Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 09: BIOGRAPHY – VISITORS in Residence

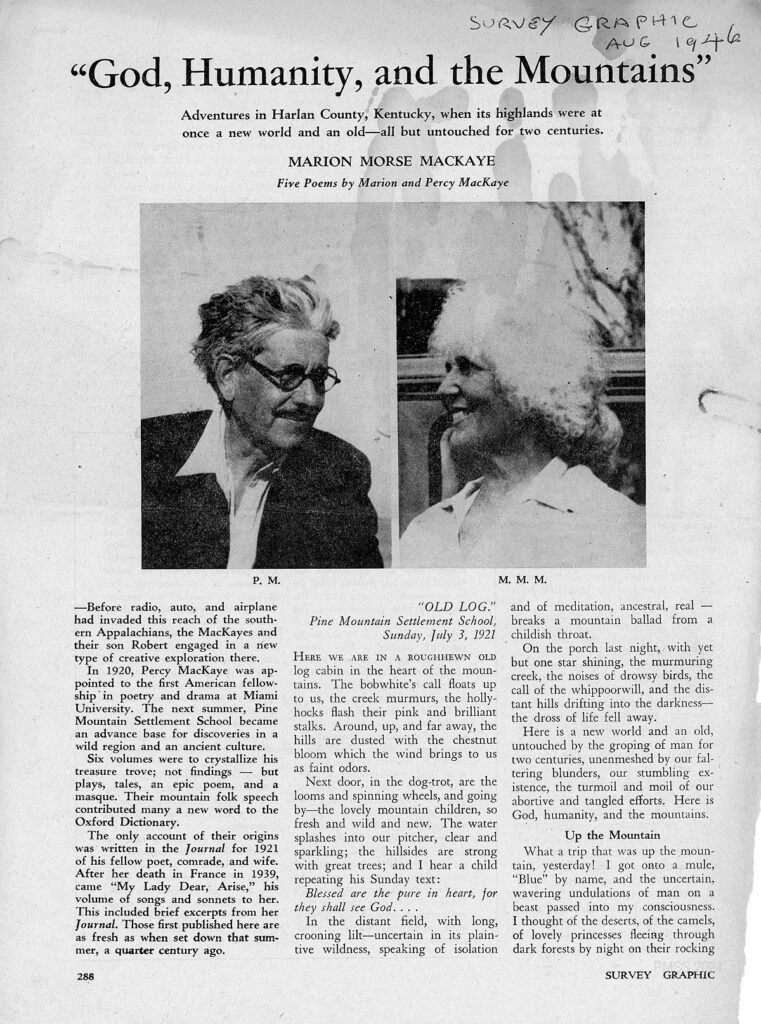

Percy MacKaye

Marion Morse MacKaye

“God, Humanity, and the Mountains”

In Survey Graphic, August 26, 1949

001 [mackay_god_humanity_mtns_SG-1946_001.jpg]

TAGS: Marion Morse MacKaye, Percy MacKaye, 1921, authors, playwrights, poetry, Appalachian history, New York theater, plays, pageants, funeralizing, preachment, poetry

PERCY MacKAYE and MARION MacKAYE VISITORS 1921 “God, Humanity and the Mountains”

The August 26, 1949 Survey Graphic article in the archive at PMSS, recounts the Summer of 1921 when the MacKaye family stayed at Pine Mountain Settlement School and traveled in the area gathering local lore. The stories of the family visit were recorded in their journals of 1921. This published article of Percy MacKaye in 1946, pulls stories taken from the couple’s journals seven years after the death of his wife, Marion. The reflections are vivid, touching, and were, no doubt, healing, for Percy and their son, Robin, who accompanied his parents during this magical summer.

- NOTE: Survey Graphic did not copyright all its issues. This particular issue, following due diligence to locate information, does not appear to be under copyright. If this is not the case PMSS will remove the article and attempt to locate permission.

Pine Mountain Settlement School. Path to the Infirmary (Hill House). Fall 2014. Photo: H. Wykle. [P1050514.jpg]

“Life is composition. There is your canvas.

God gives the colors; you design’

Now, what beauty will you assemble? —

“GOD, HUMANITY AND THE MOUNTAINS”

Survey Graphic August 1946

Adventures in Harlan County, Kentucky, when its highlands were at once a new world and an old — all but untouched for two centuries.

Five poems by Marion and Percy MacKaye

“OLD LOG”

Pine Mountain Settlement School

Sunday July 3, 1921

Here we are in a rough-hewn old log cabin in the heart of the mountains. The bobwhite’s call floats up to us, the creek murmurs, the holly-hocks flash their pink and brilliant stalks. Around, up, and far away, the hills are dusted with the chestnut bloom which the wind brings to us as faint odors.

Next door, in the dog-trot, are the looms and spinning wheels, and going by the lovely mountain children, so fresh and wild and new. The water splashes into our pitcher, clear and sparkling; the hillsides are strong with great trees; and I hear a child repeating his Sunday text:

Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God . . .

In the distant field, with long, crooning lilt — uncertain inits plaintive wildness, speaking of isolation and of meditation, ancestral, real — breaks a mountain ballad from a childish throat.

On the porch last night, with yet but one star shining, the murmuring creek, the noises of drowsy birds, the call of the whippoorwill, and the distant hills drifting into the darkness — the dross of life fell away.

Here is a new world and an old, untouched by the groping of man for two centuries, unemeshed by our faltering blunders, our stumbling existence, the turmoil and moil of our abortive and tangled efforts, Here is God, humanity, and the mountains.

UP THE MOUNTAIN

What a trip that was up the mountain, yesterday! I got onto a mule, “Blue” by name, and the uncertain, wavering undulations of man on a beast passed into my consciousness. I thought of the deserts, of camels, of lovely princesses fleeing through dark forests by night on their rocking steeds, as I swayed with Blue’s heaving flanks and sudden energy at rocky places. By mountain-pebbly streams, lofty cornfields, and little roadside cabins we wended; and then up over rocks and boulders into the forests, emerging into precipitous sides where, far off, the glorious just of mountains stood in blue haze. Turning again, still higher, new vistas opened and fresh ascents awaited us. Up — up — urging the mules and horses, twisting and grinding among rocks, tree roots, and fallen tree trunks till we reached the summit, the pinnacle where a fresh spring of such welcome water blessed our efforts.

There we sat resting for some time, the men who came with us — four of them — waiting for us and the mules to recover. Robin* cut us some stout sticks for walking, as it was too steep here for us to ride down. I shed my riding coat, as the heat was tropical. I don’t know if the men were startled with my Knickerbockers; I didn’t care. Robin helped me over the steep, rocky, sometimes muddy precipices, slipping and often running and leaping from rock to rock. He was my staff — Percy following on behind, talking of Rosalind.

* “Robin”: their son, Robert Keith MacKaye, Harvard ’23, then a junior at college. He is the author of “Honey Holler”, a play, and other published works, plays, and poems.

Again we mounted and on we traveled: such a journey of strenuous attempt, unusual surroundings, other world realities. I shall not forget the wild mountain, the caravan of mules twisting, scrambling in the forest glades and up the tortuous path; Robin striding along, Percy with his glowing eyes; the distant vistas, the rocking motion, the burning heat of tremendous endeavor; and then the last descent down the more cultivated slopes to Pene Mountain Settlement.

Going through the gate and stopping at our cabin door to enter — a miracle of loveliness, our home for the summer, so fresh, so sweet, so peaceful. The stream of life flows on. I watch it, see it, think of it, describe it and enter into it — still beholding it.

July 12, 1921

Percy wrote me a heavenly rippling, singing, fresh, bubbling brook song, this early, dewy morning: a mountain brook song, after a heavy storm-shower.

The Cloudburst

(To M.M.M from P.M)

Up through the sourwood

Under the white shingle-bloom

I can hear sweet waters

Chuckling, chinkling,

Chiming round the splash-dam

Down the dewy morning.

Yesterday and yesterday

In the drought bottom

You and I could hear there

Hardly a cheeping —

Only a thin trickle-drip

Droning through the laurel.

Till out of noon-dark

Poured the pent cloud-burst Smooching all the hollows,

Swallowing the mountains,

Wallowing the stepping -stones

Round our little cabin.

Now, dear, in the new day

Under the bridal-whit

Bloom by the old dam,

Hear the living waters —

Chinkling, chuckling,

Chiming through the laurel,

Rippling with the wrenny-bird

Down the dewy morning.

Neighbors

July 19, 1921

Last night, we spent the evening at Miss Pettit’s * and saw the moon rise, as the mountain children danced the “sets” on the dim green, with the dark wall of the mountain high behind them. They looked like pale will-o-the-wisps emerging and disappearing into the gloom.

As the moon arose up “yon side,” the light betrayed the edge of the forest, peering through the trunks of the trees and embroidering the mountain rim. Then its aurora bloomed a double rainbow and the disc soared rapidly skyward, flooding the valley with sifting, silvery mist, slanting down through the forest trees to glint the mountain brooks; and the whippoorwill made its eerie call, the katydid reiterating its hoarse denial of Katy’s actions with a staccato decision.

This morning we started for the cabin of Mrs. Dan Creech — who makes patchwork quilts — along the trail to Big Laurel, seeing the glistening laurel and rhododendron bushes against the deep green of the massed firs and tall, straight, sun-flecked trunks of perfect forest trees. We jumped and scrambled along the path, as it had recently rained and there were many mudholes, arriving at Mrs. Creech’s just as it began to rain. Hers was a gray cabin, windowless with the exception of a little peephole by the door, wall covered with old newspapers. Old Mr, Creech dozed in the doorway, his gray shaggy breast open to the flies which swarmed in …

p. 250

myriads. Hens scuttled in and out.

These cabins have blackened ceilings, sooty with the smoke of many years, old stone fireplaces, ancient wooden bedsteads covered with a variety of patchwork quilts, a hickory-split chair or two, loose floorboards that clatter up and down. On a rough set of shelves, usually between two beds, are stored the extra quilts which are the pride of the good housekeeper’s heart — and hanging from the ceiling by wires are the best clothes of the family, safely bestowed against the wandering rats. There is generally an old discolored-dialed clock which twangs the hour, and often a sewing machine and quilting bars.

We stayed till the rain stopped, Mrs. Creech and I in the kitchen, a cabin back of the main one where she had an iron step-stove. It went up in three steps, well adapted to her wood fire and the simple cooking. She made a cake and corn pone; cooked some beans with lard and pork; made some bean-coffee; fried onions and added flour and milk; and served us to apple sauce. I sat on a soapbox.

We ate our dinner to the intense squeaking of a young shoat under the boards at our feet, the hens picking up the crumbs under the table and the cat jumping up on top of it. There were no excuses and we might be supping with royalty, so simple and true was the kindly courtesy and the good will and understanding.

The gate, which at once kept the pigs out and led to the well had as a hinge an old shoe, nailed on so that it bent at the instep. The well-bucket pulled up on a windlass with a chain.

There was a little Becky Baha; and presently she stooped down, drew from the interior of a quaint, innocent-looking box, eight squawking, fluttering hens, and tied them together with pieces of white cloth. Throwing the white strips of cloth over each shoulder, she started off, swaying with hens, heads turned downwards, a marvel of color, with her bright gown and brilliant burden, stepping down the trail in her bare feet.

A NURSE AND A FIDDLER

The sitting-room of the Medical Settlement [at Big Laurel] is very lovely in detail, with beautiful bunches of roses around in vases. Miss [Harriet] Butler is the head and is the one who makes it so pretty. The house is up among the trees, and down below can be seen the broad creek of the Settlement, with its countless stepping-stones. Nit now are parallel bars Robin has put up, so that even when boisterously drunk the mountain boys cannot break them.

The woman-doctor there has many adventures. The other night Robin reported that she took off to a lonely cabin where she had to perform a major operation. She got water from the well, built a fire in the fireplace filled the kettle and hung it on the crane, put her instruments in it together with an old pair of overalls — all she could find cloth to use — and when these things were ready, performed her work. Robin goes out at night to catch her horse for her sometimes at two or three in the morning.

Percy took a lesson of Uncle John Fiddler the other day and tried to learn to play the tune of “Napoleon Crossing the Rockies.”

A few dahlias and hollyhocks grow by the fence and you enter his place by lifting the wooden bar that opens the age, going through the potato crop. then comes another gate and here you lift off a wire and go into a diminutive yard surrounded by paling. The ground is bare and littered with shavings, and on one side a few rocks with a washtub full of dirty clothes simmering over a smoky fire.

The chickens — an old hen with just hatched brood, and young, gaunt, aggressive broilers — scratch around and jump in and out over the high doorstep of the cabin. Around are old pans and kettles to stick the hens under at night so that the rats won’t get at them. Aunt Louise is very …

p. 291

…feeble —she broke both her arms and had measles last winter — and Uncle John’s hands shake ‘so that he is almost useless, the hens are often entombed in their respective kettles for days at a time. Food is passed into them through the cracks and holes of these discarded vessels of usefulness.

Aunt Loise [sic] wears an old claret-colored dress with white china buttons a red and white bandana kerchief over her head, a necklace of cloudy-white and dark amber-colored beads, heavy brogans, brown knitted stockings, blue jean overalls and shirt, and an ancient felt hat.

HIckory-split chairs, patched up with old wire, are brought out. As we sit down, I wrap my skirts tight around me to keep out the wandering flea. You have to pay the penalty for such a visit by enduring and bringing home a goodly crop of them.

TO HURRICANE GAP

August 9, 1921

Percy and I, accompanied by Ray Holcomb, a mountain boy, have just returned from a grand trip to Line Fork and Hurricane Gap. We started off Saturday afternoon, after attending the election — arriving stiff and sore hardly able to get off our “nags.” Mine was a white mule whose ears wobbled every step he took; Percy’s was a rawboned, stiff-eared mule, short of breath on steep places. Our saddles were hard and made our legs ache. I held on to the pommel of mine in front when I went downhill. The pommel was a piece of wood, whittled out round and nailed on.

The trail for a long way goes through woods of strong-growing laurel, rhododendron, and tall, vigorous trees — a trail so narrow at times that you break the foliage on both sides and have to stoop under the branches. Then we go up a steep ascent and next, seemingly for ages, along the rocky bed of a brook, watching the steps of the mule as it splashes in the water and slips on the stones. It was quite dark going over with rain impending, which made the woods gloomy and somber, and the brook dark. As the sum brightened, we rounded a turn suddenly onto a most beautiful mountain valley.

Here the stream became broad and rock-strewn and glittered like multitudinous mirrors in the sun; again it would have smooth quiet stretches where it reflected pastorally the rural freshness and on each side were broad, rolling pasture -hills reaching to the mountain walls. There were fields of corn and sweet potatoes, gray nestling cottages with their touches of bright-colored flowers, geese n the green — glittering like the stream, only pure silver in the wind and sun — silver in the wind and sun — silver-leafed poplars that quivered dazzlingly, while ‘way on in the distance across the valley, soft with a blue haze, stretched the divine, Hurricane Gap. All is as lovely a dwelling place as beauty owns.

Now we pass a cabin and Ray Holcomb says, “John Milton lives here!” Shades of that “last infirmity of noble minds” — a log cabin in the wilderness! And suddenly John Milton, Jr., appears in the door. “Paradise Regained,” indeed; for this scion of the race appears as in Eden in Adam’s garb — a stark-naked youngster of about three clasping a round ruddy apple to his rounded little tummy!

Next come the homes of the Cornets [local. Cornett] and Fields. “A plague on both your houses” would pass current here, for the feud is strong and vigorous between them; and John Milton himself has just been “rocked” by his neighbor, Bunyan, and his head badly broken.

As we pass the Cornet’s cabin, pistol shots echo in the valley. The Cornets are shooting at a mark to keep their hands in. They are a very active clan, the Cornets. One of them shot his brother the other day and is now in the “pen” awaiting sentence. The one who was shot, Bunyan Cornet, again suggests by name the cultural inheritance of this valley’s “generation.” We wind past a little store which marks yet another “hardness,” for an uncle has just peppered his nephew three times with shot.

So we reached the Line Fork Settlement, a little alpine hostelry on a steep incline over the road, and Miss Dennis comes out to welcome us, a worker in France during the war and now a courageous pioneer in these mountains. We got off our mules to totter into the charming little home: first a tiny kitchen with refectory table and bench, cook-stove and square table (every leg a cupboard) then two bedrooms, comfortable, ….

p. 292

… clean and homelike. How good it seemed to have rest and refreshment there after our arduous toil!

After supper and a talk, we arranged to go next day to a “funeralizing,” and make an early start. On the way that morning, we came to a cabin where a crowd had collected and, in the midst of it, a man holding onto the paling [fence type]. With his head swathed in white bandages, you couldn’t have told what sort of a man he was, as he was totally effaced above the shoulders. Here was the hero of the day — the “rocked” John Milton’s, but a “mute inglorious ” one!

THE “FUNERALIZING”

From all the cabins were now coming the inhabitants, and wending along with us, the women sitting side-wise on meal sacks behind their husbands who occupied the saddles. The gathering grew as we started up the last steep incline, we were part of a Chaucerian multitude, laughing, joking, bobbing, and jostling along; walking or stirrup-to-stirrup on varicolored mules; young people and old, and among them, the jolliest of the all, ruddy-faced, white-haired and mustachioed, was old Preacher Charlie Blair.

We tied our mules with the others in the creek, got over an eight-rail fence as all did, and went up past a house to the little cemetery above it. Here was the family burying ground. The older graves are mounds of dirt, with old, worn, lichen-covered slate stones very small and low, roughly rounded at the top. There was one little new mound, with a tiny marble slab on it, such as could be carried across the mountain on horseback. The mounds were covered with flowers. In the middle was a larger grave, covered with a newly painted, roofed slat house, white and green, about four feet high, built to decorate and cover a newly-made grave, and to keep out the hogs and other animals.

Here, gathered around the preacher, Boone Cornet, were a concourse of people weeping loudly, as he exhorted them to remember their sins and the dead, departed sister and mother, who had “out-stripped them in the lane of life.” He chanted his exhortation with much nasal inflection, reaching to a high shriek, both hands over his ears. Bowing his body almost to the ground, he would begin over again. Then he would day the first line of a song and the people would improviser the next; another and another — melancholy, lugubrious lines. After which he would go around shaking everybody’s hand and they cried and sobbed.

In the midst of this, the heavens themselves began a-weeping and we were told to go up the creek about a mile to the home of the departed Betsy. So we all started off in a mule-back cavalcade some walking, through the pouring rain till “way up yander” we came to two little cottages. On the front of one had been built a porch for the occasion, and to one side, new boards were arranged as benches for the people to sit on. Here, as the shower cleared, we took our places with the rest.

OLD CHARLIE’S “PREACHMENT”

The old preacher, Charlie Blair, now arose and took off his coat. He had on a black shirt, suspenders, and dirty trousers — on which he continually wiped his hands after blowing his nose (mountain fashion). IN singsong, with hardly a stop for breath, he began:

“Now, breather, I don’t know how long I shall speak, and I may never see you again. I’m gittin’ old, but no matter how long I speak, I’ve as fur to go as you have, and the rheumatiz; but when I git religion and git a feeling’ of it, I fergit all about that. Oh, “brethren!” What a great thing it is!” (The “Oh!” was a high shriek, the “brethren” coming down the scale to a monotone.)

“Now but this is true that we’ll all come to heaven, thank Jesus, but we’ll never git that jest by doin’ good works will we ow, Brother Boone? No! That’s not the way St Paul said. Jesus He said ‘In my Father’s house is many mansions, and I go to prepare a place for you,; and if He said that there’s shore a mansion that for everyone of us that repents, and for him that doesn’t, th’ isn’t.

“Yea, brethren, the sweet promise of the Lord (hum) shall carry us over the cold stream of Jordan (hum), and we shall be took to Abraham his bosom! Oh!!!, brethren, don’t we want to go? And He don’t want His people all daubed up with intemperate mortar, nuther (hum.”

Old Charlie waves his hands back and forth; prances, on his two feet; turns his back to the audience to get confirmation from the chief mourner, the husband of Betsy who sits beside him. Then he backs toward the edge of the porch hands surging back and forth; and over goes a small child, flying through the air, struck into space by a vehement blow from the swinging hands. The child rolls over and over on the ground, but Old Charlie goes right on with a “Bless ye, my child! We’re all goin’ to heaven!”; prancing to the other edge of the porch in his powerful flow of eloquence, and takinin Martha Lewis’s vocabulary, the g a dripping drink. (He has the palsy and his hands shake, the water pouring down his shirt front.) He drinks from the general bucket and dipper, blows his nose waves his hands aloft to his God, and “hollers” of the Last Trump and the Unready …. of the careless virgins who didn’t have their lamps trimmed …. of the virtues of old Betsy, who by the way, was, in Martha Lewis’s vocabulary, “the meanest woman who ever lived” …. of the despairing children, who, if they ever want to see her again, must repent their sins before it’s too late and come to the Immaculate Lamb.

Then from his chanting he will suddenly come down to his usual tone of voice and tell a joke, addressing someone in the audience and laughing at his own witticism.

The preachers never accept a penny for these services, but farm for their living as other men do, and go around preaching purely for charity (and power) and a Chaucerian love of people, crowds, and gatherings.

Another preacher began, and we left for our mules in the creek mounted them for the long descent of the mountain, and very thankfully reached kind Miss Dennis’s house and a good supper. There, sitting on her little porch in the evening, we listened to the night noises, the owls, the katydids, and innumerable “mournings,” as Robin calls them.

OF WITCHES AND ROMANCE

In the morning, so fresh and mountain, we walked down with Miss Dennis to see old Will and Martha (“Marthy”) Lewis. We passed hogs suckling their shots in the road, jumped across the creek on the rocks, and went up a stony hill and into a little gate — through chickens and turkeys, past the pet black and white dog — to where old Aunt Marthy sat on her porch, stringing beans for dinner. She is slim and sinewy and brown, with bright eyes, straight gray-brown hair, parted in the middle and done up with two combs. She wears an old straw hat, patched with oilcloth from the kitchen table, a brown and yellow and grayish calico dress belted at the waist, and heavy brogan shoes.

Aunt Marthy told us Saxon tales of witches as we helped with the beans. Old Will Lewis joined us and discoursed to Percy about “yarbs” while I went into the kitchen with Martha. There the daughter-in-law was getting dinner of fried salt pork, beans, biscuits, coffee, milk, blackberry pie, and fresh butter. A mark on the doorsill they said, was set by a compass, and “when the sun’s shadder got that, it was always twelve o’clock.” They insisted on our staying to dinner, and we all sat along on the old, scarred, rustic bench.

Later, Percy and I sat out with Aunt Marthy on an old bee-gum stump and she talked of her step grand-mother who, so she said, was a witch and turned herself into a “yeller” cat, and of old Black Lara a “slick” Negress, who turned herself into a black cat, and they went around the country together doing “devilments.” Her “step-granny,” the witch — Old Granny Big Poll — had to leave the country and went to Missouri. “They stuck wheel-spinnels into her and burnt her rump so she couldn’t sit down, and they’d like t’ killt her if

p. 302

she hadn’t a-quit the country.”

This led on to the story of her own grandmother. Her grandfather was riding through Virginia when he met a barefoot girl on the trail searching for her cows. He stopped and talked to her, and at his request, she got up on the saddle behind him. They rode ten days till he reached his home and then they were married. He was eighteen and she thirteen, and all she had on was the dress to her back. She never saw her people again or heard from them; just jumped up behind and off they went and, my goodness, you can see it now in Aunt Marthy’s eye: the bold adventure and the light heart, merry ring of gallant metal and a swift jump at every stile — and life with a zest.

We left lingeringly and wandered back to Miss Dennis’s for the night. Starting homeward in the morning, the sky clear blue, the clematis flowering — by evening we had reached our dear “Old Log,” at Pine Mountain.

Uncle John Fiddler and Aunt Louize. [cobb_alice_041.jpg]

UNCLE JOHN FIDDLER

For us, the guardian spirit of Pine Mountain is Uncle John Fiddler,* and we shall ever recall the morning of our earliest encounter with him. That was the Fourth of July at the outdoor assembly place here when we first met many of our mountain neighbors. There were speakers, and Percy read aloud his one-act play, “Gettysburg,” first calling old Uncle John to come up on the platform. There her sat down on the floor and, turning up his old, time-worn face, listened entranced.

Percy read beautifully. The force of his grace of mind and spirit, his heavenly beaming smile, his enthusiasm and spontaneous response to those about him were beyond all I can possibly write in my meager power.

Uncle John says to him, “You are a poet,” and he to Uncle John, “You are a poet.”

Later, we sat on a log, we three, and Uncle John Fiddler spoke of heaven and heavenly things; and out of his distorted, bleared old eyes there dawned a beauty of a soul — a direct message from the oversoul of men, gotten in long journeys up and down the earth, consorting and discoursing with men and angels and savages nature and primal truths in the primal truths in the primeval forests! The Bible he has studied well; seven times has he read it through and it tempers all his speech. A marvelously beautiful denizen of an ancient world, old and yet forever new, his spirit symbolizes these wilds.

Vast, I see him in imagination, standing there above the hills, fiddle in hand the light eternal in his eyes; music, love life-everlasting flowing gently, mystically from his form, with the old neckerchief, and through all his multitudinous wealth of pictured speech.

*Uncle John Fiddler (Lewis), of Greasy Creek, Pine Mountain, then over eighty. His characteristics of soul and of folk-speech are reflected in the character, Uncle Lark Fiddler, in two of Percy MacKaye’s plays, “Napoleon Crossing the Rockies,” and “This Fine Pretty World.”

This was the first of three articles — a second by Mrs. MacKaye; the third, an unpublished sketch by Percy MacKaye of the “Oldest Man in the World.” [John Shell]

[The following two poems accompanied the article on page 292.

DEATH AND THE WILD DOVE

by P.M. for M.M.

How very near death is to love!

He lurks beside — behind — before.

He warbles deep with the wild dove:

No more! — no more! — No more!

He blushes where quick rapture starts;

He makes his vow in mingled breath,

His requiem in chiming hearts —

So near to love is death!

Yet oh, how dear to love death is!

For love alone divinely knows

How all is hers in being his,

Her radiance — his rose.

So near and dear death is to love

‘Tis they who through the moaned No more

Chant with that will, immortal dove —

Adore!–adore!–adore!

__________

SONG OF THE DAWN BIRD

by M.M.M. for P.M

Softly sings the sweet bird

Softly murmurs the sweet brook,

Softly the golden glory stretches

Gently up the healed sky:

Sing, for it’s almost morning,

Sin for it’s now your time;

Sing, for the grace of heaven,

Sing, for thou art mine.

Happy the bird at the dawning,

Happy the bird at rest;

Happy the burden of loving

Happy to be so Blest:

Sing, sing, sing, for the light is breaking

Over the hills and sky;

Sing, for your love is coming,

Coming — and he is nigh!

GALLERY: PERCY MacKAYE and MARION MacKAYE VISITORS 1921 “God, Humanity and the Mountains”

- 001 mackaye_god_humanity_mtns_SG-1946_001

- 002 mackaye_god_humanity_mtns_SG-1946_002

- 003 mackaye_god_humanity_mtns_SG-1946_003

- 004 mackaye_god_humanity_mtns_SG-1946_004

- 005 mackaye_god_humanity_mtns_SG-1946_005

- 006 mackaye_god_humanity_mtns_SG-1946_006

- 007 mackaye_god_humanity_mtns_SG-1946_007

- 008 mackaye_god_humanity_mtns_SG-1946_008

See:

PERCY MACKAYE Visitor 1921 – Biography

PERCY MACKAYE VISITOR Appalachian Play Reviews – Reviews of plays by MacKaye in various publications, 1920s; also, a review of a play by Hatcher Hughes.

PERCY MACKAYE VISITOR and His Appalachian Creative Work [in progress]

PERCY MACKAYE VISITOR “Untamed America” – Article by MacKaye, published 1924

RELIGION A Mountain Funeralizing

CELIA CATHCART A Funeralizing on Robber’s Creek

FIDDLER JOHN LEWIS Community – Biography

RUTH DENNIS Staff – Biography