TO STORIES, WRITING AND LETTER COPIES

COMMUNITY GROUP ASSEMBLY May 20, 1942

ETHEL DE LONG TALK – “SCHOOL AS COMMUNITY CENTER” 1915

MARGARET MOTTER WRITING: “TIME MARCHES ON IN THE HINTERLANDS”

“NEVERSTILL“ Poem

SURVEY OF COMMUNITIES SURROUNDING PMSS 1934-1942