Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 09: BIOGRAPHY – Visitors

“Untamed America”

Article by Percy MacKaye

6 pages, copyright 1924

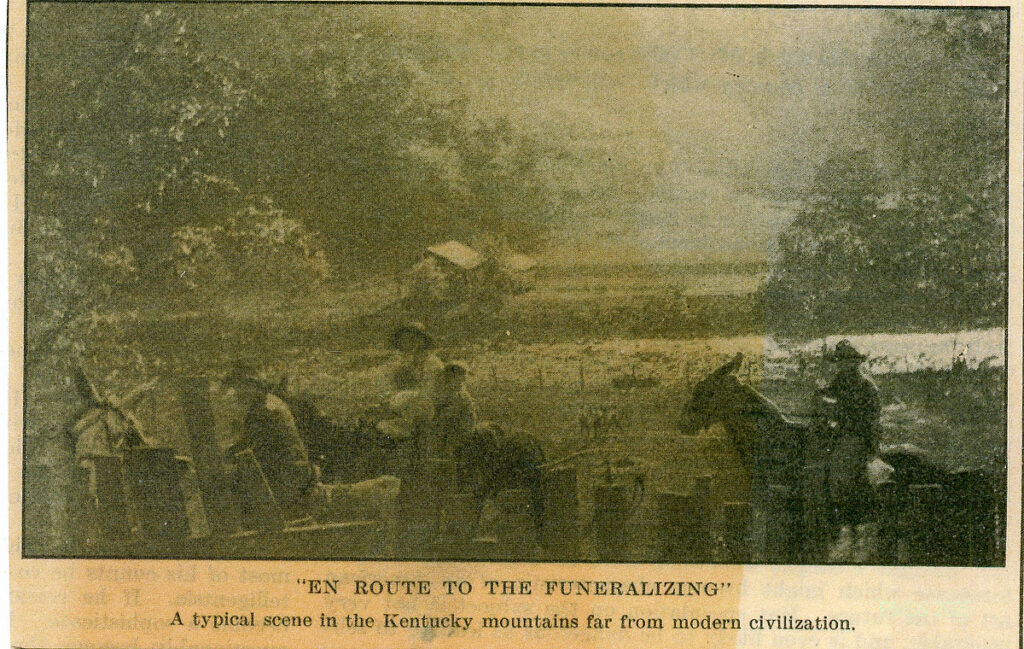

“En Route to the Funeralizing.” [mackaye_on_way_ro_funeralizing_001.jpg]

TAGS: Percy MacKaye, PMSS visitors, Untamed America, pioneer spirit vs modernism, poet-dramatists vs methodical educators, conserving the spiritual wild nature, exuberant social sense of mountain life, mountain dialect, poetry in illiteracy, old John Shell, old Sol Shell, natural diversity vs national standardization, definition of untamed, oral imagination of the mountaineer, the policy of Reciprocity

TRANSCRIPTION: PERCY MACKAYE VISITOR “Untamed America”

001 [MISSING]

002

UNTAMED AMERICA

…involving the Untamed and Tamed — the Pioneer Spirit of America wrestling with the Machine of Modernism to retain his elemental plasticity unfettered. And everywhere I have beheld the Machine downing that valiant Wrestler, whose sinews grow ever weaker in the struggle. Everywhere, however, I have observed an increasing awareness of the issue, and a deep longing on the part of some leaders (pioneers of the future) for its human solution.

The pioneer is twin-brother to the poet. The Kentucky mountains are still peopled with ancient pioneers. The pioneers of a new education — may they not find a fraternity of helpful understanding in the more intensive study of that poetic civilization which their unfettered brothers of the hills still have to contribute to that great Wrestling Bout before the Machine levels them to a common impotence?

This article can only suggest, not develop this large theme. Drama and poetry are of the essence of education, but the method of the poet-dramatist differs essentially from that of the methodical educator.

During my travels in the mountains I collected, with my wife’s aid, several volumes of original data concerning the language, thought, tales, songs, superstitions of the mountain people. These conceivably might be put to purely scholastic uses. For my purposes, however, they are simply loam of an authentic subsoil for the growth of a native Theatre of Poetry, to which I hope slightly to contribute in a group of plays. The growth of such a Theatre may well become part of a policy of Greater Conservation. Such Conservation, I suggest, if it is to be worthy of its American birthright, will not stop at salvaging merely our backgrounds of physical wild nature, its power-waters and forests with their diversities of bird and plant life. More vitally important to its human goal, it will become also a conservation of spiritual wild nature, with its precious diversities of Man — his distinctive species of soul-life, his unspoiled heritages of thought and untamed imagination.

Their oneness with wild nature is integral to the character of the mountaineers. While we were gathering data for the plays, my wife recorded some of the characteristic backgrounds in a trail-journal, from which I shall quote in this article. Here is an excerpt:

“A hard, steep climb in the rocky bed of the creek, straight up to the top of the mountain. The trail was wild with a rich, dank beauty. Fallen logs, moss-grown and lichen-covered, lay thick like shaded jade, exuberant in greens with rich golden- brown and heavy blue-black depths. The sunlight, falling through the luxuriant, overhanging branches, cast the carved shadow-patterns on this jewelled forest floor.

“Emerging to the open skyline after the last steep pull, we came upon the narrow margin of the mountain-top, just wide enough for a rail-fence, mountain-fashion, zig-zag, and the slender trail. There — plunging on ‘yan side,’ as the natives say — swept downward the surging sea of corn, all in blossom, with shining blades. It was a mighty field of ranked industry, every line even, and now and then, like ‘hants’ among them, rose the ominous gray, twisted limbs of the girdled trees, dead-years gone by, but still wasting away in ghostly accompaniment to the eerie folk-lore of ‘Old Granny Big Poll’ and her eldritch Cats!

“Here we stood leaning against the fence-rail, gazing far down below to the bottom of the cornfield toward the tiny cabins so far away. We walked for a few rods on level ground — a restoring occupation — then down we began to go, till the cabins hove in sight: little gray log-cabins with their garden-patches, the inhabitants coming to the door and gazing up at us — a rare sight for them — then on down again sheer to the creek, where we crossed on a slatted log and entered a paling.

[Photograph: “A master fiddler of the hills”]

“It was the prettiest place we have yet seen, rich with a profusion of blossoms and tall, lavender clusters of ‘church bells,’ where a most beautifully rough-hewn, weathered old smoke-house stood in the midst of a riot of Pretty-by-nights, Touch-me-nots, Moss Roses (our Coreopsis) and Princess-Feathers. Leading out to a chain and bucket on a windlass was a covered porch. Here we were greeted by a gray-haired mountain-woman, handsome and blue-eyed, an aged ‘Aunt Rachel’ by the well! After chatting awhile, we went on through her garden patch.

“Then along by the creek to an idyllic little hollow where the stream meandered, the geese and ganders…

003

UNTAMED AMERICA

…disported themselves, the tow-headed children wandered fancy-free, and the gentle heifer, with the sweet-echoed cowbell, strayed from dripping penny-royal to spiced mint.

“We hopped and poised and plunged and essayed ‘the brimming river,’ till a dingy domain greeted us with ‘What’s your name?’ from a rear window, half boarded up, where peeked a woman with the shadow of a man behind. Mistrusting it was a ‘Tiger,’ a window where you pass in your money and are handed out your bottle — we sedately stated our names — where from, and where going — and leaped on up-stream.

“Crossing only to re-cross, we reached before long a most primitive cabin, just beyond a splash-dam, with only a chicken roost for steps leading up to the door. We stopped to see if anybody was around, but only a fat little yellow kitten assumed the dignity of hospitality and demurely posed on the doorsill — a tiny atom of mountain life against the black emptiness of the windowless cabin — so soft and sweet she was, and so diminutive to be the only one ‘at home’ !”

These are the lonely backgrounds from which the “lonesome songs” take their strange cadences of isolation. But these represent only one aspect of the mountain life, which reveals its exuberant social sense in the riotous frolics and fiddle-reels of the puncheon floor, political oratory of the outdoor elections, and crowded gatherings of the countryside for the unctuous “Amens” and tears of funeralizings. To one of those preachments we were guided by a fine, mountain-born lad named Ray, as we travelled mule-back up an almost inaccessible “branch.”

[Photograph: “A mountain patriarch ambling to the grist with corn”]

“From all the cabins were now coming the mountaineers and wending along with us, the women sitting side-saddle behind their husbands, who occupied the saddles. The gathering grew and, as we started up the last steep incline, we were part of a Chaucerian pilgrimage, laughing, joking, bobbing and jostling, stirrup to stirrup on the vari-colored mules — children, courting couples, hill-folk young and old, barefoot and brogan — and among them, the jolliest of them all, ruddy faced, white-haired and moustachioed, was the mountain preacher, Uncle Charlie, all en route for the funeralizing of old Betsy, who had died some three years before, but was now having the obsequies, as it is often not convenient or possible to obtain a preacher here for months at a time. Often the widower is married again when the ceremony for the first wife is celebrated.

“The hillside was a veritable precipice, and one of the girls fell off behind and was caught just in time by her husband. What keeps them on, heaven knows! — just balanced on a mule’s slippery backbone on a still-more-…

[Photograph: “A granny of the creeks, homeward bound from a “workin'”]

004

UNTAMED AMERICA

…sliding meal-sack.

“At last we tied our mules with others in the creek, and got over an eight-rail fence –we all did, young and old for there are few gates here, and it is all in the day’s work. There, just as we essayed the fence, we heard the first high-wailing notes, drifting off across the hills, of the mountain preacher — that strange intoning which rises to a piercing yell, with deep drawing-in of the breath and nasal inflection: a sing-song giving of the Gospel, with high shouts, mouth wide open, hands high in air and then held over the ears, to enable him to give yet louder range to his voice without damaging his ear-drums.”

In all these experiences, that which fascinated me most in my quest was the vividly imagined thought, and its expression in a speech of amazing freshness and plasticity, on the part of those who had been least affected by the outer world language of literacy.

The mountain dialect exists, of course, in all stages of deterioration, and it is quite possible to visit many quarters where its distinctiveness is weak or negligible. But at its unspoiled best, it is still a speech splendidly racy in colloquial charm and power, and as admirably adapted to an indigenous literature as the Scotch or Irish, of which indeed it is a kind of American “mutation” from a blending of those with ancient English stock. Especially its constructions vitally responsive to the ebb and flow of spoken (not written) thought — are as sensitive to natural rhythms as the speech of the ear-trained audiences of Marlowe and Shakespeare.

This language is a precious heritage of the mountaineer from a thousand years of folk-culture; yet so cramped is the standardized culture of the average normal school teacher (blissfully ignorant of the Elizabethans and Chaucer and “Beowulf,” not to mention Burns and Singe) that the first admonishment of the mountain child — who has braved lonely miles of storm-swept trails, humbly to “crave school larnin’,” is for him to “correct” and shamefacedly disavow his own ancient mountain speech in favor of the “grammatical rules” of a rubber-stamp education.

“Yea, Sir, hit war the first cold spell that come, right when the grapes is about all gone and the rest of the berry tribe, between the turnin’ of the weeds under and the dyin’ of food, and thar comes in a gang of jay-birds, and they fills the mind of the bird poetry.’

There is a sentence I wrote down from the lips of an old mountaineer. How would the average normal school graduate “correct” it by “grammatical rules” in a “composition”? (Are the images and rhythms of elemental nature admissible to a “correct” education?) Would the gracious charm of that old man’s speech raise an educated titter from the school benches, where the new generation is being solicitously “civilized”?

[Photograph of a woman, “By the old smoke house, amid a riot of blooms”]

And here, from our records, is an etching of a mountain storm, remembered after seventy years by the same speaker: “Onct, when I were a leetle feller, I seed a thunder-ball — the likes of a comet-star. Hit come along a big black cloud, lightnin’ shootin’ through and through. And the cloud split open, and hit blazed a ball big as a washin’ tub, which the valley was claired up and ye could see away-y back yander. Hit come straight-over Black Mountin, and thar hit busted — big a noise as a cannon — on the battlements. And thousands of sparks they was falling, like foxfire, when wet hit shines of a night and light enough to travel by: like black balls of rosin, and hit burnin’. And the star-ball hit split that-thar cloud same ‘s a big saw-log comin’ down the current; and hit were standin’ apart that cloud, which the storm shone through hit, and hit went jist as straight as a gun would a-shot a bullet from west to east. Sech rain I never seed fall in my life!”

To this aged poet of nature, whose master fiddling in the hills has rejoiced the hearts of four generations, I owe intimations of the values of synthetic life, revelations of quick sympathy with all sentient things, which I would not swap for any specialty of the universities. He first taught himself to read in middle manhood when, taken ill, he lay on his cabin floor, face upward to his close-held Bible, which — already knowing mainly by heart — he was able to decipher from oral memory. Fortunate for him (as also for other thousands of mountaineers) that his first literacy led him to the splendors of speech in the St. James Version. Yet before then his poetic gifts were bred of a noble illiteracy.

So all poetry is by its nature kinned to illiteracy; for its function is to quicken and perpetuate, through…

005

UNTAMED AMERICA

,,,the ear, those plastic elements of man’s spirit which were evolved long before the existence of writing and reading, and which those tend to stiffen and retard. So printing is merely a necessary evil of poetry, which really lives only in the voice and the oral imagination.

It is this oral imagination, and the memory it springs from, which endows the mountaineers with a living sense of the long continuity of human life — a sense that is almost lost to us who record life in memorandum books instead of in brain cells. Thanks to it, the intimacies of family anecdote and history live on vividly, not merely for one generation but often for six and seven, touched with colors of the fabulous as conversations are repeated from sire to son.

As I stopped one morning by the cabin of an old native, who was hewing fresh shingles from the split trunk of a felled chestnut tree, I heard from his lips (substantially as follows) this family anecdote. of an incident which befell on another morning two hundred years before.

I had asked him how he came to live there. “How come I to be here, gabbin’ with you, this day and time? I’ll tell ye. Hit’s all to blame of a parrot-bird.

“Ye see, my grand, great, great grandsir’ he lived in old Ireland, the town of Brooklyn, jist out o’ the way of the ebb and flow of the tide. His pap kep’ a shipyard thar-Godawful rich he war. The roads thar is rayed off in block squares, and he lived in the ‘jinin’ buildin’ to the King.

“Now Jim — that were his name, my Grandsir’ — he were about fifteen year old, I reckon.

“So, one mornin’, and hit purty in fall time, Grandsir’ Jim were awalkin’ to his work by the tide, and he went through a fine apple orchard — great-big of red and gold apples hangin’ thar, the road amongst ’em. And thar in the green leaves they was one apple were striped purple-red, round bright as the bottom of a big, clean tin cup, and hit danglin’ down. And he war jist retchin’ up his hand for to grab hit —

” ‘Hold thar! I’ll tell the King on ye!’

“He drapped his hand, quick off.

” ‘Who hollered that?’

“And lo, behold, hit were a parrot-bird, the King’s watchman, settin’ thar in her golden cage for to spy who should rob the ripe fruitses. And thar she set slickin’ of her fashetty feathers, pieded red-scarlet and green and yaller-gold, and the blue hackle of her beak combin’ of her proud tail-piece.

” ‘Ho, pish to ye! Jist a parrot-bird!’

“Jim retched up his hand agin and grabbed the apple off.

” ‘I’ll tell the King on ye!’

” ‘I’ll kill ye if ye do!’

“Away went the King’s messenger and told the King, and back she flew agin.

” ‘I told the King on ye.’

“Then Jim picked up a stone and killed the parrot- bird dead as four o’clock.

“So hit went out agin him, the King’s warrant, which hit was death, or leave the country in three days.

“And the news of hit come to his pap, the shipmaster, and he axed the King of his pardin.

” ‘No, sirree!’ says the King. ‘No pardin for the one what has killt my watchman.’

“Then his pap. he says to Jim: ‘Jim,’ he says, ‘ye’re bound to leave here, or die. Leavin’s better than dyin’,’ he says, ‘so git out and go to Amerikee. Hit’s a wild country thar, but be a good boy and come back when ye kin.’

“And he put Jim aboard to one of his ships and paid his way acrosst the big water; and his maw, Rebeccy, grieved herself and died away soon arter then.

“So Grandsir’ Jim he come to port to the city of old Richmond in Virginny. But he never didn’t git back home no more. But he transmigrated through Verginny, and laid out in the Revolution war. he come through to Kaintucky on the south-west trail, and come in here at the head of the Beech Fork and settled on Cutshin — the first man ever lived thar, and he war buried thar in A-prile, 1777.

“Yea, Sir! So ye see hit’s a parrot-bird what’s to blame of me gabbin’ to ye here now!”

His store of such family biography was not limited to the “grandsir'” who came to America, but included the main line and cross connections of his intervening forebears in a rich flow of specific personal anecdote. To him some of these were as vivid in vicarious memory as the remembrance of his own mother and immediate family. In the mountains death is not a guillotine to dissever human relationships with instant oblivion. There personality sets through a long colorful after-…

[Photograph: Following the midsummer lure of the highland trail.]

006

UNTAMED AMERICA

…glow of memory, by the contemplation of which new lives of the tomorrow are touched and influenced. There is leisure for such contemplation. So the retrospections of a century shuttle through thoughts of today and are handed on to childhood. Occasionally they are summed up in a single individual, as in the case of “the Oldest Man in the World,” old John Shell, Senior, of Big Laurel, reputed to be one-hundred and thirty-three, whom I found at his cabin still lively and humorous, the agile father of an oldest son up in ninety and a youngest (by a new wife) aged seven.

In direct touch with this long, living past, the mountain children are reared, most of the year, in the out-door, all-around work of the soil, synthetic in its development of mind and body; and during the indoor months, they are intensively tutored in that unsurpassed college of oral imagination — the winter log-fire: a college also of nobly simple good manners and gracious hospitality, where — even in a one-room, windowless cabin, crowded with four generations — the stranger is always given a whole-souled welcome, in which the gentle voices and high-bred demeanor of the children reflect the schooling of their elders.

Here, in the university of the lighted “log-heap,” over the department of Humorous Fantasy, in the region of Greasy Creek, there presided till recently for almost a century the genius of a Santa-Claus-Munchausen in the person of “Old Sol” Shell (brother of the “oldest man”), whose oral annotations on the history and science of “The Pumping Sow,” “The Inverted Lightning Stroke,” “The Meat of a Snow-Ball,” and other indigenous chronicles, have helped to graduate some scores of lesser disciples, with eyes equipped with telescopic lenses for the wonders of nature.

Here, in the departments of Music, Drama and Dance (all departments being radii of the glowing hearth-circle), the home-scholar is subconsciously educated in the lyric cadences of the traditional Lonesome Tunes, in the choral rhythms of the old dancing Fiddle-Songs, in the deft improvisations of Present-day Ballads, celebrating the dramatic events of local history, and in the Play-Party Games related to these.

Here, too, in the seminar of the Haunting Uncanny, the flickering fire-shadows unfold to spellbound listeners the plots and psychic mysteries of such lore as might provide some reborn Poe with new masterpieces of weird tales. Some of these I heard and recorded at the cabin of an old school- master, a nobly upstanding man of rugged dignity, whose schoolbench “larnin’ had not adulterated the rare savor of his log-fire rearing. Some others I heard from incomparable “Aunt Marthy” — her of the ancient mountainy charm, up in seventy, the whip-tongued scourer of witches and charm-doctors — Aunt Marthy of the eternal tang!

Such tang and savor — how shall one describe them? They are ultimate desiderata, yet how shall they be defined and tabulated? What is the analysis of the taste of ripe cider — the savor of russet-pear, or of citron? The mountain tales, music, songs, the time-wrought characters — these cannot be adequately recorded or assayed in an article. The mountaineers are validly themselves. The charm, the rhythm and gusto of the singing personality which pervades their civilization cannot be pigeon-holed in print. It springs from untamed wild nature, which has nurtured that older civilization by intensively cultivating Natural Diversity as opposed to National Standardization. The contrast with our modernism is obvious and poignant. The issue of the contrast is imminent and of great import — to both.

In education and industry shall we show toward the mountaineers the same imaginative obtuseness which we have shown, to our own impoverishment, toward the splendid diversities of Indian civilization? Must the untamed become basely tame, or servilely imitative? Must their ancient variations so become extinct?

If so, let us not imagine we shall escape judgment by studying them in histories and museums. For the living species of the human spirit are far more precious to the future than to the past. By the revolutionary inventions of science, our planet is rapidly reaching the ultimate assessment of all its resources, physical and spiritual, for all time. What living ingredients then are to provide the factors of its future growth?

In spirit, as in bodily life, new growth can only spring from old stock. If the genus is destroyed, its species are lost forever. Not only the great auk is extinct: so are the Inca and (almost!) the Indian, with all their precious specialties of contribution to Man. Not only the upland plover is menaced with extinction: our upland brother of the Appalachians has not even the calculating benevolence of Game Laws to guard his untamed heritage.

Untamed does not imply undisciplined: it implies — not disciplined by another’s will from without. The Untamed has its own inner disciplines through the necessities of elemental nature. Its goal is the free individual. Contrasted with a tamed, materialistic society, an untamed, idealistic individualism is surely nobler: but far better and more sane is an untamed individualism which adopts, through imagination, the right means of social harmony.

What, then, is the right means in the case of the mountaineers?

Is it not the adoption of a New Conservation: a conservation which shall preserve the ancient Diversity of man’s spirit in order to develop from that a new Diversity to supplant our levelling Standardizations?

007

UNTAMED AMERICA

Shall we not begin at least by recognizing, respecting and utilizing the diverse store of oral imagination which the mountaineers have to contribute to our own need and paucity?

This, of course, our standardized education by the printing press ignores. But fortunately that oral imagination, richly developed in the mountains, is not always ignored by modern educators there. Notably the Pine Mountain Settlement School has set a noble pace in the conservation and revival of native balladry, not merely on the printed page, but in the living voices and memories of its mountain-born children. There, too, the ancient folk-dances have never ceased their continuity of a thousand years but are freshly building the health and beauty of the future. And there the looms and spinning wheels are plying the hardy hand-arts of our ancestors, as a progressive back-fire for the modern mechanizations of childhood.

Such an example for enlightened mountain education may well go further in championing the beautiful, unshackled speech of those highlands, till happily that gospel of home-rule shall so spread that every mountainy school-child, wherever he may be called to speak in the outer world, shall proudly boast the pronoun “hit” as his ancient birthright. For that “hit” is the little symbol of his uncontaminate heritage in a great folk culture, which hopefully may yet restore by its revival the sapping strength of the American Pioneer.

In this article I have purposely stressed these elements of salvation for the mountaineers (as also for ourselves!) — poetry, speech, thought, arts, crafts, imagination, unmechanized and untamed to servile imitations — because these elements are really the goal which even the mechanized still grope toward in their hearts and commend in their lip-service — else why not at once throw Shakespeare and the Declaration of Independence into the discard? I have stressed them also because they are not seldom ignored by those, equally in earnest, who see more vividly the impediments to their proper realization: the impediments, namely, of poverty, disease, unemployment, and aspects of ignorance.

To the devout ministrations of those who are working to ameliorate those evils in the mountains I pay my sincerest homage for their unselfishness. No admiration can be too high in that respect.

Yet, in order that those very ministrations may not — in succoring the mountaineers — destroy their distinctive identity, I would suggest that there is crying need for a plan, embracing large constructive policies, to cope adequately with the destiny of some millions of souls.

The first of these policies would appear to be Reciprocity.

The mountaineers are our fellow Americans. As we can offer them a new civilization, so they can offer us an ancient one, to match it.

As we can offer them competitive employment in the increase of human needs and luxuries, so they can offer us leisure unstriven for in the simplification of desires.

As we can offer them an anti-toxin for typhoid and the pox, so they — for worse plagues — can offer us an anti-toxin for servility and the mob.

As we can offer them literacy, with its hurly-burly of chaotic journalism, so they can offer us illiteracy, with its serenities of unintermittent thought.

As we can offer them the new arc-light of subjugated Nature, so they can offer us her ancient arc of stars and her untamed storms.

Here, then, are reciprocal civilizations.

Shall we enrich our own by destroying the other, or by conserving it?

Why shall we seek to “standardize” the distinctive good of either?

Why shall we not foster a creative conservation of both?

Why shall we not share, as united Americans, and build together for the future — each of his best?

Copyright, 1924, by Percy MacKaye

All Rights Reserved

GALLERY: PERCY MACKAYE VISITOR “Untamed America”

- 002 [mackaye_untamed_america_002.jpg]

- 003 [mackaye_untamed_america_003.jpg]

- 004 [mackaye_untamed_america_004.jpg]

- 005 [mackaye_untamed_america_005.jpg]

- 006 [mackaye_untamed_america_006.jpg]

- 007 [mackaye_untamed_america_007.jpg]

See Also:

PERCY MACKAYE Visitor 1921 – Biography

PERCY MACKAYE VISITOR Appalachian Play Reviews – Reviews of plays by MacKaye in various publications, 1920s; also, a review of a play by Hatcher Hughes.

PERCY MacKAYE and MARION MacKAYE VISITORS 1921 “God, Humanity

and the Mountains“ – Survey Graphic article by the MacKayes, published 1949

PERCY MACKAYE VISITOR and His Appalachian Creative Work [in progress]