Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 13: EDUCATION

Series 21: RURAL YOUTH GUIDANCE INSTITUTES

1937 Findings

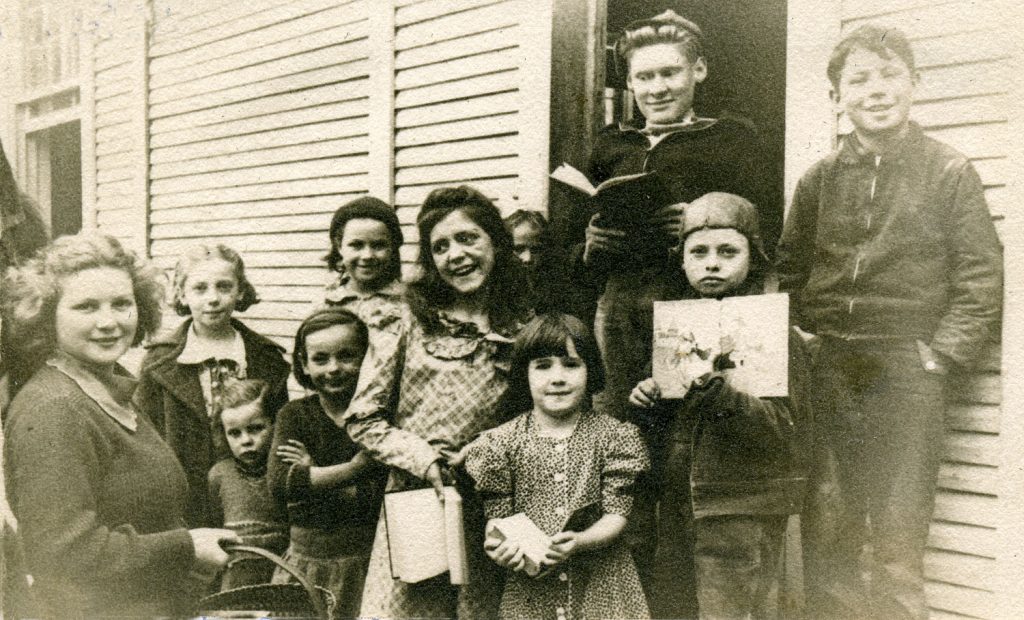

06_2443 PMSS students. Nan Milan, far left, c. 1937. [098_IX_students_06_2443004.jpg]

RURAL YOUTH GUIDANCE INSTITUTE 1937 Findings

TAGS: Rural Youth Guidance Institute 1937 Findings, youth leaders, Alliance for Guidance of Rural Youth, rural youth needs, vocational counseling, vocational education, guidance programs, youth migration to city, agriculture as a vocation, CCC camps, U.S. Employment Service, Homeplace, 4-H Clubs, George-Deen Act

The cover of the RURAL YOUTH GUIDANCE INSTITUTE 1937 FINDINGS indicates that this convention of youth leaders was sponsored by the Alliance for Guidance of Rural Youth (formerly, the Southern Woman’s Educational Alliance) with the cooperation of other agencies and individual consultants. It was held on November 1-3, 1937, at the Mayflower Hotel located in Washington, DC.

CONTENTS: Rural Youth Guidance Institute 1937 Findings ; consultants ; Alliance for Guidance of Rural Youth ; rural youth needs ; vocational counseling ; vocational education ; youth-serving agencies ; guidance programs ; youth migration to city ; agriculture as a vocation ; CCC camps ; rural non-farm opportunities ; U.S. Employment Service ; NYA ; training for rural living ; Homeplace ; 4-H Clubs ; teacher-training ; George-Deen Act ; itinerant counselors ; experimental regional vocational schools ; out-of-school youth ; handicapped children ; credit unions ; birth control ; regional occupational schools ; case studies ; homemaking education ; education of parents ;

TRANSCRIPTION: RURAL YOUTH GUIDANCE INSTITUTE 1937 Findings

[1937_findings_rural_youth_cover.jpg]

FINDINGS OF THE RURAL YOUTH GUIDANCE INSTITUTE

Sponsored by

The Alliance for Guidance of Rural Youth

(Formerly the Southern Woman’s Educational Alliance)

With the Cooperation of Other Agencies and Individual Consultants

Washington, D.C., Mayflower Hotel

November 1-3, 1937

Alliance for Guidance of Rural Youth

401-02 Grace-American Building

Richmond, Virginia

[1937_findings_rural_youth_consult1.jpg]

CONSULTANTS

Cornelia S. Adair, Member, Educational Policies Committee, National Education Association

Wallace Ashby, Chief, Division of Structures, Bureau of Agricultural Engineering, U. S. Dept. of Agriculture

Alice M. Baldwin, Dean of Women, Duke University

T. G. Bennett, Educational Adviser, Third Corps Area, United States Army

Geline MacD. Bowman, Past President and Honorary President, National Federation of Business and Professional Women’s Clubs

Arthur L. Brandon, Executive Assistant, American Youth Commission, American Council on Education

Anna L. Burdick, Special Agent, Women and Girls, Trade and Industrial Education Service, U. S. Office of Education

Walter Burr, Associate Director, U. S. Employment Service, U. S. Department of Labor

Susan M. Burson, Agent for Special Groups, Home Economics Education Service, U. S. Office of Education

Annie M. Cherry, Director, Spring Hope (N.C.) Educational Experiment, General Education Board and Columbia University

John Conley, Assistant to Walter Burr, Associate Director, U. S. Employment Service

Katherine M. Cook, Chief of Special Problems, U. S. Office of Education

Mabel C. Costigan, Administrative Assistant, National Youth Administration

Martha G. Creighton, Supervisor of Home Economics Education, Virginia State Board of Education

Howard A. Dawson, Director of Rural Service, National Education Association

David C. Donoho, Artist and Art Instructor, Breathitt Co. (Ky.) School System

Arthur H. Estabrook, formerly of Carnegie Institution of Washington

Florence Fallgatter, Chief, Home Economics Education Service, U. S. Office of Education

Harry R. Fulton, Adviser to Bacon Follow Community House and Wyatt School in Greene County, Va.

R. W. Gregory, Specialist in Part-Time and Evening Schools, Agricultural Education Service, U. S. Office of Education

Lula M. Hale, Head of Homeplace, Perry County, Kentucky

Margaret J. Hoff, Director, Cumberland Mountain Mission, Scott Co., Va.

Kathryn McHale, General Director, American Association of University Women

[1937_findings_rural_youth_consult2.jpg]

Jessie M. Robbins, National Education Association, Rural Department

John A. Lang, CCC Administrative Assistant, U. S. Office of Education

Ata Lee, State Supervisor of Home Economics Education, Kentucky

John A. Linke, Chief, Agricultural Education Service, U.S. Office of Education

Helen H. Little, Counselor, Breathitt High School, Breathitt County, Ky.

Theodore B. Manny, In Charge Dept. of Sociology, University of Maryland

Bruce L. Melvin, Principal Research Supervisor, Works Progress Administration

Eugene Merritt, Senior Extension Economist, Extension Service, U. S. Department of Agriculture

E. C. L. Miller, Librarian, Medical College of Virginia, and Secretary, Virginia Academy of Science

Nora Miller, Home Demonstration Agent, Virginia Agricultural and Home Economics Extension Service

Glyn A. Morris, Director, Pine Mountain Settlement School, Harlan Co., Ky.

C. R. Orchard, Director, Credit Union Div., Farm Credit Administration

Edward W. Oxley, Director, CCC Camp Education, U. S. Office of Education

Hattie S. Parrott, Division of Instructional Service, North Carolina State Department of Education

Ruby Ruebush, In Charge of Bacon Hollow Community House and Wyatt School in Greene Co., Va.

Elna N. Smith, Associate Research Supervisor, Works Progress Administration

Louise Stanley, Chief, Bureau of Home Economics, U.S. Department of Agriculture

Marie R. Turner, Superintendent of Schools, Breathitt County, Ky.

Ada E. Valentine, Local Director, Spring Hope (N.C.) Educational Experiment

Iris Calderhead Walker, Consumers’ Counsel Division, AAA, U.S. Department of Agriculture

Gertrude L. Warren, Organization, 4-H Club Work, Division of Cooperative Extension, U.S. Department of Agriculture

Esther Weller, Pine Mountain Settlement School, Harlan Co., Ky.

Edwin E. White, Pastor, Pleasant Hill (Tenn.) Community Church

Otto Wilson, Credit Union Division, Farm Credit Administration

Among a number of guests who attended one session of the Institute were Aubrey Williams, Director of the National Youth Administration and Dr. L. R. Alderman, Director of Adult Education under WPA.

[1937_findings_rural_youth_001.jpg]

FINDINGS OF THE RURAL YOUTH GUIDANCE INSTITUTE

Sponsored by

The Alliance for Guidance of Rural Youth

(Formerly the Southern Woman’s Educational Alliance)

With the Cooperation of Other Agencies and Individual Consultants

Washington, D. C., Mayflower Hotel

November 1–3, 1937

The Institute was organized around the problems faced by rural youth today in the need for counseling, for information about rural occupations, for better vocational education opportunities, and for rural placement services of a guidance grounded sort. The discussions polarized about the inadequacies and difficulties of youth-serving agencies now working in the field to meet these problems, and about ways of instituting remedial measures.

Throughout the discussion, the need of preparing professional and other rural leaders to function adequately in a guidance program recurred persistently, eventuating in several recommendations.

I. THE PROBLEM STATED

The difficulties of rural youth in finding its way without the needed guidance aids were first presented by rural leaders in terms of individual young people whose problems symbolize those of many others. In mountains and in other rural areas of restricted opportunities, vast numbers of youth have, during the last few years, found it impossible to locate themselves vocationally and have faced serious predicaments, wandering from place to place, unable to assume responsibility either for themselves or for their own families, often remaining either wholly or partially dependent upon them. However, these unfortunate instances, although appearing to “pile-up” during the depression years, were, in reality, the result of long-time trends.

[1937_findings_rural_youth_002.jpg]

-2-

From 1930 to 1935 the net migration of youth from the country to the city probably did not exceed 200,000, thus leaving about a million more on the farm than would have been there, had the migration flow continued in those five years as during the preceding ten. It is also known that the farms today have two million more youth than are needed to grow the commercial agricultural products. It is obvious from these facts that agriculture, as a vocation, can often be greatly overstressed. It has been estimated that in 1935 there were almost 10,000,000 rural youth of whom over three-fifths were farm and the remainder, rural non-farm youth. It is probable that from 75 to 80 per cent of these rural youth were out of school. Furthermore, most of them lacked vocational training unless they had taken vocational agriculture or attended CCC camps.

Some of these youth might be absorbed in rural non-farm occupations, although the extent to which this is practical has not been explored, great as is the need for doing so. Information on rural non-farm opportunities is severely lacking.

II. YOUTH-SERVING AGENCIES IN THE FIELD

A number of agencies are working with youth in educational and other fields but, on the whole, their programs are inadequate for serving rural communities. Some governmental agencies which, in one way or another, assist rural youth are the NYA, WPA, CCC, U.S. Employment Service, Cooperative Agricultural Extension Service, 4-H Clubs, U.S. Public Health Service, Office of Education, Children’s Bureau, Farm Security Administration, Social Security, and the Farm Credit Administration. In addition several agencies outside the government concern themselves with the problems of youth, such as the American Youth Commission, the American Farm Federation Bureau, the American Vocational Association, the National Education Association, and so on. But with all the rural activities which are being promoted through these channels, youth in rural areas are not being assisted to find an occupation as are urban youth.

[1937_findings_rural_youth_003.jpg]

-3

The Need for Information About Occupations

Patches of progress are being made here and there in collecting data on the rural non-farm occupations. For example, Dr. Arthur K. Getman of the New York State Board of Education has brought together useful information about local opportunities and is correlating this with provision for training. Also, in some CCC camps, care is being taken to train boys for occupational opportunities back in their home communities. It should be actively recognized, however, that information about occupational opportunities, other than farming, in rural territory is disastrously lacking, and that, as a result, large proportions of rural youth are drifting blindly into unprofitable agriculture, or into the cities without training and without other assets needed for adjustment there. To date none of the above mentioned agencies have been able to supply the needed occupational information.

The Need for Vocational Counseling and Training

Moreover, rural young people very rarely have vocational counseling to assist them in choosing wisely among such occupations as are known to exist. Nor are facilities available for them to secure adequate occupational training, since in rural territory the training is largely in terms of agriculture, and comparatively few of the grand total who enter school have either agricultural training or counseling about agriculture, whereas training in trades and even in home maintenance industries is almost wholly neglected; and, although home economics has been finding its way into many rural high schools and this training is to be commended and needs extension, it is not designed for vocational activities.

The U.S. Employment Service

The inadequacy of the Placement Service of the U.S. Employment Service for rural youth was emphasized both because the offices of this agency are often inaccessible to many of them and because counseling service for juniors, which…

[1937_findings_rural_youth_004.jpg]

-4-

…has been provided in 61 cities, through the cooperation of the NYA, has not been extended to rural communities. although equally needed in rural areas, it functions only for city youth.

The NYA

Not only in its student aid, but in its work projects as well, the NYA is being forced to restrict its program although both are providing practical training. However, its work has never been adequate in the more maladjusted areas and with the restriction of activities, larger and larger numbers of youth will be handicapped because of lack of opportunity. For example, in Breathitt County, Kentucky, some 200 rural youth had applied for aid in high school, but only 60 received help. The remainder could not attend. Likewise, there were only about 100 young people on the NYA projects there, although from 500 to 700 needed such work and training as the NYA afforded. In a county now coming to be so alive educationally and yet one so largely dependent upon its county high school to provide future leaders, the loss is serious indeed.

The CCC Camps

Although the CCC camps are operating on a counseling basis and are providing helpful types of training for the increasing number of young men being accepted, there are naturally very large numbers who are not being reached by them, and no claim is made that they are suited to all older youth needing adjustment.

III. NEED FOR ACTION

Since the pressing need for better rural opportunities for youth was established and since it was also shown that agencies operating in rural territories are now unable to perform the needed services, it was felt that constructive programs should be worked out and that among the various governmental and non-governmental agencies now operating, were to be found methods and possibilities which, if properly adjusted and expanded, might go a long way toward meeting the needs, although represen-…

[1937_findings_rural_youth_005.jpg]

-5-

…tatives of various agencies indicated the danger of the increasing restriction of their activities. Attention was called also to the need for more coordination among existing agencies and suggestions looking toward more constructive action were made.

Training for Rural Living

It was strongly felt too, that since a majority of rural youth seem likely to have to remain in rural territory, even though not needed in agriculture, and since the increase of governmental personnel or outside funds for assisting local communities is uncertain, every available facility within and without rural communities needs to be utilized to improve existing conditions, even those obtaining in the most adverse environment. In conformity with this necessity, it was the sense of the Institute that much of the educational program for rural youth should be centered upon improving home life and environmental conditions in communities or neighborhoods, although this should be done always with due consideration of the guidance needed by those who must or will go out. Such a program should feature opportunities for instruction in the practical and useful arts of homemaking, agriculture and also in those basic mechanical and industrial processes necessary for meeting the fundamental needs of any community. These should be available for all at a sufficiently early school level to afford the youth as wide a range as possible of experience from which a choice of work or further training may be made, whether the individual boy or girl involved goes or stays.

It was felt that more vocational home economics and 4-H Club services are needed in impoverished, isolated areas, in order to prepare more adequately for living, the young people most apt to remain on the elementary school level. Such services were felt to be especially needed because both incorporate the basic principles of training for living in rural territories. A striking demonstration of meeting this need was recognized as taking place in the work of home economics teachers going out from Homeplace, in mountainous Perry County in Kentucky, for…

[1937_findings_rural_youth_006.jpg]

-6-

…supplementing the work of elementary schools by teaching cooking in kitchens of homes adjoining the schools, both in that county and in an adjoining one. Such a demonstration was recognized by the vocational home economics section of the Institute as pointing the way valuably, and plans were laid for further experimentation along such lines in another area, through cooperation of state and county agencies. The 4-H Club leaders are engaged at present on studies of the older out-of-school youth which include those on this level, as well as on higher ones, and should yield invaluable light on other ways of meeting their needs.

Provision for Counseling

The members of the Institute were of the opinion that application should be made to federal authorities for provision of additional counseling service in rural areas, as well as for more diversified and better adjusted forms of vocational education. It was thought possible for this provision to be made under the present category of teacher-training now set up in the George-Deen Act, and it was proposed that, within some reasonable geographical unit, presumably regulated by ease in transportation, an itinerant counselor should visit public schools, CCC camps, NYA project leaders and possibly those of other youth serving agencies, for giving instruction to teachers, foremen, and other youth leaders, as to the simpler techniques of guidance and in their direct application.

It was pointed out too, that, if any regional vocational schools should be established, they might well include in their functions the training of individual counselors and of vocational guidance specialists to prepare workers to function in a guidance program needed in these rural communities.

[1937_findings_rural_youth_007.jpg]

-7-

More Adequate Opportunities for Vocational Education

It was the sense of the Institute that more diverse and better adjusted types of vocational training should be spread in high schools with special but not exclusive reference to local and regional absorption of young people so trained. The creation of one or more experimental regional vocational schools to serve h.s. graduates and other selected students drawn from a wide regional area seemed to win general approval, although not intensively discussed. It was urged too, that vocational training be given to out-of-school youth, whether on relief or not, with practice procurable through work projects such as those now carried on by the NYA and WPA and by other suitable and properly cooperating agencies.

Proper Guidance will Necessitate Curriculum Changes

It was recognized that guidance in its concern for individual problems and adjustments must inevitably bring about basic curriculum changes where traditional methods and subject matter still hold sway. The program at Spring Hope, N.C., was cited as one of outstanding excellence in the practical guidance and help being given handicapped children on the elementary school level.

Occupational Aids Approved

Citizens’ Service Exchange Methods. It is hoped that the program of work and the method used by the Citizens’ Service Exchange of Richmond, in meeting the needs of the relief and unemployed population of the city, may have in its philosophy and experience a method adaptable to the creation of occupation and work opportunities in rural areas. This Exchange provides different types of work against which scrip is issued, and used to buy goods produced by the Exchange. It was suggested that, especially in super-rural areas, different kinds of goods might be made and exchanged among those who would mutually profit by this arrangement.

[1937_findings_rural_youth_008.jpg]

–8–

Credit Unions. Credit unions were considered favorably as representing a method of saving and borrowing on the part of people with exceedingly low incomes and an agency readily adaptable to instituting long-time programs in saving and borrowing as well as in education in saving. The successful credit union in operation at Brasstown, N.C., suggests that the plan may be adaptable to other mountain areas, and steps were taken during the conference looking toward similar experimentation elsewhere in a more or less similar area.

Birth Control. Although it was recognized that birth control cannot be considered a cure-all in over-populated areas, and that spread of education will itself do much to promote it, its importance in a preventive program was felt by many, especially among the rural leaders themselves.

Junior Placement. The suggestion was favorably received that state employment offices, acting in cooperation with the USES [U.S. Employment Service], be asked to send properly qualified interviewers to rural county seats, to inform and counsel rural young people about both rural and urban occupations and to register and otherwise assist those ready for employment. It was suggested that the NYA and the U.S. Employment Service be asked to extend their counseling and placement services into rural areas.

Experimentation Needed in Vocational Adjustment of Older Youth

In order that more adequate ways of coping with the problems of vocational adjustments among youth may be devised, it is the desire of the Institute to see one or more experiments instituted among young people in the more maladjusted areas. Such experimentation might be fostered by placing one or more counselors, within one or more selected counties, to work with the various agencies there having or capable of having specific functions helpful in the promotion of youth adjustment whether the young people are needed to make contacts in or outside their communities. It is hoped that funds may be secured from sources outside of the government for the carrying out of such an experiment or experiments, although…

[1937_findings_rural_youth_009.jpg]

-9-

…governmental experiments in rural areas, comparable to many being fostered in cities, are needed. A few other features of such an experiment could well be:-

1. A County Planning Board or Council as a coordinating agency for the undertaking, with all appropriate agencies represented on it or cooperating in it.

2. Stimulation of provision of information about rural occupations by the U. S. and States’ Employment Services, and dissemination of it within the county.

3. Facilities for counseling youth respecting their vocational needs and possibilities, and also, as to plans, ways and means of securing training for meeting these possibilities, and so on.

4. Stimulation of the organization of rural youth groups or forums for discussion among themselves of the problems of youth and of other vital subjects.

SUPPLEMENTARY FACTS AND COMMENTS

To the above findings of the Institute Committee, the Alliance for Guidance of Rural Youth adds a few facts and comments, from the perspective of an agency primarily concerned with the orientation of rural youth.

Nobody can intelligently doubt that many people, including an increasing number of old people, will continue to live in rural areas or that the maintenance and improvement of rural life [are] basic to national welfare. But in vast stretches of rural territory youth of the better sort need more incentives for staying and for improving conditions. Moreover, Secretary Wallace’s recent statement that it will not be long before three-fourths of our rural born population will be living in cities, itself climaxes other explanation as to the necessity for provision in rural areas for training in non-agricultural occupations as well as in agricultural ones.

In relation to agriculture as an occupation, this new emphasis by the U. S. Department of Agriculture comes to light strongly in the following summary of statements by Eugene Merritt, Senior Extension Economist of the Division of Cooperative Extension. *If present living standards are raised or even maintained:

50% of present farm youth must become entirely dependent upon a non-agricultural occupation.

25% of the others must find part time non-agricultural jobs.

The remaining 25% may find farm resources for a fairly adequate living.

*These statements were made by Mr. Merritt in Circular 264, May 1937, and others, and frequently quoted in other reports issued by this Division.

[1937_findings_rural_youth_010.jpg]

-10-

This conclusion itself compels others and Mr. Merritt has added several in pointing out that information about non-agricultural occupations, counseling in regard to occupations, and the acquirement of skills in wisely chosen occupations is needed by three fourths of our farm youth. Meanwhile, approximately four million non-farm youth, not noted in the above generalizations, naturally provide still larger proportions of need for such help.

On the other hand, it is significant that the Institute and the reports presented at the Land Grant Colleges’ conference both stressed the need for more widespread instruction in basic agricultural skills. The latter stressed also, the need for much research to give light on the pros and cons of agriculture as an occupation, and to discover more effectively what types of young people can enter it to the best advantage. Following this thought, the Agricultural Extension Committee urged exploration of how young people of the next generation can make a living and with it a happy rural life, especially if all present trends in agriculture are to be faced.

In keeping with this general inquiry, one of the strong pre-occupations of the Institute was that of the importance of enriching elementary school facilities and other early offerings so as to anticipate and reduce the present vast problem of older rural youth unprepared and adrift. Under present conditions, a large proportion of the scanty youth service extended in rural areas is reminiscent of locking the stable after the horse is stolen. Many suggestions, including especially those advocating itinerant instructors and counselors, resulted from this realization.

One of several gratifying features of the discussion was the marked advance in acceptance by youth leaders of the modern concept of guidance as basic to its best service for youth. This in turn is naturally leading to the increased acceptance of the importance of preparing, both in pre-service training and on the job, for rendering guidance service. The itinerant instructor in guidance, guidance institutes and provision of institutional training in guidance for rural youth leaders were approved for accomplishing this means.

There was much insistence, too, upon the need for changes that would make such training opportunities, as are now provided for rural youth, more effective by making them more flexible and more functional in relation to regional conditions. This emphasis led on from the elementary school through the high school to advocacy of regional occupational schools which, on the basis of all needed fact-finding, should provide training of widely constructive significance to the area, as well as to city bound youth, and so, to society in general.

The need for closer coordination of services of youth agencies functioning in rural areas was frequently discussed, although more time could well have been spent, had it been available, upon this discussion. This applies both to governmental agencies and to others and is especially pertinent in view of lessening appropriations and increasing youth needs. However, it was hoped that experimentation already getting underway in a few places in the needed coordination of effort would be expanded and that similar experimentations could be launched increasingly in other counties and regions. This is of almost supreme importance both for the most efficient technique and because funds for the needed rural services are at best so inadequate that all possible unifying of effort is needed for stretching them to the utmost.

[1937_findings_rural_youth_011.jpg]

–11-

REPORT OF COMMITTEE ON

PROBLEMS IN RURAL YOUTH OPPORTUNITIES

I. Need of Information About Rural Occupations:

Case A – A Kentucky girl, 20 years of age, high school graduate, with some clerical store experience, desires to know what occupational opportunities there are for her in her Kentucky community. She is unable to obtain such information and is now drifting.

Case B – A North Carolina high school graduate desires college education: he is without funds or financial contacts, must earn his own way through college; therefore, is looking for employment to enable him to attend college.

II. Vocational Counseling:

Case A – A North Carolina farm boy had failed in his academic work consistently, was growing restless in school stalemate, showed considerable ability in scout work and had good personality traits, wanted advisory service on the type of work which he could enter that would suit his interests and abilities and afford him and his family livelihood; he showed particular interest in highway safety, patrol work, and related employment. Wanted guidance on how to enter this occupational field or kindred ones.

Case B – A Virginia lad with much interest in mechanical activities and with energy and ambition found his school training uninteresting and unattractive; he particularly wanted to know what devices “back of the typewriter made it tick”; desired guidance and training in mechanical fields but was unable to secure such an opportunity; attempted through local opportunities to realize his desires but continued to find a lack of vocational guidance and training.

Case C – A North Carolina girl desired to become a nurse, found that her high school preparation was inadequate; entered nurse training course but found that she couldn’t carry the work, went back to her high school for guidance and further training to enable her to take up nurse training according to requirements; when questioned on why she failed in advanced training, she admitted that no one in the school had counseled her on the requirements involved in nursing.

III. Vocational Education:

(1) In elementary schools:

Case A – Two Virginia girls, in elementary grades, possessing interest and aptitudes in rug making, canning, crocheting, and other arts and crafts, wanted elementary vocational training along these lines; needed to earn a part of their living from this source; were unable to obtain such vocational training in elementary grades. Although they were 15 and 16 years of age respectively, they were still in elementary grades, they had reached the point in life when they needed to earn a part of their living.

[1937_findings_rural_youth_012.jpg]

-12-

(2) In high schools:

Case 3 – A Kentucky high school junior wanted mechanical training, was not interested in literary or cultural course which was the only training available, grew restless and dissatisfied, dropped out of school, obtained work in coal mine but found that he was unable to secure related mechanical training and desired advancement, became discouraged with mining and dropped out, now drifting.

(3) Itinerant vocational instruction service:

Case C – A Virginia farm boy, 15 years of age, slightly crippled, was not attracted to regular school courses offered by local country school; wanted handicraft instruction but found that local school was unable to provide for this type of training. If the boy does not find instruction along the lines of his interests, he will probably become a dependent on his family or state.

IV. Rural Placement Service:

Case A – A Virginia girl, aged 16, has acquired some skill in typewriting, has interest in improving her knowledge of shorthand and typing, needs further training to hold regular stenographic work but is unable to secure it in home town; she wants part-time employment in community where she can get the stenographic training she desires. Believes that there should be some office work into which she could go as an initial step to toward stenographic employment.

Case B – A Breathitt County, Kentucky, high school graduate wants to enter the field of lunch room service, is willing to start at the bottom and work up to the position of owning a lunch room; in Breathitt County, the entrance to such a vocation is through domestic service which carries a stigma there; the girl wants opportunity to pursue chosen vocation in a nearby urban community which will enable her to progress in the field of commercial lunch room service.

V. Need for Training of Guidance Helpers:

Ada E. Valentine

John A. Lang, Chairman

[1937_findings_rural_youth_013.jpg] MISSING

[1937_findings_rural_youth_014.jpg]

-14-

REPORT OF COMMITTEE ON

HOME ECONOMICS SERVICE FOR RURAL GIRLS

1. Recognizing the need for training in homemaking for rural girls over 14 years of age, and realizing that if these girls are to be reached it must be in the elementary school, we recommend that the states investigate the possibility of developing vocational programs in homemaking for these girls.

One means of making such programs available would be the employment of an itinerant teacher who would serve neighboring rural school centers.

2. It is recommended that such itinerant teachers work with elementary teachers in rural schools in introducing home life activities in the educational program for all children.

3. It is also recommended that homemaking education should be included in the preparation of all elementary school teachers.

4. Recognizing the need for reaching out-of-school youth and adults, it is urged that school administrators provide time in the day school teacher’s schedule for contacting and teaching classes for these groups.

5. It is finally recommended that where vocational programs are organized in rural areas, they be planned in cooperation with existing agencies in order to coordinate all work that is directed toward education for home and family life, and thus make it more effective.

Susan M. Burson

Annie M. Cherry

Martha G. Creighton

Florence Fallgatter

Lula M. Hale

Margaret J. Hoff

Alta Lee

Glyn A. Morris

Louise Stanley

Gertrude L. Warren

Edwin E. White

Helen W. Atwater, as Editor of Journal of Home Economies

Alice M. Baldwin, Chairman

[1937_findings_rural_youth_015.jpg]

-15-

RΕPORT OF COMMITTEE ΟΝ

BASIC GUIDANCE NEEDS IN RURAL HIGH SCHOOLS

l. More removal of mechanical and physical difficulties to secondary education by consolidation in underprivileged, areas where practicable and more school transportation facilities.

2. Revamping of system of state and federal support in order to accomplish major objectives of education.

3. The educational program for the youth in rural areas should be centered upon home life and the environing conditions of the community or neighborhood. It should feature opportunities and facilities for instruction in the basic and fundamental skills of the practical and useful arts of homemaking, agriculture and such mechanical and industrial processes as are necessary to carry on the work in the village and on the farm, thereby affording a wide range of productive experiences through which an individual may discover his abilities and determine his choice of work or of further training.

4. Inauguration and maintenance of continuous study of rural occupational opportunities, with such information made available by federal and state agencies and made adjustable to local situations.

5. Recognition is due, also, of the need for development of new occupations and study of trends in occupations.

6. Not only broader vocational education opportunity but broader curriculum opportunities, in general, for adjustment to individual need, and for general enrichment of rural living, including also vocational education.

7. For the same purposes of individual need and also for general enrichment of rural living, much less formalized requirements and instruction procedures. To accomplish these aims, the average teacher-training needs a revamping of its philosophy and of its educational techniques.

Colleges need to recognize the desirability of flexible, individualized high school programs and to accept students with a minimum of required subjects on the basis of recorded evidence as to individual abilities and achievements.

Parents need to be educated to a new point of view. This is obviously a community obligation but federal and state agencies can do much to promote public sentiment and public support for such programs.

8. Counseling is a vital necessity for rural youth as for urban, and requires special training. There is need for federal and state agencies to begin, on a large scale and in a thorough manner, to develop the training for needed counselors and to provide funds for employing counselors.

Alice M. Baldwin

Anna L. Burdick

Marie R., Turner

Glyn A. Morris, Chairman

GALLERY: RURAL YOUTH GUIDANCE INSTITUTE 1937 Findings

[NOTE: Page 13 missing in original stapled report.]

- 1937_findings_rural_youth_cover.jpg

- 1937_findings_rural_youth_consult1.jpg

- 1937_findings_rural_youth_consult2.jpg

- 1937_findings_rural_youth_001.jpg

- 1937_findings_rural_youth_002.jpg

- 1937_findings_rural_youth_003.jpg

- 1937_findings_rural_youth_004jpg

- 1937_findings_rural_youth_005jpg

- 1937_findings_rural_youth_006.jpg

- 1937_findings_rural_youth_007.jpg

- 1937_findings_rural_youth_008.jpg

- 1937_findings_rural_youth_009.jpg

- 1937_findings_rural_youth_010.jpg

- 1937_findings_rural_youth_011.jpg

- 1937_findings_rural_youth_012.jpg

- 1937_findings_rural_youth_014.jpg

- 1937_findings_rural_youth_015.jpg

See Also:

EDUCATION

Return To:

RYGI RURAL YOUTH GUIDANCE INSTITUTES Guide By Year, 1937-1963