Pine Mountain Settlement School

Series 04: ADMINISTRATION

Ethel de Long Zande

Co-director &Co-founder

“The Pine Mountain School

A Sketch From the Kentucky Mountains”

1915/1917 Talk and Publication

TAGS: Ethel de Long Zande publication and talk, “The Pine Mountain School A Sketch from the Kentucky Mountains, colloquialisms, fundraising talks, The Outlook 1917, ballads, William Creech, mountain culture

ETHEL DE LONG ZANDE

Pine Mountain School

A Sketch from the Kentucky Mountains

Talk by Ethel de Long presented at the 43rd Annual Conference of Charities,

June 7, 1915, and published in Outlook, Feb. 21, 1917, pp. 318-20. Reprint and notes available in the Pine Mountain Settlement School Collections, Pine Mountain, KY

Ethel de Long Zande, one of the co-founders of Pine Mountain Settlement School, was frequently called on to give talks about the School. This talk most likely was given in the first years of the School and calls forward many of the colloquialisms that were found to be popular with audiences of the day. It also provides a good view of de Long’s own aspirations for the new school and her understanding of the culture she found in the community.

Tellingly, she describes the community as “… a people with their faces set toward the morning.…” It is an image that all who know the valley of the Pine Mountain, know that it is oriented roughly along an East to West axis. In the morning the sun is slow to come over the close mountains, but it never stops being a wondrous event when the first rays of light break through. In many ways it is an experience that goes with each sunny morning and it never ceases to delight and hold the promise of good days ahead. The image of turning to face the early morning sun has never lost its power to describe the hope that many workers found in the Kentucky mountains and one that they continue to hold dear.

TRANSCRIPTION

THE PINE MOUNTAIN SCHOOL

A SKETCH FROM THE KENTUCKY MOUNTAINS

BY ETHEL DE LONG

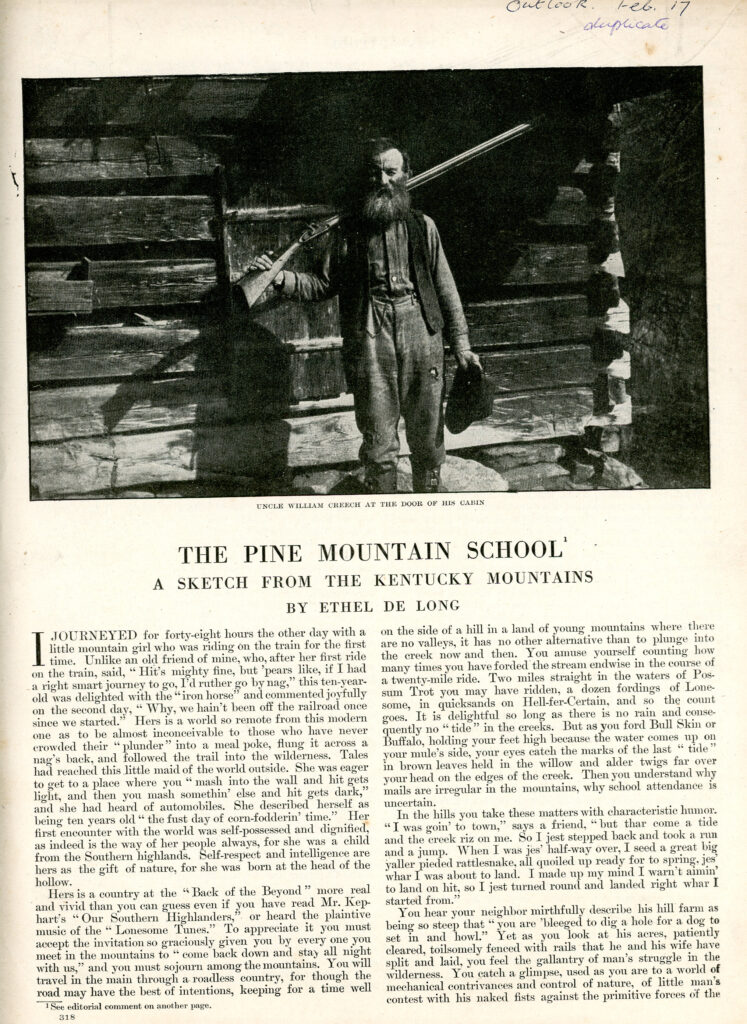

“Uncle William Creech.” [kingman_076a, jpg]

I JOURNEYED for forty-eight hours the other day with a little mountain girl who was riding on the train for the first time. Unlike an old friend of mine, who, after her first ride on the train, said, “hit’s mighty fine, but ‘pears like, if I had a right smart journey to go, I’d ruther go by nag,” this ten-year-old was delighted with the “iron horse” and commented joyfully on the second day, “ ‘Why, we hain’t been off the railroad once since we started.” Hers is a world so remote from this modern one as to be almost inconceivable to those who have never crowded their “plunder” into a meal poke, flung it across a nag’s back, and followed the trail into the wilderness. Tales had reached this little maid of the world outside. She was eager to get to a place where you “mash into the wall and hit gets light, and then you mash somethin’ else and hit gets dark,” and she had heard of automobiles. She described herself as being ten years old “the fust day of corn-fodderin’ time.” Her first encounter with the world was self-possessed and dignified, as indeed is the way of her people always, for she was a child from the Southern highlands. Self-respect and intelligence are hers as the gift of nature, for she was born at the head of the hollow.

Hers is a country at the “Back of the Beyond” more real and vivid than you can guess even if you have read Mr. Kephart’s “ Our Southern Highlanders,” or heard the plaintive music of the “Lonesome Tunes.” To appreciate it you first accept the invitation so graciously given you by everyone you meet in the mountains to “come back down and stay all night with us,” and you must sojourn among the mountains. You will travel in the main through a roadless country, for though the road may have the best of Intentions, keeping for a time well on the side of the hill….

Cabin and hillside. Series VII-52 Children & Classes. [elem_005.jpg]

On the side of a hill in a land of young mountains where there are no valleys, it has no other alternative than to plunge into the creek now and then. You amuse yourself counting how many times you have forded the stream endwise in the course of a twenty-mile ride. Two miles straight in the waters of Possum Trot you may have ridden, a dozen fordings of Lonesome, in quicksands on Hell-fer-Certain, and so the count goes. It is delightful so long as there is no rain and consequently no “tide” in the creeks. But as you ford Bull Skin or Buffalo, holding your feet high because the water comes up on your mule’s side, your eyes catch the marks of the last “tide” in brown leaves held in the willow and alder twigs far over your head on the edges of the creek. Then you understand why mails are irregular in the mountains, why school attendance is uncertain.

In the hills you take these matters with characteristic humor. “I was goin’ to town,” says a friend, “but thar come a tide and the creek riz on me. So I jest stepped back and took a run and a jump. When I was jes’ half-way over, I seed a great big yaller pieded rattlesnake, all coiled up ready for to spring, jes’ whar I was about to land. I made up my mind I warn’t aimin’ to land on hit, so I jest turned round and landed right whar I started from.”

PMSS staff and others on two mile walk down Greasy Creek for dinner at Aunt Judy’s following church. _II_086b

You hear your neighbor mirthfully describe his hill farm as bein’ so steep that “you are ‘bliged to dig a hole for a dog to set in and howl.” Yet as you look at his acres, patiently cleared, toilsomely fenced with rails that he and his wife have split and laid, you feel the gallantry of man’s struggle in the wilderness. You catch a glimpse, used as you are to a world of mechanical contrivances and control of nature, of little man’s contest with his naked fists against the primitive force of the world. You feel profound respect for the pioneer who could start out with his wife and his children, all his worldly possessions on a nag’s back, into a wild country which he could subdue only with his hands, aided by a flintlock gun and an ax.

Yet this country of the Cumberlands was rich to the eyes of the pioneer who came into it after Daniel Boone had found out a wilderness road, “follerin’ the game,” and who then “holp”

to subdue the wilderness. Even less than a generation ago it abounded in fish and game. The pea vine grew over the hills, making the best of grazing for stock. There were sugar trees

to give you “sweetenin’,” and tulip blossoms enough so that the bees could fill the old-fashioned bee-gum with a wealth of honey for you. Even to-day, when the bees and the bears are gone and a mess of fish is a treat, the trappers find mink and red fox, coon and ‘possum, and the industrious can still dig for themselves an honest penny when they go “sanging” in the woods; for whereas fifty years ago ginseng brought only twenty-five cents a pound, to-day it sells for about five dollars and sometimes goes as high as eight. But if the good old days are gone for the pioneer, they are only beginning for the capitalist. Fortunes have already been made in timber in the Kentucky mountains, and the coal-fields just being opened are said to be the richest in the world. There are fortunes, indeed, in the mountains for men who have bought fifty thousand acres of original forest for fifty cents an acre; who have purchased poplar trees, averaging from two thousand to ten thousand feet of lumber, at two dollars a tree; and have bought in trade six hundred acres of land for a little gray nag and a squirrel-shooting rifle. But, even though in his first encounter with the commercial world the mountain man was not shrewd enough to hold his own, the greatest wealth of the mountains is the people themselves. It is already becoming trite to speak of the “purest Americans in America,” so well known is the fact that the mountain people are practically a homogeneous race, their fore-parents who came from way yon side of the briny deep having been mostly English, Scotch, and Irish in race. If you want proof of it, stop your nag in midstream and listen to the girl hoeing corn at the top of the mountain, and singing to keep herself company the song the grandmother taught her sitting by the fire on winter evenings:

“I looked over yander and I seen paw coming,

He’s walked for many a long mile.

Say, paw, say, paw, have you brung me any gold,

Any gold for today my fine?

No, sir, no, sir, we brung you no gold,

No gold for to pay your fine,

For I’ve just come to see you hanged,

Hang on the gallows line.

Hangman, hangman, slack up your rope,

“1 looked over yander and I. seen paw coming,

He’d walked for many a long mile.

Say, paw, say, paw, have you brung me any gold,

Any gold for to pay my fine?

No, sir, no, sir, we brung you no gold,

No gold for to pay your due,

For I’ve just come to see you hanged,

Hang on the gallows line.

Hangman, hangman, slack up your rope,

Slack it for a while!

I looked over yonder and I seen maw coming,

She’s walked for many a long mile.”

It is the original ballad of the” Briary Bush,” and goes back to the time when men were hanged for debt. You can hunt it out in Professor Child’s English and Scottish Ballads but we of

the mountains do not consider it as a quaint bit of literature to be unearthed by scholars. It is just one of our “song ballets.” And though some strict church members in the mountains may

count it and such a love song as “Barbara Allen” or “Jackaro” as “devil’s ditties,”* they have been saved through generations as the heritage from home of the mountain people. And then listen to the everyday speech. An old woman who can shear twenty-eight sheep in a day, and knows how to scour the wool, to spin, dye, and weave it into linsey-woolsey or into a coverlet whose pattern may be called “King’s Plower” or “Queen’s Patch” or “Lonely Heart,” tells you, “No, you cain’t never toll sheep off their usin’ grounds of an evenin’,” and you remember Shakespeare’s double negatives and Spenser’s “Where never foot did use” in “The Faerie Queene,” though to-day we have forgotten that old meaning, “ to frequent,” of the word “use.” Has somebody been “acting anticky,” did not Hamlet put an “antic disposition on”? When you have been invited to a frolic, remember that Lady Mary Wortley Montagu did not go to “at homes,” or the dansants either, but records herself as invited to “frolicks.” Very probably she too would have complained of some mischievous little boy that he had been “pranking with her things,” and certainly she would have understood the apologetic mother who snatched her baby from the floor, saying, “God love my baby! Hit’s motley faced. I hain’t had no time to clean hit to-day.”

If you would learn the art of racy, beautiful speech, come to the mountains where speech still blossoms freely. Where a woman speaks of her youth as “the rise of her bloom,” and the preacher prays for the old as “those whose heads are a-blooming for the grave.” Where someone who has outstayed her visit, singing to the accompaniment of the dulcimer, cries at

leave-taking, as she remembers the night duties awaiting her at the end of a seven-mile walk, “Lord, I won’t never be satisfied away from you again no more in this world!“ Where a child eager to see you writes that she would like to “hold your lily white hand,” and another one, wanting an answer to her letter speedily, puts on the corner of the envelope, “Go in haste.”

It is easy to see the defects and limitations of the mountains—their need of roads that can bring greater economic opportunities; of good schools that can prepare them for the world that is not merely knocking at their doors but snatching their homes away from them, thrusting them into a competition for which three generations of life in the woods has unfitted them; of preventive medical work which shall free them from the incubus of hookworm and eradicate trachoma; of effective co-operation for a people whose life has made them the sturdiest of individualists. These defects have been a matter of talk for so many years that to-day there is need to remember that these are a people with their faces set toward the morning; as a group, the three million of them living in the remote Appalachians, undeveloped wealth for America. Meeting their keenness of mind, one discovers that reading and writing are something of a shibboleth, not a true touchstone of intelligence; that poise and dignity of behavior are qualities of the heart, not of environment; that the bringing up of children to obedience and beautiful manners may be successfully done by the mother of a dozen whose day is full of tasks and who has had no opportunities.

Rhoda Creech Wilder’s Family: Kermit 8, Brit 10, Sallie 12 (holding ?), Mary 1, Margaret 3, Cindy 6, Polly 4. [Vl_37_1195a.jpg]

If you have felt it America’s duty to decrease the percentage of illiteracy in the Southern mountains rather than her privilege to stretch out the hand of opportunity, if you have grudgingly admitted that in self-interest we ought to provide better educational facilities and insist on their being used, listen to the mother who said, when she was asked if she made her children go to school, “Lord! they hain’t to make, they cry to go.” The biggest thing about people on the lonesome creeks hidden away in the folds of the mountains is that they crave a chance. As one father put it: “I want my little fellers raised toward humanity.” There are men in the mountains who for years have dreamed wistfully of a chance for their people, though they could never see how it could come. Few of us have done as much original thinking as Mr. William Creech, who a few years ago gave all he had to establish a settlement school in his neighborhood. For forty years he had wanted a school that would not only teach book learning, but would “larn folks to do things with their hands,” because “hit’s better for folkses characters to larn them to do things with their hands ;“ and who wrote:

My idea was that if we could get a good school here and get the children interested it would help moralize the country. If we can bring our children to see the error of the liquor we can squash it.

Some places hereabouts are so lost from knowledge that the young uns have never been taught the knowledge of reading and writing and don’t know the country they were borned in or what State or County they was borned. We need a whole lot of teaching how to work on the farm and how to make their farms pay, also teachin’ them how to take care of their timber and stuff they’re wasting.

If the school has as its ideal not only the fitting of boys and girls for life in the mountains, but of large community service which shall include preventive medical work, and the building of a good road across the mountains and in all the hundred and fifty miles between the ends of Pine Mountain, which runs from “Praise the Lord” to “Hell’s Point,” there is not one good road across it, it can never outstrip Uncle William’s visions. He says:

We want to teach them books and agriculture and machinery and all kinds of labor and to help them to live up as good American citizens. We are trying to teach them up so they can be a help to the poor and to the generation unborn. . .

I don’t look after wealth for them. I look after the prosperity of our Nation. The question of this world is naught. We are born into it naked and we go out naked. The savin’ of the soul is what we should seek. I want all young uns taught to serve the livin’ God. Of course they won’t all do that, but they can have good and evil laid before them and they can choose which they will. I have heart and cravin’ that our people may grow better. I have deeded my land to the Pine Mountain Settlement School to be used for school purposes as long as the Constitution of the United States stands. Hopin’ it may make a bright and intelligent people after I’m dead and gone.

When we drew up the deed which transferred all Uncle William’s land to the Pine Mountain School, he insisted that I put somewhere in the lien those very words, “to be used for school purposes as long as the Constitution of the United States stands.” So I wrote it in the “To have and to hold “ clause, and then, fearing that he and I might not have made the instrument as legally sound as it should be, I sent it off to be inspected by a Blue-Grass lawyer. When it came back, vouched for as to its legal soundness, Uncle William, full of joy that his words would stand, exclaimed just as he was about to sign it: “ That’s fixed hit. ‘Thar’s bound to be a school here now, ‘less some furrin Power comes and wipes this country up.”

**********

**”Devil’s ditties” finds an expanded chapter in Lucy Furman’s book, The Quare Women [Boston: The Atlantic Monthly Press, 1923], a novel that obliquely describes life in and around Hindman Settlement School in Knott County, Kentucky, where Ethel de Long and Katherine Pettit first taught. In the novel, an elder in the community feels compelled to go up the mountain to a secluded place where she can sing the songs passed down through generations, but that are considered pagan and “sinful” in their story. [hhw]

See Also:

ETHEL DE LONG ZANDE Director – Biography

Return To:

ETHEL DE LONG ZANDE Writing and Publications Guide