Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 09: BIOGRAPHY Visitor

Series 13: EDUCATION

JUDITH FAY

Visiting Teacher

Whose comments were recorded and typed by

Alice Cobb

1937

Judith Fay and Vacation School at Little Laurel.

An experiment in “progressive education”

Planned and Conducted by

Judith Fay, an English visitor.

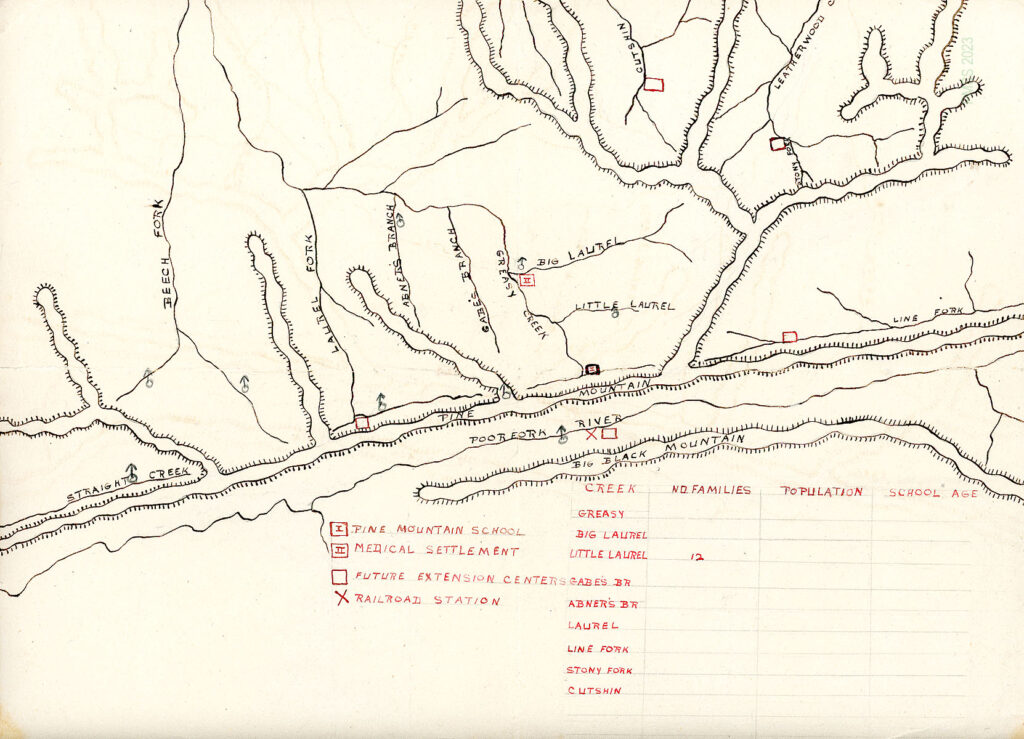

MAP of the North Side of Pine Mountain. 12 [fay_judith_vacation_sch_012]

JUDITH FAY Vacation School at Little Laurel: An Experiment in “Progressive Education” [Transcribed by Alice Cobb]

A very personal reflection by a transient British teacher of the Vacation School at Little Laurel in the Summer of 1937. Captured in a transcription by Alice Cobb, a Pine Mountain Settlement School employee, the report is not a reflection of Miss Cobb. The summer experiment, though carefully observed, is not objective and is based on Judith Faye’s expectations of the summer school group and her limited experience in the Appalachians. While it falls short of the professional objective, it provides a very intimate observation of the children in that short-term summer classroom. Personal bias mingles with a close observational and educational eye and the picture of the classroom is rendered in detail for others to evaluate — and enjoy.

p.1

VACATION SCHOOL AT LITTLE LAUREL

An Experiment in “Progressive Education”

Planned and conducted by Judith Fay, an English [from England] Visitor

[Alice Cobb recorded and transcribed Fay’s account of her work in the Community]

The idea of a vacation school at Little Laurel was discussed at Christmas by Alice Cobb, Miss [Edith] Cold, and Miss Fay. Com. [Commissioner] Oscar Begley, the trustee was approached in January. He agreed that a vacation school would be valuable, so long as good discipline were maintained. He also agreed to equip us with pupils and coal.

Vacation school was to start as soon as the official county school was out, about the second week in February. It was to be held every day from 1:30 to 4 in the one-room schoolhouse down the creek. The teacher planned to give the children what their ordinary curriculum most lacked, to include a great deal of active work, and to try and raise interest that might stay permanently with the children and give them something to do at home.

We started in on a Monday. The coal arrived at the schoolhouse five minutes before I did. The children, on the other hand, had been waiting several hours, both that Monday and the two preceding ones, owing to vagueness in the mind of the trustees. From the very first, scarcely anyone was shy, and everyone began to make himself quite at home in his own particular manner. Some play ball or run races. round the stove; some ate candy and chatted; some unpacked my supplies and discussed which things they had hoped to take home. Several older ones discussed the curriculum with me. They had heard that we were to learn cooking, clay modeling, and dancing. From the first they knew exactly what they wanted to do.

After two weeks, the numbers fell to 13. Two families living way up Little Laurel Branch stopped [coming] owing to work at home, snow, lack of shoes, a new baby and lack of enthusiasm. After that we kept at a steady 13. Four families were represented: O. B.’s four children: B. S.’s four children; D. M.’s four children; and D. C.,’s one child. Three out of four families were loyal to the school all along, [and] sent their children regularly and helped in many ways, such as lending brooms, etc., providing lunch for hikes; making cakes; allowing older children to help house clean on Saturday’s; and not making a fuss when children fell in the creek or arrived home covered with paint, glue, or clay. One parent, undergoing domestic difficulties, took it out on the school and kept the children at home for a while but, finally capitulated through a strong desire to borrow our Victrola. On the whole, the parents very sensibly took advantage of prolonged free education and a chance to get rid of small children for three hours a day.

The children ranged in age from 8 to 13 years. The youngest was T. S. (2). Oh, I think she got [the] most out of the Vacation School. She certainly enjoyed it the most and made life bad for her family when either she or I didn’t get to school. At first, she was quite babyish and expected to be carried around, and wouldn’t play or work on her own. The gift of some doll dishes and cutlery solved this, and for the remaining three months she was quite absorbed in elaborate housekeeping.

p. 2

She was a very special person and persistently joined in all games and dances and was most annoyed when she was not invited to do a 20 mile hike. ” I am coming, too, Miss Fay, ” she said. Mutinously, T.’s temper was always variable, but I think it improved as she found she could get things without lying in the road, yelling.

I think the most lively and most promising section of the school was a gang of six little boys. Our B. B., Bby, and J. S; H. M., and E. P. They rejoiced in terrific energy and productiveness. Our B. was a beautiful, sturdy, innocent-looking child (5). Used to come to school in a flowered satin waistcoat. His mother had made him out of an old coat lining. He took immense delight in his own handiwork, which at first, astonished him with its high quality. He would work at a drawing or a scrapbook or a piece of woodwork quite independently, whistling softly through his teeth with satisfaction. Every few seconds he would rush up to see me, thrust his effort an inch from my nose, crying. “How about that, Miss Faye? How about that now?”

His skill grew with his confidence. And, soon, everyone was treating his work with respect, which did a great deal for him. He had always been the baby of the family. His mother petted him, abominably, and the children were frightened of his temper and gave in easily. As he grew busier, he had less time to work himself up into a real good fury; less need to do so to gain people’s attention. He had a new way of letting off energy and a new source of excitement. Sometimes, at the sight of a new toy, a lighted birthday cake, or, more often, his own work, he would stand and scream with delight. This was common among all six little boys in that gang: a new poster on the wall would set them whooping like mad. Of all the children at Little Laurel, I should most like to see R. B. at Pine Mountain. At the moment, he is “ripe for development.” He ought to make a fine craftsman: He is more skillful and confident than any of the rest of his family.

B. is a most hopeful carpenter. He was always up against the other children because he would retire for the afternoon into a corner with one of the two hammers and resent all interference. His whole life centered on that hammer. Each day as I walked down to school, I would hear a shrill voice from the depths of the S.’s cabin. “Get some bigger nails today, Miss Faye!” He always treated me as an old friend and equal, and would shout across the room for me to come quick and hold a tack, or fetch him the glue. He used up materials like lightning and the cupboards were full of B.’s strange, five-legged tables and bookcases into which no book would fit.

H and his nephew E were a good working combination — the best partnership in the school. H at first shy and lost, blossomed out as a most capable and understanding boss, taking full responsibility of E. P. ….

p.3

… whose bad stutter and slowness demanded a great deal of individual attention. Both boys had more imagination than the others and produced some good pictures and clay models. They were dreamy and less practical and active than the others. They would lie for hours, side by side on their stomachs across a bridge, watching the creek flow. I think H.’s easy tolerance of the others was unusual. He and E. P. were both six years old.

J. was a bright, attractive little boy, but he never really had a chance, as he was rather weak-willed and always under the domination of T. B. The partnership was an unequal and unfair one. J. did all the hard work, fetching and carrying, while T. sat back and waited for pleasant jobs like painting and varnishing. There seems to be a great deal of this dictatorship among the elder children of the community. It is easy to stamp out among smaller children. (At one time, T.’s growing power put her in danger of becoming too useful.) But, any kind of interference with the T-J combination was instantly spotted, and made trouble all around.

T, (11) set out to be boss of the school, and was responsible for any trouble there. He couldn’t get hold of the idea that he could do the things he wanted to, and that the teacher was not an enemy. He was obviously suffering from being kept down to a desk with a lesson book. As a result, he hated reading and writing. He seemed to have reached a stage when there was absolutely nothing to do, no source of excitement, amusement or stimulation, except in getting into trouble. At first, he did a great deal of loafing until he became interested in woodwork. He turned out a great deal [number] of doll’s furniture, — had some good ideas, and made a few toys at home, which pleased his mother. He wasn’t nearly such a good workman as his brother. R. B., being slap-dash, and impatient of directions, and uncritical of results. But gradually, towards the end, when his work fell to pieces or stood crooked, for himself, he saw that slower and more careful work was needed. I think he should be given a chance at Pine Mountain! His father won’t help or encourage him at all to follow his bent for woodwork. There is good stuff in all the B’s, and T. needs simply a special kind of discipline.

Corresponding to the gang of smaller boys was a group of four little girls Three of them needing a great deal of personal attention and encouragement. S. M. (7) was full of ambition, but always in some dreadful tangle from which she had to be extricated that very second. She was very affectionate and grateful and needed a great deal of kindness, under which she developed a lot more self-confidence and perseverance, and ended up as quite a force. When we were playing Daniel Boone, she, alone, with our B., stood out from the others who all wanted to be savages, and offered to be wife to R. B.’s. D. S. suffers from being shouted at by her…

p.4

… Mother, and from the extreme reliability and successfulness of her sister, W. … both M.’s are terrific workers. They work unquestioningly and thoroughly. W. was a skillful, neat little girl who did everything beautifully, but without much originality or imagination. Both children suffer from the dictatorship of their mother and are paralyzed when she is around. I think they would do well at Pine Mountain. Because they respond very much to good treatment and ideas of better ways to do things. When school was out, when afraid, she went home and fixed up her own and S.’s bedroom as a perfectly beautiful playroom, with flowers, toys, and pictures arranged in faithful imitation of the schoolhouse. The room was an example to the rest of the home.

L. B. (8) and A. C. (10) Dissipated most of their energies in getting mad. They liked to make a scene. However, they got plenty of chances to satisfy their tastes for showmanship and dramatics in dancing, playing house, and acting as Indians and Pioneers. L. was a messy and impatient worker, but very quick and mentally alert. She grumbled a lot, and fanned flames of discontent in others. I think this is entirely her mother’s influence. L. is much too old for her age and copies her mother in everything. It would be a great thing for her to come to Pine Mountain, away from her background of discontent. A. C. had had good training at home, and was ahead of everyone in cleanliness, sewing, painting, etc., which unfortunately, she had been told often enough by her mother. I don’t think she needs Pine Mountain nearly as much as the rest of Little Laurel. Her mother is quite an enlightened person, materially, and the home is an example to the rest of the community. I think all the C.’s suffer from a smug superiority, but this is inevitable. Their home is the best for miles around.

B. M. B. (13), a clever child, is much more responsible than her mother, — more straightforward. I hope she will get to Pine Mountain as she herself hopes. She read as many books as I could provide her with, and absorbed and remembered every detail in them. I hope the promise, she shows is not ephemeral. She took a lot of schoolwork home to finish, and was very good at keeping her promises. She and R. B. seem to be the hopes of the family … If they get away from it soon enough (to return later, of course).

A. T. (12) Is the only child besides … [?] who can definitely get along well without Pine Mountain. Her home background is even more meager than the B.’s, but more stable and contented.. I think her mother, Mrs. B. S. is quite a fine person. A. T. is one of those good-natured, homely people who put everyone at ease. She used to entertain our visitors with the story of how her Pappy was shot in mistake for her grandpappy. She was always kind, patient and cheerful, and never grumbled. Like her mother, she seems to flourish under a hard life.

p. 5

During the winter, our activities were mostly drawing, sewing, woodwork, story-reading, and dancing. We also wrote letters and party invitations. The children seemed to suffer from being taught reading and writing in a perfectly meaningless way, and there is a general feeling that words and letters are no kin to them. They got over the old tradition of drawing with stencils, and soon spoke of them with scorn. But, I came to the conclusion that drawing is an unnatural thing; even the big ones find it tiresome. On the other hand, they love to make things out of clay or wood and decorate them with paint for their homes. (This seemed true of Group B at Pine Mountain, too.) There seemed little use in emphasizing drawing. There was a most prolonged interest in sewing, which the mothers seemed to be too impatient and too busy to teach the children. The girls made aprons for cooking, also dolls dresses, and bedclothes. Dolls were borrowed for the night and arrived back the next day in new outfits. The boys furnished the Playhouse with chairs, tables, dressers, and cradles, and made barns for horses and mules, also a Noah’s Ark, for which everyone designed 1 animal.

Mr. Callahan [Boone Callahan] gave us the ends of paint cans, and everything was very gay and piebald. Everyone helped to make and decorate the paper walls and roof of the Playhouse. This called for a lot of accurate measuring. A yardstick reminded the older ones of arithmetic, and they never really enjoyed it, but our B. and T. developed a perfect mania for measuring every object in and out of reach. Our B. learned quite a lot about numbers and T. would count the drawers in the doll’s bureau, and could bring you three bricks when asked. Our B. and Bby. wanted to learn to write, and took great delight in making rows of letters until at last they got a perfect one.

The Victrola aroused great enthusiasm. T. learned to work it properly, with J. as an understudy. Favorite records, such as songs of our native birds and Come All Ye Faithful were played. 6 or 7 times a day. One day, we discovered that one of the mysterious side tables in the room was really a “dulsitone” piano. S. learned to play about three-fourths of Three Blind Mice, which gave her endless pleasure, and B. M. and A. would sit for hours playing doubtful chords and singing very loudly such favorites as What Would You Give in Exchange for Your Soul. The country dance records brought about a passion for dancing among the girls. They began by improving a kind of running set. Then I taught them two easy figures which they would perform alternately with great excitement. We tried to learn two country dances but had to put in our own variations. How we astonished the mothers when we danced for them at our Mother’s Day Party. One day in the Spring Mr. Seaman came down and taught us a lot of new games and dances. We were growing rather tired of Farmer in the Dell in green gravel. The children picked the new ones up very quickly and remembered every detail about them long after I had forgotten. T. liked Mr. Seaman and was at his best that afternoon. One of his troubles is that he doesn’t care about women or girls at the moment.

p. 6

As soon as the weather was warm enough, we moved down to the creek. It was a perfect place: a flat stretch of grass, sand, water, rocks, and plenty of scattered rails for house building. E[?], we built many log cabins and Indian dens, and the children played Daniel Boone, with bows and arrows, red paint, and ax, and a broom as equipment. The fights were a little unequal, as all but two were Indians. There was terrific enthusiasm for cooking, which lasted the whole of the summer. We were never short of supplies, for the Begley’s kept us in cornmeal, flour, milk, coffee, and baking powder, and on one memorable day, Swanee brought a great piece of fat pork. We made biscuits, cornbread, cocoa, coffee, “health” tea (from herbs). In stakes, Miss Snyder, riding home, “was entreated to come and share our bar [bear] meat.” We cooked under ultra-hygienic conditions: knives and plates were washed over and over again, and the meat was held under the spring both before and after cooking, and was flavorless but pure. There was a fashion for cleanliness. which originated in two large bars of soap I had brought for scrubbing the floor, but which were adopted voluntarily and with zeal for toilet purposes. Twice, the soap was stolen but mysteriously reappeared.

We did a lot of modeling [clay] by the creek. The mothers all liked our clay dishes very much and one of them took to pottery herself and came to Pine Mountain to get the right kind of clay from our bank.

Our Easter Party was quite successful. Thirty people came, including all the lost sheep from the other end of Little Laurel. We had a birthday cake for B. M. the last day of school. May the 11th, we had another party, on a grander scale, to celebrate all the birthdays in May; Mother’s Day; and the end of school. There were four identical white birthday cakes belonging to T., L., S., and myself. The mothers were all given presents we had made. Turner had made his mother a full-sized cradle for her big doll … and faithful J. had made a cradle too, for his mammy. Mrs. Metcalf was showered with gifts made by her industrious children and was so pleased that she joined in all the dances. We danced our feet off, and then the cakes were served out of chestnut leaves. The party ended with our drawing lots for all the toys, etc., we had made, and for every bit of school equipment, including the popular soap. The last I saw of the Vacation School was the familiar playhouse moving mysteriously up the hill in the direction of the B.’s, apparently on its own. W., staggering home with the big doll’s house in her arms, and R. B. sitting by the wayside, his face shining like a little angel, licking sugar from the birthday cake knife.

I think the Vacation School certainly ought to be carried on. The children have a right to be [have] more than 7 months of schooling a year, and the old legend about there being enough work at home to employ every child over five seems untrue. I wish it were possible for the state to authorize the Vacation School and pay the teacher a salary. The only trouble with the school this year was that it was conducted on a free charity basis, and not …

p. 7

… a solid working one. I think the people would feel very much more in sympathy with and responsibility to the Vacation School if they knew the teacher was being paid by the state, and was not there on casual, voluntary, and inevitably patronizing terms. Far from harming the relationship between the teacher and the trustee and other parents, it would give it more dignity and stability. I don’t think the people really like being almost forced to take something for nothing. I don’t know how willing the state would be to provide for an extra three months of schooling. It sounds unlikely.

Judith Fay

GALLERY: ALICE COBB 1937 Transcribes JUDITH FAY’S “Vacation School at Little Laurel’

- 001 fay_judith_vacation_sch_001.jpg

- 002 fay_judith_vacation_sch_002

- 003 fay_judith_vacation_sch_003

- 004 fay_judith_vacation_sch_004

- 005 fay_judith_vacation_sch_005

- 006 fay_judith_vacation_sch_006

- 007 fay_judith_vacation_sch_007

- 008 fay_judith_vacation_sch_008

- 009 fay_judith_vacation_sch_009

- 10 fay_judith_vacation_sch_010

- 11 fay_judith_vacation_sch_011

- 011 fay_judith_vacation_sch_011

- 12 fay_judith_vacation_sch_012

- 013 fay_judith_vacation_sch_013

See Also:

ALICE COBB STORIES A Trip to Turkey Fork and Big Laurel 1937