Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 17: PUBLICATIONS PMSS

Notes – 1936

November

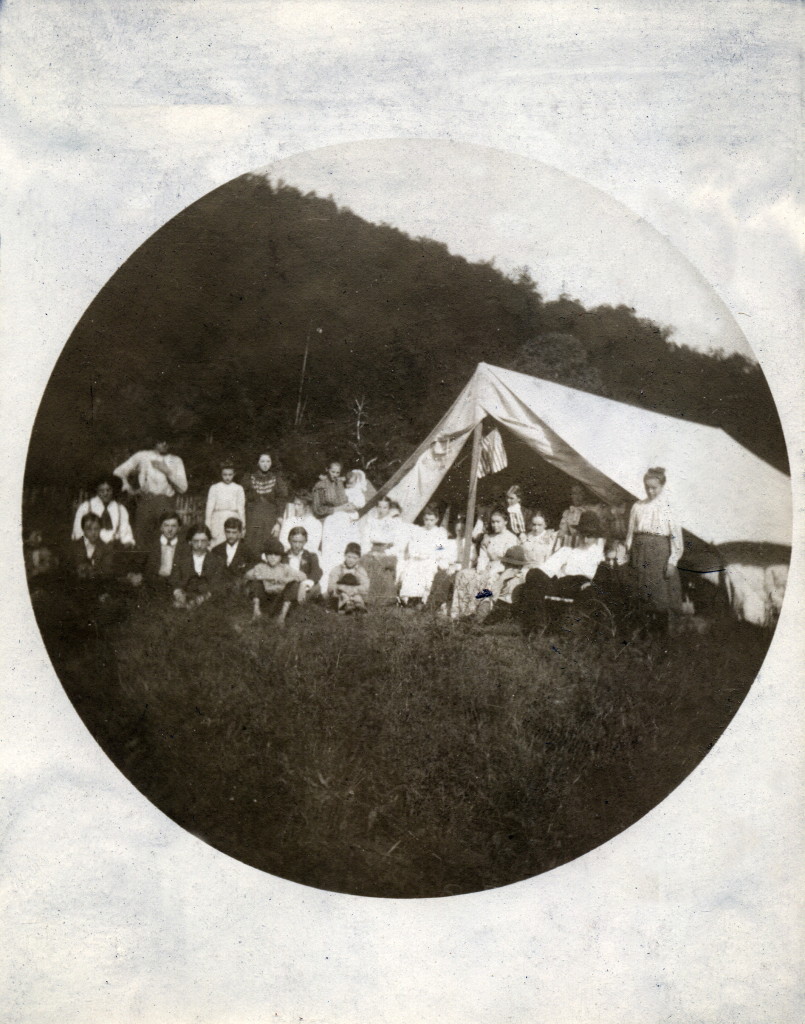

Summer camp at Sassafras, KY, 1901. Katherine Pettit Sassafras Album. [sas_002.jpg]

NOTES – 1936

“Notes from the Pine Mountain Settlement School”

November

GALLERY: NOTES – 1936 November

In every way [Katherine Pettit] tried to keep [the mountain people] off the dole, which she hated with all her might. – Lucy Furman

- NOTES – 1936 November, page 1. [PMSS_notes_1936_nov_001.jpg]

- NOTES – 1936 November, page 2.[PMSS_notes_1936_nov_002.jpg]

- NOTES – 1936 November, page 3.[PMSS_notes_1936_nov_003.jpg]

- NOTES – 1936 November, page 4.[PMSS_notes_1936_nov_004.jpg]

TAGS: NOTES – 1936 NOVEMBER: Katherine Pettit, Cumberland Plateau, Wilderness Trail, Perry County, Berea College, Kentucky Federation of Women’s Clubs, Hazard, first rural social settlement, Hindman, Troublesome Creek, Harlan, fundraising, Lucy Furman, May Stone, Uncle Solomon Everidge, Ethel DeLong, Big Laurel, Line Fork, mountain culture, Kentucky Sullivan Medal

TRANSCRIPTION: NOTES – 1936 November

P. 1

NOTES FROM THE

PINE MOUNTAIN

SETTLEMENT SCHOOL

PINE MOUNTAIN * HARLAN COUNTY * KENTUCKY

Copyright, 1936, by Pine Mountain Settlement School

Volume VIII NOVEMBER, 1936 Number 1

Katherine Pettit

Pioneer Mountain Worker

By Lucy Furman, author of The Quare

Women, The Glass Window, Lonesome Road, etc.

KATHERINE PETTIT originator of the rural social settlement and of the settlement school, and worker for forty years in our mountain section, was born on a Bluegrass farm near Lexington, Kentucky, of pioneer stock, both sides. One forebear had brought the first printing-press across the Appalachians, and published the first newspaper in the new country.

From childhood Katherine Pettit had heard with interest of that isolated section to the South and East of the Bluegrass, from which little news came out save of bloody feuds and perpetual moonshining. The Cumberland Plateau, comprising more than a fourth of the state’s area, is a maze of sharp valleys and steep slopes, with practically no level land, and no navigable streams. The men who left the main drift of settlers traveling the Wilderness Trail 150 years ago, to enter this maze, seldom if ever came out, and after five generations their descendants were still living the pioneer life.

Reading in the newspapers of March, 1895, that the terrible French-Eversole Feud in Perry County was ended by the death of the last fighting man, Katherine Pettit went up to Perry’s county-seat, traveling one day by the newly-built railroad to Jackson, in “Bloody Breathitt”, and two more days by wagon to Hazard, which at that time was a village of 500 people, with cows and geese wandering through its principal street, and hogs wallowing in the deep mudholes. For some weeks she remained, hearing in the homes tales, tragic as those of ancient Troy, of the “war” just ended, and getting acquainted with the women, many of them widowed by the feud, and with large families of children. She longed to remain and teach them better ways of homemaking; but because of duties in her own home, this was not possible. For three years she could do nothing more than make visits every summer, bringing with her, besides the package of flower-seed handed out to every woman she met, traveling libraries of the State W. C. T. U. and the State Federation of Women’s Clubs.

In the spring of 1899, she made a month’s walking trip, with a woman missionary, through the wildly beautiful Pine Mountain region, in Harlan County. Up every creek and branch they tramped, visiting every home, stopping overnight wherever dark overtook them. And everywhere they found the same conditions, families producing in their steep fields and narrow strips of bottom, everything necessary for food and clothing, self- sufficient, independent, self-respecting. But other things were not so good, – the drudgery of the women, who not only cooked, washed, made garden, helped hoe the corn, spun, wove and made garments and “kivers” for their families, but often, also, brought forth a child every year; and the shocking lack of opportunity for the young, boys being sometimes sent to the few, short-term district schools, before being turned loose to drink and…

p. 2

…shoot at will, but education being considered superfluous for girls, who, marrying often at thirteen and fourteen, began at that tender age the treadmill of their mothers. While it was delightful to hear in the homes the language of Shakespeare, and the fine old English and Scottish ballads, it was sad indeed to see people of good stock deprived of the advantages of their age.

One day when Miss Pettit sat alone on top of the great ridge of Pine Mountain, very footsore, stout shoes in ribbons, the missionary having gone down the side to drive up a cow whose milk should refresh them, two men came up the trail, saying they had walked a long way, from the mouth of Big Laurel, to beg her to start a school on land they would give her. She told them she could not come then, but that if it was ever possible, she would.

Two weeks later, the Kentucky Federation of Women’s Clubs was meeting at Frankfort, the capital, when a quaint letter was read from a Hazard preacher, thanking the club women for the traveling libraries, and asking them to send up for the summer “a woman, a gentle, womanly woman, a dear old-fashioned woman to hold classes in home-making.” Along with these, he said, the “moral features” could be made interesting.

Miss Pettit, just entering, was made to tell of her trips. Before she could finish, one woman after another sprang up, saying, “We must do something!” At that time the new social settlements in London, Chicago and New York were much in the public eye. Miss Pettit said she thought that a Christian Social Settlement was the thing needed at Hazard. Asked if she would take charge of one for the summer, she said yes. Money was instantly subscribed for expenses. As she left the platform, a young woman sitting there, at that time Secretary of the Federation, said to her, “If you need me, I’ll be glad to help”. It was May Stone, of Louisville, like Katherine for five generations a Kentuckian, an ancestor having been among the first seventy men to come out the Wilderness Trail in 1775.

Shortly afterward, on a wooded spot in Hazard, in a tent borrowed from the State Militia, and gayly decorated with flags, pictures, red cheesecloth, and bright kindergarten chairs, the first rural social settlement ever undertaken was begun by Katherine Pettit, May Stone, and three other young women, with classes in cooking, sewing, home-nursing, singing, and kindergarten, daily Bible and temperance readings, and all kinds of “socials” and play-parties.

From all the creeks around people came to see “the quare, fotched-on women from the level land”, and enjoy the good times. A visitor of the late summer was a beautiful old man with a shock of white hair, wearing a crimson linsey hunting-shirt and linen trousers, who, after sitting silent all day, watching, said, “Women, my name is Solomon Everidge. Some calls me the grand-daddy of Troublesome. Sence I was a leetle shirt-tail boy, hoeing corn on the mountainsides, I have looked up Troublesome, and down Troublesome, for somebody to come in and larn us something. My childhood passed, then my manhood, now I am old, and still nobody hain’t come. I growed up ignorant and mean; my offsprings was wuss; my grands is wusser; and what my greats will be if something hain’t done to tame and civilize ’em, God only knows! When I heared the tale of you women, I walked the twenty-four mile acrost the ridges to sarch out its truth. I am persuaded you air the ones I have looked for all my lifetime. Come over on Troublesome, women, and do for us what you air doing here.”

The next summer, that of 1900, still under the Federation, Miss Pettit and Miss Stone, with four helpers, went to the much smaller village of Hindman, at the Forks of Troublesome Creek, in Knott County, setting up their five tents on a steep hill-shoulder 250 feet above the court-house. From far and near came young and old, to see the “cloth houses” and attend the classes and socials. The brightness and “pretties” were specially enjoyed by the older women, in their black sunbonnets and somber frocks. They gave names to the fair “furriners”. Katheryne was the “up-and-comingest”, May the “ladyest”, others were the “goodest-cooking”, or “handiest with least ones”. In the sewing classes, more…

p. 3

…than a hundred were enrolled, thirty-six being young men and boys, the same who, for a short time after the women’s arrival, and for years before, had made the nights hideous with drinking, riding up and down the one street, yelling, shooting up the town. It was an amazement to the people to see these “mean” boys sitting on the hill hemming handkerchiefs, and not only that, constituting themselves a special guard to keep order and quiet in the village, nights.

No wonder that, after the summer’s work was ended, Uncle Solomon and the citizens held a mass meeting, begging the fotched-on women to stay always, not only to continue the social work, but to found a school, for which land and logs were offered.

The only kind of school Katherine and May believed in was an industrial one, where hands and minds could be simultaneously trained, and where the young could pay for their board with their labor. This would mean much land for farming, gardening, dairying, etc., many buildings for social work, residences, shops, hospital, and the like, – – a large outlay of money. Though both possessed comfortable means, what was this in the face of such a need? And both abhorred the idea of going out to make talks and raise funds. When the decision had to be made, they sat one night on a high hill-shoulder, in the moonlight, considering, deeply, prayerfully. Katherine had three life-mottoes, “If a thing ought to be done, it can be”, “God never fails”, “Learn by Doing”. May, too, was ready to venture far. At midnight, from that high hill-shoulder, the two stepped out upon faith alone.

Starting out to make talks, chiefly to women’s clubs, they did it in a way incredible to modern publicity-hounds. Newspaper people were always excluded from the room. Not one word about themselves or their work was permitted to get into print. They refused to exploit and publicize the highlanders, whom they regarded as kinsmen unjustly de- prived of their rights.

This of course made money-raising much slower than if done with a blare of publicity; and it was the summer of 1902 before they were able to open, in even a small way, on the few donated acres, the first settlement-school ever thought of. This is no place to tell of the Hindman Settlement School, which, in ten years’ time, had become so notable for its work along social, health, medical, educational and industrial lines, as to call forth from the Professor of Sociology of a great Northern University, the following words; “To my amazement, I have found the ideal Twentieth-Century school in the remote heart of the Kentucky mountains.” A few of the difficulties surmounted may be mentioned: the hundreds of logs donated were living trees on the ridgesides, which must be measured, marked, cut, hewn square by hand, snaked down the slopes by ox-team, and then floated or hauled to the school grounds. Stone for foundations and chimneys must be quarried from the cliffs. Shingles for the roofs must be hand-riven, with fro and mallet. Window- frames and glass, nails, lime for the mortar-chinking, had to be hauled a three-days journey from the railroad, across five ridges, along a dozen rocky creek and branch-beds. Furniture for all the buildings must be made in the shops. And all these operations had to be supervised by the women themselves, chiefly Miss Pettit, who also started all the farming activities.

During the years, she never forgot the men of Harlan, nor did they forget her. Though she was having offers of land and timber from many mountain counties, when that of Uncle William Creech, of 135 fine acres where four creeks head up against Pine Mountain, came to her, in 1913, she left the Hindman work in the hands of May Stone, and came gladly to the new field, bringing with her as helper a gifted young New Jersey woman, Ethel deLong, who for two years had been principal of the school department at Hindman.

Of the building-up of this work, readers of the Pine Mountain News Notes already know well. The same lines of social and health work as at Hindman were followed here, and the smaller Settlements at Big Laurel and Line Fork; but this not being a public school, its curriculum could be better adapted to local needs. And special stress is placed upon the preservation of the old ballads and folk songs and folk dances, the cottages being…

p. 4

…gay in the evenings with the notes of dulcimer and banjo and fiddle, and the calling of figures.

At both Hindman and Pine Mountain, Miss Pettit not only kept in daily contact with all the industries, but was in close personal touch with the boys and girls. And how they did like her! One wrote her, later, “You always did hit straight from the shoulder, Miss Pettit”: Frank, free-spoken as the highlanders themselves, she never hesitated to “fault” the ways of young or old, and tell them of better ones. And they took it as it was meant, — understood her better, probably, than did the level-landers.

What she has meant in the lives of the young, is shown by their letters. One boy, after twenty-eight years, writes, “The spirit of your work is still an inspiration to me”. A girl writes, “I could never forget you, there is no one in the world I love better than you”. Two others send this message on a Mother’s Day card from Berea College, “Harriet and I are sending this as a note of appreciation for all the lovely things you have done for us. You have been a mother to dozens of mountain children who are just as grateful as we for the wonderful opportunity you have made possible”. Another girl writes of a young man in her family. “John hasn’t drunk any for a long time. He says, ‘You know it’s funny, but whenever I start to do something that’s not right, it seems as if Miss Pettit is going to step right up and see me’.” And still another girl, now married, says, “I’ve been thinking of you this month because the bluebells are in bloom. They are here for you. You told me once, ‘If ever I come to see you, I want to find your yard filled with flowers’.” And a boy writes, after he had left Pine Mountain, “It has been a long time since I’ve seen you, but not so long after all, only three years. Nothing seems the same since you left. I even think the world has changed since you left.”

In 1930 Miss Pettit gave up the headship of Pine Mountain work. But not for a life of ease and comfort. Free at last after thirty years, from the terrific burden of raising money for, and running, large institutions, she entered upon a new pioneer labor, what she called free-lance-work in the mountains. The need of this was terrible. The hundreds of coal mines opened during the World War had been closed, almost all, by the slump of 1929, and men who had sold their land for a song to work in these had now neither land nor work. She went from neighborhood to neighborhood, getting families back on pieces of land, teaching them by intensive farming to produce food for themselves, bringing them also some paying work, — orders from gift-shops for hand-made wooden utensils, trays, trenchers, keelers, piggins, noggins, and also for hand-woven fabrics. Their children she got into some of the now numerous schools; their sick she sent down to hospitals. In every way she tried to keep them off the dole, which she hated with all her might. Always she was giving out health, agricultural, temperance and forestry bulletins.

She had worked longer than any living person in the Appalachians, knew mountain people and problems as no other person did. To various government and state agencies she was a valued unofficial adviser. And with it all, she was modest as in the beginning. Publicity was always anathema to her. Newspaper reporters sought interviews in vain. Her best friend would never have heard, from her, that she had received the Sullivan Medal for distinguished service to her state.

And now she is gone, — after months of cruel suffering, has died as gallantly as she lived. Shortly before going, she wrote to an old friend and fellow-worker, “This has been a glorious world to work in. I am eager to see what the next will be.”

Set Up and Printed by Students of

PINE MOUNTAIN SETTLEMENT SCHOOL

Previous:

NOTES – 1935

Next:

NOTES – 1937

See Also:

KATHERINE PETTIT Director Biography

ETHEL De Long ZANDE Director Biography

Return To:

NOTES Index