Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 22: Environmental Education

Warblers

ENVIRONMENTAL EDUCATION Warblers

TAGS: warblers, Sutton’s Warbler, Kentucky Warbler, birds,ornithology, Pine Mountain Settlement School birds, Harlan County, KY, rare birds; songbirds, Yucatan, Mexico,

How do you know but ev’ry bird

that cuts the airy way,

Is an immense world of delight,

clos’d by your senses five?

William Blake

SUTTON’S WARBLER

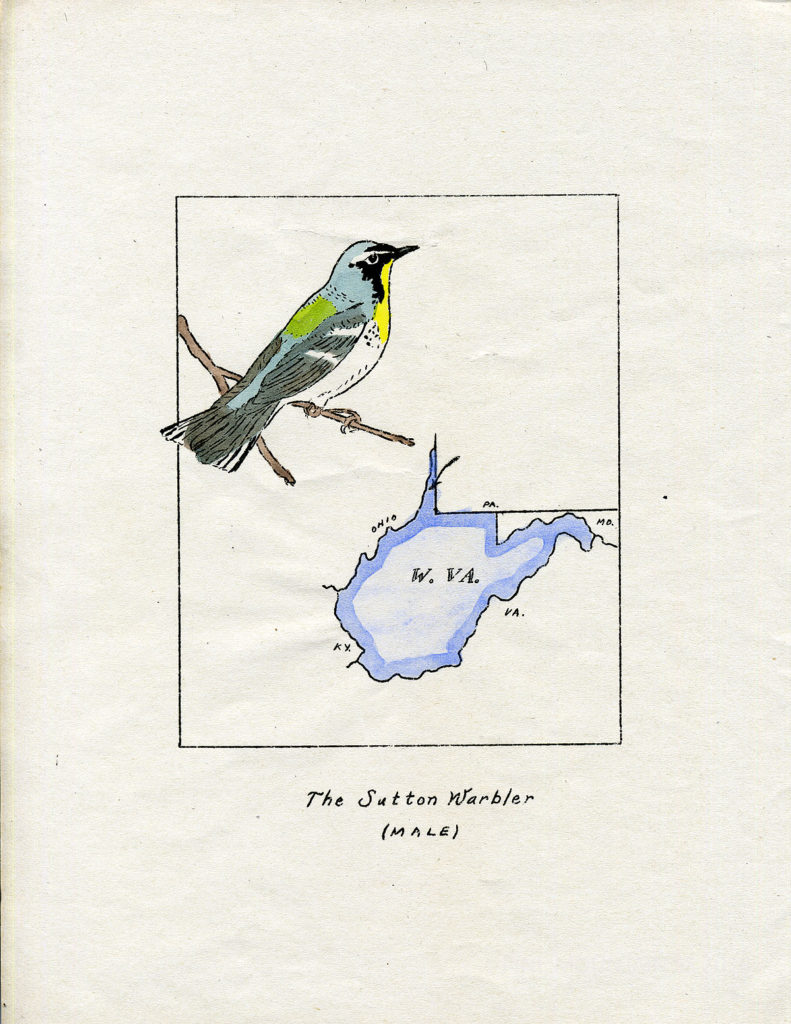

Sutton’s Warbler as depicted in the article by Thomas R. Henry in the Snowy Egret, 1942,Vol 16 No. 1.

In the Spring 1942 issue of a little-known publication called Snowy Egret Vol 16 No. 1, Thomas R. Henry, of the Springfield (Mass.) Republican, wrote a short article about the discovery of a new warbler, the Sutton’s Warbler. The rare bird was spoted for the first time in 1939 in West Virginia and was for the first time described in the publication NANA, a bird-watchers guide.

The small bird at first was not defined as a new species but was thought perhaps to be a hybrid variety of the common yellow-throated and parula warblers. Hybrids, rarely reproduce but can do so in optimum environments.The discovery of the new warbler species, that found in West Virginia, was quickly confirmed by ornithologists at the Smithsonian and published in their journal.

The Pine Mountain Valley is an optimum environment for warblers as they are ground feeders and prefer deep, lush forest floors similar to those that surround the Pine Mountain Settlement School and apparently in the West Virginia mountians. The Sutton Warbler follows the same feeding, nesting and diet patterns as its more common species, the Kentucky Warbler. This may, in part, explain why it took so long to discover that it was a separate species.

Adding credence to the habitat preference of the Sutton Warbler, is that of the so-called “Kentucky Warbler” [Oporornis Formosus (Wilson)],one of the most common of the eastern warblers. Their frequent sighting in and around Pine Mountain School and their song, similar to that of a wren, may often be heard in the deep and moist woods of the north slope of the Pine Mountain.

When Henry wrote about the new discovery of the warbler in West Virginia in 1942, it made an immediate impact on the bird watchers of America. The discovery of the small warbler in the southern panhandle of West Virginia, an area that was well covered by bird watchers seemed remarkable. The discovery of this new and apparently secretive little bird was, at the time of Henry’s article, the first new species discovered in 21 years. The last discovery of a new bird species had been in Florida. Remarkably, the little bird appeared to be hiding in plain sight.

The Smithsonian’s curator of birds noted the strange circumstances of the bird’s discovery and suggested, as had other ornithologists, that the bird had not been identified as a new species earlier because of its resemblance to the other common warblers in the area, such as the Kentucky Warbler. Further, the ornithologists suggested that the new species had most likely not been around for very long.

Henry recounts the details of the West Virginia discovery. He describes how Karl W. Haller, an ornithologist from Bethany College of West Virginia came upon the warbler

“… while crossing a section of scrub pine growth, [he] was attracted by a peculiar song, a rapid, buzzing trill ascending the scale and dropping off at the end, which was repeated quickly, twice in succession. It was quite similar to the song of the parula warbler, well known in the area.

When he located the bird, however, it was quite different in appearance, being similar in coloring to the yellow-throated warbler, a southern bird never found in that spot, so far as is known. When collected it also was found to have some characters of the parula warbler. It was a small bird with a yellowish olive patch on the back, a trace of brown on the sides and flanks, a tinge of raw sienna across the throat, and a little white on the tail.

This bird was a male and, by itself, signified very little. It might be a hybrid between the parula and the yellow-throated warbler, altho the latter had never been reported in the region. The real significance of the find came when another bird was shot [!] in a sycamore-willow swamp about 18 miles away. This was a female, almost identical in every respect to the male. She soon would have laid eggs. This is the acid test of a “species” — the ability to perpetuate itself.”

The more common Kentucky Warbler was discovered by Alexander Wilson in 1832 and he named it for the State where he found the species to be most abundant. Dr. Henry Smith Williams in his The Private Lives of Birds, (1939) wrote

“The creation of new species under our eyes is one of the most interesting phenomena of birdlife; and its observation naturally stimulates speculation as to the probability that similar unions of allied species have taken place, and are still taking place, in particular at the borders of breeding ranges, or wherever two allied species are so unprosperous as to become rare enough to make the findings of proper mates uncertain.”

The Audubon Field Guide describes the Kentucky Warbler and cautions on the impact of global warming and removal of forest habitat by logging which will severly impact many bird species now common in the Central and Southern Appalachians. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/kentucky-warbler

Thomas R. Henry in his defining article, then points out that

Altho the editors have no breeding records of the yellow-throated warbler from eastern Kentucky, they do have three spring records for the sycamore warbler, a closely related subspecies. They are: April 18, 1936 (Pippapass, KY); May 10, 1936 (Hueysville, Ky); and May 6, 1939 (Prestonsburg, KY). The parula warbler is found breeding quite regularly in that section. Strangely enough, neither of these species has been observed in the Berea, KY region.

KENTUCKY WARBLER

The habits of the new warbler species is not described fully in Henry’s article but appears to follow the habits of most warblers such as the Kentucky Warbler in the central Appalachians. According to Prof. Maurice Brooks (1940), they seem to be

“at home in a number of forest types, southern mixed hardwoods, scrub and pitch pine mixtures, oak-hickory, and northern hardwoods. …. As with many other sylvan birds, ravines seem especially to attract them.”

“… this warbler is a common victim of the cowbird. … Snakes and prowling predators have been known to rob the nest of this other ground-nesting species.

Alexander Wilson relates that the Kentucky Warbler winters in southern Mexico and as far south as Colombia, South America. Dr. Skutch, another bird lover, notes that, ” Of all the wood warblers, resident or migratory, the Kentucky warbler is the species most often seen in the undergrowth of the heavy lowland forests of Central America. ” M.A. Frazar, an early bird watcher writing in 1881, recorded “‘large numbers’ of Kentucky warblers migrating across the Gulf of Mexico, when his ship was about 30 miles southof the mouth of the MIssissippi River; they had apparently coe from Yucatan and were flying due north.” In the Spring, generally in April, the birds migrate back to the Appalachians. If global warming continues, that journey will be much longer as seen in the Audubon Field Guide map of the bird’s habitat.

GALLERY

- Warbler article warbler_002

- Warbler article warbler_003

- Warbler article warbler_004

- Warbler article warbler_005

- Warbler drawing

Bibliography:

Henry, Thomas R. Snowy Egret Spring 1942, Vol 16 No. 1, [PMSS Collections]

Audubon Guide to North American Birds. https://www.audubon.org/field-guide/bird/kentucky-warbler

The Cornell Lab. All About Birds. Kentucky Warbler Overview https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Kentucky_Warbler/overview

Bent, Arthur Cleveland. Life Histories of North American Wood Warblers, Smithsonian Institution, United States National Museum Bulletin 203, 1953. pp. 508-512. Accessed 2019-11-10

hhw