Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 18: PUBLICATIONS RELATED

Series 27: SCRAPBOOKS

Scrapbook Before 1929

R.L. Hartt, “The Mountaineers Our Own Lost Tribes”

1918

“The Mountaineers: Our Own Lost Tribes” by R.L. Hartt. illus. 2. Illustrated by John Wolcott Adams. [mou_00`11]

TAGS: Scrapbook before 1929, Rollin Lynde Hartt, John Wolcott Adams, The Century Magazine, The Mountaineers Our Own Lost Tribes, Shakespearean English, Central Appalachian mountaineers

SCRAPBOOK BEFORE 1929:

R.L. Hartt, “The Mountaineers: Our Own Lost Tribes” 1918

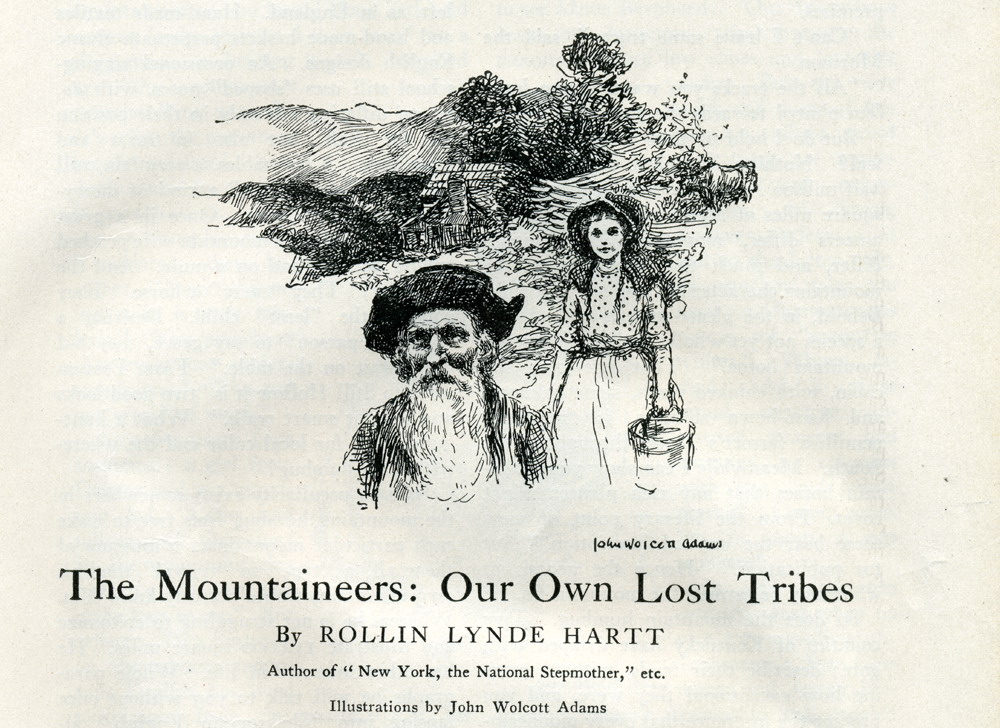

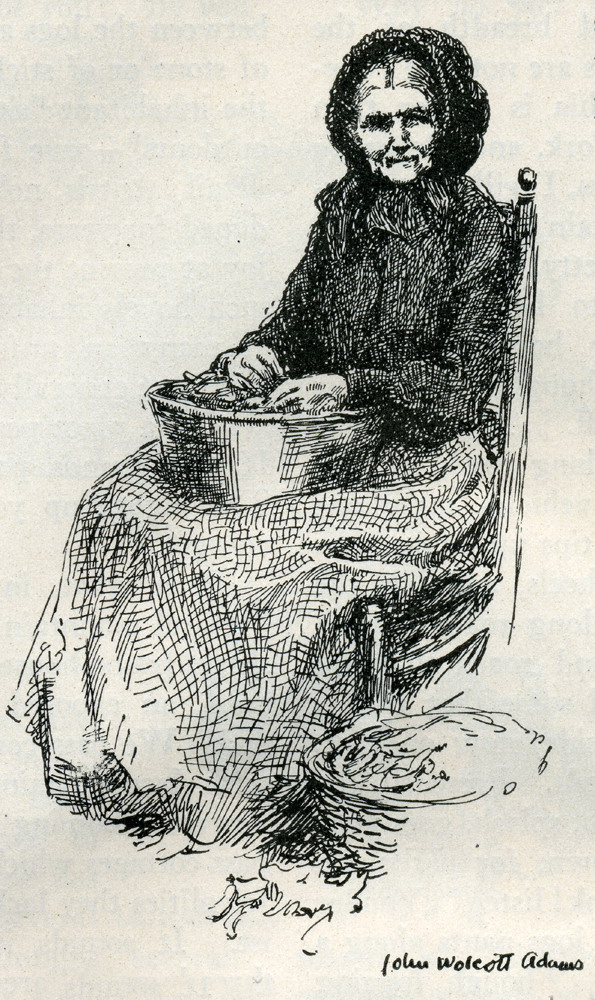

This article, “The Mountaineers: Our Own Lost Tribes,” describes the variety of life in the Central Appalachians during the first quarter of the twentieth century. Written by Rollin Lynde Hartt and illustrated by John Wolcott Adams, it was published as a vignette in the January 1918 issue of The Century Magazine, (New York City: volume 95, no. 3, pages 395 – 403), and also printed by The Century Company in 1918 as a book with the same title.

Rollin Lynde Hartt was an early 20th-century journalist and author of several books. Ordained as a Congregational minister he was educated at Williams College. He reported for several journals popular in his day and was outspoken in his views of popular culture. His reporting and views on the Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy were known nationally and mentioned in Time Magazine. Wikipedia

John Wolcott Adams, (1874-1925) the illustrator of the article, studied at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. In 1898 he went to New York where he attended the Art Students League of New York classes. He was interested in the theater and designed sets for theater productions. His drawings appeared in many well-known magazines such as Colliers and The Saturday Evening Post.

TRANSCRIPTION

The Mountaineers: Our Own Lost Tribes

By ROLLIN LYNDE HARTT

Author of ” New York, the National Stepmother,” etc.

Illustrations by John Wolcott Adams

Page 395: mou_0001

A DELICATE, dreamy-blue haze over-hangs the Southern Appalachians. Azaleas, laurel, and rhododendrons clothe their slopes. Log cabins abound. The mocking-bird carols blithely. Cow-bells tinkle. Up from abysses of unimaginable beauty come now and then snatches of some three-hundred-year-old British ballad. But it is not of such charms as these that the lowlander speaks when he says, with endearing Southern vehemence, “Take my advice, Brother, and don’t go back North without seeing our mountains.” No, it is of the mountaineers that he speaks. It is of “those wonderful, wonderful people.”

Wonderful, indeed, they must be if all you have read of them is true at once. They flocked to the World’s Fair, they fought in Cuba; yet they have never seen a train. Not knowing their alphabets, they rave when a writer maligns them. Hopeless degenerates, they have produced Presidents, governors, generals, and jurists. They pick off “revenues” with unerring aim. This they owe to their diet of “moonshine” whisky. They exterminate one another so persistently that their numbers have risen to five and a half millions. They speak Shaksperian English. Example: “Oh, my brethering-ah, how well I remember-ah, jist lack it war yistidy-ah, the time I foun’ the Lord-ah!” You end by regretting the colorless, undescriptive name Appalachia. Call it instead Chestertonia!

Journalists, novelists, and authors of serious books conspire to give just that impression; sometimes the facts do. There were moonshiners who voted for prohibition. There was a feudist who apologized to his victim and, kneeling beside the dying man, prayed for his soul. There was a polygamist with a clear (because Biblical) conscience. When a Mormon

Page 396: mou_0002

elder arrived, he ordered him off his premises.

“Can’t I leave some tracts?” said the Mormon.

“All the tracks you want, if you leave ’em p’inted towards the gate.”

But do I hold up these instances as typical? Nothing is typical of five and a half million Americans inhabiting 112,000 square miles of alpine paradise. Mountaineers differ, mountain neighborhoods differ, and much that characterizes the mountains characterizes also the lowlands. Behold, in the please-contribute leaflet of a species not yet wholly extinct, “a typical mountain home.” That one-room log cabin, with chinked walls, stone chimney, and hand-hewn shingles, is the usual penniless farmer’s abode throughout the South. Meanwhile I can show you mountain homes that any rich planter might covet. From the literary point of view these bear the implied inscription, “Not for publication.” Hence the genesis of what may be termed the mountain fib.

So does the mountain humbug. Two counties of Kentucky have dripped with gore; describe their feuds, without owning how exceptional they were, and you prompt the inference that every mountaineer, all the way from northern Virginia to midmost Alabama, is “warred up ag’in’ his neighbors.” Here and there a family goes to bed in one room minus even a curtain for privacy. State it; stop there. Readers will think all mountaineers uncivilized. In certain remote “coves” “tooth-jumping” survives; a nail is held slantwise against the embattled molar, a hammer does the rest. Tell it; avoid mentioning its extreme rarity. Then will humbug have its perfect work, till a district that should of rights be a national park is regarded as the national slum.

The district is picturesque, however. It has nooks where mountaineers celebrate “old Christmas,” Gregorian style, on January 6, and at midnight on old Christmas eve “the alders bloom, and cattle kneel down. Hit would make you mighty solemn to see them kneel; you wouldn’t feel like beatin’ on them no more.” Along many a highway drivers still keep to the left, as in England. Hand-made textiles and hand-made baskets perpetuate classic English designs. An occasional singing-school still uses “shaped” notes, with do, re, mi differing not only in their position on the staff, but also in form and semblance. A few tables, a very few, still sport the “lazy Susan,” a kind of merry-go-round for eatables. Once in a great while you will see a mountain wife perched behind her husband on a mule. And the language! They “carry” a horse. They pamper the “least” child. Desiring a “preacher-parson” to say grace, they bid him “wait on the table.” From Possum Trot to Still Hollow it is “two good looks and a right smart walk.” What a hunting-ground for local color and the wherewithal for humbug!

As each peculiarity exists somewhere in the mountains, humbug feels free to make each particular mountaineer a museum of them all, a “type” so “typical” that his own mountains would scarcely know him. Whereas he is not struggling to epitomize and illustrate 112,000 square miles. He has other interests in life. Whole paragraphs he will talk to you without once lapsing into “Shaksperian English,” although to my personal knowledge the Shaksperian words commonly used in the mountains number at least four: “buss” for “kiss,” “poke” for “bag,” “poppet” for “doll,” “holp” for “helped.” As well might you call it the English of Burns, since the “beasties” in “yon” pasture “want out.” Or why not the English of rural Ohio because of “hain’t,” “colyume,” and “gardeen”? By the same token, call it Montanian because of “pack” for “carry,” or Chaucerian because “hit” replaces “it.”

The lowlanders likewise say “hit,” but let us not reveal that. Inspired ethnologists, let us consider the mountaineers a race apart and dwell lovingly upon such idiosyncrasies as “sun-ball,” “church-house,” “rifle-gun,” and “man-pusson.” Especially let us cherish idiosyncrasies which, though too few to make a patois, are deceptive enough to make trouble.

Page 397: mou_0003

The Mountaineers: Our Own Lost Tribes, illus. 4. [mou_0013.jpg]

Imagine an artist’s state of mind when a mountaineer said to him, “Your little old woman ‘s the stoutest I ever saw,” or a clergyman’s on hearing himself described as “the commonest preacher,” or a teacher’s when the mountain people exclaimed, “You don’t care to work.” Nevertheless, these were compliments. Translated, they become: “Your charming wife is very athletic,” “You preach so that every one understands you,” “You are not afraid of work.” At a box-party (not theatrical) a girl from Denver said to a mountain lad, “Come and talk to me.” Shocking! In the mountains this means, ”Come and make love to me.” But reflect. Two centuries or thereabouts mountain English has lived withdrawn from the world. On the whole, it has improved. It scorns slang. It is innocent of stereotyped phrases. Out of the abundance of the heart the mouth speaketh and in its own individual way. For instance: “I do crave to quit tippin’ the bottle, but I can’t get the consent of my mind.”

May Appalachia forgive me if these examples make the highlander seem queer. Queer he is not. Hear his observations in the cabin or at the mill on grinding day or around the temple of justice during court-week. Few and far between— hardly noticeable, in fact—are his oddities of speech. Talk ripples on softly, pleasantly, in the verbiage of the rural South, or perhaps of the urban South. Fine little cities dot the mountains. There is Asheville. There is Charleston, West Virginia, to say nothing of Chattanooga. If by “mountaineer” you mean anybody living in Appalachia, then some curious anomalies turn up. Mountaineers thronged to see Mme. Bernhardt ! Our driver on a never-to-be-forgotten trip through the mountains wore low shoes and lavender socks. But the very wilds and deeps of Appalachia afford proof that there are mountaineers and mountaineers. In fiction, however, reference is had to the latter only. In travelers’ tales you meet a homogeneous race of “mountain whites.” Whites, indeed! As if these proud, sensitive, ancestried pioneers had anything in common with the “po’ white trash!” Come, come, let us keep things separate!

In the eighteenth century — just when no one knows — Scotch-Irishmen, a few Germans, and fewer Huguenots entered Appalachia and peopled its valleys. Their tribes increased. Sons of original settlers established themselves on the lower mountain-sides. Their tribes increased in turn. At last even the wildest, most inaccessible coves became inhabited. Conditions varied and do still. There is prosperity in the fertile valleys, moderate comfort along the lower mountain-sides, dire and heartbreaking misery here and there in remote fastnesses, illiteracy, too, and sometimes savagery. Moreover, the first-comers were not all alike. Some were farmers, some professional hunters, some adventurers, some fugitives from justice at a time when the law meted out terrible punishment for offenses now considered trivial. Social distinctions of a sort existed at the outset. They have sharpened. In the mountains one hears of “good stock” and “bad stock.” Repeatedly one hears the warning, “Don’t think we are all alike.”

Page 398: mou_0004

What mortal in his senses would expect them to be? Bloody Gulch, Idaho, is not like Helena, Montana, and there are twice as many people in Appalachia as in the whole length and breadth of the Rockies. Cape-Codders are not like New-Yorkers, and Appalachia is bigger than New England, New York, and Delaware combined. Nevertheless, I will risk showing you a typical mountain region—typical in that it sums up pretty nearly all the mountain conditions to be found anywhere. “Back” your horse, say your prayers, fix your last thoughts upon your family. We are off. Along roads splendidly wide and along roads so narrow that when two vehicles meet one stops, sheds its horses, tips up on its side, sheds its uppermost wheels, and lets the other vehicle go by; along roads blasted from the very rock, and roads that are more like cornices, and some that follow a creek, now on this side, now on that, fording it every few rods. Presently the creek is the road; splash, splash, goes your horse, up-stream or down, for perhaps a hundred yards. But look! listen! Yonder a train piled high with logs pants along a narrow-gage railway. Though logging will cease by and by, the narrow-gage will remain.

Such, in sober fact, are these “impassable” mountains. Automobiles come, and motorcycles. Forty-five miles from a railroad a circus appeared. Mountaineers still point out trees to which the elephants were chained. A single county in a single year voted ninety thousand dollars for good roads. If I hesitate to recommend the mountains as a continuous speedway for Sybarites, if I admit that in wet weather wheels sometimes go axle-deep, and if I report trails through wild gorges where no road could live a month and lost fastnesses without even a trail, I am only proving what I set out to. Mountain neighborhoods differ. The bridges show it as clearly as the roads. One sees primitive foot-logs, just as the novelists say. As the novelists avoid saying, there are also bridges of concrete and steel. Strange enough such modernities look in a landscape strewn with “typical mountain homes.”

Ah, those “typical homes!” Window-less, one-room horrors, with open chinks between the logs and with chimneys either of stone or of sticks and mud. Well may the inhabitant “sit in the chimbly an’ spit outdoors”—save for one fairly important detail; that is, nobody lives there. Abandoned for years, these “typical homes” enjoy at present the status of ruins. To see such hovels inhabited, (and they still are in many an unfortunate neighborhood) you must generally force your way to some aery of a place peopled by the submerged. If this sounds paradoxical, never mind. The higher, up you go, the lower down you get.

Then what, in common honesty, is a “typical mountain home”? We pass two-story frame-houses, set side toward the road, an exposed brick chimney at each end. We pass commodious log dwellings with lace curtains at the windows and flowers blooming in the dooryard. We pass cottages which, given the gingerbread frivolities they lack, might suit a vacationist. It sounds incredible, but we pass three huge, pillared mansions. The type? None exists. Nor can you find anywhere the “typical mountaineers” ranged in stiff rows before their dwellings and making the “typical” sour faces.

They do it systematically in the photographs, and very oddly it strikes one to see them about their business in real life, swinging terrible, Roman-looking, double-edged axes, or strolling the wilderness, rifle on shoulder, or toiling at farm-work on slopes so precipitous that a man may “break his leg falling out of his cornfield,” and the only way to plant is “with a shot-gun from the opposite slope.” No nonsense can exaggerate. In such places a wheeled vehicle is useless; nothing but the low wooden sledge will keep right side up. To think that men till these cruelly upturned acres and still have a ready smile and greeting for the “furriner”! Gentle, winning, and hospitable, they hail you with a “Howdy, stranger! Light

Page 399: mou_0005

an’ set. What mought your name be? What mought your business be?” Between women the exchange of civilities may begin: “How old be you? Be you married? How many children have you got? I hain’t got but ten, myself. Hit seems like a body ought to have at least a dozen.” Forthwith they invite you to stay all day, which leads to your staying all night, which leads to your staying half the next day. It requires no tact to get into a mountain home, but it takes both genius and self-denial to get out.

Although fortune has acquainted me with several good dinners (in the mountains “several” means “many”), a dinner at Paul Jefferson’s ranks with the best. As for Paul, think of John Burroughs, John Muir, John Burns; then shut your eyes, and you will see that magnificent patriarch.

What a host is Paul! What a hostess is Mrs. Paul! She will spin for you, smiling as she spins. She will weave. She will present you to Ann of the rosy cheeks (a living Perugino) and to “blossom-eyed” Elizabeth and to half a dozen stalwart sons. In college togs instead of homespun suits, immense black slouch hats, and leather leggings, they would pass for nabobs.

Exceptional all this? Such a household would be exceptional anywhere. But choose a log cabin at random, the poorest, even. You will meet the same geniality, the same gentility. However, you will miss the glowing faces. With privation and hardship come premature wrinkles. Much that seems to indicate longevity among the mountaineers indicates only the early havoc of youth. There goes a story about a “furriner” who found an old, old man weeping by the roadside.

“Why do you weep?” inquired the stranger. The “old, old” man replied:

“Daddy whipped me for sassing grandma.” It is a foolish yarn, confessedly, yet not without its specious grain of truth. The haggard, wrinkled countenances you see in photographs belong often to mountaineers whom struggle, not time, has aged.

Nevertheless, the impression one gets in the mountains is of a race exceptionally strong and energetic. Their farms languish, but not by reason of “shiftlessness.” Antiquated methods, a depleted soil, and the interminably long road to market keep agriculture in the doldrums, or frequently do, and the mountaineer content “jist to rock along.” He works off his surplus vitality by tracking a fox; he climbs three successive ranges to visit a friend; he stays out till dawn if a possum invites, and tramps home re-freshed. During the Spanish War the tallest, heaviest soldiers came from the mountains. Revolutionary patriots marched to Massachusetts in twenty-one days. During the War of 1812 mountaineers reached New Orleans without weapons, but in such spirits that they declared, “We’ll foller them Tennesseeans into battle, and every time one falls, we’ll jist inherit his gun.”

Theoretically, mountain life fosters health; practically, it is sometimes fairer to say that health survives despite mountain life. Hair-lifting tales one hears of three-year-olds munching tobacco, of infants dosed with whisky (“Maw she drinks hit,

Page 400: mou_0006

too, an’ gives hit to the baby to see hit act quar”) ; and in isolated cases such tales may be true. Whole districts lack a physician to teach even the a-b-c’s of hygiene; certain others “suffer less from the absence of physicians than from their presence.” In the least-favored regions cookery kills at forty paces. After a meal in a cabin twelve miles from nowhere, Mr. Horace Kephart wrote passionately, “What the butcher ruined the cook damned.” Yet I challenge Christendom to produce a finer, hardier, wirier stock than these highlanders.

Or a more interesting stamp of character. Lincoln’s parents were Appalachians. So were Daniel Boone, David Crockett, Sam Houston, Andrew Jackson, James K. Polk, Andrew Johnson, “Stonewall” Jackson, and Admiral Farragut, not to mention such notables as General Love, Congressman Green Adams, Governor Woodward, and Justices Samuel F. Miller and William Pitt Ballinger of the United States Supreme Court. What a showing by the region for which Senator Blackburn prescribed dynamite!

The honorable gentleman objected quite properly to feuds. Yet feuds, too, were honorable. A heritage from Scotland, they continued among clans that are “still living in the eighteenth century.” Men slew for conscience sake. Even the occasional crime of violence outside the vendetta counties has its honorable points. Unwritten law not only permits a mountaineer to avenge wrong, but requires him to. Unhappily, “mountain dew” will sometimes bring down vengeance too hastily in this “land of sunshine and of ‘moonshine.’”

Personally, I detest moonshine (what little there is of it to detest), but respect moonshiners. Middle-Westerners turn corn into hog to make it portable; with the same object a very limited class of mountaineers turn corn into whisky. In districts where it would cost more than the corn is worth to get it to market “blockade” goes out at a profit on the “blockader’s” back. Tourists, even remarkably good tourists, hoodwink the customs officer if they can. Rebelling against what appears to them an oppressive law, moonshiners outwit a revenue officer if they can. At a pinch they may shoot. Oftener, when “ketched,” they jeer the marshal. Quoth “Atch” Young (christened Achilles, but subsequently abbreviated): “Say, Captain, hit tuck a heap of elbow grease to get that still set up, an’ really hit’s a mighty sweet-runnin’ consairn. If hit won’t make hit wuss fer us, let’s run a pint or two before you cut hit up.” From Buck Towner you will hear that “when folks get word that the marshals are comin’, they put stuff in hit to pizen hit. The marshals allers do take as much as they want, an’ the pizen makes ’em so they cain’t crawl around for over a week.” One blockader regularly exacts tribute for betraying a still. Aside, sotto voce: the still is his own.

Were moonshine particularly plentiful,—and the novelists imply that it trickles from the very tree-trunks, anywhere and everywhere,—a “fotched-on furriner” like yourself might fancy the mountaineers quite habitually drunken. On the contrary, they are quite habitually “nice.” Dare I say it? They are curiously like the rest of us. They have their faults, not worse than ours. They have also their shining virtues.

Mountain ethics present some oddities now and then, I confess. In certain rare neighborhoods, our Ellen Keys would behold their principles in full operation. But commercialized vice has no foothold among the genuine highlanders. Thieves, tramps, and gunmen are unheard of. Even feudists and moonshiners go faithfully to church. They tell of a highwayman who met a bishop and stripped him of his all. Said the victim:

“Don’t you think it ‘s a shame to rob a poor Episcopal bishop?” To which the bandit replied:

“What, you an Episcopalian? Take your money! I’m an Episcopalian, myself.” Remarkable, very, on the part of a highwayman who never existed! I can go alone anywhere in the mountains. A girl could. As a matter of fact, girls do.

Page 401: mou_0007

However, such legends die hard. “I drink an’ I swar an’ I’ve killed nine men,” says the hero of another; “but, thank God, I’ve kept my religion through it all.” To trust the common tale, there yawns a great gap between doctrine and deed. “Emotional, superstitious, unlettered, the mountaineer seeks the ‘church-house’ as naturally as his bees seek their ‘bee-gum.’ And just as devoutly.” It sounds logical. It is, nevertheless, a slander. Fifteen Protestant denominations (the mountains have virtually no Catholics) send educated preachers who urge the correlation of faith and works. If a share of the native preachers lack erudition, they have merits of a sort, despite that. Said one far back in the wilderness:

“Brethering, you’ll fine my text somers in the Bible, an’ I hain’t a-goin’ to tell you whar; but hit’s thar. Ef you don’t believe hit, you jist take down your Bible an’ hunt twell you fine hit, an’ you’ll fine a heap more that’s good, too.”

From the cultivated point of view, or the pseudo-cultivated, what a blind leader of the blind! Yet illiteracy is not incompatible with knowledge or ignorance with insight. The mountaineer inherits brains. Among highlanders who can neither read nor write, or among highlanders who at best will ask a school-ma’am to “back” a letter (that is, direct the envelope), you may occasionally find volumes of Horace and Vergil with the names of remote ancestors inscribed therein. Education has lapsed. Mental aptitude has not. It takes brains to make one’s own rifle; it takes brains to make furniture without nails or glue; it takes brains to make hempen-haired “poppet-dolls” of whittled wood; it takes brains to spin and weave and dye. Mentally, the “furriner” meets his match in the highlander.

Page 402: mou_0008

“Why don’t you sell this miserable patch of ground and get out?” said an intruder in Hell-fer-Sartain. His vis-a-vis replied:

“I ain’t so pore ‘s you think. I don’t own this patch of ground.”

In Europe we love the primitive and unspoiled. In America it shocks, and philanthropy unites with patriotism to bid us “poke the ‘eathen out.” Yet how eagerly we once read “La vie simple”! How we yearn for an escape from artificiality! The mountaineers have found both, and in what a setting, surrounded by scores of lovely, dim, blue peaks! You “can stand on the summit of Roan and tickle the feet of the angels.” From such a paradise the ” ‘eathen” decline to be poked out. As well ask the Swiss to leave Switzerland!

Some migrate, it is true. Misguidedly, they seek the mill towns, where aristocrats look down on “hands.” That stings. “I ‘m as good as you are,” says the mountaineer, “an’ I don’t eat at nobody’s second table.” He grieves to be a “hireling.” Opportunity may beckon, promising wealth and its advantages if only he will be patient; but what cares he? Pride, not inertia, inspires his declaration, “I don’t aim to rise above my raisin’.” Back he comes, like as not, reviling the twentieth century, belauding the eighteenth. A mountain woman, getting her first glimpse of our much-vaunted civilization, cried fervently, “I ‘d rather be a knot in a log on Perilous.” When you have seen Perilous [near Hindman, KY] and felt its charm, you will understand.

Prosperous farmers lack the incentive to migrate; poverty-stricken farmers lack the means. Where barter prevails, and the “least” child carries an egg to the store for an egg’s-worth of candy, a family may go a year without handling ten dollars in money. Move? Start afresh elsewhere? It is out of the question.

Given a chance at education, young mountaineers will deign to “rise above their raisin’.” They make insatiable students. The youthful Lincoln, doing sums on a snow-shovel in a log cabin, was not more determined, though it disgusts a mountain lad to be everlasting sentimentalized over as an Abraham Lincoln in embryo. Like Lincoln, he has the saving grace of humor. Indeed, I should think him perfect, and his sister, also, were it not for the haunting mockery of a scene I look back to as the prettiest I ever witnessed in Appalachia.

Around me the snow-decked wilderness a-gleam with enchanting sunshine. Below me the clouds. Among the laurel swift, darting flames that were redbirds. Everywhere a stillness broken only by our houses’ footfalls. Then, at a turn of the trail, laughter and merry greetings from half a dozen blue-uniformed school-girls on their way home, suitcases in hand, for the Christmas holidays. Forth they go, these young mountaineers, and back they come for vacation. As a rule, that is all. Observe, I am not generalizing too broadly, I say a rule. In my criticism, I reflect the opinion of mountain teachers themselves. Too often the schools drain the mountains of the brightest sons and daughters of the most ambitious families. Fitted definitely for success in the big world outside, and given no definite equipment whatever for success in the highlands, they drift to the cities. Take Ben Wentworth’s case. A promising young business man, he is an asset to Birmingham. Yet consider the loss to Possum Trot!

I pass no censure upon Ben. Nothing he learned at school would have enabled him to wrest more than a bare subsistence from the soil of Possum Trot. I pass no censure upon the school. It followed a time-honored tradition in regarding education not as an uplift, and as social uplift at that, but as the merest rescue-work. It saved Ben from the mountains. It let the mountains slide.

There are mountains in Appalachia that can safely be let slide. There are regions enviably prosperous. But on the other hand, there are regions that shriek to high heaven for uplift. Think of trachoma and no doctor. Think of a broken leg, and three days in a makeshift ambulance.

Page 403: mou_0009

Think of typhoid and tuberculosis, with no one to hint at prevention or cure. Think of district schools closed seven months in the year, if district schools there be, and pupils unable to read after several terms of so-called instruction. Think of squalor and misery and aching deprivation. Three hundred thousand mountaineers, adding one luckless neighborhood to another, live in wretchedness unspeakable. Our kinsmen, mind you; not hyphenates, but descendants of the original Americans. Appalachia furnished the rear-guard of the Revolution. It is through no fault of theirs that the three hundred thousand have fallen on evil days. It is the work of isolation.

Little by little isolation gives way before industrial inroads. New railways come. Lumbermen attack remote forests. Coal is discovered. Electrical engineers plan the damming of streams, the building of powerhouses. Resorts bring loiterers from highland and lowland. But contact with the outer world brings dangers as well as benefits. No one who has the future of Appalachia at heart wants to see it either invaded or evacuated. Everyone who has the future of Appalachia at heart wants to see it brought into its own. It ought from the first to have been a sovereign commonwealth. Failing that, it was gerrymandered among nine separate States, affording an admired, but neglected, back yard to each.

Lost tribes I call these mountaineers. Lost to America, I mean: several millions of our best people shut away whereas a race they contribute little or nothing to our modern progress. Individual persons emerge, it is true. Here and there a thriving town springs up, to link itself with America. Yet for the most part Appalachia lives in solitary confinement; in cold storage almost. And while a pre-Revolutionary America within an America is interesting and romantic and a joy to our novelists, solitary confinement and cold storage involve the handicapping of abilities. They insulate genius. They insulate talent. Both are as common in Appalachia as elsewhere. Both are waste material and remain so except as some random fortuity provides the outlet.

A vicious circle obtains. Without prosperity, no opportunity. Without opportunity, no prosperity. All praise, then, to the new leaders who have set about breaking that circle. They intend that hereafter the Ben Wentworths shall re-

Page 404: mou_0010

turn to Possum Trot. They will fit them to return and to succeed after they have returned. They are teaching them modern farming, the principles of improved housing, the niceties of enlightened hygiene. They are teaching them to teach others. They have adopted and applied the maxim of George Ade, “When uplifting, get underneath.”

“They needn’t send missionaries to us,” say the highlanders; “we ain’t no heathen.” No, and neither are these new leaders missionaries in any sense hither-to known. Money from denominational coteries supports them, to be sure, but they aim to abolish missions by bringing prosperity so that the mountaineers will before long have their own churches, their own schools. The motive is less benevolent than patriotic. It would “induct Appalachia into the Union” not for Appalachia’s sake, but for the Union’s. Their spirit resembles Dr. George T. Winston’s when he addressed a returning governor of North Carolina.

“Sir,” said he, “our welcome is largely selfish. We do not welcome you to our midst; we welcome ourselves to yours.”

GALLERY: “The Mountaineers: Our Own Lost Tribes”

- The Mountaineers: Our Own Lost Tribes, illus. 2. [mou_0001]

- The Mountaineers: Our Own Lost Tribes, p. 396. [mou_0002]

- The Mountaineers: Our Own, p. 397. [mou_0003]

- The Mountaineers: Our Own Lost Tribes, p. 398. [mou_0004]

- The Mountaineers: Our Own Lost Tribes, p. 399. [mou_0005]

- The Mountaineers: Our Own Lost Tribes, p. 400. [mou_0006]

- The Mountaineers: Our Own Lost Tribes, p. 401. [mou_0007]

- The Mountaineers: Our Own Lost Tribes, p. 402. [mou_0008]

- The Mountaineers: Our Own Lost Tribes, p. 403. [mou_0009]

- The Mountaineers: Our Own Lost Tribes, p. 404. [mou_0010]

FOR ADDITIONAL SCRAPBOOK SELECTIONS See:

SCRAPBOOK BEFORE 1929 Guide

LOCAL HISTORY SCRAPBOOK Guide 1920-1980

SCRAPBOOKS Guide

See Also:

SCRAPBOOKS – Overview

Return To:

SCRAPBOOK BEFORE 1929 Guide

| Title | “The Mountaineers: Our Own Lost Tribes” |

| Creator | Rollin Lynde Hartt |

| Alt. Creator | John Wolcott Adams (Illustrator) |

| Identifier | Permalink: https://pinemountainsettlement.net/?page_id=2903 |

| Subject Keyword | Pine Mountain Settlement School ; mountaineers ; Rollin Lynde Hartt ; John Wolcott Adams ; Southern Appalachians ; lowlanders ; highlanders ; Shakespearian English ; mountain English ; Scotch-Irishmen ; Germans ; Huguenots ; narrow-gauge railways ; Paul Jefferson ; Horace Kephart ; moonshine ; Achilles Young ; Buck Towner ; marshals ; blockaders ; religion ; illiteracy ; philanthropy ; patriotism ; migration ; mountain women ; Ben Wentworth ; |

| Subject LCSH | Settlement Schools — Harlan County — Kentucky. Pine Mountain Settlement School — Harlan County — Kentucky. Education, Rural — Kentucky — Case studies. Big Stone Gap — VA. Appalachians (People) English language — Spoken English — Appalachian Region, Southern. English language — Dialects — Appalachian Region, Southern — Glossaries, vocabularies, etc. Mountain life — Appalachian Region, Southern. Americanisms — Appalachian Region, Southern. Appalachian Region, Southern — Description and travel. Appalachian Region, Southern — Social life and customs. Figures of speech. |

| Description | Published as vignette in: “The Mountaineers: Our Own Lost Tribes,” by Rollin Lynde Hartt, The Century Magazine. January 1918. New York (95:3): pp. 395-403. |

| Publisher | The Century Magazine. January 1918. (95:3): pp. 395-403. |

| Contributor | n/a |

| Date | Date of article: January 1918 ; Date digital: 2008-10-10; |

| Type | Text ; image ; |

| Format | Article removed from original publication. |

| Source | Series 27: Scrapbooks, Albums, Gathered Notes |

| Language | English |

| Relation | Series 27: Scrapbooks, Albums, Gathered Notes ; See http://toto.lib.unca.edu/collections/periodicals.htm for additional periodicals in the same genre. |

| Coverage Temporal | 1918 ; |

| Coverage Spatial | Southern Appalachian mountains ; |

| Rights | Any display, publication or public use must credit Pine Mountain Settlement School, Pine Mountain, KY. Copyright retained by the authors of certain items in the collection, or their descendants, as stipulated by United States copyright law. |

| Donor | Virtual |

| Acquisition | n/a |

| Citation | Pine Mountain Settlement School Collection, Pine Mountain, KY. |

| Processed by | Helen Hayes Wykle ; Ann Angel Eberhardt ; |

| Last updated |

2008-10-10 hhw ; 2013-11-11 hhw ; 2014-07-08 aae ; 2020-06-11 hhw; 2023-08-08 aae ; ; Sources Hartt, Rollin Lynde. “The Mountaineers Our Own Lost Tribes.” The Century Magazine. January 1918. New York (95:3): pp. 395-403. Series 27: SCRAPBOOKS. Pine Mountain Settlement School Collection, Pine Mountain, KY. Archival material. Bibliography |

| Bibliography | Hartt, Rollin L, and John W. Adams. The Mountaineers: Our Own Lost Tribes. New York: Century Co, 1918. Print. Hartt, Rollin L. New York the National Stepmother.. NY: The Century Company, 1917. Illus. by Lester G. Hornby. 13pp Extract salvaged from a damaged issue of The Century Magazine, Volume 93, No. 3, January, 1917. Print. Hartt, Rollin L. Rollin Lynde Hartt Papers. 1896. Print. Hartt, Rollin L. The Woman Physician: Has She Arrived After Her Long and Adventurous Struggle. New York: Century Co, 1927. Print. Hartt, Rollin Lynde. The Man himself. 1924. Levy, Felice D. “Hartt, Rollin Lynde: 72.” Obituaries on File. (1979). Print. |