Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 09: BIOGRAPHY – Staff

Series 18: PUBLICATIONS RELATED

“In the Line Fork Country” 1924

by Anne Ruth Medcalf

Nurse, Line Fork Settlement, 1921-1924

“A MOUNTAIN MADONNA” – “American Child Health Magazine,” Dec 1924, p. 506. [lin_frk_1924_001_madonna.jpg]

TAGS: Anne Ruth Medcalf, In the Line Fork Country, 1924, Southern Highlands, self-sufficiency, isolation, Line Fork Settlement, Pine Mountain Settlement School, game-following, immigrants, county schools, teachers, public health nurses, Sunday School, industrial workers, community, nursing visits, child welfare, health education, Mosaic health laws of the Old Testament, Child Health Organization, trachoma, health clinics, Health House, hot school lunches

ANNE RUTH MEDCALF 1924 In the Line Fork Country

TRANSCRIPTION

[lin_frk_1924_001.jpg] – Cover, page 1.

[Handwritten notation at top of page: “American Child Health Magazine – December 1924” and at bottom of page: “Mrs. Floyd Cornett – Coil [Coyle] Branch -”]

This Kentucky mountain mother, descended from generations of Americans,

is of the Line Fork People, whose story follows.

[lin_frk_1924_002.jpg] – Page 2.

In the Line Fork Country

ANNE RUTH MEDCALF

Public Health Nurse: Head Worker, Line Fork Settlement

“THE CABIN BUILT FOR THE ‘FOTCHED ON’ TEACHER AND NURSE” – “Child Health Magazine,” Dec 1924, p. 507. [lin_frk_1924_002_cabin.jpg]

The Southern Highland area includes the four western counties of Maryland, the Blue Ridge valley and Allegheny Ridge counties of Virginia, all of West Virginia, the eastern third of Kentucky and Tennessee, western North Carolina, the four northwestern counties of South Carolina, northern Georgia and northeastern Alabama. This region, although not frequently considered as a contiguous tract, is really one geographical unit, lying within nine states and covering approximately 112,000 square miles—an area nearly as large as that of New York state and the whole of New England. Within its boundaries is a land of mountain ridges, plateaus, valleys, coves and creeks.

Conditions in the highland area vary greatly according to the accessibility or inaccessibility of the place in point. On the railroads and in places where travel is easy there are large towns which are much the same as towns of like size in other parts of the United States; in the more readily approachable and fertile valleys there are smaller towns and communities and these, as well as the mining villages in this region, have problems similar to communities of their respective classes in other sections of the country. It is the rural and super-rural sections the inaccessible areas—which have their peculiar problems and which command particular attention.

In these super-rural sections the wide valleys become narrower, the hills close in, the “bottomlands” are more scarce, until finally one is shut in by walls hundreds of feet in height. Around the mouths of creeks the people are more or less prosperous. They own the rich “bottomlands,” raise good crops fairly easily, and live comfortably, though simply. Farther “up the creeks” and in the coves hillside land is used for the crop of corn and beans and the garden plot. Clearings in the timber on the hillsides are used for several years until the good surface soil is washed away when other clearings are made farther up the mountain side. Frequently one sees a whole hillside that has once been cleared, the lower part now grown up in stubby trees and bushes, while near the summit in a seemingly inapproachable place is the usual almost perpendicular field of corn. The inaccessibility of these “heads of creeks” and coves can be but vaguely described by saying that the creek beds often serve as the road beds and that trails over the ridges are but narrow paths through brush and undergrowth.

In the earlier days of these settlements there were no roads or mails. The inhabitants had to go from 50 to 100 miles to obtain necessities…

[lin_frk_1924_003.jpg] – Page 3.

…such as salt, and so forth, carrying enough back on their pack horses to last several months.

Neighbors were far apart and each head of a family, besides being a farmer and raising his own food, cotton and wool, was also his own carpenter, cobbler, miller, barber, veterinarian and blacksmith, while his wife carded, spun and wove all the cloth that was needed by the family. An especially gifted neighbor frequently served as mid-wife, as dentist if able to use the “toothpullers” skilfully, or possibly as gun-maker.

Jacks of All Trades

This total dependence upon themselves for generations has made of the people in these regions an intensely individualized and independent group. And today, with considerably changed conditions, they still remain much the same in character. Now there are some roads and the mail is carried on horseback from the nearest railroad point each day, and such supplies as salt, sugar, coffee, a few canned goods, shoes, cheap cloth, and so forth, may be bought in the little country store at the fork of the creek which serves not only as general commodity store and post office but also as the common meeting place for the vicinity. The head of the mountain family continues to be his own house builder and blacksmith, and is still dependent upon some neighbor for the grinding of his corn into meal, the making of his splint-bottomed chairs, and such medical services as his wife and family might need in childbirth or in sickness. At these times the “grannies” are still called upon to officiate or to administer the traditional remedies of roots, herbs and barks. It is needless to say that while many of their curative measures have been tried and proven, many of them are based solely upon superstition and ignorance.

The Line Fork Country

On the steep north slope of the Pine Mountain in Kentucky, which is the head-water country of the Kentucky River, is situated the Line Fork Settlement, an extension development of the Pine Mountain Settlement School. Here the Pine Mountain is a natural but formidable barrier. The valleys are deep and narrow. There is little bottom land. Local tradition says that the people who settled near and at the head of Line Fork were for the most part the “game followin’ sort.” At first they merely came on extended hunting expeditions because bear and deer were plentiful, but as the broader and fertile valleys where they lived became more thickly settled it was necessary for some to push on, and naturally attracted to the new land by the abundance of game, these hunters gradually brought their families to settle. Large tracts of land were available but small clearings of virgin soil yielded them sufficient grain for their simple needs and with game plentiful they were able to live comfortably according to pioneer standards. It is said that most of these first settlers were of Scotch-Irish, German and English descent and came directly from North Carolina, their fathers probably having migrated from the frontier sections of Pennsylvania during the great movement southwestward following the Revolutionary War and just previous to the year of 1800. Some few were English immigrants who pressed on to the mountains from the southern ports of Wilmington and Charleston.

The Crops Are Corn and Beans

At the present time neighbors are closer on Line Fork and its branches than they used to be. Large tracts of land are no longer the rule, much of the surplus land having been sold off to outside coal and timber companies some twenty or thirty years ago. A high percentage of the inhabitants still own land, varying in amount from two to two hundred and fifty acres. The remaining number rent either from local land owners or from the coal and timber companies. This land, however, has been more or less impoverished by the continual growing of corn and beans on it, making the production of adequate crops more and more difficult as the population has increased.

Four years ago the people at the head of Line Fork, having observed the work of the Pine Mountain Settlement School, seven miles distant across the divide, and having also benefited occasionally by the visits of the School nurse and enjoyed the classes which the School’s extension worker held in their community, asked the heads of the Pine Mountain School to secure a trained…

[lin_frk_1924_004.jpg] – Page 4.

…teacher for their county school. A meeting was therefore held by the School’s extension worker to talk things over with the Line Fork people and it was agreed that the people should build a log house in which a teacher could live and that the School would procure a teacher, a nurse and a worker to hold Sunday School classes, cooking classes and to direct recreational activities.

The workers came shortly after this meeting and occupied temporarily a one-room, windowless cabin with a lean-to kitchen. Here they lived for several months until the new cabin could be built, cooking their meals over an open fireplace, and overcoming many difficult conditions—such, for instance, as fleas in profusion which the neighborly hogs, persistently continuing to sleep under their cabin floor, brought to them! The spacious new log house with its separate bed rooms, its comfortable and attractive living room and kitchen with a real “cook stove,” seemed a log cabin de luxe to the workers in comparison with their first home on the creek.

The Nurse and the Neighbors

The “fotched-on” teacher and the industrial worker, who was variously called “cook,” “house-keep,” “Sunday School tacher” or “singing tacher” needed, at the start, to interpret themselves, but they did not have to begin at the beginning as did the new nurse. Her relationship to her neighbors was not clear. Their idea of a nurse was a person from among their own number who came to stay during illness not only to care for the sick but also to perform any other duties that presented themselves, all the way from milking the cow to doing the family washing. A few who in great emergency had braved the journey to a far-off hospital, or a few scattered families who had been assisted in time of serious illness or accident by the School nurse from over the divide, had a vague conception of the trained bedside worker, but the real purpose and function of a public health nurse was absolutely unknown. Hence the nurse had to lay foundations for her work in an almost untouched and uncultivated field.

Her activities were in the beginning necessarily unorganized. She first had to visit in the homes merely as a neighbor and friend, but frequently such visits, ostensibly made in regard to some community activity, proved to be opportunities for real child-welfare or instructive nursing visits. Calls made by the people at the Settlement House were also used as an opening wedge to discuss personal and community health problems. The working of the neighbor children on the Settlement reservation at washing dishes and other household chores, the carrying and stacking of wood, and the keeping of the barn in good condition, proved to be excellent opportunities for the nurse to start health thinking in the individual children who did the work. The young ones could not help but observe that while “the women” of the cabin lived in the same type of house in which they lived, there was a difference; and by teaching them better ways of doing simple tasks, new standards of domestic and æsthetic values were opened to them.

The Nurse Gains Favor

As she persistently followed these various leads that interpreted her possibilities even in the least ways, it slowly began to dawn on the people how and when a nurse “from the outside” could be useful to them. That she herself could work, which to them meant keeping house, cooking, caring for a horse, and so forth, only increased her value, making them more open to the suggestions she frequently made regarding current community and personal health questions.

After proving herself, as it were, in the community, and having gotten acquainted with a large number of the children in their homes and at the settlement, the nurse decided in the fall of 1921 to carry out a health program in the schools. Although she realized that direct health talking as such would not get very far, inasmuch as there was no county organization to back her nor any local “diplomy” doctors to co-operate, a definite program for school work was outlined. The natives had profound respect for the Bible, accepting it as absolute authority on every subject. The children were play-hungry. The nurse therefore took these two things into consideration and decided to combine, as the basis for her health teaching, some….

[lin_frk_1924_005.jpg] – Page 5.

…of the Mosaic health laws of the Old Testament and those health principles then current in the community which seemed sound, with the material of the Child Health Organization.

So the health laws of the Old Testament were interpreted; health stories were told and enjoyed on their face value; health games were taught for the pure joy of them; but always with their underlying ideas of positive health backed up by simple demonstrations of the most fundamental health principles. There were exhibitions of how to wash one’s hands properly before eating, how one should wash one’s hair and what one should do to keep the head free of “lice,” and as the children swung into the spirit of their new game, they clamored to be the subjects for these demonstrations. The custom of taking coffee as the morning beverage was soon banished by a large number of children and that of drinking diluted and sweetened “corn liquor” began to be frowned on.

Shaved Dogwood Sticks for Tooth Brushes

The monthly weighing of the children soon became an event. This was done for the most part on the scales belonging to the store or post office nearest the school, for the transportation of the nurse’s so called “transportable scales” depended upon procuring two boys or men to carry them the necessary miles, since it was impossible for the nurse to carry them in her saddle-bags. The tooth brush drills were a real innovation, most of the parents never having possessed a tooth brush in their whole lives. It was not possible in all cases to make them see that such an article might prove an asset to their offspring, so in many instances teeth were still brushed with shaved dogwood sticks.

It was soon obvious to the nurse that physical examinations could not be conducted off-hand in these mountain schools, so they were not undertaken until, toward the end of the first year when the children and parents seemed prepared for it, a doctor from across the mountain was procured to come to the two Schools nearest the Settlement. Following these examinations a few cases of actual trachoma and some suspicious cases among the school children were treated regularly, and about twenty-five percent of the children needing remedial work were operated upon at the eye, ear, nose, and throat clinic held at the Pine Mountain School the following fall (1922).

Work of this character was conducted more or less in seven schools within a radius of ten miles of the Settlement, the most intensive work, of course, being done in the two schools nearest the Settlement where it was possible to get cooperation from the “outside” teachers who lived there.

“Raisin’ Up” the Health House

As demands upon the nurse increased it became evident that a “work-shop” other than the small supply closet in her own room at the Settlement cabin was necessary. So a meeting of the representative men of the community was held at which the nurse explained the necessity for a small “Health House” that could serve as an office and dispensary and a place where clinics and classes could be held. That a place larger than the workers already possessed could be necessary was beyond their comprehension at first. “Wasn’t six rooms enough?” they said. Or, “If it was a regular hospital” the nurse was “a wanting to raise up,” they could understand how such a place would be a “ben-e-fit”; but couldn’t “the big house with no beds in hit” (the unfamiliar living room of the Settlement cabin) be used for the classes and clinics the nurse was “a-talkin’ about?” All of which was a natural attitude for, as one of the men said, “nary a one” of those present had more than “four houses” (meaning four rooms) and that many only when there was “a great gang of young’uns” and the owner unusually prosperous.

The Whole Community Helps

Slowly and more carefully the reasons why a new building was essential if the work was to be carried on and why the living room of the Settlement cabin could not be used were again gone over, after which it was generally agreed by the men present that the nurse perhaps knew better than they. Pledges were then made to give timber and labor for its erection, and the next few weeks were taken up with the minute details of getting the pledges carried out. Every pledge made was fulfilled, but only after much tactful urging and reminding, a process always…

[lin_frk_1924_006.jpg] – Page 6.

…necessary to meet the typically mountain trait of “putting off” things although the intention to do them sooner or later is present.

Men set to the work of cutting trees, “snaking” the logs to the saw mill, sawing them into lumber and hauling the lumber to the new “house-seat.” This having been accomplished, a day was set for the “house raisin’,” and the day being fine, many “hands” appeared. After the “raisin’ ” there was a “workin’ ” each week when the men of the community gathered and gradually completed the house.

The Coming of the Dentists

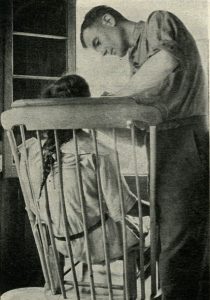

“THE HOMEMADE DENTAL CHAIR,” “In the Line Fork Country” by Anne Ruth Medcalf, American Child Health Magazine, Dec. 1924, p. 510.

Seven months elapsed from the first meeting of the men to the completion of the Health House, when it was possible to have baby clinics “babies’ and mothers’ parties” as they are called in these parts—and Little Mothers’ and Nursing classes at the head of Line Fork. The following fall a tonsil, adenoid and trachoma clinic was held in the Health House by the Kentucky State Board of Health, and during the past summer friends of the Settlement made arrangements for two dentists to come from Pittsburgh Health, and during the past summer friends of the Settlement made arrangements for two dentists to come from Pittsburgh for two weeks. The people swarmed to the Settlement from far and near— across mountains, ridges, divides and through creek beds— for what was in most cases the very first dental work they had ever had done by real “tooth-dentists.” Many had to be turned away for the dentists could do only what was physically possible. As it was they worked from dawn to dark, and accomplished a tremendous amount of work in spite of working quarters which must have seemed far from convenient in comparison to their well-equipped city offices, a changed environment and diet, baths in the creek and battles with the fleas and the chiggers!

“Victuals for the Young ‘uns in School”

“THE DENTISTS CROSSING PINE MOUNTAIN” — “In the Line Fork Country” by Anne Ruth Medcalf, American Child Health Magazine, Dec. 1924, p. 511.

Among other outside projects promoted and carried out the past year by the nurse none was more far reaching in its effects than the hot school lunches in the two schools nearest the Settlement. Two years were necessary to work up to them, during which time much talking was done by the teachers and the nurse to stimulate the interest of the parents and children in such an undertaking. In one of the schools a health pageant was given by the children and the teacher in order to gain the co-operation of the parents. It was very difficult to make the parents realize the benefits of a hot school lunch because of their narrow experience and limited outlook, but the children were for the most part eager to co-operate. Such objections as “we never had no sech like when we went to school;” and one father saying that he had always given his “young’uns all the victuals they needed and he reckoned he could keep on doing so,”—and other similar remonstrances had to be overcome. But after much discussing and explaining of the reasons for promoting hot school lunches and the benefits that could be derived from them, the parents were more or less won over and agreed to do what they could to make the project a going proposition.

Twenty dollars was given by an interested group of outside people to get the simple but necessary equipment to care for the 48 pupils in the two schools. This equipment, bought at wholesale, consisted of large aluminum cups, white metal teaspoons, four dishpans, two large kettles, two big cooking spoons, two paring…

[lin_frk_1924_007.jpg] – Page 7

…knives, and two small two-burner oil stoves that “did not need wood to make them go.” In both schools the girls made covers for the desks, napkins, dish cloths and towels from flour “pokes” (bags) which they brought from home. Large curtains were also made to partition the kitchen from the main schoolroom. The boys put up poles for the curtains and made shelves and tables from packing boxes. With this equipment gathered together and made ready for use, the problem of getting supplies was then discussed by the children, the teachers and the nurse, most of the parents already having agreed to do what they could. Some of the children agreed to bring potatoes, some milk, some sugar, others home-made soap or coal oil for the “wonderful new stove.” The teacher in each school supplied the cocoa as her share. A plan for alternating was also agreed upon to make the contributions for the families vary each week.

Learning to Like New Foods

The organization of the children for doing the actual work on the lunch was planned by the nurse and the respective teacher of each school, the nurse spending about a week in each. It was arranged that as many children as possible should take part in the preparations and care was taken that no child would be away from the schoolroom work too long. Just as things seemed to be going smoothly, however, an almost insurmountable difficulty presented itself. The children had never tasted the nutritious creamed soups and the cocoa which they were being taught to make; they were entirely unaccustomed to this greaseless food and they did not refrain from expressing their distaste for it; so how to get them to “down the stuff,” as they said, was the question. They were reminded that the food was well prepared and nutritious; they were challenged to be good sports instead of quitters; and they were promised that, if at the end of one week of honest trying to like the lunches they could not “down them,” then they need not try anymore. The arguments prevailed and the week of honest effort ended in the children genuinely relishing the luncheon dishes-—so much so that soon the family pails of corn bread and beans were left at home altogether. Cornbread alone was then brought to supplement the hot dish served at school.

The influence of the school lunches has been felt beyond the confines of the schools in which they operated. Many of the parents and relatives “stopped by” to see how they were worked, and the visitors were served on each occasion by the children in the same manner as themselves. Thus the value of the school lunch project was brought to the community at large.

Definite progress has been made by the health work in this section. Some of the people have been awakened from the one-time complete unconsciousness of their needs, a newer attitude is now developing toward preventive health measures, and some of the children have been affected by the positive health teaching as well as by the remedial health work which has been done in the schools.

The hope of the future lies in the proper training of the young, but the carrying out of a health program by such isolated units as Line Fork Settlement, while bettering in a degree local conditions, does not entirely cope with the general situation. Adequate care cannot be taken of these situations until the county and state assume the responsibility of the education and leadership of the people in these Southern Highlands. When this is done the people will shoulder their own responsibilities as they always have in the past according to their knowledge.

GALLERY: Anne Ruth Medcalf “In the Line Fork Country,” 1924

Medcalf, Ann Ruth. “In the Line Fork Country.” American Child Health Magazine, December 1924, pp. 505-511.

- Anne Ruth Medcalf – “In the Line Fork Country,” American Child Health Magazine, December 1924. p. 1. [lin_frk_1924_001.jpg]

- Magazine article: Anne Ruth Medcalf – “In the Line Fork Country,” American Child Health Magazine, December 1924. p. 2. [lin_frk_1924_002.jpg]

- Anne Medcalf – “In the Line Fork Country” American Child Health Magazine, December 1924. p. 3. [lin_frk_1924_003.jpg]

- Anne Medcalf – “In the Line Fork Country” American Child Health Magazine, December 1924. p. 4. [lin_frk_1924_004.jpg]

- Anne Medcalf – “In the Line Fork Country” American Child Health Magazine, December 1924. p. 5. [lin_frk_1924_005.jpg]

- Anne Medcalf – “In the Line Fork Country” American Child Health Magazine, December 1924. p. 6. [lin_frk_1924_006.jpg]

- Anne Medcalf – “In the Line Fork Country” American Child Health Magazine, December 1924. p. 7. [lin_frk_1924_007.jpg]

SEE ALSO:

ANNE RUTH MEDCALF Correspondence I 1921-1922

ANNE RUTH MEDCALF Correspondence II 1923-1924

ANNE RUTH MEDCALF Line Fork Settlement Report n.d.

ANNE RUTH MEDCALF Report to Miss Pettit 11 Feb 1922

ANNE RUTH MEDCALF Staff Biography

RETURN TO:

LINE FORK SETTLEMENT WORKERS Reports Publications Guide 1921-1941